SECTION 4

THE STRATEGIC CONTEXT OF PROJECTS

,

4.1 Selling Project Management to Senior Managers

4.3 Project Strategic Issue Management

4.4 Project Stakeholder Management

4.5 The Strategic Management of Teams

4.6 Senior Management and Projects

4.7 The Board of Directors and Major Projects

4.9 Portfolio Management for Projects

4.10 Managing Multiple Projects

4.1 SELLING PROJECT MANAGEMENT TO SENIOR MANAGERS

4.1.1 Introduction

Selling project management to senior leaders requires that they recognize a problem and the need for project management as the best solution. The problem that senior leaders have is managing from a strategic point of view and getting the tactical work to align with those high-level goals. Project management, although mature with more than 50 years of formal recognition and growth as a process and discipline, is still developing.

Bridging the problem from a high-level view to the execution of work may be difficult with the need to have a strategic focus by senior leaders. Implementation of the goals in detail is often not understood by the senior leaders and left to the mid- to lower-level leaders. There is not the ability to cascade the thinking from top to bottom.

Senior managers set the tone for the use of project management in the organization. |

4.1.2 Background on Strategic Planning

Senior leaders have the nondelegatable responsibility to establish the principles of work and practices for the organization to follow to achieve success for their business. It is important for senior leaders to establish a system to measure the effectiveness of the strategic planning, through the business process, to the operating level. Through measurement, senior leaders know what is working and what is not, where successes are most needed and where lower priorities may exist.

Senior leaders are concerned with and conduct strategic planning that is far removed from the operating level. Strategic planning, however, uses the historical, tactical information from these operating level systems. Information flow is piecemeal and inadequate for setting the strategic direction and future of the organizations.

Currently, senior leaders seek solutions through improved communication of information and tools to measure performance. What is needed is a management strategy that uses operating units to perform the work and measure performance, analyze the effectiveness of the work being performed, and generate information for senior leaders. Project management does all this and is the choice of many senior leaders today for intensively managing critical aspects of the business.

4.1.3 Recognizing the Problem

Before senior leaders accept any solution, they must recognize the problem and be willing to act on that problem. The problem is clearly identified: “more than 90 percent of organizations fail to effectively communicate and execute their strategic plans because the necessary management and communications systems are not in place.” Organization success is hinged on three requirements:

• Having a management system that emphasizes accountability and control

• Taking advantage of available resources

• Promoting cultural values dedicated to continual improvement that is supported by an appropriate management system

Current management systems are not delivering the desired results and the communication of strategic goals from senior leaders to operating levels is weak. The layers of management between the senior leaders and operating levels preclude effective information flow down and the required performance flow back to the top.

One perceived solution to the communication breakdown is to buy new information management tools. Better information systems are seen as the need while the efficiency and effectiveness of the operating unit has not changed. More timely and accurate reporting of the performance data is only one part of the challenge to senior leaders.

The management system and operating units retain the same structure and there is little or no improvement in productivity or meeting customer needs.

4.1.4 The Solution

Senior management is responsible for its management systems locally and globally. These management systems should be mutually supportive of the strategic goals as well as taking advantages of improvements across the enterprise. The management system of choice must be supportive of both local and global environments.

Many organizations have adopted project management as the system of choice and made significant gains in productivity and performance. Other organizations have accepted project management as one of its options without giving full support. These organizations have “hired” expertise through bringing in several successful project managers from other organizations. The hired experts bring a variety of methodologies and practices that create conflicts.

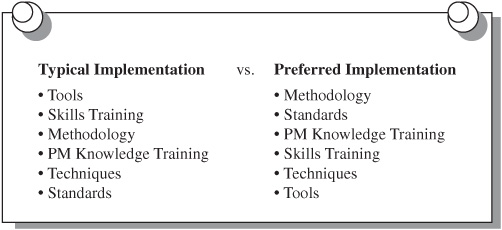

Developing project management as a core competence of an organization is a dedicated effort. Typically, organizations buy tools rather than knowledge and experience. Many organizations do not receive full value because they buy tools. Figure 4.1 compares the most frequent and the most effective sequence of project management implementation.

FIGURE 4.1 Project management implementation sequence.

4.1.5 Benefits of Project Management

Project management, as a process to meet an organization’s needs for performing a variety of work, has provided significant benefits. The general list of benefits for all organizations is as follows:

• Balance competing demands and prioritize the work that provides the most advantage to the organization

• Positive control over work progress through a tracking and control function

• Positive communication of needs to project team and frequent feedback to the customer on progress

• Estimates of future resource needs through the life cycle of the project

• Early identification of problems, issues, and risks to project work

• Early understanding of scope of work

• Goals and measures of success for each project

• An integral performance measurement capability to compare planned to actual progress

4.1.6 Comparison of Operations to Project Management

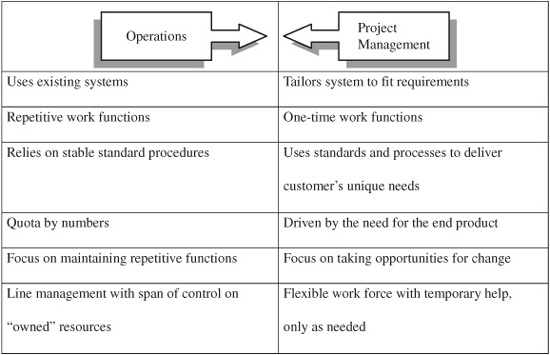

A comparison of operations to project management capabilities, as depicted in Fig. 4.2 is helpful to identify the advantages of project management under different conditions. Operations typically focus on maintaining the status quo and producing a given set of products. Project management, however, serves as a process for change and delivering unique products.

FIGURE 4.2 Operations versus project management.

4.1.7 Selling Project Management

Selling project management as the management system of choice requires that the seller provide facts and figures to demonstrate the advantages. The advantages must give a better solution than the current system and demonstrate significant benefits to senior leaders. There must be a perceived problem to be solved and all elements of that problem must be solved.

The simple model for selling project management is:

• Identify senior leaders’ problem with the organization.

• Low productivity.

• Uncontrolled work being done.

• Insufficient accurate information on progress.

• Work doesn’t follow strategic direction.

• Work doesn’t take advantage of product changes.

• Identify causes of senior leaders’ complaint.

• Workforce not keeping pace with technological advances.

• Poor definition of work and poor control over work.

• Weak or no communication system.

• Work driven by perceived requirements based on historical information rather than the strategic direction.

• System too rigid to accommodate product changes except on a planned changeover.

Develop a comparison of current operations, feasible fixes to current operations, and a project management driven approach. See the following illustration and example in Fig. 4.3.

The differences can be documented using a similar model that captures the current problems with the operations, identifies the changes within the current management system to correct weaknesses, and identifies the benefits of transitioning to a project management system. While senior leaders can be influenced by cost figures, there are few data collected that truly represent the situation.

Soft data are often required to justify a transition to project management. Some of these soft data areas are:

• Reduced time to market for products

• Improved information reporting

• Better visibility into the product-build process

FIGURE 4.3 Comparison of operations to project management.

• Reduced human resource stress

• Rapid response to product changes

• Continuous improvement opportunities

• Improved productivity (qualitative)

• Improved return on investment (qualitative)

• Alignment of tactical work with strategic goals

Other areas may be applicable within different industries. Reduced risk through improved risk management procedures, for example, may be an area that is important. Improve product image through improved customer communications could be another area.

4.1.8 Summary

A project management system will consistently outperform standard operations functions and provide better results. The dynamic business environment where “more than 90 percent of the organizations fail to effectively communicate and execute their strategic plans” provides many opportunities to sell project management as the management system of choice. Organizations need the discipline of project management while receiving the benefits of a flexible, tailored workforce to complete work.

