1

INTRODUCTION

In alignment with other PMI standards and practice guides, the Practice Standard for Project Estimating – Second Edition provides information on the activity of project estimating. This practice standard focuses on managing the estimating process and providing practical guidance geared toward project leaders, team members, and other stakeholders.

The audience for this practice standard includes, but is not limited to:

◆Portfolio/program/project managers;

◆Program and project team members;

◆Functional managers/operational managers,

◆Members of a program/project management office;

◆Program and project sponsors and stakeholders;

◆Educators and trainers of program and project management;

◆Analysts;

◆Scrum teams, scrum masters, and product owners;

◆Senior management and/or any decision maker responsible for approving the estimate; and

◆Individuals interested in program and project management and estimating in general.

This section provides an overview of this practice standard and includes the following subsections:

1.1 Purpose of this Practice Standard

1.2 Project Estimating Definitions

1.3 Scope of Project Estimating

1.4 Project Estimating and the Project Management Practice

1.5 Relationships among this Practice Standard and Other PMI Standards and Knowledge Areas

1.1 PURPOSE OF THIS PRACTICE STANDARD

The purpose of this practice standard is to define the aspects of project estimating that are widely recognized and consistently applied based on generally recognized good practices.

◆Generally recognized means the knowledge and practices described are applicable to most projects most of the time, and there is consensus about their value and usefulness.

◆Good practice means there is general agreement that the application of the knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to program and project management processes can enhance the chance of success over many programs and projects in delivering the expected business values, benefits, and results.

◆This practice standard has a descriptive purpose rather than one used for training or educational purposes.

The Practice Standard for Project Estimating – Second Edition covers project estimating as applied to portfolios, programs, projects, and organizational estimating. Project management estimating affects portfolios, programs, projects, and organizational estimating—directly or by aggregation—and often has identical processes, tools, and techniques. While portfolios, programs, and organizational estimating—specific or within an organizational project management (OPM) context—will be covered at a high level, the principal focus of this practice standard will be on projects.

Sections 6, 7, and 9 of A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) [1]1 (Project Schedule Management, Project Cost Management, and Project Resource Management) are the basis for the Practice Standard for Project Estimating – Second Edition. This practice standard is consistent with those sections, emphasizing the concepts relating to program and project estimating. It is also aligned with other PMI practice standards as described in Section 1.5.

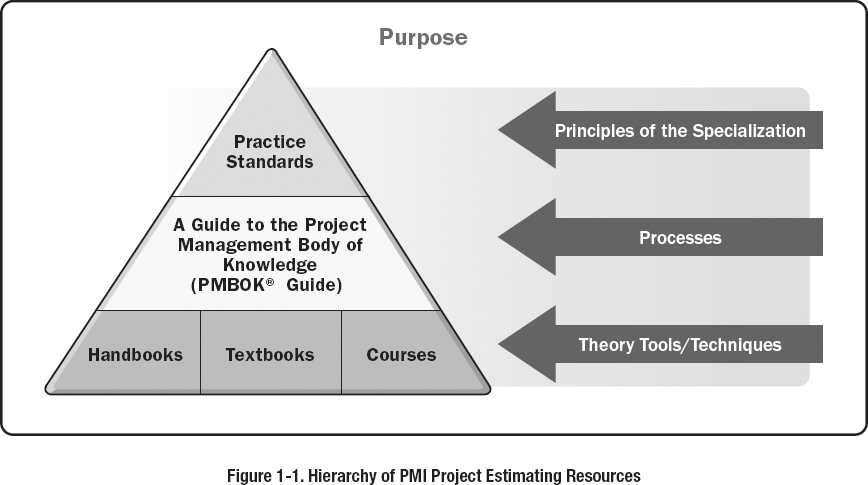

Figure 1-1 compares the purposes of this practice standard with those of the PMBOK® Guide and textbooks, handbooks, and courses. We recommend the PMBOK® Guide be used in conjunction with this practice standard because there are numerous cross-references to sections in the PMBOK® Guide.

This practice standard emphasizes concepts fundamental to effective, comprehensive, and successful project estimating. These concepts are stated at a general level for several reasons.

