8

Your connections matter: which matter most?

Littered with used oxygen tanks and rubbish, the Mount Everest base camp has played temporary host to the numerous climbers wishing to reach the summit of this 29,000-foot peak. Base camp serves many purposes, one of which is to acclimatize climbers to the high altitude.

Another purpose is to act as a central information hub for the climbing teams perched high above on this Himalayan monster. With the advent of wireless technology, climbers can stay in close contact with their base camp brethren. Not unlike an air traffic control station, climbers attempting to climb Everest can communicate with others at the base camp to learn of incoming inclement weather.

As a climber, communication with base camp can be a lifeline. Knowing that a storm is approaching can be the deciding factor for whether or not to attempt the summit. Not knowing that a storm is approaching can change a potentially successful ascent into a deadly adventure.

Put yourself in this situation … you and a team of climbers are perched at nearly 28,000 feet above sea level, with winds whipping around you and temperatures that haven’t seen zero for days. You have just spent your thirtieth night on Mount Everest. It has taken you just over two weeks to get from base camp to this, your last overnight site before reaching the summit. You awaken at 5 a.m. with a pounding headache and spells of dizziness that have become the rule rather than the exception over the last several days. More than anything, you want to find your way to the summit and then quickly (albeit safely) make your way off this brutal mountain.

As has become the daily ritual, your team leader uses his satellite telephone to speak with base camp. Base camp is in contact with various teams of climbers at several locations on the mountain. Each team on the mountain has another vantage point of the cloud and storm systems. Each team can provide critical information about changing weather. For the first time in seven days, your team leader hears that the weather appears to be stable – for at least a few hours – enough time to get to the summit and back to safety. Your leader signals your team to prepare to ascend. You pack your gear and take off for what will be a long, tiring, but safe last 1000 feet of this climb.

Entrepreneurial connections

It’s not what you know; it’s who you know.

Business wisdom from an unknown source

Choosing to communicate with base camp before attempting a summit seems like the obvious choice. With precious little oxygen and difficult climbing a given, why risk adding fierce weather to this already daunting mix? While lack of oxygen doesn’t play much of a role in starting new ventures, the fierceness of competition can make you just as dizzy. The pace of technological change can create new markets in a heartbeat. Companies with strong networks of contacts having varied vantage points – including those of customers, suppliers and others in the industry and related industries – are more capable of anticipating and understanding forthcoming changes and are therefore better prepared to deal with them. Likewise, entrepreneurs who surround themselves with a strong network up, down and across the value chain are well positioned to gauge the ever-changing market and modify their offerings, operations, organization and processes to meet the needs of a changing business climate.

Put another way, the ability to combine the tenacity for which entrepre- neurs are legendary with a willingness to pivot – often due to new information that wasn’t available earlier, including changes in the market or competitive environment – can make all the difference. Sometimes, such changes are favourable ones. Good luck can help an entrepreneurial venture. But good luck is most likely to pay off when those in charge have the right connections required to help them respond to new information quickly and adroitly. Otherwise, it is unlikely that the company will be able to take advantage of good luck when it shows up. Without the information sources to tell you when pivots are necessary, all the willingness in the world will do you no good.

