CHAPTER 34

DESIGN PROBLEMS AND OPPORTUNITIES PLAY: How do I decide what are the right problems to solve?

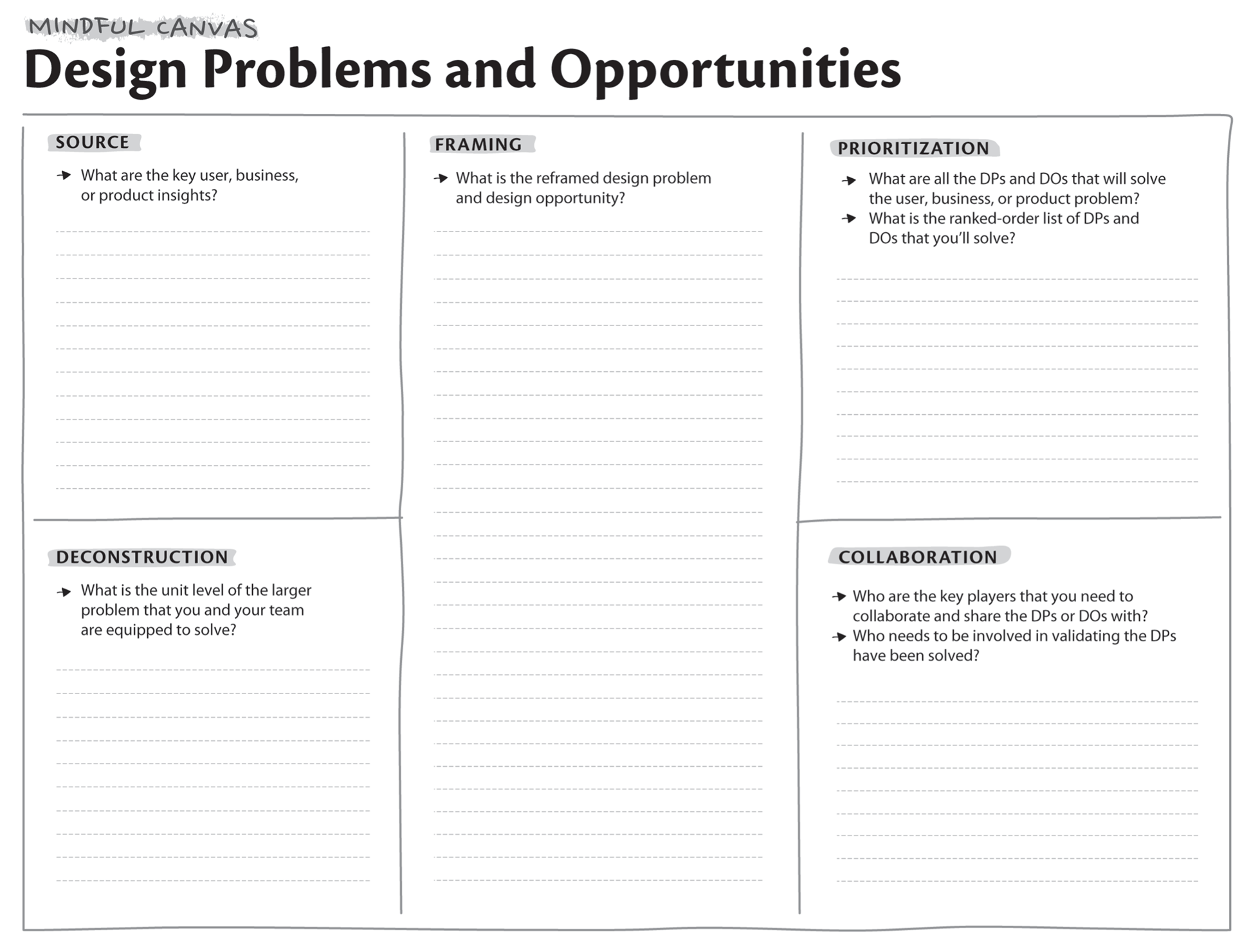

Too often, practitioners dive straight into solution‐ing before clearly defining the problem and determining whether it’s important to solve. Rooted in a deep understanding of user and business needs, design problems (DPs) and design opportunities (DOs) are reframed questions that catalyze breakthrough ideas and design. The DP and DO play will instill focus, propel teams and organizations from paralyzed inertia to excitement and progress, and ultimately lead to user delight and high business impact.

Who Are the Key Players in the Design Problems and Opportunities Play?

| ROLE | WHO’S INVOLVED | RESPONSIBILITIES |

|---|---|---|

DRIVER |

|

|

CONTRIBUTOR |

|

|

THE HOW

To build an effective design problem and opportunities play, you need to be mindful of:

1. Identifying the SOURCES of Insights That lead to DPs and DOs

All DPs and DOs can typically be sourced from three primary types of insights:

- User insights are collected from interviews and observations conducted by the user research team. They are a record of the pain points and/or joys that your users experience.

- Business insights are unique to one organization and come from intelligence gathered on the industry, business, or competitors (Chapter 28: “Experience Metrics Play”).

- Product insights are centered around a product or platform. They originate from product metrics and usage details or direct user feedback on the product.

2. DECONSTRUCTING the Larger Problem

When you arrive at a user, business, or product insight, further break down the identified challenges into sub‐components (Chapter 28: “Experience Metrics Play”). The goal is to understand all of the different variables that, when considered together, help answer the question of why the problem occurred in the first place. Break the larger problem down to its unit‐level problems, and focus on the ones you or your team are equipped to solve.

3. Correctly FRAMING the Problem

Now that you have a clear idea of what problem variables you will solve, it’s important to shape the problem statement. This will serve as your anchor moving forward. How you frame the problem will determine whether you are going after the right problem and consequently, how well the solution will solve the user, business, or product problem.

There are two ways to frame the problem:

- Design problems start with “How might we” (HMW) questions. A well‐framed “HMW” question turns your problem and insights into questions that beg ideation and participation from others. One mistake we often see is a tendency to include solutions in the framing of design problems. Good design problems don’t mention specific ways in which the problem will be solved, but rather ask how to achieve an end goal.

In the first example, “voice command” prescribes a solution rather than opening up a space to brainstorm all of the different ways the problem can be solved. The second DP avoids including any solutions in the problem statement and focuses instead on stating the goal—i.e. easing the chaos of shopping with children.

- Design opportunities start with “What if we” (WIW) questions. Design opportunities differ from design problems in that they transform challenges into problem statements that spur out‐of‐the‐box thinking, ultimately leading to solutions that question the status quo and bring tremendous delight to the user.

In this example, customers don’t expect the company to provide a sign‐up experience through a single interaction, because they are used to the industry norm of a long sign‐up process. However, the company is fully equipped to deliver that experience by bringing multiple departments together. A well‐framed design opportunity truly delights the user.

DPs and DOs can sit across multiple levels: UI, PX, and XT (Chapter 4: Experience Value Chain).

Design problems and design opportunities both respond to the same problem and challenge identified in the user, business, or product. However, design problems prompt solutions that answer “What the experience should be”; users expect them—they are table stakes. Design opportunities go beyond to build solutions that answer, “What the experience could be”; even though users don’t expect them, the solutions are within the team or organization’s current capabilities and will oftentime push their capabilities further.

4. Properly PRIORITIZING of all DPs and DOs Before Solving for Them

A large volume of ideas spurs originality. Brainstorm and ideate as many DPs and DOs as possible.

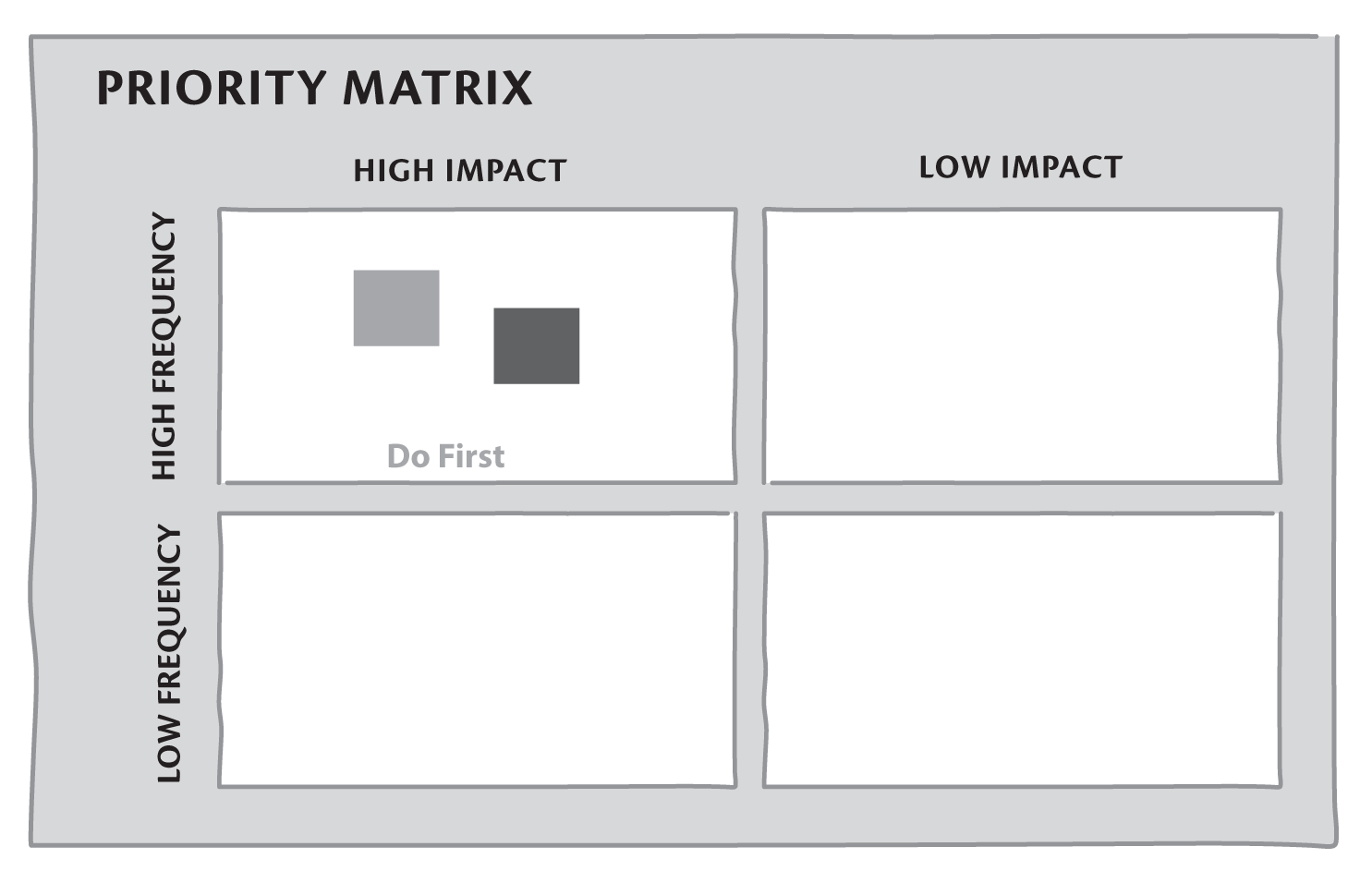

Prioritize your wealth of DPs and DOs. This way, you can surface the problems you should start solving and designing solutions for them. There are many ways to do so, including using a 2x2 prioritization matrix with an impact x‐axis and a frequency y‐axis, or an impact x‐axis and a feasibility y‐axis.

After prioritization, you’ll have a focused and ranked‐order list of DPs and DOs to tackle that will ultimately solve the user, business, or product problem.

5. Ongoing COLLABORATION and Hand‐Off

The next step for DPs and DOs will vary depending on the level (i.e. UI, PX, XT), scope (e.g. how big is the problem or opportunity), intent or overarching objective, and existing organizational capabilities.

Achieve traceability for each DP and DO (Chapter 40: “Detailed Design Play”); this helps govern and hold the team accountable for solving them. Document the source of the solution, the variation of solutions, the final solution, and the efficacy of the solution.

Typically, the prioritized DPs and DOs are given to the design team, which triggers the design doing process and collaboration with the product and engineering teams.

Here are some other hand‐off scenarios:

- White‐space brainstorming: If the DO reimagines how the product will evolve (e.g. what if the system didn’t exist?), then the next step is putting together a vision of your reimagined future state (Chapter 20: “Experience Vision Play”).

- Ecosystem mapping: If the DP or DO requires multiple departments to come together, visualize the entire ecosystem across departments (Chapter 18: “Experience Ecosystem Play”).

- Workflow improvements: If poor user experience is caused by gaps within existing workflows, then figure out how you can optimize the workflow (Chapter 39: “Workflow Design Play”).

- Design doing: If prioritized DPs and DOs are ready for the next stages of the design cycle, then pass them over to the design team to start ideating and building design solutions.

- Validation research: Once a DP has been designed for, validate its impact. The research team closes the loop on whether the DP was solved in real life with real users.

IN ORDER TO MAXIMIZE THE VALUE OF THIS PLAY

- Always trace the DP and DO back to the original business or user insight.

- Maintain a practice of insights curation (Chapter 29: “Insights Curation Play”) for all unprioritized DPs and DOs. This prevents knowledge drain, especially when key team members leave.

- Designers should always anchor back to the right problem whenever they are presenting their designs. Identify the problem first, and then show the design. This will ensure the team focuses on the problem rather than getting distracted by the design and will enable the designer to guide the conversation toward deriving a magical solution.

- Be vigilant. User problems and insights can be surfaced throughout the product journey, beyond the most obvious phases such as research and stakeholder interview.

RELATED PLAYS

RELATED PLAYS

- Chapter 29: “Insights Curation Play”