CHAPTER 1

What Is Talent Leadership?

In today’s global economy, it is critically important that organizations optimize their investment in human capital. Only the human capital asset can provide an organization with any real hope for meaningful market differentiation, positive branding, superior execution, and ultimate operating success. Business strategies that are overly weighted toward developing new technologies or cost controls—for example, without the proper weighting of the human capital assets required to execute strategy—will result in a disastrous, short-lived plan that will lead to doom. All assets, except the human capital asset, eventually become commodities. Beyond this, a host of external factors—an aging baby boomer population, job market instability, declining birthrates, and worker “migration”—are combining to make it extremely challenging for organizations to optimize their investment in human capital. For most organizations, it is just plain difficult to find and keep good talent. Shifting world demographics, the aging workforce, and global mobility, as well as a myriad of internal challenges (i.e., limited resources, skill gaps, insufficient leadership skills, etc.) are forcing organizations to rethink their human capital management strategy. Talent shortages at the leader level are exacting a heavy toll on growth and costs. Some organizations are literally sitting on capital, unable to expand into new markets or make critical acquisitions, due to a lack of leadership talent. Other organizations are spending millions on recruitment as they scramble to fill key positions. The cost of training new managers and executives is equally taxing. Of greatest concern are the costs of poor decision making as organizations are forced to place less qualified individuals into leadership positions. Poor leadership can translate into millions in lost profits and missed opportunities.

The Search for Solutions

What can be done to reverse these trends? Clearly, organizations need outstanding high-potential identification and development programs. Every process from succession planning to leadership development must be world-class. The market is too competitive for anything less. More than anything else, however, an organization’s ability to successfully reverse these trends is in direct proportion to the health and vibrancy of their talent management systems, that is, the four D’s:

• Deployment—selecting and promoting talent

• Diagnosis—continuously assessing leader, individual contributor, and team capability

• Development—continuously developing leader, individual contributor, and team capability

• Demarcation—differentiating and rewarding performance

None of this will occur, however, unless organizations and their leaders demonstrate talent leadership. Specifically:

• Organizations (and their leaders) must believe that the human capital asset is the most critical variable in driving operating excellence. Everyone must be enlisted, coached, and cajoled (if needed) in support of this belief.

• Organizations and their leaders encounter numerous challenges—external and internal—that are tied to the four D’s. If unresolved, these challenges will exact a significant toll on the health and vibrancy of an organization’s performance.

• Clear, convincing, and powerful relationships exist between an organization’s operating results and the relative strength of their four D’s. Top-performing firms and their leaders understand, respect, and act on these relationships.

• There are also clear and proven predictive relationships between certain human capital Leading Indicators and their impact on individual and team performance as well as operating results. Likewise, the top firms and leaders understand, respect, and act on these relationships.

• The foundation for continuously improving these Leading Indicators consists of assessment and calibration. Organizations that excel in selecting, promoting, and developing talent will rigorously and passionately assess Leading Indicators. Assessments geared to leaders, individual contributors, and teams enable calibration and recalibration on the Leading Indicators so that they can course-correct and improve their ability to predict and realize operating success.

Elements of a Winning Human Capital Mindset

At the core of creating a winning mindset and strategy is a core belief: Accurate information drives effective strategies. This is good news for most organizations because they already have a great appreciation for accurate information. Operating metrics, financial ratios, and a variety of other analytic tools receive intense attention by boards and senior leadership. Unfortunately, most of these metrics are lagging indicators—after-the-fact metrics that tell a story of what happened (e.g., cost per hire and turnover). They are important because they can lead to course correction as the organization strategizes for the future; however, they are not as important as Leading Indicators—like leader capability and quality of hire/promotion—which are proven predictors of operating results. Early measurement of Leading Indicators enables an organization to course-correct much earlier if necessary to ensure operating goals are met.

Being accurate (only as a result of assessment) must begin with the end in mind. Organizations and their leaders need to define the desired future state along with the competencies required to execute both the current and future strategy. Organizations that excel in human capital/talent management practices are passionately and diligently focused on operational targets as well as the knowledge, skills, and abilities (i.e., competencies) required to meet those targets for every position—CEO, senior leaders, leaders, managers, individual contributors, and teams. And that’s just the beginning. From there, it is critical to be calibrated on the competencies that both incumbents (from CEO to individual contributor) and external candidates possess (only as a result of assessment). Ultimately, only accurate targets and talent/team diagnostics enable an organization to make the best selection and promotion decisions, training decisions, succession planning decisions, and reward decisions.

