Chapter 5

Pricing Policy

Managing Expectations to Improve Price Realization

How should a company respond when a key customer announces that its next contract will be determined by a “reverse auction”? How should it respond when some of its customers are experiencing an economic downturn and ask for help? How should it deal with customers who resist a price increase necessitated by increased costs that all suppliers are experiencing? Responding to such challenges with ad hoc “price exceptions” rewards those customers who are the most aggressive negotiators, and ultimately alienates a company’s best customers. Those aggressive customers slow the sales process with increasing requests for “exceptions” that have to be sold internally. And they preclude any ability to exercise price leadership since it is difficult for competitors to adapt their strategies to prices that are neither consistent nor predictable.

A better solution to this challenge is to treat each request for a “price exception” as an opportunity to create a pricing policy that precludes the need for such requests in the future. Pricing policies are rules or habits, either explicit or cultural, that determine how a company varies its prices when faced with factors other than value and cost that threaten its ability to achieve its objectives. Some companies enforce rules regarding who in the organization has the authority to approve discounts: a sales rep up to 5 percent, his regional manager 15 percent, the vice president of sales 25 percent. Although these rules are often called “pricing policies,” they are not. They are personnel policies designed to mitigate the adverse consequences of undefined policies. Pricing policies would state explicitly the criteria that, say, a regional sales manager should use when deciding whether or not to exercise his authority to grant a 10 percent discount. Such a policy would be applied the same way by all sales managers to all similar requests for exceptions.

A customer’s purchase behavior is influenced by more than just the price and the product or service that the seller offers. It is also influenced by the expectations that the seller has created. Past experience, a buyer’s own and that of others about which he has become aware, drives expectations about what conditions are necessary to get a good price, and those expectations in turn drive the buyer’s future purchase behavior.

For example, a retail consumer may believe that a new fall fashion is well worth the price asked for it in September but still not buy it if she expects that the store, following its past behavior, will soon have a 20 percent off promotion when the price will be even better. A retail pricing policy of predictable discounting trains many retail consumers to wait for “the sale price.” To change that expectation, some retailers adopt and publicize an “everyday low price” policy, while others maintain regular discounting but offer “30-day price protection” enabling the customer to receive a credit for the difference between the regular and the sale price within 30 days of purchase. Changing the expectation that waiting is rewarded encourages more people to buy at the offered price, thus reducing the need to discount the price later. The same dynamic plays out—only more so—when businesses sell products and services to business customers who have more ways to influence the prices they receive through their purchase behavior.

EXHIBIT 5-1 The Interaction of Expectations and Behaviors

The behavior of sellers too is driven by expectations inferred from past experience. The seller’s most recent experience in the example above is that sales go up a lot during a period of discounts, but fall increasingly short of expectations during the weeks before discounting. If the seller forms expectations based only on that experience, he is likely to become even more aggressive in the discounting—perhaps starting the discount even a week earlier in the quarter to take advantage of customers’ increasing “price sensitivity.” For sellers to see the value in creating something like a 30-day price guarantee, they need to see the whole picture (as illustrated by Exhibit 5-1). Rather than simply reacting to past customer behavior, they need to look forward to understand how a systematic change in their behavior (for example, a new policy) could affect customers’ expectations in a way that would affect their future behavior.

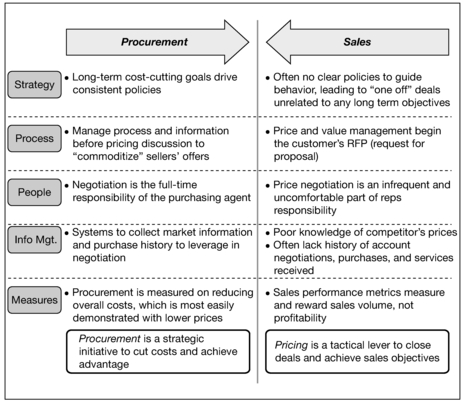

The difference between tactical pricing and strategic pricing is the difference between reacting to past customer behavior and acting to influence future customer behavior. If a seller or buyer understands only that half of the process that involves her own expectations or behaviors, it is impossible to be strategic. Unfortunately, in many business-to-business markets, where high-volume repeat purchasers negotiate their prices, buyers are ahead of sellers in thinking strategically (Exhibit 5-2). Under the rubric of “strategic sourcing,” they have developed systematic and sophisticated policies for managing suppliers’ expectations, while sellers often understand little about how expectations are formed in the buying organization. Buyers have goals and a long-term strategy for driving down acquisition costs, while suppliers rarely have comparable long-term strategies for raising or at least preserving margins.

EXHIBIT 5-2 Strategic Capabilities of Procurement versus Sales

For example, buyers often adroitly separate discussion of terms and service levels from the discussion of price—often leaving them off the request-for-proposal (RFP) to make all suppliers more comparable during a bidding process. They then pick a supplier who can meet their high service requirements, which are specified only after the bidding process. Sellers, on the other hand, often lack the corresponding ability to unbundle services to meet just the specs in the RFP, which would enable them to charge individually for better terms and services over-and-above those specified.

Buyers have full-time professionals to negotiate prices who are separate from those who specify or use the product, while the seller’s counterpart is a rep whose main job is customer service. The purchasing professional is rewarded for cutting acquisition costs or establishing conditions that increase future leverage, while the typical sales professional is rewarded simply for making the sale. The purchasing professional usually has access to a database of information about all the offers and counteroffers that the supplier has made to his company in the past, and often about the pricing and terms that other companies have done. A new sales rep usually knows only what is in the previous contract and on the invoices.

