Case 16. Ethical Product Sourcing in the Starbucks Coffee Supply Chain

† Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, USA; [email protected]

Introduction

Fair Trade is a movement that “seeks to empower family farmers and workers around the world while enriching the lives of those struggling in poverty.”1 Fair Trade is based on the principal of paying above the market rate for goods that are environmentally friendly and made by workers in safe conditions who are paid a livable wage. Coffee is a significant focus of the Fair Trade movement, because coffee trails only oil in global trade volume.2 Despite high global demand, market price fluctuations can create hardships for many of coffee’s small producers. In the United States, the coffee market is estimated to be over $32 billion,3 with Starbucks being the dominant coffee retailer. With its large market presence, Starbucks has been under pressure to increase the amount of Fair Trade coffee it imports. However, doing so has drastic implications for Starbucks’ supply chain as Fair Trade coffee is, by design, more expensive than similar goods. Moving forward, Starbucks must decide whether the ethical mission of Fair Trade coffee warrants the increased procurement costs.

1 Fair Trade USA. (2010). About fair trade usa. Retrieved from www.fairtradeusa.org.

2 Global Exchange. (2011). Coffee in the global economy. Retrieved from www.globalexchange.com.

3 Specialty Coffee Association of America. (2012). Coffee facts and figures. Retrieved from www.scaa.org.

Overview of Fair Trade

Fair Trade began in the 1940s as a small collection of European and North American organizations that focused on aiding marginalized producers by providing a market to sell basic crafts and goods.4 These small organizations focused their efforts on importing crafts from countries such as Angola and Nicaragua. In the 1960s, “alternative trade organizations” such as Oxfam formed in Europe and started distributing imported products through a variety of small “worldshops.” The movement sought to alleviate poverty among distressed populations that some considered to have resulted from growing globalization and trade imbalances.

4 FairtradeUSA. (2010). History. In Fair Trade USA. Retrieved 9/24/2012, from http://www.fairtradeusa.org/what-is-fair-trade/history.

Because sales were confined to small retail outlets and ordering through select publications such as the Whole Earth Catalog, sales growth was severely limited due to a lack of market presence. In order to expand distribution, retailers required a system that enabled consumers to identify a product as ethically sourced no matter where the product was sold. To solve this problem, the Fair Trade label was developed in 1988, giving products a recognizable symbol allowing fair trade goods to be readily identified as fair trade. Fair trade began to be offered in large retailers and grocery stores, spurring a growth in sales that reached an estimated $3 billion by 2007.5 In 1997, various Fair Trade labeling groups were combined to form the Fairtrade Labeling Organization.

5 Rando, L. (2008, May 23). Worldwide fairtrade sales up 4 percent. Confectionary News. Retrieved from www.confectionarynews.com.

Despite the original focus on crafted products, the declining demand for handicrafts in 1980 prompted a shift toward agricultural goods. Initially, coffee was the major commodity offered through Fair Trade, but it has since expanded to include other products such as tea, almonds, bananas, and olive oil. Coffee was a natural target for Fair Trade groups, as it is one of the few remaining international commodities that are still produced in small estates. Prior to 1973, strict quota agreements were in place among producing countries that helped stabilize prices and keep producer margins high. The collapse of regulation in 1973 resulted in the swift entry of new growers from regions such as Vietnam. The additional production of beans caused a drop in coffee prices to record lows and severely impacted the economic livelihood of producers.

In response, Fair Trade organizations partnered with producers in an effort to protect them from uncertain swings in global coffee prices. To promote economic well-being, the fair trade system uses two mechanisms. First, coffee purchasers agree to pay a minimum price for Fair Trade produced coffee. As of 2012, this minimum is set at $1.25 per pound. This creates economic stability as producers can be assured of a guaranteed price despite swings in global markets. If global prices for coffee increase above the $1.25 minimum, purchasers agree to pay a $0.10 premium. Exhibit 16-1 illustrates the price differences between Non-Fair Trade and Fair Trade coffee from 1989–2007.

Reprinted with the permission of the Fairtrade Foundation.

Notes: NB Fairtrade Price = Fairtrade Minimum Price* of 140 cents/lb + 20 cents/lb Fairtrade Premium**

* Fairtrade Minimum Price was increased on 1 June 2008 & 1 April 2011.

** Fairtrade Premium was increased on 1 June 2007 & 1 April 2011.

The New York price is the daily settlement price of the 2nd position Coffee C Futures contract at ICE Futures U.S.