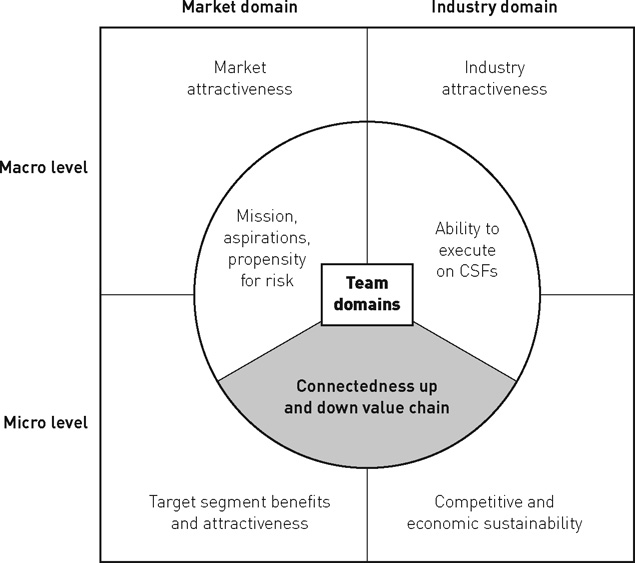

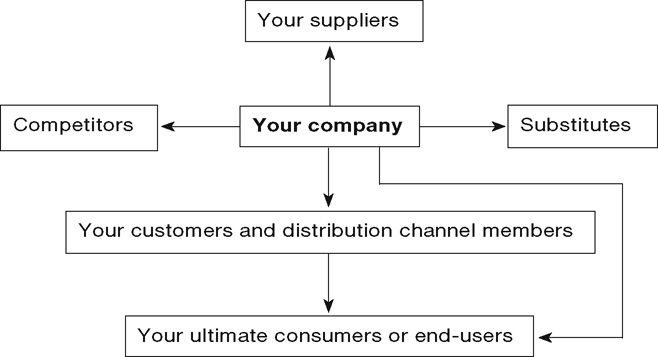

Thus, in order to be prepared to make the right pivots at the right time for the right reasons, you should ask how connected you and your team members are up, down and across the value chain as shown in Figure 8.1 – with suppliers and customers, as well as competitors in your industry or substitute industries – to address this concern. Connections with suppliers (up the value chain), with competitors (across the value chain) and with distributors, customers, consumers or end-users (all down the value chain) can provide crucial leading-edge information that could spell the difference between success and failure at an important juncture in the life of your business. If you’re not yet sufficiently connected, start building your network now!

figure 8.1 Connections in all directions

In this chapter, we’ll examine the case studies of two companies. As we’ll see, Virata’s connections in the UK and Europe enabled it to change its business completely to take advantage of a new application for which its technology happened to be extremely well suited. Digital Equipment corporation, on the other hand, simply failed to adapt to several marketplace changes – including the PC revolution – and found its minicomputer business obsolete. In both of these case studies we examine how just having connections is not sufficient – it’s having the right ones and having the ability to understand and act on the new information, even if it’s not what you want to hear. We then examine this domain from an investor’s perspective, so that you may understand better what investors will look for in your entrepreneurial team. Finally, the chapter closes with lessons to be learned from these two case studies for assessing your opportunity and the team you’ve assembled – or need to assemble – to pursue it.

Virata gets lucky. Why?1

Virata is not exactly a household name. We don’t sip Virata coffee. We don’t shop in Virata stores or ride in Virata cars. We don’t talk on Virata tele- phones. Or do we?

If you dialled up your high-speed DSL connection today to bid on that special something on eBay, then your data probably passed through a Virata chip. If you bought a book from Amazon via a DSL connection, then you probably used Virata hardware and software. If you checked your email using a high-speed DSL connection, then it went a lot faster because of Virata.

Virata, a British company that grew out of technology developed in the research labs of Cambridge University, provides communications processors and the relevant software that enable the world’s telephone companies to compete for the growing demand for high-speed digital access. But getting there wasn’t easy.

With roots dating back to 1986, Virata was an offshoot of the Olivetti Research Laboratory in Cambridge, UK, where Andy Hopper and Hermann Hauser had been leading research into a new technology called Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM). ATM had what Hopper and Hauser thought was an important advantage over other competing technologies: it could simultaneously handle voice, video and data transmission over local area networks (LANs) and wide area networks (WANs), and it did so at high speed. With technology valued at $6 million and seed capital from Olivetti, 3i and private investors, Virata was spun out of the Olivetti lab in 1993. With premises in Cambridge, it was given a chance to make its name developing and marketing equipment for LANs.

Ethernet, an older LAN technology that dated back to the 1970s, was not well suited to video and voice, since these time-dependent applications required information to be delivered in a constant stream. Ethernet separated data into packets that were distributed through different routes and reassembled at the receiving end. Ethernet worked fine for data, but not for voice or video. Garbled conversations or jerky images were the result.

A better mousetrap

Hopper and Hauser thought the need for voice and video would grow, so their new company soon began marketing video servers, switches and network interface cards that together comprised a complete ATM solution for LAN networks. Their ATM25 switch was the fastest in the world at the time, operating at 25 megabits per second compared with the 10-megabit products that the Ethernet providers offered. In 1994, with its new headquarters and sales office in California, to tap what was expected to be the first market for this new technology, Virata was off and running.

