Challenges Faced by Knowledge Workers in the Global Economy

Until recently, the business-critical value of knowledge management (KM) investment was all but assumed, and experts on the subject all realized that their assumptions were wrong. Many predicted, and are still predicting, that KM and its derived career paths are doomed to extinction. In fact, more than ten years ago, during the spring of 2001, CIO magazine commented that KM systems (KMS) didn’t work, in particular due to the fact that no one in the organization would use or support such systems, beginning with upper management. And they were right!

Fast forward to the financial meltdown of 2008 and we realized that very few companies have escaped the impact of the past year’s economic woes. Even those organizations that have not been forced to implement redundancy programs have had to implement widespread budgetary cuts, some asking employees to take sabbaticals or part-time work, until economic conditions improve. With resources tight, and internal departments in a state of flux, the case for KM has become even trickier. While KM is normally seen as a support service, KM teams may have been among the first to have been culled in recessionary conditions.

But interesting enough, through my consulting practices, those companies that view KM as essential, and central, to business profitability have been more reluctant to make cuts, PPL Montana is a good example of it, as they continue to invest in its people and knowledge capital, and are being very successful at it. In my experience, only a few KM teams have passed through the recession completely unscathed trough.

The theory that a KMS was only as good as its information technology has been nearly unquestionable. But I believe the thinking behind this theory is murky. For the past five years or so, the resounding message from all sectors—professional services firms, corporates and public sector alike—is that KM is now about doing more with less.

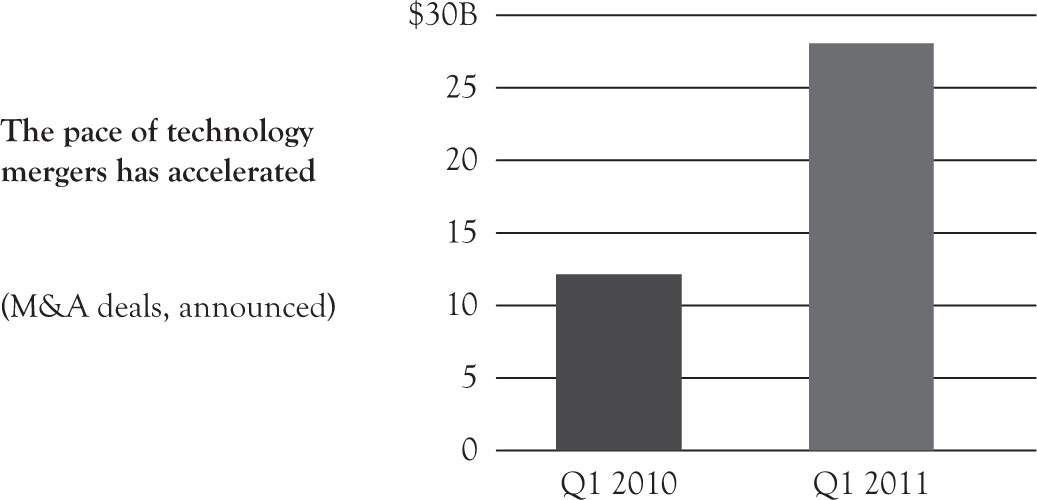

The problem is that, as companies focus on building knowledge database repositories and data mining techniques, the majority of them ignore their people and their cultural issues. I believe the massive investments in KM projects in the first decade of the 21st century were thought to underlie the historical globalization, merger and acquisition (M&A) activities across the globe that characterized the 90s. Technology is again becoming one of the most active M&A sector during the past couple of years, much as in the late 1990s, as Figure 1.1 shows.1 Consequently, the need for information sharing among disparate systems and knowledge base ones were too great, even though the objective evidence for such a claim is controversial at best, but nevertheless, KM has had a free ride for at least the last three or four years.

Figure 1.1. Technology is the most active M&A sector since 2010.

Source: Ernst & Young’s Global technology M&A update: January–March 2012 report.

The Role of KM

The question we might ask in attempting to define the role of KM is not simple. Was KM the hot topic of yesterday? Is business sustainability now the hot topic of today? Are they different, or is sustainability an expansion of the KM concept?

The American Productivity & Quality Center (APQC) describes KM as a mindset that extends beyond the flow of traditional business process. It focuses on the dissemination of information, engagement of key resources, and ultimately the adoption rate of best practices across the entire value chain. I believe KM and sustainability concepts to be intricately aligned, a critical aspect of business sustainability.