When the New York price is 140 cents or above, the Fairtrade Price = New York price + 20 cents

Exhibit 16-1. The Arabica coffee market 1989–2013: Comparison of Fairtrade and New York prices.

To be certified as a Fair Trade producer, farmers need to comply with an extensive list of production criteria, including using environmentally friendly pest control measures, enhanced storage procedures for chemicals and fertilizers, strict waste management practices, and the avoidance of genetically modified (GM) seeds for growing. For labor, Fair Trade producers are required to supply adequate personal protective equipment, prevent child labor, avoid discrimination, and provide a healthy working environment by maintaining sanitary conditions. In addition, a portion of the Fair Trade premium received by producers must be invested in the local community.6

6 Fairtrade International. (2011). Fairtrade Standards for Small Producer Organizations. Bonn: Fairtrade International.

The Fair Trade Supply Chain

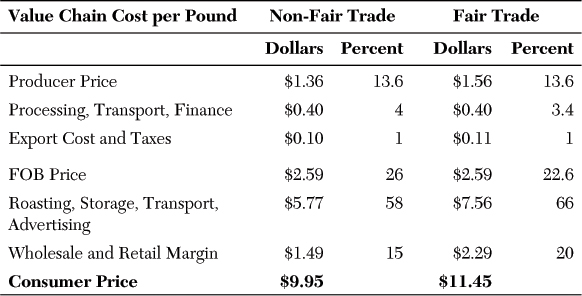

Typical coffee production occurs on small, mostly family-owned farms, with an average size of about 2 hectares (5 acres).7 Due to a climate favorable for coffee growing, most farming occurs in countries near the equator, with a majority of world production occurring in Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, and India.8 Coffee beans must be picked by hand; therefore, harvesting is a labor-intensive process. The ideal time to harvest coffee beans occurs when the beans have ripened into a bright red “cherry”; however, ripening times vary among plants, leading some farmers to harvest both ripe and unripe cherries at the same time. This, and other elements such as growing conditions, can create quality variations among producers. After harvesting, the coffee cherries are dried and hulled, then separated by hand to be packaged. Bulk cherries are then typically sold to a local distributor who then transports the beans to a port for export. While some producers may roast the beans prior to export, many retailers such as Starbucks and Green Mountain Coffee conduct their own roasting operations. After roasting, the prepared coffee beans are shipped to retail outlets for preparation in beverages or to be sold in bulk directly to the consumer. Table 16-1 details estimated supply chain prices for a simplified coffee value chain.

7 Calo, M. and Wise, T. (2005). Revaluing Peasant Coffee Production. Global Development and Environment Institute.

8 National Geographic. (n.d.). Major Coffee Producers. Retrieved from www.nationalgeographic.com.

Table 16-1. Estimated Costs per Pound for the Coffee Value Chain

Notes: Non-Fair Trade and Fair Trade prices estimated from the average prices of all coffee ‘C’ futures in 2011. Transportation prices assumed to be equal for both commodities. Wholesale and retail margins for non-Fair Trade and Fair Trade assumed to be 10% and 15% respectively.9

9 Daviron, B., & Ponte, S. (2005). The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development. New York: Zed Books.

Consumer price obtained from www.starbucks.com.

Of note are the higher advertising costs incurred by Fair Trade retailers vs. their conventional counterparts. The success of an eco-labeling campaign rests on the ability of an organization to educate and promote products to consumers.10 Therefore, retailers incur additional expenses in an effort to inform the public about the virtues of Fair Trade.

10 Rafi-USA. (n.d.). Greener fields: signposts of successful eco-labels. Retrieved from www.rafiusa.org.

Criticism of Fair Trade

Despite the good intentions of Fair Trade, some have criticized the value of Fair Trade in promoting the economic livelihood of small farmers. The premium is pushed onto the consumer. Fair trade goods, on average, are priced 10–15% higher than other goods.11 While consumers may be willing to pay the higher price under the assumption that the additional cost represents a charitable contribution, some evidence suggests that as little as 10% of the price premium actually reaches producers, while retailers pocket the rest.12

11 Stecklow, S., & White, E. (2004, June 08). What price virtue?. The Wall Street Journal.

12 Voting with your trolley. (2006, December 07). The Economist, 381(8507), 73-75.

Another problem resides in consumer demand for Fair Trade coffee. In 2011, over 6.1 million metric tons of Fair Trade coffee were exported (approximately 13.5 billion pounds),13 yet global supply far exceeded demand. For example, one Fair Trade certified producer in Guatemala reported being able to sell only 26% of its production on the Fair Trade market.14 In these instances, farmers are forced to sell their goods to non-Fair Trade importers. Further, critics contend that Fair Trade has watered down certification standards in order to push lucrative licensing fees—fees that amounted to $6.7 million in 2010.15 The reduction in quality, some argue, is reducing consumer confidence in Fair Trade products.16

13 Fairtrade Foundation. (2011). Fairtrade foundation commodity briefing. Retrieved from Fairtrade Foundation website: www.fairtrade.org.uk.

