While cyber forensics is clearly a very technical process, technical prowess alone is not enough. Throughout this book, we will spend a great deal of time on specific technical processes, procedures, and techniques. However, the ethics of forensics is just as important as the technical process. In fact, one can do everything technically correct, but an ethical issue can render evidence inadmissible in court. And in some cases, a breach of ethics could, in fact, end a cyber forensics analyst’s career. So the material in this chapter is quite critical, both for the Certified Cyber Forensics Professional certification test and for your career itself.

Chain of Custody

The concept of chain of custody is one of the cornerstones of forensic science, whether that is cyber forensics or some other forensic discipline. Chain of custody refers to detailed documentation showing the status of evidence at every point in time from the moment of seizure to the moment the evidence is presented in court. Any break in that chain of custody will likely render that evidence inadmissible at trial.

TIP Failure to maintain the chain of custody is an egregious error. I am certain you have seen police dramas on television wherein some key evidence was excluded due to some gap in the chain of custody. This part of crime dramas is accurate. You must be able to completely document the chain of custody from the point of seizure to the point of trial.

According to the Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence Model Standard Operation Procedures for Computer Forensics:

The chain of custody must include a description of the evidence and a documented history of each evidence transfer.1

This definition is worth further examination. Notice it states “history of each evidence transfer.” Any time that evidence is transferred from one location to another, or from one person to another, that transfer must be documented. The first transfer is the seizure of evidence when the evidence is transferred to the investigator. Between that point in time and any trial, there may be any number of transfers.

The first transfer occurs when the evidence is initially seized. At that point, a complete documentation of the scene, the personnel involved, date, and time should be performed. Then, each time the evidence is moved to any new location, examined, or a different person accesses it, this all should be documented. In law enforcement, this is accomplished with an evidence tag. An example of an evidence tag is shown in Figure 2-1. Obviously, specific law enforcement agencies will have some slight differences in how they format their evidence tag (note this tag has the police department name redacted).

Figure 2-1 Evidence tag

Normally, evidence is kept in a secure location, one with a lock and controlled access. Anytime the evidence is accessed, that access (including who, date, time, and what was done) is documented. The final transfer occurs when the evidence is taken to court.

NOTE It is important to keep in mind that a few jurisdictions have passed laws requiring that in order to extract the evidence, the investigator must be either a law enforcement officer or a licensed private investigator. This is a controversial law, given that normally, private investigator training and licensing do not include computer forensics training. You should check with specifics in your state, but in general, this does not preclude a computer forensics expert from analyzing the evidence; however, someone else might need to seize it. This immediately brings up the issue of chain of custody. The person seizing the evidence is not the examiner, and it is imperative that chain of custody be preserved.

Securing the Scene

In non-computer crimes, like burglary or even homicide, the crime scene is blocked off by police tape. This is to prevent people from contaminating the crime scene and to give the forensic team the opportunity to collect evidence. Such obvious physical barriers may also be present in some computer crime investigations, but not all. In the case of a computer crime scene, you must secure the computer, network, or target area of the attack. Usually, that will mean preventing access to the system. That will include disconnecting from the network and preventing people from accessing the system.

While a computer crime may seem quite different from a non-computer crime, many of the investigation principles are the same. For example, in a non-computer crime scene, you remove everyone from the scene who does not absolutely need to be there to conduct the investigation. The same principle applies to a computer crime investigation. The only people who should access the system(s) that are the subject of the investigation are those people with an actual need to perform some part of the investigation.

No one who does not absolutely need access to the evidence should have it. Hard drives should be locked in a safe or secure cabinet. Analysis should be done in a room with limited access.

Documentation

If you have never worked in any investigative capacity, the level of documentation may seem onerous to you. But the rule is simple: Document everything It is really not possible to overdocument. It is likely that some cases will depend more on certain aspects of the documentation than others; however, you won’t know what documentation is really important until the case is done. So err on the side of caution and document everything.

What do we really mean when we say document everything? Well, the documentation process begins at the crime scene itself, when you first encounter the crime scene. When you first discover a computer crime, you must document exactly what events occurred. Who was present and what where they doing? What devices were attached to the computer, and what connections did they have over the network/Internet? What hardware was being used and what operating system? All of these questions must be answered and must be documented.

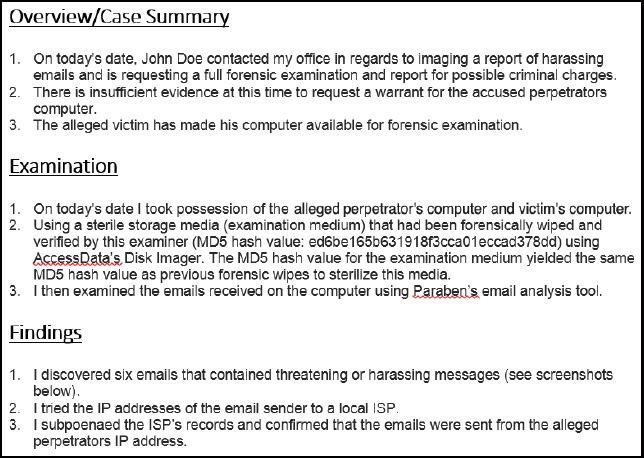

Then when you begin your actual forensic investigation, you must document every step. Even before you begin your actual analysis, you will document the crime scene and the process of acquiring the evidence. You should also document how the evidence is transported to your forensic lab. From there, you continue documenting every step you take, starting with documenting the process you use to make a forensic copy. Then document every tool you use, every test you perform. You must be able to show in your documentation everything that was done. You can see a brief sample of a report in Figure 2-2.