Selling project management to senior leaders requires a comparison of the benefits and risks to be developed for each organization. These benefits over current operations will provide the reason for change. Project management must be sold as the solution to existing weaknesses and it must be demonstrated as to how these will be overcome.

4.2 PROJECT PARTNERING

4.2.1 Introduction

Partnering in projects has emerged in recent years as a means of sharing equally in managing large projects by two or more organizations. One organization may initiate partnering to gain additional capability for a project as well as share in the risks of large, complex projects. Partnering is also a means of combining information, such as in research and development projects, to improve the chance of success.

Partnering may be accomplished between public, private, and for-profit and not-for-profit organizations. A government agency may, for example, partner with a private organization to conduct research. Another example is for a private, for-profit professional association to partner with a not-for-profit company to develop a commercial product from intellectual property.

There is no limit to project partnering by organizations. A common goal and complementing capabilities are the basis for a project partnership. Finding the talent needed to perform specific project work and developing cooperative arrangements for the partnering are needed for a working partnership.

A partnership is an affiliation of parties who seek a common purpose. |

4.2.2 Types of Project Partnering Arrangements

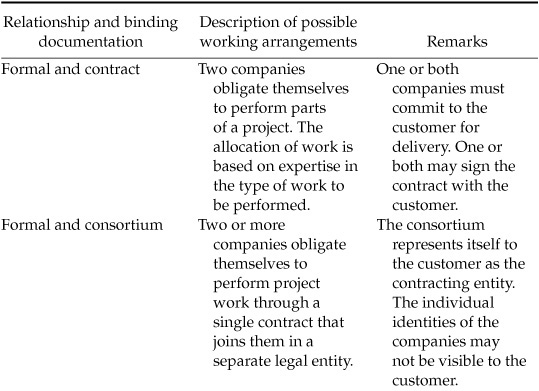

Project partnerships may take many forms of cooperative agreements. The formality and contractual relationship is determined by the needs of all partners. Some examples of these relationships are depicted in Table 4.1.

TABLE 4.1 Types of Project Partnering Arrangements

The number of arrangements is left to the organizations desiring to partner and work together. One important aspect is the visibility that the customer has of the accomplishment of different work packages. In some partnering, the customer wants to be aware of who is doing the work and in other situations, the customer is only concerned with quality of the work.

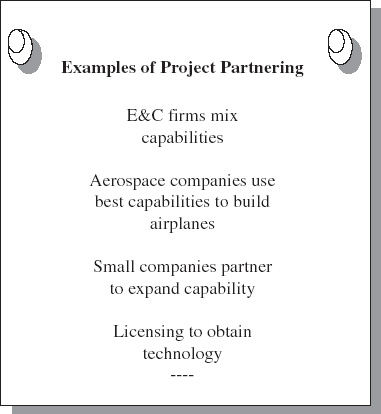

4.2.3 Examples of Project Partnering

There are many examples of project partnering that demonstrate the concept and the future of this type of business relationship. Figure 4.4 shows several examples of project partnering.

• Engineering and construction firms partner to obtain the best mix of talent and capability for projects. Partnering to obtain excellence in project control for major projects is often found in major projects such as the Super Collider Project in Dallas, Texas.

• Aerospace companies partnered to build a stealth bomber on a $4 billion project. Several companies worked together to develop the best in stealth technology. Technology was the driving force for partnering. The combination of companies could not solve the technical problems and the project was cancelled when the cost was estimated to exceed nearly $7 billion.

FIGURE 4.4 Examples of project partnering.

• Three small companies combined their capabilities to bid and win a project requiring expertise in computer technology, computer network operations, and procurement knowledge. The project, although relatively small, combined the talents from all three companies to perform the required tasks.

• Licensing of intellectual property of a professional association to a company to build software products is a current project. The association’s standards were licensed to a company for the specific purpose of expanding the distribution of knowledge in the standards and to generate a modest profit for the association. This is partnering in that the professional association retains review over the products developed by the company.

4.2.4 Managing Partnered Projects

Customers are concerned with the management of the project work and who will be responsible for such items as reports, corrective actions, changes to the project, and overall project direction. Strong management capability builds confidence with the customer, while a weak or vague project management structure erodes confidence.

Figure 4.5 shows typical types of arrangements for managing partnered projects. A detailed discussion follows. Some management structures for partnered projects are:

• Steering committee—senior managers from all partnering organizations. This committee reviews progress and sets direction. A project manager or co-project managers are designated for all partnered work and report to the steering committee.

FIGURE 4.5 Managing partnered projects.

• Project manager and deputy project manager (or co-project manager)—two individuals are designated from the partnering companies to lead the project. These individuals may report to their respective company executives or to a steering committee.

• Project manager—a single individual is appointed as the project manager for all the project work. Project team members report to the project manager for performance issues.

These three management structures can be modified to meet any situation. Large projects need senior guidance from a group such as a steering committee, while small projects would only require a single project manager. The management structure must meet the needs of both the project and the customer.

4.2.5 Technical Aspects of Partnered Projects

One of the primary reasons for partnering is to gain additional technical capability. A customer wants assurances that the project will be technically successful and that the performing organization has the capability to accomplish the work. Partnering gives that assurance by bringing the best talent from more than one company.

Principles of partnering will guide companies to better work solutions and better products for the customers. The following is a list of principles:

• Work allocation. Divide work so the work packages are performed with an integral team where possible. Attempting to develop teams on a short-term basis may not be the most efficient use of talent and expertise. So, a team from one of the partnering companies should be assigned work packages commensurate with its skill.

• Project control. A team should be assigned responsibility for controlling the project work. This team may be individuals from different organizations, but it should have specific work responsibilities. The project control team must report to the project manager.

• Project management. There needs to be a single person responsible for managing the work. Some work may be performed under the supervision of a manager, but that manager is responsible to the project manager for delivering a product component. All elements of the project must be managed from a single person with the authority to direct and accept work.

• Company participation. Company managers must not, as individuals, become involved in the direction of the project. Direction must be through a consolidate body, such as a steering committee or senior management representative group. Individuals may bring the wrong solutions to the partnered project.

• Customer interface. Like any project, partnered projects must have a single interface with the customer. This may be the project manager, the chair of the steering committee, or the elected representative from the management group. In some situations, there are two levels of customer interface. The strategic direction and liaison is from the senior steering committee and the daily interface is between the project manager and the customer’s representative.

4.2.6 Benefits in Partnered Projects

Partnering has benefits that exceed those that a single organization may derive from a project. The benefits can be short-term or long-term, with a major impact on future business. Some of the benefits for the partnering organizations are:

• Technology. Partnering with a high-technology exposes personnel to state of the art technology and processes. These technologies may be used in future projects or they may serve as information when seeking future partnering relationships.

• Small to large companies. Small companies partnering with large companies learn improved methods of managing and bidding on projects. The transfer of knowledge is valuable to small companies in future work.

• Managing projects. All partnering organizations gain skills and knowledge on how to better manage projects. The cross-pollination of skill, knowledge, and abilities helps organizations improve the project management capabilities.

• Efficiency. Availability of a large resource pool should give the right skills for the work and lead to a more efficient level of work. This efficiency should yield benefits in that rework and other waste could be significantly reduced.

• Monetary rewards. Improvements in management and work processes from a wide base of several companies should result in improved profits. The efficiency and effectiveness of the work will cost less to perform and yield a better margin.

• Corporate image. If companies in partnered projects are visible, the efficiency and effectiveness may improve the image as quality performing organizations. This image and reputation can be used in future bidding and project work, whether partnering or alone on a project.