Policy Development

The process for developing good policies involves treating each request for a price exception as a request to create or to change a policy that could be applied repeatedly in the future. The more requests, the more likely it is that a policy, or the more fundamental price structure, is in need of review. In the beginning, if the firm has few clearly defined or consistently followed policies, a lot of potential deals will end up as requests for price exceptions. As new, well-thought-out policies are put in place, customers and sales reps will learn that ad hoc exceptions to policies will not be granted. The only requests for “special pricing” that should be considered are those involving situations not already covered by a policy. Creating the policies is not the responsibility of sales reps or local sales managers, since they do not have the perspective on the overall market or the authority to make the changes required to remedy this imbalance. It is the responsibility of management at a market level.

Putting a “no exceptions” stake in the ground is a key to making pricing decisions that are profit enhancing. Most discount proposals, whether to reduce price to win business or to increase price to exploit tight supply, have an immediate reward that is obvious but a corresponding cost that is delayed, diffused over more accounts, and less transparent. In contrast, pricing by policy forces companies to consider the impact on the entire market when making a pricing decision. It should involve asking whether it makes sense to establish a policy that the proposed pricing option could be offered to all customers like this one and still be profitable. Making the decision a policy question forces decision makers to think through the broader and longer-term implications of the precedents they are setting.

Pricing policies cover more than just discounting. They include the company’s pattern for passing along changes in raw materials costs (such as requiring that all long-term contracts allow for adjustments versus adjusting only after a fixed-price contract expires) and its pattern for inducing product trials. Pricing policies also deal with how a company will respond to low price offers made to its customers by a competitor. Any pattern creates expectations for how the company will deal with such issues in the future, and thus can change customers’ future buying behavior. Policies also influence how your sales reps sell and which ones succeed. Who is most rewarded at the company: the sales rep who sells at high margins by understanding customers well enough to communicate value, or the rep who drives big volume at a few accounts by understanding his company’s management well enough to make the case internally for price exceptions?

Ideally, policies are transparent, are consistent, and enable companies to address pricing challenges proactively. If your policies are transparent, customers need not engage in threats and misinformation to learn the trade-offs you are willing to make. Airlines have transparent pricing rules that none of us like (low prices only when purchased well in advance, charges for making changes, no transfer of tickets to another passenger), but we accept them because we know what they are. Consistency communicates that it is impossible to “game the system” by contacting multiple points in the company to find the best deal. Communicating policies proactively is much less contentious than telling a customer reactively that a proposal of theirs has, after some delay for review, been rejected.

Analyzing pricing challenges and developing policies to deal with them is an ongoing process, one that is generally the responsibility of a pricing staff overseen by a group of managers with collective responsibility to preserve or improve profitability. Over time, a company’s policies can become a source of competitive advantage—creating expectations that drive better behavior on the part of customers, competitors, and sales reps and empowering sales reps to offer creative solutions more quickly and with less wasted effort selling their ideas internally. Still, building that set of policies takes time, and policy-based pricing will lose organizational support if few of the initial applications produce positive results. To avoid that problem, the remainder of this chapter will identify the common challenges that call for policy-based solutions and describe successful policies that we have seen for dealing with each of them.

Policies for Responding to Price Objections

The most common, and therefore, most important domain for policy development falls into the arena of responding to price objections from customers with whom pricing involves a process of negotiation. The lack of policies for dealing with price objections is not only a challenge for companies that sell directly. Consumer goods manufacturers face just as much price pressure from powerful retailers—such as Wal-Mart, Carrefour, Home Depot, and Staples— as they do from consumers who switch to alternatives because of price.

The Problem with Ad Hoc Negotiation

To illustrate the problem created in price negotiation by non-existent or poorly enforced pricing policies, think about how the process commonly plays out badly for the seller. Imagine that to cover the increased costs of raw materials, your company announces a 5 percent price increase. When sales reps attempt to get their next orders at those higher prices, purchasing agents confront them with the assertion that the increase is unacceptable. How each sales rep responds to that resistance is critical to the success of this and any future price increases. Unfortunately, most companies lack consistent policies for how to respond, so that the mistakes of even a few can leave the company worse off than if it never even attempted the increase. The reason is that the response will create an expectation among the company’s customers about how to get a better price.

Let’s look first at what happens when a company has poorly defined or unenforced pricing policies. Imagine that when confronted by the purchasing agent, the sales rep looks flustered and says only that he cannot change any pricing without the approval of his manager. This simple statement will make all future negotiations much more difficult. The sales rep has told the purchasing agent (1) that his company makes price concessions to some customers and (2) that to get one, or at least to get one at the highest level, requires resisting until a sales manager is involved. In short, by communicating that it makes exceptions, the company and the sales rep have lost their price integrity. Given that lack of integrity, the purchasing agent realizes that either she must figure out how to exploit it or she will be paying higher prices than other buyers pay. A purchasing agent’s worst nightmare is that someone discovers that a competitor is buying the same product from the same supplier for less than she was able to negotiate.

Buyers exploit a lack of price integrity by adopting defensive negotiation tactics. These usually involve purchasing policies that shift the negotiation from one where the seller manages the buyer’s expectations to one where the buyer manages the seller’s expectations. The expectation that the purchasing agent wants to create is that the buying company views the seller’s product or service as essentially a commodity for which there are easy, cheaper substitutes. Creating this expectation involves minimizing direct contact between sales reps and users who could acknowledge the value of differences. It also involves creating at least the impression of a highly competitive market for the customer’s business.

We have seen many cases where a company lost market share at an account because it became more flexible in negotiating price exceptions. Once customers learn that their price is dependent upon creating substitutes, they qualify second and third sources for their business and solicit lower bids with promises of a higher share. Of course, they give their preferred supplier a “last look” chance to match those lower bids to retain a larger share. And every time the preferred supplier matches, it reinforces the value of maintaining competitive suppliers and minimizes the expectation that the supplier’s differentiation has a justifiable economic value.

