Action and the feedback cycle

Abstract:

Most higher education institutions now assiduously collect feedback from their students and many produce large and detailed reports (Harvey, 2003). However, it is much less clear how this process results in action and how information on such action is fed back to the students themselves. These two final elements of the feedback cycle are distinct but both vital in making the feedback cycle effective and, most importantly, in engaging the students with the feedback process (Powney and Hall, 1998; Leckey and Neill, 2001). This chapter first explores action processes at a number of institutions that use the Student Satisfaction Approach. Second, the chapter explores the different ways in which institutions feed information on such action back to their students, building on early work by Watson (2003). At these institutions, there is a commitment to taking action as a result of student feedback and the feedback process is closely integrated into the institutional management structure. Action has become a necessary part of the institutional calendar. However, closing the feedback loop is more problematic: institutions use a variety of ways of communicating with their students but there is little agreement on what is most effective.

Introduction

Although much has been written about the collection of students’ feedback on their experiences of higher education (Richardson, 2005), an assumption appears to be made that it is valuable in its own right. One of the most common concerns expressed by students in discussion is that the time they spend in completing questionnaires is wasted because nothing is done as a result. For these students, therefore, institutional claims that student views matter, or that the student voice is listened to, are nullified by the lack of any visible action. It is, therefore, not merely necessary for student feedback to be collected; it is essential that transparent action takes place as a result.

Although a causal link between action and feedback is difficult to prove, it is clear that a rise in satisfaction with an item often coincides with action as a result of regular, annual student feedback surveys. Existing student feedback survey reports indicate that where student data has been used to inform improvement, this has had a direct impact on resulting student satisfaction. Satisfaction, Williams and Kane (2008; 2009) argued, is therefore a dynamic process that depends on institutions asking for feedback from their students and acting upon the information. Furthermore, students need to be made aware of the action that has been taken so that they can see that the feedback process is worthwhile and not merely an empty gesture.

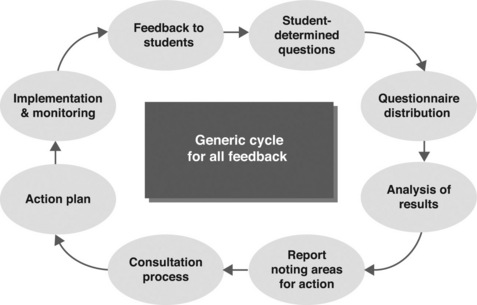

Harvey (2003) argued that student feedback is a cyclical process. First, student input, gained through group feedback processes (Green et al., 1994) and from comments they made on the previous year’s survey, feed into the questionnaire design process. Second, the questionnaire is distributed, returned, scanned and the data analysed. Third, the resulting report feeds into senior management quality improvement processes and action is taken. Finally, action is reported back to the students, who are then again asked for input into the questionnaire design process (see Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 The student feedback/action cycle Source: Harvey L., (2003).

This cycle is a fundamental element of the Student Satisfaction Approach (Harvey et al., 1997). This flexible methodology for collecting and using student feedback was developed at the University of Central England during the 1990s and has been used here and at a large number of higher education institutions in the UK and around the world, and consequently provides a large set of data on student experience and actions taken as a result (Williams and Kane, 2008). This chapter is largely based on data that has been collected as part of the ‘Student Satisfaction’ process because the data is largely comparable.

Action

Feedback and action have long been linked theoretically. Harvey et al. (1997, part 10: 5) argued that the Student Satisfaction approach ‘requires senior institutional managers and divisional managers to ensure that action is taken to address areas of concern’. Leckey and Neill (2001) argued from their experience at the University of Ulster that student evaluation ‘if addressed properly, … is a formal acknowledgement by an institution that it respects student views when taking account of both setting and monitoring standards’ (p. 29). It is a long-standing principle of evaluation that action is taken as a result of canvassing stakeholder experience (Harvey, 1998).

In practice, when an institution takes clear and effective action, satisfaction scores often rise. The two processes are not coincidental: the satisfaction process is a dynamic one and is intended to be so. The results in consequent student satisfaction can sometimes be very clear when presented in longitudinal graphs. For example, satisfaction with an aspect of the university’s computing facilities, and the availability of Internet access, increased across the faculties at the University of Central England (UCE) over the period 1998 to 2007 (Figure 9.2) and the changes correspond to action taken by the university over the same period.