Like many technology companies, however, the cost of developing the technology outpaced the meagre early revenues. Thus, in 1995, with ATM all the rage in the venture capital community, Virata secured a first round of venture capital led by two prominent Silicon Valley firms, Oak Investment Partners and New Enterprise Associates, raising another $11 million for about 30 per cent of the company. As Hauser put it, ‘Venture capitalists are basically “sector lemmings”. When a sector is as hot as ATM was at the time, venture capitalists have got to have some ATM investments. We had one of the best ATM teams in the world and we had a product that was outstanding compared with all the other switches on the market.’2

With others developing similar technology, Virata staked its competitive advantage on its ability to enhance the software functionality of its ATM products. Unfortunately, however, by late 1995 it was clear that, in the words of Virata’s Vice-president of Marketing, Tom Cooper, ‘The dog was not eating the dog food – not just Virata’s brand, no one’s brand.’ As one of Cooper’s former colleagues from Hewlett-Packard pointed out, ‘Tom, your problem is that you have a technology in search of a problem. No one has a problem yet!’3 Tom’s former colleague was right. The vast majority of traffic over LANs was data, not voice or video. Multimedia networking simply wasn’t a mainstream application just yet.

But an absence of a real customer need was only part of the problem. Companies like 3Com, whose livelihoods were invested in Ethernet technology, were not about to let some upstart technology eat their lunch. These companies had deep pockets and large numbers of customers who had made significant investments in Ethernet networks.

These customers were happy to pay for upgrades and enhancements as further developments in Ethernet technology occurred. Even though Virata’s ATM switches ran at more than twice the speed of Ethernet switches – at twice the price – customers just were not buying. ‘It was the classic better mousetrap phenomenon,’ said Cooper.4 The better mousetrap, however, is not always the one that sells.

By 1996, morale at Virata was heading south. Virata’s CEO tried to rally his troops, arguing that Virata was just slightly too early with its technology. He believed that, ‘When this market takes off, Virata will be a leading player and will ride on its successes far into the future.’5 Fortunately, there was continued faith among investors that ATM was a technology for the future. After all, ATM was a better mousetrap. As a result, Virata obtained another round of $13 million in June: $3 million from the original investors and $10 million from Oracle, whose CEO Larry Ellison had invested in another of Hauser’s companies some years earlier. Ellison had faith in Hauser and it took only a 30-minute meeting to seal the deal.

Stay the course or change direction?

With a fresh injection of cash in hand, Virata renewed its efforts to sell its line of network products. Significantly, and as a result of connections built earlier in his career, Tom Cooper had had some success in licensing the software and semiconductors used in Virata’s LAN equipment to companies interested in Virata’s technology for applications in quite different areas. One recent approach had come from Alcatel, a French communications equipment company.

Alcatel was pioneering asynchronous digital subscriber line (ADSL) technology, which it thought might make possible the upgrading of old-fashioned twisted-pair copper telephone wires to handle the growing interest in broadband applications. Alcatel wanted to use Virata’s ATM LAN products as part of its ADSL demonstration, license the technology, and perhaps build it into its own hardware devices. These devices would handle high-speed data in the so-called local loop – the ‘last mile’ of copper that reached from telephone companies’ facilities to their subscribers’ homes and premises. As we saw in Chapter 4, the market for high-speed data applications like DSLs looked promising even in 1996, and Virata’s technology was worth a look, Alcatel thought.

Some at Virata were intrigued with the forecasts of rapid growth of online ADSL subscribers and wondered whether this market might be a more attractive one than the LAN markets Virata had been pursuing. But Virata’s CEO would have none of this thinking: ‘It would be disastrous to divert our attention to the licensing market as you suggest.’6 The company soon found itself split into two camps and, barely one month after Virata received Ellison’s cash, the CEO left the company.

In the summer of 1996, the Virata board asked Charles Cotton, the General Manager of the Cambridge operation since mid-1995, to become COO and acting CEO. Cotton’s charge was to determine which direction Virata should take in the short term. Pulling his team together for a late summer strategic retreat in California’s Napa Valley and fuelled by the California sunshine – and some of the world’s finest wines – Virata management decided to pursue both directions concurrently, at least for the time being. It was too early to know whether the licensing strategy – or DSLs themselves, for that matter – would bear fruit, and it remained unclear whether the networking market might turn profitable. Although networking sales had grown to nearly $1.5 million per quarter, the direct selling and distribution costs exceeded the gross margin. Virata was burning cash rapidly and more would be needed soon.

