Chapter Five

Plot the Beginning

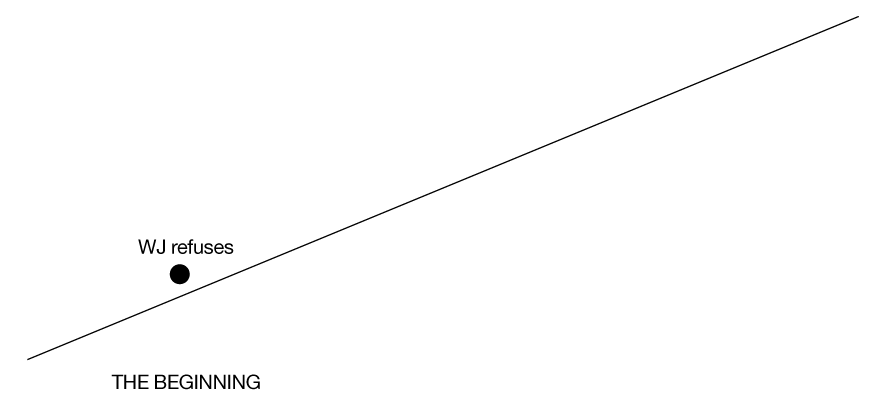

When plotting the beginning of your story, you will need to determine which scenes fall above and below the Plot Planner line. Determining whether the protagonist or antagonist(s) is in control in a given scene helps you decide where each scene belongs on the Plot Planner.

As we discussed earlier, scenes in which the dramatic action shows an antagonist controlling or holding the power over the protagonist go above the line. For instance, if the first scene shows the protagonist prevented from doing something she desires because of her insecurity, then the antagonist (her own flaw) is in charge, and that scene goes above the line.

Conversely, scenes in which the protagonist is in control belong below the line. These scenes are necessary to introduce the strengths and loves and dreams in her emotional development at the beginning of the story. If, in the first scene, the protagonist is in charge of the situation, or is at least not particularly threatened in any way, then scene one goes below the line.

Below-the-line scenes also give the reader a chance to take a breath after a particularly demanding dramatic action scene. But at their core, these scenes lack power and vitality. If you have too many of them in a row, you will put your reader to sleep.

Begin the story above the line with some sort of tension or an unanswered question, and your reader will immediately be drawn into the story.

Example

Before you dive in and begin plotting your beginning, let’s take a look at how this works in action. In Where the Heart Is by Billie Letts, Novalee, the protagonist, is seventeen years old, seven months pregnant, and superstitious about the number seven. In the first few scenes, the antagonist is her boyfriend, Willy Jack.

The book opens in scene with Novalee and her boyfriend on their way from Oklahoma to California. Novalee needs to stop to use the bathroom, but they have already stopped once for the same reason, and Novalee knows it is too soon to ask again. Tension mounts as her bladder causes her more and more discomfort and, eventually, pain.

Because this scene is rife with tension, and because Willy Jack holds the power, rather than Novalee, scene one goes above the line on the Plot Planner.

The scenes you include above the line in the beginning pages help ensure your readers’ commitment for the entire story. Make sure these above-the-line scenes are tightly linked by time and by cause and effect; this allows the reader to sink easily into your story.

In the next scene, Novalee awakens from a dream to find that her shoes fell through the rusted-out hole in the floorboard of the car. Willy Jack agrees to stop at a Wal-Mart to replace the shoes. After Novalee uses the bathroom, she buys some rubber thongs and receives $7.77 in change. She runs outside and discovers that the car and Willy Jack are gone.

This scene, scene two, also goes above the line, because although Novalee starts the scene in control of the situation, the scene ends in disaster.

In the next several scenes, Novalee meets three people, each of whom will play a part in her life as the story progresses, though readers do not know this at the time. Characters are best introduced in the beginning in order of their importance to the story. In this story, these three characters quickly become pivotal to her plot.

Not much happens in these scenes. This is a risky way to go about the start of a story; we are only on page 17. Usually the writer keeps things moving in the beginning of a project to entice the reader into the dreamscape of the story. However, in this case, slowing down works because there is so much tension hovering over the story.

The fact that Novalee is pregnant, in the middle of nowhere, and has only $7.77 adds suspense to the broader dramatic question (Will she or won’t she succeed?) to carry these quieter scenes.

The reader flips the pages to learn how this young girl is going to take care of herself. Each time Novalee meets someone, the reader waits for her to ask for help, and each time Novalee keeps quiet, the tension builds ever higher.

