Larry Summers took the helm as president of Harvard in 2001. An economist and former U.S. treasury secretary, Summers concluded that the venerable university needed an overhaul. From the president's office, he issued a series of authoritative new directives. He attacked the undergraduate grading system, in which half of the students received A's and 90 percent graduated with honors. He stiffened standards for awarding tenure, encouraged more foreign study, and asked faculty (especially senior professors) to spend more time with students. He stepped across curricular boundaries to call for an emphasis on educational reform and more interdisciplinary courses. He proposed a center for medicine and science to encourage more applied research. Finally, he announced a bold move to build an additional campus across the Charles River to house new growth and development. Summers's initiatives aimed to tighten Harvard's famously decentralized structure and to imbue the president's office with more clout.

How did his plans pan out? Prior experience with restructuring teaches that a crash was likely, and, in this instance, it was a big one. Summers was forced out after the shortest term for a Harvard president in more than a century.

Major initiatives to redesign structure and processes have often proved neither durable nor beneficial. Moving from designing a structure to putting all the parts in place and satisfying every interested party is difficult and hazardous. The attempt after the 9/11 attacks to bring related agencies under the Homeland Security umbrella provides another example of the perils of restructuring. We can get an idea of the effects of this attempt by looking at one organization—the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Before 9/11, FEMA was an autonomous operation. Its main goal was to respond to domestic disasters caused by hurricanes, earthquakes, and other whims of Mother Nature. FEMA was created in 1979 by a stroke of President Jimmy Carter's official pen. It was an effort to integrate separate emergency agencies—hurricane, earthquake, flood—under a single authority. The hitch was that the blend also included Mount Weather, a super-secret national counterespionage group that was housed in separate quarters, replete with guards and other accoutrements shrouding a clandestine operation. This self-styled elite dismissed their colleagues in the rest of FEMA as a "bunch of weenies who went out and chased storms" (Cooper and Block, 2006, p. 55). In fact, FEMA was a two-headed agency. Structurally, as a disaster relief agency, it was itself a disaster, provoking an insider's comment, "How can you help others when you can't even take care of yourself?" (p. 56).

Enter James Lee Witt, a political appointee tapped to head FEMA in 1993, who promised to remake the agency into an integrated organization capable of delivering the goods when disaster struck. He envisioned catastrophes as political opportunities to showcase taxpayers' dollars at work. One of his first actions was to restructure FEMA to focus on disaster relief rather than splitting its mission to encompass national security. He also developed the agency's role in preparing for rather than just responding to national tragedies.

FEMA demonstrated its new configuration in responding successfully to earthquakes in Seattle and in Northridge, California, as well as other national disasters of the new millennium. But after September 11, 2001, terrorism rather than national disasters topped the federal agenda. FEMA was folded into a new agency, the Department of Homeland Security. Tom Ridge was appointed to head the mix of diverse, previously independent operations. The overarching goal: stop terrorism.

Structurally, the change gave FEMA another reporting level and left its funding for disaster relief vulnerable to the new emphasis on terrorism. The flaws in this arrangement became evident when Hurricane Katrina scored a bull's-eye on New Orleans. FEMA's response to the unparalleled disaster sometimes looked like an episode of the Keystone Kops or the Three Stooges. Who was in charge, who reported to whom, and basic logistical decisions appeared more happenstance than planned. More could be learned from CNN than from the official chain of command.

In the usual political blame game, FEMA's head, Michael Brown, took the hit. But the real culprit was not an individual. It was a restructuring plan that didn't work out. The core assumptions of the structural frame were overlooked or ignored. The costs in property damage and human lives were enormous, and the reputation of a previously successful government agency was tarnished.

Reorganizing, or restructuring, is a powerful but high-risk approach to improvement. An organization's structure at any moment represents its resolution of an enduring set of basic tensions or dilemmas. We begin this chapter by describing these dilemmas. Then, drawing on the work of Henry Mintzberg and Sally Helgesen, we describe two unique views of the alternatives organizations may consider in aligning structure with mission and environment. We conclude with several case examples illustrating both opportunities and challenges managers encounter when attempting to create a more workable structural design.

Finding a satisfactory system of roles and relationships is an ongoing, universal struggle. Managers rarely face well-defined problems with clear-cut solutions. Instead, they confront enduring structural dilemmas, tough trade-offs without easy answers.