4.2.7 Summary

Project partnering takes on many forms based on the desires and creativity of the partners. The arrangements will vary according to the project and the visibility of organizations may be more or less, depending upon the needs for the partnered project. Organizations, public and private, for-profit and not-for-profit, can create partnerships to meet the needs of a small, medium, or large project.

Managing a partnered project is typically driven by the desires of the customer. Customer confidence and visibility into the project dictate the management structure as well as the size of the project. It is not uncommon to have a two tier management structure, a project manager and a steering committee to which the project manager reports.

4.3 PROJECT STRATEGIC ISSUE MANAGEMENT

4.3.1 Introduction

In a project, a strategic issue is a condition or pressure, either internal or external, which has the potential for a significant influence on one or more factors of a project during its life cycle, such as its cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives as well as financing, design, engineering, construction, and operation. Strategic issues can arise from many different stakeholder groups: customers, suppliers, the public, government, intervenors, and so forth. Some examples of strategic issues include:

• The need to reduce time required to design, develop, and produce an automobile—resolved through the practice of concurrent engineering

• The failure to recognize the environmental-related and political issues in product development, which, in the case of the U.S. Supersonic Transport Program led to the cancellation of that program by the U.S. Congress

• The need to develop strategies for a “turn-around” project underway at Eastman Kodak—remedial action was required to reduce and eliminate resistance to change from the employees

• The emergence of a key environmental-related factor which held potential to delay or cancel a project, as in the case of the discovery of an earthquake fault offshore from the construction site of a nuclear generating plant

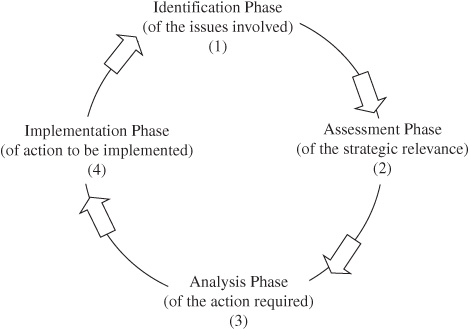

FIGURE 4.6 Key phases for managing strategic issues for a project. (Source: Adapted from David I. Cleland and Lewis R. Ireland, Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation, 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 2007, p. 172.)

A strategic issue is a point of contention involving a project. |

4.3.2 Managing Project Strategic Issues

There are four key phases involved in the management of strategic issues for a project. These phases are portrayed in Fig. 4.6, and discussed below.

4.3.2.1 Identification Phase. Chances for the identification of potential issues facing the project can be enhanced if in the project planning a “work package” is established for the identification and management of the strategic issues. At each review of project progress, consideration should be given to whether or not any strategic issues have arisen that could impact the project. By reviewing the project stakeholder interests in the project, the likelihood of strategic issues coming forth is enhanced.

4.3.2.2 Assessment Phase. In this phase, judging an issue’s importance is essential. Several criteria can be used to assess the importance of an issue, such as:

• Strategic relevance, or magnitude and duration of the issue.

• Actionability considers whether or not the project team has the knowledge and resources to deal with the issue. A project may face an issue over which it has little control. In such issues, keeping track of the issue and considering its potential impact may be the only realistic strategy that can be pursued. For example, in government defense work, contracts can be cancelled at the convenience of the government.

• Criticality of an issue relates to the importance of the potential impact of the issue on the project. If an issue appears to be noncritical, then continued monitoring of the issue may be all that is needed.

• Urgency of the issue regarding the time period in which something needs to be done.

4.3.2.3 Analysis of Action. In the analysis of strategies and actions required to deal with the project, seeking answers to the following types of questions can be useful:

• What will be the probable effect of the issue in terms of impacting the project’s cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives?

• What might be the impact on the project of the key stakeholders involved in the issue?

• What specific strategies have to be developed by the project team to deal with the issue(s)?

• What resources will need to be committed to deal with the issue?

4.3.2.4 Implementation of Action. In this phase, a plan of action is implemented. The action plan and its implementation can be dealt with as a subproject and involves all of the elements in the management of a project, such as planning, organizing, direction, control, and so forth. An important part of the implementation phase is a review of the strategic issues during the regular review of the project’s progress.

4.3.3 Summary

A strategic issue in a project is a condition or pressure that has the potential to have a significant impact on the project. Strategic issues can arise from within the organization, and from outside, such as major concerns or forces that the project stakeholders consider of importance to the project. In this section a few ideas were presented on how a project team could better manage the strategic issues that their project faces. Strategic issues can arise at any stage in the life cycle of the project. The project manager should be aware of the concept of project strategic issues, and provide proactive leadership in dealing with the strategic issues that are likely to impact the project.

4.4 PROJECT STAKEHOLDER MANAGEMENT

4.4.1 Introduction

Project stakeholders are those individuals, organizations, institutions, agencies, and other organizations that have, or believe that they have a claim or stake in the project and its outcome. Stakeholders in the political, economic, social, legal, technological, and competitive environments have the potential to impact a project. Project managers need to identify and manage those stakeholders likely to have an influence on the project’s outcome.

A stakeholder is a party who has a claim regarding a project. |

4.4.2 Examples of Stakeholder Influence

• Actions by environmental groups that delayed progress on the design and construction of nuclear power-generating plants in the United States.

• On the James Bay Project in Canada, special effort was made to stay sensitive to social, economic, and ecological issues coming from vested stakeholder interests on that project.

• Proactive action by environmentalists, tourists, and government agencies motivated the project team to take special care to protect and preserve the scenic well-being of an area during the construction of a highway through Glenwood Canyon in Colorado.

• Stakeholder action caused the rerouting of a major highway in Pittsburgh, PA, to preclude the razing of an old church that had historical value to the community.

• Failure on the part of the project team to manage the political interests of key U.S. congressmen and environmental groups who developed such organized opposition to the U.S. Supersonic Transport Program that it was cancelled by lawmakers, even though the technological feasibility of the aircraft had been demonstrated.

4.4.3 Evaluating Potential Stakeholder Influence

Developing a strategy to consider the potential impact of project stakeholders can start with seeking the answers to a few key questions such as:

• Who are the project stakeholders, both primary and secondary?

• What stake, right, or claim do they have in the project?

• What opportunities and challenges do the stakeholders pose for the project team?

• What obligations or responsibilities does the project team have toward its stakeholders?

• What are the strengths, weaknesses, and probable strategies that the stakeholders might use to realize their objectives?

• What resources are available to the stakeholders to implement their strategies?

• Do any of these factors give the stakeholders a distinctly favorable position in affecting the project outcome?

• What strategies should the project team develop and use to deal with the opportunities and challenges presented by the stakeholders?

• How will the project team know if it is successfully managing the project stakeholders?

4.4.4 A Model of the Project Stakeholder Management Process

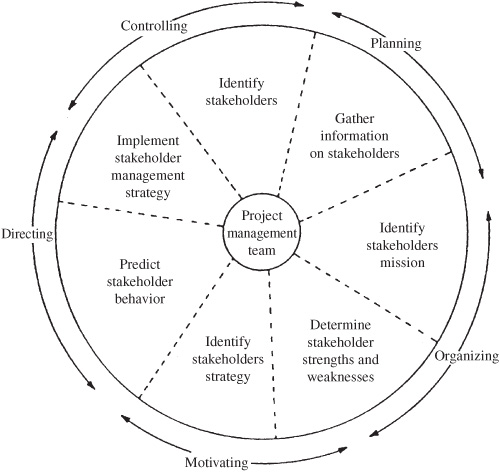

The process of dealing with stakeholders focuses around the application of the management functions (planning, organizing, motivating, directing, and controlling) to potential stakeholder issues. Figure 4.7 shows a model of such process.

