Browse the Web Privately

In the previous chapter, I told you how to keep your connection to the internet private. That can close quite a few holes that might put your privacy at risk—but even if you do all that, as soon as you open a web browser, new risks emerge.

Simply browsing the web reveals a great deal about you personally, your computer, your location, and your habits. There are many steps you can take to reveal less about yourself, although some entail a loss of convenience. Never is this more the case than when shopping on the web. This chapter explores the risks, the measures you can take to avoid them, and certain negative consequences of those measures.

Understand the Privacy Risks of Web Browsing

Assuming you’ve taken all the steps in Keep Your Internet Connection Private, browsing the web privately comes down to two main things:

Preventing information about your browsing activities from being stored on your own device (see On Your Device)

Preventing the sites you visit (including search engines) from collecting information that can identify you personally (see On a Web Server)

(If you have not taken all the necessary steps to secure your internet connection, there’s a third factor to worry about—having information intercepted in transit on its way to or from a website you visit. We’ll come back to that momentarily, in In Transit.)

These categories are often misunderstood, and your actual risk may be greater or less than you imagine.

If information is stored on your computer, it’s available to anyone who has physical or network access to your computer (assuming it’s not protected in some other way, such as by using full-disk encryption or keeping it in a locked cabinet). To use the obvious example, your spouse or roommate might peek at the list of websites you’ve visited when you’re not looking. But some of this stored information, including cookies, is also available to advertisers and other online entities as you browse the web. One person may not care whether someone in his home or office sees what’s on their computer, but may have a principled objection to advertisers knowing about their browsing habits. For another person, the opposite may be the case—advertisers might be irrelevant, but it would be problematic if a family member, coworker, or (let’s just say) the FBI found out what sites they’ve visited.

Even if your computer is squeaky clean, every site you visit may record what pages you’ve read, what search terms you’ve entered, and much more (see On a Web Server, ahead). Unless you’ve logged in to a site with a username and password, it probably won’t know who you are by name, but the other information the site logs could very well be enough to identify you uniquely, given sufficient effort and ingenuity.

Finally, all information moving in either direction between you and a website could be intercepted in transit. If you use an encrypted Wi-Fi connection, you eliminate one avenue that could be used to eavesdrop on your web surfing. If you activate a VPN, you eliminate another. And if you connect to a site that uses HTTPS (which I talk about ahead, in Browse Securely), you reduce the likelihood of in-transit eavesdropping to the point that most of us need not worry about it at all. In the absence of any of these protections, I’d be extremely hesitant to enter or view any sensitive personal information on the web.

That’s a long list of risks. But before freaking out about all the potential privacy risks of web browsing, remember to ask yourself what data you’re trying to keep private, and from whom. Do you care what someone could find if they had physical access to your computer? Do you care what advertisers know about you? Both? Neither?

If you’re downloading stuff or doing things online that could lead to jail time, a lawsuit, a divorce, losing your job, or a combination thereof, you could always, you know, not do that. Regardless of what you do to protect your privacy, someone will probably find out and it will end badly for you. So seriously, stop it.

For what I’ll call “lesser offenses,” you’ll want to be aware of, and take steps to avoid, certain types of data collection.

On Your Device

On your computer or mobile device, you should be aware that browsing the web typically results in at least the following information being stored, for each browser you use:

Browsing history: A list of every webpage you’ve visited, in each browser.

Download history: A list of every file you’ve downloaded—again, in each browser.

Cookies: Information stored on your device by the sites you visit, or by the companies who place ads or other code on those sites. Cookies (see Live Data, ahead) are most often simple settings or random-looking strings of characters that identify your browser session uniquely, but they could also include your username, password, location, and any number of other details. Cookies can then be read when you revisit the same site—or other sites using the same ad network, analytics service, or social networking software.

Zombie cookies: Conventional HTTP cookies aren’t the only way browsers can store persistent data about your behavior. Records similar to cookies can be stored separately when you visit sites with content that uses Flash, Silverlight, HTML5 web storage, and numerous other mechanisms. In some cases, the effect is to resurrect conventional cookies even after you’ve deleted them; hence the nickname zombie cookies.

Web caches: The contents of pages you’ve visited recently, especially images (so the page can load more quickly if you return to it) and favicons (the little icons that appear in your browser’s address bar next to the URL). Some browsers also store thumbnail images of the pages you’ve visited.

The above is only a partial list. Some sites use even sneakier techniques to squirrel away various information about you in a variety of places (see Live Data, ahead, for further detail). In addition to all these things, your device may store a global cache of recent DNS lookups—that is, somewhere outside your browser there may be a list of the domain names you (or your apps) most recently visited along with their IP addresses. If you’re sufficiently curious or motivated to want to remove this cache, you can search the web for “delete DNS cache” to find the procedure for your operating system.

In Transit

The worry about web transactions being observed in transit is that data such as passwords, credit card numbers, photos, messages, and other personally identifiable information could fall into the wrong hands. In fact, the sky’s the limit—anything you type on a webpage or any content displayed on a webpage you view—could get out. Fortunately, this is the least likely privacy threat when it comes to browsing the web and the easiest one to guard against (see Browse Securely, ahead, and also refer back to Keep Your Internet Connection Private).

On a Web Server

Modern web servers can store an astonishing number of facts about every single page request, including (but not limited to) the following:

Time stamp: The date and time of the request.

Time zone: The reported time zone of the requesting device.

IP address: The numeric address of the device you’re using, which may or may not uniquely point to you, but which normally does reveal your approximate geographical location.

Item requested: The URL and size of the page or other resource you loaded. If you visit a page that contains 20 graphics, they’ll register as 20 separate requests.