Differentiation Versus Integration

The tension between allocating work and coordinating sundry efforts creates a classic dilemma, as we saw in Chapter Three. The more complex a role structure (lots of people doing many different things), the harder it is to sustain a focused, tightly coupled enterprise. Think about the challenge facing Larry Summers as he tried to bring a higher level of coordination to a highly decentralized university. As complexity grows, organizations need more sophisticated—and more costly—coordination strategies. Rules, policies, and commands have to be augmented by lateral strategies.

Gap Versus Overlap

If key responsibilities are not clearly assigned, important tasks fall through the cracks. Conversely, roles and activities can overlap, creating conflict, wasted effort, and unintended redundancy. A patient in a prestigious teaching hospital, for example, called her husband and pleaded with him to rescue her before she went crazy. At night, she couldn't sleep because hospital staff kept waking her up, often to repeat what someone else had already done. Conversely, when she wanted something, her call button rarely produced any response.

As we have seen, the new cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security, created in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, was intended to reduce gaps and overlaps among the many agencies responsible for responding to domestic threats. Activities incorporated into the new department included immigration, border protection, emergency management, and intelligence analysis. Yet, as noted in Chapter One, the two most prominent antiterrorism agencies, the FBI and the CIA—with their long history of mutual gaps, overlaps, and bureaucratic squabbling—remained separate and outside the new agency (Firestone, 2002).

Underuse Versus Overload

If employees have too little work, they become bored and get in other people's way. In one physician's office, for example, members of the clerical staff were able to complete most of their tasks during the morning. After lunch, they filled their time talking to family and friends. As a result, the office's telephone lines were constantly busy, making it difficult for patients to ask questions and schedule appointments. Meanwhile, nurses were swamped with clients and routine paperwork. Too busy for informal talk with patients, they were often brusque and curt. Patients complained about impersonal care. A better structural balance was accomplished by reassigning many of the nurses' clerical duties to office staff.

Lack of Clarity Versus Lack of Creativity

If employees are unclear about what they are supposed to do, they often tailor their roles around personal preferences instead of systemwide goals, frequently leading to trouble. Most McDonald's customers are not seeking novelty and surprise in their burgers and fries. But when responsibilities are overdefined, people conform to prescribed roles and protocols in "bureaupathic" ways. They rigidly follow job descriptions regardless of how much the service or product suffers. "You lost my bag!" an angry passenger shouted, confronting an airline manager. The manager's response was to inquire, "How was the flight?" "I asked about my bag," the passenger said. "That's not my job," the manager replied. "See someone in baggage claim." The passenger did not leave a happy customer.

Excessive Autonomy Versus Excessive Interdependence

When individuals or groups are too autonomous, people often feel isolated. Schoolteachers working in self-contained classrooms and rarely seeing other adults may feel lonely and unsupported. Yet efforts to create closer teamwork have repeatedly run aground because of teachers' difficulties in working together. In contrast, if units and roles are too tightly linked, people are distracted from work and waste time on unnecessary coordination. IBM lost an early lead in the personal computer business in part because new initiatives required so many approvals—from levels and divisions alike—that new products were overdesigned and late to market. Hewlett-Packard's ability to innovate in the late 1990s was hindered by the same problem.

Too Loose Versus Too Tight

A critical structural challenge is how to hold an organization together without holding it back. If structure is too loose, people go their own way or get lost, with little sense of what others are doing. Structures that are too tight stifle flexibility and cause people to spend much of their time trying to beat the system.

We can see some of the perils of too loose a structure in the former accounting firm Andersen Worldwide, indicted in 2002 for its role in the Enron scandal. Andersen's Houston office shredded documents and altered memos to cover up its role in Enron's questionable accounting procedures. At its Chicago headquarters, Andersen had an internal audit team, the Professional Standards Group, which was charged with reviewing the work of regional offices. But unlike other big accounting firms, Andersen let frontline partners closest to the clients overrule its internal audit team. This loose control permitted local discretion, which was a selling point to customers, but it came back to haunt the firm. The lax controls created a situation where "the rainmakers were given the power to overrule the accounting nerds" (McNamee and Borrus, 2002, p. 33).

The opposite problem is common in managed health care. Medical decisions are reviewed by insurance companies, giving clerks far removed from patient's bedside the authority to approve or deny treatment. Many physicians lament spending more time talking on the phone with insurance representatives than seeing patients. As a result of these tight controls, insurance providers sometimes deny treatments that physicians might see as urgent. In one case, a hospital-based psychologist diagnosed an adolescent as a likely perpetrator of sexual assault. The insurer questioned the diagnosis and denied hospitalization. The next day, the teenager raped a five-year-old girl.