All assessment—whether directed at isolating competencies, determining CEO and senior leader readiness, determining potential, or determining team effectiveness and engagement levels—needs to be focused on providing better information, that is, Leading Indicator information, as a basis for improved decision making. Not unlike the field of medicine, in the field of talent management, it is not too far from the truth to state, “Prescription before diagnosis is malpractice.” If leaders can lead their managers and teams on a rewarding journey—characterized by a passionate and diligent focus on assessment and the power that assessment information yields—such a journey will provide a solid foundation for other critical beliefs and practices to emerge. These beliefs and practices are shared by organizations with superior human capital/talent management processes:

• Better talent = competitive advantage.

• The human capital mindset is the catalyst for action.

• Strengthening the talent pool is every leader’s job.

• The talent gold standard has been established (by means of role modeling).

• Leaders must be held accountable for identifying and developing talent.

• Real money must be invested in talent management.

• Talent review processes, including the C-suite, are critical.

All of these beliefs should be the catalyst for action—positive action. According to McKinsey’s War for Talent Research, however, the actual percentage of organizations engaged in positive human capital practices is very startling—and is easily traceable to a relatively weak human capital mindset and poor execution. Here are the percentages of senior leaders who strongly agreed their own organization did the following:

| • Attracts talented people | 19 percent |

| • Develops talent | 3 percent |

| • Retains talent | 8 percent |

| • Removes poor performers | 3 percent |

| • Knows the A, B, and C players | 16 percent |

External and Internal Challenges

Aging baby boomers, declining birthrates, and volatility in the job market are combining to raise the stakes in the human capital market. Global competition for talent, especially leadership talent, is intense. Leadership shortages are more pronounced in growing markets such as India and China. Finding leaders in these markets with experience in Western corporate culture is proving difficult, with many organizations competing for the same small population of individuals. On the flip side, finding U.S. leaders with global experience is proving almost as challenging. In one recent study conducted by Executive Development Associates, globalization was rated fourth as a cause for today’s leadership shortages. The first? A lack of needed skills. By extension, talent shortages clearly exist at every level of an organization, both in quantity and quality. Beyond the external factors, significant internal challenges make it extremely difficult for CEOs, the senior team, managers, individual contributors, and human resources to believe in and execute a winning human capital/talent management system. As stated earlier, these challenges are tied to the four D’s of your human capital/talent management processes: Deployment, Diagnosis, Development, and Demarcation. The following challenges, if left unresolved, will exact a significant toll on your organization’s performance. That said, an organization’s ability to successfully combat these issues is in direct proportion to the strength of their human capital/talent management processes.

Deployment Challenges

• Not recruiting, selecting, or promoting based on the competencies required for success

• Aging workforce—concerns about bench strength

• Variable selection ratios—either “too many” or “too few” candidates available per job opportunity

• Talent shortages

• The need to improve selection/promotion accuracy—new-hire ROI

• Turnover issues—inadequate talent and/or fit issues

• Too many interviews—cost, inaccuracy, and legal exposure

• High-potentials are not identified and/or are identified inaccurately

• Succession issues

• Selection/promotion instruments not able to measure Capability, Commitment, and Alignment

• The prevailing inaccurate belief: “The best predictor of future performance is past performance”

• Instruments of questionable validity, reliability, and job relevance

Diagnostic Challenges

• Skill and talent gaps

• Bench strength issues

• Need for better ROI on leaders, teams, and individual contributors

• Disengagement issues

• Turnover issues

• Inadequate or no internal (or external) reference points for calibrating leader, individual contributor, and team Capability, Commitment, and Alignment

• Assessment instruments currently not aligned well with the target competencies required for success

• Assessment instruments that do not provide accurate diagnostic information—relative to strengths and developmental needs, behavioral feedback, and performance development recommendations

• Multiple diagnostic tools not utilized (i.e., multirater, objective assessments, interviews, minisurveys)

Development Challenges

• Discrepant information (i.e., where perceived assessments of actual performance factors disagree with objective assessments of the same performance factors) not uncovered, discussed, and leveraged

• Training and development not linked to competencies

• Training and development not linked to assessments

• Long learning sessions that require too much time away from the job

• Development not multifaceted—coaching, workshops, summits, institutes, e-learning, and on-the job

• Individual Development Planning (IDP) not happening and/or not recent and not based on accurate assessment data

• Learners finding it difficult to determine their development progress against development goals that were established and agreed upon

• Costly training and development, making it difficult to establish a solid ROI

• “Event”-focused training and development, as opposed to continuous

• Organization not innovative enough

• Organization design issues

• Organizational change/transition issues

Demarcation Challenges

• Performance management is a top-down event, not seen as a joint process.