Different programs, projects, organizations, industries, and situations require different approaches to project estimating. Project estimating is an appropriate process to apply to programs and projects of varying sizes. In practical applications, estimating is tailored for each specific program or project. There are many specific ways of practicing project estimating that follow the concepts presented in this practice standard.

These concepts are applicable to projects carried out in a global context, reflecting the many business, industry, and organizational arrangements between participants. These arrangements include joint ventures between commercial and national companies, governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and the cross-cultural environments often found in these program and project teams.

Practitioners can establish procedures specific to their situation, program, project, or organization, then compare them with these concepts and validate them against good project estimating practices. In highly regulated industries or other environments, an independent project estimate may be mandated. Understanding the basis of those estimates, the methodologies, and the level of detail is important to project success.

1.2 PROJECT ESTIMATING DEFINITIONS

Important terms used in project estimating are defined as follows:

◆ Estimate. An assessment of the likely amount or outcome of a variable, such as project costs, resources, effort, durations, and the probability and impacts of risks or potential benefits.

◆ Basis of Estimates. Supporting documentation outlining the details used in establishing project estimates such as assumptions, constraints, level of detail, ranges, and confidence levels.

◆ Baseline. The approved version of a work product that can be changed only through formal change control procedures and is used as the basis for comparison to actual results.

These definitions are usually preceded by a modifier (i.e., preliminary, conceptual, feasibility, order-of-magnitude, or definitive).

Estimating, as described in the PMBOK® Guide and other related standards and practice guides, is comprised of three types of estimations, which will be elaborated on in this practice standard: quantitative, qualitative, and relative.

1.3 SCOPE OF PROJECT ESTIMATING

Project estimating is vital to successful portfolio, program, and project execution and the perception of success. Project estimating activities are a relatively small part of the overall program or project management plan and are first performed early in the program or project life cycle and repeated as the program or project progresses. The level of confidence is influenced by information available on, for example: market dynamics, stakeholders, regulations, organizational capabilities, risk exposure, and level of complexity. A program or project uses estimates along with the expected benefits to build the business case. Unrealistic estimates may compromise the ability of programs and projects to deliver expected value.

In addition to effort and resource estimation-based duration and cost estimations, project estimation is used in, but not limited to:

◆Contingency reserve definition;

◆Management reserve definition;

◆Organizational budgeting and allocation;

◆Vendor bid and analysis;

◆Make or buy analysis;

◆Risk probability, impact, urgency, and detectability analysis;

◆Complexity scenario analysis;

◆Organizational change management demands;

◆Capacity and capability demand estimation;

◆Benefit definition;

◆Success criteria definitions; and

◆Stakeholder management planning.

1.4 PROJECT ESTIMATING AND THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT PRACTICE

Even though estimates are initially developed at the onset of a program or project, it is important to think of estimating as a continuous activity throughout the program or project life cycle. The initial estimates are used to baseline the program and project efforts, resources, schedule, and/or cost. These estimates are then compared to the program and project benefit streams to determine feasibility. As the program or project progresses and more information is known, the estimates are continually refined and, subsequently, should become more accurate. This is consistent with the concept of progressive elaboration as described in the PMBOK® Guide and the Agile Practice Guide [2].

Additionally, the change control process is used to manage against the baseline cost and activity duration estimates. This continual process of reforecasting, based on new information and change controls, is why estimating is change driven and not a one-time event.

With the reported information during the project control phase, the project team will have enough data to refine the initial estimates and establish more accurate forecasts. This will create more effective action plans and allow a better understanding of program or project trends. There are many notable examples of final costs or schedules that were significantly different from the original estimate.

◆In 1914, the Panama Canal ran US$23 million under budget compared with 1907 plans.

◆In 1973, the Sydney Opera House was originally estimated at US$7 million. It was completed ten years late and the final cost came in at AU$102 million.

◆In 1988, the Boston Big Dig was estimated to be US$2.2 billion. It was delivered five years late at a cost of US$14 billion, more than six times the estimate, due in part to flooding that destroyed all work and equipment, which was overlooked in the risk identification estimation steps.