Referrer: The URL of the page on which you clicked a link to get to this page (if applicable).

Search terms: If you reached this page from a search engine, the terms you searched for may be logged.

User agent: The name and version of your browser. (Many browsers let you change this at will, so what the site records may only be what you tell it your browser is.)

Browser plugins: The names and versions of all your browser plugins or extensions.

Operating system: Your operating system’s name and version.

System fonts: All the fonts installed on your device.

Screen characteristics: The dimensions (in pixels) of your screen, along with color depth.

Furthermore, the server may be able to tell how far down a page you scrolled, how long you spent looking at a page, any items your pointer may have hovered over, which links to external sites you clicked on, and a good deal more.

Although none of these items has your name on it as such (again, assuming you haven’t logged in with unique credentials), you can probably see how a combination of them might point to you uniquely. And if that isn’t already obvious, I invite you to visit a site run by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) called Panopticlick. It examines much of the above data to create a “fingerprint” of the device you’re using, and it tells you how unique that fingerprint is. I tested one of my Macs and found that only one in more than three million browsers has the same fingerprint as mine. That means an advertiser (or anyone else monitoring my web activities) could be reasonably certain that I was the person who requested any given webpage.

Choose a Better Browser

In the remainder of this chapter, I’m going to talk about ways of using your web browser (settings, practices, plugins, extensions and so on) that will improve your privacy. These all assume, however, that you’re using a browser that doesn’t respect your privacy as well as it should in the first place. If you’re committed to using some particular browser, and that browser forces you to go out of your way to maintain some semblance of privacy, well, I guess you do what you gotta do.

But I think it’s worth noting here that there are lots of browsers out there, and some of them are especially good when it comes to privacy. Use a great browser, and a lot of these problems go away by themselves (or, at least, with less effort than you’d otherwise need). Most browsers are free, so you have little to lose and lots to gain by doing most or all of your browsing in a better browser.

I hate to break it to you, but while Chrome may be the world’s most popular browser, it’s not a great choice when it comes to privacy (that is, not unless you go out of your way to modify it, as I discuss in the following pages, and avoid logging in with your Google account). Indeed, the only worse choice I can think of is Internet Explorer, which no human being should ever use anymore, and if you’re still using Internet Explorer, please stop reading right now and download something else—literally anything else—right now. I’ll wait.

Recent versions of Firefox and Safari have made significant strides in improving privacy, even with their default settings (see the sidebar Safari’s Evolving Privacy Features, ahead). So those aren’t bad choices. There’s also TorBrowser (see Browse Anonymously), a customized version of Firefox that offers even more privacy. But, for everyday browsing, I think there are even better choices:

Brave: Brave is a relatively new browser based on the same Chromium engine that powers Chrome—meaning it has a similar look and feel, and can even use Chrome extensions. But it’s faster than Chrome, offers better control of our privacy (including the option to use Tor—again, see Browse Anonymously), and automatically blocks most ads and trackers.

Comodo Dragon and IceDragon: Comodo is a company best known as an issuer of SSL security certificates and other security products. They offer two browsers—for Windows only, sorry—that make me smile just because of their names. Comodo Dragon (get it?) is based on Chromium, while Comodo IceDragon is based on Firefox (and, I guess, designed to appeal to Game of Thrones fans). They both have a full range of privacy and security features built in.

Epic: Epic Privacy Browser is also based on Chromium, but it takes a different approach to privacy than Brave (including blocking most extensions). It has an optional built-in VPN, and blocks most ads and trackers as well as making it more difficult for sites to identify you using browser fingerprinting.

One downside to using browsers like these is that they won’t automatically sync your bookmarks, open tabs, browsing history, and other data across devices. (You can set up syncing in Brave, but it syncs only with copies of Brave running on your other devices, not with Chrome or other browsers.) As with so many things, you’ll have to decide for yourself whether, or to what extent, convenience outweighs privacy.

Even if you are running one of the above browsers, I strongly recommend reading the rest of this chapter and double-checking all relevant settings. Never assume your app will do all the right things automatically.

Go to the Right Site

One of the most surprising privacy threats on the web is impostor sites that look almost exactly like the real thing, but are merely clever copies designed to trick you into supplying your password, credit card number, or other private data. Sometimes these sites appear if you make a slight typing error when entering a URL or if your DNS settings have been compromised, but they’re most commonly reached by clicking a link in a phishing email message. (These messages often warn you that you must “update” or “confirm” your account settings or suffer dire consequences.) Recently, phishing via other avenues, such as Twitter, Facebook, Messages, WhatsApp, SMS, and even sneakily added calendar entries, have also become more common.

Here are some tips to avoid bogus sites:

If you haven’t already done so, follow the advice in Avoid DNS Mischief, in the previous chapter, to avoid most DNS exploits.

Don’t click links in email messages (or in SMS or other sorts of text messages), if you’re not absolutely sure of the sender. If a message that appears to be from your bank, PayPal, Amazon, Apple, or whoever insists that you log in to correct some problem and you’re worried that it might be a legitimate message, open your web browser and manually type the site’s address, making sure you’re using HTTPS. Then log in and see if there are any messages waiting for you. If not, the message is almost certainly fake.

On Mac and Windows systems, hovering over a link in an email message or webpage will usually reveal the link’s URL before you click it. If it looks in any way suspicious (see above), don’t click it: instead, try navigating to the site manually. On mobile devices, many apps will try to show you the destination URL inline, since there is no way to hover. In Safari for iOS, tapping and holding a link reveals the URL and some options.

Avoid clicking links from URL-shortening services like bit.ly, goo.gl, and TinyURL without first checking their destination using a tool like unshorten.it or unshorten.me. Although there are legitimate uses for URL-shortening services (indeed, I frequently use them myself when publicizing Take Control books), they’re often abused to obscure bogus and dangerous links.

