Chapter 1

You're Worth More Than You Think

Since you're reading this book, chances are that you can relate to my story in some way. Maybe you have what is considered a “good” job by most standards, yet you feel like you don't have much to show for it. Your net worth seems to be growing slowly, or not at all, and may even be negative … and to make matters worse, it's not like you hop out of bed in the morning skipping to work. Or maybe you love your career, but you can't figure out how to meet your financial goals. At times you may wonder, “What am I doing all this for? I imagined life to turn out a little differently than this.”

You're not alone. Nearly 70% of Americans don't like their jobs, according to a Gallup study,1 and 65% of Americans lose sleep over their financial worries, based on a CreditCards.com poll.2 Career and money woes appear to be especially prevalent among young professionals. In fact, a LinkedIn survey found that 75% of people in their 20s and 30s had experienced “insecurity and doubt” around work and money (no duh, right?) — or what they might call a “quarter-life crisis.”3

While many of us have tried to improve our careers and our finances, we may have done so by approaching them as two totally separate problems. But in reality, decisions you make in one of these areas can have a huge impact on all other areas of your life. When I came to this realization for myself, it totally changed how I thought about work and money, and how I chose to live my life.

Net Worth Is Not the Be-All and End-All

“You are not your job, you're not how much money you have in the bank. You are not the car you drive. You're not the contents of your wallet.”4

Yeah, that's a line from the movie Fight Club, but it's true: your net worth doesn't define who you are as a person or equate to your self-worth. Yet, early in my career, that's exactly what I thought. It was a pretty demoralizing mindset, especially when I stacked myself up against the billionaire corporate titans who graced the covers of Forbes and Fortune.

I was so focused on the dollars and cents (or lack thereof) that I neglected to account for everything else I had going for me. I was a young, college-educated professional with plenty of time to build my skills and earnings potential — my human capital. And according to the College Board, the value of your human capital can be significant, with average lifetime earnings for a college graduate estimated at nearly $1.2 million.5 Unfortunately, human capital isn't an asset that is typically accounted for in the calculations of a simple net-worth statement — but maybe it should be.