Seeing this erosion of market share causes sellers to believe that their products and services have become more commoditized. Because they fear additional sales loss, they discount more and often cut expenditures for the differentiation that customers appear not to appreciate. If the company lacking price integrity is the market leader, the damage from a lack of price integrity is compounded. Competitors never know the real price against which they are competing, since there is no consistency. Their information about what you are offering on any particular deal comes from the purchasing agent who has an incentive to under-represent the prices and forgets to mention restrictive terms to qualify for them. As a result, competitors will on average imagine that the leader is pricing lower than it is, and so they will price lower than necessary to win sales.

The Benefits of Policies for Price Negotiation

Now consider the impact on expectations when the same scenario is managed with strong pricing policies that maintain price integrity. Your company has announced a 5 percent price increase to cover rising raw materials costs. When confronted by the purchasing agent, the sales rep knows that his company will back him in holding firm on the increase, even at the cost of a sale. He confidently explains to the purchasing agent why all suppliers will face the same cost increases and so cannot maintain their same quality and service levels without passing it along. Many purchasing agents will still refuse to accept the result at that point unless the firm’s price integrity has already been proven in the past. Some may only be bluffing. Others may be prudently planning to check what other suppliers are doing before deciding to accept the increase. Others, however, may be operating under a mandate to keep total costs from increasing.

Although your price increase is creating a problem for these buyers, it is the seed of an opportunity to change their behavior by changing their expectations. The sales rep who works for a company with pricing policies can be armed with more than just the confidence that he can lose the sale. He can also be empowered with pre-approved value trade-offs and discount policies that in a policy-free company would require review by someone higher up. The sales rep can build credibility with the customer by offering the customer win-win, or at least win–not lose trade-offs. If the purchasing department could get the multiple users in the company to place one consolidated order each month rather than many smaller orders, the sales rep explains, his company can cut the buyer’s shipping costs. If the purchaser would buy a wider variety of products from the seller under a multi-year contract, it would be possible to reach the volume threshold for end-of-year rebates exceeding 5 percent. If the purchaser would allow the seller’s technical people to talk with the users, they might be able to suggest some process improvements to cut waste by more than enough to offset the price increase.

To take advantage of these trade-offs, the purchasing agent would need to change purchasing behavior. To make the trade-offs, she would need to bring actual users into the decision process to evaluate them. If the policies are well designed, she will learn either that savings can come from working with this supplier rather than by threatening him, or that she already has the best deal available for her company. Once she develops the expectation that the best way to minimize cost is to work with her sales rep and that there is no reward to be had from deceiving him, she will become more open with information that enables the seller to identify other trade-offs that could be mutually beneficial. As buyers come to trust the process, there is no need for the seller to maintain multiple suppliers simply to gain leverage in price negotiations. This does not mean that the process will be free of conflict, anger, or occasional threats. But it will force the interactions toward a focus on value.

Regaining the ability to capture value in negotiated pricing requires more than training the sales force on “SPIN selling” or any other sales program. Value-based sales tactics need to be backed by a pricing process that is consistent with those same principles. Unless a company is selling a unique product to each customer, pricing should not be driven by a series of requests for one-off price approvals from the sales force, since the sales force then becomes little more than a conduit for strategies designed by the customers. Changes in price should be driven by consistent policies designed to achieve the seller’s market-level objectives. When the policies are aligned with those objectives and clearly articulated for the sales force, the sales reps (as well as distributors and channel partners) are empowered and motivated to sell on value rather than on price.

Policies for Different Buyer Types

EXHIBIT 5-3 Buyer Types

Given the growing power of some buyers, and the increasing transparency of pricing to all buyers, any profitable and sustainable solution for dealing with price objections must be codified in policies. But what policies? The answer to this question depends upon the type or types of buyers from whom you are encountering the objection. Exhibit 5-3 illustrates four general types of buyers, who differ in the importance to them of differentiation among suppliers within the product class (for example, how important is durability or immediate availability when buying office furniture), and the cost of search among suppliers relative to the potential savings. You need policies that enable your company to respond appropriately to price objections driven by the different motivations of these different types of buyers.

Value buyers purchase a disproportionate share of sales volume in most business-to-business markets. They have sophisticated purchasing departments that consolidate and buy large volumes, and they can afford the cost to search and evaluate many alternatives before making a purchase. They are trying to manage both the benefits in the purchase to get all the features and services that are important to them, as well as to push down the price as low as possible. The policies that the sales rep needs to deal with value buyers are ones that empower him or her to make trade-offs, while at the same time offering a defense against pressure on price alone.

The key to creating value-based policies is to understand every way in which your product or service might add more value to the customer than the product or service of a competitor, and every way that a change in a customer’s behavior could add more value to you. Then create a set of pre-approved trade-offs. For example, if a source of your value is higher quality service that competitors do not offer, you need to find a way that the service can be unbundled even if that is not the way you prefer to deliver your product. It may not even save you any money to unbundle it. But it gives the sales rep a low-cost alternative to walking away or simply giving in on the price without any cost to the buyer for the concession. With that lower cost option, the rep can call the bluff of purchasing agents at companies that do in fact value your differentiation. If too many buyers are actually taking the low service, lower price option, it is time for management to reconsider whether the service differentiation is really worth what they think it is.

The other option is to think of things the customer can do for you that would justify a discount. For example, could you create an end-of-year rebate based upon the customer buying more broadly from your product line, increasing volume by at least 20 percent, establishing a regular steady order that will not be changed less than seven days before the shipping date? Each of these illustrates a principle that we call give-get negotiation. The policy for dealing with value-driven buyers is that no price concession should ever be made that does not involve getting something from the other side. The price concession need not be fully covered by any cost savings to the seller, but it should eliminate any differentiation that the buyer claims not to value. This principle, which if the sales reps are empowered with pre-approved trade-offs can be established at the moment when the purchaser raises the price objection, educates the buyer that there is always a cost to price concessions. That cost puts a limit on the buyer’s willingness to pursue price concessions indefinitely. Once purchasers understand these new rules of the game, it also creates an incentive for them to think of new trade-offs that they might propose (for example, partnering on developing a new product) that would warrant consideration by the seller’s management as a new policy.