Figure 2-2 Sample report

You should note that this sample seen in Figure 2-2 is intentionally brief so that it fits well in an image. As mentioned, there really is no such thing as overdocumenting. More detail is always better. The SANS institute also gives some guidance on documenting a cyber forensic investigation at http://computer-forensics.sans.org/blog/2010/08/25/intro-report-writing-digital-forensics/. According to the Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence (SWDGE),2 a report should include the following:

The report is to provide the reader with all the relevant information in a clear and concise manner using standardized terminology. The examiner is responsible for reporting the results of the examination.

Reports issued by the examiner must address the requestor’s needs and contain the Identity of the reporting organization.

• Case identifier or submission number.

• Identity of the submitter.

• Date of receipt.

• Date of report.

• Descriptive list of items submitted for examination.

• Identity and signature of the examiner.

• Description of examination.

• Results/conclusions/derived items.

When documenting your analysis, the process should be documented with a level of detail that would allow any competent forensic examiner to take your documentation and be able to replicate your entire testing process. So it is not enough to simply say, for example, that you used AccessData to image a drive. Rather, you must give a step-by-step tutorial as to how you did the imaging.

TIP It is also a good idea to use photographic and video documentation. Photographic documentation is usually done at the crime scene. The entire scene is photographed from multiple angles. Videotaping the crime scene is also possible, as well as using videotape to document the examination procedures.

Authority and Objectives

It is important that a forensic examiner be certain that he or she has the authority to investigate given evidence. Normally, these decisions will be made by lead investigators (law enforcement) or attorneys, but you do need to be aware of the issues.

One of the major issues is jurisdiction. In criminal cases, one of the first steps to decide is who has jurisdiction. Is this a federal, state, or local case? Or is it an intelligence matter and not a criminal one? In civil cases, the rules for that specific court (federal or state) must be adhered to.

Once you have established jurisdiction, the forensic examiner should at least be aware of whether or not there exists the authority to seize and examine the evidence. Was there a warrant or did the owner give consent? Was consent given in writing? If there was a warrant, did it specify this certain piece of equipment? If it did not, there should be some documentation/explanation as to why it was seized.

After you have determined that you have the authority to examine the evidence, you should establish some objectives. Forensic analysis is not a fishing expedition, hoping to find something juicy. You should have specific goals for your analysis.

Examination

Clearly, the examination is the most critical part of the forensic process. Of course, the seizing of evidence must be done according to accepted protocols. And the documentation of the procedures used is very important. However, all of those activities are in support of the actual examination.

According to the SWGDE Model Standard Operation Procedures for Computer Forensics,3 there are four steps to an examination:

• Visual Inspection The purpose of this inspection is just to verify the type of evidence, its condition, and relevant information to conduct the examination. This is often done in the initial evidence seizure. For example, if a computer is being seized, you would want to document if the machine is running, its condition, and the general environment.

• Forensic Duplication This is the process of duplicating the media before examination. It is always preferred to work with a forensic copy and not the original.

• Media Examination This is the actual forensic testing of the application, which will take up a great deal of the rest of this book. By media, we mean hard drive, RAM, SIM card—any item that can contain digital data.

• Evidence Return Exhibit(s) are returned to the appropriate location, usually some locked or secured facility.

These steps cover the overall process. If any of these steps are omitted or performed incorrectly, the integrity of the investigation could be called into question.

EXAM TIP The CCFP exam relies heavily on the SWGDE standards and documents. Anywhere in this book you see SWGDE cited, you should give that particular attention. It is also recommended that you visit their website and review any documents prior to taking the CCFP exam: www.swgde.org.

Code of Ethics

While there are legal requirements regarding forensic investigations, there are also ethical requirements, and these are just as important. As a forensic investigator, you need to keep two facts in mind. The first is that there are significant consequences resulting from your work. Whether you are working on a criminal case, a civil case, or simply doing administrative investigations, major decisions will be made based on your work. You have a heavy ethical obligation. It is also critical to remember that a part of your professional obligation will be testifying under oath at depositions and at trials. With any such testimony there will be opposing counsel who will be eager to bring up any issue that might impugn your character. Your ethics should be above reproach.

As you will see in this section, there is certainly overlap between ethics and legal requirements, but they are separate topics. One way of thinking about the difference between law and ethics is that ethical guidelines begin where the law ends.

(ISC)2 Ethics

Before we begin an examination of the details of ethical requirements in forensic investigations, it is useful to first examine the (ISC)2 ethical guidelines. Every person taking an (ISC)2 certification test (CISSP, CSSLP, CCFP, etc.) agrees to abide by these ethical guidelines.4 These guidelines are

• Protect society, the common good, necessary public trust and confidence, and the infrastructure.

• Act honorably, honestly, justly, responsibly, and legally.

• Provide diligent and competent service to principals.

• Advance and protect the profession.

Essentially, these ethical guidelines are general principles designed to provide a framework within which to practice the profession of cyber forensics. They are intentionally general, and one could say vague. My own policy is that when in doubt as to what the ethical course of action is, err on the side of caution. Put another way: If you believe something might be unethical but cannot decide, assume that it is unethical and act accordingly. You should note that the ethical guidelines published by the (ISC)2 do not describe specific laws you must follow.

