Improve Email Privacy

When we began discussing this book, former Take Control publisher Adam Engst told me that his rule is, “don’t write anything in email that you couldn’t stomach appearing on the front page of the New York Times.” I said I didn’t think that was a very good rule, and we discussed it (by email, naturally) in what became an increasingly contentious debate. I won’t repeat the entire exchange here, because I’m sure you’ll read it soon enough in the New York Times.

But to summarize, Adam was trying to make the point that you can never have an ironclad guarantee of privacy when it comes to email. In that respect he’s absolutely right, for reasons I’ll explain in a moment. My point was that in many cases, email is the only practical means of communication, and yet it’s completely infeasible for me to avoid ever sending personal facts, business secrets, colorful language, or anything else by email that wouldn’t cause serious problems if made public. I think I’m right about that, too.

But email privacy is extraordinarily difficult to achieve, and the more control you try to exert, the more cumbersome it becomes. By the end of this chapter, you should have a better appreciation of what makes email privacy so tricky. But you’ll also learn how to keep most email safe from casual snooping, how to make top-secret email messages as private as they reasonably can be, and when it’s best to choose an entirely different means of communication.

Understand the Privacy Risks of Email

If you send me an email message, you might have the impression that you and I are the only two people who can read it. Such assumptions are unwise. Let’s look at a few of the places email might be visible to someone other than the sender or recipient:

On your end: Your email client may keep a copy of the messages that you send. If so, anyone who gained access to your device (including thieves and people reading over your shoulder—not to mention your employer) could see what you’ve sent. And, if you have more than one device logged in to the same email account, each device could include a copy of each of your sent messages.

In transit: At minimum, an email message must travel from the device where you compose it to a server, and from a server to the recipient. (If both you and the recipient happen to use the same email server, no further hops are required, but usually messages go to an outgoing email server and then take one or more steps over the internet to the recipient’s email server.) An email message could be intercepted along any segment of this journey—for example, by someone “sniffing” an open Wi-Fi network, or by ISPs, corporations, or government agencies monitoring a router. As I’ll explain shortly, the message data might be encrypted during part of its journey across the internet, but you can’t count on this, even if you use SSL to communicate with your email server.

On email servers: The email server you connect to in order to send a message may hold onto that message only for as long as it takes to send it, and then delete it. Or it may cache the message for much longer—even indefinitely. Unless you run the email server yourself, you have no way to know for sure. (And trust me, you don’t want to run your own email server—I’m speaking from experience.) Once it reaches the recipient’s email server, it’ll stay there at least until the recipient reads it, but more likely it’ll stick around forever, because most modern email systems work best when the server stores the master copies of incoming messages, which then sync to client devices. In any case, for however long the message is on a server somewhere, anyone with access to that server could conceivably read the message without you or the recipient ever knowing.

On the recipient’s end: Everything that’s true on your end is also true on the recipient’s end, with the additional complication that you have no control at all over what the recipient does with a message received from, or sent to, you. And, if the recipient uses multiple devices or services for email, your message may be on any or all of them.

In backups: You, the recipient, and whoever runs email servers that process your messages most likely back up your data to one or more other locations such as local hard disks and cloud storage. (Good for you! Backups are mighty important.) Those backups may be encrypted, but if they aren’t—or if someone with access to the media on which the backups are stored can crack or bypass the encryption—that’s another way your email message could be read.

This isn’t even an exhaustive list, but I hope that it explains Adam’s contention that complete privacy of email messages between you and another party is little more than wishful thinking. Someone who wanted to know what you sent or received by email would have many potential ways to do so.

None of this means someone is reading your email. I’d wager that the overwhelming majority of email messages are never read by anyone other than the sender and recipient. But if you discuss anything sensitive by email, you should be aware that the possibility exists. And, if the contents of a message are such that someone may have financial, legal, or political motivation to read it, the odds of exposure increase. Unfortunately, because email messages are out of your control the instant you hit Send, it’s impossible to quantify the risk.

Email can compromise your privacy in other ways too, even if you never send a single message. I discuss that issue ahead, in Mind Your Incoming Email.

