Introduction: setting the context of business sustainability and globalisation

Abstract:

New business infrastructure and competitive human capital within a dynamic labour market are factors that lead organisations to redefine their business strategies and enhance people management practices. Addressing these efficiently means that organisations will have to strike a balance with their limiting resources and constraints as they work towards business excellence and sustainability. This chapter introduces the context of this book and elaborates the research methodologies which are the basis of this book. It also explains why this book has a focus on Singapore and its linkage to the dynamics of business sustainability under globalisation.

Introduction

The post-2008 global financial crisis and its commensurate impacts prompted businesses around the world to re-examine their capability to be able to better survive and endure through such economic strife and chaos. Also, the term ‘business sustainability’ became a more popular buzzword amongst many managers and corporate boardrooms. Our book presents an Asian perspective on this area of business sustainability and it is about gaining a greater and more nuanced understanding concerning how recent developments and future actions in one part of the world have wider lessons and a global impact. As such, our findings, analysis, conclusions and implications have relevance beyond just Asia.

The book examines the topic of business sustainability from a broad and integrated approach to business. This encapsulates the ‘3Ps’ of: people, prosperity and the planet. Furthermore, the book acknowledges the contributions and challenges for not only multinational companies (MNCs) and large organisations, but also diverse small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in this situation. The numerous benefits that organisations can attain with better governance, social and environmental practices, are also analysed in the following chapters. Importantly, real life cases of recent organisational events and experiences based on managerial views and comments are used. These are the result of research conducted in Singapore.

Why Singapore? Singapore is strategically located at the crossroads of two Asian superpowers – China and India – and is a major international transportation hub, positioned on many sea and air trade routes. Along with Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea, Singapore is one of the Asian Tiger economies. Ranked third in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) report 2009–10 and first among the Asian countries (WEF 2010), Singapore is somewhat representative of more developed Asia. Also, Singapore is a large, busy port and entrepot city-state with an important and leading financial centre and an economy that is based upon foreign MNC capital (Dent 2003: 255). By way of illustration, we can note that foreign transnational corporations (TNCs) accounted for well over half of Singapore’s production, employment and investment and around 80 per cent of its exports by 2000 (Lim 2009: 1). Hence, the business cases, experiences and perspectives that organisations operating in Singapore have on business sustainability carry the flavours of Asia and the world, though there are also a few instances where they may be more unique, specific and context-constrained.

Singapore in context

Singapore is a cosmopolitan world city located 137 kilometers North of the equator in South East Asia between Malaysia (separated by the Straits of Johor to the North) and Indonesia (separated by the Singapore Straits to the South) covering 687 square kilometres over 60 islands and with on-going land reclamation projects. It is very densely populated, with a population of 4.7 million. Its age structure is as follows: 0–14 years old: 14.4 per cent; 15–64 years: 76.7 per cent; 65 + years: 8.9 per cent; with a median age of 39.6 years, population growth of 0.863 per cent and total fertility rate of 1.1 (CIA World Factbook 2010).

Historical and political

From the second century there are early records of settlement on the island. Known by the Javanese name of ‘Temasek’ (‘sea town’), the island was an outpost of the Sumatran Srivijaya empire. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries it was part of the Sultanate of Johor. In 1613 Portuguese raiders burnt the settlement and for the next two centuries the island remained obscure.

Singapore began in 1819, with Sir Stamford Raffles, who spotted the island’s potential as a strategic trading post for South East Asia and signed a treaty to develop the Southern part of Singapore as a British trading post and settlement for the East India Company. Singapore was a territory controlled by a Malay Sultan until 1824, when it became a British possession and then, in 1826, part of the Straits Settlements – a British colony.

During the Second World War the Japanese defeated the British army. Following the war the British allowed Singapore to hold its first general election in 1955. The foundation of modern Singapore started with the formation of the People’s Action Party (PAP) in 1954. Led by Lee Kuan Yew as secretary general, the party sought to attract a following among the mostly poor and non-English speaking masses. The pro-independence victory led to demands for complete self-rule and finally led to internal self-government with a prime minister and cabinet overseeing all matters of government, except for defence and foreign affairs. Elections in 1959 followed and led to a self-governing state.

Singapore declared independence and joined the Malaysian Federation in 1963 and the Republic of Singapore became an independent nation in 1965 (Lepoer 1989). Lee Kuan Yew became the first prime minister and remained so until 1990. Under the administration of Singapore’s second prime minister, Goh Chok Tong, he also served as senior minister and holds the post of minister mentor, a post created when his son, Lee Hsien Loong, became Singapore’s third prime minister in 2004 (The Guardian 2004).

