Chapter 9

High‐Performance Training for Parents: Y.O.D.A. for Teens

Being a young person in today's day and age is as stressful and challenging as almost any time in recent history. Navigating the social landscape in the context of COVID‐19, surging hormones, cognitive impulsivity, and self‐conscious developmental awkwardness clearly presents an exceedingly slippery slope for parents of teens.

When we factor in the ubiquitous and addictive nature of screens and social media, as habit forming as illicit drugs or gambling, the constant uploading of anxiety‐provoking messages related to social inclusion and perfection, combined with verbal and nonverbal messages from parents and teachers related to high performance and achievement, it's clear that this is not a recipe for sustained healthy adolescent development!

What's also clear is that protecting our children's mental health and mind‐body well‐being by strengthening their Y.O.D.A. has never been more important than it is today.

Parenting during adolescence requires a markedly different skill set than that required during the early years of development. Your teen is well past the high chair, rapidly growing into their independence, expressing their individuality in unique and colorful ways. They are now fully verbal and using their language skills in ways that at times feel like a blessing and others like a curse.

This brand‐new communication landscape for parents and teens is laden with joy and angst, productivity and pitfalls, celebrated achievements and sheer unadulterated frustration. As emotional hormone‐driven rollercoasters of uncontrollable highs and lows, teens are doing exactly what they're supposed to at this age and stage. Adolescence is the age where, if development is following a typical course, they challenge the status quo, push the boundaries, and begin the journey of discovering who they are now and who they want to be in life.

It's important to note that teenage developmental chaos is not all bad. In this churn of self‐discovery, brain development, and biologic recalibration lies a massive opportunity for learning, growth, innovation, and expression of remarkable human potential. The following excerpt from Robert Sapolsky's excellent book Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, from the chapter titled “Adolescence; or, Dude, Where's My Frontal Cortex?” captures adolescence brilliantly:

Does this description resonate with parents of teens? Typical hallmarks of the adolescent years are impulsivity, defensiveness, moodiness, intransigence, and poor judgment, driven largely by the developmental disconnect between the neural networks that shape social‐emotional behavior and those that underpin rational, higher‐order, integrated thinking.

As covered in the Chapter 8, humans develop social skills first for evolutionary purposes (survival), while the neural pathways for attention, emotion regulation, and executive function develop much later. Executive function, abstract thinking, and reasoning capabilities unfold across life, though in a more significant way through our late 20s and early 30s. Our brains are continually growing and evolving, creating new neural connections based on life experiences and atrophying those we no longer need or use. (See Figure 9.1.) This epigenetic remodeling, called “neuroplasticity,” is an ongoing process throughout life, markedly more rapid during the earlier stages (childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood) relative to middle age and elderhood.

Figure 9.1 Neuroplasticity unfolds rapidly earlier in life.

Similar to early infancy and childhood, the teen years are a known “sensitive period” where the brain is the most highly malleable and open to new habit formation than at any other time across life. This means that adolescence is a potential high‐return‐on‐investment (ROI) developmental window when new learning has much greater odds for lifelong uploading into your teen's long‐term memory, where it sticks for good. That is, if the message can get through to their inner command center!

While inputs into the recipe for your teen's long‐term healthy development are vast and extensive, by far the most important ingredients for ensuring long‐term success will come from you. It is you who have the unique and priceless opportunity to shape their habits, beliefs, and behaviors during a developmental period of time that is unlike all others.

By living your message and modeling good judgment, particularly in times laden with stress or conflict, and by practicing disciplined self‐care to sustain balanced mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual health, you can begin to steadily embed a trusted and reliable inner coach that can protect them from the downside of life‐altering bad decisions.

Rising up into the reflective consciousness of Y.O.D.A. is the first necessary step in transporting you knowingly above the complexities of a situation brewing on the ground. And it's only from this higher‐level vantage point that we can see what's really happening. When we're not enmeshed in the heated emotions of the moment, insights can begin to surface, observations that empower you to see that the spirited pushback from your teen is not personal. Rather, they are testing the boundaries you've established, something that is completely in line with their healthy growth and development.