Goalless Versus Goalbound

In some situations, few people know what the goals are; in others, people cling to goals long after they have become irrelevant or outmoded. That spells trouble unless an organization can find or invent a substitute. In the sixties, for example, polio was virtually eradicated by new vaccines. This eliminated the goal of the March of Dimes organization, which for years championed finding a cure for the crippling disease. The organization chose to shift its purpose to focus on preventing birth defects.

Irresponsible Versus Unresponsive

If people abdicate their responsibilities, performance suffers. However, adhering too rigidly to policies or procedures can be equally harmful. In public agencies, "street-level bureaucrats" (Lipsky, 1980) who deal with the public are often asked, "Could you do me this favor?" or "Couldn't you bend the rules a little bit in this case?" Turning down every request, no matter how reasonable, alienates the public and perpetuates images of bureaucratic rigidity and red tape. But agency workers who are too accommodating create problems of inconsistency and favoritism.

Structural design rarely starts from scratch. Managers search for options among the array of possibilities drawn from their accumulated wisdom or the experiences of others. Abstract templates and frameworks can offer food for thought. Henry Mintzberg and Sally Helgesen offer two conceptions of structural possibilities.

Mintzberg's Fives

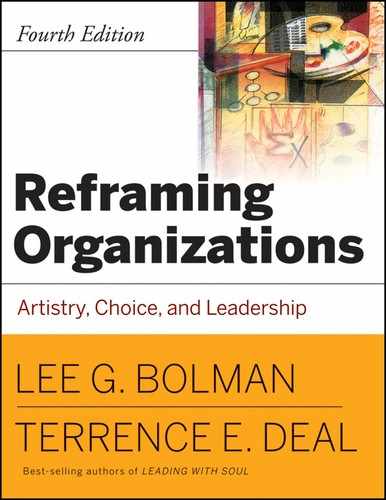

As the two-dimensional lines and boxes of a traditional organization chart have become increasingly archaic, students of organizational design have developed a variety of new structural images. One influential example is Mintzberg's five-sector "logo," depicted in Exhibit 4.1. Mintzberg's chief contribution is clustering various functions into groupings and showing their relative size and clout in response to different missions and external challenges. His schema does not provide details. It is a rough atlas of the structural terrain that helps managers get their bearings. It assists in sizing up the lay of the land before assembling a structure that conforms to the surroundings.

At the base of Mintzberg's image is the operating core, consisting of people who perform essential work. The core is made up of workers who produce or provide products or services to customers or clients: teachers in schools, assembly-line workers in factories, physicians and nurses in hospitals, and flight crews in airlines.

Directly above the operating core is the administrative component: managers who supervise, coordinate, control, and provide resources for the operators. School principals, factory foremen, and echelons of middle management fulfill this role. At the top of Mintzberg's figure, senior managers in the strategic apex track current developments in the environment, determine the mission, and shape the grand design. In school systems, the strategic apex includes superintendents and school boards. In corporations, the apex houses the board of directors and senior executives.

Two more components sit alongside the administrative component. The technostructure houses specialists, technicians, and analysts who standardize, measure, and inspect outputs and procedures. Accounting and quality control departments in industry, audit departments in government agencies, and flight standards departments in airlines perform such technical functions.

The support staff performs tasks that support or facilitate the work of others throughout the organization. In schools, for example, the support staff includes nurses, secretaries, custodians, food service workers, and bus drivers. These people often wield influence far greater than their station would suggest.

From this basic blueprint, Mintzberg (1979) derived five structural configurations: simple structure, machine bureaucracy, professional bureaucracy, divisionalized form, and adhocracy. Each creates its unique set of management challenges.

Simple Structure Most businesses begin as simple structures with only two levels: the strategic apex and an operating level (see Exhibit 4.2). Coordination is accomplished primarily through direct supervision and oversight, as in a small mom-and-pop operation. Mom or pop constantly monitors what is going on and exercises total authority over daily operations. William Hewlett and David Packard began their business in a garage, as did Apple Computer's Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak; General Electric had its humble beginnings in Thomas Edison's laboratory. The virtues of simple structure are flexibility and adaptability; one or two people control the entire operation. But virtues can become vices. Authorities block as well as initiate change, and they punish capriciously as well as reward handsomely. A boss too close to day-to-day operations is easily distracted by immediate problems, neglecting long-range strategic issues.