◆In early 1993, the London Stock Exchange abandoned the development of the Taurus program after more than 10 years of development effort. The Taurus program manager estimates that it cost the City of London over £800 million when the program was abandoned. The original budget was slightly above £6 million. Taurus was 11 years late and 13,200 percent over budget, without any viable solution in sight.

◆In 1995, the Denver International Airport opened 16 months late and was an estimated US$2.7 billion over budget.

◆The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) launched the Advanced Automation System (AAS) program originally estimated to cost US$2.5 billion with a completion date of 1996. The program, however, experienced numerous delays and cost overruns, which were blamed on both the FAA and the primary contractor. According to the General Accounting Office (GAO), almost US$1.5 billion of the US$2.6 billion spent on the AAS program was completely wasted. One participant remarked: “It may have been the greatest failure in the history of organized work.”

◆In 1996, the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, was planned to be US$1.2 billion. The final cost was US$1.6 billion.

◆In 2009, the London Crossrail project was estimated at £14.8 billion and scheduled to be completed in 2019. The project suffered severe cost overruns and is predicted to need an additional £2 billion in project finances.

◆In 2011, the Mars Science Laboratory Rover was budgeted to cost US$1.6 billion. The final cost, when completed, was approximately US$2.5 billion.

◆The new Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), started in 2006 and scheduled to be completed in 2010, was originally estimated at €2 billion. The updated estimate of the project is €7.3 billion and projected to be completed in 2020, ten years late.

1.5 RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THIS PRACTICE STANDARD AND OTHER PMI STANDARDS AND KNOWLEDGE AREAS

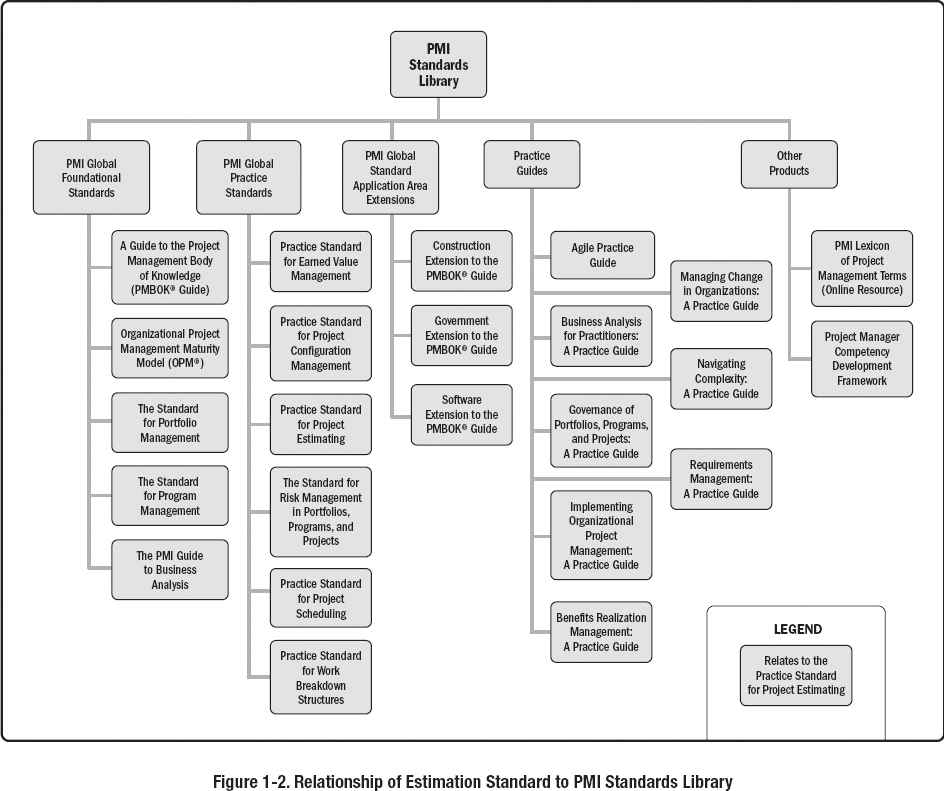

Estimating has connections to many other disciplines within program and project management, and it is an iterative process that occurs throughout the project life cycle. Figure 1-2 illustrates the relationships among this practice standard and other PMI standards and Knowledge Areas. Estimation is tightly integrated with the Project Scope Management, Project Schedule Management, Project Cost Management, and Project Resource Management Knowledge Areas.