Reframing teen intransigence that appears to be an all‐out affront of willful disrespect and disregard, and doing this at a powerful teachable moment, can, if managed correctly, embed a sticky life‐changing lesson, and not despite the emotional charge of the moment, but rather because of it. All meaningful learning involves emotion, and we are much likelier to remember events that have significant emotional valence. And when your wise and skillful Y.O.D.A. situation management deescalates a moment that could easily have felt doused with emotional kerosene, all of a sudden this moment becomes a shared experience of learning and growth, where both you and your child can see each other as human beings and can begin to chart a healthy course forward.

A simple reflective pause, one that brings you calmness and perspective in a meta‐moment, can change everything for you and for your ornery teen. Modeling Y.O.D.A. in a heated moment is, bar none, the most powerful way you can teach them how to thoughtfully and skillfully manage their own difficult, emotionally charged life situations in the future. A gift of epic proportions!

Your refusal to become defensive and attacking, and your willingness to listen and stay positively engaged, will unknowingly be uploaded into their repository of Y.O.D.A. learning. The gate to your teen's inner command center will likely open because they know, deep inside, you love them and always have their best interests at heart. As should be obvious by this point, we most effectively convey important lessons not by harsh, heavy‐handed punitive messaging but rather by subtly sliding in lessons below the radar of conscious awareness, not only by what we say but how we say it. It is our being what we want them to be that carries the most powerful Y.O.D.A. message and lesson.

Wise Decision Insight: All emotionally charged challenges in life, particularly the painful ones, represent fertile ground for Y.O.D.A. learning in the areas of emotional control, perspective, and sound judgment.