14 Berndt, C. E. H. (2007). Does fair trade coffee help the poor?. Fairfax, VA: Mercatus Center.

15 Neuman, W. (2011, November 23). A question of fairness. The New York Times, p. B1.

16 Haight, C. (2011). The problem with fairtrade coffee. Stanford social innovation review, Summer, 74-79.

Starbuck’s Fair Trade Policy

With over 19,972 stores in 60 countries, Starbucks is the world’s largest coffee retailer. It is estimated that in fiscal 2011, Starbucks sold close to 4 billion cups of coffee, which translates to 428 million pounds of coffee purchased from producers.17 Starbucks, as part of its broader responsibility initiatives, has adopted a series of ethical sourcing principles.

17 Volkman, E. (2012, August 25). As coffee bean prices fall, which coffee stocks are the winners? The Motley Fool. Retrieved from www.fool.com.

According to Ann Burkhart, global responsibility manager at Starbucks, “Helping farmers thrive in the midst of a changing climate is fundamental to our mission statement and helps to secure the future of the thing we are most passionate about: incredible coffee.”

In line with that mission, about 8% (approx. 34 million pounds) of Starbucks’ coffee is certified as Fair Trade. In addition, Starbucks has created its own ethical sourcing guidelines called Coffee and Farmer Equity (CAFE).18 Working with Conservation International, Starbucks has developed a series of certification standards, separate from Fair Trade, that seek to promote economic accountability, social responsibility, and environmental leadership. According to Starbucks, about 86% of all its purchased coffee complies with CAFE standards, with the goal of 100% compliance by 2015. Through the development of its own compliance criteria, Starbucks gains the ability to source from qualified but non-Fair Trade suppliers.

18 Starbucks Co. (n.d.). Responsibly grown coffee. Retrieved from www.starbucks.com.

Calls for Greater Participation

In 2008, various consumer groups began pressuring Starbucks to increase the amount of Fair Trade certified coffee offered in its U.S. stores.19, 20 Activists contend that since 100% of Starbucks’ UK coffee is Fair Trade certified, the U.S. market is lagging. Starbucks responded by doubling their U.S. Fair Trade coffee imports to 40 million pounds in 2009 and stating that its U.S. imports are tailored to meet available demand.

19 Organic Consumers. (n.d.). Fairtrade vs. starbucks. Retrieved from www.organicconsumers.org.

20 O’Brien, C. (n.d.). Starbucks: Fair trade or “tradewash”?. Retrieved from www.beanactivist.com.

Despite calls for greater participation in Fair Trade, Starbucks has pursued its own certification system, citing a lack of quality control standards with Fair Trade coffee. However, Starbucks’ corporate policies are effectively self-policing, with no third-party certification to verify its sourcing claims.21 This leaves open the possibility of “greenwashing,” whereby products are marketed as ethical yet in reality do not live up to consumer expectations of responsibility. An example of this occurred in 2006 when Starbucks began selling an exclusive Black Apron brand sourced from Ethiopia’s Gemadro Estate. Starbucks claimed that the coffee was produced in accordance to the highest standards of sustainability. However, it was soon discovered that Gemadro Estate’s expansion efforts contributed toward the destruction of forests and vegetation as well as threatening wildlife habitats. Additionally, Gemadro Estate was found to be part of a conglomerate that owns a variety of gold mines, oil companies, and factories.22

21 Jaffee, D. Weak coffee: certification and co-optation in the Fair Trade movement. 2012. Social Problems 59, 1. 94–116.

22 Coffee Habitat. (2006). Starbucks ethiopia gemadro estate: corporate greenwashing?. Retrieved from www.coffeehabitat.com.

Moving forward, Ann Burkhart and the Corporate Responsibility team at Starbucks must decide how to pursue the company’s ethical sourcing policies. Should Starbucks continue investing in its own standards that may face skepticism from the public? Or should Starbucks commit to sourcing more coffee from Fair Trade certified producers while running the risk that consumer demand will not keep up with supply?