Reduce Email Privacy Risks

Now that I’ve told you how hopeless complete email privacy is, I want to cheer you up a bit by talking about steps you can take to reduce—not eliminate—the potential for email-based privacy threats.

First, I want to tell you about some of the risks of your incoming email in general and what you can do about them. I almost entirely overlooked this important topic in earlier editions of this book, and it deserves a mention.

Then I turn to the messages you send (along with their responses). You don’t want your email messages to fall into the wrong hands, and in this case, you protect your privacy by increasing security. The more of these things you do, the fewer opportunities an attacker will have to read what you send and receive. In most cases, they’ll be enough. And since you now understand that email privacy can’t be perfect, you’ll at least be able to make smarter decisions about what should and shouldn’t go in an email message.

Mind Your Incoming Email

Did you know that merely opening email—even if you don’t reply, or send new messages yourself—can have undesirable privacy implications? It can. I’d like to tell you about a few of them, and suggest some ways to reduce the risks.

Spam

Unsolicited commercial email messages have been a thorn in the side of every email user for decades. Most of the time, they’re just annoying—we delete them and move on, or better yet, use an email provider or third-party spam filtering app or service that zaps most of them automatically. But what do these irritating messages have to do with your privacy?

Well, many of these messages contain links to remote graphics, and it’s easy for senders to customize those links such that merely loading the image informs them that you’ve opened and read their message—something you might not want anyone (especially spammers) to know. Why not? It confirms that your email address is valid and active. But not only that! Loading images reveals information about your device and your IP address (and thus something about your physical location). In some cases, loading remote images can do other nasty things too, such as setting or reading cookies (if you check your email in a browser) or even downloading malware.

The surest way to avoid this problem is to configure your email program not to load remote images automatically. If you receive an email message with images you want to see, you can click a button to override that preference and display them, but you’ll avoid the automatic disclosure of your personal information to people who shouldn’t have it.

Each email app and service has its own way to do this. For example, in Apple Mail for macOS, go to Mail > Preferences > Viewing and uncheck “Load remote content in messages.” You can also read how to do this in Outlook for Windows or Mac, or Gmail; for other email apps, a quick glance at the documentation or a web search should point you in the right direction.

Tracking Beacons

Tracking beacons are a notable subset of trackable remote images in email messages. They can do all the same things I mentioned above, because they’re also links to remote graphics, except they’re invisible—in most cases, they’re tiny, 1-by-1-pixel GIF files. I list them here separately because, even though they can be (and often are) used in spam messages, they’re also used regularly for less sinister purposes.

Tracking beacons let the sender know whether you’ve read their message. This is helpful for marketers, of course, who are trying to gauge the effectiveness and reach of their email campaigns. But it’s also useful for ordinary people like you and me who might be worried that their messages are getting lost or swallowed by spam filters, and want to confirm that they made it safely to their recipients. And it’s as likely as not that someone using such a beacon only discovers (or even cares about) that one piece of information—did they open it or not?—and not other details such as your IP address and location.

So although I consider tracking beacons relatively benign when they appear in non-spam messages (and I’ve even used them myself on occasion), I would not blame you at all for wanting to avoid letting them track you—or at least, exercising control over when they’re permitted to load. Since tracking beacons are just graphics, you can disable them using the same steps I provided above under Spam.

Encryption Bugs

Back in 2017, the news was full of reports about a serious vulnerability in common email encryption systems. The flaw, known as EFAIL, could result in your email client sending an attacker the plaintext contents of encrypted email you’d previously sent or received. It was pretty nasty.

Software developers moved quickly to mitigate the damage this flaw could cause and eventually worked to improve their code to eliminate the problem at the source. Assuming your software is reasonably up to date, EFAIL is no longer a significant threat.

But that’s not to say other comparable flaws might not be discovered in the future. Needless to say, avoiding encryption is not much of a solution! But it turns out that disabling remote images (as we’ve talked about under the previous two headings) was a major factor in reducing one’s vulnerability to this bug—yet another good reason to do that. And always install software updates (especially security updates) as soon as you can, because those are the most definitive way to plug holes like this when they occur.