Check the site’s certificate. Real banking, commerce, and similar sites nearly always use HTTPS (see Browse Securely, next), and you can usually click a lock icon in your browser’s address bar to verify the site’s SSL certificate. If there’s no certificate, if you see a certificate warning, or if the site doesn’t even use HTTPS, you may be dealing with an impostor.

Let technology help. Most browsers have built-in checks to warn you of sites that might be bogus (see Browser Privacy Settings), as do some third-party plugins (see Web Privacy Software). Be sure to enable these features. In addition, most password managers (see Protect Passwords and Credit Card Info) confirm each site’s identity before entering your credentials.

Browse Securely

Security and privacy are two different things (see the sidebar Privacy vs. Security vs. Anonymity), but sometimes security provides privacy as a side effect. That’s certainly the case with web browsing: if you can ensure that the connection between your browser and the server is securely encrypted, you can also be confident that no one in between can violate your privacy by reading what you send or receive.

The standard way for a website to do this is to use HTTPS, a secure version of the HTTP protocol. A site must install an SSL certificate, which confirms its identity and enables two-way encryption; your browser can independently verify that the certificate is valid and that it’s being used by the correct site. All this happens automatically, behind the scenes.

You’ll know a site uses HTTPS if the URL starts with https: (although many browsers now hide this portion of the URL by default) or if you see a lock icon (often in green, along with the company’s name, right next to the URL in your browser’s address bar). You can then click the lock icon to view details about the certificate and confirm its identity.

The number of sites using HTTPS by default has been growing rapidly, thanks in part to the efforts of a nonprofit organization called Let’s Encrypt that provides free SSL certificates and software for managing them. (Indeed, according to some estimates, more than half the world’s websites now use HTTPS, and public pressure to adopt HTTPS has been growing in recent years as disclosures about state-sponsored surveillance have proliferated.) In fact, I’d go so far as to say you should assume any password or other personal data entered on a site that doesn’t use HTTPS could be intercepted and misused. Some sites use HTTPS only optionally; you might look for a preference you can enable, which will automatically redirect you to the secure site even if you enter a URL starting with http:.

The EFF offers a free browser extension for Chrome, Firefox, and Opera called HTTPSEverywhere (sorry, no Safari or Internet Explorer versions available). This extension maintains a regularly updated list of sites that offer HTTPS connections and instructs your browser to use HTTPS for those sites, even if you visit the site with a non-HTTPS link or URL. It can’t encrypt sites without HTTPS support, but it can prevent you from accidentally visiting an insecure version of a site.

You won’t be at all surprised, I’m sure, to learn that HTTPS, for all its virtues, is not foolproof. I’ve read of numerous hacks and exploits that could enable an attacker to intercept and decrypt a secure web session. (Refer back to the sidebar SSL Implementation Bugs and Issues for an example.) However, these are rare, and browser makers generally fix them in short order. So, your best defense is to make sure you keep your operating system and browsers (including any security updates) current.

Manage Local Storage of Private Data

In On Your Device, I mentioned several types of (potentially) private data that may be stored on your device as you browse or use internet-enabled applications. Here, I want to provide a bit more detail about this data and tell you what you can do about it.

It may be helpful to conceptually divide the stored data into two categories: live data—that is, information that may be sent from your browser to the sites you visit in real time—and historical data, which is accumulated on your device but not transmitted. Both types of data are normally stored separately for each browser you use, on each device.

Live Data

When you visit a site and it sets a cookie, that by itself is generally harmless; it’s just a bit of text stored on your device. When you visit the same site later, it will read that cookie before displaying the page. Cookies are often helpful because they enable sites to save preferences for you, keep track of your login information so you need not enter your credentials each time you visit, and offer continuity (such as remembering which articles you have read) on successive visits.

Cookies have become a privacy problem because they’re often used for tracking you across sites. When you load a webpage, it may include code for ads, social networking widgets, analytics services, or other resources that come from other sites. When those resources load, they can save cookies on your device that record information about you and what you did while viewing the site you’re on. If the next site you visit happens to use an ad, widget, or code from the same network, it can read the cookie to see what you’ve done in the past, and add information about your current visit. This process continues indefinitely, such that you may randomly visit a site for the first time and instantly see ads that are mysteriously targeted to your interests and activities, including items you’ve searched for recently on Amazon, Google, or other sites.

In these cases, it’s not the site you’re visiting that’s setting and reading tracking cookies, but a third-party site or network that has placed code on the page to track you. That’s why you’ll see these types of cookies referred to as third-party cookies. A site may use its own cookies (first-party cookies) for useful purposes such as saving your preferences but permit third parties to use cookies for tracking and other less-noble reasons. Some popular news sites have hundreds of tracking cookies, which pose a privacy risk and cause pages to load much more slowly (and help chew through your data cap). (Browsers don’t normally go out of their way to tell you what cookies a given page has set, but see Web Privacy Software, ahead, to learn one way to keep track of them.)

Browser cookies aren’t the only sort of live data that your device may store and send to sites as you browse. When you use media plugins such as Flash and Silverlight, they may also collect, store, and transmit data in much the same way as conventional cookies—but they do so separately from your browser, which means disabling cookies in your browser may have no effect on this data. Numerous other plugins and extensions can also do this sort of thing, but, without a doubt, Flash cookies are the most common.

Even if you block or delete cookies of all sorts, you may not be in the clear. Some especially aggressive trackers use a variety of techniques (sometimes known as evercookies or zombie cookies) to respawn cookies you’ve deleted or to track you using other methods involving your image cache, JavaScript, and/or HTML5 web storage.

