In 2002, US Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld said the following during a briefing:

… there are known knowns; there are things that we know that we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

This is partly true of threats, but very true of vulnerabilities.

Threats, as we see in the glossary in Appendix I, are the ‘potential cause of an unwanted incident, which can result in harm to a system or organisation’. Threats are slightly different from hazards, which may still cause an unwanted incident resulting in harm to an information asset, but whereas threats are generally man-made and deliberate, hazards are more usually accidental or naturally occurring.

Vulnerabilities are defined as ‘the intrinsic properties of something resulting in susceptibility to a risk source that can lead to an event with a consequence’. Vulnerabilities are weaknesses either in information assets themselves, or in the infrastructure that supports the information assets, including the people who have ownership or responsibility for them.

CONDUCTING THREAT ASSESSMENTS

Some experts believe that the threat and vulnerability assessments should be carried out ahead of the impact assessments; others disagree and opt for the reverse arrangement.

I believe that, in practice, either method will suffice as long as the information assets have been clearly identified, but that it can be extremely helpful if the threat and vulnerability assessments can be performed at the same time as impact assessments, since many of the threats and vulnerabilities will be apparent to the information asset owners. Further threat and vulnerability assessments can be conducted at a later time with other knowledgeable staff, especially with information security specialists.

For every threat identified, there may well also be some data on the frequency of historical events where the threat has either been known to have been used or to have succeeded.

It is also worthwhile remembering that a threat can only cause an impact on an information asset if the asset contains a vulnerability for the threat to exploit.

To begin with, it may well be worth running a brainstorming session to identify possible threats. In the first pass through, as with normal brainstorming rules, no suggestion should be discounted, no matter how bizarre it might seem, since sometimes those ideas that seem crazy at first glance turn out to be viable threats. The weeding out of the very unlikely threats can come at a later stage when the likelihood assessments are carried out.

It is worthwhile remembering, however, that even the most thorough threat assessment might not identify all the threats and hazards that the organisation faces, and also that new ones may emerge with time, so, as with all other aspects of an information risk management programme, this should be an ongoing activity.

Following the first pass through a brainstorming session, it may also be beneficial when conducting both threat and vulnerability assessments to use a mind map, so that all threats, hazards and vulnerabilities can be grouped, as shown in Figure 5.1.

The output of the threat assessment will include threats and hazards from a number of different sources including, but not limited to:

- malicious intrusion or hacking;

- environmental threats and hazards;

- errors and failures;

- social engineering;

- misuse and abuse;

- physical threats;

- malware.

These threats and hazards are described briefly below, and in greater detail in Appendix B.

Malicious intrusion or hacking

Hacking is a generic term applied to many forms of unpleasant behaviour, although it began as a description of what people did in order to find out how computers worked and how to improve their performance. Hacking almost invariably results in a breach of confidentiality, integrity or availability as hackers use software tools to intercept and decrypt legitimate information, and either steal it or change it. Occasionally, hacking is used to deliver so-called ‘denial of service’ attacks, designed to prevent legitimate access to systems, often to make a political point.

Since the introduction of the Computer Misuse Act in 1990, hacking is now treated as a crime, since it invariably involves accessing a computer without the owner’s permission to do so.

It is becoming more and more common to hear news stories about hackers who steal large quantities of information, such as user identifiers and passwords, and sell this information on – usually to criminal gangs – for use in wider fraud.

On 22 September 2016, Yahoo! Inc. announced that a massive data breach of its service had taken place – with roughly 500 million user accounts’ passwords, along with other sensitive information, stolen – claiming that the breach was perpetrated by a ‘state actor’. Interestingly, details of the attack were revealed just as Yahoo! was trying to negotiate a buy-out by Verizon – the news would certainly have affected the company’s share value.

Hacking includes:

- denial of service (DoS) attacks;

- unauthorised access;

- unauthorised network scanning;

- interception;

- session hijacking;

- website modification;

- software modification;

- data modification;

- decryption;

- credential theft.

