Evaluating Performance

,Begin to synthesize your thinking into an overall impression of your employee’s performance during the year. Review the information you’ve gathered, sift through the data you’ve collected, and make some informal notes. Look for common themes, and give equal consideration to positive results and shortcomings. Has your employee excelled, delivering more than you expected? Has he met your expectations, delivering a solid but not exemplary performance? Or have there been problems, with some goals unmet and results undelivered? It’s time to come to a point of view and record it in writing so that you can share it with your employee—and save it for future reference.

Assess results

In theory, assessing the results of your employee’s work is simple. Just ask yourself, Has he met the goals set for him since his last review? The easiest achievements to evaluate are those that are quantitative, such as numbers of products shipped, new accounts closed, or reports written. But fewer and fewer jobs today produce easily quantifiable results. To make an objective assessment of your employee’s performance on the more qualitative aspects of his job, focus your assessment on his behaviors, using examples for support.

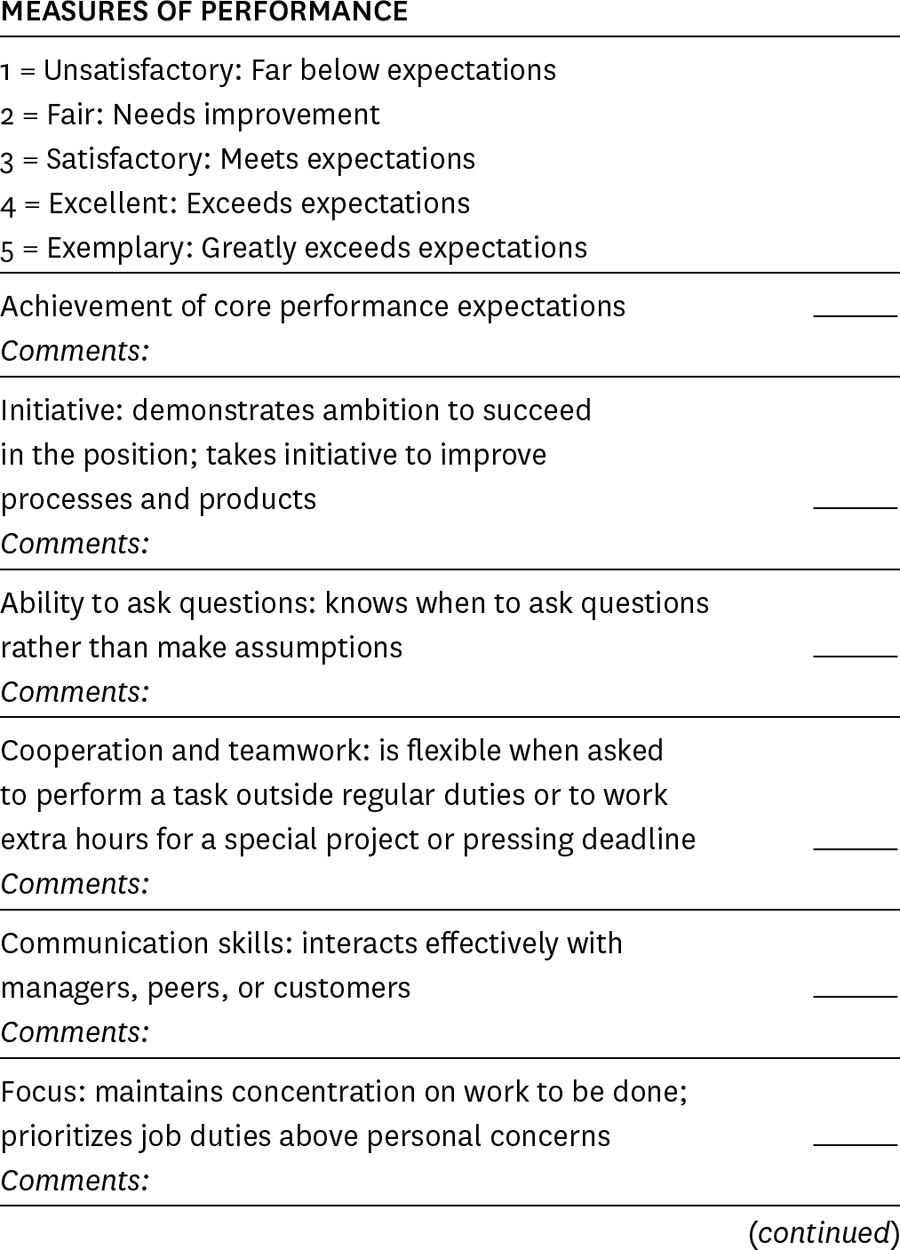

Determine which behaviors are most critical for your employee’s successful performance, perhaps by referring back to his job description. For someone in a customer-service position, for example, communication skills are critical, while for a software developer, coding skills are more important. Your organization may also suggest key behaviors or competencies that you’ll want to track. For instance, in a company that prizes innovation, creative thinking will be a valuable asset. Beyond the questions that are specific to the position and your company, consider these general attributes suggested by performance management expert Dick Grote:

• Initiative: Does the employee demonstrate ambition or take initiative to improve processes and products?

• Ability to ask questions: Does the employee know when to ask questions rather than make assumptions?

• Cooperation and teamwork: Is the employee flexible when asked to perform a task outside his regular duties or to work extra hours? Does he volunteer to pitch in when the team is short-handed?

• Communication skills: Does the employee communicate adequately with managers, peers, and customers? Have any problems been created or solved because of the employee’s communication skills?

• Focus: Does the employee maintain focus and prioritize job duties effectively?

• Productivity: Does the employee work effectively and meet deadlines?