The presence of a “looming unknown” makes it possible for you to slow things down without the fear of losing your readers.

Plot the Beginning

Plot the Beginning

With your Plot Planner in front of you, decide which of your scenes, either already written or simply imagined, go above the line and which ones go below it. If your first scene has tension and conflict, or if the power is with someone or something other than the protagonist, jot a short note for this scene above the line on the Plot Planner, e.g., “Novalee abandoned.” Sticky notes work well for this task because they come in different colors and shapes, which you can use for identifying different plotlines, and they allow you to move and rearrange scenes quickly and easily.

If there is no tension or conflict in scene one, then the scene sticky note belongs below the line.

Now move to the next scene. Does scene two go above or below the line? Write it in. Continue in this way. Stop when you’ve written your scenes or scene ideas for the turning point of your story, the end of the beginning. Once you are finished with the scenes in the beginning portion of your book, stop and take a look at how they are arranged on the Plot Planner.

If most of your scenes are above the line, you can be confident that there is enough dramatic action to keep your reader turning the pages to find out what happens next. If, however, you find that most of your scenes are below the line, you could be in trouble. There is no rule for how many scenes belong above or below the line; however, if too many scenes in a row are below the line, it could mean that your story is too passive, too flat, and contains too much telling. Your story may not contain enough excitement for the reader, nor enough tension or conflict.

Many scenes that belong below the line are filled with internal monologue and, thus, are inherently nondramatic, with little action. Internal conflict is essentially nondramatic in that it cannot be played out moment by moment on the page. Do not get me wrong—internal conflict is essential for depth. But external dramatic action shows the degree of conflict and makes the scene. Scene, in turn, makes the story.

Tension in the Beginning

If you are like most writers, you probably find that the beginning scenes are the easiest to generate. As you plot beginning scenes on the Plot Planner, you might be pleased to find that the tension rises and that these scenes reveal a nice flow in cause and effect.

You should note that the line of the Plot Planner is not flat but climbs steadily higher. This corresponds with the rising tension of your beginning scenes. Much more is at stake in scene ten than in scene one.

As you plot the beginning, make sure your protagonist is an active participant in her own story. Novalee is a sympathetic character because she is, at her core, a good person attempting to do the right thing. She is also a survivor. This is important—the protagonist of a story cannot be passive. As the tension and conflict continue to rise, the protagonist must demonstrate that she can pick herself up off the floor time and time again. No matter how bad things get, find a way to make them even worse—and make sure your protagonist rises to each challenge.

If the protagonist is in worse shape at the end of a scene than at the beginning, you—as the writer—are in good shape. The emotion of the scene is constantly changing and the tension remains high.

Sharing Information and Backstory with the Reader

Writers, especially beginning writers, often are tempted to blurt out everything up front. This results in flashbacks popping up early on in the story in order to reveal the character’s backstory or the event that first sent the protagonist off-kilter.

My advice: In the beginning, pace how much information you share with the reader and refrain from using flashbacks. Short memories are fine, but try not to move back and forth in time. Rather your main objective for now is to ground the reader in the here and now of the story, where the main action takes place. In each scene, especially in the beginning, put in only as much information as is needed to inform that particular scene. (This can include foreshadowing clues of what is to come, but don’t overload the scenes with such details.) Invite the reader in slowly but with a bang. Keep curiosity high to create a page-turner!

The first quarter of any writing project introduces the story’s major characters, their goals, the setting, time period, themes, and issues. This is not the place where you necessarily deepen the character or the plot; it is the place of introduction.

When I say to introduce the familiar—such as characters, habits, the setting, or the character’s thought patterns—do not confuse introduction with passivity. Draw in the reader with dramatic action that calls for conflict, tension, suspense, and/or curiosity.

Once you have plotted out your beginning scenes, re-evaluate the end of the beginning scene you determined in chapter four. You want a scene(s) that cause substantial experiences:

- a separation from life as she has always known it

- a shift in her life circumstances or belief system

- a fracture in her primary relationship(s) (with others and even with herself)

Plot the effect as the protagonist leaves everything behind at the end of this beginning portion of your Plot Planner line. At the end of the beginning, there is no turning back. The protagonist crosses into the middle.

Keep Writing

If the activity above stimulates ideas and answers for your story, go back to the actual writing. Even when you lack the energy for writing, continue to show up each day. Instead of turning on your computer, turn to your Plot Planner.

My intention is to expose you to guidelines that work so that when you break the rules, you do so deliberately to achieve a specific result.