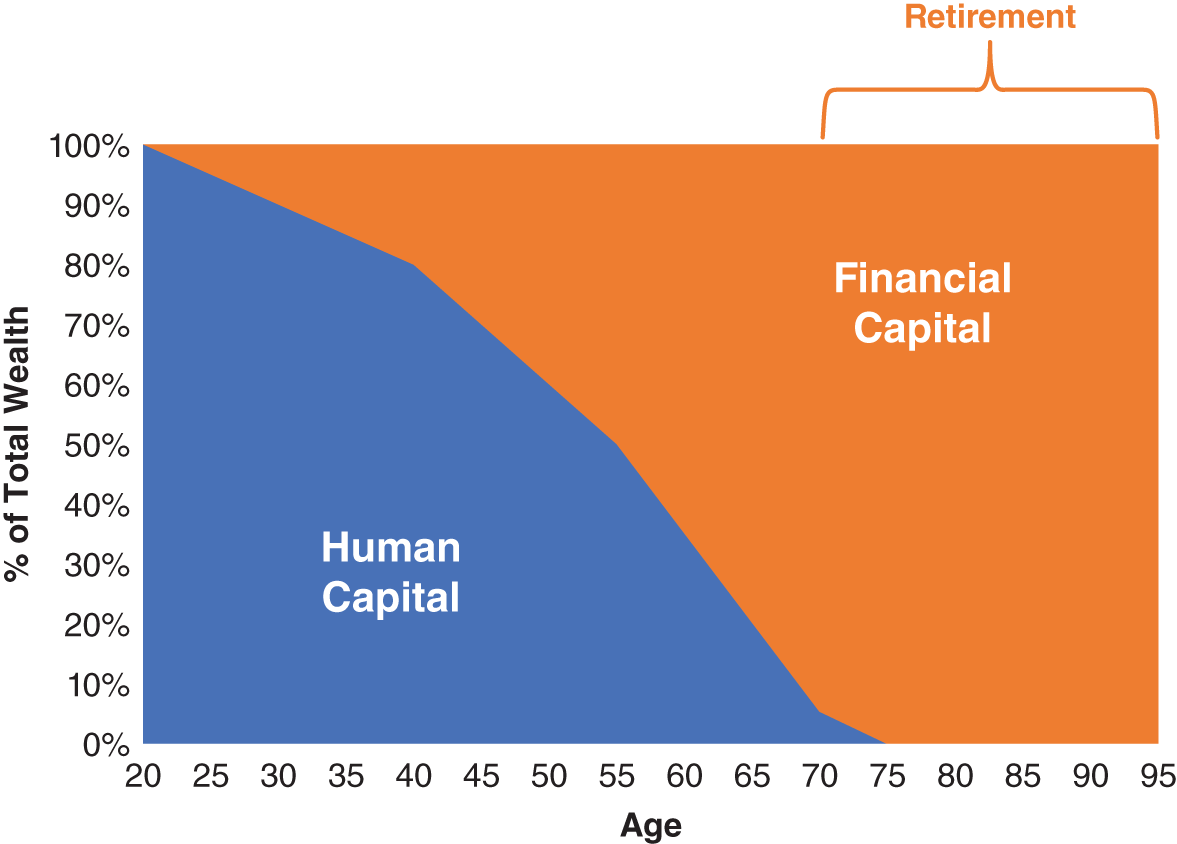

If you think about your total wealth as being made up of both your human and financial capital (Figure 1.1), it becomes clear how your work and money are connected, and why it's so important to find a job you like. In the beginning of our careers, our ability to work and earn income actually comprises the majority of our wealth. As we work, we begin to convert part of our earnings potential into real dollars, which allows us to fund our living expenses, save for our financial goals, and grow our financial net worth. During our prime working years, and especially early on, small improvements to our human capital, like building new skills or starting a side hustle, could have a much larger impact on our future net worth than trying to earn an extra 1% on our tiny investment portfolio.

Figure 1.1 The evolution of your human and financial capital.

Saving Money Is About More Than Just Retirement

Do you ever think about how bizarre the concept of saving for retirement is? After finally getting out of school, you enter the workforce raring to start a real job (or if nothing else, to be getting a paycheck), only to immediately be told that you should start socking away money for retirement — a point that feels like eons into the future when you're supposed to just play golf, volunteer, and sit on the beach. What the heck?

The reason this sequence of events may sound odd is because there's nothing logical about retiring. In fact, retirement as we know it didn't even exist until the late nineteenth century, when a politically savvy German chancellor invented the concept. For all of recorded history up until that point, you worked until you died — usually in labor-intensive jobs.6 Even when retirement programs did begin to gain popularity, workers couldn't begin collecting pensions until they were 65 or 70 years old. At the time, a lot of people died before they could even make it to retirement — and if they did make it, they often didn't get to enjoy it for long.

Fast forward to the present day, and it becomes clear that our attitudes about retirement haven't caught up with the times. The median retirement age in the United States today is 62,7 despite the fact that life expectancies have leapt to the 80s.8 Meanwhile, work has become much less physically taxing (gotta love the information superhighway!). While it would be tough for most 75-year-olds to toil at the steel mills all day, they might not find it so hard to consult for companies, write memos, or drive for Uber. And sure, playing golf and sitting on the beach sounds fun when you're working 60-hour weeks, but that could get old really quick (no pun intended).

Don't get me wrong — I do think saving for a potential retirement is important, but what if we could reframe our thinking about jobs, retirement, and this large financial goal? What if you could find a job that you loved doing, and that you didn't want to retire from? In that paradigm, you might still save money as early as possible in your career — but it wouldn't be solely to help fund your retirement. Instead, you could benefit from your good savings habits immediately by gaining greater flexibility to find a career you enjoy now, and even take some breaks along the way.

And get this: you don't need to amass a bajillion dollars before you can start doing this.

So, how much money do you need to gain more freedom and control over your life? That's your financial runway: the amount of savings needed to achieve your goals based on your specific situation, underlying expenses, and values.

How Long Is Your Runway?

A short financial runway is simply having an emergency fund — typically three to six months of living expenses saved in a checking or savings account. For example, if you spend $5,000 a month, you should build a target emergency fund of $15,000 to $30,000. Financial planners (myself included) usually recommend establishing an emergency fund as one of the first priorities for clients. This gives people a stash of money to tap in case something unexpected happens to them, whether that's losing your job, unforeseen healthcare expenses, or some other costly emergency.