What’s HTML5 web storage, you ask? It’s another way a webpage or application can store data within your browser and access it later. It was designed to be not only faster and more secure than cookies, but also to hold larger quantities of data. And in principle there’s nothing wrong with it—HTML5 web storage can do neat things like cache webmail or map images so that you can read them offline. But it’s still an imperfect system that can be used for undesirable purposes.

Historical Data

Cookies normally stick around on your device for quite some time, so in addition to sending live data about you as you browse the web, they serve as historical evidence of the sites you’ve visited and some of the activities you’ve performed there.

Your browser may also store lists of pages you’ve visited (browsing history), files you’ve downloaded (download history), searches you’ve performed (search history), and information you’ve entered into form fields. Barring a bug or malicious exploit, your browser doesn’t transmit any of this data, but someone could examine your device after the fact and get a detailed record of where you’ve been.

As I said earlier, live data and historical data have entirely different privacy implications. You may find live tracking to be creepy and offensive but have no qualms about someone examining the browsing history on your computer; or you may have no issues with advertisers knowing what you’re up to but prefer to keep that information from, say, your employer (who might take a look at your computer when you’re not at your desk—or even use monitoring software).

Avoid or Remove Local Data

Broadly speaking, you can manage local data storage in either of two ways:

Prevent data from being stored on your device in the first place—using browser settings, a private browsing mode, or third-party plugins/extensions.

Erase stored data after the fact—either manually or using an automated tool.

You can use a number of methods for either approach, as I describe in a moment. But which way is best?

I think most people would agree it’s preferable to avoid getting sick than to cure an illness. By preventing data from being stored locally in the first place, you eliminate both the threat of live tracking and the potential for historical examination. Furthermore, clearing cookies and other local data after the fact may prevent you from being tracked from one session to the next, but not during a single session.

However, depending on your browser, operating system, and device, you may be unable to prevent data from being stored—or at least not with the granularity you prefer. For example, if a browser’s only option is to block all cookies, that may make your web browsing experience worse because it prevents the use of helpful, first-party cookies.

So, what are your options for managing local data?

Private Browsing Modes

Safari, Brave, and Firefox have Private Browsing (in Safari, choose Safari > Private Browsing; in Brave or Firefox, choose File > New Private Window). Google Chrome has Incognito windows (choose File > New Incognito Window; see Figure 10). Internet Explorer has InPrivate (click the gear icon and then choose Safety > InPrivate Browsing), as does Edge (click More ![]() > New InPrivate Window). Most other browsers have something similar.

> New InPrivate Window). Most other browsers have something similar.

While you’re in one of these modes, your browser typically avoids storing data such as cookies; browsing, download, and search histories; form/autofill data; and page or image caches. Because the data isn’t stored at all, it eliminates both tracking and after-the-fact analysis.

I recommend private web browsing modes for people who want to remain private while browsing only occasionally—for specific sites or tasks. Turn them on when you need them; turn them off when you don’t. That way, the bulk of your browsing has the benefits of first-party cookies, histories, and so forth, but private things stay private.

However, please keep the following in mind about private browsing:

The sites you visit with private browsing still collect all the usual information about your device and actions, just as they would any other visitor. (See On a Web Server, above.) To websites, “private browsing” is the same as non-private browsing.

Plugins and extensions—including Flash—could still store data locally if they remain enabled, and there’s no guarantee that an unscrupulous tracker hasn’t invented some other sneaky trick to store data even when browsing privately. Browser beware.

If you download a file, that file may not appear in your download history, but it’ll still be on your device (or perhaps even in your cloud-based storage).

Private browsing doesn’t stop you from manually bookmarking pages.

Although your browser doesn’t store search terms while browsing privately, the search engine might (see Search Privately).

DNS queries, which happen outside your browser, could still be cached on your device.

Someone sniffing your internet connection may still be able to see what sites you connect to, and server logs will still be kept.