• Performance management is “event” driven, not seen as continuous.

• The word accountability is not a critical theme—not believed in and/or practiced.

• Performance management is a “form” or “software” that needs to be completed.

• Goal setting and performance planning are not aligned with the strategic direction of the organization and/or with accurate assessments that help isolate Capability, Commitment, and Alignment.

• A-team players are not accurately differentiated from the B- and C-team players.

• A-team players receive the same rewards as B- and C-team players

The Stealth Fighter Model

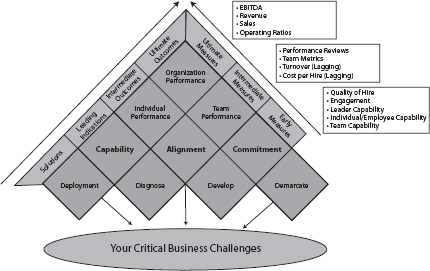

The Stealth Fighter Model offers a compelling, symbolic way to understand the predictive relationships that exist between critical human capital/talent management processes (the four D’s) (Exhibit 1.1), the Leading Indicators (Capability, Commitment, and Alignment—more on these later), intermediate outcomes, and ultimate outcomes. The four D’s essentially act as the four turbocharged engines that propel the Stealth Fighter (the company) toward its target, which is defined as an organization’s Future Desired State and the required competencies to execute both the current and future business strategy. By way of analogy, if the four engines are “well oiled,” functioning at a high level (i.e., optimized), and working together (i.e., integrated), they will propel the Stealth Fighter toward its goal.

Exhibit 1.1: The Stealth Fighter Model

In practical terms, an organization’s Human Capital Value Proposition (HCVP) is the holistic sum of the following practices:

• Deployment—Recruitment, selection, and promotion

• Diagnostic—Assessing competencies and skills

• Development—Training, coaching, action-learning

• Demarcation—Performance management and reward systems

Also included in the HCVP is the relative impact of these practices on multiple levels of business outcome, such as Capability, Commitment, and Alignment (Leading Indicators); intermediate outcomes, such as individual and team performance (lagging indicators); and ultimate outcomes, such as organizational revenue, profits, and operating ratios. Regardless of the exact words used to capture an organization’s HCVP, one thing is sure: The elements identified in the Stealth Fighter Model need to be well thought out, believed in, communicated, executed, and measured (assessed)—continuously.

At its core, a great HCVP encompasses everything employees experience and receive as they are employed by the organization, including the degree of engagement they experience, their comfort and fit within the culture, the quality of leadership, the rewards they experience, and so on. A great HCVP always encompasses the ways in which an organization fulfills the needs, expectations, and dreams of both incumbents and applicants and should be the reason—every day—that leaders, individual contributors, and teams should recommit to give their absolute best. More than anything, a great HCVP clearly connects winning human capital practices to business and operating metrics. As discussed earlier, there is no better way to create the belief in the value of the human capital asset than by demonstrating the connectedness between winning human capital practices and operational success. The research is clear and compelling. The Hackett Group’s 2009 Talent Management Performance Study, involving hundreds of Fortune 500 companies, gathered both qualitative and quantitative data showing enterprise financial, operational, and process payoffs from talent management. Companies with the most mature talent management capabilities (i.e., the four D’s) had significantly greater EBITDA, net profit, return on assets, and return on equity results than those companies that were immature in their talent management processes. Additionally, mature talent management companies had leaders who believed in the value of the human capital asset; who were passionate about investing in building and growing talent; who were relentless in their assessment of leaders, individuals, and teams; and who shared their human capital responsibilities with line managers and the Human Resources function.