Phishing and Malware

All of the categories I’ve mentioned so far are privacy risks that require you to do nothing more than open a message, something most of us do without thinking. But there are additional threats that could face you if you take action on the contents of a message. For example:

Phishing: I’ve mentioned phishing in a few other contexts in this book. Basically it’s the effort to trick you into revealing private information—most often, the username and password protecting something of value. In a typical case, an email message convinces you to click a link, which takes you to a site that looks very much like that of your bank, or PayPal, or eBay, or Apple or whatever (see Go to the Right Site). But it’s fake, and once you fill in your credentials, the bad guys have them—they’ll use them to log in to the real site and cause all kinds of havoc.

Malware: I’ve also mentioned malware quite a few times (see, for example, Avoid Malware). It’s nasty stuff with seriously bad privacy implications. And email is one of the ways it spreads—either as an attachment (perhaps one disguised to look like a PDF, Word document, or something else innocuous) or as a link.

How can you avoid these threats? Here are some tips:

Don’t click links in email messages if you’re not sure of their source. I wouldn’t say to avoid clicking links in email messages altogether. Sometimes you have to do that to confirm your email address for a new account, for example, or sometimes a person or company you trust will send you a message about a new product or service you might be interested in, and of course there’ll be a link to that. But…be suspicious. If in doubt, don’t click. (On a Mac or PC, you can usually hover over a link to see its destination before you click it, and if the destination appears to be a shortened URL, a service like unshorten.it can tell you its ultimate destination.) For more on this topic, see the sidebar Email Links: A Case Study, ahead.

Don’t open attachments if you aren’t positive that the sender is trustworthy and the attachment is something you’re expecting. Most of all, don’t open suspicious attachments that are executable files (such as

.exefiles on Windows or.pkgfiles on macOS).Use a password manager. I discussed this in the sidebar Choosing Better Passwords, among other places. If you do accidentally go to a phishing site and you use your password manager to fill in your credentials, it most likely won’t work, because it’ll be able to tell that the site you’re on is not the same one where you set up those credentials in the first place. That’s an extra line of defense against phishing attacks.

Use antispam measures. Whether you use an email provider with its own antispam system, a third-party service, or an app on your Mac or PC, do something to enable automated scanning of your incoming mail to look for spam, phishing attempts, malware, and other undesirable crud.

Log In Securely

In the spectrum of email privacy mistakes, perhaps the worst one is to transmit your username and password to your mail server in unencrypted, human-readable cleartext. If you do that, anyone who intercepts the communication between your device and the server can easily obtain your username and password and then log in to your account and read all your email—and send email under your name. Luckily, this is also among the easiest problems to solve.

Numerous methods are available for authenticating—that is, logging in with a username and password—to incoming and outgoing email servers. The good news is that most of these methods encrypt your password in transit, even if your email and the conduit through which it travels are unencrypted. Odds are excellent that your email app is already set up to authenticate securely, but it never hurts to check.