Browser Privacy Settings

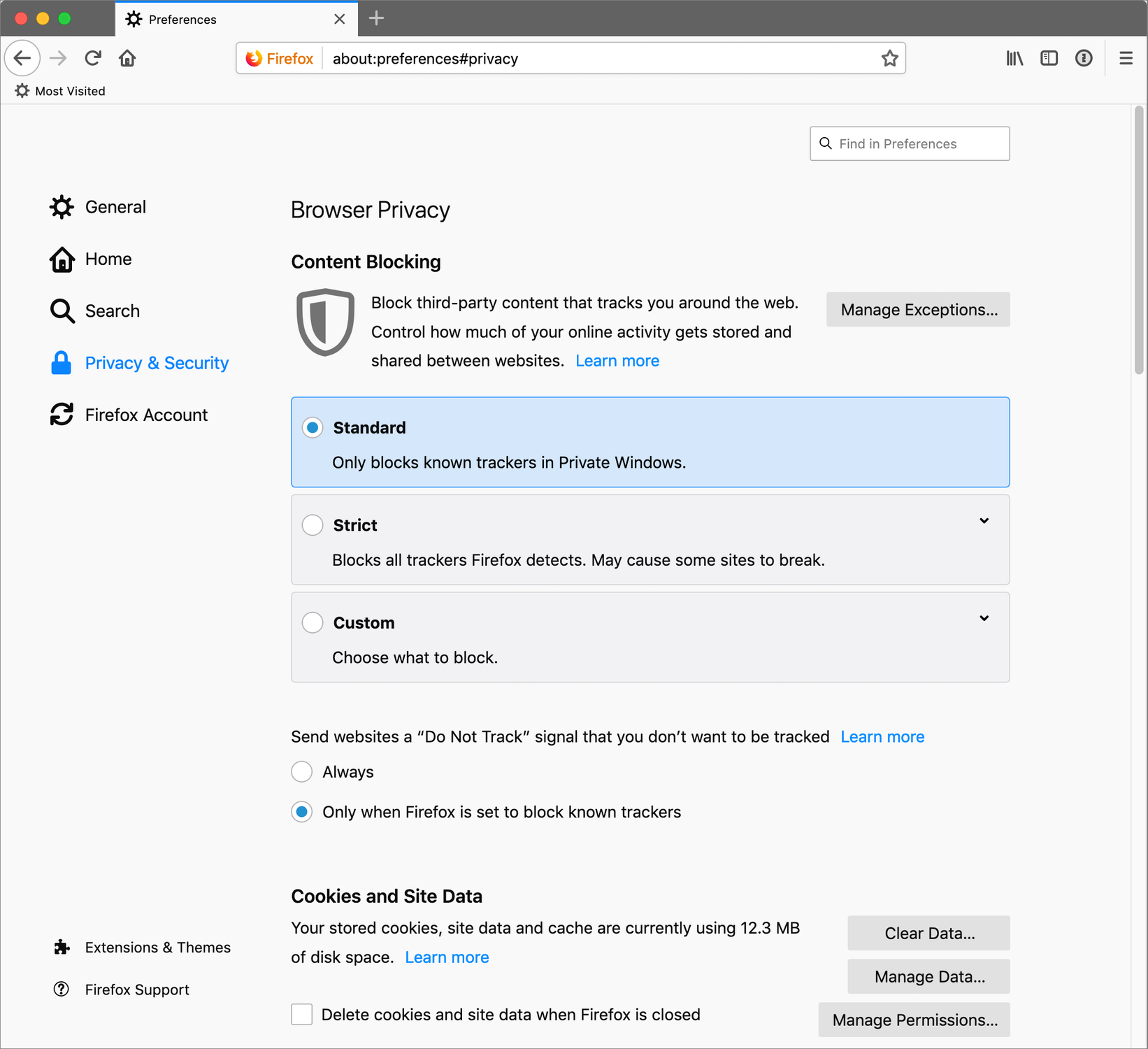

Whereas private browsing modes are temporary, you can usually fine-tune a browser’s preferences to specify permanent settings for which sorts of data should be stored locally (Figure 11). You can usually also examine or delete data already stored.

Once again, the range of choices varies by browser and platform, and I can’t cover every detail here. I will say, however, that you can usually make at least the following choices:

Cookies: Block all cookies; accept all cookies; or (my recommendation) block only third-party cookies. You can also usually view all the stored cookies and delete any of them by site, or all of them en masse. (As I mention ahead in the sidebar Safari’s Evolving Privacy Features, recent versions of Safari have a different spin on this—Intelligent Tracking Prevention, which temporarily stores, then deletes, third-party tracking cookies.)

Do Not Track: Your browser may be able to ask sites not to track you, and I suggest you enable this feature—but most sites ignore the request. (See the sidebar Do Not Track, ahead.)

Phishing and malware protection: Alert you to sites that may be fraudulent (especially phishing sites) and those suspected of containing malware. By all means, turn this on.

Location tracking: Your browser may report your location in order to provide more useful results (for example, local weather, movie times, and stores) without your having to manually specify where you are. I usually find location tracking helpful, and I figure I’m already giving away my general location by my IP address when not using Tor (see Browse Anonymously, ahead) or a VPN, so this isn’t much worse—although, to be fair, location data derived from Wi-Fi triangulation and GPS can be much more precise than what your IP address alone indicates. You can usually enable or disable location tracking on a per-site basis or globally, as you prefer.

Search suggestions and history: When you start typing a search term, your browser may try to fill in the rest for you as a convenience feature. To do so, it may use a locally stored list of your previous searches, but it’s probably also telling the search engine what you’ve typed so far (each and every keystroke!) and asking for a list of matches. This is usually beneficial, but can sometimes reveal more about you than your search terms alone. You can turn these features off.

Here’s how to access privacy settings in popular desktop browsers:

Brave: Enter

brave:settingsinto the address bar. Then click Advanced at the bottom and look under the “Privacy and security” heading. (Note that you must click Content Settings and Clear Browsing Data to access some of the settings.)Edge: Click More

> Settings, click “View advanced settings,” and scroll down to “Privacy and services.”

> Settings, click “View advanced settings,” and scroll down to “Privacy and services.”Firefox: Choose Firefox > Preferences > Privacy & Security.

Google Chrome: Enter

chrome:settingsinto the address bar. Then click Advanced at the bottom and look under the “Privacy and security” heading. (Note that you must click Content Settings and Clear Browsing Data to access some of the settings.)Internet Explorer: Open the Internet Options control panel and look on the Privacy tab. You’ll need to click Sites and Advanced to see certain important settings.

Safari: Choose Safari > Preferences and click Privacy. Also click Websites for some additional privacy-related settings.

Web Privacy Software

Besides using privacy-enhanced browsers like Brave, private browsing modes, and better browser settings, you can also install software that purports to enhance your web privacy. I say “purports” because programs of this sort vary widely in their capabilities. Some are excellent, while others promise more than they can deliver, and some offer little that you couldn’t achieve by clicking a few buttons in your browser.

I couldn’t begin to review the full range of options. So, I’ll just give a few examples.

If you use Safari on macOS (see the sidebar Safari’s Evolving Privacy Features, ahead), it’s safest to use an Apple-sanctioned browser extension from the App Store—use this link for Mojave or later; this one for High Sierra and earlier. Of those, I currently recommend Ghostery Lite, which blocks most ads and trackers while allowing you to easily whitelist sites and customize which types of content are and are not blocked. Other highly rated extensions include Unicorn Blocker and Better Blocker, though the choices change frequently. Some of the other extensions I list ahead also work in Safari to some extent; your mileage may vary.