It is clear those organizations that excel operationally do so initially with their human capital practices. They select and promote only those leaders and individual contributors who demonstrate (as a result of performance and objective assessments) that they have the highest probability of being successful. These organizations benchmark and essentially certify (as a result of assessments) that leaders, individual contributors, and teams have the Capability, Commitment, and Alignment required to execute strategy; they provide a rich, compelling, engaging, and dynamic learning and performance support environment in which leaders, individual contributors, and teams are motivated to become the best they can be; and they reward and recognize those who truly execute.

A strong HCVP foundation leads to Capability (the can-do), Commitment, (the will-do), and Alignment (the must-do). Great organizations excel in creating the belief that their leaders, individual contributors, and teams have the can-do (i.e., the skills, the talents, the behaviors) to execute, the will-do (i.e., passion, motivation, drive) to execute, and the must-do (i.e., an overwhelming sense of connectedness to the culture, mission, strategy, and values of the organization) to execute. In other words, a strong HCVP is the foundation for an organization to build and sustain a culture in which leaders, individual contributors, and teams become continuously more Capable, Committed, and Aligned. In fact, organizations that excel in selecting and developing talent—with a focus and unwavering commitment to optimizing these Leading Indicators, as indicated earlier, achieve impressive operating results.

Assessment and Structure

According to the Society for Human Resources Talent Management Survey Report, the number one challenge for organizations today is building a deeper reservoir of successors at every level. Our own Trends in Executive Development Research Study (Pearson, 2011), which I coauthored with Bonnie Hagemann from Executive Development Associates, reinforced the Society for Human Resource Management study, again citing bench strength issues as the number one challenge. Predictably, then, most organizations are likely not utilizing predictive assessments and/or a structured process to help with high-potential identification and promotion/succession decisions. In fact, according to PreVisor’s 2009 Assessment Trends Report, only 50 percent of the organizations surveyed indicated that assessments were a critical part of their succession planning processes, and only 33 percent indicated that they used a structured promotion process for all leaders within their organizations. How do organizations overcome this challenge? The answer is clear: There needs to be a passionate and diligent focus on assessment and structure.

The obstacle is that most organizations extract leadership talent from within the ranks of their individual contributor population; if there is a lack of focus on assessments and structure, subjective views of Capability, Commitment, and Alignment are weighted more. This leads to promotion and high-potential decisions often with little or no substantive evaluation of their real capacity to lead others and to execute consistently with the mission of the organization. The advancement rationale seems to be that individuals who are skilled and have excelled on one area will also be likely to excel in other areas, but, of course, this is not a reliable assumption. As indicated throughout this book, a much better basis for making high-potential and promotion decisions lies in the passionate and deliberate assessment and alignment of skills, motivation, and personality required for leadership positions. The notion that the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior is simply not correct. The absolute best predictor of future behavior is past behavior plus overlaying objective assessments plus integrating objective assessment results with perceptions of behavior plus leveraging the integrated results. All that equals predictable and sustainable performance in leaders, individual contributors, and teams:

PB = past behavior

OOA = overlay objective assessments

IAP = integrate assessments with perceptions

LIR = leveraging integrated results

FSSP = future superior and sustainable performance

The Discrepancy Model in Exhibit 1.2 clearly shows the value of overlaying objective assessments on perceptions because corroborative information is always available. That’s good. However, the real value of assessment lies in the inevitable discrepant results where “talent inflation” or “talent deflation” is uncovered. (Without assessment, the discrepancy would never be uncovered.) These two quadrants represent the “secret” to coaching, developing, and helping individuals become the best they can be.

The Four Objectives of Deployment

The four objectives of deployment are to:

Exhibit 1.2: The Discrepancy Model

1. Accurately isolate the organization’s future desired state, including the key position requirements for all positions along with the competencies required to execute the organization’s strategy to achieve the future desired state.

2. Accurately measure (through assessment) a candidate’s deep-rooted skills, abilities, interests, values, and personality factors.

3. Accurately calibrate a candidate’s skills, abilities, interests, personality factors, and values to those positions (and culture) for which there is a high probability of their being successful and staying longer as a result of their being engaged and challenged.

4. Implementing these steps at each level and in each position in the organization so that deployment decisions made involving incumbents (and external candidates) are efficient and effective and drive individual and operational success.