Singapore is a parliamentary republic with a UK-style system of unicameral parliamentary government representing different constituencies. The PAP dominates the political process and has won control of parliament at every election since self-government. The majority of executive powers rest with the cabinet, which is headed by the prime minister. The president has a ceremonial role, although the post was granted some veto powers in 1991.

Economic

In his book, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story 1965–2000 (Lee 2000), Lee Kuan Yew narrates how he and a small group of Singaporean leaders banded together and, by ‘getting the basics right’, transformed a poor and polyglot city into a successful modern nation. Singapore’s growth story has been miraculous, attracting the attention of scholars, politicians and policy-makers from around the world eager to decipher its success formula. A key component in this was the government’s post- independence industrialisation plan – the government assumed a more proactive entrepreneurial role by establishing state enterprises in key sectors such as manufacturing, finance, trading, transportation, shipbuilding and services (Ramirez and Tan 2003). This was done while simultaneously offering incentives to foreign MNCs to set up operations and regional headquarters in Singapore. The government saw this two-pronged strategy as a way to provide the necessary lift for Singapore’s economy to take off (Feng et al. 2004).

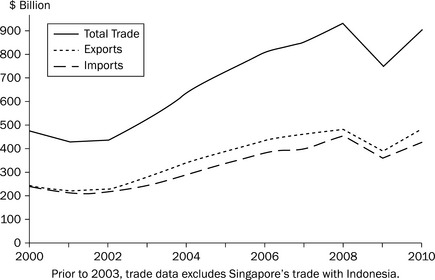

External trade played an important role in Singapore’s emergence as a developed economy. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has contributed to Singapore’s economy over the years. The World Bank also ranks Singapore as the world’s easiest place to do business (World Bank 2010). Furthermore, Singapore is also fast emerging as an optimal destination for the centralisation of services or ‘shared services’ (SEDB 2009). Figure 1.1 refers to the trade performance of Singapore in real terms.

Singapore is now a highly successful and developed economy with high per capita gross domestic product (GDP). Figure 1.2 depicts the real economic growth of the country. The economy depends heavily on exports, particularly in consumer electronics, IT products, pharmaceuticals and a growing financial services sector. The main sectors and industries are: electronics, chemicals, financial services, oil drilling equipment, petroleum refining, rubber processing and product, processed food and beverages, ship repairs, offshore platform construction and entrepot trade. It had exports of US$273.4 billion (2009) within Asia to: Hong Kong (11.57 per cent of the total); Malaysia (11.47 per cent); China (9.76 per cent); Indonesia (9.67 per cent); South Korea (4.65 per cent); and Japan (4.56 per cent).

Singapore’s real GDP growth rate averaged 6.8 per cent between 2004 and 2008, but contracted by 2.1 per cent in 2009 as a result of the post-2008 global financial crisis. Figure 1.3 illustrates the share of GDP by industry.

In 2009, GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) was US$251.3 billion and GDP per capita (PPP) was US$53,900 (CIA World Factbook 2010). It is instructive to look at Singapore in comparison to some other Asian countries in such areas and some pertinent labour market dimensions. These can be seen in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Singapore and Asian economies compared in key labour market dimensions

Source: Estimates from CIA The World Factbook (2010)

From this we can see that Singapore is very small in population and labour force size, and dwarfed by its neighbours in many respects. Singapore also has a relatively low percentage of people under 15 (only Japan’s level is lower) and a high median age (again only higher than Japan’s figure), although its population growth rate is roughly in the middle (better than Japan, South Korea, Thailand and China but worse than Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam) of the Asian countries in our comparison. Such demographic trends have worrying longterm implications for the labour force and strains in the labour market. This is in terms of older workers leaving the labour market and fewer new workers entering the labour market and no option to draw on surplus agricultural workers as a ‘reserve army of labour’ – unlike many of Singapore’s Asian neighbours. Of course other alternatives, such as extending working life and immigration, could ameliorate this strain to some extent. Indeed, our Centre for Seniors case study (in a later chapter) provides an example of some possibilities in this area.