• Knowledge: Does the employee demonstrate an acceptable level of knowledge to perform his job?

• Reliability: Does the employee consistently demonstrate dependability and competence?

• Improvement: Has the employee improved in areas identified as needing development on his previous evaluation?

As you evaluate the employee in each of these areas, look through the materials you’ve gathered and jot down notes and specific examples. Then consider what factors may have played a role in your direct report’s performance. You’ll work with him in the discussion itself to sort out many of these root causes (see “Addressing performance gaps” in the next chapter), but in advance of the meeting, assess whether you have contributed to any achievements or performance issues.

Consider your role in the employee’s performance

Though it’s often difficult to see (or admit), some unsatisfactory performance can be linked to issues with the individual’s supervision. Be open to the possibility that your actions or behavior may be a factor in an employee’s successes or failures. Honestly assessing how you may have affected an employee can help you evaluate his performance more accurately and fairly.

Some managers, for example, unwittingly erode employees’ self-confidence by failing to sufficiently praise good performance or by delivering overly harsh criticism, which diminishes motivation and achievement. Some poor performance can be attributed to a common dynamic that organizational behavior and change management experts Jean-François Manzoni and Jean-Louis Barsoux call the “set-up-to-fail syndrome.” In this situation, the manager and direct report start with a positive relationship that gradually worsens because of a poor result—a missed deadline, perhaps, or a lost client. The manager begins to micromanage, and the employee, suspecting his supervisor’s reduced confidence, stops doing his best work and avoids making decisions. The manager views this new behavior as additional proof of mediocrity and tightens the screws further, continuing the cycle.

When evaluating areas that are unsatisfactory in your employee’s work, consider how you may have contributed to or interfered with an individual’s success by asking yourself:

• Have you provided your employee with adequate assistance, training, and resources?

• Have you been clear in your expectations and detailed in your direction?

• Have you set realistic deadlines and established clear priorities?

• Have you tried to motivate the individual to excel?

• Have you been too hands-off, providing insufficient feedback or guidance?

• Have you been too involved, not allowing the individual a chance to succeed independently?

