For decades, career-conscious middle managers have been encouraged to "manage" their relationships with their own supervisors with as much, or perhaps even more, care than they gave to managing employees. The idea was that you should do whatever you could, within propriety and proper protocol, to stand out from the crowd. The goal was prominence; to become, literally, the most outstanding among equals.

Today, it's the tallest daisy that gets cut first. Achieve too much prominence and you can become a threat to your boss. Stand out from the crowd and you make yourself a target, not only for backstabbers and fearful supervisors, but for bean counters and cost cutters as well. All employment is fleeting, so it's better to stay off the radar than to become too visible.

The idea now is to strive for success, not prominence. Do your job well and make your boss look good. Let him or her become prominent, if that's what they want. They can become the face for your superior results. Be the number-one producer who only attracts attention when the latest sales figures are released. The place you want to shine is on the spreadsheet, not the golf course. Keeping your head down and getting results are the best ways to make yourself valuable and nonthreatening to your boss.

The first area in which you can apply this approach is in talking to your boss about problematic projects. Work project issues are perhaps the most common of all those covered in this book. But that doesn't make them either routine or simple. Projects are, after all, the essence of what our jobs are all about. We largely base our perceptions of our employees on the way they deal with the projects we've assigned them. And our own employers base their perceptions of us on how we deal with the projects we've been assigned. Most projects become routine for those whose job it is to work on them. It's the rare problematic projects that take on disproportionate importance in how our performance will be judged and how we judge the performance of others.

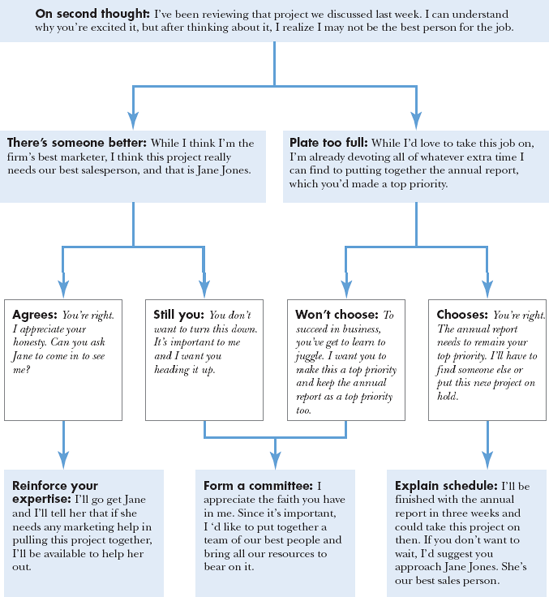

Avoiding a negative judgment is very difficult if you decide you need to turn down an assignment. This can be a no-win situation: say it's a bad idea and you could insult your manager, who may have been the person who came up with the idea; say you don't have the time and your manager could think you're lazy; and if you say you don't have the skill for the project your manager could lower his or her estimation of your abilities.

I suggest that you never refuse a project by citing that you think it's a bad idea. You haven't been asked for your opinion on the project; you've been charged with enacting it. Questioning its wisdom puts you in the worst possible light: you're not simply "refusing orders," you're exceeding your authority or responsibility in a way that your manager could feel is threatening. Instead, you need to either argue that you're not the right person for the job, or that you've got too much on your plate already.

Don't say you can't do a job. Instead, say you believe there's someone in the company who could do it better. Have a specific person in mind and cite a particular skill or ability. Similarly, don't say you don't have the time to tackle a job. Instead, say you need your manager's help in setting priorities for you since you're already working on so many other projects.

If your manager accepts your refusal, do your best to repair any self-inflicted damage by subtly emphasizing everything you are doing and will continue to be doing. If your manager insists on your taking this project on, don't continue to resist. Try to dilute the responsibility and workload somewhat by suggesting the formation of a committee or group to focus on the project.

The best time to have this discussion is early in the day, early in the workweek. If you can speak with your manager prior to normal business hours, that's best of all, since it will afford you undivided attention. (See Workscript 6.1.)

If one of your employees refuses a project you've assigned them, don't waste time trying to change their minds. Whether your employee's reasons are sound or not doesn't matter. The fact that he or she has decided to risk alienating you in this way, at a time when job security is nonexistent, proves they won't be able to do a good job. Consider any alternatives they suggest, but keep in mind these suggestions might be motivated by politics. There's no point engaging in criticism. Just thank the employee for being so honest. However, weigh their refusal and what you feel were their true motivations the next time you judge and rate their job performance.