1.5.1 THE PMBOK® GUIDE

The sections in the PMBOK® Guide related to estimating are:

◆ Section 3 on The Role of the Project Manager

■ Section 3.5.4 on Integration and Complexity. Perceived complexity impacts the level of estimation confidence.

◆ Section 4 on Project Integration Management. Estimating is a critical aspect of creating the project management plan and performing integrated change control.

■ Section 4.6 on Perform Integrated Change Control. The process of reviewing all change requests; approving changes and managing changes to deliverables, project documents, and the project management plan; and communicating the decisions. This process reviews all requests for changes to project documents, deliverables, or the project management plan and determines the resolution of the change requests.

◆ Section 5 on Project Scope Management. The project scope is defined by the work packages that would be used for future estimates and the sizes of those activities, which are estimated for resources, durations, and cost.

■ Section 5.4 on Create WBS. The process of subdividing project deliverables and project work into smaller, more manageable components.

◆ Section 6 on Project Schedule Management. Develop Schedule is a process in the Project Schedule Management Knowledge Area that takes place in the Planning Process Group. Schedule management is a continuous and iterative process that requires reforecasting and refinement of the activity resource and activity duration estimates throughout the project. In an agile project, the story points are used to estimate the effort and the number of iterations.

■ Section 6.2 on Define Activities. The process of identifying and documenting the specific actions to be performed to produce the project deliverables.

■ Section 6.4 on Estimate Activity Durations. The process of estimating the number of work periods needed to complete individual activities with the estimated resources.

■ Section 6.5 on Develop Schedule. The process of analyzing activity sequences, durations, resource requirements, and schedule constraints to create a schedule model for project execution and monitoring and controlling.

◆ Section 7 on Project Cost Management. Determine Budget is a process in the Cost Management Knowledge Area that takes place in the Planning Process Group. Project Cost Management is a continuous activity that requires reforecasting and refinement of the cost estimates throughout the project.

■ Section 7.2 on Estimate Costs. The process of developing an approximation of the monetary resources needed to complete project work.

■ Section 7.3 on Determine Budget. The process of aggregating the estimated costs of individual activities or work packages to establish an authorized cost baseline.

◆ Section 8 on Project Quality Management. Quality is embedded across the estimating life cycle, including the incorporation of quality requirements, the continual monitoring of estimates, and taking lessons learned back into the estimating model. Includes the estimate of the cost of quality.

◆ Section 9 on Project Resource Management. Estimated activity durations may change as a result of the competency level of the project team members and availability of, or competition for, scarce project resources. Cost estimates should also include possible human resource rewards and recognition bonuses.

■ Section 9.1 on Plan Resource Management. The roles and responsibilities of who will make the estimates are defined.

■ Section 9.2 on Estimate Activity Resources. The process of estimating team resources and the types and quantities of materials, equipment, and supplies necessary to perform project work.

◆ Section 10 on Project Communications Management. Because there are many assumptions in creating an estimate, varying levels of information and confidence, as well as ever-changing forecasts, communications management is a critical component of managing estimates and expectations. Communications entails soliciting information as well as delivering it, and this is a key consideration for obtaining reliable data on which estimates can be based.

◆ Section 11 on Project Risk Management. Estimates are created based on an incomplete set of information, so there is always inherent risk involved that requires management. The impact and likelihood of each anticipated event are estimated in the risk register.

■ Section 11.1 on Plan Risk Management. The process of defining how to conduct risk management activities for a project.

■ Section 11.2 on Identify Risks. The process of identifying individual project risks as well as sources of overall project risk, and documenting their characteristics.

■ Section 11.3 on Perform Qualitative Risk Analysis. The process of prioritizing individual project risks for further analysis or action by assessing their probability of occurrence and impact as well as other characteristics.

■ Section 11.4 on Perform Quantitative Risk Analysis. The process of numerically analyzing the combined effect of identified individual project risks and other sources of uncertainty on the overall project objectives.

■ Section 11.5 on Plan Risk Responses. The process of developing options, selecting strategies, and agreeing on actions to address overall project risk exposure, as well as to treat individual project risks.

