3. It's all About Components

What are business components? What happens to an industry when its core processes and services become interchangeable, and what does a componentized business look like? What are the advantages of componentization? In this chapter, we examine these what's, why's, and how's of componentization and identify both the growth opportunities that they open up and the problems that they create.

Redefining Business Components

Business components are the equivalent of interchangeable manufacturing parts but are instead composed of processes, functions, services, and activities—capabilities. A business component is a set of related capabilities that companies carry out on a daily basis. A company might define "marketing" as a component, but so is "advertising," and within advertising is "copy writing." This scoping decision—handling marketing as a total component, versus decomposing it to advertising or breaking it down into more subelements—is determined by its deployment as a capability in the firm's value webs, rather than its function in internal operations.

In automobile manufacturing, the engine might be considered a component in one instance, while in another it's the spark plug. By outsourcing the manufacturing of the X3, BMW will focus on engine design while outsourced manufacturer Magna Steyr and its value web of parts suppliers will meticulously break down every element to what may be thought of as the atomic level.

Management must decide on the types of componentized capabilities the firm wants to use to build its profitable growth and the roles these capabilities play in its value webs. The practical steps of deciding on the business priorities for componentization are addressed in later chapters. There are three levels of components: Composite, Bundled, and Atomistic.

Composite components are marketing, supply chain management, or human resource administration. They are capabilities that a company accesses as a whole from a value web partner that generally brands them as a service. If the company plans to outsource them, there is no reason to break them down into components; the only need is to make sure there are standardized interfaces, which may require investment in process improvement and IT platforms.

Bundled components are clusters of processes, such as advertising within marketing, procurement within supply chain management, and new-hire document processing within HR administration.

Atomistic components are the specific activities within processes.

Regardless of the chosen level of definition, business components include the people, systems, and any other resources necessary to accomplish the result that justifies calling it a "capability." Companies create growth, build value, and avoid commoditization only by linking these capabilities together within the organization, and between organizations in a value web. For a set of business activities or processes to be a component, it simply must have a standardized interface with other components. Without the interface, the business parts are not interchangeable, and you have the lurking danger of proprietary interfaces. That systematization and packaging is not easy to achieve; it has occupied the auto industry for over a decade and dominated the restructuring of the consumer electronics industry.

Standardized interfaces usually mean that no one party controls the use of the interface. Instead, they open up competition by making one firm's processes, products, or services substitutable for another's and therefore inevitably accelerate commoditization, fueled by the pressures for "efficiency" and cost reduction. Companies that can maintain a proprietary interface thrive—for a while. They make their own parts, control their value chains, set terms for suppliers, generate a premium price, and own their unique designs. Once standardized interfaces move to the forefront, these proprietary firms are pushed into a defensive position and eventually lose their leadership position. To be fair, this proprietary position used to work in the era of value chains, as AT&T's control of who could connect devices to its network showed. Now, anyone can connect just about anything to the public phone system.

Standardized interfaces remove value chain control and open up value web coordination. Credit cards are an example of such interfaces; you can use any provider's card at an ATM, airline self-check-in machine, or over the Web. You can also switch providers routinely and automatically. The billions of dollars of Internet e-commerce would not happen without the credit card as a payment mechanism and the menu for entering your card data as standardized.

An Industry Moves to Interchangeable Business Parts

The U.S. mortgage business provides an instructive starting point for discussing the nature and impact of componentization, but we could have picked airline reservations, credit cards, Internet portals, car manufacturing, or retailing instead. The mortgage industry is extremely fragmented1 with real estate agents, mortgage brokers, mortgage bankers, appraisers, title companies, mortgage insurers, document specialists, county recorders, investors, and, of course, the buyers and sellers on behalf of whom this is all meant to work.