When a start-up company grows in size, a simple structure struggles to manage the accompanying complexity. Mintzberg's schema offer alternative possible routes, such as moving toward a machine or professional bureaucracy, or evolving into a divisionalized structure.

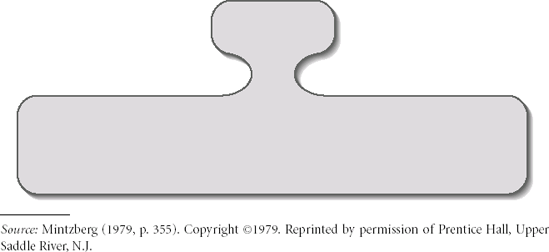

Machine Bureaucracy McDonald's is a classic machine bureaucracy. Important decisions are made at the strategic apex; day-to-day operations are controlled by managers and standardized procedures. Machine bureaucracies have large support staffs and a sizable technostructure, with many layers between the apex and operating levels (see Exhibit 4.3).

For routine tasks, such as making hamburgers and manufacturing automotive parts, a machinelike operation is both efficient and effective. A key challenge is how to motivate and satisfy workers in the operating core. People tire quickly of repetitive work and standardized procedures. Yet offering too much creativity and personal challenge in, say, a McDonald's outlet could undermine consistency and uniformity—two keys to the company's success.

Like other machine bureaucracies, McDonald's deals constantly with tension between local managers and headquarters. Middle managers are heavily influenced by local concerns and tastes. Top executives, aided by analysts armed with computer printouts, rely more on generic and abstract information and pursue corporation-wide concerns. As a result, a solution from the top may not always match the needs of individual units. Faced with declining sales and market share, McDonald's introduced a new food preparation system in 1998 under the marketing banner "Made for you." CEO Jack Greenberg was convinced the new cook-to-order system would produce the fresher, tastier burgers the company needed to get back on the fast track. But franchisees soon complained that the new system led to long lines and frustrated customers. Unfazed by the criticism, Greenberg invited a couple of skeptical financial analysts to flip burgers at a McDonald's outlet in New Jersey so they could see firsthand that the concerns were unfounded. The experiment backfired. The analysts concluded that the system was too slow and decided to pass on the stock (Stires, 2002). Greenberg was replaced at the end of 2002.

Beginning with the precepts of scientific management in the early twentieth century, recurring efforts have been made to improve public schools by getting them to work more like machine bureaucracies in which teachers are the production workers. The initiatives have included "teacher-proof" curricula, incentive pay schemes, and the use of test scores or yearly performance indicators to measure how well a school is doing. Teachers, in contrast, see themselves as professionals who need sufficient autonomy to use their experience and judgment in finding the best way for students to learn. They often prefer to work in an organization that mirrors another of Mintzberg's types, the professional bureaucracy.

Professional Bureaucracy Harvard University affords a glimpse into the inner workings of a professional bureaucracy (see Exhibit 4.4). Its operating core is large relative to its other structural parts, particularly the technostructure. Each individual school, for example, has its own local approach to teaching evaluations; there is no university-wide profile developed by analysts. Few managerial levels exist between the strategic apex and the professors, creating a flat and decentralized profile.

Control relies heavily on professional training and indoctrination. Professionals are insulated from formal interference, freeing them to apply their expertise. Freeing highly trained experts to do what they do best produces many benefits but leads to challenges of coordination and quality control. Tenured professors, for example, are largely immune from formal sanctions. As a result, universities have to find other ways to deal with incompetence and irresponsibility.

A professional bureaucracy responds slowly to external change. Waves of reform typically produce little impact because professionals often view any change in their surroundings as an annoying distraction. The result is a paradox: individual professionals may strive to be at the forefront of their specialty, while the institution as a whole changes at a glacial pace. Professional bureaucracies regularly stumble when they try to exercise greater control over the operating core; requiring Harvard professors to follow standard teaching methods might do more harm than good.

