3

STRATEGIC INTENT

Now that you’ve gathered a number of weak signals, you need to brainstorm ideas that are the right fit for your organization. So next, we’ll walk you through the shaping of your organization’s strategic intent, which will provide direction for brainstorming and identifying Box 3 ideas.1 To paraphrase the Cheshire Cat from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, if you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you there.

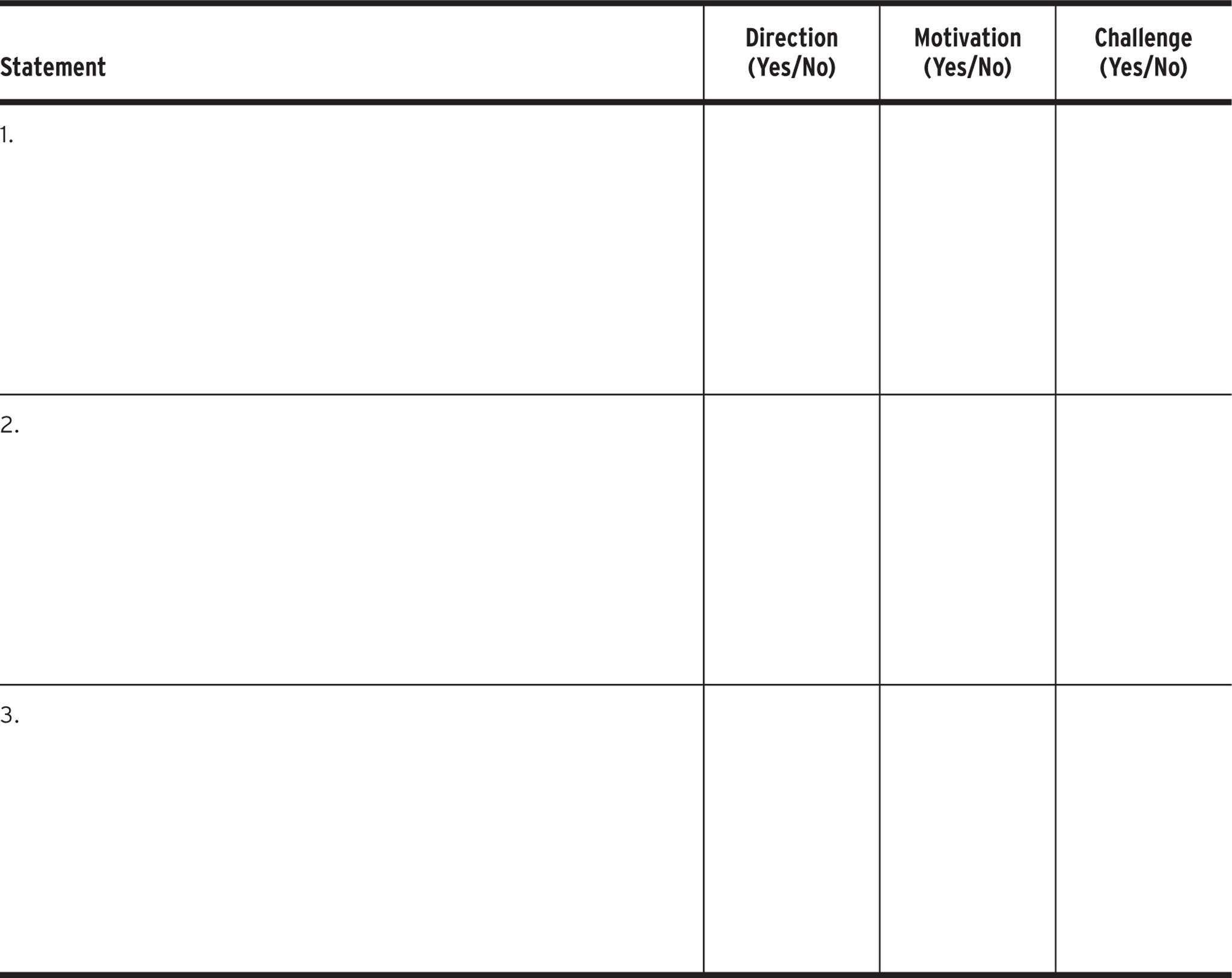

Unlike mission statements, which are sometimes generic, broad, and aspirational, a strategic intent statement must meet three criteria:

Direction: A strategic intent statement must galvanize your team to create the future. Direction is about the big picture, not all the steps you have to take to get there. One great example of making the big picture visual is that of Muhammad Yunus, founder of Grameen Bank, a microfinance and community development bank founded in Bangladesh. Yunus’s aspiration is to eliminate poverty. Just as dinosaur museums were constructed because there are no living dinosaurs to see, Yunus’s strategic intent is to create “poverty museums” after poverty, like the dinosaurs, no longer exists.

Motivation: A strategic intent statement must also create passion. Would employees be excited to go to work if the CEO said, “Our mission is to create shareholder wealth”? On the contrary, a statement that shows appreciation for employees’ capabilities helps them feel considerable personal meaning in their work and will go far in exciting people about creating the future beyond mere financial goals.

Challenge: To challenge employees to do something bold, a strategic intent statement must express a sizable possibility gap. Yunus’s intent to eliminate poverty meets the test of a huge possibility gap.

A strategic intent is a choice you make after evaluating what is changing in the world around you, what the implications of those changes are for your company, and what your aspirations are for the future. Strategic intent is about thinking big, dreaming big, and having an unrealistic goal.

We create our vision by starting with the future and working backward from there; we disregard the resource scarcity of the present. Successful organizations imagine the future in bold terms. The details are not fixed, but the big picture and the direction are clear and everyone is aligned. Why do we need an unrealistic goal? As human beings, we perform according to our expectations; we rarely exceed them. People are drawn to bold and challenging goals. Deep inside, the thought of climbing a mountain uplifts us in a way that the idea of scaling a molehill does not.

If your company has to become a leader in the future, you first have to imagine the future. Articulating a strategic intent that passes the direction, motivation, and challenge criteria is an important tool—as it provides scope and anchors the company in pursuit of its goals.

To develop a strategic intent statement, take the following steps:

Step 1: Imagine the future of your industry, building on the weak-signals exercise in chapter 2, and write down what you anticipate.

Step 2: Assess whether your current strategic intent, which your organization may have set earlier, is still applicable within that future context.

If yes, test for the three criteria—direction, motivation, and challenge—and refine as needed.

Step 3: If your strategic intent needs some work, divide into three teams to brainstorm three strategic intent directions. Think about what is changing the world, what those changes mean for your company, and what your company’s aspirations are, given those changes.

Step 4: Apply the three criteria—direction, motivation, and challenge—and assess which of the statements is the best fit for your organization.

Step 5: Test the strategic intent statement. For instance, if you radically change the customer set, value proposition, or value chain architecture, will the strategic intent endure the change? If the strategic intent statement doesn’t hold, then use the following lines to refine it further, for example, to ultimately ensure that it can target not only current consumers but also nonconsumers. Otherwise, leave the lines blank.

In early October 2015, the New York Times Company celebrated a remarkable achievement by clearing one million digital subscribers. What took the printed newspaper a century to achieve, the company’s websites and apps attained in just five years. The bet on the weak signal generated by the internet had paid off. In five years, the company had doubled the digital-only revenues to roughly $400 million.4

As the company imagined the future, it released a report titled “Our Path Forward,” which stated its ambition to double its digital revenues to more than $800 million by 2020. One way to achieve this goal was to double the number of engaged digital readers, who were the underpinning of the consumer and advertising revenue models.

The NYTimes realized that it needed to move from a print-era organization to a mobile-era one. Whereas the first two million subscribers, including the one million-plus newspaper subscribers, grew up with the New York Times spread over their kitchen tables, the next million had to be fought for and won with the Times on their phones. Furthermore, this goal had to be reached in an environment of relentless change in technology, consumer behavior, and business models.

The following intent statements illustrate how the NYTimes described its approach to the future:

- The NYTimes will continue to lead the industry in creating the best original journalism and storytelling.

- The company will transform the product experience to make the New York Times an even more important part of its readers’ daily lives.

- It will continue to develop new audiences and grow the Times as an international institution, just as the company once successfully turned a metro paper into a national one.

- The NYTimes will improve the customer experience for its readers, enabling them to more easily form and deepen a relationship with the New York Times.

- The NYTimes will continue to grow digital advertising by creating compelling integrated ad experiences that match the quality and innovation of the New York Times.

- The company will continue to provide the best newspaper experience for its print readers and advertisers while carefully shifting time and energy to its digital platforms.

- The company will organize its operations with a focus on its readers, not on legacy processes and structures.

Notice the word readers occurs in four of the seven bullets. The NYTimes must definitely cater to its readers, particularly as the print business declines slowly while the digital business expands rapidly and as both businesses will probably coexist beyond 2020.

When imagining the future, however, we must be open to heretofore-unimagined possibilities. In the case of the NYTimes, the company might have imagined that at some point, “readers” would consume content in other ways, such as video, and thus turn into viewers. Even from a US standpoint, 2015 was a landmark year, in which consumers spent more time consuming digital video than they did social media.5 With the benefit of hindsight, we can see the trend has been accelerating. By January 2019, as 4G data rates dropped below $2 per month in India, the volume of video streamed on smartphones had grown tenfold. People in India are using YouTube as a search engine. They find it easier to watch something than to sift through text, making India the country with YouTube’s largest audience in 2018.6 Thus, the strategic intent statement should not be limited to “readers” but should encompass “users” or “consumers” as well.

In building its strategic intent, the NYTimes could have gone in three directions:

Advertiser first, such as a focus on maximizing readership

User first, such as a focus on building loyal, paying, engaged customers

Something totally radical, such as an OTT TV provider (e.g., Sling TV)

The company decided to focus on users first, building a loyal, highly engaged, paying customer base. This decision doesn’t imply that the NYTimes should give up on advertisers as a business model. But the clarity in the company’s strategic intent helps its leaders understand the trade-offs when they have to make hard decisions. As a business leader, you may be tempted to say that you will focus on multiple dimensions of your business, but doing so would weaken the direction of your strategic intent statement.

We can imagine that, equipped with this backdrop, three NYTimes teams might have come up with the following strategic intent statements incorporating the direction test:

The NYTimes will be the best media company on the planet, built on the most loyal consumer base.

The NYTimes will inspire engaged consumers to lead active and ambitious lives and will do so through the best original journalism and storytelling in a digital-first world.

Whatever the weather, whatever the platform, the NYTimes will deliver the story that illuminates consumers’ minds throughout the world and throughout their lives.

As the example of the NYTimes shows, you and your team need to base your strategic intent statement on energizing your organization. The winning statement must pass the motivation and challenge tests.

You will also want to pressure-test your strategic intent to ensure that it is not too narrow; strategic intent must allow for many Box 3 ideas. For instance, does the signal of video proliferation discussed earlier get captured in the NYTimes winning strategic intent statement? For example, Google’s mission statement, “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” allows the company to pursue the direction of being in the news business. On the other hand, the NYTimes strategic intent statement doesn’t capture the search business.

Wrap-Up

Once you have gathered several weak signals, the next step in ideation is to develop a statement of strategic intent. Keep in mind these caveats when considering what constitutes a successful statement:

Strategic intent should be considered within the context of the nonlinear changes in the industry.

A statement of strategic intent must do three things: direct, motivate, and challenge.

Strategic intent provides a broad direction within which Box 3 ideas can be generated.