The post-2008 global financial crisis had significant impacts on Singapore as a whole, particulary affecting its labour market. By 2009 there were 3.03 million people in the labour force (76.2 per cent in services and 23.8 per cent in industry), comprising 1.99 million (65.5 per cent) residents and 1.04 million (34.5 per cent) non-residents (MOM 2009: 2). Reflecting the weak job market, the proportion of residents aged 25 to 64 in employment fell for the first time in 6 years, down to 75.8 per cent in June 2009, from a peak of 77 per cent in 2008, as more people became unemployed (MOM 2009: 12).

With people as Singapore’s only natural resource, it is obvious how critical it is to optimise these human resources (HR) and its human capital for its success. To cope with the labour market challenges and to offset the recession, the government subsidised wages, lowered corporate taxes, guaranteed bank loans and spent more on infrastructure as part of a S$20.5 billion (US$13.6 billion) stimulus package (Datamonitor 2009).

Interestingly, the economy has proved to be somewhat resilient and has withstood the challenges of the global economic crisis. Thus, after a contraction of minus 6.8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2009 (Gov Monitor 2010), Singapore claimed the title of fastest-growing economy in the world in 2010, with GDP growth of 17.9 per cent in the first half of that year (Ramesh 2010). Indeed, the annual GDP growth rate of 14.7 per cent in 2010 was a record (even surpassing 1970’s dazzling 13.8 per cent) driven by a surge in the fourth quarter in manufacturing (of 28.2 per cent), while services (accounting for 65 per cent of GDP) also grew (by 8.8 per cent) (BBC News 2011).

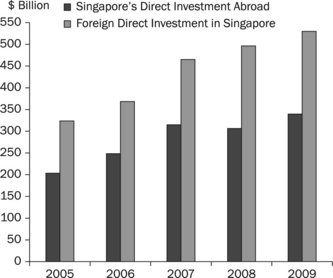

Over the longer-term the government hopes to establish a new growth path that focuses on raising productivity. As part of this, the government has attracted major investments in pharmaceuticals and medical technology products and will continue efforts to establish Singapore as South East Asia’s financial and hi-tech hub. Figure 1.4 notes Singapore’s direct investment abroad as well as foreign direct investment in Singapore.

Thus, education and human capital development are critical to Singapore. English is the main language of instruction in Singapore, which spends 3.2 per cent of GDP on education (CIA World Factbook 2010). We can see the route map of Singapore’s education in the Appendix (Ministry of Education 2010). This also provides details on the stages in education. Primary education is six years, covering English, mother tongue and maths as well as science, social studies, civics and moral education, music, arts and crafts, health education and physical education. Secondary education is four years in special/express, or normal (academic), or normal (technical) courses. Tertiary education is composed of junior colleges/centralised institute (for the academically-inclined pre-university two and three year course), polytechnics (more applied); institute of technical education; arts institutions, Singapore Institute of Technology and four publicly funded universities (National University of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Management University, Singapore University of Technology and Design) and continuing education (SIM University). These indigenous universities are supplemented by a plethora of foreign universities with campuses and delivery arrangements in Singapore.

Cultural

The cultural and social landscape of Singapore is multiethnic and multi-religious, with its people living in relative harmony. Singapore’s ethnic composition is as follows: 76.8 per cent Singaporean; Malay 13.9 per cent; Indian 7.9 per cent; other 1.4 per cent (CIA World Factbook 2010), Caucasians and Eurasians (plus other mixed groups) and Asians of different origins (Singapore Department of Statistics 2010). Some 42 per cent of Singapore’s populace are foreign nationals (UN 2009).

In terms of religions/beliefs, Singapore (2000 census) is: Buddhist 42.5 per cent, Muslim 14.9 per cent, Taoist 8.5 per cent, Hindu 4 per cent, Catholic 4.8 per cent, other Christian 9.8 per cent, other 0.7 per cent, none 14.8 per cent (CIA World Factbook, 2010). Buddhism is the dominant religion, with all three major traditions (Theravada, Mahayana, Vajrayana) present, although most are Chinese of the Mahayana tradition. However, Thailand’s Theravada tradition has seen growing popularity and Tibetan Buddhism is also making a slow inroad into the country in recent years.

In terms of languages, Singapore has speakers of: Mandarin, spoken by 35 per cent; English 23 per cent; Malay 14.1 per cent; Hokkien 11.4 per cent; Cantonese 5.7 per cent; Teochow 4.9 per cent; Tamil 3.2 per cent; Chinese dialects 1.8 per cent; other 0.9 per cent (CIA World Factbook 2010). The government recognises four languages (English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil) with English the dominant language, which became widespread after 1965 when it was implemented as a first language medium in the education system, and in 1987 it was declared the official first language of the education system.