Figure 9.2 Student satisfaction, by faculty, with availability of Internet, UCE, 1996–2007 Source: MacDonald et al., (2005, 2007).

The graph in Figure 9.2 is particularly illuminating because it shows a significant rise in satisfaction with the item on Internet access over the period 1996 to 2000. In 1996, the item was introduced into the questionnaire and it elicited very low satisfaction levels. In 1997, the item again received low satisfaction. As a response, in 1998, the university stated that it was in the process of connecting all faculties to the Internet. One faculty, Law, Humanities and Social Science, was stated to have ‘invested in IT facilities and has a ten-computer room with access to the Internet and email. A further 20 stations with Internet access are currently being set up’ (Aston et al., 1998: 17). It is noticeable in Figure 9.2 that satisfaction levels from Law, Humanities and Social Sciences rose significantly in 1998. The following year, 1999, there was a drop in satisfaction levels, and as a result, further action was taken which focused resources on the faculties that were regarded as unsatisfactory and, as a consequence, significant sums were allocated to extend e-mail operations across the University (Blackwell et al., 1999: 16).1

In 2000, satisfaction was rising, but the focus of university action remained on the Conservatoire and the Technology Innovation Centre (tic, formerly Faculty of Engineering and Computer Technology) as access to the Internet in these faculties was still regarded as unsatisfactory. As a result of poor scores in the 1999 survey, facilities were expanded (Bowes et al., 2000).

Thereafter, satisfaction with the availability of the Internet continued to rise, and as a result, the issue ceased to appear in the action section of the annual report. Significant action by the university was reflected in increased levels of student satisfaction.

However, action cannot always be clear, immediate and dramatically visible in improvement of student satisfaction. Many student concerns are long-term and the responses can only be long-term. A good example of this is the institutional response to assessment and feedback on students’ work. In the UK’s National Student Survey (NSS), shock was expressed by the media and government at the relatively poor performance in two items, the ‘usefulness of lecturers’ feedback on my work’ and the ‘promptness of tutors’/lecturers’ feedback on my work’. These two areas have, for many years, been known by commentators and institutions to be difficult to improve. An exploration of student satisfaction data over 15 years showed that in institutions which have run a detailed Student Satisfaction Survey, predating the limited NSS, satisfaction has increased over time as action has been taken (Williams and Kane, 2008). Satisfaction levels to date, although not high (usually in the region of 50 to 60 per cent), have increased significantly in institutions where tailored satisfaction surveys were instituted. For example, this can be seen clearly in the case of UCE (Figure 9.3).

Assessment and feedback is often mentioned in institutional feedback to staff and students as an area in which action is being taken. At UCE, ‘the issue of promptness of feedback on assignments has always been very important to students and satisfaction varies from faculty to faculty and from course to course’ (Bowes et al., 2000: 11).

Publicly available feedback information at UCE demonstrates that the issue of feedback as it is raised by students has been addressed by management in several different ways since the mid 1990s. Faculties that have scored badly on assessment issues have responded by setting realistic targets for assignment turnaround and, importantly, made assessment and feedback schedules clearer to their students. In 1995–96, for example, UCE instituted more realistic turnaround targets:

In response [to low satisfaction with promptness of feedback] the faculty [of Computing and Information Studies] set a target of a ‘four-working-week turnaround’ on assignments, which has proved very successful. (Geall et al., 1996)

At Sheffield Hallam University, there was a ‘three-week rule’ for the return of feedback to students (Sheffield Hallam University, 2003), although it has been made clear, publicly, that this is difficult to achieve in some faculties. Communication is a consistent feature of action.

Responses to institutional surveys largely fall into two categories. First, the institution clarifies its procedures to the students. Second, the institution recognises that it can improve its own processes.

Real action vs no real action

In the cases highlighted above, action has been taken in response to student concerns. However, it is not always clear what action has been taken in reality. Such ‘actions’ include announcements that issues will be discussed at an indeterminate point in the future. Although this indicates that issues have not been ignored, the survey has little impact if it is not followed up by definite action. Not only does the lack of action limit the impact of the satisfaction survey process, it arguably has a negative impact on the process as students lose faith in it. As Leckey and Neill (2001) argue, ‘feedback is of little use, indeed it is of negative value, if it is not addressed appropriately’ (p. 29).

Monitoring action

Monitoring is necessary to ensure that effective action is taken and followed through. It is necessary to ensure that real action is developed from faculty- or university-level meetings but it is also necessary to make sure that action that has been started is followed through. Too often, in student satisfaction reports, action may be described but there is little information about how it is followed through.

Monitoring is now common, with action particularly on assessment and feedback, arguably because of the near panic engendered by the National Student Survey. However, a common response to issues raised by student satisfaction surveys has long been to institute an effective monitoring system. Different faculties at UCE, for example, used different approaches. In the Faculty of Education, in 2005–06, monitoring of the timing and placing of assessments was carried out in order to make improvements in this area (MacDonald et al., 2006). In the Faculty of Engineering in 1998–99, selected modules were audited and students were specifically asked to comment on this issue. The Board of Studies was charged with determining those modules where promptness of feedback was a problem (Blackwell et al., 1999). In addition, some faculties instituted systems to track student coursework to ensure that feedback is provided according to schedules.

Managing student expectations

A common concern raised amongst practitioners is that student satisfaction surveys may be raising unrealistic expectations among students. However, it is important not to let this deflect researchers and managers from the real purpose of student surveys, which is to gather and hear the student voice. It is important not to pose questions that raise expectations about issues over which an institution has little or no control (for example, car parking) and focus on items that are within the institution’s remit. Nevertheless, it is vital to treat the student voice, as expressed through surveys, with respect and not simply to ‘manage’ student expectations. If a key part of the feedback process is action, then it is vital to respect what the students are saying.

What might be described as ‘unrealistic expectations’ about facilities may in reality be an issue of appropriate training in the use of those facilities. For example, student concerns that there are not enough books relevant to their course in the library may not be a false expectation but it might also be that they have not been given enough training in the use of library resources. This might, therefore, involve further discussions with staff and students about what is necessary for students to get more out of their experience of the library. At UCE, following poor library scores for the ease of locating books on the shelves and for other items in 2002 (see Figure 9.4), a series of focus groups were held with staff and students from the Faculty of Law and Social Sciences. This was aimed at identifying the main areas of concern. The discussions led to a report and the designation of adequate funding to addressing stock concerns. Over the summer period, the library carried out an extensive programme of renewal and replacement of its stock and in following years the satisfaction level rose dramatically (MacDonald et al., 2003).

Figure 9.4 Student perceptions of ease of locating books on shelves, UCE, 1996–2007 Source: MacDonald et al., (2005, 2007).

In addition, the library’s large-scale refurbishment programme, carried out over the period from 2005 to 2007, significantly improved the appearance, user-friendliness and content of the library, all of which may have contributed to general satisfaction with library items in the annual student satisfaction survey.

Another example related to realistic or unrealistic expectations is the issue of the promptness of tutors’ feedback on students’ work. The institutional response should not be aimed at ‘managing student expectations’; rather it should be about making clear what is possible and what is relevant to the students. For instance, it may be true that lecturers cannot provide feedback within two weeks when they have several hundred papers to mark, let alone other duties to perform. This is entirely understandable; however, it does not help the students if they need the feedback for an assignment that follows shortly afterwards. An argument is then necessary for a change in the timetabling of assignments rather than an increased burden on the lecturers. Indeed, as Williams and Kane found (2008: 67), ‘ensuring an even spread of assessments is one approach that has been used by institutions’. At the UCE, over the period 2005–07, attempts were made to spread assignments more evenly by changing the teaching programme (MacDonald et al., 2007).

Some institutions are finding that the assessment load on their students is too great and have taken measures to reduce it. The response from at least one UK university has been to change courses from a 15- to a 20-credit framework (Williams and Kane, 2008). This is reflected in the wider discussion about assessment – modular structures have led to shorter courses and, as a result, more frequent assessment (Gibbs, 2006).

Students’ ownership of the feedback process

There remains, however, little direct evidence that students are more likely to complete questionnaires as a result of knowing that action is taken as a result of their participation. Experience suggests that surveys tend to attract larger numbers of respondents when the purpose is clear and action results.

A brief scan of comments from students at three universities relating directly to their institutional satisfaction questionnaires showed, that in the majority of cases where there were comments, the concern is with the size or relevance of the questionnaire.2 However, there were several comments that showed a deeper engagement with the overall purpose of the survey process.

Some comments were positive and recognised that the questionnaire process is a valuable method of improving the institution. The following comments reflect this view:

Questionnaire is a good idea so the University can try and improve even more. (Student 1, University B, 2007).

This questionnaire is an excellent idea since it is impossible for the management to just guess what the students are pleased with or having difficulties as well. (Student 2, University A, 2006).

Questionnaire is spot on highlighting relevant importance of how the points of the course should be structured and followed through consistently. This can improve both performances between staff and students. (Student 3, University A, 2007).

Some comments demonstrated a degree of cynicism about the process. These students argued that the process is not about real action but about fulfilling requirements. The following comments reflect this view:

If it would make a difference I would fill it in. This is an exercise to be seen to be doing the right thing. (Student 1, University A, 2007).

Does any of this feedback actually get acted upon? (Student 2, University C, 2009).

Some students believe that the survey is a pointless exercise because they can see no action resulting from completing the questionnaire annually:

This would be the third questionnaire I have completed. There has been no response to the complaints raised by way of the questionnaire or as a result of writing to the Vice Chancellor direct. And pretty pointless. (Student 1, University A, 2007).

I usually relish the opportunity to give feedback as it is a very important tool. However, it needs to be relevant to the participant and not take up so much time. (Student 2, University A, 2007).

Tell us what exactly you have done having received these feedbacks instead of repeatedly sending so many questionnaire forms with a cheap 25 pound lure. (Student 3, University C, 2009).

Interestingly, one student felt that the survey process would be better operated by the students themselves in order to make it more relevant:

This questionnaire is better handled by students with more/adequate knowledge of the university as a whole, i.e. students who have been on the campus for up to or over one year. (Student 1, University A, 2006).

Such a view has merit and student ownership occurs, for example, at Lund University in Sweden and in some UK universities, such as the University of Bath, where the student satisfaction survey was established ‘as a partnership between the University of Bath and the Students’ Union as part of the University of Bath’s Learning and Teaching Strategy’ (University of Bath, 2009). It is interesting to note that the University of Bath achieves a relatively high response rate compared with other UK institutions, indicating a potentially important role for the Students’ Union in the feedback process.

Feedback to students

Actions taken as a result of a student satisfaction survey need to be fed back to the students to make it clear that their voice is listened to. Harvey et al. (1997) claimed that such ‘feedback is not only a courtesy to those who have taken the time to respond but it is also essential to demonstrate that the process both identifies areas of student concern and does something about them’. Leckey and Neil (2001) argued that what is important is what is done with this student input, namely: ‘what action is taken; how the outcomes are conveyed to the students themselves’ (p. 31).

In their study Closing the Loop, Powney and Hall (1998) found that students were less likely to take ownership of the student feedback process or even the wider quality improvement process if they were unaware of action that resulted. Richardson (2005) argued that students are more likely to be sceptical about the value of taking ownership of feedback processes where little institutional response is visible:

Many students and teachers believe that student feedback is useful and informative, but many teachers and institutions do not take student feedback sufficiently seriously. The main issues are: the interpretation of feedback; institutional reward structures; the publication of feedback; and a sense of ownership of feedback on the part of both teachers and students. (p. 410)

This is a difficult issue and many institutions have tried different approaches over the last twenty years with varying degrees of success.

At its simplest, feedback can be provided through a detailed leaflet. For example, at the UCE, a four-page feedback flyer, Update, was developed, which outlined the main actions that were taken by the university and faculties as a result of the survey. This was based on the principles laid out by Harvey et al. (1997). The leaflet was distributed with the following year’s questionnaire in order both to inform the students of actions taken as a result of the survey and to encourage students to complete the new survey. Other institutions have followed this model: Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand, University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Australia, and Lincoln University and the University of Greenwich in England have all produced substantial newsletters detailing action as a result of their student satisfaction surveys (Watson, 2003).

A shorter, glossier approach is sometimes thought to be more effective in catching the student’s eye. At Sheffield Hallam University, a ‘glossy, marketing-type leaflet’ (Watson, 2003: 151) was produced in 2002–03, outlining the main action outcomes of the student satisfaction survey. A similar approach was taken at ‘Midland University’. Key actions across the university are summarised in a glossy, colourful one-page leaflet. As in the UCE model, this is distributed with the following year’s questionnaire in order to encourage students to complete the survey and demonstrate that action has resulted since the previous year.

These examples are paper-based, but other institutions use a range of different media to present the message that action has been taken. Bulletin boards, student websites and student radio have all been used to broadcast the message that student feedback is acted upon. This approach has been used by the University of Portsmouth and by Sheffield Hallam University as a way of supporting the paper leaflet. UTS was considering placing an item in the ‘What’s New’ section of their home page and sending batched emails outlining results to their students (Watson, 2003). Sheffield Hallam University sent a short e-mail to all students with just the headline issue that had been implemented as a result of the last Student Satisfaction Survey, with a link to a more detailed account of changes. This was just prior to the invitation to complete the current year’s survey.

As Watson found (2003), a further channel for feeding back information on action is through direct communication with students. Two universities in the UK in Watson’s study used student representative fora to disseminate information. Another university forwarded the student experience report and resulting action memoranda to the students’ association. However, this approach relies upon student representatives forwarding this information to their peers. At Lund University in Sweden, the students are closely involved in the process and results of that University’s Student Barometer (Lärobarometern) are discussed with the students at a special conference (Nilsson, 2001).

Students’ perspectives on the feedback flyer

However, it is unclear how effective different feedback methods are and this is another area in which further research would be useful. At University A in March 2007, a small project was carried out to collect views on the efficacy of the feedback flyer. The following comments suggested that the flyer was considered rather dull and unappealing:

Seen but not read because it’s boring. (Student 1)

Boring, only interested in the iPod [the participant prize], didn’t like the letter from directorate, no colour, grey, need more pictures, don’t recognise it as a letter, doesn’t appeal to the eye, more summaries, looks like a dull newspaper article, looks like a political leaflet. (Student 2)

The following comments suggest that the paper-format of a flyer is dull, and that it would be better presented on the Internet in a more personal manner:

Colourful, creative, more diagrams, more eye-catching, prefer to receive it by email, on a website, combine it with a newsletter, personalised letter. (Student 1)

Seeing the results happen, put feedback notices where applicable, email findings to the university email accounts, eye-catching video or link to faculty websites, put it on moodle [University virtual learning environment]. (Student 2)

Conclusions

The material covered in this chapter indicates, above all, that if an institution takes real action on the basis of what its students tell it through large-scale institutional feedback surveys and makes it clear that action has been taken, satisfaction increases over time. Institutional feedback surveys, therefore, fulfil the long-standing and core principle of survey development that action is taken as a result of canvassing stakeholder opinion.

It is vital that real action is taken and seen to be taken, otherwise students are disillusioned with the survey process. It is important that institutions ensure, through effective monitoring processes, that real action is taken. Institutions must not view the survey process simply as an exercise in ‘managing expectations’: students are not ‘customers’ but principal stakeholders whose voice provides direct and valuable data on their experience. Many issues raised by students are not solved by attempts to reduce their expectations but by working with students and within what is realistic for all stakeholders, including academic staff.

As part of the courtesy to students for taking time to complete questionnaires, it is necessary to make it clear to them that action has been taken. The survey process thus has a clear purpose of which respondents are aware. In order to make this process more effective, further research is necessary into the nature of student responses to institutional student feedback surveys and how students respond to feedback information about action.

A commitment to a methodology such as the Student Satisfaction Approach, it is argued (Harvey, 1997), is principally the result of an institution recognising that certain aspects of the student experience require improvement and that listening and acting upon the students’ own experience through regular feedback surveys is one way of doing so. This is a mature approach to informing change but, arguably, recent responses to the NSS in the UK are more concerned with appearing well in another set of league tables than committing to a robust and transparent quality (feedback) cycle.

References

Aston, J., Blackwell, A., Williamson, E., Williams, A., Harvey, L., Plimmer, L., Bowes, L., Moon, S., Owen, B. The 1998 Report on the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 1998.

Blackwell, A., Harvey, L., Bowes, L., Williamson, E., Lane, C., Howard, C., Marlow-Hayes, N., Plimmer, L., Williams, A. The 1999 Report on the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 1999.

Bowes, L., Harvey, L., Marlow-Hayes, N., Moon, S., Plimmer, L. The 2000 Report on the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 2000.

Geall, V., Moon, S., Harvey, L., Plimmer, L., Bowes, L., Montague, G. The 1996 Report on the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 1996.

Gibbs, P. Why assessment is changing. In: Bryan C., Clegg K., eds. Innovative Assessment in Higher Education. London: Routledge; 2006:11–22.

Green, D., Brannigan, C., Mazelan, P., Giles, L. Measuring student satisfaction: a method of improving the quality of the student’s experience. In: Haselgrove S., ed. The Student Experience. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, 1994.

Harvey, J., Evaluation Cookbook. Edinburgh: Heriot-Watt University, 1998 Available online at (accessed 21 September 2009). http://www.icbl.hw.ac.uk/ltdi/cookbook/cookbook.pdf

Harvey, L. Editorial: student feedback. Quality in Higher Education. 2003; 9(1):3–20.

Harvey, L., Moon, S., Plimmer, L. The Student Satisfaction Manual. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press; 1997.

Leckey, J., Neill, N. Quantifying quality: the importance of student feedback. Quality in Higher Education. 2001; 7(1):19–32.

MacDonald, M., Saldaña, A., Williams, J. The 1996 Report on the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 2003.

MacDonald, M., Schwarz, J., Cappuccini, G., Kane, D., Gorman, P., Price, J., Sagu, S., Williams, J. The 2005 Report of the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 2005.

MacDonald, M., Williams, J., Gorman, P., Cappuccini-Ansfield, G., Kane, D., Schwarz, J., Sagu, S. The 2006 Report of the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 2006.

MacDonald, M., Williams, J., Kane, D., Gorman, P., Smith, E., Sagu, S., Cappuccini-Ansfield, G. The 2007 Report on the Student Experience at UCE Birmingham. Birmingham: University of Central England; 2007.

MacDonald, M., Williams, J., Schwarz, J., Gorman, P., Mena, P., Rawlins, L. The 2004 Report of the Student Experience at UCE. Birmingham: University of Central England; 2004.

Nilsson, K.-A., The action process of the student barometer: a profile of Lund University, Sweden. Update: the Newsletter of the Centre for Research into Quality, 2001. [15 (March)].

Powney, J., Hall, S. Closing the Loop: The impact of student feedback on student feedback on students’ subsequent learning. Edinburgh: Scottish Council for Research in Education; 1998.

Richardson, J.T.E. Instruments for obtaining student feedback: a review of the literature. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. 2005; 30(4):387–415.

Sheffield Hallam University (SHU). Student Experience Survey 2002 – feedback. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University; 2003. [Cited in Williams and Kane (2008)].

University of Bath, Learning and Teaching Enhancement Office: Student Satisfaction Survey 2003. University of Bath Website. 2009 Available online at (accessed 23 September 2009). http://www.bath.ac.uk/learningandteaching/surveys/ses/2003

Watson, S. Closing the Feedback Loop: Ensuring effective action from student feedback. Tertiary Education and Management. 2003; 9(2):145–157.

Williams, J., Kane, D. Exploring the National Student Survey: assessment and feedback issues. York: Higher Education Academy; 2008.

Williams, J., Kane, D. Assessment and Feedback: Institutional Experiences of Student Feedback, 1996 to 2007. Higher Education Quarterly. 2009; 63(3):264–286.

1Although there is no clear evidence from the data or existing (published) reports to explain this phenomenon, experience suggests that it is quite common for satisfaction levels to drop noticeably following an initial rise. Arguably, this may be explained by increased demand following initial outlay or by a failure of an institution to keep up concerted action.

2The three UK institutions have been anonymised because the student comments from the questionnaires largely remain unpublished. University A is a large metropolitan institution which was formerly a polytechnic. University B is a medium-sized former polytechnic. University C is a small out-of-town campus university founded in the 1960s.