Chapter 8

Y.O.D.A. Rising: Parenting Young Children

I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

—Maya Angelou

Now that you understand the power of your inner voice, let's explore the most significant idea of all: how your public voice as a parent becomes the inner voice of your child, shaping the broad underlying themes of how they feel about themselves and the choices they make.

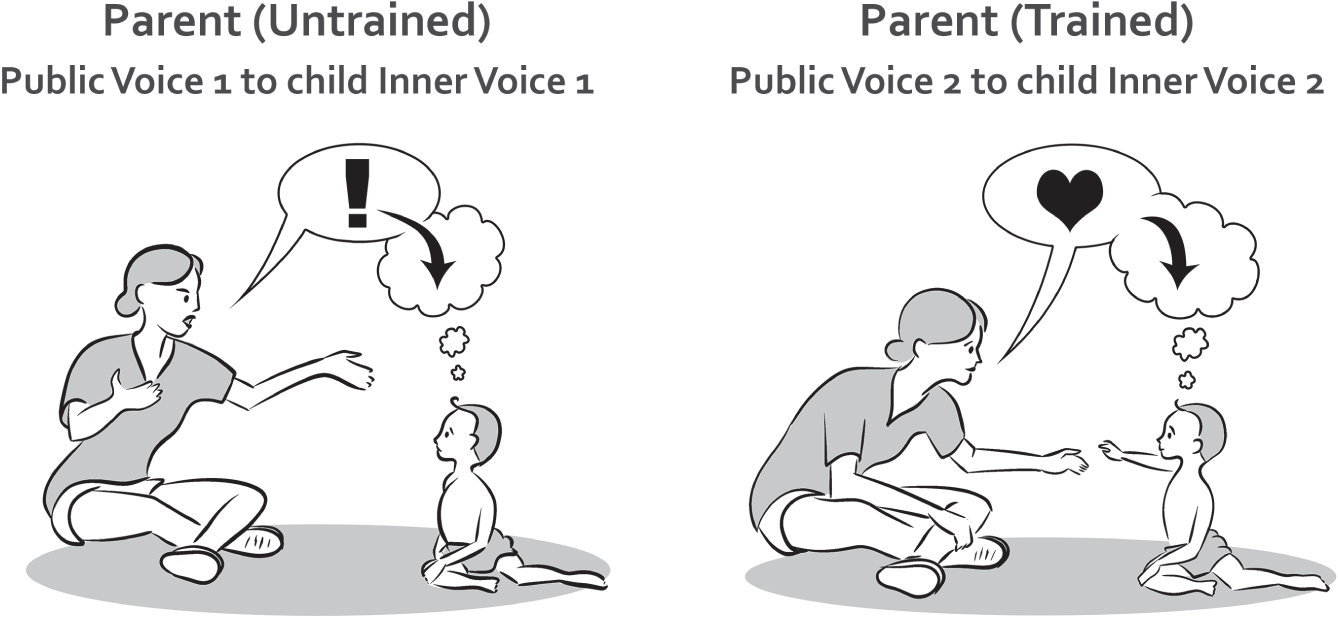

To understand how stories and belief systems cross generations, we will start by reflecting on the genesis of your own untrained Inner Voice 1 and how that voice may be influencing the public voice you use with your child now. More importantly, we will explore how your untrained public voice can be intentionally transformed into a trusted inner coach for your child that will yield priceless decision‐making dividends for life. (See Figure 8.1.)

As a parent, you are your child's first and most powerful teacher, and just as teachers require formal training in order to provide high‐quality lessons to their students, so do parents, particularly if a healthy inner voice was not embedded in you as a growing child.

Wise Decision Insight: One of the greatest gifts you can give to your children is a strong and wise inner voice, a measured and thoughtful decision advisor that will be with them throughout their lifetime, something we refer to as Y.O.D.A. Rising.

The parent‐child bond is unlike any other relationship in nature. Implicit trust and complete dependence are central to caregiver‐infant attachment relationships, not only for a child's healthy development, but for their very survival. It is within the context of this powerful bond that the primary caregiver's words, tone, behavior, and other nonverbal messages set the stage for what will become their fundamental belief systems, habits and behaviors, and competence in decision‐making.

Figure 8.1 Transforming the inner voice.

The infant brain is a rapidly growing learning machine, one that is built gradually over many years in a dynamic ongoing epigenetic construction process that begins at conception. Simpler neural connections form first, the ones that undergird the communication pathways in the brain for attachment relationships with the primary caregiver, for love, care, feeding, protection, and survival. More complex connections and networks, as well as the crosstalk connectivity between networks, develop later in time for other developmentally important activities such as talking, walking, socializing, reading, writing, and riding a bicycle. The human infant's brain is establishing more than one million new neural connections every second, with the highest priority given to those that increase the child's chances of thriving and survival.