◆ Section 12 on Project Procurement Management. Procurement management includes acquisition of services or products that include resource, duration, cost, and quality implications.

■ Section 12.1 on Plan Procurement Management. The process of documenting project procurement decisions, specifying the approach, and identifying potential sellers.

◆Cost estimates and activity resource requirements are inputs to the procurement approach and are used to evaluate the reasonableness of bids. Often, the project estimate becomes the project budget after the contract negotiations.

◆ Section 13 on Project Stakeholder Management. Program and project success stakeholder expectations are mostly based on implicit or communicated estimations. Therefore, good estimations communicated in a timely manner are critical to perceived program and project success.

■ Section 13.3 on Manage Stakeholder Engagement. The process of communicating and working with stakeholders to meet their needs and expectations, address issues, and foster appropriate stakeholder involvement.

1.5.2 PRACTICE STANDARD FOR EARNED VALUE MANAGEMENT [3]

Managing earned value starts with specifying the planned value for specific increments of work. Earned value is also a diligent way of monitoring and verifying the project actuals and forecasting and comparing them to the project estimates.

1.5.3 PRACTICE STANDARD FOR WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURES [4]

The work breakdown structure (WBS) defines work packages at a level of detail that enables an acceptable level of confidence for effort and resource estimation-based cost and duration estimations. The WBS also establishes essential relationships among key assumptions for scope, scale, and performance requirements at all levels used to support the various estimating methods. Finally, the WBS allows for estimation consolidation up to the program and/or project level.

1.5.4 PRACTICE STANDARD FOR SCHEDULING [5]

The schedule is created based on activity durations, derived from effort and resource estimations.

1.5.5 THE STANDARD FOR RISK MANAGEMENT IN PORTFOLIOS, PROGRAMS, AND PROJECTS [6]

Risk management uses qualitative and/or quantitative estimations and impacts all estimations as they are based on assumptions and uncertainty. Estimation is also used to define urgency and detectability of risks.

1.5.6 THE STANDARD FOR PROGRAM MANAGEMENT [7]

The sections in The Standard for Program Management related to estimating are:

◆ Section 8.1 on Program Definition Phase Activities and Section 8.2 on Program Delivery Phase Activities. These sections highlight the program management processes related to program and project estimating and assessment. Risk mitigation, for example, often results in additional work and cost, which need to be included as part of the estimate.

■ Section 8.1.1.3 on Program Initial Cost Estimation. A critical element of the program's business case is an estimate of its overall cost and an assessment of the level of confidence in this estimate.

■ Section 8.1.1.7 on Program Resource Requirements Estimation. The resources required to plan and deliver a program include people, office space, laboratories, data centers or other facilities, equipment of all types, software, vehicles, and office supplies. An estimate of the required resources—particularly staff and facilities, which may have long lead times or affect ongoing activities—is required to prepare the program business case and should be reflected in the program charter.

■ Section 8.1.2.3 on Program Cost Estimation. Program cost estimating is performed throughout the course of the program. A weight or probability may be applied based on the risk and complexity of the work to be performed in order to derive a confidence factor in the estimate.

■ Section 8.2.3.2 on Component Cost Estimation. Because programs have a significant element of uncertainty, not all program components may be known when the initial order-of-magnitude estimates are calculated during the program definition phase. It is a generally accepted good practice to calculate an estimate as close to the beginning of a work effort as possible.

◆ Section 8.3 on Program Closure Phase Activities. This section provides significant input for the Estimating Process Improvement stage as described in Section 6, Improve Estimating Process, of this practice standard.

1.5.7 THE STANDARD FOR PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT [8]

Estimating impacts the portfolio life cycle as well as all portfolio management performance domains. Portfolio management practitioners, members of a portfolio management office, consultants, and other professionals engaged in portfolio management need to be aware of the relevance of selecting the proper estimating tools and techniques and the impact of estimating outputs within the portfolio performance domains, as described in the following sections in The Standard for Portfolio Management:

◆ Section 3 on Portfolio Strategic Management. Portfolio strategic management is the management of intended and emergent initiatives. It supports strategic thinking, is the basis for an effective organization or business unit, and assesses if the right thing is being done. The key terms in the context of estimating are:

■ Portfolio funding. Understanding the financial resources that stakeholders are willing to commit and the expected return on investment is critical in structuring the portfolio; and

■ Portfolio resources. Understanding the available resources committed to the portfolio assists the portfolio management team in structuring the portfolio while taking resource constraints and dependencies into consideration.