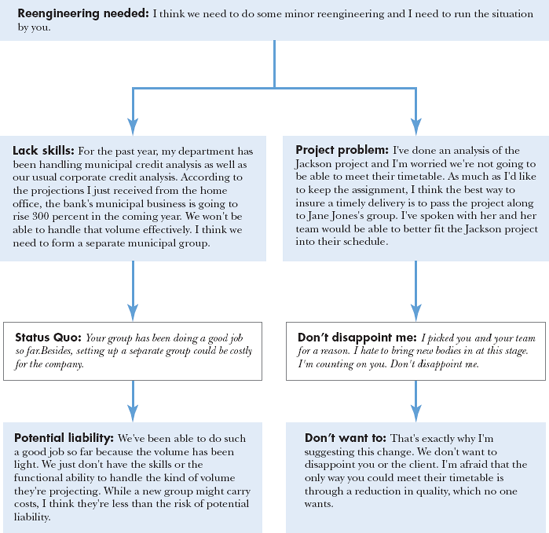

Trying to get released from a project which you've already commenced is riskier than refusing to take the assignment in the first place. That's because it can be perceived that you're admitting defeat. Unless handled adeptly, it can dramatically alter how you're perceived within the company.

The only way to minimize the potential harm is to frame this as an objective problem for the company. It's not that you don't have the time, it's that your department can't deliver the kind of quality job the company deserves in the time available. It's not that you don't have the ability to complete the task, it's that your department doesn't have the skills needed to deliver the kind of work the company expects.

Since any kind of change in midstream will result in some cost to the company, you need to stress that the costs of not making the change would actually be greater. Deflect personal attacks by affirming that you're putting the company's interests above your own. Prepare a memo outlining your argument, which you can present to your manager, but also which, more importantly, you can keep in your files in case you're not given relief and your fears are realized. That won't free you of some responsibility, but it will force your direct manager to share in any fallout.

Don't pursue this effort unless you're certain that the alternative—that is, staying with the project—will result in disaster. Your reputation and status will take at least a temporary hit from this, whether or not you succeed in getting relief. Your goal is to do your best to keep the damage from being permanent.

There's no good time to have this conversation. Don't delay or procrastinate. The sooner you have this dialogue, the sooner you'll recover from any damage. See Workscript 6.2.

If you're approached by an employee who wants relief from an active project or assignment, your only judgment should be who can replace them and how the change will be managed. In the current work environment, when someone comes to you and says they can't do the job, they're trying to avoid disaster, not maneuver politically. Relieve them, consider their suggestions about replacements, but make your own independent assessment.

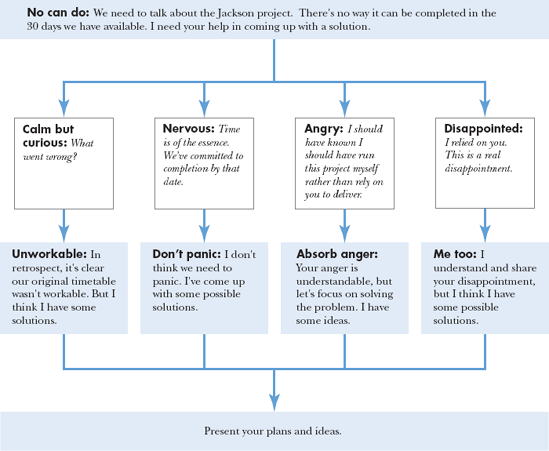

The secret to asking for a deadline extension is to make it clear that your only problem is time; nothing else is wrong. Rather than coming to your manager with an apology and a series of reasons for why you're not going to be able to meet the established deadline, steer the conversation as quickly as possible to the solutions. The past is past, the future result is still to be determined.

The mistakes were made in the original setting of the schedule, not in efforts made subsequently. Either the scope of the project or the difficulties were not fully understood early on. Now that the actual dimensions and elements of the project are clear, you can come up with a realistic, achievable deadline. Whatever the response, steer the conversation to your plan, which you'll deliver in writing as well as verbally.

There are always three general options available when deadlines are unachievable: get more time, hire more help, or submit a partial result on the date with the final product to follow later. Your plan should explore all three options but make the case for one in particular.