But, the ability to define, implement and manage future business opportunities will depend largely on the availability and quality of critical business information such as:

•Mission: What are we trying to accomplish?

•Competition: How do we gain a competitive edge?

•Performance: How do we deliver the results?

•Change: How do we cope with change?

The bottom line is that the era of KM accountability has come, and corporate KM systems will be judged on the basis of their ability to deliver quantifiable competitive advantage, capable of making your business smarter, faster, and more profitable. In the process, the need to sell the KM concept to employees shouldn’t be underestimated. In a fast-paced global economy, knowledge workers should strive to promote an environment where an individual’s knowledge is valued and rewarded, establishing a culture that recognizes tacit knowledge and encourages everyone to share it. How we go about it is the challenge.

The old practice of employees being asked to surrender their knowledge, and experience the very traits that makes them valuable as individuals must change. Knowledge cannot be captured; if so, it dies. Thus, motivating employees to contribute to KM activities through implementation of incentive programs is frequently ineffective. Often, employees tend to participate in such programs solely to earn incentives, without regard to the quality or relevance of the information they contribute.

The main challenge here is that KM is overwhelmingly a cultural undertaking. Before setting the course for a KM project and deciding on KM technologies, you will have to know what kinds of knowledge your organization’s employees need to share and what techniques and practices should be implemented to get them to share. Thus, you will need a knowledge strategy that reflects and serves as business’ goals and attributes. A dispersed, global organization, for example, is probably not well served by a highly centralized knowledge strategy.

To be successful, knowledge workers must be able to implement a very transparent KM activity, one that is focused on simplicity, common sense, and at no time, imposed. Whatever is imposed will always be opposed, which immediately compromises the value and integrity of the knowledge being gathered or shared. Ideally, every employee should desire participation in KM efforts. It should come from within, and its participation should be its own reward. After all, the goal of such initiatives should be to make life easier for employees, therefore positively affecting the bottom line. Otherwise, such effort has failed.

No doubt KM can revolutionize corporation’s capital knowledge and sharing. But it won’t be easy, and is not likely to be cheap, as the challenges are many, and breaking down user’s resistance is one of the major challenges knowledge workers face. You just don’t get moving just by buying and installing one of the many KM applications already available on the market. One must have a deeper understanding of the reason, the context and the business challenges being addressed. Therefore, in general knowledge workers are responsible for:

•Strategic issues related to learning, business intelligence, customer relationships, intellectual assets, and agility.

•Influencing, building and changing organizational culture, practices and policies to enable greater innovation, knowledge sharing and creativity.

•Introducing advanced practices to improve knowledge creation and sharing, such as, tools for building a corporate memory, enabling virtual forums, stewarding communities of practice, assisting with informal learning.

Knowledge managers are also expected to engage and mentor executives in the finer points of KM—creating open space, building trust, showing a tolerance for learning via errors, helping with hiring qualities that promote knowledge flows. Depending on circumstances, they may be involved with knowledge audits and mapping, development of taxonomic policy, decisions on software procurement and adoption and will be expected to lead the firm in working with tacit knowledge assets.

There are many more roles and competencies, but I would recommend that you to spend quality time planning the KM strategy, and be forewarned that the initiative may be expensive, not only in terms of capital investments but also in terms of human resource and organizational investments. With that in mind, you will be able to better plan for it. You should begin with the challenges discussed here. Then, you should focus on the many strategies outlined throughout this book, which affect, not only IT support, but also cultural and business issues, and ultimately the role of the knowledge worker as catalyst and flagship of the whole process.

Implementing KM

The ultimate goal of a knowledge worker should be to bridge the gap between a corporation’s know-how and its how-to. Even if a KM implementation is successful from the technical, usability, knowledge aggregation and retrieval view, empowering the organization to transform its know-how into how-to is still virtually a utopian task. But I’m a believer that the definition of success equals vision in action. Seeking business success, several companies undertake tremendous reengineering cycles and hire expensive consultants to tell them what they often already know, and have known for years, after reports and more reports generated by a number of management and business consulting firms.

You might have a clear vision of your KM project goals, but if you don’t have a clear action plan in place, one that can be measured using reliable metrics, you just won’t succeed. By the same token, you may have a clear action plan, one that very likely has been outlined, developed, and recommended in-house, or by outside consultants, but if you don’t have a clear vision of where you are going, the results you want to achieve, you just won’t get there either.