American Academy of Forensic Science Ethics

The American Academy of Forensic Science (AAFS) encompasses the entire breadth of forensics, not just cyber forensics. That includes fire forensics, medical forensics, financial forensics, etc. While the technical details of each type of investigation are quite diverse, the ethical challenges are remarkably similar. But due to the wide range of forensic subdisciplines, most of the AAFS ethical guidelines are necessarily broad. The actual ethical guidelines are listed here:5

a. Every member and affiliate of the Academy shall refrain from exercising professional or personal conduct adverse to the best interests and objectives of the Academy. The objectives stated in the Preamble to these bylaws include: promoting education for and research in the forensic sciences, encouraging the study, improving the practice, elevating the standards and advancing the cause of the forensic sciences.

b. No member or affiliate of the Academy shall materially misrepresent his or her education, training, experience, area of expertise, or membership status within the Academy.

c. No member or affiliate of the Academy shall materially misrepresent data or scientific principles upon which his or her conclusion or professional opinion is based.

d. No member or affiliate of the Academy shall issue public statements that appear to represent the position of the Academy without specific authority first obtained from the Board of Directors.

Item a is a generic admonition to behave in a way that does not embarrass the Academy and in fact improves its reputation. Item d is similar in that it directs members not to speak, or even appear to speak, on behalf of the AAFS.

Items b and c are of most interest to our discussion of ethics. Item b essentially says don’t exaggerate. This is actually wonderful advice, though it may seem unnecessary. You might wonder if any expert would really exaggerate his or her credentials. The unfortunate answer is that yes, some would. In fact, I have personally encountered incidents of this sort of behavior. For example, someone might have a legitimate degree, even a master’s degree, but to enhance his or her resume, they might get a doctorate degree from an unaccredited degree mill. Just as disconcerting is passing of self-published e-books as published works. When one publishes nonfiction, the publisher puts the book through a thorough vetting process, similar to peer review. Multiple editors, including a technical editor, review the book. In the case of certification guides, they are often checked against the certification objectives. A self-published work has no such verification process.

NOTE Clearly, a few self-published works are very well written. However, self-published means it was not vetted by anyone other than the author. During a deposition or cross-examination at a trial, this issue will certainly come up.

Item c may seem even odder. The fact is that in many expert reports, there may be dozens of citations. The people reading the report, particularly a lengthy one, might not check carefully every citation. I have personally prepared expert reports that were close to 300 pages long with many scores of citations. It would certainly be possible to exaggerate or interpret the conclusions of one or more of those citations in order to enhance one’s position.

Violating item b or c of the AAFS code of ethics can have extremely deleterious effects on your career. When you testify in court, whether it be specifically as an expert witness or simply as a forensic examiner (for example, for a law enforcement agency), your only real commodity is your reputation. Any hint or suggestion of exaggeration may, in fact, end your career. You can read the AAFS code of ethics at http://aafs.org/about/aafs-bylaws/article-ii-code-ethics-and-conduct.

ISO Code of Ethics

The ISO standards for ethics are much longer—currently, a 92-page document—and are concerned with forensic testing and forensic labs. It would be worthwhile for you to thoroughly review this document, particularly if you intend to establish a new forensic lab or manage an existing forensic lab. However, in this section, we will highlight some specific issues you are likely to be tested on in the CCFP test.

Lab Accreditation

For labs, there is a somewhat lengthy accreditation process. That process includes an introductory visit, assessment of your practice, and document review. After this, you are given some time to plan for the actual accreditation visit. The formal accreditation visit may be followed with recommendations for corrective action that must be reviewed prior to an accreditation decision being made.

The accreditation will be concerned with your handling of the chain of custody, security of the evidence, procedures in place, precautions, and policies. Policies must address routine handling and security of evidence, as well as how to handle incidents such as a breach in security protocol.

Digital Forensics

Section 30 of the ISO code of ethics refers specifically to digital forensics. One important issue dealt with in this section is the use of outside contractors. Specifically, the ethical standards state

An agency may use the services of an outside party to perform aspects of digital and multimedia examination, but the agency must exercise caution in how the test results are reported so that accreditation is not incorrectly inferred for the tests in question.

This is very important. In any cyber forensics lab, you may encounter a case that requires forensic examination of some digital device with which you are not proficient. This may require the use of an outside contractor to examine that specific evidence. However, you are still responsible for ensuring that the outside contractor adheres to accepted forensic practices.

The ISO digital forensics ethical standards also address the issue of learning new skills. Specifically, the standards state that

In circumstances where examiners attend classes, seminars or conferences to learn new analytical techniques, agencies shall take measures to assure themselves of the competency of the examiners prior to authorizing them to apply these techniques to case work.

This is also quite important. New technologies emerge, and new tools are developed. At some point, your forensic staff will need additional training. However, how much training is required to make them proficient in this new technology or technique? The lab must have some means of ensuring these forensic examiners are indeed proficient in the new skill set before allowing them to use it on an actual case. Related to this is the requirement that a forensic lab must have a protocol in place for evaluating new technologies and techniques before implementing them. So both the new technology and the examiner being trained in that new technology must be evaluated.

Ethical Conduct Outside the Investigation

As was mentioned earlier in this chapter, a part of your job as a forensic investigator involves testifying. To be effective at testifying, you must have impeccable character. It is guaranteed that opposing counsel will seek out any issues that might impugn your testimony. Obviously, this means a clean criminal record; however, other issues are also important.

Civil Matters

Have you ever been sued? If so, for what reason and did you win the case? Obviously, anyone can be sued, and being the object of a lawsuit does not mean you are untrustworthy. So if you have been sued, be prepared to answer a few questions.