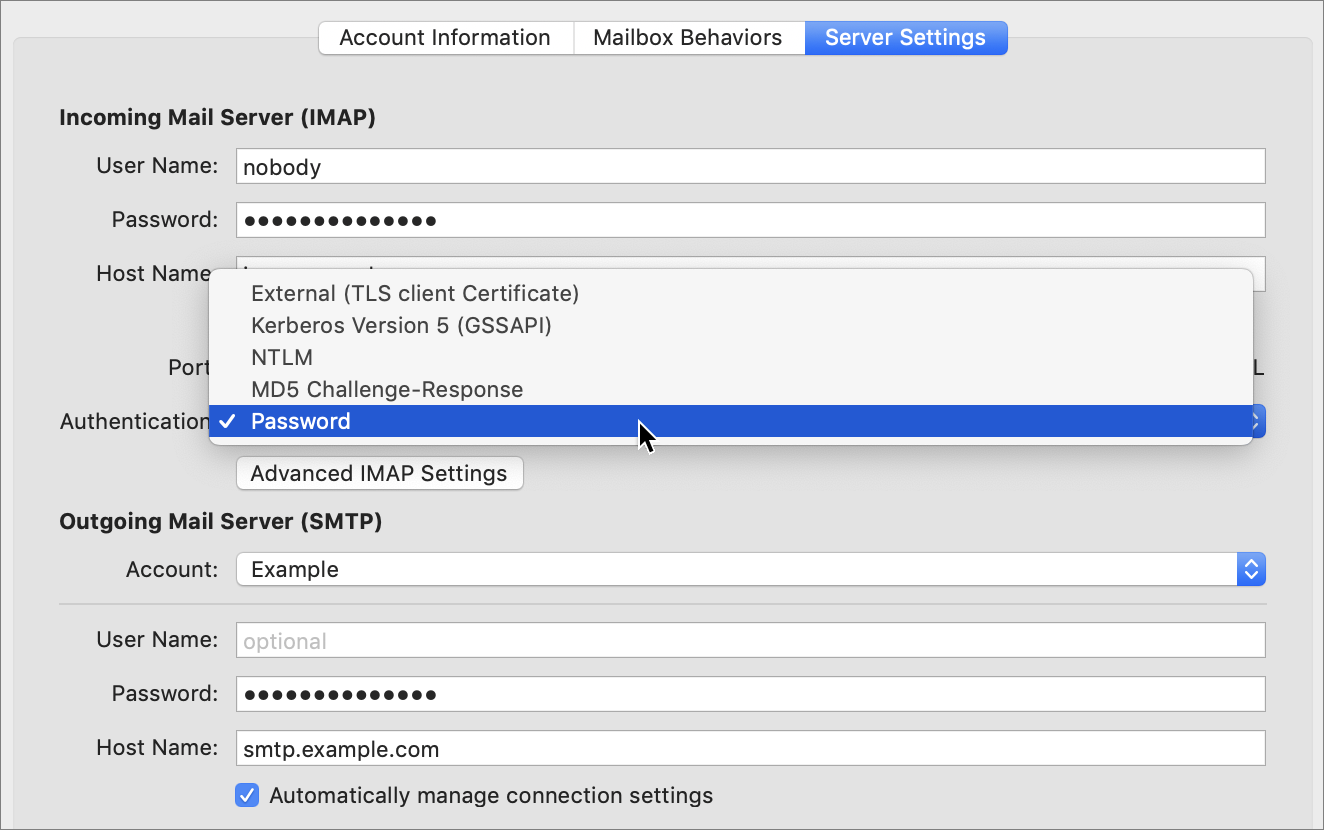

In your email client (such as Apple Mail or Microsoft Outlook), navigate to the preferences or account settings for one of your email accounts (Figure 16). Near your username and password, you’ll usually see an Authentication setting, often in a pop-up menu. (In Mail, you may need to uncheck “Automatically manage connection settings” to see the pop-up menu.) If this says Apple Token, GSSAPI, Kerberos, anything with “MD5” (such as CRAM-MD5, Digest-MD5, or MD5 Challenge-Response), NTLM, or TLS Certificate (the exact wording may vary), you’re in good shape. In addition, if your client is set up to use SSL (see Transfer Email Securely, just ahead), then any authentication method will, by definition, be encrypted. However, if you are not using SSL and the authentication method is set to Login, Password, or Plain, your password is probably being sent in the clear.

Unfortunately, you can’t arbitrarily select a different authentication method; you must choose one that your email server supports. Look at your email provider’s website, or contact its technical support department, to find out what your options are. While you’re at it, check on whether SSL is supported—if it is, that’s your best bet, and then the authentication method is unimportant.

Keep in mind that in most cases, you must go through this process twice for each of your email accounts—once for the incoming (IMAP or POP) server and once for the outgoing (SMTP) server. Microsoft Exchange accounts are an exception to this rule; they use the same server and settings for incoming and outgoing mail.

Transfer Email Securely

After secure authentication, the next logical step to keeping your email private is to use SSL (Secure Sockets Layer), also known as TLS (Transport Layer Security), to secure the connection between your email client and your email server. With SSL enabled, not only are your username and password encrypted on their way to the server, but so are the contents of your incoming and outgoing messages. In this way, SSL prevents eavesdropping on email traveling between your computer or mobile device and your email server, even if you connect to the internet via an unencrypted Wi-Fi connection.

