Chapter Seven

Plot the Middle

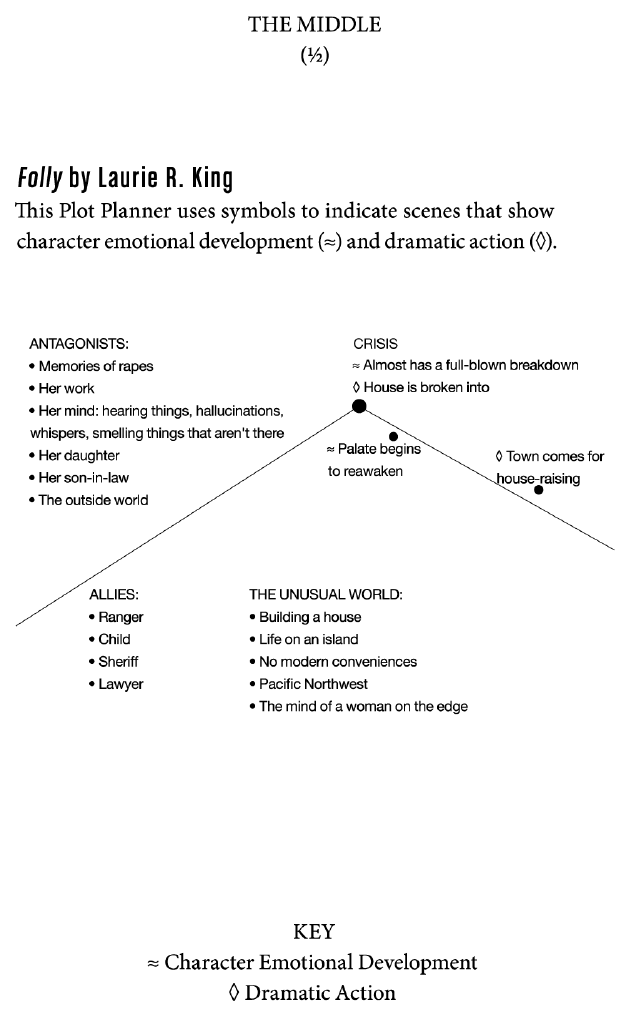

The middle of your book comprises approximately one-half of all of the scenes in your entire project. It is where the main action of your story takes place. Perhaps you left the beginning on a high note and launched enthusiastically toward the middle. You and your characters have now crossed into the heart of the story world. However, if you’re unprepared and don’t know how to proceed, the middle can seem like a long, empty expanse, like a huge wasteland waiting to devour you, the writer. The middle has stopped many good writers in their tracks.

The middle is especially difficult for writers because it requires them to create continually rising tension.

Writing the middle of a novel, memoir, or screenplay has a bad reputation. Granted it’s easy to get lost in the maze of subplots and secondary characters that populate the middle. Creating twists and turns in this portion of the story can make you dizzy. In your confusion, doubt can creep in, and you might question why you ever decided to take on such a project. The crisis awaits, and the thought of ripping the rug out from under the character you’ve grown to love makes you weep.

If you are like other writers, at this point you are desperate to return to the place of discovery. To ease your way out of the terror of the unknown, you might retreat to the beginning of the story and start again. You rationalize that just as soon as you incorporate all those loose ends, you will be better prepared to persevere to the End. Yet, inevitably, when you arrive at the point in the middle where you stopped before, you flounder yet again.

Sound familiar? Rather than rip the Plot Planner off the wall and stuff it in the bottom of your filing cabinet, I encourage you to keep at it. You probably believe that your story suffers a fatal flaw. That is not necessarily so.

I bring up the difficulty of the middle not to frighten you but to prepare you. After all, your attitude directly affects your energy as you write, which, in turn, affects the energy of your project. The last thing I want is to send your energy spiraling downward. Understand that when you hit a brick wall, it is not because of you. It is the nature of the beast.

To avoid hitting that wall, keep in mind the five primary goals of the middle. Look for opportunities in every scene in the middle of your novel, memoir, or screenplay to do the following:

- Deepen the protagonist’s character traits, both positive and negative, that you introduced in the beginning.

- Create an unfamiliar world that keeps her off balance.

- Develop secondary characters with goals at odds and in conflict with the protagonist’s goals.

- Intensify the uncertainty of the outcome and the dramatic question (“Will she or won’t she succeed?”) by intensifying the demands of her opposition.

- Show her learning new skills and being exposed to new beliefs that she’ll need to succeed in the End. She might not even consciously or fully understand how the skills will serve her in the future. These lessons and tricks should be part of the external plot of the middle and directly relate to one or more of the secondary characters as part of their shared subplots. The talents, powers, and moves obtained or taken by the protagonist should play into the plot in the final quarter of the story, but neither the characters nor the reader should know of their importance in the middle.

Following these guidelines for the middle of your story will help you show up, day after day, to write. You can devise some bumps and challenges that will interfere with the protagonist’s progress. Your page count might double as you expose your protagonist to new skills and talents that she’ll need for the End. You’ll begin to feel confident and excited.