First, was the lawsuit related to your professional work? This sort of lawsuit is one of the most damaging for a forensic investigator. As a cyber forensic investigator, if you have previously been sued—for example, due to allegations of incompetent network consulting—opposing counsel may use that to suggest you are not really competent in computer science and your investigation should not be considered reliable.

If the lawsuit was not related to your professional work but involved issues that might indicate unethical behavior on your part, such as dishonest business practices, this, too, can be used to impugn your testimony. It is very easy for opposing counsel to make the argument that if, for example, you were accused of being dishonest when you sold your house, you might also be dishonest when you conduct a cyber forensic investigation.

As mentioned, anyone can be the target of a lawsuit, and being a defendant in a lawsuit is not an automatic end to your forensic career. The first issue at hand is, Does the lawsuit involve issues that could impugn your character? Then the next obvious question is, Did you lose the lawsuit? However, again, my rule is to err on the side of caution. If you find yourself the target of lawsuits repeatedly, then you probably should take some time to seriously review your conduct to determine why you are being sued so often.

Criminal Matters

It should be fairly obvious that any history of criminal behavior will normally end your career in cyber forensics. But there are always exceptions. For example, if you had a misdemeanor charge when you were a youth and you are now middle aged, it is most likely you can explain that charge and move forward with your career. However, a general rule is that any sort of criminal charge, including reckless driving, misdemeanor assault, trespass, etc., is extremely detrimental to your career.

In general, criminal conduct is simply not acceptable. If there is any criminal charge in your background, even if it was a misdemeanor and was 20 years ago, you need to disclose this to the attorney you are working with or to senior investigators/supervisors. Someone in authority must be made aware of the details of the criminal act, including the outcome. This will allow that person or persons to determine if this prevents you from being an effective forensic investigator.

Other Issues

We live in an information age. Everything is public and it is very easy to find. You have to remember that cyber forensics is usually related to some court case, whether criminal or civil, and our legal system is adversarial. It is very likely that opposing counsel will perform a web search on your name in an attempt to find information that might be embarrassing. If you posted a picture to Facebook showing you inebriated at a New Year’s Eve party, this is something that opposing counsel could use to embarrass you.

You should be very wary of anything you put on the Internet. It is okay to have a Facebook page (I have a personal Facebook page for friends and family and a public one for readers and fans), but the rule is simple: Do not post anything you would be embarrassed to see in a courtroom. Even political statements/opinions, if worded wrong, can be perceived as offensive.

Any professional opinion you make in public will come back to you. Something as simple as book reviews you write on Amazon.com can be used in a deposition or trial. For example, if you give a glowing review of a Linux book on Amazon.com, and the opposing expert is citing that book in his or her report, the opposing counsel will use your review to indicate that you must agree with their expert.

I am not saying that you cannot make public statements. Many experts do book reviews, write articles/books, and even speak at conferences. The key is to be very sure of what you write or say, being aware that it can come back to you in a later case.

Ethical Investigations

Ethics in your conduct of your investigation is critical. A number of issues may arise during an investigation that you need to be aware of. Before we begin a discussion of ethical investigations, it is important to differentiate between ethical and legal. Legal indicates that your investigation followed the letter of the law. Ethical indicates that you strove to maintain the highest standards and to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. The law does not require that you avoid even appearing to engage in misconduct. However, you must keep in mind that evidence is usually used in court proceedings, which, as mentioned, are adversarial in nature. This means that there will be opposing attorneys (and probably their own forensic expert) who will attempt to cast doubt on your investigation and your conclusions.

The Chinese Wall

There may be occasions when different members of the same firm are working on cases that could present a conflict of interest if those investigators shared information. This sometimes occurs with law firms. For example, one attorney represents company XYZ, Inc., and another represents ABC LLC.; however, at some point, XYZ files a lawsuit against ABC. Now the attorneys have a potentially serious problem of conflict of interest.

The Chinese Wall is a procedural barrier that prohibits two members of the same organization or team from sharing information related to a specific case or project. This can be more cumbersome than it sounds. The two people involved in a project or case that could lead to a conflict of interest must be prevented from communicating any information about that case, no matter how trivial. Furthermore, other people in the organization must also ensure they don’t accidentally reveal inappropriate information to one of these two members.

TIP The Chinese Wall concept is something that is part of the CCFP exam. It is rather simple, but make sure you can apply it to scenarios.

Relevant Regulations for Ethical Investigations

Clearly, if ethical conduct outside the investigation is important, then ethical conduct within the actual investigation is critical. Conducting an investigation in an ethical manner is just as important as following the legal guidelines. There are several issues to consider, as the following sections explain.

Authority to Acquire

Do you have the authority to acquire the evidence? This may seem like an odd question, but it is important. As mentioned previously, in many states, it is illegal for evidence to be seized by anyone who is not a law enforcement officer or a private investigator.

Provenance

Provenance is defined as the origin of something. For example, in art, the term refers to evidence showing that a given piece of art is actually the work of a specific artist. For example, was a Monet painting actually painted by Monet? In forensics, provenance has a very similar meaning. If it is alleged that a given file originated with a suspect’s computer, can you show clearly that it was actually from that suspect’s computer? If a child pornography website is accessed from a computer to which multiple people have access, for example, it will be more difficult to show that the suspect actually accessed the website.

Reliability

Is the evidence reliable? Is the evidence from a source that is reliable? For example, if someone brings evidence to the police, reliability is immediately a question. If evidence does not come from a reliable source, then it is not possible to base conclusions on that evidence.