◆ Section 5 on Portfolio Capacity and Capability Management. The objective of portfolio capacity and capability management is to ensure that the portfolio's capacity and capability demands are in alignment with portfolio objectives, and that the organization's resource capacities and capabilities can support or meet those demands.

◆ Section 7 on Portfolio Value Management. Portfolio value management ensures that investment in a portfolio delivers the required return as defined in the organizational strategy. The investment and required return are estimations. Overestimating the investment may truncate further investments. Overestimating the return will create expectations that will destroy the perception of component success or even lead the organization to authorize components, which will not be able to produce the necessary return. The same concept is applicable to underestimating investment or return.

◆ Section 8 on Portfolio Risk Management. Managing risks below the portfolio level is usually viewed as exploiting opportunities and avoiding threats. However, when dealing with complexity at the portfolio level, the simple approach of avoiding threats and exploiting opportunities may not result in a complete balancing of portfolio risks. Risk and change should be embraced and navigated within an environment of complex interactions. Within this nonlinear environment, the portfolio management team addresses specific portfolio-level risks with the goal of optimizing value for the organization.

1.5.8 THE STANDARD FOR ORGANIZATIONAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT (OPM) [9]

Resource gap analyses, expert judgment, effort and resource estimation-based duration, cost estimations, and other estimations are used to develop OPM implementation or improvement plans. Capacity estimation helps to understand the viability of OPM initiatives.

1.5.9 NAVIGATING COMPLEXITY: A PRACTICE GUIDE [10]

Navigating Complexity: A Practice Guide and the impact of complexity on uncertainty and estimations are mentioned in all standards and the Agile Practice Guide. Complexity should be considered when estimating and communicating the level of confidence for estimations.

1.5.10 AGILE PRACTICE GUIDE

The Agile Practice Guide describes a context of program and project management with a recognized high impact on most program and project management aspects, including estimating. Agile practices and life cycles are termed adaptive practices and life cycles and generally embed risk mitigation practices that are merged with estimation and work practices. The merge of these practices leverages the speed of rough order of magnitude (ROM) estimates, such as relative estimation.

1.5.11 THE PMI GUIDE TO BUSINESS ANALYSIS (INCLUDES: THE STANDARD FOR BUSINESS ANALYSIS) [11]

The PMI Guide to Business Analysis (Includes: The Standard for Business Analysis) is a basis for business analysis as a complementary activity to project management and is heavily integrated into estimation practices. Section 5 of this guide, Stakeholder Engagement, contains relevant material in subsections that parallel estimation activities conducted by a business analyst. In addition, Section 7, Analysis, of The PMI Guide to Business Analysis (Includes: The Standard for Business Analysis) discusses using estimation techniques in product backlogs.

1.6 SUMMARY

This practice standard is intended for portfolio, program, and project management practitioners and other stakeholders. This practice standard covers the aspects of project estimating that are recognized as good practice in most portfolios, programs, and projects most of the time.

This practice standard focuses on resource and effort estimations, duration and cost estimations, capability and capacity estimations, risk urgency, impact, probability and detectability estimations, complexity assessments, and other estimation-related themes. Project estimating is important because of the many direct linkages to other aspects of portfolio, program, and project management.

The management concepts of project estimating described in this practice standard may be tailored based on the specifics of a program or project. Experience indicates that perceived program and project success directly correlates with the appropriate application of project estimating practices throughout program and project life cycles. This practice standard includes all project life cycles, including predictive and adaptive life cycles. Adaptive life cycles are agile, iterative, or incremental and are also referred to as agile or change-driven life cycles.

This practice standard uses the bicycle case study, included in other PMI standards and practice guides, to demonstrate the use and impact of project estimating.

1 The numbers in brackets refer to the list of references at the end of this practice standard.