In his efforts to achieve greater control over Harvard's fractious faculty, new president Larry Summers quickly ran into predictable challenges of a professional bureaucracy. In one famous case, he suggested that superstar African American studies professor Cornel West redirect his scholarly efforts. Summers's advice was given in private, but West's pique made the front page of the New York Times. Summers's profuse public apologies failed to deter the offended professor from decamping to Princeton. In professional bureaucracies, struggles between the strategic apex and the operating core are often won by the professionals, who are more tightly bonded to their field than to any specific institution. This is a lesson hospital administrators learn quickly in their dealings with physicians.

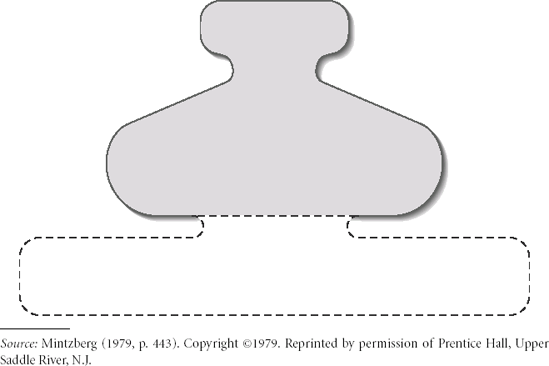

Divisionalized Form In a divisionalized organization (see Exhibit 4.5), the bulk of the work is done in quasi-autonomous units, as with free-standing campuses in a multi-campus university, areas of expertise in a large multi-specialty hospital, or independent businesses in a Fortune 500 firm (Mintzberg, 1979). Hewlett-Packard, for example, created separate divisions organized around different products and engineering expertise. Its printer division cornered the market to become a financial success, while its computer division struggled against intense competition. But the divisionalized structure gave the computer division time, resources, and a powerful brand that it leveraged to transform itself from also-ran to market leader.

One of the oldest businesses in the United States, Berwind Corporation, houses divisions in business sectors as diverse as manufacturing, financial services, real estate, and land management. Each division serves a distinct market and supports its own functional units. Division presidents are accountable to the corporate office in Philadelphia for specific results: profits, sales growth, and return on investment. As long as they deliver, divisions have relatively free rein. Philadelphia manages the strategic portfolio and allocates resources on the basis of its assessment of market opportunities.

Divisionalized structure offers economies of scale, resources, and responsiveness while controlling economic risks, but it creates other tensions. One is a cat-and-mouse game between headquarters and divisions. Headquarters wants oversight, while divisional managers try to evade corporate control:

Our top management likes to make all the major decisions. They think they do, but I've seen one case where a division beat them. I received ... a request from the division for a chimney. I couldn't see what anyone would do with a chimney .... [But] they've built and equipped a whole plant on plant expense orders. The chimney is the only indivisible item that exceeded the $50,000 limit we put on plant expense orders. Apparently they learned that a new plant wouldn't be formally received, so they built the damn thing" [Bower, 1970, p. 189].

Another risk in the divisionalized form is that headquarters may lose touch with operations. (As one manager put it, "Headquarters is where the rubber meets the air.") Divisionalized enterprises become unwieldy unless goals are measurable and reliable vertical information systems are in place (Mintzberg, 1979).

Adhocracy Adhocracy is a loose, flexible, self-renewing organic form tied together mostly through lateral means (see Exhibit 4.6). Usually found in a diverse, freewheeling environment, adhocracy functions as an "organizational tent," exploiting benefits that structural designers traditionally regarded as liabilities: "Ambiguous authority structures, unclear objectives, and contradictory assignments of responsibility can legitimize controversies and challenge traditions. Incoherence and indecision can foster exploration, self-evaluation, and learning" (Hedberg, Nystrom, and Starbuck, 1976, p. 45). Inconsistencies and contradictions in an adhocracy become paradoxes where a balance between opposites protects an organization from falling into an either-or trap.

Ad hoc structures are most often found in conditions of turbulence and rapid change. Examples are advertising agencies, think-tank consulting firms, and the recording industry. In the 1970s and 1980s, Digital Equipment was a well-known pioneer of adhocracy: "In many ways [DEC] is a big company in small company clothes. It doesn't believe much in hierarchy, rule books, dress codes, company cars, executive dining rooms, lofty titles, country club memberships, or most trappings of 'corporacy.' It doesn't even have assigned parking spots. Only the top half-dozen executives have sizable offices. Everyone else at the company headquarters in Maynard, Mass., makes do with dinky doorless cubicles" (Machan, 1987, p. 154).