Environmental threats and hazards

These types of threat are almost always concerned with availability, since they affect the environment in which a system resides. Those threats that occur as a result of natural events – for example, severe weather – are often referred to as hazards in order to distinguish their origin from those of malicious threats. Many of these hazards affect a wide geographic area, and can cause serious disruption to multiple organisations rather than to a specific organisation or system.

Examples of environmental threats include:

- natural hazards such as severe storms and flooding;

- accidental and malicious physical damage;

- fire;

- communications jamming or interference;

- communications failures;

- power failures;

- pandemics.

Errors and failures

Errors fall neatly into two categories: those made by users and technical staff, and those things that simply fail. Neither form is generally regarded as being malevolent, even though some user and technical errors are caused by lack of attention or poor training. Despite the view of many technicians that both hardware and software are designed to cause them grief, there is no evidence to suggest that this is actually the case.

Examples of errors and failures include:

- software failures;

- software interdependencies;

- system overloads;

- hardware failures;

- user errors;

- technical staff errors;

- internal and external software errors;

- change failures.

Social engineering

Social engineering is a technique used by hackers and other ne’er-do-wells to acquire information, generally about access to systems so that their hacking activities are simplified. Social engineering comes in several forms – not only the traditional approach where a hacker attempts to engage with a user by conversation (usually over the telephone or by email), but also by disguising malware as legitimate software and web links and by copying the style-naming conventions and language of a target organisation. For example, they may send a user an email that appears to originate from their bank, but in which embedded web links take the user to the hacker’s own website.

Examples of social engineering threats include:

- spoofing, masquerading or impersonation;

- phishing;

- spam;

- disclosure.

Misuse and abuse

Whereas hacking is usually deemed to originate from outside an organisation, misuse normally originates from within. The net result may well be the same for either approach, but in the case of misuse, the internal user or technician has the added advantage of already being on the inside of the organisation’s firewall and security systems, may have access to the required passwords and, critically, may also have elevated access privileges. For this reason, the threat from internal attackers potentially presents a significantly greater level of likelihood of success than that of an external attacker.

Examples of misuse threats include:

- modification (invariably elevation) of privileges;

- unauthorised system activity;

- software and business information theft.

Physical threats

Physical threats may also be easily undertaken by employees – many will have access to systems and equipment that they can readily remove from the organisation’s premises without the fear of discovery, whereas an external attacker would have to pass through the organisation’s layers of physical security in order to do so.

There is a salutatory (possibly apocryphal) anecdote from the building trade that tells of the employee who pushed a wheelbarrow covered with a tarpaulin home at the end of every day’s work. Every evening the site foreman checked beneath the tarpaulin to find there was nothing there and let the employee go on his way. Eventually it was discovered that the man was stealing wheelbarrows and tarpaulins.

Physical threats include:

- unauthorised access;

- theft of computers and portable devices;

- theft of authentication devices.

Malware

The term ‘malware’ is used to refer to malicious software that can be used to attack an information system. Examples of malware include software entities that result in the collection of, damage to or removal of information. Such software is almost always concealed from the user, often self-replicating (attaching itself to an executable program) and can spread to other systems when the user unwittingly activates it.

Some malware goes to great lengths to conceal its existence, appearing to the user as legitimate software. Its purpose, however, is usually sinister in that it may collect, damage or remove information when the user activates what they believe is a legitimate program.

- viruses;

- worms;

- Trojan horses;

- rootkits;

- spyware;

- active content;

- botnet clients;

- ransomware.

Who should be involved in a threat assessment?

As with the impact assessments covered in the previous chapter, the information asset owners should be the first port of call for this activity, since they may well already be aware of many of the threats their information assets face. However, other parts of the organisation will be able to provide input on this, such as the IT department, human resources and the organisation’s information security team. A typical threat assessment form might look something like that shown in Figure 5.2.