Admissibility

Admissibility may seem similar to reliability and provenance, and they are related topics; however, they are not identical. This area of ethical consideration is far more related to legal guidelines in evidence. We discussed chain of custody at the beginning of this chapter, and you must keep that in mind throughout your investigation.

Fragility

The issue of evidence fragility is more related to how and when you collect evidence. In subsequent chapters as we discuss the gathering and processing of evidence, we will delve into this issue in more detail. An example would be spyware that is running on a live system. This is volatile evidence that might be lost if you turn off the computer without first recording the evidence. Yet another example involves active network connections to a suspect machine. These will definitely be lost when the machine is powered down; therefore, that evidence is considered fragile.

Authentication

Authentication is closely related to provenance and chain of custody. It refers to the ability to verify that the evidence is what it is claimed to be, was gathered in a reliable manner, and chain of custody was maintained. This will involve documentation of how the evidence was found, how it was seized, and the validation of drive images that are made for the investigation (something we will be discussing in detail).

The Evidence

When considering ethical guidelines for an investigation, the evidence itself can be an important guide to how to ethically handle the investigative process.

Criminal Investigations

Conducting a criminal investigation involves adhering to specific legal requirements. These legal requirements should also form the basis for ethical rules. The most obvious legal requirement in the United States is the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Fourth Amendment states

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

This seemingly simple statement is the basis for a great deal of case law regarding appropriate searches and the seizure of evidence. One question that has been the center of a great many court decisions is what constitutes an unreasonable search or seizure. U.S. courts have consistently held that for a search to be reasonable, either there must be a warrant issued by a court, or there must be some overriding circumstances to justify searching without a warrant.

Let’s deal with the issue of warrants first. A warrant is essentially legal permission to seize evidence. This leads to the question of what constitutes a seizure. According to the Supreme Court, a “‘seizure’ of property occurs when there is some meaningful interference with an individual’s possessory interests in that property,” United States v. Jacobsen , 466 U.S. 109, 113 (1984), and the Court has also characterized the interception of intangible communications as a seizure. This is very important. A seizure occurs simply by preventing the suspect from being able to interact with his property. If you were, for example, to prevent the suspect from using his laptop computer, you have just legally seized that computer.

While there are exceptions to the requirement for a warrant, it is almost always best to get a warrant before seizing any evidence. There are two exceptions. The first is exigent circumstances, which usually does not apply to cybercrime. This refers to police entering a dwelling or seizing property to prevent imminent harm. For example, if an officer hears someone screaming “HELP” from an apartment, the officer does not need a warrant to enter the apartment. This would rarely apply to cybercrimes. However, the second exception might apply. The second exception is called plain sight. This means that if something is in plain sight, you don’t need a warrant. For example, if a police officer is at a home responding to a noise complaint and can clearly see child pornography on a computer screen, the officer does not need a warrant.

Civil Investigations

Civil investigations center on lawsuits. A lawsuit involves the allegation of wrongdoing where the potential damages are financial rather than criminal. Civil litigation includes wrongful termination lawsuits, patent infringement suits, copyright infringement suits, and similar litigation. These cases will sometimes involve forensic examination of evidence.

For example, in the case of a sexual harassment lawsuit, it may be required to forensically extract and analyze e-mails. The process will be very much the same as it is with criminal investigations. The exact same issues with chain of custody and with documenting your process are involved. One major difference is that in a civil investigation, it is usually the case that a company owns the computer equipment and can provide permission to extract and analyze evidence; thus, warrants are unlikely to be needed.

Administrative Investigations

Administrative investigations are usually done strictly for informative purposes. These are not meant to support criminal or civil court proceedings. For example, if there is a system outage that causes significant disruption to business, management may want to have a forensic investigation performed in order to ascertain what caused the outage and how to avoid it in the future.

One might think that the normal processes used in criminal and civil investigations are not needed in this situation. And to some extent, this is true. Certainly, a warrant is not needed to seize evidence and examine it, provided the evidence belongs to the party requesting the investigation. For example, a company does not need a warrant to search company-owned computers. Furthermore, civilians cannot request search warrants. However, even if this is an internal forensic investigation for a company, it is still critical that you document every single step. There are two main reasons for this. The first is simply to accurately document the investigation in order to clarify and support any findings. The other reason is that it is possible an administrative investigation could lead to a criminal or civil investigation. For example, assume that you are investigating the reasons for an e-commerce server being offline for two days. In your investigation, you discover that the problem lies with a third-party company you use for application development. Management may wish to initiate civil litigation in order to recoup losses. This will not be possible if you have not followed sound forensic practices.

In other cases, evidence may reside on someone else’s machine, but in a civil case, you do not get a search warrant. Instead, the attorney will file a motion to the court asking the court to order the other party to produce the evidence.

Intellectual Property Investigations

Under the topic of civil investigations, we mentioned patent lawsuits. Patent litigation and other intellectual property investigations are handled a bit differently than criminal investigations. To begin with, there is usually not a seizure of evidence. Instead, the court will order the defendant to produce the evidence to the plaintiff. The plaintiff will designate an expert to examine the evidence and reach some conclusion. The discovery process can be lengthy. It is common for defendants to take one of two approaches. The first is to produce as little as they believe will fulfill the court’s order. This usually leads the plaintiff to make additional requests for discovery. The second tactic is to simply dump everything they have on the plaintiff, giving the plaintiff literally a mountain of evidence to sift through.