As will be explained more thoroughly in Chapter 11, the things we invest our energy in by paying attention, particularly the things we focus on intently, grow stronger over time. As the primary caregiver, you are the center of the infant's universe, and hence you decide, by your energy investments, the qualities you wish to grow in your child and when.

Giving your attention and energy to love, appreciation, patience, empathy, compassion, kindness, and joy spawns growth and accelerated development in those priceless human capacities. It is under this evolutionary model that caregiver energy investments, evidenced in their stories and embodied in their actions, directly and unquestioningly embed emotions and behaviors that the child automatically emulates, all of which occur under the radar of the child's conscious awareness.

This is nature's way of equipping babies with the emotional tools, cognitive knowledge, and decision‐making skills required to survive and thrive later as adults. In the early stages of development, intentional discernment of what and who gains entry into their inner command center is simply not an option for the child. Information taken in from the outside world, in particular from the child's primary caregiver, is like an IV drip directly into the child's brain, as referenced in Chapter 6, programming early neural pathways that form the foundation for all later learning.

All information that passes through the infant's senses (hearing, vision, touch, taste, smell) in their experience of daily life creates and fortifies the neural pathways that become, for that particular individual, communication signals in the brain that represent de facto truth. The more energy that is invested by the mother or father in particular inputs to his or her child, like a loving smile, a warm cuddle, or rapid response to the child's needs, this “serve and return” dynamic of reliable connection fortifies these neural pathways into automated belief systems (I am safe, and I bring my mother and father joy). This felt sense of being lovable and valuable seamlessly becomes the underlying template for a critical inner belief that sits at the very center of our being, across life, as humans.

Just as the city of Rome was built atop a foundation developed centuries ago, the brain builds new learning on top of old, integrating novel information into an existing set of core beliefs. This highly apropos metaphor from neuroscientist David Eagleman is precisely why getting the child's foundation right in the early years is so crucial.

In this context, it's vital to know that the child's memory is not only stored in the structures and networks of the brain, but also throughout the body's viscera, organ systems, and muscles in the form of emotions and sensory information. Your words, and perhaps even more importantly your tone, the soft, high‐pitched voice in which mothers speak with their infants—a special language called “motherese”—will be remembered throughout the body, a felt sense of that particular moment in time. Your child remembers, at a subconscious level, the feeling of what it felt like to be in your presence, the most enduring and important recollection of all, persisting long after the concrete memory of your spoken words have faded. (See Figure 8.2.)

Let's pause now for a moment of self‐reflection to explore how our own inner voice may have been shaped by implicit and explicit memories of our early childhood via our parent's untrained Public Voice 1. Let's also examine how our command center may benefit from reevaluation to ensure the inner decision‐making capacity we are building in our children contains the wisdom of a trusted coach rather than the criticism of an unreliable and critical adversary.

To explore this multigenerational transmission of powerful unquestioned messages early in life, let's go through a reflection exercise and consider a few pertinent questions to ponder and process:

- How did your parent's public voice shape your inner voice as a child?

- Name two important positive messages repeatedly conveyed by the parent or the adult who raised you in infancy and early childhood (your primary caregiver). How did this data shape your beliefs about the world, your place within it, and your sense of competence, confidence, and self‐worth?

Figure 8.2 Tone of voice can convey more than words.

-

- What are two important negative messages from your primary caregiver that shaped your beliefs about the world, your place within it, and your sense of competence, confidence, loveability, and self‐worth?

-

- If you had to name one key positive message that helped you in your life, and one key negative message that hindered you, what would they be?

- Helped: _______________________________

- Hindered: _______________________________

- As you reflect on these deeply felt messages that shaped your life in powerful ways, which are the ones you do want to build and reinforce in your one child's command center? Which are the messages you do not want to upload?

- Yes, Upload! _______________________________

- Do Not Upload: _______________________________

It is by bringing discipline to your energy investments, by intentionally uploading helpful messages and choosing not to invest your energy in harmful ones, that you can break dysfunctional multigenerational family cycles and initiate a new positive narrative—the story you want yourself and your child to live their way into. With your trained public voice giving rise to a constructive, healthy inner voice, your child's decision‐making competencies and skills will be a fundamental part of how they operate in their world—across life.

Let's expand on this reflection exercise by turning to the present day, taking time now to explore key messages and themes you're uploading into your child's highly sensitive, rapidly growing inner command center.

- Name two important positive messages repeatedly conveyed by the parent or the adult who raised you in infancy and early childhood (your primary caregiver). How did this data shape your beliefs about the world, your place within it, and your sense of competence, confidence, and self‐worth?

- How is your present public voice shaping your child's inner voice?

- List two key messages you are uploading to your child's private inner voice via your public voice. Distinguish between times when you are relaxed and rested, and the emotional climate is stress‐free. Conversely, think of the times of exhaustion, household disorder, and crying infants or toddler tantrums.