Additionally, there are comprehensive examples of threat types to be found in Appendix C of ISO/IEC 27005:2018, including suggestions as to the origin of threats – accidental, deliberate and environmental – as well as the possible motivations and consequences of threats resulting from various types of threat source.

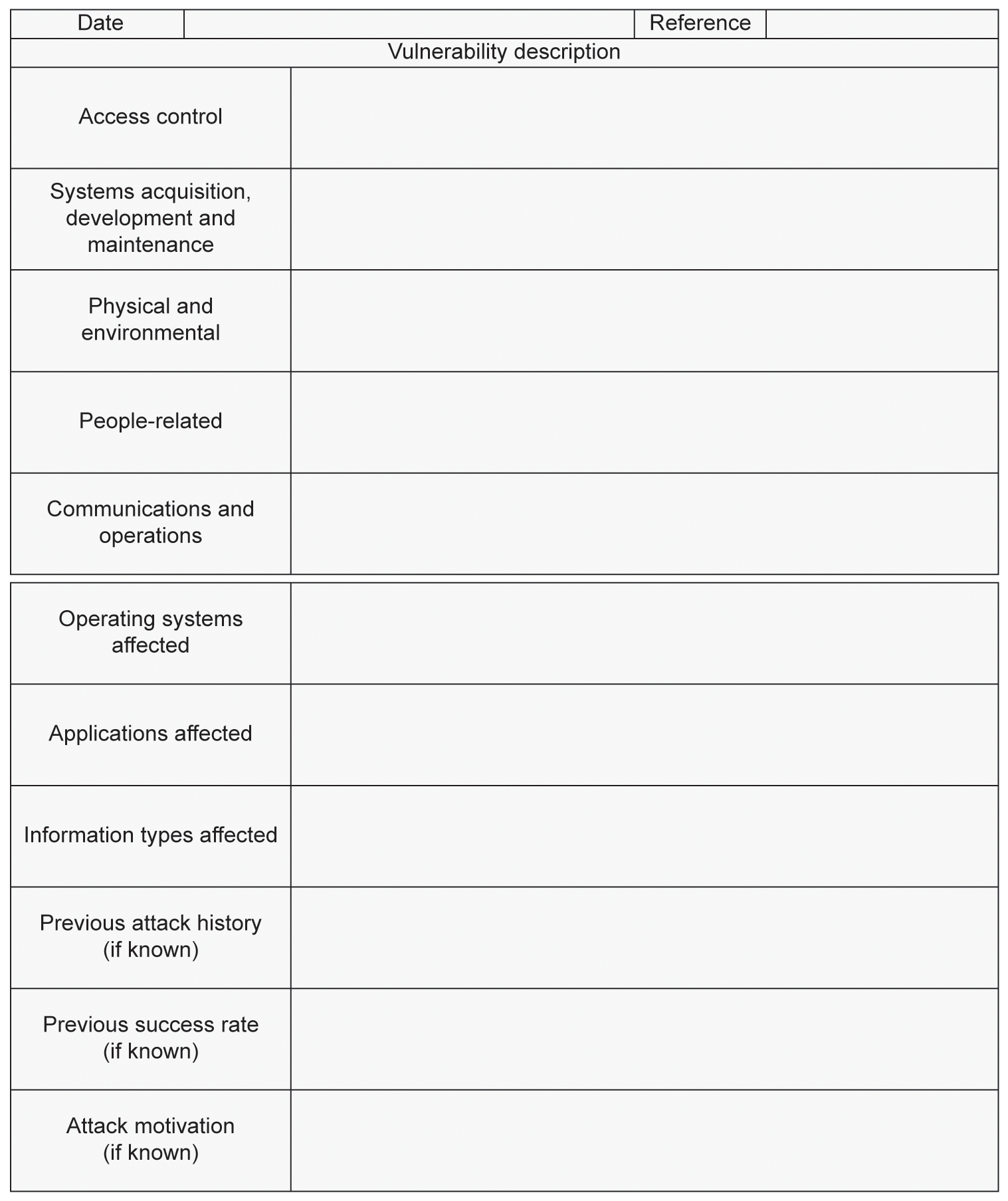

CONDUCTING VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENTS

Vulnerabilities are weaknesses either in information assets or in the infrastructure that underpins them, while threats exploit vulnerabilities in order to achieve an impact.