If you check your email in a web browser rather than a stand-alone email client, SSL still applies—you’ll know you’re using it if the URL starts with https: instead of http:, or if your browser displays a lock icon—usually in or near the address bar. If it doesn’t, consult your webmail provider’s documentation to see how you can enable that feature.

Now, I must be clear about the limits of SSL. It protects messages only while they’re in transit between your local device and your email provider (going in either direction). SSL does not mean email messages are stored in an encrypted form on your device, at your email provider, or on the recipient’s device. And, crucially, SSL is not necessarily used for email servers talking to each other. So, even if I use an SSL connection to send a message from my computer to my email server and the recipient of my message does the same thing, my message may travel in unencrypted cleartext from my email server to the recipient’s email server. My message could be intercepted as it moves along that path, and there’s no way for me to know.

In addition, a flaw in SSL’s design or a bug in an SSL implementation could open the door to hackers—it has happened before, as I mentioned in the sidebar SSL Implementation Bugs and Issues.

Even so, SSL is an incredibly good idea, and if I ruled the world, it would be used by default on all email clients and servers. Even though I don’t (yet) rule the world, SSL adoption has been increasing rapidly, and it’s a default setting more often than not. But sometimes you have to turn it on manually, and in a few unfortunate cases, email providers—notably, certain large ISPs—don’t offer it as an option.

Enabling SSL/TLS is usually a matter of selecting a checkbox in your email program, which in all probability will be in the same place as your username, password, and authentication setting (refer back to Figure 16, earlier in this chapter).

As with secure authentication, you must usually enable SSL separately for incoming and outgoing email, for each of your email accounts on each device. If you enable it and your email stops working, your email provider might not support SSL (shame on them), but check with your provider’s tech support to find out one way or the other. If your provider says SSL isn’t available at all, you might consider looking for a new provider that does offer SSL.

And, as a reminder, if you have SSL enabled, your username and password are automatically encrypted along with all other data on that connection, so you can use authentication methods that would send your password in the clear were you not using SSL.

Email Your Doctor, Accountant, or Lawyer Privately

Members of certain professions, such as doctors, accountants, and lawyers, regularly discuss highly personal and sensitive topics with their clients. Given everything I’ve said about the privacy risks of email, you may be wondering whether you can communicate safely with such people by email. The short answer is maybe.

Privacy laws have led to the widespread adoption of secure web portals for communications with doctors and with some financial institutions. The way these work is that both you and the person on the other end connect to a secure website using a username and password, and all email remains solely on that site—it works very much like any other webmail service, except all messages are stored encrypted on the server, and are not accessible via POP or IMAP (or to Gmail, Outlook.com, or other email services).

In some cases, a secure web portal may send you a conventional email message to let you know that a secure message is waiting on the server, and that you should log in to read it. That may seem awkward, but there’s a good reason for it: sending the message directly to you outside the secure system may be not only risky but also illegal.

Confusingly, rules and policies governing secure email vary by country and profession, and they’re always changing. When I lived in France from 2007–2012, I regularly exchanged ordinary email messages with my doctor, but my bank pushed me to use a web portal. Here in the United States, my doctor will only use a web portal, but my banker sometimes sends me conventional email.

If you want to send confidential email to a doctor, accountant, or lawyer, ask if they have access to a secure web portal or a comparably secure method of communication. If not, a phone call might be a better choice. And, if you’re a professional in one of these sensitive occupations and don’t use a web portal to communicate with clients, I strongly recommend reviewing the relevant laws and professional conduct standards for your area to determine your best course of action. Be careful sending confidential information over ordinary email—you could be exposing yourself or others to legal liability.

Encrypt Your Email

Even if you use SSL with all your email accounts, you’ve seen that messages are unencrypted while they sit on various email servers, and often for their journey from one server to another. The only way to be sure they’re private from end to end is for you as the sender to encrypt them, and for the recipient to decrypt them.