Have this conversation as soon as you realize you won't be able to meet the deadline. Procrastination will only make the situation worse and make you look less professional. See Workscript 6.3.

If an employee comes to you to ask for more time, you need to make a judgment as to which is the better outcome: lower quality, but on time; more costly, but on time; or high quality, but late. In today's workplace you have to assume that the deadline really is impossible to meet for the employee to have risked your wrath and potential repercussions. What you need to do is come down fully in favor of the deadline, the cost, or the quality. You don't want to provide something that's both lower in quality and late. Either make whatever compromises are required to meet the deadline, or get fully as much time as you will need to deliver the best possible result.

There are few more fearful workplace conversations than having to tell your superior that something has gone wrong. You're embarrassed and worried that this failure could impact your current job status and your future. That's why it's only natural, and quite common, to postpone, procrastinate, and do everything you can to avoid this dialogue. However, this normal reaction is actually the worst response you can have.

Your goal in this conversation is to fulfill your obligation of disclosure while minimizing the damage to your current and future employment. The best way to accomplish this is to turn the discussion away from the past—what happened—and toward the future—what do we do now? Your best hope of doing this is to ensure that you're the person breaking the bad news. That gives you the opportunity to put the event into context and present a plan that mitigates the damage to the company.

There's no need to burst into the boardroom during a meeting to deliver the bad news, but you do need to present it as soon as you have your reaction memo written. The need to be the one who breaks this news is more pressing than picking the right day of the week or time of the day.

If you bear some responsibility, own up to it immediately, and then pivot by taking responsibility for the reparation action as well. If the problem was beyond your control, point that out, but demonstrate that you are now back in control by presenting your planned response. Obviously, both of these tactics require you to have developed a plan prior to the meeting. Put it in writing so there's something tangible and positive for you and your superiors to focus on.

Absorb any anger or threats, realizing such feelings may be as much or more about the situation itself than about you. Keep doing whatever you can to steer the conversation toward solutions. See Workscript 6.4.

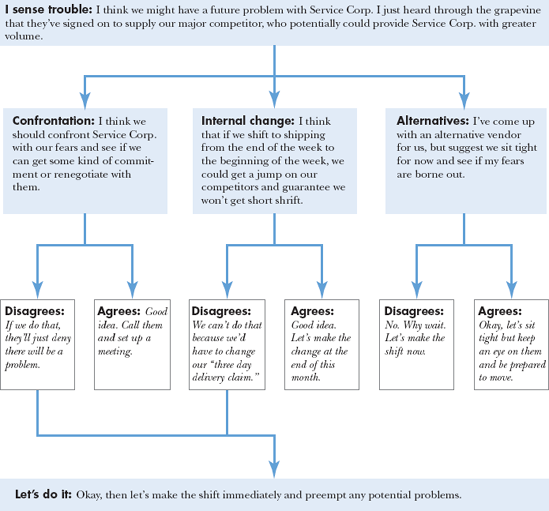

Warning your manager about potential rather than actual problems requires a careful balancing act. You need to provide as much advance warning as possible, but at the same time you need to have done sufficient investigation and preparation so the conversations go as well as possible. Wait too long and you appear as if you're not on top of the business. Send up the red flag too soon, and you can be perceived as the company Chicken Little. Give a warning without having a plan in place, and it looks like you're panicking. Craft too extensive a response plan, and it could seem like you've concealed the problem for some time. The key is to take just enough time to ensure there's evidence that your suspicions are more than just intuition, and then just enough time to come up with the outline of a plan.

Be cautious when delivering the news of a potential client or customer problem. The fear is that your manager will react poorly and "blame the messenger." The best way to avoid that is to assume as much control over the conversation as possible. Give your manager a chance to vent, but steer the discussion toward your possible solution and away from the causes. There will be a time for a postmortem, but now is the time for action. If you can subtly show that you're not to blame, that's fine, but don't veer toward pointing a finger. The more you can get your manager involved as part of the solution, the more he or she will focus on the future, not the past. See Workscript 6.5.

You'll have more room for preemptive action in dealing with potential vendor or supplier problems than you'll have in dealing with possible client issues. While you still want to bring this to your manager's attention as soon as possible, you should spend a bit more time planning out possible responses. That's because it may make sense to act immediately, rather than wait for your fears to be proven accurate. See Workscript 6.6.