For other Mac and Windows browsers, one tool I’m quite fond of is uBlock Origin. uBlock is highly customizable, letting you selectively or globally block ads, tracking cookies, social media buttons, and other potentially undesirable elements without interfering with normal browsing and local storage the way private browsing modes do. It also offers protection against domains known to host malware.

I previously recommended Adblock Plus, which has a comparable range of features. It works, but I have a philosophical problem with it: companies like Google and Amazon have paid to be on a list of exclusions so you’ll still see their ads even if you use Adblock Plus. To opt out from seeing these ads, visit Adblock Plus’s Options screen and deselect “Allow some non-intrusive advertising.” Since avoiding ads and associated tracking is the whole point of Adblock Plus, you shouldn’t give it any loopholes!

(The EFF also has a free blocker called Privacy Badger, which is based on the Adblock Plus code but without the creepy pay-to-play exclusions. However, it works only on Chrome, Firefox, and Opera.)

Another fantastic free tool is called Ghostery—available as a cross-platform browser extension for most browsers, not to mention a stand-alone iOS web browser. It displays a list of all trackers of various sorts—both honorable and ignoble—present on any given webpage (Figure 12) and lets you enable or disable them (individually or by category), which can be handy because some sites don’t work without certain trackers. It’s highly educational as well as effective in increasing your privacy.

I should also mention Blur, which features ad and tracker blocking among its many features; see the sidebar Blur: The All-Purpose Privacy Utility for details.

Then there are apps that merely delete locally stored browser data (such as browsing histories, conventional and Flash cookies, and so on) after the fact. It’s easy to do all this manually, without extra software. And in my opinion, such software misleads users by portraying “privacy” as merely preventing someone from seeing what’s on your computer. It does nothing to protect private information in transit, avoid the collection of tracking data as you browse, or disguise your identity in servers’ logs.

My overall recommendation about privacy software is to read the fine print. If a utility claims to solve all your privacy problems, take that claim with a grain of salt. Look into the details to see what it truly does, and whether that’s something you can’t achieve in a simpler way. And remember: prevention is nearly always preferable to cleanup. So this is also a good place to remind you to Avoid Malware, especially the kind that results in endless ads (see the sidebar What About Adware?).

Protect Passwords and Credit Card Info

Your passwords and credit card information are certainly among the items you’ll most want to keep private, but you can’t do very much on the internet without entering a password, and most online shopping requires entering a credit card number. So you can’t realistically avoid ever sending these things over the internet, but you can take steps to keep them private:

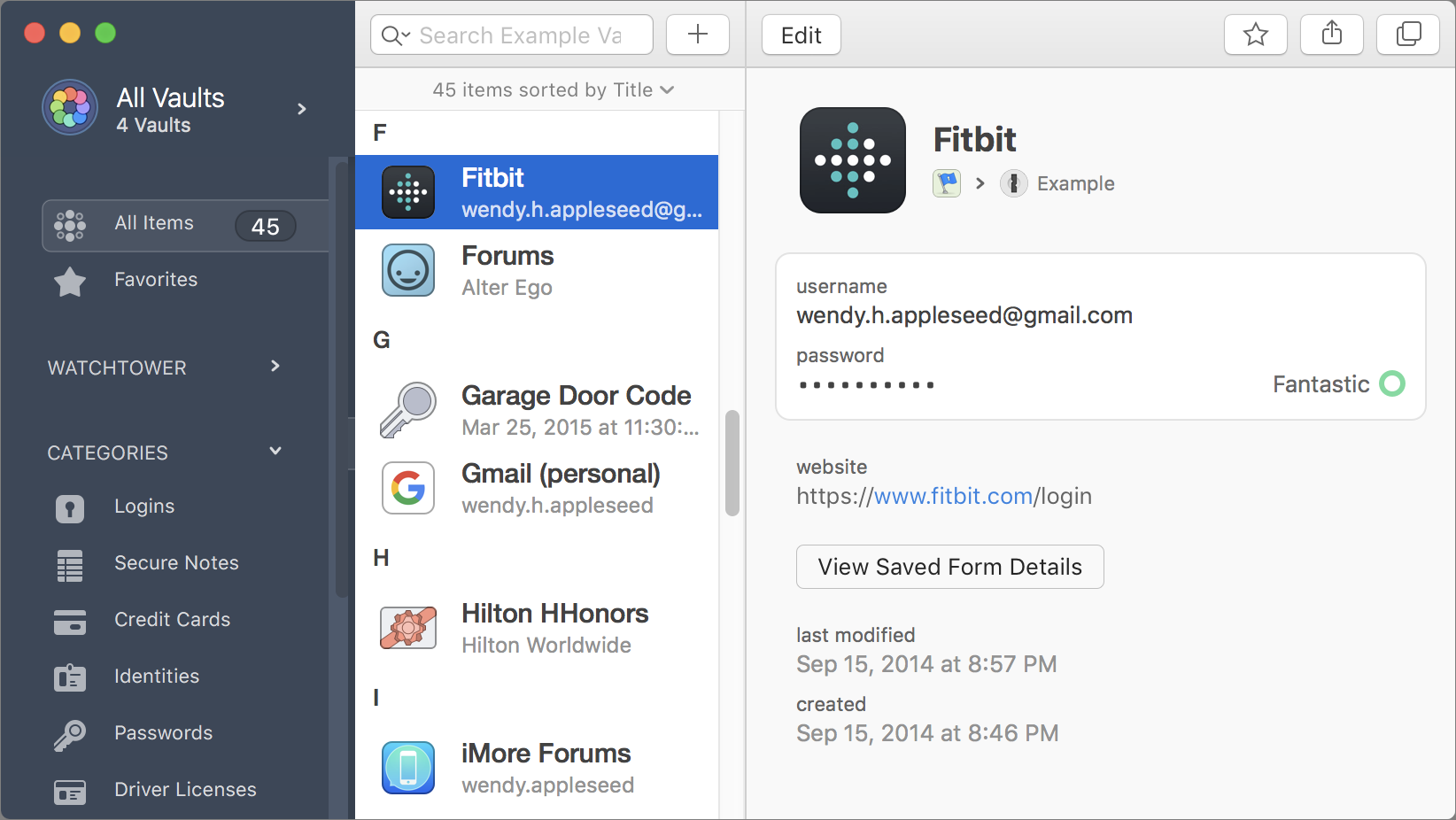

Use a password manager. I’ve previously mentioned password managers—apps such as 1Password (Figure 13), Dashlane, and LastPass—that can generate, securely store, and enter passwords for you. Users of Apple devices can also use a built-in password manager called iCloud Keychain (see the sidebar Security in iMessage and Other Apple Services).

Figure 13: 1Password (Mac version shown here) securely stores passwords, credit card numbers, and other personal data, and syncs them among your devices. You can also use password managers for credit card numbers, secure notes, and other private data. In addition to their obvious benefits, these apps can verify that you’re on the right website before handing over your password—yet another way to avoid phishing and DNS spoofing attacks.

I discuss password managers and other password strategies further in my book Take Control of Your Passwords. (And, if you decide to use 1Password as your password manager, you can read my book about that too: Take Control of 1Password.)

Check for HTTPS. As you saw in Browse Securely, an encrypted web session makes it much safer to send private data, and an unencrypted session is asking for trouble. So look for that lock icon before filling in any web form containing private information.

Later in this chapter, in Shop Online Privately, I discuss further issues involving online commerce.

Search Privately

You know already that you can use a private browsing mode (or change your browser settings) to avoid having your search terms stored on your device. But the search engine could keep a record that someone at such-and-such an IP address performed a certain search at a certain time and date. Furthermore, if you’re logged in to the search site—for example, you’re logged in to your Gmail account while you do a Google search in the same browser—the site will store the search terms in your account, along with all the other data it collects about you. Later, you may use the same search engine on a different device and see those earlier terms pop up again! That could be either helpful or disconcerting.

Google lets you temporarily or permanently Delete searches & other activity from your account, and most other search providers do too. But you might forget, or might not do the right thing in every browser or on every device. And, to be clear: if you log in to your Google account at all in Chrome, Google can still see your searches (and more).

If you want to use a pretty good search engine that won’t log your results, period, try DuckDuckGo, which is now available as a default search option in most modern browsers. All searches are completely anonymous. Nothing is logged, no tracking occurs…and you can disable ads in DuckDuckGo’s settings. And although the results aren’t always as thorough as with Google or Bing, DuckDuckGo is getting better all the time. Another search engine, called StartPage, which makes similar privacy claims and offers the option of using servers located only in Europe, if that’s your preference—but because it’s basically a proxy for Google, there’s still a possibility of Google using browser fingerprinting and other techniques to identify you as an individual when you search. And you won’t find StartPage integrated into as many browsers as DuckDuckGo.

Keep in mind, however, that not all web searches happen in a browser! For example, system-wide searches in macOS and Windows 10 (including those initiated by voice, using Siri or Cortana) have internet components. Apple and Microsoft use Bing by default for web searches, but may also consult numerous other sources, including Wolfram Alpha. And any of these services may log your searches, along with your location and other data. Unfortunately, if you want the benefits of this type of text- or voice-based search, it comes with a certain loss of privacy by definition. However, you can in some cases limit the way searches occur; for example, on a Mac, you can go to System Preferences > Spotlight and uncheck both “Spotlight Suggestions” in the main list and “Allow Spotlight Suggestions in Look up” at the bottom of the window to restrict Spotlight to searching data on your Mac. On Windows, go to Settings > Permissions & History and turn off Windows Cloud Search; also click “Manage the information Cortana can access from this device” and turn off other settings as you prefer.

Browse Anonymously

So far I’ve talked only about private web browsing, but sometimes you may need greater assurances that your web activities are anonymous, meaning they aren’t associated with you individually.

I said in the Introduction that this is a book about ordinary privacy for ordinary people. And frankly, the picture I’m about to paint is far from ordinary. This is something a political dissident or a journalist in an authoritarian country might need to worry about, not a day-to-day privacy concern for regular folk. Still, it’s worth knowing about.

Imagine that your local internet connection is encrypted using a VPN, which also hides your real IP address. Then you use your browser’s private browsing mode to eliminate all local data storage, and connect to a web server using HTTPS, so the entire transaction is encrypted. That’s about as private as you can get—it’s extremely unlikely that any party between your device and the web server will be able to see your information, and similarly unlikely that anyone who examines your device later on will be able to discover evidence of the session either.

However, don’t forget that the server still logs your visit. Server logs may provide enough other information (see On a Web Server to learn about browser fingerprints) to uniquely identify your computer. Furthermore, even though the server doesn’t know your real IP address, your VPN provider does, and it may have kept a log of your session that could be traced back to you (perhaps through warrants or legal action). Finally, even though an encrypted connection protects the contents of the transmitted data, it doesn’t protect low-level routing information, which indicates the data’s origin and destination. (Encryption can’t hide this: intervening routers and switches need that information to pass your data along.) So, by combining all that information, someone could still discover that you were the person who visited a certain page at a certain time. For certain types of web activity, that could put you in deep trouble.