Encryption, like SSL, is a great idea, and in an ideal world, perhaps all messages would be encrypted all the time. In a moment I’ll mention a few ways you can go about encrypting messages if you choose to. But first, let me try to talk you out of it. That’s right: I think encrypting email is a less-than-optimal solution for most people, most of the time. Here’s why:

Once the recipient has decrypted your email message, anything could happen to it, and it’s entirely out of your control. A message may stay private all the way to Mr. X, but if he’s not careful (or if his computer or phone is stolen or hacked), your message could still get out.

Configuring an email client to encrypt messages can be (depending on the platform and software) a cumbersome process. Once you’ve done that, encrypting individual messages is usually simple, but requires that your recipients use the same type of encryption, and set up everything correctly on the other end. Even then, in some cases you must go through extra steps to obtain a public key or certificate from the other person before you can send secure email; in other cases, both parties must find some way other than email to swap passwords. You wouldn’t want to go through this bother for every message you send.

Although encryption protects the contents of your messages, it doesn’t protect their headers, which means that someone with access to your encrypted email while in transit or on a server could still see the message subject, sender and recipient’s email addresses, date and time, and other information that may itself be private.

As things currently stand in the United States, the NSA can retain indefinitely any encrypted email messages it happens upon, presumably to help the agency learn how to break that encryption. Unfortunately, the very fact that you encrypt messages—regardless of their content—may mark you as a suspicious person subject to more in-depth monitoring. Encrypting email messages not only draws attention to yourself but could mean that any messages that are intercepted will be kept until the NSA can figure out what they say or decides it’s not worth knowing. Other nations may have even more aggressive policies regarding encrypted email.

Those qualifications aside, if you still want to go for it, there are three main techniques you might use:

S/MIME: Almost all modern email clients, including Apple Mail on macOS and iOS, Outlook, and Thunderbird, support an industry standard called S/MIME (Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions). S/MIME uses a form of public-key cryptography: you give me a public key (in the form of a file called a certificate) that I use to encrypt a message I send you, and then only you can decrypt it with your corresponding private key. To reply to me, you reverse the process, encrypting a message with my public key; I decrypt it with my corresponding private key.

Before you can use S/MIME, you must obtain the necessary certificates and install them on your device; it’s a tedious and non-obvious process. (I describe how to do this in Apple Mail—for both macOS and iOS—in Take Control of Apple Mail.) Your correspondents must also use S/MIME, and you’ll need their public certificates to send them encrypted messages.

PGP/OpenPGP/GnuPG: The commercial PGP (Pretty Good Privacy), owned by Symantec, and the compatible, open-source OpenPGP standard and GnuPG (Gnu Privacy Guard, also known as GPG) software represent another flavor of public-key cryptography. Conceptually, PGP (including OpenPGP and GnuPG) is roughly comparable to S/MIME (in fact, newer versions of GnuPG also support S/MIME), although the implementation is different.

You’ll typically need to install extra software on your device to use PGP, and it may not be available for your favorite platform or version. However, the process of obtaining public/private key pairs is simpler than with S/MIME, and both systems optionally use keyservers, which let you obtain someone else’s public key by looking up a name or email address rather than having to contact that person first. Although most webmail services still don’t offer encryption of any kind, you can use a browser extension for Chrome or Firefox called Mailvelope to add PGP capabilities to nearly any webmail service. In addition, webmail providers Hushmail and StartMail directly support PGP—and there’s an additional web-based option in the next bullet point.

SecureMyEmail, an encrypted email service from WiTopia, lets you use your existing email address and provider. It uses a custom app (on macOS, Windows, iOS, or Android) or a Thunderbird plugin (macOS and Windows); plugins for Apple Mail and Microsoft Outlook are supposedly in the works. By default, messages sent to people who aren’t already SecureMyEmail subscribers will prompt them to sign up. But the service uses PGP behind the scenes, so it’s also compatible with existing PGP keys and tools. The service costs just $0.99 per year per email address.