Perhaps, in retrospect, you see that you slowed your employee down by micromanaging, or that he could have made faster progress with more frequent feedback and guidance. Thoughtfully considering your own role in his performance will help you view his work more realistically and make your overall assessment more objective, so you’re not assigning blame unnecessarily and you can take the appropriate corrective measures in the future.

Document your impressions

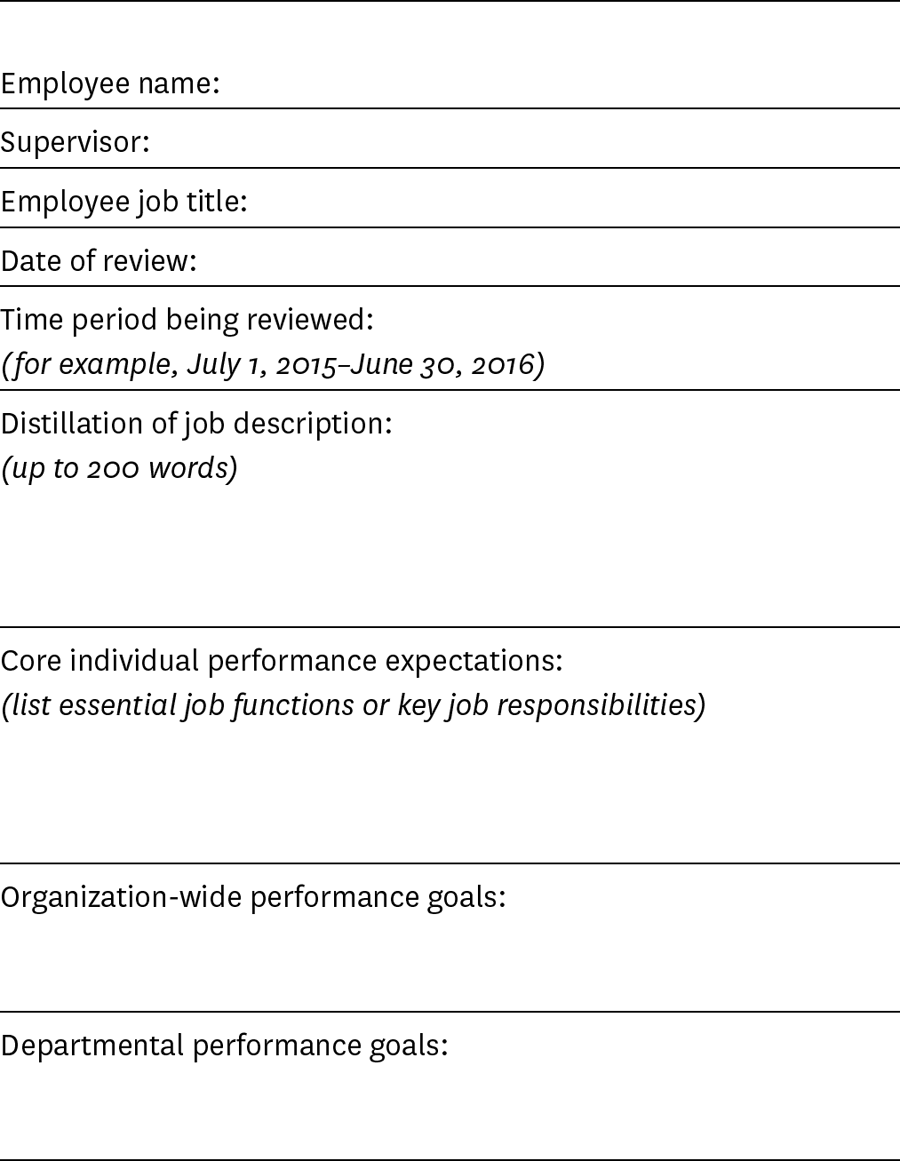

Once you have analyzed your employee’s performance, record your feedback in a way that can be shared and saved. When preparing a formal written assessment, refer back to your company’s guidelines so you’re adhering to the appropriate format. If your company does not have a standard form, create one using Table 1, “Annual performance review template,” at the end of this chapter.