The output of the vulnerability assessment will include such vulnerabilities as:

- access control failures;

- systems acquisition, development and maintenance procedures;

- physical and environmental failures;

- communications and operations management failures;

- people- and process-related security failures.

However, as already stated, vulnerabilities alone cannot cause an impact on an information asset, as an impact requires the presence of a threat to exploit the vulnerability.

For every vulnerability identified, there may well also be some additional data on whether the vulnerability has been known to have been exploited, whether such exploits have succeeded and whether there might be known controls that are already in place in partial mitigation.

As with threat assessments, it may well be worth running a brainstorming session to identify possible vulnerabilities, and in the first pass through, as with normal brainstorming rules, no suggestion should be discounted no matter how bizarre it might seem, since sometimes those ideas that seem crazy at first glance turn out to be viable vulnerabilities. The weeding out of the very unlikely vulnerabilities can come at a later stage when the likelihood assessments are carried out.

It is worthwhile remembering, however, that even the most thorough vulnerability assessment might not identify all the vulnerabilities that affect the organisation’s information assets, and also that new ones may emerge with time, so as with all other aspects of an information risk management programme, this should be an ongoing activity.

Following the first pass through a brainstorming session, it may also be beneficial when conducting vulnerability assessments to use a mind map, so that all vulnerabilities can be grouped, as shown in Figure 5.3.

Typical vulnerabilities are described briefly below, and in greater detail in Appendix C:

- access control failures;

- poor systems acquisition, development and maintenance procedures;

- physical and environmental failures;

- communications and operations management failures;

- people-related security failures.

Access control failures

Access control has two complementary uses – firstly to permit access to resources for authorised persons, and secondly to deny access to those resources to unauthorised persons. Failures in access control are very likely to increase the likelihood of successful attacks against information assets.

If you are able to obtain a copy, Appendix C4 of BS 7799-3:2017 provides a highly comprehensive list of vulnerabilities, together with a brief description of how they might be exploited.

Access control failures include:

- The lack of, or poorly written access control policies.

- Failure to change access rights of users changing roles within the organisation.

- Failure to revoke access rights of users leaving the organisation.

- Inadequate user password management.

- The continued use of default system accounts and passwords.

- The use of passwords embedded in software applications.

- The lack of security of mobile devices.

- The lack of network segregation.

- Failure to impose a clear desk and clear screen policy.

- The use of untested software.

- Failure to restrict the use of system utilities.

Poor systems acquisition, development and maintenance procedures

When acquiring systems hardware and software, developing software and maintaining both, it is vital to ensure that selection or specification is carried out according to a formal set of criteria that include appropriate security features. Unlike access control failures, this type of vulnerability is rarely noticed immediately but can result in serious consequences at a later time.

The root cause of this is often a failure to correctly specify appropriate criteria prior to acquisition or development, and may result either from a lack of forethought or a desire to achieve cost savings.

This type of vulnerability includes:

- The lack of clear functional purchasing specifications.

- The lack of clear functional development specifications.

- Failure to validate data entry.

- The use of untested software.

- The use of unauthorised software.

- The lack of BC and DR planning.

Physical and environmental failures

Physical security is normally highly visible, both to staff and to potential intruders. Very often, the mere presence of robust security is sufficient to deter an intruder, but even so it is important that physical security measures are appropriate and well maintained, and failure to do this increases the organisation’s likelihood of experiencing intrusion of some description.

Environmental vulnerabilities tend to be rather more difficult to address, but are generally relatively easy to identify and can either relate to the location or construction of premises (for example, a data centre built on a flood plain) or to the environmental subsystems that underpin major premises such as large office buildings, factories, warehouses and data centres.

