With the workplace more unpredictable and chaotic than ever before, I believe there are no more important workplace conversations to master than those dealing with dramatic transitions, the announcements that explode like bombshells in the office.

You might think that in a time when terminations are so common, scripts dealing with those difficult conversations should take priority. While they do of necessity figure prominently in this book, I don't think they're the most important for one simple reason: they almost always represent a fait accompli—an irreversible action. As you'll read when I do cover these scenarios, there's no point trying to argue once a termination agreement has been reached. Energy should instead be directed toward mitigating the impact.

Workplace bombshells are so important because they represent the opposite of a foregone conclusion. The situation is in flux, nothing is established, so you have as much opportunity as you ever will in today's workplace to influence eventual outcomes. Sure, a new boss may already have a personnel plan in place, but since it hasn't yet been enacted you can give them reason to change it. Similarly, employees may have preconceived notions about what a new boss, a relocation, or a reorganization means for their futures, but you still have a chance to affect their reactions.

Whatever transition conversation you're facing, and whatever side you're on in the dialogue, it's important you take into account how the new workplace environment effects these situations.

First, personal rapport is much less important now than it was in previous years.

Experts, myself included, used to suggest that it was important to forge some kind of personal bond with your opposite numbers, not only to make transitional periods smoother, but also to form a warm human connection that could serve as the foundation of future relations. The hope was that managers would give more of a break to employees with whom they had warm relations, or that such a friendship could at least be used as leverage. Also, the thought was that if a new manager was perceived as kind and caring, it would minimize the number of employees who would reflexively jump ship.

Today, no degree of personal affinity makes any difference in managerial decisions; it's all about the money. And with the job market in such a poor state there's little fear of many people jumping ship. Instead, you may have to force people to walk the plank. Now, rather than personal rapport, it's professionalism that matters most. The model for these scenarios isn't people on a blind date, it's members of the military meeting to issue orders and give reports.

Second, spinning and effusiveness won't work. In fact, they're apt to backfire today.

Painting an optimistic picture of a situation—focusing on the glass being half-filled rather than half-empty—has long been a favored management tool for maintaining morale. And when employees still had some trust in management's pronouncements, and hoped for the best in every situation, spin could work. Employee effusiveness could be just as effective a device in years past. Managers always wanted to believe they had the support and goodwill and even admiration of their employees. When workers gushed about how much they loved the company and their jobs, managers tended to believe it and take it as a sign of their own effectiveness as bosses.

Today, spin actually decreases rather than increases discomfort during transitions. Employees are acutely attuned to the reality of their situations. What used to be characterized as a pessimistic attitude can now be viewed only as realism. Managers trying to gloss over reality will be viewed as outright liars, not merely as Pollyannas. Paint a glass as being half-full and employees will think it is almost completely empty. Employees who show excessive emotional commitment to either the company or their boss will be viewed not as enthusiastic supporters but as brown-nosing toadies, dishonest individuals not deserving of rudimentary respect. Effusiveness is likely to hurt rather than help your employment status. The best approaches today are simply to be honest and polite.

Finally, group discussions can now be more effective than one-on-one meetings.

For years it has been thought that meeting face to face with individuals, one at a time, was the best way for a manager to communicate with employees. It was thought to show respect, allow a greater degree of back and forth, and provide better outcomes to dialogues.

But now, the level of fear among employees is so high, and their trust in management is so low, that being singled out in any way at all is instantly perceived as being negative. Being called in to speak to the boss can only be bad. The best way to handle many transition conversations today is to hold them in a group setting. Being one of many gives some employees at least a minimal sense of security in a very insecure environment. And knowing that you are not being singled out in any way protects employee esteem and preserves whatever morale remains.

When the situation is reversed and you're one of the group with whom a transition is being discussed, resist the urge to speak out either to raise an objection, voice a concern, or even ask a question. Nothing good can come of you standing out in this kind of group situation. You'll only mark yourself as a troublemaker or potential problem. If you have an issue that you must address, do it later at a private meeting that you initiate.

To sum up, when dealing with transition conversations today, strive for maximum professionalism, be direct and honest, be polite rather than effusive, and hold group discussions rather than one-on-one conversations whenever possible.