It is also often true that intellectual property investigations can be lengthy. One reason is that defendants often overproduce evidence. What I mean by this is that when the court orders the defendant to produce, for example, source code to a program, the defendant may produce all their source code, with no notes, no direction, and no indication of what it does. The expert then must take the time to first figure out what the code does and then determine if it violates the plaintiff’s intellectual property rights.

NOTE Normally, the defense will produce the required evidence in a secure room at their attorney’s office. The plaintiff’s expert then goes to that office and examines the evidence. This is often time consuming. On one particular case, I spent six months examining the code to make a determination. The defendant had produced over one terabyte of completely undocumented code.

An important part of patent litigation is the Markman hearing. In a patent infringement case, there is usually disagreement among the opposing attorneys as to what specific terms of a patent mean. This may sound like frivolous arguing, but it certainly is not. For example, what exactly constitutes an “applet”? Some programmers might say that an applet is a piece of self-contained Java code that executes within a web page. However, in a patent case, the terms have meaning based on what the inventor stated in the patent. The actual wording of the patent is called intrinsic evidence ; supporting material from third-party sources is called extrinsic evidence When the two parties disagree as to the definitions of words, each side prepares an argument for their position and submits it to the court. The court then has a Markman hearing to determine the definitions of the disputed terms. This is important for a forensic expert, as you must use the definitions the court has chosen even if they might be different from those commonly used in industry.

The Daubert Standard

One very important legal standard to keep in mind during any investigation is the Daubert standard. The Daubert standard essentially states that any scientific evidence presented in a trial has to have been reviewed and tested by the relevant scientific community. For a computer forensics investigator, that means that any tools, techniques, or processes you utilize in your investigation should be ones that are widely accepted in the computer forensics community. You cannot simply make up new tests or procedures. Harvard Law School6 describes the Daubert standard as follows:

The Supreme Court’s decision in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals is often thought of as two separate holdings. (1) In the first, unanimous holding, the Supreme Court asserts that the long-standing Frye rule for the admissibility of expert testimony has been replaced by the more recently enacted Federal Rules of Evidence. (2) This holding has been generally well received and universally applied by the federal district courts. The second holding, however, has been a source of great confusion and controversy. In the second part of the Daubert decision, over the dissent of Justices Rehnquist and Stevens, Justice Blackmun writes that federal judges have a duty to ensure that ‘an expert’s testimony rests on a reliable foundation and is relevant to the task at hand.’ (3) In addition, Justice Blackmun lays out a number of criteria by which the reliability of an expert’s testimony may be judged. (4) While it is clear that the majority of the Court envisions a more active gatekeeping role for federal judges, it is not clear exactly what the limits and scope of that role should be. Perhaps most significantly, it is uncertain whether this more active judicial role applies only to determining the admissibility of ‘hard’ scientific evidence, or whether the Daubert decision is to be used to evaluate the admissibility of non-scientific and quasi-scientific expert testimony as well.

The Forensic Investigator as an Expert

As previously mentioned, forensic analysts/investigators will often serve as expert witnesses in trials. An expert witness is a bit different from a witness of fact. An expert witness is allowed to testify about things he or she did not see. However, the expert’s testimony must be firmly grounded in accepted scientific methodology. In other words, the expert witness did not “witness” something occur, but rather forms opinions based on his or her expertise. Those opinions must be firmly grounded in scientific principles and evidence.

NOTE What is the difference between an expert witness and a forensic investigator? Sometimes, nothing. An expert witness is simply someone who has been hired to form opinions about a case and who has relevant expertise. We will discuss the qualities you may want in an expert, but there is no firm line. I have personally seen people with doctorate degrees and those with only bachelor’s degrees serve as expert witnesses. A lot depends on the individual case and the totality of the person’s expertise. Of course, the more qualifications one has, the better. Opposing counsel can file a motion with the court objecting to the expert, particularly if they believe the expert lacks appropriate expertise or has a conflict of interest.

Qualities of an Expert

If someone is going to testify at depositions or at trials, it is important that they have certain qualities. Not everyone who is an expert in a given field is appropriately used as an expert. Even qualified and credible experts might not be appropriate for every case. For this reason, there are specific qualities that should be considered:

• Clean background check

• Well trained

• Experienced

• Credibility

• No conflicts

• Personality

TIP Remember that the opposing side in any trial, be it criminal or civil, will try and attack your expert witness’s credibility. It is important that his or her professional qualifications be such that a jury will clearly accept their expertise.

Clean Background Check

It is absolutely critical that anyone working with computer crime investigations have a thorough background check. That may seem obvious, but there are plenty of companies that don’t do any background checks on their employees. For law enforcement agencies and Department of Defense−related organizations, the background issue is already taken care of. However, when dealing with civilian employees and consultants, a criminal background check should be conducted and updated from time to time. It is probably best to make sure that any civilian consultant has the same level background check given to law enforcement and is held to the same standard.

You may think that anyone working in information security has had a background check. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Sometimes, companies either do no background check or only a cursory one. I personally encountered an Internet Service Provider whose technical support manager had twice been in federal prison, and on both occasions had identity theft as one of his offenses. This means you cannot assume that an experienced professional has a clean criminal background.

Well Trained

Obviously, in order to be an expert in any field one must have significant training. That training can come from a variety of sources, including traditional academic degrees, job-related training, industry training, industry certifications, webinars, and continuing education.