Physical and environmental vulnerabilities include:

- Poor management of access to premises and to areas within them.

- Inadequate physical protection for premises, doors and windows.

- The lack of suitable protection for stored equipment and supplies, and especially waste.

- The use of unsuitable environmental systems, including cooling and humidity control.

- The location of premises in areas prone to flooding.

- The uncontrolled storage of flammable or hazardous materials.

- The location of premises in proximity to flammable or hazardous materials or facilities that process them.

- The lack of standby power supplies.

Communications and operations management failures

Along with access control failures, failures of operations management and communications systems rank high among the vulnerabilities that can be successfully exploited, whether deliberately or accidentally.

Many of these exploits are possible due to process failures – again, either through failure to observe them or failure to have processes in the first place.

Communications and operations management failures include:

- The failure to ensure the appropriate segregation of duties where necessary.

- Inadequate network monitoring and management including intrusion detection.

- The use of unprotected public networks.

- The uncontrolled use of users’ own wireless access points (WAPs).

- Poor protection against malware and failure to keep virus protection software up to date.

- Failure to maintain patching of software.

- Inadequate and untested backup and restore procedures.

- Improper disposal of ‘end of life’ storage media.

- The lack of robust ‘bring your own device’ (BYOD) policies.

- Inadequate change management procedures.

- The lack of audit trails, and non-repudiation of transactions and email messages.

- The lack of segregation of test and production systems.

- The uncontrolled copying of business information.

People-related security failures

The vulnerabilities that are caused by the failures of users and operational staff are almost all related to policies and processes:

- The insufficient or inappropriate security training of technical staff.

- The lack of appropriate security awareness training for users.

- The lack of monitoring mechanisms, including intrusion detection systems.

- The lack of robust policies for the correct and appropriate use of systems, communications, media, social networking and messaging.

- The failure to review users’ access rights whenever they change roles or leave the organisation.

- The lack of a procedure to ensure the return of assets when leaving the organisation.

- Demotivated or disgruntled staff.

- Unsupervised work by third-party organisations or by staff who work outside normal business hours.

Who should be involved in a vulnerability assessment?

As with the threat assessments covered earlier in this chapter, the information asset owners should be the first port of call for this activity, since they may well already be aware of many of the vulnerabilities their information assets possess. However, other parts of the organisation will be able to provide input on this, such as the IT department, human resources and the organisation’s information security team.

Since many of the vulnerabilities identified will be of a technical nature, it is probable that various forms of security testing will identify them, including penetration testing and vulnerability scanning tools.

A typical vulnerability assessment form might look something like that shown in Figure 5.4.

IDENTIFICATION OF EXISTING CONTROLS

Controls are generally designed to treat risks – either by removing or reducing the impact on an asset, or by removing or reducing the likelihood of the threat occurring. However, controls may also be used to monitor processes, ensuring predictability without actually modifying them.

Before we can move on to the next stage of risk assessment, we must identify all existing controls that are in place and also verify that they are working as expected. There are three reasons for doing this:

- Firstly, to ensure that when we conduct the likelihood assessment, we have all the necessary information to do so accurately.

- Secondly, to ensure that when we begin the process of determining the appropriate controls to mitigate the risks we have encountered, we do not attempt to duplicate controls that are already in place, and that they are effective and functioning as expected.

- Thirdly, so that any controls that are not effective or functioning as expected can be reviewed and removed or replaced as necessary.