Following our context-setting for Singapore in terms of the historical, political socio-economic background, we next provide details of how our research was undertaken. This is in terms of the types of fieldwork and how it was conducted.

The research and methods

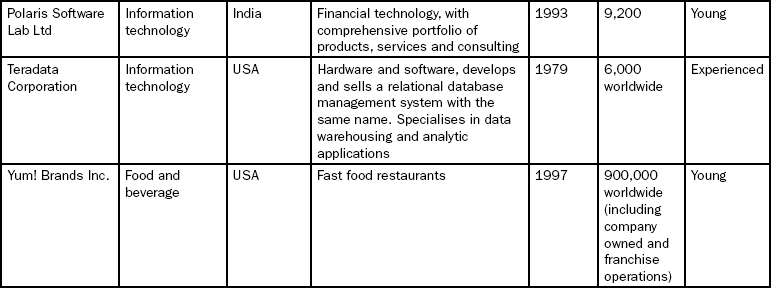

This book is based on research concerning the experiences of managers and their organisations operating in Singapore. This was conducted by the SHRI Research Centre, Singapore in 2009. The work covers the views, key measures, risk management strategies and innovative solutions these organisations had, and wished to have, in order to remain sustainable. The organisations covered a range of sectors, sizes and types (see Table 1.2), with SMEs, voluntary welfare organisations (VWOs) and large local organisations as well as long established MNCs with origins in Asia (India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore), Europe (France, Sweden, Switzerland, UK) and the Americas (US, Mexico).

Table 1.2

Number of organisations by type

| Type of organisations | Number |

| VWOs | 4 |

| Large local | 7 |

| SME | 15 |

| MNCs | 24 |

| Total | 50 |

Source: SHRI (2009)

The fieldwork for our research took six months. We used a case study method. Rather than using samples and following a rigid protocol to examine a limited number of variables, case studies were developed that involved in-depth, longitudinal examination of a single instance or event. Together these cases provide a detailed and nuanced way of looking at events, collecting data, analysing information and reporting results. As a consequence of this, the researcher gains a sharper understanding of what has happened and what might become important for future research (Bent 2006).

Some 489 organisations were ‘purposely’ chosen as they were active SHRI members, organisations and participants and represented the HR profession. From this group some 70 organisations (due to resource constraints) were ‘randomly’ picked. Some 50 organisations expressed their willingness to take part in the project and research, out of which 27 wished to contribute their ideas anonymously and the remaining 23 were happy to be identified, although within this group some individuals did not want to be quoted directly, such as those at Fuji Xerox and iqDynamics. These organisations all operated in Singapore and were invited to participate through e-mail which was later followed up by telephone calls.

Therefore, the methodology applied was ‘random purposeful sampling’ where the cases were chosen at random from the sampling frame of a purposefully selected sample. Overall, the objective of the study was to understand the phenomenon of business sustainability in our time frame of the then current post-2008 global economic crisis situation in Singapore. Though not being technically ‘representative’ of the country, the cases to an extent did portray the situation.

In short, the diverse sectors and size of organisations in our research provided a wide array of means and measures resorted to in order to try to achieve business sustainability in a globalised environment. Further details of the numbers of different types of organisations and their sectoral coverage and spread can be seen in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3

Number of organisations by sector

| Industry sector | Number |

| Chemicals | 2 |

| Document Processing | 2 |

| Electrical and Electronics | 2 |

| Energy | 2 |

| Financial Service | 2 |

| Food and Beverage | 2 |

| Healthcare | 2 |

| Hi-Tech | 3 |

| Hotels and Leisure | 3 |

| Information Technology | 5 |

| Marine (logistics, oil and gas) | 4 |

| Media and Communications | 3 |

| Medical Technology | 3 |

| Recruitment and Consultancy | 2 |

| Security Services | 2 |

| Social and Community | 2 |

| Training and Consultancy | 4 |

| Total | 50 |

Source: SHRI (2009)

Data from the organisations were collected through a suitable mix of methods. We detail these next. First, focus groups were used. The focus group method is a form of group interview in which there are several participants (in addition to the moderator/facilitator). There is an emphasis on a particular, fairly tightly defined topic and the focus is upon interaction within the group and the joint construction of meaning. Some five (due to resource constraints) focus group discussions of three hours each were conducted at the SHRI office. The group size of between nine and eleven people was considered ideal because that is traditionally considered a normal size. The composition of a focus group was based on the homogeneity or similarity of the group members (SMEs, VWOs, large local firms and MNCs). Table 1.4 provides further details of the composition of these groups.