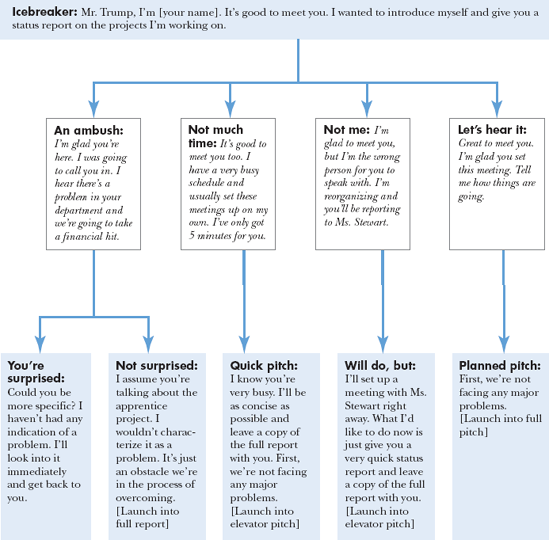

Your goal when meeting a new boss is to clearly demonstrate you're not a problem. You're a good soldier with a sense of urgency. You're smart, but not so smart as to possibly be construed as a "wise guy" or any kind of threat.

Initiate the meeting by setting up an appointment either directly with the new boss or through his assistant. If you're asked about the reason for the meeting, say you want to introduce yourself and provide a status report.

Prepare for the meeting by drafting a formal memo reporting on the status of all your projects, your staff, and your budget projections. Using this memo as your outline, prepare a complete oral presentation that covers all the points made in your memo. Then, when you have that presentation down pat, prepare a shorter "elevator" version of the presentation that lasts no more than three minutes.

In most cases you'll be leaving this memo behind after your meeting. But don't present it immediately unless you're told you will have only five minutes or you're meeting with the wrong person. If you are interrupted or cut short during your oral presentation, don't let the memo serve as a substitute. That would give your boss an excuse for not meeting with you again. The idea is that the memo should serve as a reinforcement or amplification of your pitch, not a replacement.

Dress the way you normally do at work, making sure there's nothing disconcerting about your appearance or hygiene. Avoid the temptation to scan the boss's office looking for cues and hints about him or her. Maintain eye contact except to consult your notes.

If you're told you have only a few minutes, launch into your "elevator" pitch and use your memo as a supplemental "leave behind." If you're told there will be a reorganization and you'll actually be reporting to someone else, don't characterize the shift in any way. Instead, explain you'll set up a meeting with your new boss as soon as possible, ask to provide a brief status report, give your "elevator" pitch, and leave your memo behind as a supplement.

If you're ambushed with a problem you're aware of, explain how the issue is an obstacle rather than a problem. This is more than a semantic dodge. It demonstrates that the issue is temporary and that a solution has already been found. If you're not aware of the problem, don't deny it. Explain that it's a surprise to you, that you'll investigate it further, and that you will get back as soon as possible.

Close your conversation with a simple thanks for the meeting and a polite, but not excessive, expression of best wishes. See Workscript 2.1.

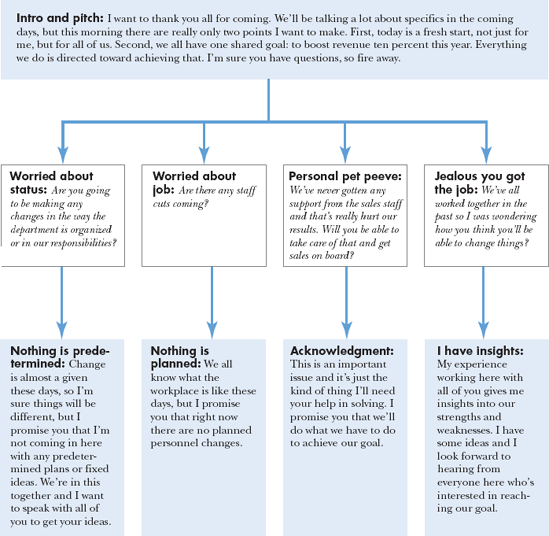

When you meet your direct "reports" for the first time, the most important thing you need to accomplish is to plant the seeds of future teamwork and community. That's true whether you're a complete outsider, or someone coming in from another part of the company, or you've been promoted to now lead your former peers.

An obvious way to signal the importance of teamwork is to make sure your first "meet and greet" is done in a group setting. Avoid preliminary one-on-one meetings if possible, to avoid sending a message that some are "insiders" or more important than others.

This group introduction should take place as early in the week and in the day as practical. That will let you issue marching orders that can be acted on immediately so the team is all pulling together from day one. End-of-week introductions could lead to weekend intrigue, gossip, and fear.