Don’t underestimate the complexity of KM implementations. If you look at enterprise resource planning (ERP) and customer relationship management (CRM) solutions you can have some idea. But very few ERP implementations have been fully successful; most of them are still under the implementation phase, being clogged up with CRM solutions, or already undergoing some level of business process rethinking. The same goes for CRM. According to Mendoza, Marius, Pérez, & Grimán (2007) survey results, the main causes of CRM project failures have to do with organizational change (29%), company policies/inertia (22%), little understanding of CRM (20%) and poor CRM skills (6%). Mind you, CRM success results are much more tangible to measure than KM ones!

What those surveys underline is an increasing skepticism about intelligent systems. Knowledge workers must be able to avoid, if not eliminate, them. To get 100 percent satisfaction in KM implementations is not only very expensive, but near to impossible. It’s not enough to install a KM system. You need to convince your people to use it, starting with upper management.

In addition, immediate results are near nonexistent, until users are able to feed the system with all their best practices, explicit knowledge, and whatever knowledge they believe can earn them the announced motivational perk. Of course, you can always mention the success of the KM system used by British Petroleum sharing knowledge through its virtual team network.2 The aim of that system was to allow people to work cooperatively and share knowledge quickly and easily regardless of time, distance, and organizational boundaries. The network is a rapidly growing system of sophisticated personal computers equipped so that users can work together as if they were in the same room and can easily tap the company’s rich database of information. The PCs boast videoconferencing capability, electronic blackboards, scanners, faxes, and groupware. Amazingly enough, today’s knowledge worker’s challenges are much broader in scope, as well as influential. The following are the most important ones.

Technology-Driven KM Challenges

KM and learning are both evolving practices enhancing individual‘s learning and understanding through provision of information. KMS are normally characterized as technologies to provide and access information. However, the pedagogical approaches used are more important than the procedural features of the technology. Thus, one of the main challenges of knowledge technologies relates to the pedagogical approach in implementing and using such systems. It is important to adopt a knowledge-based pedagogical (KBP) framework that highlights the involvement of KM across the organizations. There are still many unanswered questions concerning the part that knowledge plays in decision-making and key challenges to integrate customer’s value, evidence and choice into a KM system. This, I believe, is due to lack of pedagogical practices on assessing the value of knowledge, comprehension and learning applications.

A mistake several organizations continue to make with KM initiatives is to think of it as a technology-based concept. There are no all-inclusive KM solutions and any software or system vendor touting such concept is either deceived or grossly misinformed. To implement solely technology-based systems such as electronic messaging, Web portals, centralized databases, or any other collaborative tool, and think you have implemented a KM program is not only naïve, but also a waste of time and money.

Of course, technology is a major KM enabler, but it is not the end, and not even the starting point of a KM implementation. A sound KM program should always start with two indispensable and cheap tools: pencil and paper. The knowledge worker’s challenge here is to plan, plan and plan. KM decisions must be based on strategies defined by the acronym W3H (who, what, why, and how), or the people, the knowledge, the business objectives, and the technology, respectively. The technology of choice should only come later.

Another challenge that tends to be technology driven is knowledge flow, which is often a stumbling block in most KM programs, and the big mistake knowledge worker’s make is to look at technology as the main solution to support the flow of knowledge. Knowledge flow is a much more complex issue, which involves the process of creation and dissemination of new knowledge, as well as human motivation, personal and social construction of knowledge, and virtualization of organizations and communities. I believe knowledge flow is only sustained by the human desire to make sense—common sense that is—of issues that transcend the everyday business scope, but it is very much present in every moment of a professional’s life, no matter what his or her trades are.

Every day, as we assimilate, store and disseminate knowledge, organized or not, we are trying to make sense of issues that relate to our interests, passions, lives, work and even family. No technology system can capture such unstructured and tacit knowledge. Trying to do so, instead of supporting its flow, stops it. The situation becomes even more complex when we consider the cultural aspects so present in multinational organizations, especially those that have gone through a merger with foreign companies.

Common sense should also apply to business processes. Most of our business reasoning and purposes are built around a process of justifications for what we would like to do in order to satisfy a business requirement (or is it in order to satisfy ourselves?). In this process, knowledge workers should be aware of tacit knowledge present by virtue of previous experiences in every employee, as well as their studies, thinking, cultural background, while they attempt to verbalize it in form of their responses. Technology alone won’t help you in this process.