4.4.4.1 Identification of Stakeholders. A project usually faces two kinds of stakeholders: (1) primary stakeholders who have a contractual or legal obligation to the project team; and (2) secondary stakeholders who usually have no formal contractual relationship to the project team but have, or believe that they have, a stake in the project or its outcome. Figure 4.8 is a model of these stakeholders.

The key authority and responsibility of the primary stakeholders include:

• Providing leadership to the project team

• Allocating resources for use in the design, development, and construction (production) of the project results

• Building and maintaining relationships with all stakeholders

• Managing the decision context in the design and execution of strategies to commit project resources

• By example, set the project’s cultural ambience, which emphasizes the best of people in providing high-quality professional resources to the good of the project

FIGURE 4.7 Project stakeholder management process. (Source: David I. Cleland and Lewis R. Ireland, Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation, 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 2002, p. 151.)

• Maintain ongoing and effective oversight of the project’s progress in meeting the schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives, and where necessary reallocating and reprogramming resources as needed to keep the project on track

• Periodically checking the efficiency and effectiveness of the project team in doing the job for which they were hired

Secondary stakeholders can be difficult to manage. Some of the more obvious characteristics of these stakeholders include:

• There are no limits to where they can go and with whom they can talk to influence the project.

• Their interests may be real or perceived to be real as the project and its results may infringe on their “territory.”

• Their “membership” on the project team is ad hoc—they stay so long as it makes sense to them in gaining some advantage or objectives involving the project.

FIGURE 4.8 The project stakeholders. (Source: Cleland, David I., “Stakeholder Management,” Chap. 4 in Jeffrey K. Pinto (ed.), Project Management Handbook, Project Management Institute, Newtown Square and Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1998, p. 61.)

• They may team up with other stakeholders temporarily to pursue their common interest for or against the project’s purposes.

• The power they exercise takes many forms such as political influence, legal actions, such as court injunctions, emotional appeal, media support, social pressure, local community action, and even scare tactics.

• They have a choice of whether or not to accept responsibility for their strategies and actions.

4.4.4.2 Gathering Information of Stakeholders. Information about project stakeholders can come from a wide variety of sources to include:

• Project team members

• Key managers

• Business periodicals including The Wall Street Journal, Fortune, Business Week, and Forbes

• Business reference services, including Moody’s Industrial Manual, Value Line Investment and Security

• Professional associations

• Customers and users

• Suppliers

• Trade associations

• Local and trade press

• Annual corporate reports

• Articles and papers presented at professional meetings

• Public meetings

• Government sources

• Internet

4.4.4.3 Identifying Stakeholder Mission. This involves a determination of the mission of the stakeholders that support their vested interests in the project. For example, the mission of a stakeholder group on a highway project in Pittsburgh, PA, was to “change the route of the freeway highway to avoid razing of the historical church.”

Stakeholders can be supportive or adversarial—with degrees of influence in between. Both types require managing—to strengthen the project by gaining continued support or to reduce as much as possible the likely adversarial impact of the stakeholders on the project.

4.4.4.4 Determining Stakeholders’ Strengths and Weaknesses. The determination of the stakeholders’ strengths and weaknesses is essential to ascertaining how successful they might be in influencing either the project or its outcome. A stakeholder’s strengths might include those listed in Table 4.2.

Conversely, the weaknesses of a particular stakeholder group might include those listed in Table 4.3.

4.4.4.5 Identification of Stakeholder Strategy. A stakeholder strategy is a prescription of the collective means by which resources are dedicated for the purpose of accomplishing the stakeholder’s mission, objectives, and goals. These prescriptions stipulate what resources are available, and how such resources will be used in an organized fashion to accomplish the stakeholder’s purposes. The use of legal means to stop construction on a project because of claims of adverse impact on the ecology is one principal strategy used by stakeholders. Another means is to seek support from political bodies to influence the project. Picketing construction sites, letter writing campaigns, paid radio or TV advertisements are other means that stakeholders can use. Once an understanding of the stakeholder’s strategy is gained, then the chances are increased to predict what the stakeholders’ behavior will be.

TABLE 4.2 Stakeholders’ Strengths

• Availability and use of resources |

• Political and public support |

• Quality of their strategies |

• Dedication of the stakeholder members |

TABLE 4.3 Stakeholders’ Weaknesses

• Lack of public and political support |

• Lack of organizational effectiveness |

• Inadequate strategies |

• Uncommitted, scattered members |

• Poor use of resources |

• General incompetence |

4.4.4.6 Predicting Stakeholder’s Behavior. How will the stakeholders use their resources to affect the project? This is the key question to be answered. There are many alternatives available to the stakeholders to attain their end purposes. These can include:

• Influencing the economic outcome of the project—as a construction union might do when a new manufacturing plant is being built

• Attaining specific objectives of the stakeholder—such as the protection of the environment, which is part of the mission of the Sierra Club

• Legal actions to influence the outcome of the project—such as work stoppage orders until stakeholder claims of safety are resolved

• Political actions through gaining the support of legislators—such as having governmental projects funded for construction in their political districts

• Health and safety—often brought up when new drugs or medical protocols are being developed

4.4.4.7 Implementing Stakeholder Management Strategy. The final step depicted in Fig. 4.7 in managing the project stakeholders is to develop protocol for the implementation of the resources dedicated to managing the stakeholders. Once the implementation phase has been embarked on, the project team needs to:

• Be sure that the key managers and professionals appreciate the impact that both supportive and nonsupportive stakeholders may have on the project outcome.

• Manage the project review meetings so that the stakeholder assessment is an essential part of deciding the project status.

• Keep in touch with key external stakeholders to improve the chances of determining stakeholders’ understanding of the project and its strategies.

• Ensure a clear evaluation of possible stakeholder response to major project decisions.

• Provide ongoing, current reports on stakeholder status to key managers and professionals for use in developing and implementing project strategy.

• Provide a proper security system to protect sensitive project information that might be used by adverse stakeholders to impact the project’s success.

4.4.5 Summary

The management of project stakeholders is a vital “work package” in planning for and implementing the use of resources on the project. An individual should be assigned a specific “work package” responsibility on the project team to identify, track, and manage the project during its life cycle.

4.5 THE STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT OF TEAMS

4.5.1 Introduction

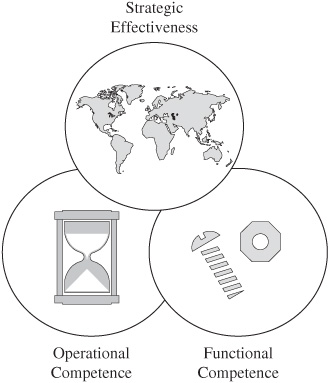

The essence of managing an organization from a strategic perspective is to maintain a balance in using resources to accomplish organizational mission, objectives, and goals. The key is to balance operational competence, strategic effectiveness, and functional excellence. Figure 4.9 shows the linkage between strategic effectiveness, operational competence, and functional excellence for teams. These terms are defined below:

Operational competence is the ability to use resources to provide customers with high-quality products and services so that sufficient profit is realized to advance the state-of-the-art in such products and services, and have sufficient funds left over to develop new strategic initiatives for the organization.

FIGURE 4.9 Balance between strategic management challenges. (Source: David I. Cleland, Strategic Management of Teams, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1996, p. 5.)

Strategic effectiveness is the ability to assess the need for, and develop future products, services, and organizational processes. Alternative project teams, as described in Sec. 3 can be used to assess the possibilities and probabilities in the use of resources to ensure the organization’s future.

Functional competence is the ability to maintain state-of-the-art ability in the use of resources to support the organization’s current and future needs.