The fear that too many companies have is that if they adopt give-get tactics rather than simply concede to price objections with an ad hoc deal, they will lose too many value-driven customers. The problem with this thinking is that if you never test it, you never know whether the objections are driven by a lack of value or simply the expectations they you have created that objections are rewarded with concessions. Moreover, because value buyers know their market, they sometimes do not even give you the benefit of a price objection. You just lose their business because your product or service levels are beyond what they need.

By proposing trade-offs, you can learn from the research what value buyers are thinking. By listening to how they respond to proposed trade-offs, you can gauge whether the problem is that you are offering too much or that you are uncompetitive for the same things. If your proposed trade-offs are rejected and you lose business, then your prices may not be competitive. In that case, it is better to lower your price proactively by policy than to wait for each customer to object. Price integrity is worth more in the long run than the extra revenue you can earn for a while from the customers who are slowest to recognize that you no longer offer a good value.

Brand buyers (also known as relationship buyers) are those for whom differentiation, particularly of the type that is difficult to determine prior to purchase, is valuable but the cost to evaluate all suppliers to determine the best possible deal is just too high. Perhaps the buyer is new to the market and just lacks the experience to make a good judgment. The buyer will buy a brand that is well-known for delivering a good product with good service without considering cheaper but riskier alternatives. Other times, the buyer may have had positive past experience with a current supplier and the cost to evaluate another supplier versus any potential savings is too high; consequently, the buyer becomes “loyal” to the seller.

A price objection from a relationship buyer, or a customer satisfaction survey showing a decline in brand buyers’ belief that the company offers fair value for money versus competitors, is something to take very seriously. It can signal one of two things: that the brand buyer has been disappointed by the supplier relative to expectations or has learned something about market prices that leads him to expect that the price he is paying for security is excessive. A price concession is never a good response in the first case and may not be in the latter.

If the issue is a disappointment, it is important to understand the nature of it and make recompense, rather than giving a price concession going forward; such a concession signals to this customer that it is reasonable to expect such disappointment in the future, and the adjusted price reflects that less-than-adequate result. A client of ours in the printing industry failed to print and ship the client’s catalog when promised which, since the catalog was for seasonal merchandise, represented a serious breach of trust. The customer opened the catalog bid to other printers for the next year and the sales rep, having been berated by the customer, felt certain that the only way to keep the account was to slash the price. After understanding the high value that this customer placed on the quality and technical relationship that they had built up over many years with the printer’s technical personnel, we proposed a different approach.

The president of the printer went to see the president of this mid-size catalog company to express personally that what happened reflected an unacceptable misunderstanding of how important the promised mail date was to their business. He explained how, because the client was not one of the largest in the printing plant, their job had been given lower priority when problems arose. The president explained that they now realized what a poor policy that was for sequencing jobs. The president indicated that if given another chance, his company would put together a proposal by which the client could purchase the right to be, during the weeks of time-sensitive print runs, the top priority job in the plant. The deal would involve a sizable financial guarantee from the printer that its job would ship exactly as promised. By way of apology and to prove its commitment, the printer would give the client a large credit that would offset all of the cost of this service in the first year of a new three-year contract.

A few days later, the sales rep and the vice president of sales arrived with the proposal, including the option to “own” their desired time on the presses for what amounted to a 24 percent premium over the already high rate this customer had been paying. The proposal also gave the customer the promised credit to compensate for the prior year’s failure. After some further negotiation that slightly increased the size of the credit, the customer accepted the deal and expressed appreciation that the printer was finally giving their relationship the respect that they felt it deserved. Allowing this customer to negotiate a larger credit was acceptable because it was based upon the value lost by the past failure while still preserving the policy that the price the customer would pay reflected the value going forward.

Of course, if this buyer’s objection were driven not by any disappointment in the service but by a belief that it was already being exploited on the price, the solution would have needed to be very different. One way to avoid that problem is to understand the value you are delivering and have a policy to never let the price premium for the relationship buyer exceed that value. As important is the need to ensure that the buyer recognizes the added value that you are delivering. The key to doing that is to track all the value-added services that the customer gets and associate a quantifiable value to them. For example, a company can itemize differentiating features and services with prices for each on its invoice. Then, at the bottom, show a credit for the sum of those charges reflecting the fact that they are covered in the all-inclusive price.

Price buyers are the polar opposite of brand buyers. They genuinely are not looking for a feature or service that exceeds some level that they specify in advance. The clearest symptom of a price buyer is the “sealed bid” or “reverse auction” purchasing process. The buyer commits in writing to the specification of an acceptable offer and is distinctly unwilling to invest time in hearing about the value of an offer that exceeds those specs. He wants a proposal that simply communicates your capability to achieve the specs and your price. If managed appropriately, price buyers can be useful as a place to unload excess inventory, to fill excess capacity, or generate incremental profitability, but only if the risks are recognized and managed.

The only successful policy for dealing with price buyers is the following: strip out any and every cost that is not required to meet the minimum specification, create a “fence” if necessary to ensure that the product does not compete with product you have sold through more lucrative channels, and make no long-term investment or commitment. Branded pharmaceuticals companies have traditionally ignored developing markets such as India and China because of low prices, but rapid growth in those markets has caused big pharma to take a new look at how they could generate incremental revenue from patented drugs. They have done so by licensing reputable local suppliers to make local versions, without the use of the brand name or distinctive shape and often combined with local ingredients that would not be accepted in higher-priced Western countries. The companies earn incremental revenue from these price-buyer markets with minimal investment. Moreover, minimizing their investments in the market enables them to withdraw if their patents are not respected.