Second, interviews were conducted. Interviews are particularly useful for getting to the story and the details and nuances behind a participant’s experiences. The interviewer can pursue in-depth information around the topic. Interviews may be useful as a follow-up to certain respondents to questionnaires, for example, to further investigate their responses (McNamara 1999). Some 25 interviews of 30 minutes each were conducted at the SHRI office with representatives chosen randomly from the participating organisations, except for two (Discovery and Nuvista), which were conducted over the telephone.

Third, secondary sources were used. This included organisations’ websites, annual reports, newsletters, as well as published news in the media, books, journals, and so on.

For analytical purposes we also developed a typology of ‘types’ of firms. Greiner (1972) proposes a model that explains growth in organisations as a predetermined series of evolutionary and revolutionary phases. Thus, in order to grow, organisations pass through a series of identifiable phases or stages of development and crisis, exhibiting a similar pattern of change. Five phases are proposed, with growth through:

Each growth stage encompassed an evolutionary phase (prolonged periods of growth where no major upheaval occured in organisational practice) and a revolutionary phase (periods of substantial turmoil in organisational life). The evolutionary phases are hypothesised to be about four to eight years in length, while the revolutionary phases are characterised as the crisis phases. At the end of each one of the stages an organisational crisis will occur and the business’s ability to handle these crises will determine its future.

An analogy can be made between such models and processes of growth in an organisation and the number of years of its existence. Initially, these terms were developed to subtly observe how these organisations behaved on the basis of their age; whether the ideologies and experiences of newly formed organisations differed from that of their more experienced counterparts. On the basis of this and their age, our case organisations were put into the following classifications by type as: ‘Newbie’ (less than 5 years old), ‘Young’ (6–20 years old), ‘Experienced’ (21–50 years old), ‘Mature’ (51–100 years old) and ‘Veteran’ (over 100 years old). A summary of our organisations willing to be identified (23) using this classification, and adding in other key aspects, is listed in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5

Summary of case organisations willing to be identified

Source: Statistics Singapore website

We researched different sized organisations, both small and large. SMEs in Singapore, as elsewhere around the globe, are seen to be shock absorbers, innovators and contributors to the country’s economic growth. SMEs play a significant role in terms of employment generation and creating a productive consumer base. To some extent local SMEs help reduce dependency on organisations outside national geographical borders, thereby reducing impacts due to external volatility.

In general, often an SME is classified as such by criteria as the number of employees and the amount of capital or turnover. However, the level of these often varies across countries. Here we give some pertinent examples. In the US the definition of a small business is set by the Small Business Administration (SBA) Size Standards Office government department. The SBA uses the term ‘size standards’ to indicate the largest a concern can be in order to be still considered a small business (and, therefore, able to benefit from targeted funding). The concern cannot be dominant in its field on a national basis and it must also be independently owned and operated. There are size standards for each individual North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) coded industry. This variation is intended to better reflect the important industry differences. The most common size standards are (SBA 2010):

![]() 500 employees for most manufacturing and mining industries

500 employees for most manufacturing and mining industries

![]() 100 employees for wholesale trade industries

100 employees for wholesale trade industries

![]() US$7 million of annual receipts for most retail and service industries

US$7 million of annual receipts for most retail and service industries

![]() US$33.5 million of annual receipts for most general and heavy construction industries

US$33.5 million of annual receipts for most general and heavy construction industries

![]() US$14 million of receipts for all special trade contractors

US$14 million of receipts for all special trade contractors

![]() US$0.75 million of receipts for most agricultural industries.

US$0.75 million of receipts for most agricultural industries.

The UK’s Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) defines SMEs as organisations having fewer than 250 employees with either an annual turnover not exceeding €50 million or a balance sheet totalling €43 million, and not part of a larger enterprise that would fail these tests (BIS 2010). An SME is defined by the European Union as an independent company with fewer than 250 employees and either an annual turnover not exceeding €40 million or a balance sheet not exceeding €27 million (European Commission 2010).