A balance must be maintained among the organization’s operational competence, its strategic effectiveness, and its functional excellence, as depicted in Fig. 4.9. This balance can be facilitated by providing appropriate project team linkages within the organization.

Project teams can make a difference in the strategic management of an organization. |

4.5.2 The Team Linkages

There are many team-driven organizational initiatives that are endemic to the strategic management of the organization. Some of these initiatives are discussed below:

• Reengineering teams used to bring about a fundamental rethinking and radical redesign of business processes. The output of these teams is improved business and processed changes in the organization.

• Crisis management teams that serve as a focus for any crises that might arise in the organization’s activities.

• Product/process development teams which provide for the concurrent design and development of products, services, and organizational processes. Effective use of such teams results in higher quality products, services, and organizational processes, developed at a lower cost and leading to earlier commercialization and greater profitability.

• Self-directed production teams which manage themselves and when team members are adequately prepared and used can result in greater efficiency and effectiveness in the manufacturing or production activity of the organization.

• Task forces which are ad hoc groups to solve short-term organizational problems or exploit opportunities to support the operational and strategic well-being of the organization.

• Benchmarking teams used to measure the organization against the most formidable competitors and industry leaders. When properly used the results of the work of these teams can be improved operational and strategic performance.

• Facilities construction teams design, develop, and construct capital improvements for the organization. This is the “traditional” use of project teams which have reached considerable maturity in industries such as construction, defense, engineering, research, and in government, educational, health systems, and economic development agencies.

The use of alternative project teams has been necessary in part because of the way that jobs and strategies are changing in contemporary times.

4.5.3 Jobs Are Changing

Jobs are changing from fixed specific areas of responsibility to a team effort. The use of part-time and temporary workers is increasing; the organizational design today is undergoing major changes. Some of the more important other job changes include:

• An organizational design is used that is more flexible than the traditional structure based on specialization of work.

• There is increased reliance on alternative teams to deal with the change affecting the organization, particularly in the development of new and improved products and organizational processes.

• There is increasing acceptance of the belief that traditionally structured organizations are inherently designed to maintain the status quo rather than respond to the changing demands of the market and competition.

• There is less reliance on job descriptions or supervisor directions; rather the team members take their direction from the changing demands of the team objectives.

• Workers develop the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to deal with individual effort and the collective responsibility of the team.

• Team members report to each other, look for facilitation and coaching from the team leader, and focus their effort on the resources needed to meet team objectives.

• A single job is important only insofar as it contributes to the bundle of capabilities needed to get the team’s work done.

Along with job changes, the traditional roles of managers and supervisors are changing. In fact, such traditional roles are becoming an endangered species. Team leader members are performing many of the traditional duties of these previous “in-charge” people. Contemporary managers are becoming mentors, facilitators, teachers, coaches, and other roles which are different from the “in-charge” nature of earlier periods. Team leaders and members are performing many of these traditional manager roles such as:

• Planning the work and assignment of the tasks by members of the team

• Evaluating individual and team performance in doing the work

• Moving toward both individual and team rewards

• Counseling poor team performers

• Participating in key decisions involving the work the team is doing

• Organizing the team members regarding their individual and collective roles

• Taking responsibility for the quality of the work, team productivity, and efficiency in the use of resources

• Developing initiatives to improve the quality and quantity of the output

• Seeking better ways of doing the work and, in so doing, discovering creative and innovative means of preparing for the team and the organization’s future

• A form of team building required to prepare the organization for the use of teams

4.5.4 Preparing the Enterprise for the Use of Teams

There are some important fundamentals that managers need to recognize when preparing the enterprise for the use of teams in the organization. These include:

• An ability of the different teams to work with each other and to respect each other’s territory

• Recognition of the high degree of interdependence among the members of the team, and how that interdependence can be used as a strength for integrated team results

• A willingness of the team members to share their information and work with each other, leading to a high degree of collaboration among team members

• Recognition of the deliberate conflict usually found in team work—a conflict, often stemming from different backgrounds, which exists because of substantive issues and not interpersonal strife

• A more efficient way for team members to proactively seek ways to work out problems and opportunities through team members to reach a result in which each member sees part of his or her work in the solution

• A better understanding of the culture of the team, its thought and work processes, and greater willingness to give unselfish support to the team’s objectives and goals

• Enhanced communication among the team members about their individual and collective work on the team

• Better understanding of the purpose of the team, its relationship with the work of other teams, and how everything comes together to support the mission, objectives, and goals of the enterprise

• Greater opportunity for a higher degree of esprit de corps, a sense of belonging on the part of the members, and pride in working together to accomplish desired ends

The responsibilities with which the members of the design and implementation team are charged for the design and implementation of a team-driven strategy in the organization include the following:

• Providing for the transfer of the organization’s vision and values to the teams

• Developing documentation for the teams, including a supporting charter, authority-accountability-responsibility relations, work redesign, and general cultural support

• Providing both conceptual and work linkages between the teams and the other organizational elements

• Evaluating existing reward systems for compatibility with the team organizational design

• Becoming the champion for the transformation of the organization from its traditional configuration to one characterized by team modes, values, and processes

• Providing general support, including allocation of resources

• Evaluating how the teams will interface with the functional expertise, strategic management, and cultural characteristics of the organization

• Recommending training initiatives to support the transition to a team-driven organization

• Assessing the existing supporting technologies, such as computer and information systems, to support the team architecture

4.5.5 Summary

Teams working in cross-functional and cross-organizational environments are making major contributions to the operational and strategic well-being of contemporary organizations. The decision to use teams in the organization’s strategy should be carefully assessed, to include the potential value of such teams, how the enterprise has to be prepared for using teams, and how the oversight of teams will be carried out. Changes in the culture of the organization will be profound when teams are introduced and used as elements of organization’s strategy.

4.6 SENIOR MANAGEMENT AND PROJECTS

4.6.1 Introduction

Senior managers, including general managers, have the residual authority and responsibility for the management of the organization, and are responsible to the Board of Directors (BOD). Since projects are building blocks in the design and execution of strategic management initiatives, these managers should pay particular attention to why projects are used in the organization and how well they are managed.

Senior managers have the residual responsibility and accountability for the management of projects in the organization. |

4.6.2 Senior Management Responsibility for Projects

• Ensuring the adequate organizational design has been established

• Ensuring that the cultural ambience of the organization is evaluated to determine how well such culture will support the use of projects

• Providing resources to update the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of people associated directly with the projects

• Maintaining oversight over the development and acceptance of a plan of action for each project

• Seeing that an adequate information system exists that contributes to the planning and execution of projects

• Ensuring a system for monitoring, evaluating, and controlling the use of resources on projects to include an assessment of how well projects are meeting their cost, schedule, and technical performance goals and objectives

• Maintaining an ongoing consideration of where projects have, and will continue to have, a strategic fit in the organization’s mission

The authority and responsibility of the senior managers of the organization and its directors are similar. If the directors of the enterprise are going to do their job in maintaining oversight over the planning and execution of projects, then the senior managers must ensure that the adequate management systems are in place in the organization, and that the directors are kept informed on the status of major projects underway.

4.6.3 Which Projects?

In an ongoing organization there can be hundreds of projects, of all sizes, and for different purposes in the product, service’ and processes of the enterprise. General guidelines for which projects’ senior managers should be directly concerned will include:

• New product, service, and organizational process projects which have the promise of providing a competitive advantage in the marketplace

• Product/service projects which contain the potential for breakthroughs in technology, significant reduction of development costs, or the promise of bringing the product to earlier commercialization

• Projects that require the commitment and obligation of substantial enterprise resources, which if inappropriately applied can reduce the financial or competitive well-being of the organization

• Projects that are linked to strategic alliances with other organizations such as those designed to share development risks, or penetrate local markets in the global marketplace

• Projects which are closely linked to such strategies as downsizing, restructuring, cost reduction, productivity improvement, investment opportunities, or acquisitions, mergers, and alliances with other organizations

Senior management must develop a means for surveying the major projects underway, and determine which are sufficiently important that their personal involvement in planning for and execution of project strategies is required.