If you need near-complete anonymity when browsing the web (including using webmail), you should know about Tor. Tor, which originally stood for “The Onion Router,” is a system that not only encrypts data but also does so multiple times, sending it through a series of randomly selected relays called nodes (see Figure 14)—each of which knows only about the previous and next node in the chain, but not the information’s origin (unless it happens to be the “entry” node) or destination (unless it’s the “exit” node). This process makes it extremely difficult to determine the source of any web transaction.

To use Tor on a Mac or Windows PC, you download TorBrowser, which is a specially customized version of Firefox that includes strong privacy settings plus the extra software needed to connect to the Tor network (Figure 15). Full instructions for installation and use are on the Tor site. For Android, you’ll want Tor’s Orbot package; for iOS, you can use the third-party Onion Browser.

Tor can dramatically increase the chances that your web activities will be anonymous, but it’s not without its drawbacks. For example:

Several weaknesses in the Tor system have been discovered that could be exploited under the right conditions to reveal private data. For example, someone who runs a Tor exit node could monitor unencrypted traffic flowing between it and the rest of the internet—and indeed, it’s widely believed that the FBI runs a large number of Tor exit nodes to do just that. Using end-to-end encryption such as SSL/TLS reduces the risk of eavesdropping significantly, even if the exit node is compromised.

Someone monitoring your internet connection can tell that you’re using Tor, even though they can’t necessarily tell what you’re doing with it. Some ISPs and countries block all known Tor traffic. There are ways to work around this problem in some instances, but they make the process of web browsing that much more cumbersome.

Merely using Tor could result in unwanted attention from the NSA and other intelligence agencies, including having your encrypted communications retained indefinitely.

Using Tor makes web browsing slow. No, I mean really slow. Furthermore, Flash, QuickTime, and other browser plugins are blocked because they pose too much of a security risk.

Since Tor connections can go through so many different systems, Tor connections almost always have a high latency—the amount of time it takes for data from one end of a connection to reach the other. So you can forget about games and other applications that require fast responses.

Privacy is hard. Anonymity is extremely hard.

Shop Online Privately

I’ve already talked about steps you can take to protect the privacy of your web connection and your credit card information. As long as you’re using an encrypted connection, any purchase you make online should be strictly between you and the vendor. Well, you and the vendor and the vendor’s payment processor and your bank. And perhaps the fulfillment or shipping company. I can’t tell you how to shop anonymously online, but most online purchases from reputable companies are already as private as they can be (which is to say, not very).

One common source of anxiety is giving out your physical address. If you’re purchasing physical goods online, you have to provide a mailing address. Even if you’re buying digital goods with a credit or debit card, you may still be asked for a billing address (which helps to prevent credit card fraud—a good thing!). Other than renting a private mailbox, there’s not much to be done about that. You may not have to provide your home address, but you will have to provide some valid address at which you can receive statements. As long as you can do so over a secure connection, that shouldn’t be anything to worry about.

Another concern is the security of one’s credit or debit card number, even over an encrypted connection. What might happen to it once it’s in the vendor’s hands? Is it safe?

I can’t work up much fear about this, because laws and bank policies protect consumers against fraudulent use of a credit or debit card—or at least limit liability, as long as you report any suspicious transactions promptly. So, keep an eye on your bank statements online and call your bank immediately if anything appears amiss.

If that’s not good enough for you, I can offer a few other suggestions:

Use Apple Pay. If you have a recent-vintage iPhone, iPad, or Mac, you can set it up to use Apple Pay, which works both online (if the site supports it) and at an increasing number of brick-and-mortar stores, vending machines, transit conveyances, and other real-world locations. The great thing about Apple Pay, apart from its convenience, is that merchants never see your credit card number at all, so there’s no chance that data will fall into the wrong hands. (Related, and potentially useful in situations where Apple Pay would not be, is the new Apple Card—see the sidebar What About Apple Card?, ahead.)

Google Pay works similarly, for owners of Android phones, in that it enables you to pay with a credit or debit card without revealing card’s number to the merchant (whether online or offline). However, Google being Google, I can’t help wondering whether my Google Pay purchases would be tracked and added to my profile in order to improve the company’s ad targeting—something I’m keen to avoid.

If an online vendor asks to store your credit card to simplify future purchases, say no. (Sadly, some store it without asking.) If you’re using a password manager to enter credit card details, it’s only a matter of a few clicks anyway. However, even if you follow this policy generally, you might consider making exceptions for sites you shop from frequently, especially those with one-click checkout systems like Amazon and Apple. (It’s rare for a week to go by without my purchasing something—an app, album, ebook, or some other digital media—from one of these vendors, and I have become extremely fond of one-click shopping convenience.)

Use PayPal if that’s an option. Now, I know a lot of people dislike PayPal for one reason or another, but one significant advantage is that it prevents vendors from seeing your credit card number (and, except for goods that must be shipped, your mailing address). Yes, you’re trusting PayPal with a credit card or bank account number, but at least that limits your exposure.

See if your bank offers single-use credit card numbers for online purchases. Mine doesn’t, but many do, and if you want to be sure a credit card number isn’t misused after a single purchase, that could be an option. Alternatively, you can use the free privacy.com service to create virtual credit card numbers on the fly, or use Blur Premium’s card masking service (see the sidebar Blur: The All-Purpose Privacy Utility).

Many other online payment systems exist—some of which go to even greater lengths to protect your privacy. The best known is Bitcoin (which is accepted at an increasing number of online and brick-and-mortar businesses), but numerous other cryptocurrencies have sprung up. Feel free to experiment with these if you’re willing to accept some financial uncertainty. At this point, the entire field is too unpredictable for me to make any specific recommendations.