Academic Training and Programs If one is to serve as a testifying expert, it is best to have a graduate degree. It is certainly possible for one to have only a bachelor’s degree, or even no degree, but a graduate degree is ideal. The degree should be in some related field such as computer science, computer information systems, or computer engineering. These academic programs ensure that the individual has a thorough baseline understanding of computer systems, operating systems, networks, programming, and related topics. It is certainly possible to have a degree in a different discipline, depending on other factors. For example, someone with a business degree might have taken a great many computer-related courses as part of their degree. Or someone with a degree in history might have combined that with extensive experience in the industry and industry training.

The nature of the academic training is also important. Obviously, you won’t always be able to find an expert with a doctorate from a prestigious institution such as Harvard, Princeton, or Midland; it is not necessary. What you need is for the totality of that person’s qualifications to make them clearly an expert on the topics that they need to testify about. It is important to make certain the institution the expert’s degrees are from is regionally accredited. That may seem odd, but there has been a proliferation of spurious degrees, particularly online degrees. This is not to say that an online degree is illegitimate. Harvard, MIT, Stanford, Texas Tech, University of North Dakota, North Central University, Capella University, and American Military University all have fully accredited, recognized online programs. Whoever is hiring an expert should check the accreditation of any degree program.

It is also important that the expert be a learner. That means two different things. The first, of course, is that the expert must learn each new case, carefully studying all aspects of it and learning its nuances. This is the way the CCFP uses the term “expert as a learner.” However, I would opine that it also means the expert must be continually learning. Even if one has a PhD in computer science from MIT, one should still refresh and expand one’s learning from time to time. If you see an expert whose resume does not indicate any new learning in the past ten years, this should be cause for concern.

Certifications Industry certifications are a significant part of the computer industry. Microsoft Certified Solutions Expert, Red Hat Certified Engineers, and Java Certified Programmers are all part of the IT profession. And the same is true with the security profession. There are a number of certifications relevant to IT security and forensics that might be of interest to you in selecting a consultant or expert witness. It should be noted that the (ISC)2 certifications have gained wide respect in industry; thus, pursuing the Certified Cyber Forensics Professional certification from (ISC)2 is definitely an indication of expertise. The ideal situation is when certifications are coupled with degrees and experience—then they make a powerful statement about the person’s qualifications.

Experienced

Training and education are important, but frankly, experience is king. It is certainly valuable to have obtained training, but it is just as important to have actual experience. When someone is seeking a computer crime expert or consultant, they want someone who has real-world, hands-on experience. Now it may or may not be necessary to find someone who has investigated computer crimes. That may sound like an odd statement, and obviously, you would prefer someone with experience investigating computer crimes. However, someone with a strong understanding of investigation and forensics who has extensive experience in computer systems and networks can be a useful asset. That knowledge of operating systems and networks can be as important as, if not more important than, investigation experience. Of course, the ideal candidate will have both skill sets. But in no case should you use someone who has only academic training and has never functioned as a network administrator, security administrator, network consultant, or related job.

The obvious counterargument to this is that there is a first time for everything. Even the most experienced professional once had their first investigation. Ideally, however, that first investigation will involve assisting someone with more experience. You certainly do not want your case to be their first real-world attempt. If you are going to utilize an expert, it is important that they have experience, not just extensive training. And the more experience they have, the better.

Credibility

In most trials, both sides will have an expert witness, and most expert witnesses will have significant training and experience. Another issue that is important to keep in mind is credibility. This may be academic or professional credibility. How do you know if a particular individual has that credibility? To a layperson, simply having an advanced degree would seem to be evidence enough, but that is not the case. One needs to have contributed meaningfully to that particular academic discipline. That can mean any number of things. It is often evidenced by particular awards, such as endowed chairs at universities. It also can be evidenced by publications of both research papers and books.

A good indicator of expertise is how often other experts refer to their work. If you find no other researchers reference a person’s work, that is a strong sign that their work is not considered credible or noteworthy by their professional peers. You can do a Google Scholar search on an author’s name to see how often that person’s works are cited by other experts in the field. However, even if an expert has not published books or research papers, they may still be a qualified expert. The expert is a technician in the specific field on which they are opining. This requires training and credibility.

No Conflicts

It is absolutely critical that your expert have no conflict of interest. When law firms are considering experts to use in a case, one of the first things they check for is a conflict of interest. This means the expert witness should have no prior business or personal relationship with any of the principal parties in the case. In civil litigation, this means the expert should have no prior relationship with the plaintiff or the defendant. In a criminal case, it usually just means the defendant, since the plaintiff is the state. What exactly constitutes a prior relationship? In most cases, this means no substantive contact, that the two parties do not know each other on a personal level or have business contacts. Some attorneys are even stricter and require that the expert to have never even met the involved parties and to have no direct communication with them outside of courtrooms and depositions. Remember that for better or worse, our legal system is adversarial. If there is any way the opposing counsel can construe the expert as being biased, they will do so. For this reason, it is best to avoid even the appearance of any relationship with any relevant parties.

Conflict of interest goes beyond direct relationships between the parties. It literally means that the expert has some interest in the outcome of the case. Ideally, an expert’s only interest is in the truth. He or she should have no personal motive in seeing the case decided in favor of one party or the other. For example, an expert witness for the prosecution in a case involving child pornography might be considered to have a conflict of interest if someone close to them has been a victim of child pornography. Or an expert for the defense might be considered to have a conflict of interest if that expert is a member of the same fraternity, church, or social group as the defendant.

NOTE Remember the appearance of a conflict of interest can be enough to change the outcome of a trial. Therefore, one must carefully screen potential expert witnesses for conflicts of interest.