There is no way that such a complex set of interactions could ever be "integrated," "streamlined," or "re-engineered," but it is being synchronized in new ways through interchangeable process parts and standardized interfaces. The industry has long been built upon separate organizations performing different roles in the mortgage creation process. Customers may not even see the banker or mortgage broker with whom they originate the process or the appraiser who visits the property, nor be fully aware of the credit checks that will be made by a third party. Once their mortgage is approved, customers write a check or authorize an electronic payment to the institution that manages their payment processing that, over the life of the loan, may change any number of times. They also have to fill out an application and sign a pile of documents at closing. That is just the tip of the iceberg. Behind the scenes, the mortgage business has long been a muddle of very unstandardized definitions, documents, procedures, pricing, time-tables, and processes.

There are two giant players, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, that are intermediaries in the flow of mortgage loan financing, issuing, securitization, and reselling. Once these two organizations implemented procedures based on the XML standard for document and data interchange, they forced the entire industry to a common interface, setting the stage for a new mortgage industry built on interchangeable business parts. This was not automatic or fast, but it was inevitable. Industry administrative costs were escalating and margins were under pressure in an era of falling interest rates and rapidly increasing refinancing. Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae supported the voluntary industry trade association, MISMO, which began introducing initiatives in 1999.2 This resulted in agreements on rationalization and standardization of 3,000 business terms in a data dictionary, agreements on legally binding submission and acceptance of legally binding electronic documents, and the adoption of XML and XHTML (a variant of HTML that's XML compatible).

Once Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae implemented the MISMO interfaces, other companies could not afford to ignore the innovation. They needed to do business with the organizations, and once the other large players standardized, the market became componentized. The previous masses of forms and procedures were now communication and processing packages. The industry built capabilities that enabled large and small players to benefit from the electronic component. Freddie Mac's software application, Loan Prospector, became the hub in a hub-and-spoke web and included such new componentized services as online automated underwriting and vendor services (appraisals, flood and title insurance, and so on). Fannie Mae's Desktop Originator3 provides services for credit unions, mortgage brokers, and other industry groups. It added components for single family lending and servicing, including investor accounting, secondary marketing, and shipping and delivery.

The same standards are being adopted across the ecosystem. Internet-based leaders, such as Lending Tree, make their money mainly from electronic referral fees to 150 lenders of, typically, $450, while seeking the best deal for its customers. The volume of online mortgages grew from around $20 billion in 2000 to over $160 billion in 2001, and Washington Mutual alone expected to handle $100 billion in 2004.4 These are small numbers in comparison to the total market, but even if they grow at the typical e-commerce rate of 20 percent annually, they are already adding to the commoditization of basic mortgage services and processing.

These trends and their results are ones that occur again and again and will force more and more industries into consolidation and restructuring. Mortgages are a $6.3 trillion industry. The mortgage ecosystem restructuring has been massive and transformative, yet there was nothing innovative—no sense of radical new ideas, players, or products. All that happened was that paperwork and processes for handling loan origination were turned into components via standardized interfaces.

In 1994, the top-10 mortgage lenders had a 25 percent market share, and the top 25 had a 40 percent market share. Now the top 5 have 50 percent of the market, and the top 25 have a 79 percent market share. Componentization facilitates advantages of scale and process rationalization. It removes differentiations in products and services that previously compensated for cost inefficiencies. It also eliminated the need for intermediaries, such as small brokers who were replaced by an electronic link to one of the giants. New intermediaries will emerge, but they will do so by competing on new capabilities, not old ones.

This summary of one of the largest industries in the economy illustrates a pattern that is similar to the changes in travel agencies and credit cards. In all these instances, the winners win big, and less agile companies and smaller players fall into commodity hell.

Li & Fung: A Growing and Growing Componentized Business

The home mortgage example encompasses an industry. The more immediate innovation opportunity is for a company to exploit the componentization and commoditization link before it is pushed into catch-up or commodity hell.

Li & Fung is a highly profitable, rapidly growing global apparel firm that "detaches critical links in the apparel industry's supply chain and finds the best solution for each step." In other words, its entire business is built on components that it deploys, integrates, and synchronizes on behalf of 7,500 factories—none of which it owns or manages but that add up to a million-employee capability—and 350 customers, mostly leading U.S. and European retailers.