A writer in one of my workshops once asked a fellow writer to stand up and hold out his arm sideways with his thumb pointing down. Then she instructed him to resist when she pressed down on his arm. He was able to keep his arm steady against the pressure.

Next, she asked him to think about something negative concerning his writing. This time, using the same pressure, his arm gave way, as if he had lost all of his strength.

Finally she asked him to concentrate on a positive experience or feeling. He was easily able to resist the pressure on his arm.

This experiment shows how negative emotions, like worry and doubt and criticism, affect our physical energy. It also illustrates the strengthening effect that positive thoughts and emotions have on us physically.

I encourage you to stay positive as you tackle the exotic world of the middle. Take a look at all of the scenes you have plotted out on the Plot Planner. Do not see the Plot Planner as half empty; see it as half full. The direction of your focus does not change the reality of the holes and gaps that are on your Plot Planner, but your attitude certainly changes your energy and enthusiasm to persevere.

Determination and perseverance are two key traits of successful writers. Stay determined. Persevere all the way to the end of your project. Until you reach the end, you will never truly know what you have.

The Anatomy of the Middle

The middle is where the real trouble for the protagonist begins. It must inject in the reader a strong desire to know what happens next. Sometimes the tension level in the middle starts at a lower place on the Plot Planner line than at the end of the beginning. This happens when the tension of the beginning drops slightly, having found a release by moving into the unfamiliar world of the middle. Also, the middle doesn’t always pick up where the end of the beginning left off. By beginning the middle with a time jump or a new location, a writer makes the end of the beginning even more definite.

Often, as a result of what happens at the end of the beginning, the protagonist enters the middle with a radically different goal than she started with in the story. The more specific these two goals are—the goal that informs the beginning and the goal she obtains from the middle onward—the better. These goals become plot beacons, and the protagonist carefully makes her way toward the blinking lights. Both goals are always just out of reach, thanks to obstacles that lead the character off track.

The middle is often known as the land of the antagonists. As we’ve discussed, antagonists are great tools for keeping the action high and increasing both tension and conflict. The protagonist encounters one antagonist after another, and conflicts and obstacles prevent her from reaching her long-term goal. Whether internal or external, when antagonists are in control, the protagonist is out of control, and, thus, the line on your Plot Planner moves upward. As soon as the protagonist overcomes one conflict, she is hit by another close call.

The Middle of the Middle

The middle of the middle is often where a new and unfamiliar world is deepened. However, even here, the Plot Planner line is not flat but continues steadily rising. Earlier in the middle, the tension may drop off as the protagonist experiences the new world she has entered. From this point on, as your protagonist ascends to the crisis or dark night, if the tension drops off for more than a scene or two, you are likely to lose the reader’s attention. Once the reader’s mind wanders away from the story, it is more difficult to lure him back into the story.

The protagonist leaves behind the life she knows for the unknown, and new and challenging situations arise. Self-doubts and uncertainty confront the character. She discovers strengths and struggles with shortcomings. She becomes evermore conscious of her thoughts, feelings, and actions, and the shifts from the life she has always known.

A band of antagonists control the middle: other people, nature, society, machines, and the inner demons of the character herself. The antagonists’ rhythmic waves of assault spur the protagonist’s vertical ascent. The unusual world continues to unfold, and the character begins to undergo a transformation on an inner level long before any observable changes appear.

Characters must make choices, and those choices must create conflict. Cliff-hangers and unexpected twists and turns reflect the rising action of the middle all the way to the crisis. If the plotline is a line of energy, the crisis is the highest point of dramatic action so far in the story, where the protagonist becomes more aware and sensitive. She begins to perceive and experience her life and the world around her in a new way.

Immediately after the crisis, the Plot Planner line falls, giving readers a chance to take a breather.

The Crisis

You will notice that the middle of the Plot Planner line culminates at a high point. This is the crisis, the highest point of tension and conflict in your story thus far and the lowest point in the entire story for the protagonist. This major turning point in the plot serves as a beacon to guide you through the middle.

Each scene in the middle portion of your story marches the protagonist one step closer to the crisis. The protagonist believes she is marching closer and closer to her long-term story goal, so when she gets to the crisis, she may be shocked. The reader, however, has experienced the steady march and feels the inevitability of this moment because of the linkage and causality between each scene and the constantly rising tension of story.

It is only in the darkness of a crisis in our lives—a failure or the death of a loved one or the breakup of a marriage or the loss of a treasured job—that we are forced to see ourselves as we truly are. Toward the end of the middle portion of your story, you want your protagonist to be confronted with her basic character flaw in such a dramatic way that she can no longer remain unconscious of her inner self.