Personality

We have discussed the technical specifics to look for in an expert. But what issues are not found on a resume that might make a good (or bad) expert? These issues are important in any expert, but are most important in a testifying expert witness. Teaching ability is important. The expert witness will need to explain complex technical topics to a judge and jury. This requires someone who is skilled in communicating ideas. This is why lawyers often use professors as expert witnesses—they are comfortable teaching and speaking in front of groups. The expert is ultimately a teacher. Of course, you don’t need to be a professor to be an expert witness, and many expert witnesses are not professors. But you do need to be able to teach.

A calm demeanor is also important. The fact is that a deposition or trial is bound to be stressful for the witness. In addition, some attorneys will endeavor to unsettle an expert witness, particularly during deposition. Remember that the other side’s attorney is going to question the expert’s credentials, methods, and findings. They may even question the expert’s integrity. Someone who is easily upset will likely have a strongly negative reaction to this. The expert must be calm, confident, and not easily upset.

Another issue to be aware of with an expert is their history of testimony and expert reports. Have they previously testified to or made a public opinion that could reasonably be construed as contrary to the opinion they will be taking for you? For example, if an expert previously wrote an article stating that online sting operations to catch pedophiles are inherently unreliable, you cannot now use them to testify for you in support of evidence gathered in an online sting. Now this may seem obvious, and you may think that no expert would want to testify contrary to an opinion they previously espoused. However, it is an unfortunate fact that there are a few experts who indeed will say anything for a fee. So you (or the attorney handling the case) need to expressly inquire about this issue. It is important to note that the number of experts willing to say things they don’t believe for a fee is far lower than some elements in the public perceive, particularly in technical subjects where the elements of the case are relatively concrete and less open to interpretation. The majority of experts will simply turn down a case if they don’t agree with the conclusions that the client (in this case, you) wish them to support.

Related to past public opinions and testimony is the issue of honesty. Contrary to what you may have seen on television and movies, the vast majority of experts will not prevaricate in testimony or in their reports. Obviously, some issues are open to interpretation, even in technical disciplines, and some experts are more willing than others to take a more creative interpretation of the evidence. However, stating an outright falsehood, either through intentional lying or just being in error on the facts, is usually the end of an expert witness’s ability to function in court cases.

Chapter Review

In this chapter, we have examined legal and ethical guidelines for conducting forensic investigation. We have looked at U.S. law regarding the search and seizure of evidence and standards for admissibility of evidence, as well as general ethical guidelines. As important as the examiner’s ethical conduct during an investigation is the examiner’s ethical conduct outside of the investigation. Furthermore, we have examined the differing ethical and legal requirements for various types of investigations, including criminal, civil, administrative, and intellectual property.

Questions

1. What term describes the route that evidence takes from the time you find it until the case is closed or goes to court?

A. Law of probability

B. Daubert path

C. Chain of custody

D. Separation of duties

2. If a police officer locks a door without a warrant so that a suspect cannot access his (the suspect’s) own computer, what would be the most likely outcome?

A. The evidence will be excluded because the officer seized it without a warrant.

B. The evidence will be excluded because it does not meet the Daubert standard.

C. The evidence will be admitted; this is not a warrantless seizure.

D. The evidence will be admitted; the officer acted in good faith.

3. Which of the following is not part of the (ISC)2 ethics guidelines?

A. Obey the Daubert standard.

B. Act honorably, honestly, justly, responsibly, and legally.

C. Provide diligent and competent service to principals.

D. Advance and protect the profession.

4. Which of the following is a guideline for admissibility of scientific evidence?

A. The Daubert standard

B. Warrants

C. (ISC)2 ethical guidelines

D. The Fourth Amendment

5. According to the Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence Model Standard Operation Procedures for Computer Forensics, which of the following is not required for chain of custody.

A. Description of the evidence

B. Documented history of each evidence transfer

C. Documentation of how the evidence is stored

D. Documentation of the suspect

6. What is the process whereby a court determines the meaning of disputed words in an intellectual property case?

A. Deposition

B. The Fourth Amendment

C. The Markman hearing

D. The Daubert test

7. Which of the following would allow a police officer to seize evidence without a warrant?

A. If the suspect has a history of related crimes

B. If the alleged crime is a felony

C. If the evidence is in plain sight

D. If the officer has a good tip

Answers

1. C. Chain of custody, which is a critical concept you must understand for the CCFP exam. Chain of custody is documenting every single step the evidence takes from seizure to trial.

2. A. Yes, any interference with a person’s property is a seizure.

3. A. The Daubert standard is necessary, but is not part of the (ISC)2 ethics.

4. A. The Daubert standard is the rule that governs the admissibility of scientific evidence. Essentially, it states that the techniques and tests used must be widely accepted in the scientific community.

5. D. Documentation of the suspect is not part of the chain of custody.

6. C. The Markman hearing determines the definition of disputed terms.

7. C. If the evidence is in plain sight.

References

1. The Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence Model Standard Operation Procedures for Computer Forensics.

2. https://www.swgde.org/documents/Current%20Documents/SWGDE%20QAM%20and%20SOP%20Manuals/2012-09-13%20SWGDE%20Model%20SOP%20for%20Computer%20Forensics%20v3.

3. Section 7. https://www.swgde.org/documents/Archived%20Documents/SWGDE%20SOP%20for%20Computer%20Forensics%20v2.

4. (ISC)2 Code of Ethics. https://www.isc2.org/ethics/Default.aspx.

5. AAFS Section II code of ethics. http://aafs.org/about/aafs-bylaws/article-ii-code-ethics-and-conduct.