The power of this on demand integration is illustrated by an example from The Limited retail chain. It informed Li & Fung that it needed 100,000 garments. There was a small catch: Styles and colors couldn't be specified until the very last minute. No problem whatsoever for Li & Fung. It coordinated its value web, reserving dyes from one supplier, locking in weaving and cutting capacity from others, and delivering—or rather having someone else deliver—the goods in five weeks, versus the typical three months.

As a broker, Li & Fung was increasingly squeezed by the power of large buyers and factories, quite literally caught in the middle. Now, Li & Fung is what writer John Hagel describes as a supply chain "orchestrator."5 Its response to the business squeeze was to remove itself from the role of direct intermediary, connecting buyers and sellers, and instead coordinate multiple levels and parties. "To produce a garment, the company might purchase yarn from Korea and have it woven and dyed in Taiwan, cut in Bangalore, and then shipped to Thailand for final assembly, where it will be matched with zippers from a Japanese company and, finally, delivered to geographically dispersed retailers in quantities and time frames specified well in advance."6 The value web is composed of componentized partners, any number of which can be assembled and coordinated to meet a customer's demand.

It is far from a traditional value chain firm: To build that would require an investment of billions of dollars and a massive organization. Instead, Li & Fung builds size by weaving a services web that spans the globe without having to maintain global points of physical presence. Nonetheless, they play an integral coordination role in processes that produce billions in manufacturing and retail revenues, and that is indispensable to all parties in the value web.

The structure of Li & Fung reflects its role in its web. As John Hagel goes on to describe, "The company has pursued a leveraged growth strategy. It reorganized the company, moving away from an earlier structure built around geography, to a new structure led by small, customer-centric divisions." It componentized its business.

The new organization enables and encourages "lead entrepreneurs" to focus the business on adding value for the customer. "Rather than trying to build or acquire all the specialized processing and transport facilities required to service these customers, Li & Fung focuses on developing deep understanding of the specialized capabilities of existing businesses operating around the world.... When Li & Fung adds a processing facility to its web, it does not view the relationship as a short-term commercial one. It strives to become an important source of business for that facility over the long term, averaging about 30 to 70 percent of its production.... [it] relies on economic incentives rather than detailed contracts or operating agreements to gain access to a highly diverse array of assets around the world."

Nike also orchestrates value webs in order to add value to its own products, but the difference is that unlike Nike, Cisco, and similar companies, Li & Fung does not make any products of its own. Thus, it can offer its relationship and coordination services to any product manufacturer and vendor without being concerned about conflicts of control. This is not a better approach than Nike's, however, just a different way of producing aggressive growth.

Li & Fung doubled its revenues between 1996 and 2000, and its return on invested capital averaged over 30 percent, a huge figure in this low-margin, low-return industry. This last metric is core to its economic efficiency. The 30-percent return comes from its using so little capital; its fixed assets are under 5 percent of revenues. One of the most distinctive advantages of the component-based firm that operates via on demand relationships is an edge in capital efficiency. Studies of supply chain management and logistics show that the top-10 percent of componentized performers in any industry use half the working capital per unit of revenue when compared to the average for their industry. Supply chain management is the earliest and most sustained move to On Demand Business via componentization of all major business functions. Procurement, manufacturing, distribution, and freight are also now accomplished more and more via multi-party value webs. One industry commentator has suggested that in the consumer electronics field, it's no longer Company A competing with Company B, but rather Supply Chain Y competing with Supply Chain Z.

Li & Fung continues to grow. Its revenues increased by 13 percent in 2002, and its net profits grew by 38 percent, while inventories dropped a further 10 percent. In 2003, Li & Fung saw a 26 percent revenue and 22 percent profit increase.

Li & Fung has woven a value web that spans a larger and larger space, and every player gains from being part of this web. Here are examples of the value-added options that Li & Fung creates for itself, its customers, and its many partners:

- "A single factory is relatively small and doesn't have much buying power; that is, it is too small to demand faster deliveries from its suppliers. We come in and look at the entire supply chain." Li & Fung then ensures that the small factory has the resources necessary so that the customer receives the product as promised.