A really long financial runway is sometimes referred to as financial independence — a concept that has become particularly popular among millennials through the Financial Independence, Retire Early movement (some use the acronym FIRE for short). Financial independence is typically defined as no longer needing to work for money because your savings and the income from your investment portfolio are sufficient to cover your living expenses. Many in the personal finance community use the 4% rule as a starting point to measure financial independence — a rule of thumb that says people need 25 times their annual expenses saved across cash and investments to reach financial independence. Building on our example above, if you spend $5,000 a month (or $60,000 a year), to be considered financially independent, you would need to have $1.5 million in cash and investments ($60,000 × 25).

Breaking Free: The Power of Financial Runway

Whether you're looking to make some big change or just a subtle mental shift, having financial runway can give you the confidence and funding needed to take action, so you can improve the immediate and long-term quality of your life.

Let's start with job satisfaction. Increasing your financial runway can positively impact your work situation by expanding the types of jobs you can pursue and by providing you the flexibility to take more professional risks. In practice, that could mean being able to accept a lower-paying but more fulfilling role that better aligns with your interests. Or it could mean feeling confident in changing industries, despite needing to work your way up all over again. Or maybe you're burned out from work and need to take a break — in which case, financial runway could allow you to take that unpaid leave and travel the world.

Kristin Wong, author of Get Money and contributor to the New York Times, realized the power of financial runway early in her career. After graduating from college, she landed a technical writer role in which she created content for product manuals — not exactly her dream job. After doing a number of side gigs, she realized she wanted to try her hand at screenwriting. To facilitate her job transition, Wong spent a year stockpiling six months of financial runway.

“If I hadn't saved up that money, I never would have been able to move to Los Angeles without a job,” Wong says. “It bought me the time I needed to land a writing job and pursue a career path that eventually led me to where I am now.”

On a subtler level, financial runway can help improve your day-to-day state of mind — often in small but meaningful ways. My client Morgan, for example, suffered from major burnout after working for a couple years as an associate at a large law firm because of her demanding colleagues, heavy workload, and incessant reactive requests. Although she wanted to do a good job, she felt trapped and bitter — that is, until she learned about the concept of financial runway.

When Morgan reached 12 months of financial runway, something interesting happened — she began to feel a sense of freedom. Having that much financial runway set aside allowed Morgan to walk into work every day knowing she was choosing to be there, rather than feeling like she was trapped and had no say in the matter. Going to work empowered and with a more positive mindset had other benefits as well; for example, Morgan found herself more receptive to feedback, more tolerant of difficult co-workers, and more patient about her career progression.

The subtle changes that result from having financial runway can also translate into more concrete and long-term benefits. If you approach your job from a positive mental state, you may produce higher-quality work and get along better with your co-workers. Ultimately, these improvements can make you more valuable to your employer, which could lead to promotions and a higher salary — enabling you to further build your financial runway so that you can continue making choices that align with your goals and values. That's what I'm talking about!

You Can Take Back Control of Your Life

Although it sounds counterintuitive, financial runway is primarily influenced by how much you spend, not by how much you make. Let that sit and marinate for a moment.

I always thought I needed to reach a certain income level or accumulate a massive amount of money before I could secure some buffer in my life. What I didn't realize was that controlling or decreasing my living expenses could actually make a large impact.

Consider two friends, John and Mark, who both make a gross salary of $150,000 and take home $100,000 after taxes. John has living expenses of $95,000 a year, while Mark lives on $60,000 a year.

By comparing their situations in Table 1.1, you can see how spending less allows you to:

- Save money faster: Because John spends most of his income, after a year of working, he isn't even able to save a month of financial runway. Meanwhile, Mark lives more frugally and saves eight months of financial runway over the same period of time.

- Reduce the cost of certain goals: Interestingly, because John's expenses are higher, he also has to save more money on an absolute basis to bankroll an emergency fund ($23,750 vs. $15,000) and his retirement ($2.375 million vs. $1.5 million). The combination of his high expenses and low savings rate means it will take him nearly five years to simply fund a minimum emergency fund (i.e., three months of living expenses), while it takes Mark just 4.5 months to fund his minimum emergency fund.

- Gain flexibility in job choices: John is pretty much locked into his current job or roles that pay a similar salary. His expenses are such that if he made less money, he would be running up significant credit card debt. Mark, on the other hand, has a fair amount of flexibility. If Mark received a job offer at a salary of $100,000, he could accept the position if he wanted because his living expenses are low.

Table 1.1 How Living Expenses Can Impact Your Career and Life Flexibility.

| John | Mark | |

| Gross Salary | $150,000 | $150,000 |

| Taxes | $50,000 | $50,000 |

| Net Pay | $100,000 | $100,000 |

| Expenses | $95,000 | $60,000 |

| Savings/Year | $5,000 | $40,000 |

| Financial Runway/Year | 0.63 Months | 8 Months |

| Emergency Fund Needed | $23,750 | $15,000 |

| Time to Fund Emergency Fund | 57 Months | 4.5 Months |

| Retirement Savings Needed | $2,375,000 | $1,500,000 |

| Minimum Salary Needed | $150,000 | $90,000 |

The bottom line is, your expenses have a huge impact on the amount of flexibility you can have, the cost of your financial goals, and the types of jobs you can take.

You Don't Need to Be Financially Independent to Have Financial Flexibility

Take a moment to think about your career, finances, and overall life. What type of pain points do you deal with on a daily basis? How would you feel if you could eliminate these frictions from your life? How much financial runway would you need to be able to do so?

Regardless of how you answered those questions, I have some good news: you likely don't need to be financially independent to have flexibility or freedom to change your career and life for the better. In fact, the amount of financial runway you'll need could be as little as a three-month emergency fund. The exact number will depend on the nature of the personal or professional change you're looking to make, whether you have a partner or parent who can help bridge the gap in living expenses (if necessary), and your own personal risk tolerance.

The first step toward determining the amount of financial runway you need is to gauge your current job and financial situation, which you'll be doing in Part 2. Then, you'll complete a series of exercises to identify attributes of your ideal career path. The more dissimilar your current and target jobs are, the larger your financial cushion will likely need to be to facilitate a switch. If you can continue to work in your current job and build the skills or experience needed to pivot to your ideal role, you may need less financial runway.

Your Ideal Career Is Within Reach

I hope that the concepts we've covered in this chapter have convinced you that you're worth more than a simple net worth statement. Regardless of your particular situation, the combined effect of your human capital and your ability to build financial runway means that real change is possible in your career — even if you're starting with a negative net worth and have loads of student loans to pay off.

In the next chapter, we'll take a deep dive into understanding why so many of us feel trapped in our jobs despite being able to tap our human capital and financial runway. I'll challenge you to reconsider certain beliefs that you may have subconsciously internalized, allowing you to move toward the career you want instead of a path that society has laid out for you.

Notes

- 1. Anna Robaton, “Why So Many Americans Hate Their Jobs,” CBS News, March 31, 2017,

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/why-so-many-americans-hate-their-jobs/ - 2. Jean Chatzky, “65 Percent of Americans Are Losing Sleep Over Money. Here's How to Change it,” NBC News, December 19, 2017,

https://www.nbcnews.com/better/business/65-percent-americans-are-losing-sleep-over-money-here-s-ncna831096 - 3. Blair Decembrele, “Encountering a Quarter-life Crisis? You're Not Alone…,” LinkedIn Official Blog, November 15, 2017,

https://blog.linkedin.com/2017/november/15/encountering-a-quarter-life-crisis-you-are-not-alone - 4. Fight Club, film, directed by David Fincher, performed by Brad Pitt, Fox 2000 Pictures, Regency Enterprises, Linson Films, Atman Entertainment, Knickerbocker Films, Taurus Film, 1999.

- 5. Jennifer Ma, Matea Pender, and Meredith Welch, “Education Pays 2016: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society,” College Board, 2016,

https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/education-pays-2016-full-report.pdf - 6. Seattle Times staff, “A Brief History of Retirement: It's a Modern Idea,” Seattle Times, December 31, 2013,

https://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/a-brief-history-of-retirement-its-a-modern-idea/ - 7. “2019 Retirement Confidence Survey Summary Report,” Employee Benefit Research Institute and Greenwald & Associates, April 23, 2019,

https://www.ebri.org/docs/default-source/rcs/2019-rcs/2019-rcs-short-report.pdf - 8. “Life Expectancy at Birth, Female (Years) – United States,” World Bank,

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.FE.IN?locations=US - 9. William P. Bengen, “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data,” Journal of Financial Planning, October 1994,

https://www.onefpa.org/journal/Documents/The%20Best%20of%2025%20Years%20Determining%20Withdrawal%20Rates%20Using%20Historical%20Data.pdf - 10. Philip L. Cooley, Carl M. Hubbard, and Daniel T. Waltz, “Choosing a Withdrawal Rate That Is Sustainable,” AAII Journal, February 1998,

https://www.aaii.com/journal/article/retirement-savings-choosing-a-withdrawal-rate-that-is-sustainable