Digital's structural arrangements helped it become the world leader in minicomputers. But the structural design became a problem when the market shifted toward personal computers, where aggressive new competitors like Compaq and Dell were dominant. "They flew so high and crashed so hard," said one observer, because "at DEC, the internal mattered so much. They spent their lives playing with each other" (Johnson, 1996, p. F11). The strength of Digital's adhocracy, a flowering of local creativity, became a liability when the company needed a timely organization-wide change in direction.

Helgeson's Web of Inclusion

Mintzberg's five-sector imagery adds a new dimension to the conventional line-staff organization chart but still retains much of the traditional portrait of structure as a clear-cut, top-down pyramid. Helgesen argues that the idea of hierarchy is primarily a male-driven depiction, quite different from structures created by female executives: "The women I studied had built profoundly integrated and organic organizations in which the focus was on nurturing good relationships; in which the niceties of hierarchical rank and distinction played little part; and in which lines of communication were multiplicitous, open, and diffuse. I noted that women tended to put themselves at the center of their organizations rather than at the top, thus emphasizing both accessibility and equality, and that they labored constantly to include people in their decision-making" (Helgesen, 1995, p. 10).

Helgesen coined the expression "web of inclusion" to portray an organic architectural form more circular than hierarchical. The web builds from the center out. Its architect works much like a spider, spinning new threads of connection and reinforcing existing strands. The web's center and periphery are interconnected; action in one place ripples across the entire configuration, forming "an interconnected cosmic web in which the threads of all forces and events form an inseparable net of endless, mutually conditioned relations" (Fritjof Capra, quoted in Helgesen, 1995, p. 16). As a consequence, weaknesses in either the center or the periphery of the web undermine the strength of the natural network.

One of the most famous and important examples of web organization is "Linux, Inc.," the loose organization of individuals and companies that has formed around Linus Torvalds, the creator of the open-source operating system Linux, which has become Microsoft Windows's biggest competitor on servers and desktops. "Linux, Inc." is anything but a traditional company: "There's no headquarters, no CEO, and no annual report. And it's not a single company. Rather, it's a cooperative venture in which employees at about two dozen companies, along with thousands of individuals, work together to improve Linux software.... The Linux community, Torvalds says, is like a huge spider web, or better yet, multiple spider webs representing dozens of related open-source projects. His office is' near where those webs intersect'" (Hamm, 2005).

The freewheeling web form encounters increasing challenges as an organization gets bigger. When Meg Whitman become CEO of Internet phenomenon eBay in 1998, she joined an organization of fewer than fifty employees configured in an informal web surrounding founder Pierre Omidyar. One of her first steps was to set up appointments with her new staff. She was surprised to learn that scheduled meetings were a foreign concept in a company where no one kept a calendar. Omidyar had built a company with a strong culture and powerful sense of community but no explicit strategy, no regular meetings, no marketing department, and almost no other identifiable structural elements. Despite the company's phenomenal growth and profitability, Whitman concluded that it was in danger of imploding without more structure and discipline. Omidyar agreed. He had worked hard to recruit Whitman because he believed she brought the big-company management experience that eBay needed to keep growing (Hill and Farkas, 2000).

Sooner or later, internal or external changes force every structure to remodel. When the time for restructuring comes, managers need to take account of tensions specific to each structural configuration. Consultants and managers often apply general principles and specific answers without recognizing key differences across architectural forms. Reshaping an adhocracy, for example, is radically different from restructuring a machine bureaucracy, and reweaving a web is a far cry from nudging a professional bureaucracy. Falling victim to the one-best-system or one-size-fits-all mentality is a surefire route to disaster. But the comfort of a well-defined prescription lulls too many managers into a temporary comfort zone. The iceberg looming ahead falls outside their field of vision.

Mintzberg's imagery suggests general principles to guide restructuring across a range of circumstances. Each major component of his model exerts its own pressures. Restructuring triggers a multidirectional tug-of-war that eventually determines the shape of the structure. Unless various pushes and pulls are acknowledged and managed effectively, the result may be a catastrophe.

The strategic apex—top management—tends to exert centralizing pressures. Through commands, rules, or less obtrusive means, top managers continually try to develop a unified mission or strategy. Deep down, they long for a simple structure they can control. By contrast, middle managers resist control from the top and tend to pull the organization toward balkanization. Navy captains, school principals, department heads, and bureau chiefs become committed to their own domain and seek to protect and enhance their unit's parochial interests. Tensions between centripetal forces from the top and centrifugal forces from middle management are especially prominent in divisionalized structures but are critical issues in any restructuring effort.