- Li & Fung's centrality in its web means that it can optimize overall costs across the web by increasing individual units' costs. Companies operating in the web try to minimize their own costs in handling shipments, which can lead to overall inefficiencies. In a typical manufacturing scenario, 10 factories will ship full containers of product to 10 distribution centers that send these on to a consolidator. The consolidator then unpacks and repacks them. Li & Fung instead takes on the coordination responsibility and arranges for individual containers to move from one factory to another and then ships it direct to the customer's distribution center, bypassing the intermediaries. The individual shipping costs are higher but the total systems cost is lower.

- "If we don't own factories, how can we say we are in manufacturing? Because, of the fifteen steps in the value manufacturing chain, we probably do ten." "Do" is somewhat misleading in this context, however; Li & Fung's value web partners execute; the company coordinates.

- "As a pure intermediary, our margins were squeezed. But as the number of supply chain options expands, we add value for our customers by using information and relationships to manage the network. We help companies navigate through the world of expanded choice."

- "At one level, Li & Fung is an information node, flipping information between our 350 customers and 7,500 suppliers. We manage that all today with a lot of phone calls and faxes and on-site visits. Soon we will have a sophisticated information system with very open architecture to accommodate different protocols from suppliers and from customers...."7

Hong Kong, where Li & Fung is headquartered, has around 300,000 small- and medium-sized companies. Forty percent of these are transnational. Hong Kong operates around 50,000 factories in southern China, employing 5 million workers. "Hong Kong is producing a new breed of company. I don't think there will be many the size of General Motors or AT&T. But there will be lots of focused companies that will break into the Fortune 1000."8

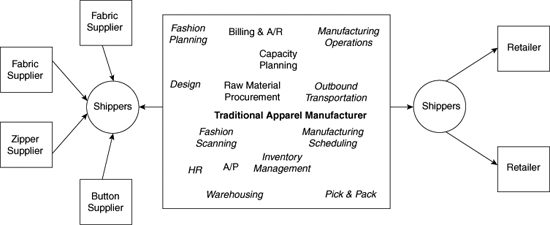

Figures 3.1 and 3.2 illustrate the dramatic impact of the apparel manufacturing value web. Figure 3.1 diagrams the traditional value chain where a manufacturer carries out all the functions contained in the central rectangle, including design, fashion planning, manufacturing operations, warehousing, and billing. As in the standard value chain, to the left are suppliers who provide raw materials via shippers, and to the right are retailers who buy the apparel maker's goods.

Figure 3.1 The traditional apparel value chain.

Figure 3.2 Li & Fung's componentized value web.

The chain is highly disjointed. For instance, the apparel company faces many risks in fashion scanning, planning, and design. They track and assess trends, and while they confer with many experts and customers, they have to make the judgments on what goods to produce in what style and what volume. The retailer similarly has to commit to large orders in advance. This is a hard formula to get right and explains the high percentage of fashion goods that are disposed through cheap outlets or "bargain tables" in stores.

Figure 3.2 captures the componentized value web of a company like Li & Fung. It is the pattern for value webs in consumer electronics, furnishings, and many other ecosystems. Instead of being a chain, with the links wide apart, these players operate as a hub. They coordinate rather than control based on retailers' demands and supplier and manufacturer capabilities and capacities.

In the traditional chain, manufacturing, scheduling, and operations occur inside the firm, and scheduling is itself driven by the manufacturer's forecasts of demand. In the value web, manufacturing scheduling is a Li & Fung component applied across many factories, with Li & Fung the overall coordinator. Now, fashion tracking, planning, and design have been pushed out to where they should be: the retailer who is closest to the end customer. Retailer demand and experience drives manufacturing.

In Chapter 5, "Integrate Your Business Components End to End," we explain how a value web expands the firm's growth space by helping other companies innovate with their own componentization using the platform provided by the web hub operator. We want to emphasize the componentization achieved by Li & Fung; the later TAL example highlights how components can be synchronized to expand the firm's growth space and growth rate.