- Stress‐Free Emotional Climate:

- 1: _______________________________

- 2: _______________________________

- Stressful Emotional Climate:

- 1: _______________________________

- 2: _______________________________

- How are the messages you're embedding into your child's command center similar to or different from the ones your parents uploaded to you?

- Similar: _______________________________

- Different: _______________________________

- Which of these messages are constructive and which are not? What messages do you intend to continue to upload and which messages do you want to be certain not to upload to your child?

- Now that you've reflected upon these high‐level multigenerational messages and patterns, let's do some parent‐child Y.O.D.A. training. Rising above in the moment from your raw, untrained Public Voice 1 to your best Public Voice 2, especially during times of stress, requires intentional and dedicated practice. For example, being aware of the reality of the moment, such as when your overly tired rascal toddler decides to throw their food all over the kitchen—food you've lovingly prepared for them—and embracing the opportunity this situation affords requires presence, insight, and practice. Your response, whether action or reaction, can upload a strength‐building inner coach to your child or a critical inner voice. This is a choice you will have. How should you respond?

- Write about a real‐life example from the past week in which you've lost your temper in a stressful moment with your child, one in which you wished you'd chosen to handle the situation differently. Which specific words did you use, and in what tone? What message did your body language communicate?

- Now write about the same event and how the scenario would have played out had you used your trained Y.O.D.A. to rise above the frustrating details of the moment, choosing to show up as your Best Self. What specific words would you use, and in what tone? What message would your body language communicate?

- Write about a real‐life example from the past week in which you've lost your temper in a stressful moment with your child, one in which you wished you'd chosen to handle the situation differently. Which specific words did you use, and in what tone? What message did your body language communicate?

- Finally, consider three key messages you intend to upload into your child's central command center (their inner voice) that you hope will accompany them as priceless assets in their future decision‐making and sense of self‐worth.

-

To recap: Children develop as they do in response to complex environmental inputs, nurture shaping nature all the way along, the full impact of which cannot be wholly known until much later in life, when they are well into adulthood. Those who are closest to the child, those who are in the best position to control what gets uploaded into their command center, have the greatest opportunity to powerfully shape the multidimensional health, happiness, character, and inner wisdom of the child, giving them the best possible odds of expressing their full human potential in their life.

Bottom line: A healthy multigenerational family story begins with an intentionally trained you.

Sources

- Cantor, P., R. M. Lerner, K. Pittman, P. A. Chase, and N. Gomperts. In Preparation. Whole‐Child Development and Thriving: A Dynamic Systems Approach. NY: Cambridge University Press.

- “Early Life Brain Architecture.” Harvard Center on the Developing Child, 2021. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/brain-architecture/

- Eagleman, D. The Brain. New York: Pantheon Books, 2015.

- Frith, C. “Role of Facial Expressions in Social Interactions.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364, no. 1535 (2009): 3453–3458.

- Gopnik, A., A. N. Meltzoff, and P. K. Kuhl. The Scientist in the Crib: Minds, Brains, and How Children Learn. New York: William Morrow, 1999.

- Hetherington, E. M., R. M. Lerner, M. Perlmutter, and Social Science Research Council (U.S.). Child Development in Life‐Span Perspective. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1988.

- Keating, D. P. “Transformative Role of Epigenetics in Child Development Research: Commentary on the Special Section.” Child Development 87, no. 1 (2016): 135–142.

- Kim, P., and S. E. Watamura. Two Open Windows: Infant and Parent Neurobiologic Change. The Aspen Institute, 2015. https://ascend-resources.aspeninstitute.org/resources/two-open-windows-infant-and-parent-neurobiologic-change-2/

- Landry, B. W., and S. W. Driscoll. “Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents.” Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 4, no. 11 (2012): 826–832.

- Notterman, D. A., and C. Mitchell. “Epigenetics and Understanding the Impact of Social Determinants of Health.” Pediatric Clinics of North America 62, no. 5 (2015): 1227–1240.

- Parlato‐Oliveira, E., C. Saint‐Georges, D. Cohen, H. Pellerin, I. M. Pereira, C. Fouillet, M. Chetouani, M. Dommergues, and S. Viaux‐Savelon. “‘Motherese’ Prosody in Fetal‐Directed Speech: An Exploratory Study Using Automatic Social Signal Processing.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 646170. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646170

- Phillips, D. A., and A. E. Lowenstein. “Early Care, Education, and Child Development.” Annual Review of Psychology 62 (2011): 483–500.

- Siegel, D. J., and M. F. Solomon. Mind, Consciousness, and Well‐Being. New York: Norton, 2020.

- Swain, J. E., J. P. Lorberbaum, S. Kose, and L. Strathearn. 2007. “Brain Basis of Early Parent‐Infant Interactions: Psychology, Physiology, and in vivo Functional Neuroimaging Studies.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 48, nos. 3‐4 (2007): 262–287.