This creates the key question: In knowing her flaw, will the protagonist remain the same or be changed to the core? You know as well as I do that in the heat of battle we say all sorts of things in our attempt to scramble back to our comfort zone. We make pacts with whatever power we believe controls our destiny. We promise to never be so foolhardy or curious or judgmental or angry, so long as we are able to go on, survive, make it past this horrible situation that has triggered such a life-changing wake-up call.

Of course, it is quite another thing to actually follow through on all those promises, once life settles down. For the purposes of your story, don’t worry about that yet. For now, all you need to do is create a scene that puts the protagonist in such an uncomfortable, potentially life-threatening or ego-threatening situation that she must finally see herself for who she truly is.

Of course, because the crisis is such a turning point in the story, fraught with tension and conflict and suspense, it has to be written in scene.

As you will note, after the crisis, the Plot Planner line drops for the first time. This is because after the intensity of the crisis, you want to give your readers an opportunity to rest for a moment, to digest all that has gone on thus far. This is a time for both your reader and your protagonist to reflect on what has transpired. This is a quiet time after the crisis. A story cannot be 100 percent struggle. But, as with other parts of your story, this rest period cannot go on for too long.

In All the Light We Cannot See, each chapter in the buildup to the crisis is comprised of one short scene filled with rising tension. The villain, Von Rumpel (who is more than an antagonist because his goal is not simply to block Marie-Laure from her goal but to take what Marie-Laure has) enters the apartment building where Marie-Laure had lived with her father before the invasion and uncovers an important clue to the whereabouts of the object he desires. In the next chapter, Werner, who has become known for his ability to locate enemy transmitters, spots a young girl singing a song he recognizes from the Children’s Home where he grew up. Soon after he targets a transmission incorrectly, and as a result, the young girl and her mother are shot and killed. Of the hundred men Werner is responsible for having killed, he is haunted by these two deaths. In the next short scene, a telegraph goes out requesting Werner to go to Saint-Malo, where Marie-Laure lives in the tall house on the shore and enemy transmissions have been detected. That chapter is followed by a summary telling of the first bombs to hit Saint-Malo. In the next chapter, we find Marie-Laure trapped in her house with the villain.

Each of these short scenes builds tension and brings the war and Werner to Marie-Laure. Werner’s crisis served to open his eyes to the senseless killing and his part in the slaughter. Marie-Laure’s chapter shows her starving and later taking actions that she knows will alert the villain to her whereabouts, which demonstrates her willingness to sacrifice herself for the good of the cause.

Plot the Middle

Plot the Middle

It is time to create the middle portion of your Plot Planner. To get started, retrieve the numbers you generated in chapter three, as well as the Plot Planner you have already begun.

If you have written a rough draft, count the scenes that occur after the end of the beginning, stopping at the number of middle scenes you calculated in chapter three. (For instance, if you calculated thirty scenes for your middle, count out thirty scenes in your rough draft, starting with the scene just after the end of the beginning.) Take a look at where that number puts you in the story. Is this scene the best stopping point for the middle? Does it pop out at you for its high dramatic action? Is it a scene where character emotional development is at its peak? If not, look to the scenes that come before and after. You are looking for the highest point of tension and conflict in the story so far, a true crisis for the protagonist. This scene is the character’s darkest moment, her greatest loss, her worst setback, the final blow, the most severe betrayal. Find it? Use that to end the middle of your Plot Planner, even if the scene comes a bit before or after the scene number you counted to. The parameters we set up in chapter three are guidelines only; you don’t have to follow them exactly. For now, decide where you believe the middle portion of your story begins (immediately after the end of the beginning) and ends (usually one to five scenes after the crisis).

Unroll twice as much banner paper for the middle as you did for the beginning. Continue the line you started for plotting, making it sweep steadily upward. About six inches from the end of this portion of the banner paper, drop the line down about six inches.

Now start plotting your scenes!

Do not fall into the trap beginning writers often make: Never summarize where a scene is needed.

Raise the Stakes

Support the middle with overarching tension by increasing the stakes. For instance, while the protagonist is waiting to hear about whether she will receive funding for an animal preserve before the bank forecloses on her land, torrential rains flood her home and destroy the property. Now that she has nothing, how can she possibly save the animals? When the reader knows something significant is at stake, like the lives of the animals, and that the outcome will be revealed later in the story, he is willing to wait and first learn more about how the exotic world of the middle operates before the physical, psychological, and spiritual crises ensue.

The Detailed Middle

One trick to developing scenes for the middle is to develop a subplot around the details of a unique task, job, or setting within the action. Subplots help to reinforce the overall meaning of the story. Readers like to learn new things when they read. For instance, many of the middle scenes of The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd involve the processes and trappings of beekeeping. Within the context of the plot, the reader learns all sorts of details about bees and honey while at the same time comes to a deeper understanding of the characters. Similarly the middle of Balling the Jack by Frank Baldwin is filled with inside information into the world of high-stakes dart games. E. Annie Proulx sets her novel The Shipping News in a remote location that many readers may never have considered: the Newfoundland coast. She fills her scenes in the middle with details of the world of shipping, the tides, and newspaper writing.