Proprietary encrypted email: The beauty of S/MIME and PGP/GnuPG is that they’re industry standards that anyone can adopt and that can be used by most email apps. The downside is that they’re complicated to set up and often frustrating to use. An alternative is to use a third-party service that handles all the messy details in the background and presents you with a lovely, straightforward interface, but requires that both parties use the same system. I’ll give you two examples:

ProtonMail is a Swiss service that offers PGP-compatible, web-based encrypted email, as well as iOS and Android apps and (for paid users only), an app called ProtonMail Bridge that enables the service to work with conventional IMAP and SMTP email clients such as Apple Mail, Outlook, and Thunderbird. If you’re sending email to another ProtonMail user, it’s encrypted automatically. When sending email to someone without a ProtonMail account, you can check a box to encrypt it and supply a password; the recipient receives a message with a link to open the message on the ProtonMail website after entering the password. (Of course, this means you must find a way to get the password to the recipient securely; see the sidebar Transferring Passwords Out of Band, ahead.) A basic account is free; paid accounts (starting at €5 per month or €48 per year) add features and storage space. You can send me email via ProtonMail at [email protected].

Tutanota, based in Germany, is another free, web-based encrypted email system that also offers Mac, Windows, Linux, iOS, and Android apps. Much like ProtonMail, you can send encrypted messages to other Tutanota users, while messages to others require a password (which must be communicated separately) for decryption. A premium account, which costs just €12 per year, adds quite a few features (including aliases and custom domains). To contact me via Tutanota, send email to [email protected].

Encrypted attachments: A somewhat simpler, lower-tech approach is to send an ordinary email message containing an attachment that’s encrypted; inside the attachment is the private content you want to transmit. If you don’t already have a suitable app for encrypting files, read Encrypt Transfers, Files, or Both, later, for suggestions. However, there’s just one problem, which is that the recipient needs the password, and you can’t send that by email! The sidebar ahead discusses what to do.

As an alternative for sending the occasional encrypted file, you can use a messaging app that supports end-to-end encryption; see Improve Your Real-Time Communication Privacy.

Send and Receive Email Anonymously

In rare cases, email privacy requires anonymity; revealing your name, your real email address, your IP address, or other personal facts could get you in trouble. I’m thinking, for example, of a confidential source contacting a reporter, an informant telling the police about suspected illegal activities, or someone making politically hazardous statements. In such situations, you may need to disguise the source of the message in such a way that it can’t easily be traced back to you specifically.

Numerous services exist for just such a purpose. A quick web search turns up options that let you send anonymous email with a simple web form (such as SendAnonymousEmail) as well as services that let you set up an account that provides disposable return addresses (such as Anonymous Speech). Blur, mentioned earlier (see Blur: The All-Purpose Privacy Utility), also lets you create disposable email addresses. With some research you’re bound to find many others, including one that suits your particular needs.

However, as usual, I must caution you to read the fine print. Some of these sites log your IP address or other details in such a way that messages could be traced back to you if necessary, and no matter how secure a site claims to be, vulnerabilities could exist that might expose you. And be aware that textual analysis could provide clues to your identity based on word usage and writing habits. Tread carefully if you feel you must use such a service.

Use Email Alternatives

Regardless of encryption or anonymity, you may encounter situations in which email doesn’t make sense as a means of communication. In particular, if you’re worried about something you write being found on someone else’s computer in the future, email is not a good choice.

In the sidebar Transferring Passwords Out of Band, I mentioned several ways you might send someone the password for an encrypted file; all the same methods can be used as alternatives to email if you have something to say that you simply can’t take any chances with. And I go into more detail about one such category in the next chapter, Talk and Chat Privately.

Another option I should mention is the self-destructing digital message. Although these take various forms, the general idea is that you send someone a link to a message on a website, or using a mobile app—and once viewed, that message is visible for only seconds or minutes, after which time it’s permanently deleted. Although such systems aren’t foolproof—the recipient might, for example, take a screenshot of the secret message before it self-destructs, or use file recovery software to undelete it after the fact—they do reduce the risk that a private message will later be discovered on someone else’s device, at least by technically unskilled people.

I found many such services and apps on the web, although I haven’t tried them personally, so I can’t speak to how effective, secure, or easy to use they may be. A few examples: