For years, the United States has been urged to align its weights and measures with the rest of the world, but in 2007, it was one of only three nations that had not yet officially converted to the metric system. This seems odd, given that the United States has little in common with the other two holdouts—Liberia and Myanmar. It also seems strange because, as far back as 1958, the Federal Register contained provisions that "all calibrations in the U.S. customary system of weights and measurements carried out by the National Bureau of Standards will continue to be based on metric measurement and standards." And seems even more peculiar because in 1996 all federal agencies were ordered to adopt the metric system. Adhering to a thousand-year-old English system that even the English have been abandoning imposes many disadvantages. It handicaps international commerce, for example, and it led to measurement confusion in the design of the Hubble space telescope that cost taxpayers millions of dollars. Yet little progress has been made in converting to a different system.

America's metric inertia illustrates pervasive and predictable realities of change that repeatedly scuttle promising innovations. Organizations spend millions of dollars on change strategies that produce little improvement or make things worse. Mergers fail. Technology falls short of its potential. Strategies that are vital to success never wend their way into practice. In U.S. presidential elections, nearly all candidates promise change, but the winners struggle to deliver on even a fraction of their pledges.

To shrink the gap between change agents' intentions and outcomes, a voluminous body of literature has flourished. The sheer volume of change models, case studies, and prescriptive remedies is overwhelming. Some contain productive insights. Beer and Nohria (2001), for example, compare two distinct change models—a hard, top-down approach that emphasizes shareholder value (Theory E) and a softer, more participative strategy (Theory O) that targets organizational culture. Kanter, Stein, and Jick's "Big Three" model (1992) helps managers sort through the interplay of change strategies, change implementers, and change recipients. But despite growing knowledge, the same mistakes repeat themselves. It's like reading the latest books on dieting but never losing weight. The desired target is never easy to reach, and almost everyone wants change as long as they don't have to do anything differently. An old adage summarizes the predicament: Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose (The more things change, the more they stay the same; Karr, 1849).

This chapter opens by examining the innovation process at two different companies. It then moves to a multiframe analysis to show how participation, training, structural realignment, political bargaining, and symbolic rituals of letting go can help achieve more positive outcomes. It concludes with a discussion integrating the frames with John Kotter's influential analysis of the stages of change.

What makes organizational change so difficult? Comparing a typically flawed change effort with an atypical success story offers some answers.

Six Sigma at 3M: A Typical Scenario

Beginning at Motorola in 1986 and later enhanced at General Electric, Six Sigma evolved from a statistical concept to a range of metrics, methods, and management approaches intended to reduce defects and increase quality in products and services (Pande, Neuman, and Cavanagh, 2000). It became the new corporate shibboleth in the 1990s after its successful, widespread use at GE. Essentially the approach has two components, one emphasizing metrics and control and the other emphasizing systems design. It has spawned acronyms like DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) and DFSS (design for Six Sigma—by building quality in the from the start). GE executives groomed in the Six Sigma way brought the techniques with them when they moved to other corporations. One was James McNerney, who missed the chance to succeed Jack Welch as GE's CEO but was snapped up by 3M in 2001 to bring some discipline to a legendary enterprise that seemed to be losing its edge. Profit and sales growth were erratic, and the stock price had languished.

McNerney got people's attention by slashing eight thousand jobs (11 percent of the workforce), putting teeth in the performance review process, and tightening the free-flowing spending spigot. Thousands of 3M workers were trained to earn the Six Sigma title of "Black Belt." These converts pioneered company-wide Six Sigma initiatives such as boosting the tempo of production by reducing variation and eliminating pointless steps in manufacturing. The Black Belts trained rank-and-file employees as "green belts," in charge of local Six Sigma initiatives. The Black Belt elite maintained metrics that tracked both overall and "neighborhood" efforts to systematize and streamline all aspects of work—including research and development.

In the short run, McNerney's strategy paid off. Indicators of productivity improved, costs were trimmed, and the stock price soared. But Six Sigma's standardization began to intrude on 3M's historical emphasis on innovation. Prior to McNerney's arrival, new ideas were accorded almost unlimited time and funding to get started. Fifteen percent of employees' on-the-clock time was devoted to developing groundbreaking products—with little accountability. This approach had given birth to legendary products like Scotch Tape and Post-it notes.

Six Sigma systematized the research and development process. Sketchy, blue-sky projects gave way to scheduled, incremental development. Funds carried an expiration date, and progress through a planned pipeline was measured and charted. Development of new products began to wane. "The more you hardwire a company on total quality management, [the more] it is going to hurt breakthrough innovation," says Vijay Govindarajan, a management professor at Dartmouth. "The mindset that is needed, the capabilities that are needed, the metrics that are needed, the whole culture that is needed for discontinuous innovation, are fundamentally different." Art Fry, the inventor of the Post-it, agreed. "We all came to the conclusion that there was no way in the world that anything like a Post-it note would ever emerge from this new system" (Hindo, 2007, p. 9).

The lethargy ended, but the damage done, McNerney left 3M in 2005 to become the new CEO of Boeing. Fry added, "What's remarkable is how fast a culture can be torn apart. [McNerney] didn't kill it because he wasn't here long enough. But if he had been here much longer, I think he would have." George Buckley, McNerney's successor, observed in retrospect, "Perhaps one of the mistakes that we made as a company—it's one of the dangers of Six Sigma—is that when you value sameness more than you value creativity, I think you potentially undermine the heart and soul of a company like 3M" (Hindo, 2007, p. 9).

The progression of change at 3M reveals a familiar scenario: New CEO introduces modern management techniques and scores a short-term victory; political pressures and cultural resistance start to mount; CEO leaves to try again; organization licks its wounds and moves both backward and onward. In short, optimistic beginning, tumultuous middle, and controversial conclusion. Robert Nardelli, one of McNerney's contemporaries at GE, followed a similar script in his six years as Home Depot's CEO.

Changes launched from the top often aim for standardization, measurement, tightening things up, and enhancing profitability. Less often do efforts burble up from below with an aim to loosen things up and emphasize more spiritual concerns. In 2007, Microsoft took the less traveled path.

Steve Ballmer, Microsoft's CEO, was perplexed. The company's stock was slipping sideways, products were delayed, and many insiders perceived the company as "flabby, middle-aged and un-hip"—especially in contrast to Google (Conlin and Greene, 2007). The standard fix-it response would be to hire a new human resource chief to come up with a company-driven antidote to the malaise. Instead, Ballmer reached down into the ranks and promoted a maverick to rekindle the company's spirit. He picked Lisa Brummel, a product manager beloved for her unconventional ways and dress.

One of Brummel's first initiatives might seem strange to structural thinkers—she brought back the towels that had been a feature of employee locker rooms until removed to cut costs. The lost towels had become a heated subject in internal blogs, primarily as symbols of how little the company cared. Beyond helping with Seattle's chronic drizzle, the towels were a small but treasured perk of working at Microsoft. Brummel also replaced the self-service "industrial sludge" coffeemakers with Starbucks machines that fit Seattle's barista ethos.

The next target for Brummel's magic wand was Microsoft's dreaded performance review procedure. Devised by Ballmer himself, the ranking system was a zero-sum game in which employees competed for their individual shares of a limited purse. Managers could give only so many A's, even if several employees had performed exceptionally well. It was a touchy issue pitting Brummel against Ballmer, but she won and implemented a system that gave managers more discretion and tied raises and bonuses to a combination of pay grade and annual performance.

Brummel opened up communications by moving the internal "underground" blog into the public spotlight. She changed the company's office décor from institutional drab to modern chic and created a mobile medicine service to dispatch company physicians to employees' homes for emergencies. Brummel's initiatives raised morale, cut attrition, and, in many instances, one-upped Google. Brummel combined human resource, political, and symbolic ideas as a catalyst for change rather than as a barrier. Instead of taking things away or imposing something unwanted, she gave people things they welcomed.

How Frames Can Help

Comparing the stories of change at 3M and Microsoft illustrates an iron law: changes rationally conceived at the top often fail. More versatile approaches have a better chance. Organizations today face a persistent dilemma. Changes in their environment or leadership pressure them to adapt, yet the more they try to change, the more likely their performance is to deteriorate (Nickerson and Silverman, 2003; Barnett and Freeman, 2001). Ormerod (2007) argues that "things usually fail" because decision makers don't understand their environment well enough to anticipate the consequences of their actions. So they march blindly down their preferred path despite warning signs that they are headed in the wrong direction. And in studying scores of innovations, we continue to see managers whose strategies are limited because their thinking is limited to one or two cognitive lenses.

As Machiavelli observed many years ago in The Prince, "It must be realized that there is nothing more difficult to plan, more uncertain of success, or more dangerous to manage than the establishment of a new order of [things]; for he who introduces [change] makes enemies of all those who derived advantage from the old order and finds but lukewarm defenders among those who stand to gain from the new one" ([1514] 1961, p. 27).

Machiavelli's trenchant observations are as timely as ever. Think about the challenges of rebuilding Iraq. The architects of the U.S. invasion foresaw a relatively quick and painless transition to democratic stability. Instead, removing the Saddam Hussein regime opened a Pandora's box of political and symbolic issues that had been seething beneath the surface. It is much better to see quicksand before rather than after you're mired in it. The frames can help change agents see pitfalls and roadblocks ahead, thereby increasing their odds of success.

Organizational change is a complex systemic undertaking. It rarely works to retrain people without revising roles or to revamp roles without retraining. Planning without broad-based participation that gives voice to the opposition almost guarantees stiff resistance later on. Change alters power relationships and undermines existing agreements and pacts. Even more profoundly, it intrudes on deeply rooted symbolic forms, traditional ways, and customary behavior. Below the surface, the organization's social tapestry begins to unravel, threatening both time-honored traditions and prevailing cultural values and ways.

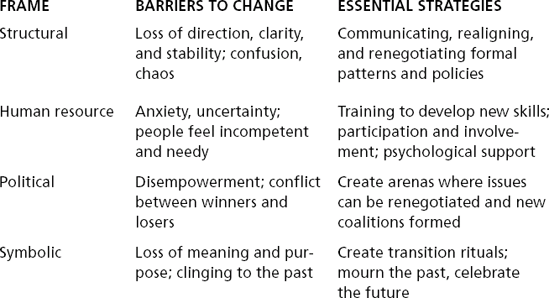

In the remainder of the chapter, we look at the human resource, structural, political, and symbolic aspects of organizational change and integrate them with Kotter's model of the change process. Exhibit 18.1 summarizes the views of major issues in change that each frame offers. The human resource view focuses on needs, skills, and participation, the structural approach on alignment and clarity, the political lens on conflict and arenas, and the symbolic frame on loss of meaning and the importance of creating new symbols and ways. Each mode of thought highlights a distinctive set of barriers and offers possibilities for making change stick.

It sounds simplistic to point out that investment in change calls for collateral outlays in training and developing active channels for employee input. Yet countless innovations falter and flop because managers neglect to spend time and money to develop needed knowledge and skills and to involve people throughout the process. The human resource department is too often an afterthought no one takes seriously.

In one large firm, for example, top management decided to purchase state-of-the-art technology. They expected a decisive competitive advantage from a 50 percent cut in cycle time from customer order to delivery. Hours of careful analysis went into crafting the strategy. The new technology was launched with great fanfare. The CEO assured a delighted sales force it would now have a high-tech competitive edge. After the initial euphoria faded, though, the sales force realized that its old methods and skills were obsolete; years of experience were useless. Veterans felt like neophytes. When the CEO heard that the sales force was shaky about the new technology, he said, "Then get someone in human resources to throw something together. You know, what's-her-name, the new vice president. That's why we hired her." A year later, the new technology had failed to deliver. The training never materialized. Input from the front lines never reached the right ears. The company's investment ultimately yielded a costly, inefficient process and a demoralized sales force. The window of opportunity was lost to the competition.

A happier example occurred in a large hospital that invested millions of dollars in a new integrated information system. The goal was to improve patient care by making updates quickly available to everyone involved in a treatment plan. Widespread involvement ensured that relevant ideas and concerns were folded into the innovative system. Terminals linked patients' bedsides to nursing stations, attending physicians, pharmacy, and other services. To ensure that the new system would work, hospital administrators created a simulation lab. Individual representatives from all groups were brought into a room and seated at terminals. Hypothetical scenarios gave them a chance to practice and work out the kinks. Many staff members, particularly physicians, needed to improve their computer skills. Coaches were there to help. Each group became its own self-help support system. Skills and confidence improved in the training session. Relationships that formed as a result of extensive involvement and participation were invaluable as the new technology went into operation.

From a human resource perspective, people have good reason to resist change. Sometimes resistance is sensible because the new methods are a management mistake that would take the organization in the wrong direction. But in any event, no one likes feeling anxious, voiceless, and incompetent. Changes in routine practice and protocol undermine existing knowledge and skills and undercut people's ability to perform with confidence and success. When asked to do something they don't understand, haven't had a voice in developing, don't know how to do, or don't believe in, people feel puzzled, anxious, and insecure. Lacking skills and confidence to implement the new ways, they resist or even engage in sabotage, awaiting the return of the good old days. Or they may comply superficially while covertly dragging their feet. Even if they try to do what they are told, the results are predictably dismal. Training, psychological support, and participation all increase the likelihood that people will understand and feel comfortable with the new methods.

Often overlooked in the training loop are the change agents responsible for promoting and guiding the change. Kotter presents a vivid example of how training can prepare people to communicate the rationale for a new order of things. A company moving to a team-based structure developed at the top was concerned about how workers and trade unions would react. To make sure people would understand and accept the changes, the managers went through an intensive training regimen: "Our twenty 'communicators' practiced and practiced. They learned the responses, tried them out, and did more role plays until they felt comfortable with nearly anything that might come at them. Handling 200 issues well may sound like too much, but we did it.... I can't believe that what we did is not applicable nearly everywhere. I think too many people wing it" (Kotter and Cohen, 2002, p. 86). Taking the time to hear people's ideas and concerns and to make sure that all involved have the talent, confidence, and expertise necessary to carry out their new responsibilities is a requisite of successful innovation.

Involvement and training will not ensure success unless existing roles and relationships are realigned to fit the new initiative. As an example, a school system created a policy requiring principals to assume a more active role in supervising classroom instruction. Principals were trained in how to observe and counsel teachers. When they set out to apply their new skills, morale problems and complaints soon began to surface. No one had anticipated how changes in principals' duties might affect teachers and impinge on existing agreements about authority. Did teachers believe it was legitimate for principals to spend time in classrooms observing and suggesting ways to improve teaching? Most important, no one had asked who would handle administrative duties for which principals no longer had time. As a result, supplies were delayed, parents felt neglected, and discipline deteriorated. By midyear, most principals had gone back to their administrative duties and were leaving teachers alone.

Change undermines existing structural arrangements, creating ambiguity, confusion, and distrust. People no longer know what is expected of them or what they can expect from others. Everyone may think someone else is in charge when, in fact, no one is. As a result of changes in health care, for example, a hospital was experiencing substantial employee turnover and absenteeism, a shortage of nurses, poor communication, and low staff morale. There were rumors of an impending effort to organize a union. A consultant's report identified several structural problems:

One set related to top management. Members of the executive committee seemed to be confused about their roles and authority. Many believed all important decisions were made (prior to the meetings) by Rettew, the hospital administrator. Many shared the perception that major decisions were made behind closed doors, and that Rettew often made "side deals" with different individuals, promising them special favors or rewards in return for support at the committee meetings. People at this level felt manipulated, confused, and dissatisfied.

Major problems also existed in the nursing service. The director of nursing seemed to be patterning her managerial style after that of Rettew.... Nursing supervisors and head nurses felt that they had no authority, while staff nurses complained about a lack of direction and openness by the nursing administration. The structure of the organization was unclear. Nurses were unaware of what their jobs were, whom they should report to, and how decisions were made [McLennan, 1989, p. 231].

As the school and hospital examples both illustrate, when things start to shift, people become unsure of what their duties are, how to relate to others, and who has authority to decide what. Clarity, predictability, and rationality give way to confusion, loss of control, and a sense that politics trumps policy. To minimize such difficulty, innovators must anticipate structural issues and work to redesign the existing architecture of roles and relationships. In some situations, this can be done informally. In others, structural arrangements need to be renegotiated more formally (through some version of responsibility charting, discussed in Chapter Five).

Change invariably creates conflict. It typically turns into a tug-of-war between innovators and traditionalists to determine winners and losers. Change almost always benefits some people while neglecting or harming others. That ensures that some individuals and groups support the change while others oppose it, sit on the fence, or become isolated. Often, clashes go underground and smolder beneath the surface. Occasionally, they burst open as eruptions of unregulated warfare.

A classic case in point comes from a U.S. government initiative to improve America's rural schools.

Such a scenario is predictable. As changes emerge, camps form: supporters, opponents, and fence-sitters. Conflict is avoided or smoothed over until it explodes in divisive battles. Coercive power, rather than legitimate authority, often determines the victor. Typically, the status quo prevails and change agents lose.

From a political perspective, conflict is natural. It is best managed through processes of negotiation and bargaining, where settlements and agreements can be hammered out. If ignored, disputes explode into street fights—no rules, anything goes. People get hurt, and scars linger for years. The alternative to street fights is arenas with rules, referees, and spectators. Arenas create opportunities to forge divisive issues into shared agreements. Through bargaining, compromises can be worked out between the status quo and innovative ideals. Welding new ideas onto existing practices is essential to successful change. One hospital administrator said, "The board and I had to learn how to wrestle in a public forum."

Mitroff (1983) describes a drug company facing competitive pressure on its branded prescription drug from generic substitutes. Management was split into three factions: one group wanted to raise the price of the drug, another wanted to lower it, and still another wanted to keep it the same but cut costs. Each group collected information, constructed models, and developed reports showing that its solution was correct. The process degenerated into a frustrating spiral. Mitroff intervened to get each group to identify major stakeholders and articulate assumptions about them. All agreed that the most critical stakeholders were physicians prescribing the drug. Each group had its own suppositions about how physicians would respond to a price change. But no one really knew. The three groups finally agreed to test their assumptions by implementing a price increase in selected markets.

The intervention worked through convening an arena with a more productive set of rules. Similarly, experimental school districts that created arenas for resolving conflict were more successful than others in bringing about comprehensive change. In the school district cited earlier, teachers reacted to administrative coercion with a power strategy of their own:

Community members initiated a group called Concerned Citizens for Education in response to a phone call from a teacher who noted that parents should be worried about what the [administrators] were doing to their children. The superintendent became increasingly occupied with responding to demands and concerns of the community group. Over time, the group joined in a coalition with teachers to defeat several of the superintendent's supporters on the school board and to elect members who were more supportive of their interests. The turnover in board membership reduced the administrator's power and authority, making it necessary to rely more and more on bargaining and negotiation strategies to promote the intended change [Deal and Nutt, 1980, p. 20].

Successful change requires an ability to frame issues politically, build coalitions, and establish arenas in which disagreements can be hammered into workable pacts. One insightful executive remarked: "We need to confront, not duck, and face up to disagreements and differences of opinions and conflicting objectives.... All of us must make sure—day in and day out—that conflicts are aired and resolved before they lead to internecine war."

In the early 1980s, America's Cola wars—a battle between Coke and Pepsi—reached a fever pitch. A head-to-head taste test called the Pepsi Challenge was making inroads in Coca-Cola's market share. In blind tests, even avowed Coke drinkers preferred Pepsi. Pepsi won narrowly in a Coke counterchallenge held at its corporate headquarters in Atlanta. Coca-Cola executives became more nervous when Pepsi stunned the industry by signing Michael Jackson to a $5 million celebrity advertising campaign. Coke struck back with one of the most startling announcements in the company's ninety-nine-year history: Old Coke would be replaced with New Coke:

Shortly before 11:00 AM [on Tuesday, April 23, 1985], the doors of the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center opened to two hundred newspaper, magazine, and TV reporters. The stage was aglow with red. Three huge screens, each solid red and inscribed with the company logo, rose behind the podium and a table draped in red. The lights were low; the music began: "We are. We will always be. Coca-Cola. All-American history." As the patriotic song filled the theater, slides of Americana flashed on the center screen—families and kids, Eisenhower and JFK, the Grand Canyon and wheat fields, the Beatles and Bruce Springsteen, cowboys, athletes, and the Statue of Liberty—and interspersed throughout, old commercials for Coke. Robert Goizueta [CEO of Coca-Cola] came to the podium. He first congratulated the reporters for their ingenuity in already having reported what he was about to say. And then he boasted, "The best has been made even better." Sidestepping the years of laboratory research that had gone into the program, Goizueta claimed that in the process of concocting Diet Coke, the company flavor chemists had "discovered" a new formula. And research had shown that consumers preferred this new one to old Coke. Management could then do one of two things: nothing, or buy the world a new Coke. Goizueta announced that the taste-test results made management's decisions "one of the easiest ever made" [Oliver, 1986, p. 132].

The rest is history. Coke drinkers overwhelmingly rejected the new product. They felt betrayed; many were outraged:

Duane Larson took down his collection of Coke bottles and outside of his restaurant hung a sign, "They don't make Coke anymore."... Dennis Overstreet of Beverly Hills hoarded 500 cases of old Coke and advertised them for $30 a case. He is almost sold out.... San Francisco Examiner columnist Bill Mandel called it "Coke for wimps."... Finally, Guy Mullins exclaimed, "When they took old Coke off the market, they violated my freedom of choice—baseball, hamburgers, Coke—they' re all the fabric of America" [Morganthau, 1985, pp. 32–33].

Even bottlers and Coca-Cola employees were aghast: "By June the anger and resentment of the public was disrupting the personal lives of Coke employees, from the top executives to the company secretaries. Friends and acquaintances were quick to attack, and once-proud employees now shrank from displaying to the world any association with the Coca-Cola company" (Oliver, 1986, pp. 166–167).

Coca-Cola rebounded quickly with Classic Coke. Indeed, the company's massive miscalculation led to one of the strangest serendipitous triumphs in marketing history. All the controversy, passion, and free publicity stirred up by the New Coke fiasco ultimately helped Coca-Cola regain its dominance in the soft drink industry. A brilliant stratagem, if anyone had planned it.

What led Coke's executives into such a quagmire? Several factors were at work. Pepsi was gaining market share. As the newly appointed CEO of Coca-Cola, Goizueta was determined to modernize the company. A previous innovation, Diet Coke, had been a huge success. Most important, Coca-Cola's revered long-time "Boss," Robert Woodruff, had just passed away. On his deathbed, he reportedly gave Goizueta his blessing for the new recipe.

In their zeal to compete with Pepsi, Coke's executives overlooked a central tenet of the symbolic frame. The meaning of an object or event can be far more powerful than the reality. Strangely, Coke's leadership had lost touch with their product's significance to consumers. To many people, old Coke was a piece of Americana. It was linked to cherished memories. Coke represented something far deeper than just a soft drink.

In introducing New Coke, company executives unintentionally announced the passing of an American symbol. Symbols create meaning, and when one is destroyed or vanishes people experience emotions akin to those at the passing of a spouse, child, old friend, or pet. When a relative or close friend dies, we feel a deep sense of loss. We harbor similar feelings when a computer replaces old procedures, a logo changes after a merger, or an old leader is replaced by a new one. When these transitions take place in the workplace rather than in a family, feelings of loss are often denied or attributed to other causes.

Any significant change in an organization may trigger two conflicting symbolic responses. The first is to keep things as they were, to replay the past. The second is to ignore the loss and plunge into the future. Individuals or groups can get stuck in either form of denial or bog down vacillating between the two.

Four years after AT&T was forced to divest its local phone operations, an executive remarked: "Some mornings I feel like I can set the world on fire. Other mornings I can hardly get out of bed to face another day." Nurses in one hospital's intensive care unit were caught in a loss cycle for ten years following their move from an old facility. Loss is an unavoidable by-product of improvement. As change accelerates, executives and employees get caught in endless cycles of unresolved grief.

In our personal lives, the pathway from loss to healing is culturally prescribed. Every culture outlines a sequence for transition rituals following significant loss: always a collective experience in which pain is expressed, felt, and juxtaposed against humor and hope. (Think of Irish actor Malachy McCourt who, as his mother lay dying, said to her distressed physician, "Don't worry, Doctor, we come from a long line of dead people.")

In many societies, the sequence of ritual steps involves a wake, a funeral, a period of mourning, and some form of commemoration. From a symbolic perspective, ritual is an essential companion to significant change. A Naval change-of-command ceremony, for example, is informally scripted by tradition. A wake is held for the outgoing commander. The mantle of command is passed to the new commander in a full-dress ceremony attended by friends, relatives, and assembled officers and sailors. The climactic moment of transition occurs with the incoming and outgoing skippers at attention facing each other. The new commander salutes and says, "I relieve you, sir." The retiring commander salutes and responds, "I stand relieved." During the ceremony, the new commander's name is posted on the unit's entrance. After a time, the old commander's face or name is displayed in a picture or plaque.

Transition rituals initiate a sequence of steps that help people let go of the past, deal with a painful present, and move into a meaningful future. The form of these rites varies widely, but they are essential to the ability to face and transcend loss. Otherwise, people vacillate between clinging to the old and rushing to the future. An effective ritual helps them let go of old ways and embrace a new beginning.

The Rebirth of Delta Corporation

Owen (1987) vividly documents these issues in his description of change at "Delta Corporation." An entrepreneur named Harry invented a product that sold well enough to support a company of thirty-five hundred people. After a successful public stock offering, the company experienced soaring costs, flattened sales, and a dearth of new products. Facing stockholder dissatisfaction and charges of mismanagement, Harry passed the torch to a new leader.

Harry's replacement was very clear about her vision: she wanted "engineers who could fly." But her vision was juxtaposed against a history of "going downhill. "A further complication was that various parts of the company were governed by distinct stories representing different Delta themes. Finance division stories exemplified the new breed of executives brought in following Harry's departure. Research and development stories varied by organizational level. At the executive level, "Old Harry" stories extolled the creative accomplishments of the former CEO. Middle management stories focused on the Golden Fleece award given monthly behind the scenes to the researcher who developed the idea with the least bottom-line potential. On the production benches, workers told of Serendipity Sam, winner of more Golden Fleece awards than anyone else, exemplar of the excitement and innovation of Harry's regime.

Across the levels and divisions, the tales clustered into two competing themes: the newcomers' focus on management versus the company's tradition of innovation. The new CEO recognized the importance of blending old and new to build a company where "engineers could fly." She brought thirty-five people from across the company to a management retreat where she surprised everyone:

She opened with some stories of the early days, describing the intensity of Old Harry and the Garage Gang (now known as the Leper Colony). She even had one of the early models of Harry's machine out on a table. Most people had never seen one. It looked primitive, but during the coffee break, members of the Leper Colony surrounded the ancient artifact, and began swapping tales of the blind alleys, the late nights, and the breakthroughs. That dusty old machine became a magnet. Young shop floor folks went up and touched it, sort of snickering as they compared this prototype with the sleek creations they were manufacturing now. But even as they snickered, they stopped to listen as the Leper Colony recounted tales of accomplishment. It may have been just a "prototype," but that's where it all began [Owen, 1987, p. 172].

After the break, the CEO divided the group into subgroups to share their hopes for the company. When the participants returned, their chairs had been rearranged into a circle with Old Harry's prototype in the center. With everyone facing one another, the CEO led a discussion, linking the stories from the various subgroups. Serendipity Sam's account of a new product possibility came out in a torrent of technical jargon:

The noise level was fierce, but the rest of the group was being left out. Taking Sam by the hand, the CEO led him to the center of the circle right next to the old prototype. There it was the old and the new—the past, present, and potential. She whispered in Sam's ear that he ought to take a deep breath and start over in words of one syllable. He did so, and in ways less than elegant, the concept emerged. He guessed about applications, competitors, market shares, and before long the old VP for finance was drawn in. No longer was he thinking about selling [tax] losses, but rather thinking out loud about how he was going to develop the capital to support the new project. The group from the shop floor ... began to spin a likely tale as to how they might transform the assembly lines in order to make Sam's new machine. Even the Golden Fleece crowd became excited, telling each other how they always knew that Serendipity Sam could pull it off. They conveniently forgot that Sam had been the recipient of a record number of their awards, to say nothing of the fact that this new idea had emerged in spite of all their rules [Owen, 1987, pp. 173–174].

In one intense event, part of the past was buried, yet its spirit was resurrected and revised to fit the new circumstances. Disparaging themes and stories were merged into a company where "engineers could fly" profitably.

Releasing a Negative Past

Many find it hard to understand how villains can hold a culture together. But negative symbols are attractive when people lack more positive glue. In such cultural voids, griping can become the predominant ritual. The new owners of a newspaper realized that their acquisition was mired in a negative past. Letting go of old tyrants and wounds was essential to a new, more positive start.

Needing something dramatic, the new owners invited all employees to an event. They arrived to a room filled with black balloons. Pictures of the reviled managers were affixed to the lid of an open coffin positioned prominently in the front. Startled employees silently took their places. The new CEO opened the ceremony: "We are assembled today to say farewell to the former owners of this newspaper. But it only seems fitting that we should say a few words about them before they leave us forever."

On cue, without prompting or rehearsal, individuals rose from their seats, came forward, and, one by one, grabbed a picture. Each then described briefly life under the sway of "the bastards," tore up the person's photograph, and threw it into the coffin. When all the likenesses had been removed, a New Orleans style group of jazz musicians filed in playing a mournful dirge. Coffin bearers marched the coffin outside. Employees followed and released the black balloons into the sky. A buffet lunch followed, festooned by balloons with the colors of the new company logo.

The CEO admitted later, "What a risk. I was scared to death. But it came off without a hitch and the atmosphere is now completely different. People are talking and laughing together. Circulation has improved. So has morale. Who would have 'thunk' it?"

The frames offer a checklist of issues that change agents must recognize and respond to. But how can they be combined into an integrated model? How does the change process move through time? John Kotter, an influential student of leadership and change, has studied both successful and unsuccessful change efforts in organizations around the world. In his book The Heart of Change (2002, written with Dan S. Cohen), he summarizes what he has learned. His basic message is very much like ours. Too many change initiatives fail because they rely too much on "data gathering, analysis, report writing, and presentations" instead of a more creative approach aimed at grabbing the "feelings that motivate useful action" (p. 8). In other words, change agents fail when they rely mostly on reason and structure while neglecting human, political, and symbolic elements.

Kotter describes eight stages that he repeatedly found in successful change initiatives:

Creating a sense of urgency

Pulling together a guiding team with the needed skills, credibility, connections, and authority to move things along

Creating an uplifting vision and strategy

Communicating the vision and strategy through a combination of words, deeds, and symbols

Removing obstacles, or empowering people to move ahead

Producing visible symbols of progress through short-term victories

Sticking with the process and refusing to quit when things get tough

Nurturing and shaping a new culture to support the emerging innovative ways

Kotter's stages depict a dynamic process moving through time, though not necessarily in a linear sequence. In the real world, stages overlap, and change agents sometimes need to cycle back to earlier phases.

Combining Kotter's stages with the four frames generates the model presented in Exhibit 18.2. The table lists each of Kotter's stages and illustrates actions that change agents might take. Not every frame is essential to each stage, but all are critical to overall success. Consider, for example, Kotter's first stage, developing a sense of urgency. Strategies from the human resource, political, and symbolic strategies all contribute. Symbolically, leaders can construct a persuasive story by painting a picture of the current challenge or crisis and emphasizing why failure to act would be catastrophic. Human resource techniques of skill building, participation, and open meetings can help to get the story out and gauge audience reaction. Behind the scenes, leaders can meet with key players, assess their interests, and negotiate or use power as necessary to get people on board.

As another example, Kotter's fifth step calls for removing obstacles and empowering people to move forward. Structurally, this is a matter of identifying rules, roles, procedures, and patterns that block progress and then working to realign them. Meanwhile, the human resource frame counsels training, support, and resources to enable people to master new behaviors. Symbolically, a few "public hangings" (for example, firing, demoting, or exiling prominent opponents) could reinforce the message. Public celebrations could honor successes and herald a new beginning.

Exhibit 18.2 is intended as an illustration, not an exhaustive plan. Every situation and change effort is unique. Creative change agents can use the ideas to stimulate thinking and spur imagination as they develop an approach that fits local circumstances.

Innovation inevitably generates four issues. First, it affects individuals' ability to feel effective, valued, and in control. Without support, training, and a chance to participate in the process, people become powerful anchors, embedded in the past, that block forward motion. Second, change disrupts existing patterns of roles and relationships, producing confusion and uncertainty. Structural patterns need to be revised and realigned to support the new direction. Third, change creates conflict between winners and losers—those who benefit from the new direction and those who do not. This conflict requires creation of arenas where the issues can be renegotiated and the political map redrawn. Finally, change creates loss of meaning for recipients of the change. Transition rituals, mourning the past, and celebrating the future help people let go of old attachments and embrace new ways of doing things. Kotter's model of successive change includes eight stages. Integrated with the frames, it offers a well-orchestrated, integrated design for responding to needs for participative learning, realignment, negotiation, and grieving.