That same month, Alcatel won a large contract with four regional Bell operating companies in the USA to deploy its DSL architecture. This broad-based deal covering a significant portion of the American telecom terrain focused the market on ATM-based ADSL solutions. At last, there was a light at the end of Virata’s tunnel. In 1997, Virata licensed its technology to other telecom suppliers and to Com21Corporation, a leader in bringing high-speed data capability to American and European cable television operators, who also saw the potential for an ATM-based solution for their applications. Notwithstanding these deals, Virata’s licensing revenues were still very small.

As the company pursued both the licensing strategy and the networking market, the Virata team remained badly divided. A new CEO – the third in just 15 months – was convinced that networking products – not DSLs – were the bread and butter of Virata’s future. The licensing business was just too different and required different skills. Licensing deals were sold to original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) that would add Virata’s software technology and chips to their own products. Sales cycles were certain to be long and there was no assurance that the extensive selling effort required would actually result in purchase orders. The licensing business would also hitch Virata to the DSL wagon, and it was by no means clear that DSLs would win the battle against other competing technologies.

Cotton and Cooper, however, were of the mind that Ethernet was going to win the battles and the war for networks, and that ATM – Virata’s better mousetrap – would lose. Licensing looked to them like the better bet. The debates over Virata’s direction became increasingly divisive, and in September 1997, after only five months at the helm, the new CEO departed and Cotton was promoted into the position. As he saw it, the two-pronged strategy was no longer tenable: ‘We were straddling a chasm that was starting to widen. Sooner or later we had to jump to one side, otherwise we risked falling into the chasm never to recover.’7 His first move was to dismiss Virata’s entire networking product sales staff. The house would be bet on DSLs.

The new direction required Virata to develop new capabilities in chip design. It also meant that Virata’s customer base would shrink sharply in number, as it focused its efforts on large OEMs. By 1998, three customers accounted for 40 per cent of Virata’s revenues, and its total customer base numbered less than 20. The long sales cycle also meant that Virata’s cash continued to burn.

A happy ending

Fortunately, there was not a day that passed in 1998 when someone wasn’t reporting the red-hot growth of the Internet and its follow-on effect for broadband access. The Internet frenzy enabled Virata to raise, with the help of Index Securities, a Swiss investment bank, another $31 million from existing and new investors to fund the company until a planned public offering in 1999. In November 1999, with Virata showing growth in the licensing business – no profits just yet, however, but declining losses – Virata shares started trading at $14 on NASDAQ and jumped to $27 by the end of the first day. Broadband access and the Internet were hot. Virata’s technology was playing a key role, and technology investors wanted to get on board. By early 2000, Virata’s share price reached $100.

In the year after its IPO, in an effort to broaden its market and its technology base, Virata made four acquisitions. In doing so, it soon became evident that Virata was headed for a competitive collision with Globespan, an American fabless semiconductor company with a similar strategy. In December 2001, the two companies merged to create the world’s leading provider of integrated circuits, software and systems designs for DSL providers.8

What endowed Virata’s long struggle with its happy ending? To be sure, the coming of the Internet age had a lot to do with it. Hermann Hauser’s ability to raise a sorely needed $10 million from Larry Ellison in a 30-minute meeting didn’t hurt either. But, as Hauser recalled, ‘Without a doubt, the thing that carried us through was the quality of the team and all of its connections.’ When Cooper told the story about Alcatel’s interest in the Virata technology at a board meeting, ‘The board seized upon the story and talked to some people that they knew. It turned out that the board had spotted an early trend, and this is where we made all of our money.’9

Virata’s connections mattered. Call it luck or serendipity if you like. But Tom Cooper’s connections down the value chain to potential customers in markets not then being served led to the Alcatel enquiry. The board’s connections up and across the value chain – to suppliers and other players in related industries who could confirm what was happening with DSLs – enabled Virata to place a very risky bet with more confidence than would otherwise have been possible. It’s been said that lady luck comes to the well-prepared. As we’ve now seen, she also comes to the well-connected.

Digital Equipment Corporation: missing the boat10

‘Customers don’t want a computer that sits on a desk. Customers want computers that sit on the floor.’11 That’s what Ken Olsen, co-founder of Digital Equipment Corp (DEC), said in a speech in the late 1970s. Most of us, of course, now have computers on our desks and others in our hands or laps or glued to our ears, with processing power that surpasses DEC’s computers that sat on floors at that time. And DEC itself and most DEC computers are long gone, having been replaced in the 1980s and 1990s by PCs and servers from the likes of Dell, HP and Sun.