If adequate oversight of the firm’s projects is not carried out, there is a risk of failure of one or more projects. Such failures could impact the competitive advantage that the organization holds in the market place. Some of the more common failures on the part of the oversight of senior managers are shown in what follows.

4.6.4 An Inventory of the Causes of Failures

• A lack of appreciation of how projects are inexorably tied to the operational and strategic trajectories of the organization

• Unwillingness to become involved in assessing how well the projects are being planned and carried out

• Ignorance of how projects should be managed in the spirit of a “systems approach” as outlined elsewhere in this Handbook

• Not providing resources that are needed to support the projects, as well as failing to understand and articulate how the organization’s projects are linked to functional and other organizational units in the organization

• Not requiring that all projects in the organization should be reviewed on a regular basis following the model for monitoring, evaluation, and control suggested in Sec. 7.1 of this Handbook

• Not providing suitable recognition of project efforts

• Not understanding, and thus likely not appreciating, the impact that project stakeholders can have on in-house projects

• Neglecting the commitment of resources to train project teams in the management of projects

• Not being a role model for how prudent and effective management can be carried out in the organization

4.6.5 Senior Management Review by Life Cycle Phases

Conceptual phase is the period when a conceptual framework for the project is being determined to include probable cost, schedule, technical performance objective, and potential strategic fit. Major responsibilities of senior managers include:

• Evaluating potential “deliverables” of the project to include probable strategic fit in the organization’s businesses

• Determining the ability of the organization to provide the resources to support the project during its life cycle

• Determining the capability of the organization to provide trained people to serve on the project team as well as provide human resource support from the functional entities of the organization

• Selecting of the “right” project manager who is clothed with the authority and responsibility to manage the project

• Ascertaining if adequate planning has been established for the project

• Finally, seeing that the project and its deliverables are appropriately linked to the operational and strategic purposes of the organization; require contingency planning for the early termination of the project

Execution phase is the phase when resources are committed to the project and its design, development, and execution is underway. Major responsibilities include:

• Provisioning of resources to support the project

• Giving the project manager and the project team the freedom to manage the project without interference from other managers

• Providing oversight of the project’s cost, schedule, and technical performance progress followed by appropriate feedback to the project manager and project team

• Maintaining contact with key stakeholders such as project customers, suppliers, and regulatory agencies

• Ensuring that other managers in the organization are committed to supporting the project through the allocation of needed resources

• Allowing the project manager and team members enough freedom to follow their muse in finding innovative and creative solutions to problems and opportunities

• Providing a buffer to guard the project against the inevitable politics that come up in any organization and its stakeholders

• Providing suitable rewards and inducements to bring out the best performance in the people supporting the project

• Determining if a project audit review would make sense

Postproject phase is the phase when the project’s results are being integrated into the operational and strategic business of the organization. Major responsibilities during this phase include:

• Ensuring the successful strategic fit of the project into the affairs of the organization

• Ensuring that appropriate measures have been taken for the after-sales support of the project results

• Doing a postproject review to gather information on how well the project was managed to include a collection of “lessons learned” that can be passed on to other project management initiatives

• Examining the rationale for the project to support organizational purposes

4.6.6 Summary

In this section, the role of senior managers in maintaining oversight of the planning for and execution of projects was presented. Such managers have key responsibilities in the planning for projects to include an assessment of what the likely strategic fit of the project will be. The role of these managers was described in the three key phases of a project, with appropriate oversight responsibilities that senior managers should carry out during these phases.

4.7 THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND MAJOR PROJECTS

4.7.1 Introduction

Once a project is funded and organization resources are being used to design, develop, and construct (manufacture) the project, the BOD has an important responsibility to maintain surveillance over the progress that is being made on the project. By maintaining such surveillance, the BOD gains valuable insight into how well the organization is being prepared for its future. The projects over which the BOD and senior management of the organization should maintain approval and oversight include:

• New product, service, and organizational process projects, which hold the promise of giving the organization significant competitive advantage in the marketplace

• Projects which require the commitment of substantial resources such as new facilities, restructuring, reengineering, or downsizing initiatives

• Projects that lead to strategic alliances, research consortia, partnering, and major cooperative efforts with other organizations

• Major initiatives that promise to provide initial or expanded presence in the global marketplace

• Projects, such as concurrent engineering initiatives, which promise to provide earlier commercialization of products and services

• Projects that lead to potential major changes in the organization’s mission, objectives, goals, or strategies

By maintaining oversight over these kinds of projects the BOD members gain valuable insight into how well the organization is preparing itself for the future.

The BOD has principal fiduciary oversight responsibility for major projects in the organization. |

4.7.2 Some BOD Inadequacies Regarding Projects

• On the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) an “Owner’s Committee,” similar to a BOD, did not maintain oversight of the TAPS project, particularly with respect to strategic decisions on the project to include:

• The development of a master plan for the project

• Early integrated life-cycle project planning

• Design and implementation of a project management information system

• Development of an effective control system for the project

• Design of a suitable organization

• In the design and construction of nuclear power generating plants all too many utilities had BODs that neglected to exercise “reasonable and prudent” oversight over the planning and execution of nuclear power plant projects to support corporate purposes.

• The Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS) defaulted on interest payments due on $2.5 billion in outstanding bonds in part because of the failure of its directors. Communication at the senior levels of the company, to include the BOD, tended to be “informal, disorganized, and infrequent.”

However, on some nuclear power plant projects, BOD served in an exemplary fashion, such as in the case of the Pennsylvania Power and Light Company, where ongoing surveillance was conducted over the planning and construction of the Susquehanna nuclear plant project.

4.7.3 Key Responsibilities of BOD Regarding Projects

• Set an example for the ongoing review of projects that support organizational purposes.

• Provide senior managers guidance in the strategic management of the organization as if its future mattered.

• Ensure the strategic fit of ongoing projects with the strategic direction of the organization.

• Ensure that projects are recognized as building blocks in the design and execution of strategies, and that the linkages of projects with other initiatives in the organization are carried to help ensure the organization’s future.

• Maintain ongoing and regular review of major projects, and through doing this, help to motivate the general managers and project managers to do the same with respect to their projects.

• Be available to meet with key project stakeholders, such as project customers, should the need arise during the life of the projects.

• Review the key elements of the plan for major projects.

• Require formal BOD briefings or the status of the project at key points in the project’s life cycle.

• Visit the construction site on major projects. By so doing, an important message will be sent to the project team, and to other stakeholders on the project.

• Direct that the necessary independent audits are carried out for the projects that need such audits to determine their status and progress.

4.7.4 Project Information for the BOD

To carry out their responsibilities, the BOD members need certain information that is provided in an orderly and regular fashion. Examples of this information follow:

• Presenting information and issues on the project progress and status prior to BOD meetings so that the members have time to study the material prior to the meeting

• Providing for clear reporting on project information to the BOD members, avoiding burying the information in other corporate records to be reviewed at the BOD meeting

• Allowing time at the BOD meeting for a full discussion of the relevant project-related issues and decision matters

• Ensuring that the BOD members take the time and care to determine the “strategic fit” of major projects underway in the organization

4.7.5 Summary

In this section, the role of the BOD with respect to major projects in the organization was presented. A case was made that an ongoing surveillance over the planning and execution of projects would provide the BOD members’ insight into the effectiveness with which the organization is preparing for its future. Suggestions were made concerning how the role of the BOD regarding projects could be strengthened.