The technostructure exerts pressures to standardize; analysts want to measure and monitor the organization's progress against well-defined criteria. Depending on the circumstances, they counterbalance (or complement) top administrators, who want to centralize, and middle managers, who seek greater autonomy. Technocrats feel most at home in a machine bureaucracy.

The support staff pulls in the direction of greater collaboration. Its members usually feel happiest when authority is dispersed to small work units. There they can influence, directly and personally, the shape and flow of everyday decisions. They prefer adhocracy. Meanwhile, the operating core seeks to control its own destiny and minimize influence from the other components. Its members often look outside—to a union or to their professional colleagues—for support.

Attempts to restructure must acknowledge the natural tensions among various components. Depending on the configuration—machine bureaucracy, professional bureaucracy, simple structure, divisionalized form, or adhocracy—each component has more or less influence on the final outcome. In a simple structure, the boss has the edge. In machine bureaucracies, the technostructure and strategic apex possess the most clout. In professional bureaucracies, chronic conflict between administrators and professionals is the dominant tension, while members of the technostructure play an important role in the wings. In the adhocracy, a variety of actors can play a pivotal role in shaping the emerging structural patterns.

Beyond internal negotiations lurks a more crucial issue. A structure's workability ultimately depends on its fit with the organization's environment and technology. Natural selection weeds out the field, determining survivors and victims. The major players must negotiate a structure that meets the needs of each component and still works in the organization's environment.

Why Restructure?

Restructuring is a challenging process that consumes time and resources with no guarantee of success. Organizations typically embark on that path when they feel compelled to respond to major problems or opportunities. Various pressures can lead to that conclusion:

The environment shifts. At American Telephone & Telegraph, a mandated shift from regulated monopoly to a market with multiple competitors required a massive reorganization of the Bell System that played out over decades. When AT&T split off its local telephone companies into regional "Baby Bells," few anticipated that eventually one of the children (Southwest Bell) would swallow up the parent and appropriate its identity.

Technology changes. The aircraft industry's shift from piston to jet engines profoundly affected the relationship between engine and airframe. Some established firms faltered because they underestimated the complexities; Boeing rose to lead the industry because it understood them (Henderson and Clark, 1990).

Organizations grow. Digital Equipment thrived with a very informal and flexible structure during the company's early years, but the same structure produced major problems when it grew into a multibillion-dollar corporation.

Leadership changes. Reorganization is often the first initiative of new leaders. It is a way for them to try to put their stamp on the organization, even if no one else sees a need to restructure.

Miller and Friesen (1984) studied a sample of successful as well as troubled firms undergoing structural change and found that those in trouble typically fell into one of three configurations:

The impulsive firm: A fast-growing organization, controlled by one individual or a few top people, in which structures and controls have become too primitive and the firm is increasingly out of control. Profits may fall precipitously, and survival may be at stake. Many once-successful entrepreneurial organizations stumble at this stage; they have failed to evolve beyond their simple structure.

The stagnant bureaucracy: An older, tradition-dominated organization with an obsolete product line. A predictable and placid environment has lulled everyone to sleep, and top management is slavishly committed to old ways. Information systems are too primitive to detect the need for change, and lower-level managers feel ignored and alienated. Many old-line corporations and public bureaucracies fit this group of faltering machine bureaucracies.

The headless giant: A loosely coupled, divisional organization that has turned into a collection of feudal baronies. The administrative core is weak, and most of the initiative and power resides in autonomous divisions. With little strategy or leadership at the top, the firm is adrift. Collaboration is minimal because departments compete for resources. Decision making is reactive and crisis-oriented. WorldCom is a recent example of how bad things can get in this situation. CEO Bernie Ebbers built the company rapidly from a tiny start-up in Mississippi to a global telecommunications giant through some sixty-five acquisitions. But "for all its talent in buying competitors, the company was not up to the task of merging them. Dozens of conflicting computer systems remained, local network systems were repetitive and failed to work together properly, and billing systems were not coordinated. 'Don't think of WorldCom the way you would of other corporations,' said one person who has worked with the company at a high level for many years. 'It's not a company, it's just a bunch of disparate pieces. It's simply dysfunctional'" (Eichenwald, 2002c, p. C4).