DEC founders Ken Olsen and Harlan Anderson set out in the late 1950s to provide functionality similar to large mainframe computers – mostly IBMs, in those days – but in a smaller, more bare-bones machine. In 1959, the company came out with its first computer – the Programmed Data Processor (PDP-1). Olsen described this computer as a console ‘with all the instru- ments and lights, very much like you see in a power plant’.12 The PDP-1 cost the customer $125,000–$150,000. By 1965, DEC had sales of $6.5 million, with profits of $807,000.

In 1966, DEC started selling the PDP-8. While considerably less expensive than its predecessor, each of these machines still sold for $18,000. DEC marketed the PDP-8, with its high-quality video display terminal, to businesses, universities, newspaper offices and publishers. It was also a particularly attractive computer for third parties who bought the PDP-8 machine from DEC, customized the hardware and software to meet the needs of their customers, and sold the enhanced computer as their own product. DEC’s third-party business soon accounted for 50 per cent of its sales. By 1970, DEC was the most successful minicomputer manufacturer in the world.

Through the early 1970s, DEC remained a leader in the minicomputer industry. Olsen said, ‘For many years we made the same two computers, the PDP-8 and the PDP-11. We kept that design consistently so that software the customers wrote would continue to work on newer models and the software we wrote would continue to work and get more and more robust.’13

Quite deliberately, rather than join the competition for the PC market as it emerged in the late 1970s, DEC avoided it and concentrated on networking issues: ‘We made some PCs designed to be part of the networking but the general PC market was not for us. There were too many people in it . . . You could build them in your basement. That was not for us.’14 The VAX was DEC’s product line that offered networking capability. It connected several minicomputers in a LAN. One of the company’s most popular networking products, the VAX 8600, allowed a system of minicomputers to function like a mainframe. But targeting the mainframe market, with its sales trend heading south, flew in the face of the rapid growth in the capability of PCs.

Finally, in 1980, DEC did begin developing personal computers, but Olsen insisted that the new machine be called an ‘application terminal and small system’ rather than a PC.15 ‘We believe in PCs. We encourage them. We network them. We use them in large numbers. But we still believe that most people in an organization want terminals. With terminals you don’t have to worry about data management, you don’t have to worry about floppy disks. You just sit down and it does the work for you automatically.’16

DEC’s late decision to enter the PC market, and to enter with three different product lines (Rainbow, Pro and DECmate), proved both confusing and damaging. In 1984, the effects began to show. In the third quarter of that year, earnings were down 72 per cent from the previous year. And that was only the beginning.

In 1988, Sun Microsystems introduced computers that ran the UNIX operating system. Hewlett-Packard soon followed with its own UNIX-based Apollo computers. All these systems had far more computing power than DEC’s minicomputers and were much less expensive. Moreover, they ran on UNIX, which was rapidly becoming the de facto standard in operating systems, thereby encouraging third parties to write innovative software that would run on these platforms. Ironically, much of the UNIX software was developed on DEC machines. DEC, however, had been doing so well with its proprietary VMS operating system that it gave its UNIX offering little support. As UNIX took hold, no longer were DEC’s minicomputers, with their proprietary operating system, the best alternative. They were no longer in the race.

By the dawn of the 1990s, DEC found itself in dire trouble. Tens of thou- sands of employees’ jobs were lost. By 1994 DEC, once 126,000 people strong, was a company of only 63,000. Finally in 1998, DEC, by then no longer a computer maker, was sold to Compaq.

What did DEC miss?

There were many things that DEC did right in its heyday. It fared well for a quarter of a century – a veritable eternity in any high-tech industry. And, while it did post some impressive financial results along the way, it was plagued repeatedly by an inability to stay in front of the technology curve, missing the mark on some sweeping trends.

In the late 1960s, a group of DEC engineers led by Ed de Castro was assigned the task of designing a 16-bit computer that would replace the then-current 8-bit technology. Their final plan contained a basic 16-bit system that could be grown to 32 bits as well as a series of compatible products that would allow users to upgrade their existing machines rather than replace them. But what de Castro’s group was suggesting amounted to scrapping the entire DEC product line and replacing it with the new 16-bit machines. DEC’s management soundly rejected it. So in April 1968, de Castro and two other engineers left DEC, raised their own venture capital and started their own company, Data General Corporation, to produce 32-bit computers. By 1969, Data General was one of the hottest new companies in minicomputer manufacturing, tapping a market that could have been DEC’s.