Sometimes value buyers, and even relationship buyers, will masquerade as price buyers in an attempt to extract reactive concessions from their preferred supplier. They hold a reverse auction, for example, that is widely open and they share the prices among the bidders with the goal to get their existing supplier to reduce its price. There are a number of tip-offs to look for to determine if this is a sham. One is that the buying company still spends a lot of time evaluating the differences among suppliers before the bid. Second is that its RFP is vague about the details of product and service specifications. Third is a lack of commitment to buy from the lowest price bidder who meets the specs. If any of these happen, then there is reason to believe that the buyer is not really ready to make the final decision solely on price.

There are two common policies that expose value and relationship buyers disguised as price buyers. One is to adopt and publicize a policy never to respond with a bid unless minimum acceptable product and service specifications are fully defined, enabling you to infer which lower quality bidders will be excluded and to understand exactly what the buyer is willing to give up. The other approach, recommended only when the volume at stake is very large, is to submit a bid that you can deliver profitably within the ill-defined spec but is explicit in stating the lower quality or service levels that reflect the “gives” you expect from the buyer in return for a lower price. If the customer wants what they have gotten from you in the past—such as the ability to place rush orders, to order shipments that are less than one truck load, and to demand higher-quality specs—you will enforce firm policies that will trigger unspecified additional charges for those services. Either of these policies by a supplier with an existing relationship will usually result in a return to more traditional give-get negotiations.

A common error that we see in dealing with genuine price buyers is the attempt to make them into value buyers by offering them a “promotional” price. The argument is that by giving a proven price buyer more quality or service than they have paid for, particularly when the users could really benefit from it, these customers will see what they have been missing and be willing to pay more in the future. In practice, exactly the opposite occurs. If price buyers learn that they can get priority service or superior quality when they really need it without paying for it, they have no incentive to ever change their policy of price buying. A better strategy is to let the price buyer know that you can deliver a much higher level of quality and service. When the price buyer needs a rush order or technical support because the low-priced bidder shipped defective product or failed to ship at all, a strategic pricer should have a policy to fill the order, but only at the highest list or spot price, perhaps including charges for a rush order, services, or anything else out of the ordinary. When the buyer has seen the cost of not dealing with a higher quality supplier, the seller may offer the customer a contract retroactively that would cover those services going forward at prices equal to what other buyers pay. If the price buyer declines the offer, at least you will have earned a good profit as an emergency supplier.

Convenience buyers don’t compare prices; they just buy from the easiest source of supply. Convenience buyers are value, loyal, or price buyers in categories where they spend more or buy more frequently, but will pay a price that is much more than the economic value defined in the market for a relatively small or infrequent purchase. They expect to pay a premium for convenience so price objections from them are rare.

Policies for Dealing with Power Buyers

A subset of value buyers is what we call power buyers, who control so much volume that they have the power to deliver or deny huge amounts of market share. They expect to get better prices than any other buyer because of that power. As one supplier reported being told by a big box purchasing agent, “We expect your price to us to cover your costs. Earn your profits from somebody else.” The worst of these was General Motors, which bankrupted most of its suppliers before bankrupting itself. In contrast, retail power buyers—such as Wal-Mart, Home Depot, and Staples—have increased their market share profitably over the past twenty years and are still expanding into new product lines. Power buyers have also arisen in the market for hospital supplies as integrated hospital networks and as “buying groups” of independent hospitals. Buying groups are not really buyers, but associations of buyers that increase their power to negotiate deals collectively by refusing to buy from suppliers that have not signed a contract with the group. Dealing with power buyers reactively is risky; a seller is almost certain to suffer a decline in profitability as a result.

So how can a seller deal with power buyers proactively? First, stay realistic. The effect of power buyers is to reduce the value of brands. Many companies that were seduced by the big volume of power buyers have lost their profitability as a result. Their mistake was to think of power buyer volume as purely incremental, leading them to cut ad hoc deals without thinking about the effect on the overall market. If a brand has enough value to consumers that they will go to a store that has it rather than accept another brand from a store (or a buying group) that does not, then the brand has value to the power buyer beyond the margin on that product. The brand can draw store traffic. Retailers competing with the big-box stores pay more than the power buyers precisely because the brand can draw a buyer to them. For example, Benjamin Moore paints have high value to local hardware stores and home centers not just because they have high customer loyalty, but also because they are not available at Home Depot or Lowe’s.

Still, in many markets, power buyers control so much volume that one cannot grow without them. For brands without broad customer recognition and preference, the broad distribution and access to volume that power buyers offer may be the key to profitable growth. Even companies such as Procter & Gamble with strong brands have found dealing with power buyers profitable, but not on their terms. Here is how others have made the choice to deal with power buyers and still preserved profitability.

MAKE POWER BUYERS COMPETE. Many companies with strong brand preference miss a big opportunity by framing the strategic issue poorly. They ask themselves whether they should continue with their traditional retail channel, targeting customers who are less price-sensitive, or sell to power buyers with their high volumes at lower margins. This misses a third option: sell to one power buyer in a segment exclusively giving it a pull advantage over competing power buyers. Martha Stewart certainly got higher margins from Kmart because of her exclusive contract than she would have gotten from selling Martha Stewart products to all big chains.

QUANTIFY THE VALUE TO THE POWER BUYER. There are many ways that a brand can bring differential value to a big-box retailer. Even if the retailer already has someone as a customer, the brand can drive store visit frequency. Disposable diapers are very valuable to Wal-Mart because their bulk requires frequent visits from a high-spending demographic group. A large manufacturer that is capable of serving power buyers everywhere it operates also reduces acquisition costs for such buyers.

ELIMINATE UNNECESSARY COSTS. The most difficult challenge to manage is trying to serve both high-volume power buyers who are unwilling to pay for your pull marketing efforts, and non-power buyers who value your brand because you support its marketing. One option is to specialize in serving only power buyers, enabling the company to eliminate costs of marketing and distribution. Shaw Industries, the largest carpet supplier in North America, squeezed costs from fiber production, carpet manufacture, and distribution by totally aligning itself to sell massive volume though Home Depot, Lowe’s, and large retail carpet buying groups.