Addressing the Challenges

KM is without a doubt an oxymoron that explains the difficulty in reconciling the soft issues around it, such as innovation and creativity, with hard issues, such as performance benchmarks’ measurement and assessment. There is a diametrically opposed assumption about the definition and nature between knowledge and management, but for a knowledge worker, management and control are not synonymous, as it would be for a CTO or a CIO.

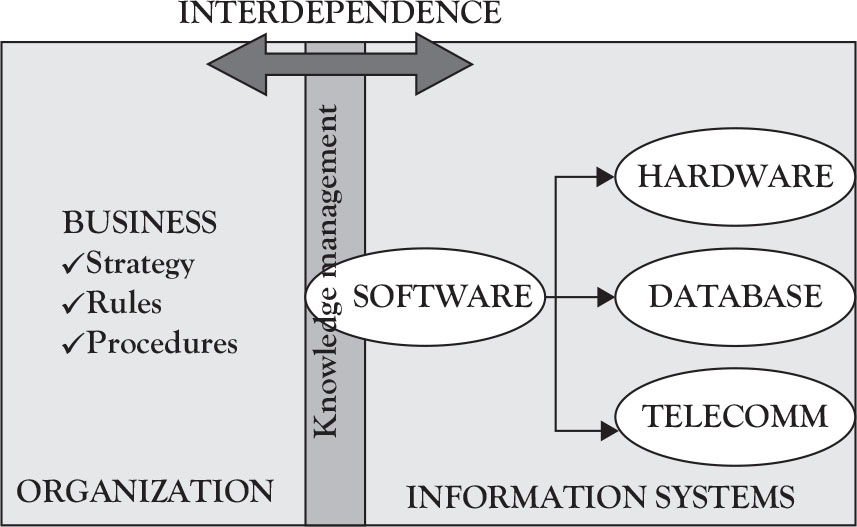

To cope with the challenges knowledge workers face in organization is not an easy task. Today’s knowledge worker’s roles are still not well defined, many times confused with those of a CTO with business and information systems skills, or from a different angle, as of a CIO with business and information technology expertise. Much of it is because the role of a knowledge worker in today’s organizations falls into a demilitarized zone between the organization and information systems, as depicted in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2. KM is the only discipline with a real chance to manage the systems interdependencies between the organization and information systems.

As a result of this super information overflow, KM initiatives are often disappointing, as there is a lack of user uptake and a failure to integrate KM into everyday working practices. However, such outcome can be avoided, and this is what this whole book is all about. Make sure to tighten your KM efforts to high-priority business objective—just as you wouldn’t fish in a pond with a bazooka, don’t invest in KM just for KM’s sake. To be successful, knowledge and learning goals must be articulated at the same level of an organization’s business objectives. This is the only way learning and knowledge sharing can truly become culturally embedded in the organization. If you want KM to succeed, you must integrate your people with the organization’s business process and the technology you will be using—KM should always be a work-in-progress, never a finite project. Its never-ending integrated process should always be the implementation of a competitive strategy, which appreciates that learning and sharing knowledge are equally important.

Implementing KM is not as easy as we would like it to be. Really, you only have one shot, and if this fails, you may find that the concept has become irrecoverably tarnished. Therefore, before even thinking about the implementation of KM you must devise a plan based on lessons from successful (and not so successful!) implementations in other organizations, and adapted to your own corporate needs.

A sound KM implementation plan should be based on:

•The results of assessment and benchmarking (if available);

•A KM strategy (if available);

•The proposed and agreed KM framework (if available);

•A communications plan (if available);

•A staged, change management approach;

•A full analysis of the risks to KM delivery.

In addition, when considering a KM implementation, make sure to have a knowledge strategy aligned with your organization’s business strategy way before considering any technology tool. And make sure the strategy defines all key KM processes:

•Creation of new knowledge

•Identification of knowledge

•Capturing of knowledge

•Knowledge mapping

•Knowledge sharing, application and reuse

•Protection and security of knowledge assets.

Chapter Summary

In this chapter we discussed the challenges faced by knowledge workers in the global economy. We addressed the new roles KM must embrace to address the challenges of a heterogeneous global business environment, as well as the factors involved in the implementation of KM at organizations, particularly the technology driven ones.