Across Asia several definitions of SMEs are used. India’s Rural Planning and Credit Department of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) defines an SME as a small scale industrial unit, an undertaking in which investment in plant and machinery, does not exceed Rs.1 (approximately US$217,000), except in respect of certain specified items in hosiery, hand tools, drugs and pharmaceuticals, stationery items and sports goods, where this investment limit is Rs.5 crore (often abbreviated cr, this is a unit in the Indian numbering system equal to ten million or 100 lakh and it is widely used in the Indian business context). Units with investment in plant and machinery in excess of the SSI limit and up to Rs.10 crore may be treated as ‘medium enterprises’ (RBI 2010).

In China the definition of SME varies across industries (Li and Rowley 2005). However, usually an organisation with less than 100 employees is considered an SME.

In Japan an organisation with less than 300 employees, or holding assets worth ¥10 million (approximately US$119,660) or less is usually considered an SME. There are further restrictions in wholesaling (less than 50 employees, ¥30 million assets or less) and retailing (less than 50 employees, ¥10 million assets) in defining SMEs (APEC 2010).

The Standards, Productivity and Innovation Board (SPRING) Singapore, a statutory board under the Ministry of Trade and Industry defines SMEs as those with S$15 million (US$9.8 million) or less in fixed asset investment and, for non-manufacturing enterprises, 200 or fewer employees. In 2010 some 99 per cent of all enterprises in Singapore were SMEs employing six out of every ten workers and contributing almost half of the national GDP (SPRING Singapore 2009).

We also researched large firms. Though there is not a clear, universal definition of large local organisations, for the purpose of our study we defined them as those which were incorporated in Singapore and had greater fixed asset investment and number of employees than SMEs.

In addition, we also researched MNCs. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), MNCs include enterprises, whether in public, mixed or private ownership, which own or control production, distribution, services or other facilities outside the country in which they are based (ILO n.d.). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines MNCs as those companies (home) or other entities whose ownership is private, state or mixed, established in different countries (hosts) and so linked that one or more of them may be able to exercise a significant influence over the activities of others and, in particular, to share knowledge and resources with the others. The degrees of autonomy of each entity in relation to the others vary widely from one MNC to another, depending on the nature of the links between such entities and the fields of activity concerned (ILO n.d.). The first modern MNC was the Dutch East India Company, established in 1602.

Singapore has been able to attract MNCs to invest and establish a wide range of business activities. Many of these organisations have even set up their regional headquarters in Singapore. According to a Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore estimate, there are more than 6,000 MNCs in Singapore (MTIS n.d.). The recent report released by the Economic Strategies Committee (ESC) notes the local conducive environment allowing Singapore to become a globally leading ‘living lab’ for businesses to conceptualise, co-create, test bed and commercialise future-ready solutions for global and Asian markets, making Singapore an ideal ‘living lab’ grounded on the ability to pilot with speed, scale and integrity, with a compact urban environment for controlled experimentation, testing and leading adoption (ESC 2010).

Structure of the book

Our book has five further chapters. Chapter 2 briefly outlines the meaning, metrics and measurement of business sustainability, Triple Bottom Lines (TBLs) and introduces the concept of businesses life and linking and reaffirming an organisation’s existence with philosophies. Chapter 3 presents a mix of recent cases of how SMEs, VWOs, large local organisations and MNCs perceive business sustainability. Chapter 4 covers organisational views on business sustainability in terms of: core values, key challenges, reasons for unsustainability, measures taken, risk management strategies, and future challenges. Chapter 5 covers some innovative practices adopted by various organisations, addresses how to raise awareness about business sustainability and introduces an integrated model of it. Finally, Chapter 6 reaffirms our stance and concludes that business sustainability is actually about more than just organisations lasting a long time. Rather, it is a conscious and integrated effort balancing the social, economic and environmental factors.

Conclusion

The impact of the post-2008 global financial crisis and its commensurate economic turmoil for organisations was the background for this research and book. We were particularly interested in business sustainability. Businesses were concerned about how they could continue and survive in the post-crisis environment and what their future concerns should be. As our research and organisational cases and examples show, they did so in different ways.

This book provides an Asian perspective on business sustainability and is about understanding how recent developments and future actions in one part of the world will have a global impact. Our book looks into the topic of business sustainability from a broad and integrated approach to business, encapsulating people, prosperity and planet, our 3Ps. It acknowledges the contributions, challenges and potential of not only big businesses, but also smaller ones. It also analyses the benefits organisations can attain with better governance, social and environmental practices.

This chapter has introduced the context of this book and its basis to readers and set the stage for the next chapter. This introduces the theme of the book and helps readers to discover better the essence of business sustainability.