SEGMENT THE PRODUCT OFFERING. There is no need to offer exactly the same product through a power buyer and through traditional channels where there is a conflict. Although John Deere sells products through Home Depot, it does not sell exactly the same products as through distributors. In the case of some packaged goods, only large sizes are available though Wal-Mart, Target, and other big-box retailers. These steps obviously do not entirely prevent the potential cannibalization, but they do reduce it.

RESIST “DIVIDE AND CONQUER” TACTICS. Power buyers get their power from their ability to deny a brand or product line any volume through their stores or buying group. The key to their success is to structure the discussion as being about the pricing of each of the manufacturer’s products individually. As a result, they maximize the competition for each product line and minimize any negotiating benefit that the supplier gets from offering a full line. Thus a large hospital buying group will tell a medical products manufacturer with nine product lines that there will be nine separate buying decisions, occurring at different times, for each product line. The implication for the seller is that, in the absence of the best price for each, it could end up with a few orphaned products that are excluded from the buying group’s distribution channel.

If you have a product line with some strong brands, you do not need to react passively to purchasing policies that undermine your advantages; proactively set policies of your own. When a large medical products company was confronted with these divide and conquer tactics, it simply returned multiple bid forms for each product with different prices, adding a line to the top margin of each specifying the conditions under which those prices would apply. The lowest applied only if all the manufacturer’s products were approved by the buying group, while the highest would apply if only a subset were approved. The hospital buying group hated this tactic, but the seller maintained its policy, explaining how the value of the channel to it was vastly reduced without complete acceptance of its product line. Recognizing the cost of losing all the seller’s products, some of which had large market share among members, the buying group approved all the products.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember in dealing with power buyers is to be emotionally prepared for them to be bullies who have seen intimidation tactics succeed. If you are confident of the value you offer and you are willing to unbundle differentiation that you know the customer values, be prepared for the fact that someone high up in purchasing may become furious. He may demand to speak to your CEO and threaten unspecified consequences of a damaged relationship with his company. If and when that happens, remember that power buyers who do not need you do not get mad; they can easily get others to supply them. They get mad because they are frustrated that they are not going to get the lop-sided deal that they expected.

Policies for Managing Price Increases

One of the most difficult discussions to have with a customer involves telling them that you will increase their prices. One of our clients in the New York metro area actually had a customer in the habit of throwing things—particularly shoes—at sales reps who proposed pricing that he did not like. Other customers would quietly ignore the increase when placing an order but, when paying bills, adjust them to reflect the old prices and return the invoice with a check marked “paid in full.” As a result of being cowed by such antics, this company typically realized on average less than half the amount of the increases, with customers who already paid lowest prices being the ones who avoided paying more. There are two very different occasions that call for increases, and well-designed policies can help to make all of them more successful.

Policies for Leading an Industry-Wide Increase

The most important increase to achieve quickly is the one that results from a large, sustained increase in variable cost of production or a shortage of industry capacity. These should be the easiest price increases since all suppliers are facing the same problem. There is no real alternative for the customers, regardless of how difficult the increase may prove for them. Problems arise, however, from poorly designed policies that fail to manage expectations. Good policies can influence expectations in ways that help such increases get a better reception.

Even when customers realize that a price increase is ultimately inevitable, none wants to be the first to take it. They do not want to be the first to tell their customers that their prices are increasing, or the first to tell their investors that their margins have declined because of rising prices. That means that they need to trust that their competitors are all taking the same hit. The only way to get the first large customers to go along is to make them confident that doing so will not put them at a competitive disadvantage. Your policy must be that you will not back off the increase for anyone without doing so for everyone who is a customer in the same industry.

There are a few things you can do to create the expectation that taking the increase will not put them at a competitive disadvantage. First, before you announce the increase, let it be known publicly why the increase is necessary for the industry as a whole based upon costs that the industry is incurring or demands on capacity. Listen carefully for similar sentiments that all of your major competitors recognize the same need before proceeding. Second, announce the size and effective date of the increase, stating exactly which product lines are increasing by how much. Explain the cause and effect relationship (for example, energy accounts directly or indirectly for X percent of costs and that translates into Y percent price increases). The public announcement reinforces that this is an across-the-board increase and insulates your sales reps from any personal responsibility for it.

Third, if customers are fearful that their competitors will not have to take the increase or will not take it as quickly, empower them to give your most important customers a transition guarantee. If you are the supplier to their competitors, you guarantee that if you agree to a lesser or delayed increase with any of their major competitors for the same product and service, they will get the same concession retroactively. If they are concerned that a competitor who is served by one of your competitors will not get the increase, you might agree that you will delay their increase until the effective date of a competitor’s increase. All of these will help create the impression that the cost increase problem is one that you are willing to solve together in a way that recognizes their legitimate business needs as well as yours. Because it is easier for any individual customer to accept the increase given these conditions, it is more likely that all will ultimately accept it.

Under no circumstances should you back off on the full increase for customers who are more resistant while leaving loyal customers to take it, a common practice. Although such a policy can generate greater return in the immediate quarter, it reinforces that resistance pays and outrages good customers whenever they learn that they have been taken advantage of. On the other hand, if a major competitor fails to initiate a comparable price increase, a general rollback may be necessary. If so, contact your customers proactively to let them know that you are protecting them by temporarily suspending the increase out of concern for their competitiveness. The increase will automatically be reinstated when it can be accomplished without putting them at any disadvantage. This builds trust with your customers, keeps the price increase agreement with them in play, while letting your competitor realize that there is nothing to gain from delay.