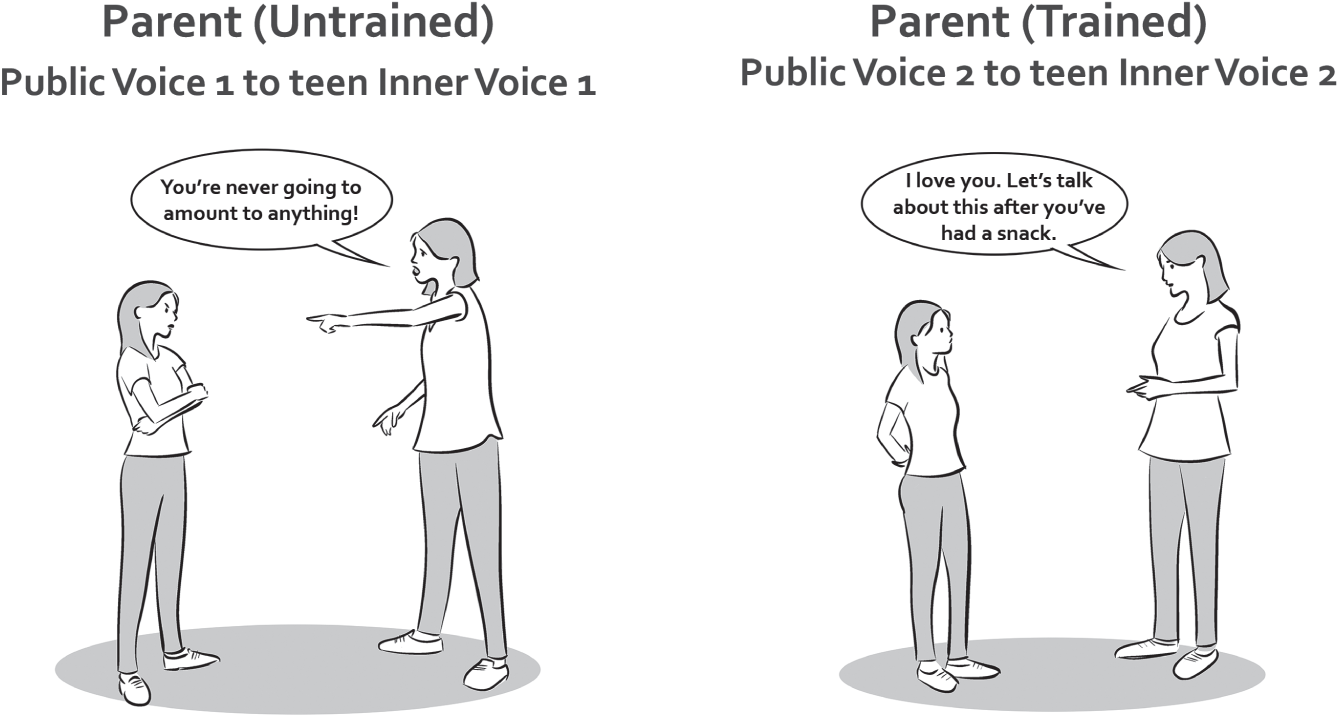

In summary, as the primary adult in your teen's life, your words and tone matter more in terms of long‐term health and development than most people ever suspected. The old adage “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” is diametrically opposed to cutting‐edge research on the impact of repeated hurtful language, particularly in the case of young children. (See Figure 9.2.)

It's important to understand that neuroscience research has demonstrated that the brain interprets emotional pain as equivalent to physical pain. This finding has broad ramifications for us as parents in our efforts to safeguard the spiritual, mental, emotional, and physical well‐being of our children and massive implications for the mental health crisis in our country and world. As you learned in Chapter 7, what's real in the mind is also real in the body at a molecular level, and this is a central tenet that we must all understand and hold close. Optimal mind‐body health requires disciplined and diligent self‐care, which is the foundation for wise decision‐making and all else in life.

Figure 9.2 Contrary to the old saying, words can have a powerful impact.

Time for Reflection and Y.O.D.A. Goal‐Setting

Here are a few exercises designed to help build the awareness and skills required to leverage teachable moments effectively with your teen, particularly the emotionally charged, stressful situations that seemingly spring up out of nowhere, impacting both your mood and that of your child and infusing negative energy into the home.

Reflect on the following questions for you and your teen. If you have more than one child, please reflect on each one individually. Remember, we humans are like snowflakes: No two are exactly alike, not even identical twins!

- Write down two of the most significant areas of difficulty with your teen (e.g. technology use, cleaning up after themselves, homework).

-

- Write down two or three major areas in your home where difficult conversations about these topics tend to occur (e.g. kitchen, bedroom, television area), and consider the times of day when conflict is likeliest to arise (e.g. dinner time).

-

- Name one situation between you and your teen over the past week that entailed a hot‐button topic. How did you handle it, and was the situation resolved? Was there any forward movement? How did your teen respond, and how did you feel afterward?

Success for All: Engaging Y.O.D.A.

Being aware of the major hot‐button topics and both when as well as under what circumstances they're likely to occur is step 1. Advance preparation is key! Knowing your major learning and teaching goals will help you stay alert for meta‐moments, connecting the dots of opportunity when the moment is upon you, vastly improving your odds of success.

Now let's visualize, reflect, and write. In the blank space below, recast the story of the challenging parent‐teen interaction with your Y.O.D.A. in charge and in high gear, listing the time, topic, situation, and physical location, seeing and feeling the 360‐degree picture of the event before it unfolds. You are the leader, the agent of change, embodying wisdom in action, making thoughtful, wise, and balanced decisions that guide you and your teen to a constructive long‐term outcome.

This vision is indeed possible with Y.O.D.A. practice. And if you need motivation to double down on building those neural pathways, here it is. By the time your teen graduates from high school, it's estimated that 93% of the time you'll ever spend with them across their entire life is now in the rearview mirror. It is a sobering statistic, but think about it: Once they go off to college, get their first jobs, and eventually have families of their own, your opportunity to strengthen their Y.O.D.A. and decision‐making skills is vastly reduced.

So let's double down on your Y.O.D.A. training game plan to move toward the healthy, happy, connected, and loving relationship you aspire to with your teenager. While bumpy at times, the mutual respect and the knowledge that together you will find a way are hallmarks of this new way of being human together.

By showing up as your own Y.O.D.A. Best Self, you are actively and intentionally uploading decision‐making expertise not only to your teen, but throughout your entire family, given the ripple effect of emotions. You are seamlessly embedding the priceless gift of wisdom into the command center of your most precious asset, your child, a leader in the rising generation and the steward of your family legacy. It is a gift they are sure to pay forward.

Sources

- Casey, B. J., R. M. Jones, and T. A. Hare. “The Adolescent Brain.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1124 (2008): 111–126.

- Chein, J., D. Albert, L. O'Brien, K. Uckert, and L. Steinberg. “Peers Increase Adolescent Risk Taking by Enhancing Activity in the Brain's Reward Circuitry.” Developmental Science 14, no. 2 (2011): F1–F10.

- Covey, S. The 6 Most Important Decisions You'll Ever Make: A Guide for Teens. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

- Harris, J. R. The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do. New York: Free Press, 2009.

- Hetherington, E. M., R. M. Lerner, M. Perlmutter, and Social Science Research Council (U.S.). Child Development in Life‐Span Perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988.

- Hochberg, Z. E., and M. Konner. “Emerging Adulthood, a Pre‐Adult Life‐History Stage.” Frontiers in Endocrinology (Lausanne) 10 (2019): 918.

- Immordino‐Yang, M. H., and D. R. Knecht. “Building Meaning Builds Teens’ Brains.” ASCD 77, no. 8 (2020).

- Kreppner, K., and R. M. Lerner. Family Systems and Life‐Span Development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1989.

- Kross, E., M. G. Berman, W. Mischel, E. E. Smith, and T. D. Wager. “Social Rejection Shares Somatosensory Representations with Physical Pain.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, no. 15 (2011): 6270–6275.

- Larsen, B., and B. Luna. “Adolescence as a Neurobiological Critical Period for the Development of Higher‐Order Cognition.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 94 (2018): 179–195.

- Lerner, R. M. The Developmental Science of Adolescence: History through Autobiography. New York: Psychology Press, 2014.

- Lerner, R. M., and L. E. Hess. The Development of Personality, Self, and Ego in Adolescence. Vol. 3. Adolescence: Development, Diversity, and Context. New York: Garland, 1999.

- Lerner, R. M., and J. Jovanovic. Cognitive and Moral Development and Academic Achievement in Adolescence. Vol. 2. Adolescence: Development, Diversity, and Context. New York: Garland, 1999.

- Lerner, R. M., and L. D. Steinberg. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2004.

- Malin, H., I. Liauw, and W. Damon. “Purpose and Character Development in Early Adolescence.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46, no. 6 (2017): 1200–1215.

- Romeo, R. D. “The Teenage Brain: The Stress Response and the Adolescent Brain.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 22, no. 2 (2013): 140–145.

- Saxbe, D., L. Del Piero, M. H. Immordino‐Yang, J. Kaplan, and G. Margolin. “Neural Correlates of Adolescents’ Viewing of Parents’ and Peers’ Emotions: Associations with Risk‐Taking Behavior and Risky Peer Affiliations.” Social Neuroscience 10, no. 6 (2015): 592–604.

- Silbereisen, R. K., and R. M. Lerner. Approaches to Positive Youth Development. Los Angeles: Sage, 2007.

- Steinberg, L. D. Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence. Boston: Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014.

- Steinberg, L. D. Adolescence, 12th ed. New York: McGraw‐Hill Education, 2020.

- Stixrud, W., and N. Johnson. The Self‐Driven Child: The Science and Sense of Giving Your Kids More Control over Their Lives. New York: Viking Penguin, 2019.

- Stixrud, W. R., and N. Johnson. What Do You Say?: How to Talk with Kids to Build Motivation, Stress Tolerance, and a Happy Home. New York: Viking, 2021.

- Urban, T. “The Tail End,” Wait but Why, December 11, 2015. https://waitbutwhy.com/2015/12/the-tail-end.html