4.8 INTERNATIONAL PROJECTS

4.8.1 Introduction

International projects are defined as projects that bridge one or more national borders. International projects may be driven by one organization or they may be a partnership or consortium. The organizational relationships of the project owners drive the implementation.

International projects bridge more than national borders; there are cultural differences, time zone considerations, language differences, and monetary differences. Differences among the project participants increase the chance of miscommunication and misunderstandings. There are advantages to international projects that override any challenges to project planning and execution.

International projects are the wave of the future! |

4.8.2 International Project Rationale

Cooperative efforts between parties of different nations have significant benefits with only a few difficulties. At the national level, two countries may decide to develop cooperative research and development when it would be too costly for one nation to invest in the effort. Sharing the investment cost makes the project affordable.

Technology may drive the international project. When one country has advanced technology and another country needs that technology, joint cooperative efforts through projects will benefit both parties through lower cost and shorter time to obtain advanced technology.

Difference in labor costs is another reason for international projects. Where a project is labor intensive and the cost of labor is significantly less in another country, an organization may seek the less expensive resources. For example, some computer programming is one area that has been accomplished in India rather than the United States because of a significant difference in labor costs.

International projects can be cooperative efforts between organizations in different nations to build products for sale in both nations. Organizations work as a team to build different parts of a product, and both organizations market the product in their respective nations. This lowers the cost of the product and capitalizes on the capabilities of each organization.

Consortia with several different national organizations cooperating to build a product can also be an international project. The Concorde aircraft is an example of the cooperative efforts of nations to build a supersonic passenger plane that serves more than one national interest.

4.8.3 Types of International Projects

The different types of international projects may be defined by their characteristics. The general types will provide an understanding of the arrangements that may be used and of the existing thoughts on cooperation across borders. Figure 4.10 shows the more common types of international projects.

Descriptions of the types of international projects are below. These descriptions are representative of international projects at the top level, and the projects are typically tailored to meet the business needs of the stakeholders.

• Multinational projects—the cooperative efforts of two or more nations to build a product that serves the interests of both nations. The interested nations prepare and sign a cooperative agreement that defines the area and extent of cooperation. Typical business arrangements will be:

FIGURE 4.10 Types of international projects.

• Division of work between nations, i.e., contracts in countries

• Steering committee or management structure of the project

• Customs and duties waived

• Monetary unit that will be used

• Transfer of funds between national entities

• Intellectual property rights

• One organization with project elements in different nations—the efforts, controlled by one organization, across one or more national borders to achieve a specific purpose. This is used by major corporations when it is in their best interests to have a presence in one or more countries. Components of the project work will be performed in various countries under the control of the parent organization. The end product of the project affects all the organization’s elements in the participating countries.

• One organization with project (product) components built in several nations—the combined efforts of several different nations’ businesses to build a single project. The different national entities may be subcontractors or partners. The end product of the project is typically for one or more organizations, but not necessarily the participating organizations.

• A consortium of organizations—the efforts of several organizations in different nations, functioning as one for a single purpose, and having one or more projects. This is used when there is a need for several countries to develop a product or products that will serve their common interests, combining the capabilities of several organizations to meet a threat or interest. The end product of the project will typically serve all participants, but may be for profit.

There are unlimited number of arrangements that can be made for international projects. The more common types are simple and straight forward. When projects span national boundaries, there are inherent difficulties such as taxes, differences in monetary stability, and differences in quality practices. Keeping the projects simple and uncomplicated will facilitate completion.

4.8.4 Advantages of International Projects

International projects have many advantages that set the scene for more in the future. Figure 4.11 summarizes some of these advantages. Detailed discussion of the advantages is shown below.

• Financial. Richer and more developed nations can create work opportunities in emerging nations through international projects. Having the emerging nation, with low-cost labor, to perform labor-intensive functions is profitable. This also provides the emerging nation a source of revenue that builds on its economy.

• Hard currency transfer. Many nations have high inflation rates that exceed 1000 percent a year. When the project work is paid in “hard currency,” or currency that has a low inflation rate, the receiving organization has stability and leverage within its national boundaries. The stable currency provides a growth for the performing organization that cannot be achieved through projects internal to the borders.

FIGURE 4.11 Advantages of international projects.

• Technology transfer. Technology from one nation can be transferred to another nation through cooperative efforts of international projects. Technology transfer may be through providing information to another nation or through reverse engineering of the product. The net result is that a nation’s technology capital is increased through the transfer.

• Capitalize on existing technology. Another country may be significantly ahead in selected technology. Transfer of technology may take time and the need can be fulfilled by the owning nation. Therefore, the owning national organization can obtain the technology through contractual relationships.

4.8.5 Disadvantages of International Projects

International projects, in comparison with domestic projects, have disadvantages or additional challenges that an organization must address. These challenges can be overcome at a price and with knowledge that the advantages must outweigh the disadvantages. Figure 4.12 summarizes some of the disadvantages of international projects. Detailed discussion of the disadvantages is shown below:

FIGURE 4.12 Disadvantages of international projects.

• Technology transfer. While technology transfer can be an advantage, some nations place restrictions on the transfer of technology. Most recently, computer technology has been the subject of illegal transfers. From an organization’s perspective, it may not want to share its trade secrets in manufacturing and other proprietary information.

• Different time zones. Time zones may inhibit communication between the parent organization and the partners around the world. Communication windows may be limited to a few working hours a day or at night.

• Different work schedules. National holidays and work hours can limit communication windows and other opportunities. National holidays can also be celebrated at different times. Take for example Thanksgiving in the United States and Canada, celebrated in November and October respectively.

• Different languages. Languages can make it difficult to bridge the nuances and shoptalk of the technical field. American English, for example, can be significantly different from the English language spoken in Canada, England, Ireland, Scotland, Australia, New Zealand, and former British colonies.

• Difference in meeting agendas because of cultural differences. Meetings between Europeans, North Americans, and Asians can be significantly different in format. The silent time between an American ending his/her point and the time that the Asian responds can be uncomfortable for the American. However, this is a matter of respect by the Asian to wait until the other person is finished speaking.

• Measuring projects in own nation currency. Long-term projects using the local currency as measures of success may have difficulty when one currency is devalued through inflation or another currency increases in value. The project cost can vary significantly with changes to currency values.

• Quality standards. Quality of work is different across national borders. The materials available may be inferior and the workmanship can be at a low level of sophistication. These imbalances in quality can adversely affect the end product and its utility.

Depending upon the agreements between the different parties of an international project, there will be other disadvantages identified. Any organization should explore the differences between the cultures prior to initiating a new project. These differences, once identified, may be avoidable through seeking a common ground.

4.8.6 Developing an International Project Plan

Anticipating the advantages and disadvantages will give an organization important aspects an international project may encounter. Understanding the culture, the capability of another country, the materials available to perform the work, and the trained resources to perform the work is just a start. National laws, customs and duties, and transportation systems may be either favorable or unfavorable.

International projects between governments typically use an agreement that has approximately 20 paragraphs. These follow a standard procedure to ensure all areas are addressed. The agreements are morally binding, but not legally binding because of the lack of a court that has jurisdiction over the two or more nations. Organizations, however, should designate the country that has legal jurisdiction should negotiation fail.

Governments specify which language the agreement will be interpreted in and the dictionary that is used for all words. This provides a means of improving the communication as well as ensuring disputes are easier to settle. This does not always prevent misunderstandings because of the use of same words in different ways.

Planning for international projects must consider how the business will be conducted and the cultural aspects of all nationalities involved. It is interesting to note that many countries have regional cultures that vary within a country. Planning must account for the regional differences.