Pay careful attention to your garb. You want to give yourself the appearance of leadership, while not putting too much distance between yourself and the rest of the team. If you're coming in from outside, and are as a result largely uninformed about the staff, wear conservative, formal business attire. That means nothing flashy and no "bling." If you're coming in from another department or have been promoted from the ranks, simply turn your attire up one subtle notch of formality. For example, wear a suit if you usually dress in separates; don a jacket if previously you were always in shirtsleeves. You want everyone to know you're at a higher level, but you don't want to look like you just won the lottery or have forgotten your "roots."

It's essential you avoid spin and propaganda. Don't ignore the hard truths or explain them away. You can expect people to ask questions to which they already know the answers in an effort to test your honesty and directness. Saying there will be no changes is prima facie absurd; your simply being there is a change. These people haven't been living in a bunker for the past few years: they know how business works.

If personnel cuts have been planned prior to your arrival, vehemently push for them to be carried out before you take the helm. If you come in as the grim reaper, the impression will be permanent: You'll never win the existing staff over. You want to be the one who helps pick up the pieces and puts the team back together, rather than the one who tears the group apart.

Acknowledge whatever fears are expressed and demonstrate openness to even the most trivial, small-picture issues that are raised. Explain that the only stupid question is the one that goes unasked. You want everyone to feel that they are being heard and that you'll be open even to their particular, private concerns.

Stress that this is a new day, not only for you but for the whole team. The past is the past. From this moment you are all on the same path with the same goal. See Workscript 2.2.

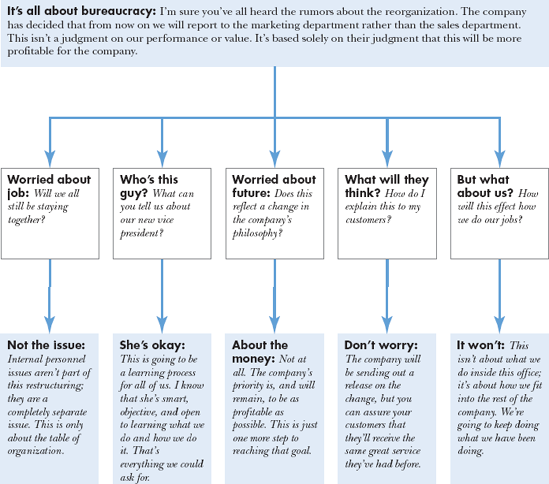

Whether your group has been incorporated into an entirely new division or now reports to a different executive team, the problem is the same: free-floating uncertainty. Today, even in the best of times, there's a constant low-grade uncertainty in the workplace. When a restructuring has been announced, those fears rise to the surface and threaten to dominate the workday. Your goal is to calm everyone, to the greatest extent possible, so that you can get on with business.

This is another discussion that should be held as a group. The specific day of the week and time of day matters less than that you have the meeting as soon as possible after the restructuring becomes common knowledge. If the word leaks out and the gossip starts, you may not even be able to wait for an official announcement. You want to calm your staff at the first sign of agitation.

The best way to do this is to be the ultimate source of rationality. Keep the issue in perspective. Report the facts honestly while reining in those who are jumping to conclusions. Explain that a restructuring is almost always done for organizational reasons and has nothing to do with personnel matters. That doesn't preclude future cutbacks, it just means the issues are separate.

Stress that you are all part of a team, and that you will still all be working together toward the same goals you'd had before the reorganization. Having everyone together, being honest and rational, and stressing continuity will mitigate fears and uncertainty. See Workscript 2.3.

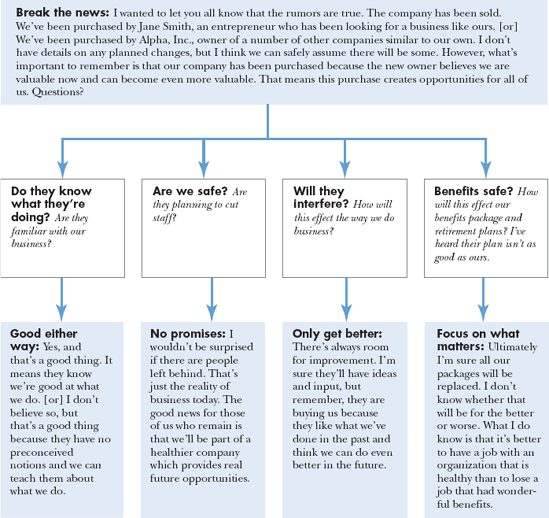

Other than imminent mass firings, or impending bankruptcy, the most stressful news employees can receive is that their employer has been purchased or is merging with another company.