Finally, there are situations where you can safely make concessions for good customers, but only ones that involve the timing, not the fact, of the inevitable increase. For example, you can build loyalty by being sympathetic that they may have some fixed price commitments yet to be met. For volumes necessary to fulfill those contracts, you can legitimately agree to share the pain. Thus a customer receives the concession near term by agreeing to the increase going forward.

Policies for Transitioning from Low One-Off Pricing

In markets where volume comes mostly from repeat purchasers, it is difficult to transition from poor policies to good ones all at once. Customers have already developed expectations that they can get rewards from certain behaviors. They will continue those behaviors for a while until their expectations change. The change takes time within the seller’s own company, too; marketing and sales management needs that time to develop good policies, and the plans to carry them out. We have seen the move to policy-based pricing fail when management implements a rigid fixed-price policy of no more discounting without a plan for the transition.

To minimize the risk of transition and create time to test new policies for managing price variation consistently, one needs to begin with policies for managing the transition. Chapter 8, on pricing strategy implementation, describes a technique called price banding that enables managers to estimate how much of the price variation is illegitimate, both on an aggregate and a per account basis. The first policies should focus on managing the outliers: “out-laws” who now enjoy prices much lower than other customers for the same products, service levels, and commitments, and the “at-risks” who are paying more than can be justified relative to the average.

The first step is to identify the outlaws and how they got that way. The reason to start here is because they are the least profitable accounts, so there is less at risk if they take their business elsewhere. These outlaw accounts pull down other customers over time—either as a result of information leaking into the market about their pricing or because their competitive advantage in purchasing enables them to take share from others who buy at a higher price. If an outlaw is in a unique industry or different market from other customers and the low price reflects low value and low cost-to-serve, then an amendment is called for in your price structure that articulates objective criteria to qualify for the price and defines fences necessary to keep it from undermining your general price level. When there is no logical rationale for the low prices these accounts pay, an effective fence means to make an outlaw and others like him legitimate. That requires figuring out how the outlaw got such pricing in the first place and creating a policy to correct that mistake. If the original reason for such low pricing no longer exists (for example, a service mistake in the past led management to allow a discount to compensate, or the price reflected expectations of volume that never materialized), the customer needs to be confronted with that reality. Most importantly, the customer needs to be contacted by someone above the sales rep (the level dependent upon the size of the customer) to communicate that, while the customer has gotten a much better deal than others in the past, top management is unwilling to continue pricing that is unfair to other customers and unhealthy for the supplier.

With the bad news delivered unequivocally by management, the sales rep is now free to initiate a give-get negotiation in an attempt to save the account. He can contact the customer to learn if there might be some trade-offs they would consider, to mitigate the size of the mandated increase. Various concessions on the part of the customer consistent with those made by other customers could reduce some costs. With the ability to use a second or third source as a bargaining chip now unnecessary, the buyer might even be willing to sign up for an exclusive supply contract to qualify for a discount that would reduce the impending increase.

Finally, the firm may create a policy authorizing a period of transition to a legitimate pricing level in steps. An outlaw buyer who agreed to either an exclusive contract or minimum “must take” volumes under a long-term contract (say 18 months), would then be allowed to take the necessary price increases in steps: one-third of the increase becoming effective immediately, one-third in six months, and the last third in 12 months. What makes this effective is that the purchasing agent will be able to argue that he precluded an average increase over the contract that would have been twice as large as originally proposed and pushed realization of most of it to the back end. What is important to the seller is that by the end of the contract, the buyer will be purchasing at a price comparable to what other customers pay.

Of course, some of these outlaws will be genuine price buyers who may not accept any increase. Walking away from such customers, and publically acknowledging it as a good business decision, signals your resolve externally and internally. It will communicate a newfound commitment to doing business only with good business partners, and put others who may be masquerading as price buyers on notice that there is a potential cost. Unless your industry has excess capacity, it might also strain your competitor’s capacity with low margin business. If that makes it more difficult to serve some of their higher margin customers well, if only during a transition period, it gives you the chance to win some more profitable volume.

Policies for Dealing with an Economic Downturn

Pricing policies are most likely to be abandoned when the market enters a recession and sales turn down. Revenue then seems much more important than preserving profitability in the future. But unmanaged price-cutting in a recession not only undermines price levels that you will want to sustain in the later recovery, it can trigger a price war that makes all competitors worse off while still in the downturn. Fortunately, if a company thoughtfully manages pricing by policy though the downturn, it can minimize the damage in both the short and long run.

First, you must enforce a firm policy not to use price to take market share from close competitors during the downturn since they can easily respond with price cuts of their own. (But you can and should retaliate selectively against price-based moves by close competitors, as explained in Chapter 11 on managing price competition.) Safeway, which initiated a supermarket price war in 2009, increased its share of revenue but tanked its share of profits. Smarter competitors, such as Winn-Dixie, promoted their high-margin house brands to help thrifty shoppers cut costs, and weathered the recession with much less damage to themselves and their markets.1

In business markets, the value that some products can justify is tied to the health of their customer’s markets. For example, the value of a page of advertising in a magazine or space at a trade show is related to the size of the market for the product being advertised. In 2009, the return from advertising real estate was not what it was in 2008. In such markets, particularly when variable costs are low, sellers sometimes “index” their pricing for customers willing to make long-term commitments, with the index tied not to their costs but to market conditions in their customer’s market. Such a policy supports customers and maintains volume while times are difficult while establishing an automatic mechanism for price increases when customers can better afford them. An alternative is to unbundle elements of your product or service that the customer can no longer afford (such as, new product development and technical support), even though they value them. The point in all these cases is that these price discounting options can be designed to expire when they are no longer needed and do not directly threaten competitors.

But what can a company do to gain volume during a downturn when demand from its current customers is shrinking but taking share will only trigger a price war that will shrink the market further? As discussed in Chapter 3 on price structure, there are various ways to attract a new, more price sensitive segment, without cutting price to most of your existing customers. Moreover, when you have excess capacity, the cost to serve a new segment is minimal. Although you want to maintain policies that protect margins in the market where you are invested for long-term growth, you have nothing to lose from price competition, even of the ad hoc variety, in markets from which you hope to gain incremental business only short term. For those markets only, a policy of one-off pricing to fill excess capacity can be worth pursuing if the business can be carefully fenced.

For example, one high-end chain of hotels in Europe, which would never consider serving tour groups in good times, approached tour companies catering to small groups of high-income travelers with some very good deals. They brought in both incremental revenue and introduced their chain to a market segment of people they would want to have as nightly guests, while still enabling themselves to exit the tour segment in better times. Our commercial printer client approached direct mail advertisers accustomed to accepting poor quality from printers who use inferior presses. For mail circulars and newspaper inserts only, they offered better quality that nearly matched what advertisers were paying already. The low-end competitors could not match the offer, and the company won some incremental contribution that kept its press operators employed during some lean months.

Policies for Promotional Pricing

A discount to induce product trial is a legitimate means to gain sales, but poorly managed can have the effect of depressing margins. For search goods, the discount is the incentive for the customer to investigate the supplier’s offer. For experience goods, it is the incentive to take the risk of what could turn out to be a disappointing purchase. The size of the promotional discount necessary to induce trial can be mitigated by policy. A liberal returns policy if the customer is unsatisfied is one way to take away the risk of trying a product at full price. Bowflex does not discount its unique, high-end exercise equipment. But it combines direct-to-customer value communication with a money-back guarantee requested within the first six weeks of delivery. If product performance is measurable objectively, a performance-based rebate policy can accomplish the same thing. Rebating is becoming a common means for pharmaceutical and medical device companies to win acceptance of higher-priced products with as yet unproven differentiating benefits. When Valcade, a cancer treatment, was deemed not cost-effective and rejected for payment by the British National Health Service (NHS), the company did not agree to reduce its price. Instead, it came back with a new offer to guarantee effectiveness without lowering its premium price. The company would refund the entire cost of the drug for any patient who did not show adequate improvement after an initial period of treatment. The effect of this policy on the net average price remains to be seen, but the guarantee won approval for payment within the NHS and created potential for the company to earn higher profits if justified by superior performance.2 By putting money on the line, the company raised expectations both within the NHS and with other payers and clinicians that the product probably will produce the superior treatment outcomes that the company claimed, which will increase its market share.

For consumer products, promotional pricing is one of the most important issues for which a company needs pricing policies and a process for reviewing their effectiveness. Even companies that have established brands with large market shares face the problem that a high percentage of buyers will leave the market or, particularly in the case of food products, will become “fatigued” and look for something different. Consequently, manufacturers must constantly win new customers to maintain a fixed market share. Promotional discounts are often a very cost-effective way to educate consumers, particularly for frequently purchased consumer products, which are usually experience goods.

The easiest way to induce trial with little additional cost of administration is simply to offer the product at a low price for a time, say one week each quarter. For frequently purchased products sold through retailers, the sales increases resulting from such “pulsed” promotions are usually huge—easily justifying the deal if looked at in isolation. But there are various reasons why a company might want to ban such promotions as a policy. First, there is some evidence that when a product is bought at a promotional price, it depresses willingness-to-pay for the product in the future. Second, both consumers and retailers will stock up on the product when promoted, giving the appearance of a big increase in volume that simply depresses sales in later periods. There are categories, usually among food products, for which stocking up is a good thing. The more inventory people have of sodas and snack foods, for example, the more they consume. For most products, however, stocking up at promotional prices simply reduces the average price that customers pay while educating them to wait for the discount.

Consequently, a policy of limiting the availability of promotional discounts and targeting them to prospective buyers is often advisable. One way to do this is with coupons. Coupons have the advantage of limiting the ability of already loyal customers to stock up. With new scanner technology, retailers offer manufacturers the ability to print coupons on cash register receipts for customers who have bought competing products, or a combination of items that indicate that they might be good prospects for something that the manufacturer wants them to try. Rebates can be offered on the item but be limited to one per family.

Many service companies are in need of more disciplined policies for pricing to induce trial. Cable TV companies offer large discounts to sign up new subscribers for a year, as do newspapers and magazines and mobile telephone services. The problem in many of these cases is that, at the end of the discount period, they have to go back to the customer and ask for a much higher price to continue the service. A high percentage of those customers balk, knowing that either they can win an incentive from another supplier to try that supplier’s product for awhile, or can wait a week or two and sign up for another incentive from the same supplier who just tried to raise their price.

None of this should be surprising given what we have learned from the study of experimental economics.3 Once someone spends 6 or 12 months enjoying a service at one price, renewing it at a higher price is viewed as a “loss” to be resisted. No services company should ever use a discount on the service price as its means to induce trial. Instead, it should create an inducement that maintains the integrity of the price and builds the habit of paying it. For example, a far better inducement to purchase is a “free” gift for signing up—such as the choice from a list of new best sellers for signing up for a magazine, or $300 in pay-per-view credits for signing up for a year of cable TV. After the initial commitment, the incentive is gone but the customer is paying the monthly cost that reflects the value. As a result, there is no perception of “loss” that drives away subscribers at the back end.

Summary

Good policies cannot magically make pricing of your product or service profitable, but poor ones can certainly undermine your ability to capture prices justified by the value of what you offer. Good policies lead customers to think about the purchase of your product as a price-value trade-off rather than as a game to win at your expense. As such, they are an essential part of any pricing strategy designed to capture value and maintain ongoing customer relationships.

Notes

1. “Winn-Dixie CEO: Supermarket Pricing Rational, No Price War,” Dow Jones News Wire, May 12, 2009.

2. “NICE Responds to Velcade NHS Reimbursement Scheme” PMLive.com, June 7, 2007.

3. Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler, “The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (Winter 1991): 193–206.