Conclusion

The conclusion of this book is divided into two parts. The first part (section C.1) makes it possible to reproduce in a more summative form the progression of each chapter and the overall purpose. The second part (section C.2) aims to integrate all the elements presented in the book into a proposed framework for the analysis of HR quantification tools.

C.1. Summary of the book

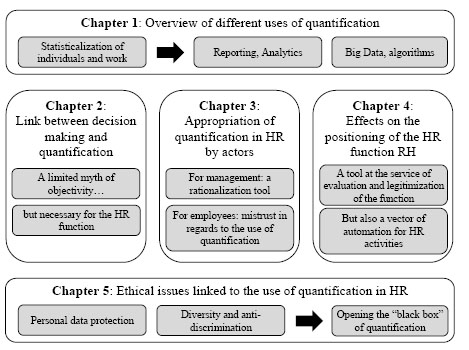

The objective of this book was to provide an overview of the uses of HR quantification, but also of the different discourses and theories held on these uses and tools (Figure C.1).

Thus, the first chapter was devoted to three main uses of quantification. The first element of this chapter was based on a reflection on the statisticalization of reality underlying the quantification tools: quantification of the human being (aptitude tests or performance evaluation) and of work (job classification, for example). Then, the next two elements were articulated around more precise tools. Thus, reporting and dashboards were mentioned as the most common first use of HR quantification, followed by HR analytics – i.e. the use of more advanced statistical techniques to better understand HR phenomena. It was pointed out that these two uses were part of an evidence-based management (EBM) approach, which was more assertive for HR analytics. Then, the increasing use of algorithms and the emergence of the notion of “Big Data” were the subject of the last section of the chapter. The aim has been to give concrete examples of this third use of quantification, but also to discuss the specificities of Big Data in the HR field and in relation to reporting and dashboards.

Figure C.1. Summary of the work

Chapters 2–4 were devoted to specific questions on the relationship between quantification and HR. For example, Chapter 2 focused on the links between HR decision-making and quantification. The chapter began by highlighting the myth of objectivity and its limitations, and then highlighting the importance of objectivity for the HR function, which probably explains why this myth is maintained within organizations, despite the limitations outlined. The chapter then addressed two important developments for both statistical science and the HR function: the use of quantification for customization and prediction purposes.

Chapter 3 then examined the appropriation of HR quantification tools by different actors in the organization. It thus made a very schematic distinction between management and HR, on the one hand, and employees and their representatives, on the other hand. Thus, it highlighted the fact that since the beginning of the 20th Century, management has regularly been able to see quantification as a tool for managerial rationalization. Three examples of this link between quantification and managerial rationalization were studied in chronological order of their appearance: bureaucracy, New Public Management and algorithmic management. On the other hand, the following sections of the chapter were devoted to the potential difficulties of appropriation of these tools by employees and their representatives. The obstacles have thus been highlighted to the provision of personal data by employees, but also their mistrust of disembodied decision making, based essentially on a quantification that may sometimes seem opaque because of its technical nature.

Chapter 4 then raised the question of the positioning of the HR function in relation to quantification. In particular, it highlighted the important ambiguities of this positioning linked to the variety of quantification effects for the HR function. Indeed, quantification can be used to evaluate HR policies and their effects, which can contribute in part to the legitimization of the HR function and its action within the organization. On the other hand, more recent developments – particularly in terms of algorithms – also create a risk of automation of certain HR activities, which may encourage the HR function to implement actions aimed at limiting the harmful consequences of this automation.

Chapter 5 mobilized the lessons and examples from previous chapters to address the very broad ethical issues involved in the use of HR quantification. There are several kinds of these challenges: protection of personal data, diversity and the fight against discrimination, and finally the opening of the “black box” of quantification. The choice has been made to close this chapter with recommendations for companies, and in particular by formulating five main principles that can guide the design, deployment and use of HR quantification tools: transparency, auditability, loyalty, vigilance/reflexivity and responsibility. In my opinion, these principles should enable ensuring that the ethical issues related to this subject are taken into account.

C.2. Toward an analytical framework for HR quantification

In the introduction, the fact was highlighted that “HR quantification” covers three practices or situations: quantification of individuals, work and HR function activity. Even if these three practices have their own specificities, illustrated in the chapters, I hope I have also highlighted the multidisciplinary challenges they face: link with the myth of objectivity, use by the HR function, appropriation by the different actors and ethical questions. The aim is to now integrate all these elements into an analysis model of HR quantification tools. To do this, I began by considering that these quantification tools are management tools (Chiapello and Gilbert 2013). Indeed, these are objects or devices that the HR function uses in its management activity. Therefore, the theoretical framework proposed by Chiapello and Gilbert (2013) to analyze management tools can be transposed to quantification tools.

This framework suggests analyzing management tools from three angles: functional, structural and procedural. The functional angle refers to the utility of the tool: what is it used for? Thus, a management tool is defined in part by the links it has with the management activity and ultimately with the organization’s performance. This angle therefore raises the question of the effects of the tool, but also the discourse of the various actors, and in particular the management function, on these effects. These can be of several types: forecasting, organization, coordination and control, for example. The structural angle corresponds to the structure of the management tool, i.e. its materiality and its existence as an object. A management tool thus mobilizes a certain number of materials (e.g. a dashboard, a database and software) that partially structure the actors’ practices. In addition, the management tool processes a certain amount of information, which can relate to individuals, things, resources, actions and results. Finally, the procedural angle refers to the way in which the tool is used by the different actors. Thus, this angle focuses on the variations in the appropriation of the tool by the people who use it, and the possible gap between the use planned by the designers of the tool and the actual use.

Based on the elements of the previous chapters, provided here are examples and information for each of these angles with regard to the different HR quantification tools (Table C.1): statisticalization of individuals and work, reporting and analysis, Big Data and algorithms. In the following, we provide details on the table and specify to which chapters of the book these elements refer.

Thus, with regard to the functional dimension, i.e. the objectives assigned to the tools, the first tool, which is the basis of the other two and which involves the statisticalization of reality, is characterized by a great diversity of purposes (Chapter 1): to plan (in the case of aptitude tests, for example), to organize (work measurement in the context of Taylorism), to manage work (individual evaluation) and to legitimize the action of the HR function by measuring effects. This variety of objectives is explained by the fact that the statistical representation of reality is the essential prelude to the other two quantification tools (reporting/analytics and algorithms). Reporting and analytics focus initially on measurement (Chapter 1): measuring phenomena, the implementation of HR policies and their effects. However, this immediate objective must not obscure more indirect goals (Chapters 2 and 4): that of informing decision making and basing it on quantified elements (what has been named the EBM approach), but also that of legitimizing the action of the HR function by measuring the effects of its actions and establishing quantified links between these effects and the organization’s performance (rhetoric of the business case). Finally, Big Data and the use of HR algorithms are characterized by a predictive and personalized approach (prediction of resignations, personalized training suggestions), but also by new possibilities of work organization by algorithms, as in the case of platforms such as Uber (Chapters 1–3).

Table C.1. The functional, structural and procedural dimensions of quantification tools (theoretical framework borrowed from Chiapello and Gilbert (2013))

| Functional dimension | Structural dimension | Processing dimension | |

| Statisticalization of reality | Measuring reality Forecasting future performance (e.g. aptitude tests) Organizing and coordinating work (e.g. Taylorism) Managing work (e.g. individual evaluation) Legitimizing the action of the HR function (e.g. measuring effects) | Types of mobilized data: Structured data on individuals or work (e.g. measuring the time spent on each task) Types of data produced: Individual indicators (e.g. score on an aptitude test) or aggregated (e.g. job classification) | Use by management and HR: Myth of statistics and data as neutral representations of reality Employee vision: Mistrust, refusal to provide data (e.g. data on an internal social network) |

| Reporting and analytics | Measuring a phenomenon and evaluations (e.g. F/H inequalities) Measuring the implementation of an HR policy (e.g. monitoring | Types of mobilized data: Structured data on individuals or work (e.g. individual characteristics, absenteeism) | Use by management and HR: Myth of objectivity, rationalization (e.g. NPM) |

| indicators) Measuring the performance of the HR function (e.g. indicators of results) Shedding light on decision making (e.g. the EBM approach) Legitimizing the HR function (e.g. business case) | Types of data produced: Aggregated indicators, results of calculations (e.g. averages, medians, effects “all things being equal”) | Vision of employee representatives: Myth of objectivity, but also discussion of interpretations | |

| Big Data, algorithms | Predicting individual behaviors or HR risks (e.g. prediction of resignations) Personalizing services (e.g. personalized training suggestions) Organizing work (e.g. management by algorithms) | Types of mobilized data: Structured or unstructured data on individuals or work Types of data produced: Individual information (e.g. prediction of a candidate’s future performance) or collectives (e.g. analysis of social climate using an internal social network) | Use by management and HR: Rationalization (e.g. algorithmic management) Risk of the HR function being automated (e.g. CV sorting algorithms) Employee vision: Mistrust with regard to disembodied decision making |

The structural dimension applied to HR quantification refers to the data used and produced by these tools (Chapter 1). Thus, the statisticalization of reality, as well as reporting and analytics mobilizes structured data, generally individually, on work and activity. On the other hand, while the statisticalization of reality can produce both individual (aptitude test results) and aggregate indicators (job classification), reporting and analytics most often produce aggregate indicators (averages and average effects). Algorithms and Big Data can accept unstructured data as input, which is not the case for reporting and analytics. In addition, they produce information at an individual level (prediction of the risk of resignation, personalized suggestions for training or positions, or even the allocation of routes to Uber drivers) or at a collective level (analysis of the social climate through comments on an internal social network).

Finally, the procedural dimension transposed to HR quantification can refer to the appropriation of these tools by the different actors (Chapters 2 and 3). Thus, while the HR function and management may see quantification as a tool for objective decision making, but also for managerial rationalization, employees and their representatives may demonstrate certain mistrust. This mistrust may in particular result in the refusal to provide personal data and can be explained by, among other things, the form of disincarnation or disempowerment of the decision that the extensive use of quantification can generate. In the case of reporting and analytics, employees have relatively little access to the figures produced, which are generally reserved for dialogue with employee representatives. However, as we have seen, these representatives can both adhere to the myth of objective quantification, while retaining certain autonomy in interpreting the figures. Finally, the case of Big Data and algorithms raises another challenge for the HR function, linked to the risks of automating certain HR activities.

This table therefore enables integrating many of the elements outlined in the previous chapters. However, it does not cover the elements presented in the last chapter, which are related to ethical issues. Moreover, by applying to HR quantification a framework that refers more generally to management tools, it tends to overwhelm the specificities of HR quantification.

The proposal therefore is to complete this table with a diagram that includes the different dimensions, adding the ethical angle (Chapter 5) but also the specificities of quantification compared to other management tools (Figure C.2).

Figure C.2. Theoretical framework for analyzing HR quantification

The diagram begins by repeating Table C.1 and the three dimensions of the analytical framework for management tools proposed by Chiapello and Gilbert (2013). However, it includes an ethical dimension (Chapter 5): protection of personal data, anti-discrimination and diversity policies, and opacity of tools. The combination of these four dimensions then allows me to identify four main specificities of HR quantification compared to other management tools.

The first specificity – highlighted in particular in the introduction to the book, but which reappears as a common thread in the various chapters – refers to the fact that HR quantification concerns the human being which presents particular challenges, particularly methodological and ethical. The second specificity, largely highlighted in Chapter 2, refers to the myth of objective quantification. This myth, although challenged by many studies, is particularly tenacious, notably in the field of HR, which can be explained by the fact that the HR function needs to be able to legitimize its decisions, actions and policies. The third specificity – to which Chapter 5 goes into detail – corresponds to the highly technical nature of quantification, which requires specific knowledge and skills. This technicality can create a form of opacity for users of quantification tools, particularly HR actors and employee representatives, as well as for those affected by these tools, particularly employees. This specificity introduces challenges of popularization and training of actors. Finally, the fourth specificity is linked to the abundance of actors around the HR quantification chain, from designers to users. This abundance can lead to a dilution of responsibilities, as Chapter 5 has shown. It therefore introduces the need to redefine human responsibilities.

At the end of this process, the hope is to have drawn up a sufficiently broad, if not exhaustive, overview of the uses of HR quantification and the many questions they raise. The desire is to conclude by proposing some ideas for reflection.

The first is the notion of responsibility. Indeed, in Chapter 5 the risks of dilution of responsibility was highlighted and in Chapter 3 the importance of maintaining a form of embodiment of decision making. However, it now seems difficult to define precisely the scope of each actor’s responsibility and to establish rules to avoid the implementation of quantification tools that would make them totally irresponsible. A thorough reflection on the subject could help both organizations and the HR function to define these frameworks.

The second concerns the question of the skills of the HR function but also of employees, employee representatives and designers of quantification tools. Indeed, in Chapter 5 the need was mentioned for each actor to develop their skills. However, it is of course still illusory to imagine that each actor would be an expert in both data analysis and HR issues. This raises the question of the skills really needed for each category of actors in order to ensure that all the issues are properly taken into account.

The third concerns the differences in national legal contexts on issues related to discrimination but also to the protection of personal data. Indeed, there are now major differences on the subject, for example between the United States and the European Union. These disparities can then lead to significant variations in the type of quantification tools produced and implemented within organizations. Proposing a truly international framework on these two subjects – even if it remains at this stage a utopia in view of the many difficulties it would represent – could constitute a major challenge in the coming decades, particularly because of the increasing internationalization of organizations.

The fourth is that the increasing use of quantification creates interfaces between the HR function and other corporate functions, or even society more generally. Thus, quantification gives the HR function new contacts within the company: information systems, IT, statistics, etc. It also requires the HR function to establish partnerships with external actors, for example concerning data storage or the proposal of new services for employees. Finally, it creates new regulatory obligations for the HR function, particularly in relation to the protection of personal data and ethics.

Finally, the fifth concerns the variations that could be observed within the HR function, between the different departments or major HR processes. This question was avoided by mentioning the HR function as a whole or each department concerned if necessary, but without going into the potential systematic differences between departments. Thus, major processes (recruitment, career management or training) have unequal opportunities to use quantification, particularly because they do not have the same amount of data. However, if quantification becomes a source of legitimacy within the company, it could mean that the HR departments or processes least likely to mobilize quantification tools could lose legitimacy to departments or processes that are richer in data and in opportunities to use these data. This question, therefore, requires further research and development.