Besides the normal fear of change, mergers or purchases by existing organizations carry with them the specter of wholesale changes. It's assumed, correctly, that widespread staff cuts often follow such a purchase. After all, one of the ways companies justify purchases is by calculating the economies of scale that could result. One combined sales team, for instance, is cheaper than two independent teams.

Even if the purchase is entrepreneurial, and represents only new management, changes are likely on the way. It's the rare individual who buys a new business and isn't tempted to put his or her mark on the company. That could mean something as benign as cosmetic change or as profound as a new approach to finances.

Ignoring or denying that changes, including possible staff or budget cuts, are likely, won't comfort your staff. It will only tar you as a dissembler, making them feel worse since now they'll feel like they're being led over the cliff by a liar.

What's needed is for you to frame what has happened as a generally positive sign. After all, a purchase or merger is a sign that the buyer values what is being bought. While short-term changes are likely, being valued by the new ownership means there's a long-term future for the organization.

This is another problematic discussion mitigated somewhat by a group setting. The more fears and concerns aired in this kind of controlled environment, the fewer whispered conversations will be held around the coffee pot.

If possible, hold this meeting after lunch, early in the week. Hold it in the morning and no work will get done the rest of the day. Hold it at the end of the week and imaginations will run wild over the weekend. Set aside as much time as necessary to answer any and all questions. Your goal is to provide accurate information in a realistic perspective to calm fears and minimize the time spent on the matter. See Workscript 2.4.

The most difficult business relocations are those that offer an employee no way to keep his or her job unless major life change is undertaken, such as moving to a new home and the uprooting of a spouse and/or school-age children that results.

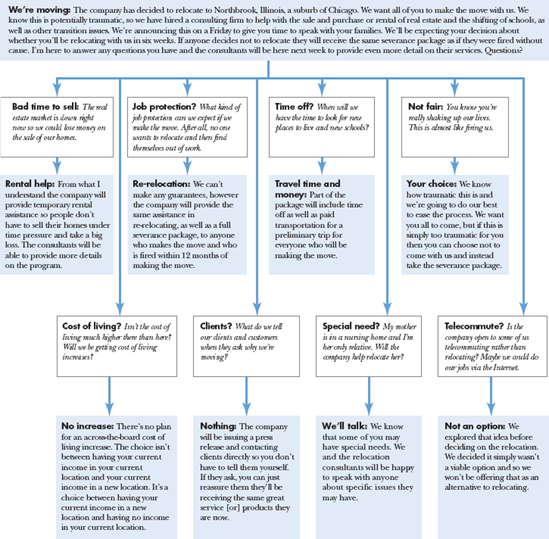

Typically, these relocations are done because a new owner or executive team demands it, or company strategists decide that a new location will provide a business advantage. The news is usually broken to the rank-and-file only after upper management has signed onto the move. It's vital that you stress that the company wants everyone to come along and sees them all as part of its future.

Losing the majority of existing staff and having to rehire new employees in a new location represents an extraordinary expense and disruption to operations. As a result, companies will provide considerable support, financial and otherwise, to help employees through the move. Help in the sale and purchase of real estate and in registering children in new schools are standard elements in these packages. Employees who choose not to relocate are almost always offered the same severance package they'd receive if they were fired without cause. Employees need to be given as much time as possible to decide if they want to make the move. Six weeks should be the minimum time period. Do your best to have the details of the entire support package before you announce the relocation.

It's vital that the announcement be made to everyone at the same time so there's no hint of favoritism. No one is going to be happy about this, but you want to minimize, to the greatest extent possible, all the inevitable gossiping and complaining. Do this after lunch on a Friday. That way you'll minimize the amount of work time devoted to griping while providing them with an immediate opportunity to discuss the matter with their family. This is, primarily, a personal decision. And as a result, it should be something they can immediately discuss with the family.

Stress your openness to fielding any question and in your responses make clear your honesty and openness. This is no time for spin or obfuscation. Be direct, honest, and rational. Make your case, lay out the facts, and let your employees decide for themselves. Don't try to minimize the impact of the relocation. Simply stress the opportunity it provides and lay out the details of the support the company is offering.

Your goal in this presentation is to minimize the reflexive anger over the move, stress the opportunities the shift offers, and provide all the details you can so your employees make an informed decision. See Workscript 2.5.