Componentization is not the rearrangement of building blocks but the basis for configuring the business for growth. In Figure 3.2, the internal operations of Li & Fung are marked by new components such as customer relationship management, which has become the base for its global organizational structure. Because the coordination and planning functions have been componentized, the old sales force and industry marketing groups are now tightly focused on targeted customer relationships; sales and marketing are now an organizational component that interfaces with the planning components. From the perspective of the planning groups, the factories and suppliers are components with coordination handled through a heavy flow of messages. The shippers are now part of a platform that permits the consolidation of containers and other process innovation.

It all begins with componentization. Without that, the shift from the traditional value chain to value webs just cannot be achieved.

Why Componentize?

If the only answer to the question "why componentize?" was that "you have no choice," this would be a short, depressing book. All that companies could then see on the horizon is outsourced everything, layoffs, price cuts, restructuring charges, and being gobbled up by larger companies.

A few observations suggest otherwise:

- Companies that have sustained growth and profits are consistently in commodity industries with componentized businesses: Wal-Mart in retailing, Dell in computers, and Southwest in airlines.

- Speeches about General Electric's and eBay's growth strategies given by their CEOs are so similar in tone and focus that they are basically interchangeable, and it can be hard to discern which speaker is which. Their constant themes are standardization and centralization, which sound like the bureaucratic opposite of the innovation that they see enabling their firms.

- Global sourcing has taken on a new scale, and moved quickly from low-level manufacturing assembly work to the very core of developed countries' innovation base—its information technology talents, research and development, and design creativity. Does everyone see it as a way just to cut costs, or are some seeing much more?

- It makes so much sense for BMW, the leader in the high end of the car "manufacturing" market, to contract out the production of its top-of-the-line X3 series sports utility vehicle to a specialist firm, Magna, making it a non-BMW BMW.

The answer to the question "Why componentize?" is "because it helps us grow."

Components with Standardized Interfaces

It is hard to overstate the impact of standard interfaces in helping move from complexity to simplicity. Here are examples of business services that many of us access on an everyday basis via a standard interface and use in our business or personal life that provide simplicity, even though they are extraordinarily complex. The interface hides the complexity:

- Shipping—If you are a small business, FedEx is a service that you use on a dial-up or log on and "forget-about-it" basis. From your perspective, FedEx is a component in your value web. You need know nothing about how FedEx works, and you never have to phone around or track down people. Your business is stronger because you can access any FedEx business services such as picking up returned goods, or managing your just-in-time inventory. Because FedEx has componentized its business, it can offer a wider array of services, and even change its internal processes and systems without affecting you.

You don't have to know what goes on inside and don't care, because it just works. By contrast, the typical health insurer cannot be treated as a component, by doctors, patients, hospitals, or government health and social services agencies. Little is standardized and multiple forms, formats, administration, and overhead impede organizational agility. It is a muddle of individual hands-offs and uncoordinated independent activities. - Shopping—Buying a shirt at JC Penney or ordering a pair of custom-made jeans from Lands' End have one surprising element in common: Neither company has anything to do with the product. They take the order acting purely as the interface. TAL in Hong Kong does forecasting based on point of sales data, coordinates the firms whose individual business components—dyeing, cutting, sewing, packing, and shipping—create the final product and deliver the item of clothing to each store or direct to the customer. JC Penney has cut its warehouse and in-store inventory as a result. The retailers simply treat TAL's services as a component in their own business.

These services are simple to use because they are componentized with clean interfaces. All you do is call, log on, plug in, or pick up. It's easy, consistent, and reliable. As a customer, why accept anything else?

In conclusion, there are three very good reasons to componentize your business: because you have no choice in the long run, because you gain the growth advantage, and because it makes life easier for your customers.

Summary

Businesses are increasingly defined by their ability to produce and integrate with business components. These business components are disparate elements that, when stitched together intelligently, produce industry-leading value webs that redefine the entire market segment. Componentization produces growth opportunities, but it also creates problems and challenges for many firms, challenges that some will not be able to overcome. The simplistic approach to components is outsourcing, but companies don't become market leaders through outsourcing; they do it through building value webs and offering innovative, unique, and high-value components to the web along with coordination capabilities.