A checklist of items to address in the project plan would include the following:

• Technology and capacity of the people involved to complete tasks

• Skills and knowledge in the technical and managerial areas required

• Unique aspects of the culture that must be considered

• Transportation systems for shipping or delivery of the products

• Manufacturing materials in grade and quantity

• Quality assurance and quality control procedures

• Communication and reporting means, both tools and skills

• Political stability in the countries involved

• Laws regarding labor, taxes, duties, and fees

• Government indemnification of loss for all reasons other than force majeure

• Currency used for payments and monetary unit used for accounting

• Time zone differences and the affect on project reporting

• Holidays and on-work periods of all countries

• Interfaces between and among participants of the project

Project planning must be accomplished in one language to ensure the best understanding. Even among English-speaking countries, there will be differences in understanding the plan. The use of graphics and illustrations will promote understanding more than the use of words or semantic notations.

4.8.7 Summary

Both governments and many private organizations seek international projects to leverage the capabilities of another country. This leveraging provides benefits to both countries as well as providing specific benefits to the participating organizations. Typically, the leveraging is for financial savings or gain.

International projects have both advantages and disadvantages for an organization starting and executing a project that spans national borders. These advantages and disadvantages need to be considered when the business case is being developed.

Attempting to transplant one’s culture into another nation will be difficult and long term at best. Work ethic varies widely, from hard working to relaxed and lethargic. The manner in which the different national cultures approach business and interpersonal relationships varies from very formal to informal. Customs of respect for others also vary widely.

Communication may be the most challenging area for the project. Even within the English-speaking nations, there is a wide variation in the use of words and terms. When a language is translated, the nuances of such areas as technical language or shoptalk can be troublesome.

4.9 PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT FOR PROJECTS *

4.9.1 Introduction

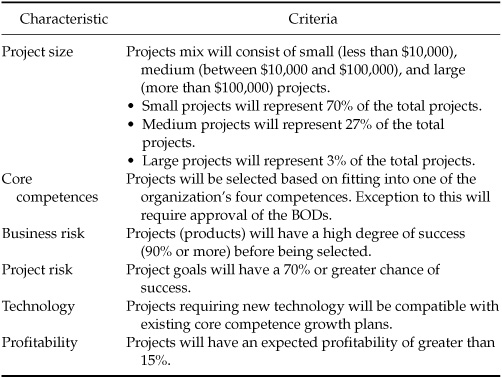

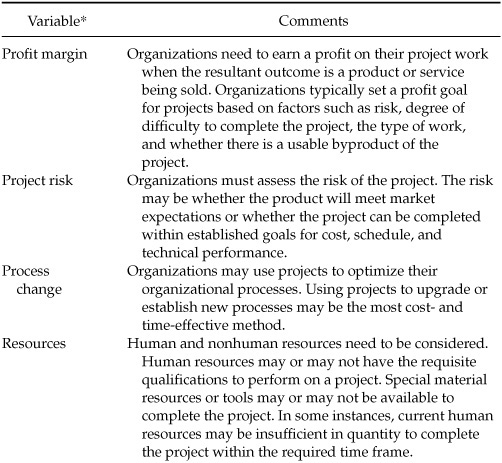

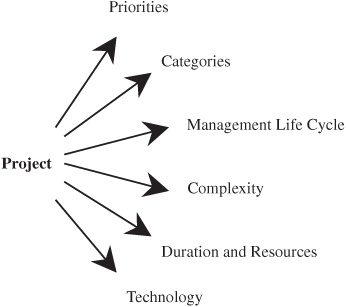

Portfolio management for projects uses the characteristics and attributes of projects to categorize and assess their value to the enterprise. This identifies specific characteristics of projects to determine the positive and negative factors that determine objective selection criteria. In turn, the selection of projects gives a balanced portfolio containing different characteristics that aligns with the enterprise’s strategic goals and operational needs.

Projects are typically categorized as small, medium, or large. These categories take on different meanings based on the organization’s definition of project size. Size is relative and is only one parameter for describing projects. There are other important characteristics that must be defined for the organization and used to build a portfolio of projects that support enterprise productivity and growth.

Portfolio management for projects is a strategic decision that determines favorable characteristics before a project is selected. Selected projects must have a strategic fit with the enterprises strategic objectives and goals and an organizational fit with the enterprise’s competences and be building blocks to the organization’s business line. Within the selected projects are other parameters that have favorable indications of success that create a balance between such characteristics as high, medium, and low risk.

4.9.2 Background on Portfolio Management

The financial community learned some time ago that the best position for investments is a diversification among stocks, bonds, and cash. Within the investments are different degrees of risk of loss and different degrees of opportunity for gain. A balance between the type of investment and the opportunity for gain or loss, consistent with an individual’s goals, comprises a portfolio. For example, an investment portfolio of $100,000 could be diversified as $75,000 in stocks, $23,000 in bonds, and $2000 in cash. An investor might be willing to accept the risk of gain or loss in the stocks and take advantage of the higher degree of return than one could earn on bonds or cash.

Project portfolio is the future of enterprise strategy. |

Project portfolios are gaining acceptance in the organizations to balance the types of projects with their relative benefits. Each organization needs a tailored portfolio that aligns with its strategic goals, operational needs, and organizational competence. Basic solutions of balancing size and risk to fit the organization’s capability could be a start. More sophisticated models may be needed to emphasize and capitalize on the organization’s direction and the rate at which it may need to grow.

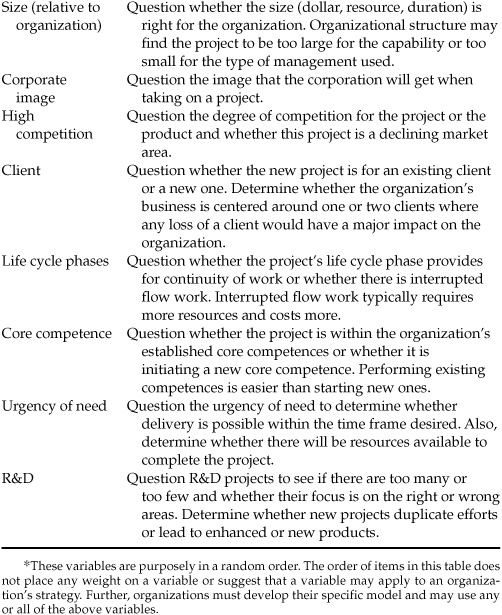

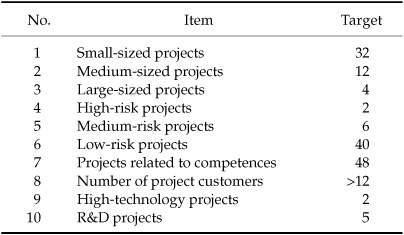

TABLE 4.4 Organizational Project Portfolio Model (Example)

4.9.3 Developing a Project Portfolio Model

The project portfolio model needs to be specific for an organization. Table 4.4 provides an example of a relatively fundamental model that could be a start point for an organization. The items listed are examples of areas that could comprise an organization’s portfolio model.

In Table 4.4, there are three sizes listed with targeted numbers of project defined for each size. There is a tendency to have the majority of projects in the small size, perhaps because they are quick to complete, the organization has a lot of experience in small projects, there is a need for a steady revenue stream, or this may be the majority of the market for this organization’s products and services.

Project risk is a major consideration in any endeavor. The three listed levels of risk are not further defined, but the trend is to target low-risk projects. Whereas low-risk projects may be the preferred type, typically low-risk projects are accompanied by low profit margins and called “bread and butter” work. High-risk projects, on the other hand, should have greater profit margins. Why is the project high-risk? It could be that this is a new technology for the organization or that a lot of uncertainty is associated with the project.