Inherent in this four-part definition of the goals of deployment is the requirement for quality-of-hire/promotion metrics that provide an early indication that the individual selected or promoted, in fact, is a capable, committed, and aligned talent. Waiting for formal performance reviews (lagging indicators) is too late. Typical quality-of-hire/promotion metrics are time to proficiency, surveys of hiring managers, feedback from managers and board, and the like. Leveraging this information early and often and integrating it with previous objective assessment data enable early and effective course correction, which benefits the newly promoted talent and the organization.

What about the role of assessments with incumbent leaders, managers, individual contributors, and teams? Because all incumbents, from the CEO to senior leaders to managers to individual contributors and teams, can be assessed on Capability, Commitment, and Alignment—the Leading Indicators discussed earlier—it would make strategic human capital sense to calibrate and recalibrate on these indicators again in order to enable early course correction and ensure that operating goals are met. It is prudent and, in fact, healthy for an organization to benchmark (i.e., assess the can-do, will-do, and must-do of) senior leaders, managers, individual contributors (salespeople, customer service, etc.), and teams and gain valuable insight into individual and collective strengths and gaps. Using the Discrepancy Model to detect talent inflation and talent deflation, regardless of person, role, or level, offers the incredible opportunity for such individuals to discover the keys to becoming the best they can be.

What’s interesting is when great human capital organizations focus on Leading Indicator assessments. Not only do they employ individual capability assessments—like multirater assessments, communication style assessments, personality assessments, values assessments, simulation assessments, and situational judgment tests, etc., as part of their battery of diagnostics—they also utilize assessments that are effective in accurately diagnosing Commitment and Alignment factors with the use of pulse and engagement surveys. In fact, an organization’s engagement levels are highly predictive of operating results. The Gallup Organization has reported the bleak news on the issue of employee engagement. They reported that 52 percent of the American workforce is disengaged, while another 17 percent is “fundamentally disconnected” from the work they are paid to perform. Said differently, only one in three workers extends the necessary effort that moves organizations forward. Some, like Ritz-Carlton, Marriott Vacation Club, The Home Depot, among others, seem to understand the importance of engagement and tend to measure engagement levels more frequently. Yet most organizations don’t measure enough.

What about the role of the leader? The responsibility that leaders and managers have in fostering a work environment built upon rapport, trust, and credibility cannot be over- or underestimated. An engaged workforce is established by the quality of immediate supervision, as well as by the quality, depth, and effectiveness of communication by the CEO and senior leadership. All employees—from the senior level to individual contributors—must perceive that they are being coached and developed to execute the competencies, skills, and behaviors required for success (i.e., can-do); exercise the passion, drive, and motivation required for success (i.e., will-do); and exhibit the required fit and connectedness to the mission (i.e., must-do). Ultimately, superior operating performance in any organization is the direct result of an unwavering commitment to continuously measure both individual and team Capability, Commitment, and Alignment. As indicated earlier, the focus on calibration and recalibration is the foundation for early course correction and positive individual (i.e., coaching, workshops, summits, institutes, online learning, and on-the-job development) and organization development planning (i.e., organization design changes, change management initiatives, etc.) execution.

What About Demarcation?

Few organizations separate employees into performance categories: A-, B-, and C- team players. If an organization does not engage in a systematic approach to separate talent, both in terms of performance and potential, then it becomes impossible to make the best strategic human resources decisions (i.e., rewards, promotion, succession planning, and termination decisions). After all, employees who consistently execute at the highest levels should be rewarded more than employees who don’t. Great organizations distribute the investments they make in their people accordingly. They differentiate on things like pay, bonuses, opportunities, shifts, and recognition. They reward their best performers with fast-track growth and pay them substantially more than their average performers. They develop and affirm their solid performers who are always trying to raise their game. They also assertively address and remove employees who are underperforming. Their belief—a perceptive and correct one—is that condoning or tolerating poor performance is destructive to high performers’ motivation for greater success and achievement, that leadership’s actions always speak louder than words, and that few things communicate organizational indifference and apathy more loudly than treating high, average, and low performers exactly the same.

Most organizations, unfortunately, struggle with this concept. Typically, they don’t have a way to identify the A, B, and C players, nor do they have a systematic approach and process to ensure that appropriate actions are taken. Most organizations, frankly, conduct one-day succession-planning exercises at corporate headquarters; however, those exercises are done with little objectivity (i.e., objective assessments), resulting in less than effective development planning and succession decisions.