Miller and Friesen (1984) found that even in troubled organizations, structural change is episodic: long periods of little change are followed by brief episodes of major restructuring. Organizations are reluctant to make major changes because a stable structure reduces confusion and uncertainty, maintains internal consistency, and protects the existing equilibrium. The price of stability is a structure that grows increasingly misaligned with the environment. Eventually, the gap gets so big that a major overhaul is inevitable. Restructuring, in this view, is like spring cleaning: we accumulate debris over months or years until we are finally forced to face up to the mess.

Making Restructuring Work: Three Case Examples

In this section, we look at three case examples of restructuring. We focus particularly on examples of reengineering, which rose to prominence in the 1990s as an umbrella concept for emerging trends in structural thinking. Hammer and Champy promised a revolution in how organizations were structured: "When a process is reengineered, jobs evolve from narrow and task oriented to multidimensional. People who once did as they were instructed now make choices and decisions on their own instead. Assembly-line work disappears. Functional departments lose their reason for being. Managers stop acting like supervisors and behave more like coaches. Workers focus more on customers' needs and less on their bosses' whims. Attitudes and values change in response to new incentives. Practically every aspect of the organization is transformed, often beyond recognition" (1993, p. 65).

The process of reengineering and the results it produces vary significantly. As Champy admitted in his follow-up book, Reengineering Management (1995), "Reengineering is in trouble." He attributed the shortfall to flaws in senior management thinking. Essentially, for reengineering to succeed, managers need to be rewired. Some reengineering initiatives have indeed been catastrophic, a notorious example being the long-haul bus company, Greyhound Lines. As the company came out of bankruptcy in the early 1990s, a new management team announced a major reorganization, with sizable cuts in staffing and routes and development of a new, computerized reservation system. The new initiative played well on Wall Street, where the company's stock soared, but it fared very poorly on Main Street as both customer service and the new reservations system collapsed. Rushed, underfunded, and insensitive to both employees and customers, it was a textbook example of how not to restructure. Eventually, Greyhound's stock crashed, and management was forced out. One observer noted wryly, "They reengineered that business to hell" (Tomsho, 1994, p. A1). Across many organizations, reengineering was a cover for downsizing the workforce.

But while few in number compared to disasters, there have also been examples of notable restructuring success. Here we discuss three of them, drawn from different eras and industries. The first, from Citibank, dates back to the 1970s, well before the term reengineering was applied to structural change.

The revamp of the Citibank back room demonstrates again the value of managerial imagination. The basic concepts behind restructuring the back room were not new. The change from a functional bureaucracy to a divisionalized form first occurred in the 1920s at General Motors and DuPont. The key imaginative leap was to apply the concept of a divisionalized organization to the back room of a bank.

The Citibank restructuring was strongly driven from the top down and focused primarily on internal efficiencies. This has been true of many, but by no means all, reengineering efforts.

Principles of Successful Structural Change

The proportion of reengineering failures to successes is high. The Citibank, Kodak, and Beth Israel efforts succeeded by following several basic principles of successful structural change:

The change architects developed a new conception of the organization's goals and strategies.

They carefully studied the existing structure and process so that they fully understood how things worked. Many efforts at structural change fail because they start from an inadequate picture of current roles, relationships, and processes.

They designed the new structure in response to changes in goals, technology, and environment.

Finally, they experimented as they moved along, retaining things that worked and discarding those that did not.

At a given moment, an organization's structure represents its best effort to align internal workings with outside concerns. Simultaneously, managers work to juggle and resolve enduring organizational dilemmas: Are we too loose, or too tight? Are employees underworked, or overwhelmed? Are we too rigid, or do we lack standards? Do people spend too much or too little time harmonizing with one another? Structure represents a resolution of contending claims from various groups.

Mintzberg differentiates five major components in organizational structure: strategic apex, middle management, operating core, technostructure, and support staff. These components configure in unique designs: machine bureaucracy, professional bureaucracy, simple structure, divisionalized form, and adhocracy. Helgesen adds a less hierarchical model, the web of inclusion.

Changes eventually require some form of structural adaptation. Restructuring or reengineering is a logical but high-risk response. In the short term, it invariably produces confusion, resistance, and even a decline in success. In the long run, success depends on how well the new model aligns with environment, task, and technology. It also hinges on the route for putting the new structure in place. Effective restructuring requires both a fine-grained, microscopic assessment of typical problems and an overall, topographical sense of structural al options.