Your organization may require you to provide a general rating of the employee’s performance, individual ratings of specific aspects of their performance, or a combination of ratings and qualitative information. Follow the instructions given to you, but don’t be constrained by the format of the form. Instead, adapt or amend it so you can tell the whole story. Your employee will find your observations, comments, and examples more useful than a numeric rating alone. Include attachments—comments too long to include on the form, or the employee’s development plan from the previous year—if they will enrich your evaluation.

Record your observations about your employee’s job performance as objectively as possible, and tie your conclusions to hard data. Provide evidence of progress (or lack thereof) by connecting accomplishments with established goals: “Derek increased sales by 7%, which exceeded his goal of 5%.” “Laura reduced her error rate by 20%; her goal was 30%.” Then your employee can easily grasp the assessment criteria and recognize the evaluation as fair.

Also include specific examples. The more information you can provide, the more likely the employee will be to repeat and even improve on positive behaviors—or correct less positive ones. Use the most telling examples to make your point in your written evaluation, and save the rest for your review session in case you need to support your judgment during the conversation. These examples should include:

• Details about what you observed. Let’s look back at Theo, the customer service representative in the previous chapter. Theo has more than doubled the orders he’s filled over the past year, now that he’s learned how to use the new customer database. But don’t just say that; back it up with detail. For example, write: “Last year Theo filled 15 orders per day. This year his average was up to more than 30 per day. He also asks fewer questions now that he’s effectively using the customer database.”

• Supporting data, such as reports or 360-degree feedback: “Siobhan helped Theo learn how to use the new customer database, and she reports that he’s using it on a regular basis.”

• The impact on your team and organization: “After Theo learned how to use the new database, he no longer had to rely on colleagues to find out pertinent information. The whole team began fulfilling orders more quickly because they were answering fewer questions from him, which improved cash flow for the organization.”

Expressing your observations as neutral facts rather than judgments is particularly important when giving negative feedback. For example, “Theo doesn’t seem to care about customers” negatively characterizes Theo rather than describing his behavior. “Theo doesn’t know how to talk to difficult customers” also isn’t helpful, because it infers a lack of knowledge instead of identifying a skill that Theo can improve upon. On the other hand, “Theo received five complaints from extremely unsatisfied customers,” is more objective and specific to a particular job requirement.

When giving positive feedback, on the other hand, combine specific achievements with character-based praise. For example: “With the new accounts she generated, which delivered $1.25 million in business, Juliana exceeded the goal we set for her last July by 27%. Her creativity and perseverance drove her to look beyond the traditional client base; she researched new industries and networked at conferences to find new customers.” Acknowledging the traits and behaviors that made those results possible will show your direct report that you see her as an individual—which can generate pride and boost motivation.

Supporting your assessment with specific examples and details not only makes it more likely that the employee will be able to hear and learn from your feedback, it also mitigates any possible legal ramifications in particularly egregious situations. If an employee’s work is beginning to suffer, or if you suspect that you might need to dismiss someone due to poor performance, it’s vital that you document the individual’s behavior and the steps you’ve taken in attempting to correct it. As a rule of thumb, include in your evaluation only statements that you’d be comfortable testifying to in court. If you have any questions about legal ramifications, consult with your human resource manager or internal legal team.

Finally, write down the three things the employee has done best over the course of the year and the two areas that most need improvement. Ask yourself, “What’s the single most important takeaway I want the employee to remember?” Distill your message down to a single key idea—your overall impression of his performance. These few points will determine the overarching message that you want to convey in the review discussion, and having them documented will prevent you from forgetting any important points when you’re in the moment.

TABLE 1 Annual performance review template

Adapted from Dick Grote, How to Be Good at Performance Appraisals (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2011), 98–100.