Then in 1972, a DEC team working on the PDP-11 recommended that DEC develop a product that combined a computer (the PDP-11/20) with a terminal and a printer. According to the PDP-11 group, this ‘Datacenter’ would appeal to a broad market of individual users, including scientists, technicians and others in administrative positions. DEC’s leadership rejected this individual computer idea. Had DEC pursued the datacenter, could it have been the PC pioneer? We’ll never know.

By 1980, with Apple and other personal computers beginning to make waves, and a year before IBM’s PC introduction, DEC’s product managers, those individuals who face the customer, suggested that DEC begin to play in the personal computer space. Olsen and his team refused. The rest is history.

Why?

Why did DEC repeatedly miss key changes in its marketplace? It’s difficult to know with certainty without having been in DEC’s meetings or inside Ken Olsen’s head. The contrast with Virata, however, is striking. Virata had extensive connections up, down and across its value chain. When Virata got new information, it fanned out its other connections to help it interpret what it had heard. DEC, too, may have had some of these connections, but if it did, its top management wasn’t very good at listening to them or leveraging other connections to take advantage of the information those connections provided. DEC leadership, like the ostrich, had its head in the sand.

The vibrancy of DEC’s connections was perhaps encumbered by DEC’s focus on and belief in its own technology and its faith that its solutions were superior to others. ‘They believed [their] operating system was simply the best and would remain so into the new millennium,’ said Jean Micol, a former DEC marketing executive.17 If this is the case, why bother to develop connections for keeping track of external developments? Call it corporate arrogance or simply naïveté. DEC missed 16-bit computing. It missed PCs – not once, but twice! It missed UNIX. And now DEC is gone.

Markets and industries do change – especially high-tech ones. Success in changing markets requires well-developed connections to keep abreast of the changes, and it requires a top management team that’s open-minded enough to consider changing course when conditions so indicate. Had Olsen spent time talking to and building a wider set of informational relationships – with DEC’s sales channel and distributors, with its OEM manufacturers, even with its own marketing department – then he would have heard the resounding push towards PCs in the early 1980s and towards UNIX in the late 1980s. Hindsight suggests that the DEC team simply wasn’t up to this task. Are you?

What investors want to know

Connections up, down and across the value chain are important to investors for a variety of reasons. In the short term, your connections with potential customers, especially large or strategically significant ones, enhance the likelihood that your new venture will meet its revenue targets. Connections up the value chain – with suppliers – enhance the likelihood that your new venture will be able to obtain the inputs it needs at favourable costs and on favourable terms. Connections across your industry and across potential substitute industries will enhance your understanding of the competitive situation that your venture will face, helping you differentiate and position your products in ways that will stand apart from those of your competitors. These short-run roles are important, and investors will want to know how your team measures up on such connections.

In the long term, however, the value of connections like these is more subtle, perhaps, but extremely important, especially in the highly uncertain and changing markets where many entrepreneurial ventures play. Investors know from experience that most of the money they’ve made has been made from plan B, not from plan A. ‘Surprises are not deviations from the path. Instead they are the norm, the flora and fauna of the [entrepreneurial] landscape, from which one learns to forge a path through the jungle’, says Saras Sarasvathy,18 based on her research into entrepreneurial decision-making. But there’s a problem here, because when an investor decides to invest in your venture, they do not really know what plan B will look like. How can investors insure themselves against the risk that your plan A will not work and that you might not come up with a suitable plan B? The best answer? Your and your team’s connections.

Without such connections, you may not have the market and competitive information that you’ll need to revise your strategy when the need arises, as Virata was able to do at a crucial juncture but as DEC was not. You may not be able to take advantage of a favourable change in market needs that could benefit your venture substantially. You may not have the ability to judge quickly – and quickly may be important – which of several alternatives to a failing plan A ought to be your plan B. Whether your venture gets started on lean principles – where attention to the need for pivoting is top of your mind – or otherwise, these are crucial investor concerns that will influence their view of the attractiveness of your opportunity and your entrepreneurial team, because they reduce the risk that your venture will fail. These concerns should be of similar concern to you.

Lessons learned

The fact that connections matter will not surprise any astute entrepreneur. But some of the ways they matter, in both the short and long run, are issues to which many entrepreneurs give little thought. What can we learn from the Virata and DEC stories to help you assess your opportunity?

Lessons learned from Virata

Virata was fortunate that a confluence of technological trends created a market – telecom providers seeking to provide dial-up broadband access to their telephone customers – for which its technology happened to be extremely well suited. It’s been said many times that luck can play an important role in entrepreneurial success. Being in the right place at the right time, as Virata was, can turn a struggling company into a blockbuster.

The lesson from Virata isn’t, however, about luck. The lesson is that connec- tions – the right kind of connections – can deliver to an entrepreneurial firm three important outcomes:

- identifying fortuitous trends, new information or changes in the marketplace that the company might take advantage of;

- doing so early, before other would-be competitors can do so;

- obtaining a broad-based assessment of such a development, from a variety of perspectives outside the firm, in order that a decision to pursue it can be an evidence-based one rather than a risky guess.

With connections that deliver outcomes like these, your pivots are more likely to be grounded in evidence, which in turn helps you and your investors get comfortable with the change in strategy that the pivot entails.

What kind of connections will your venture want to have?

- Connections up the value chain to suppliers who deal with the leaders in your industry and with firms in other industries that might serve as substitutes for the products you provide.

- Connections down the value chain to potential customers – including distributors, consumers, and users – in target markets that you might serve one day in addition to the markets you plan to target at the outset.

- Connections across your industry with competitors – and with firms from other industries that offer substitutes – so that you can gain some perspective to gauge accurately changes in market conditions. When your sales increase, it’s good to know if they are doing so because you are gaining market share or if you are simply benefiting from a rising tide that floats all boats. The same is true when your sales are soft.

Connections across your industry also help you understand its CSFs, an important issue in helping you assemble an entrepreneurial team that can deliver the kind of performance you and your investors seek. These connections can also identify and build relationships with skilled people who know your industry and whom – now or later – you may wish to attract to your company.

Lessons learned from DEC

As we have seen, DEC failed to adapt to trend after trend in the computing industry: 16-bit computing, the rise of PCs and UNIX. The problem for DEC was not that they had no connections or that no one in DEC saw these things happening. Indeed, some did. Of the three outcomes listed above that the right kind of connections can deliver for an entrepreneurial firm, DEC’s difficulties seemed to be with the third issue, i.e. obtaining a broad-based assessment of these developments from a variety of perspectives outside the firm. As a result, DEC’s decisions not to pursue these developments in a timely and aggressive manner appeared to have been based on DEC’s blind faith in its own products and solutions – arrogantly and naïvely, some would say – rather than on the basis of the marketplace evidence that was there to be seen and understood.

An inward-looking culture, especially in a rapidly changing industry like computing, adds additional risk to what we’ve seen is an always-risky game of entrepreneurship. As Andy Grove,19 long-time CEO of Intel, wrote, ‘only the paranoid survive’. The same is true for those assessing new opportu- nities. Yes, this means you. Being inward-looking, focused on your idea rather than on the market and industry where it might take root, and focused on building the right team to help you achieve your dreams, is a pathway to impending disaster. Having a broad set of the right kinds of connections – who you and your team know – does matter, not only in running your business once it starts, but much earlier as well, in assessing and shaping your opportunity as it evolves. Don’t go too far without them. Entrepreneurial success is not just about what you know. It’s about who you know and your ability to use your network productively.

The new business road test: stage seven – the connectedness test

- Who do you and your team know up the value chain in the companies that are likely suppliers to your proposed business and to your competitors? In suppliers to companies in other industries that offer substitute products for yours? Be sure you have names, titles and contact info.

- Who do you and your team know down the value chain among distributors and customers you will target, both today and tomorrow? Names, titles and contact info, please.

- Who do you and your team know across the value chain among your competitors and substitutes? Names, titles and contact info, please.

- Where are any key gaps in your teams’ connections (to be added to your risk list), and how can you fill them?

Open your The New Business Road Test app and you’ll find the above checklist. You might want to begin this stage of your road test by using the app to record an initial conclusion about just how connected you are – or are not – to others whose information may help you pivot appropriately if necessary. The app provides a place to record that assessment, along with places to keep track of the new connections you make, organized into four categories: prospective suppliers, prospective customers or channel members, prospective consumers or end-users, and prospective competitors in the industry in which you plan to compete or in substitute industries.