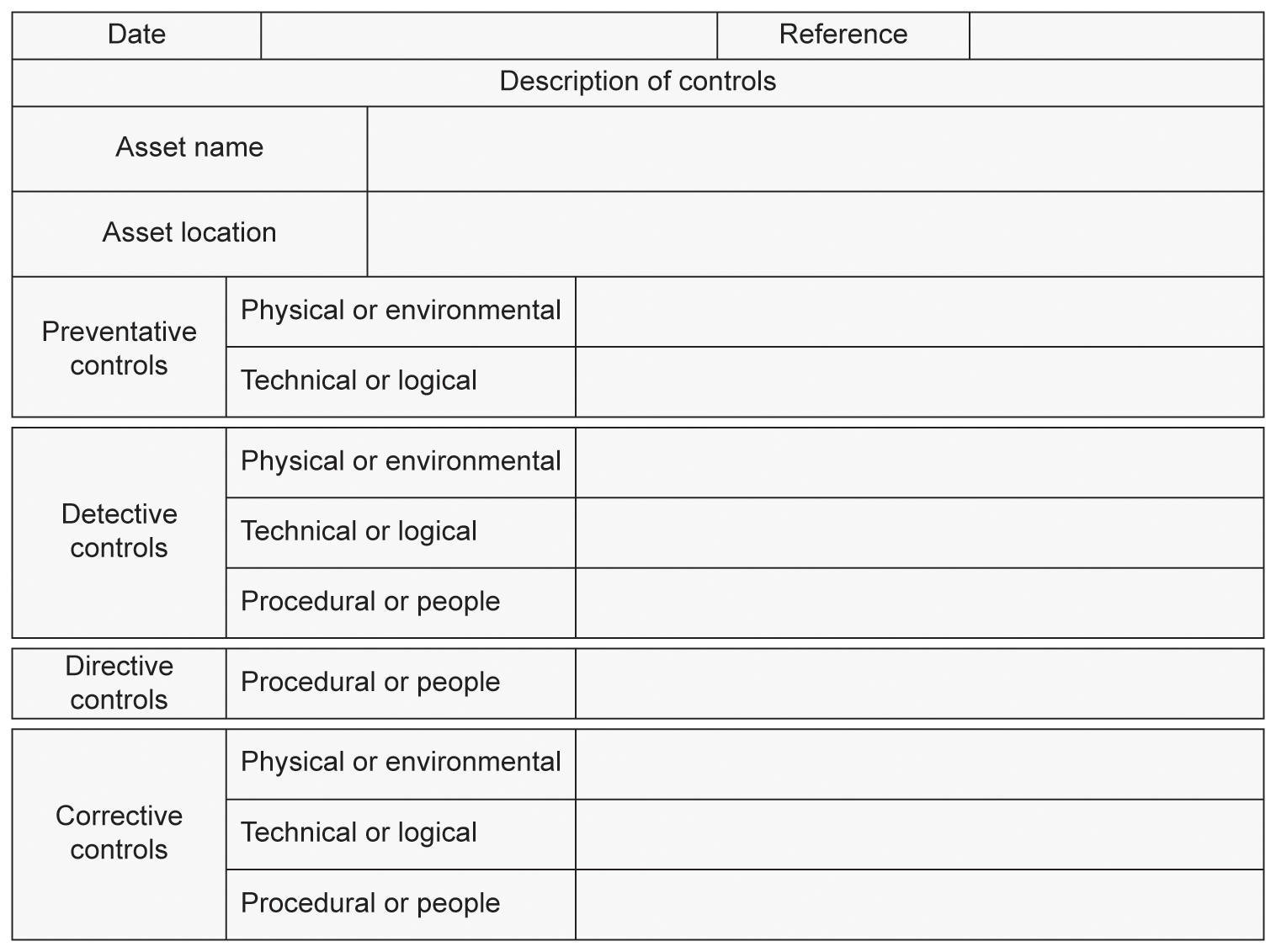

Figure 5.4 Typical vulnerability assessment form

If the organisation has already been through one complete information risk management programme, then the information to complete this activity will be in the risk register. If, however, this is the first time it has been conducted, the identification of existing controls will have to be carried out from scratch.

We deal with controls in much greater detail in Chapter 7, but in order to assist the identification process for this stage of the work, the following should prove useful.

Controls are divided into four strategic, four tactical and three operational types, but not all combinations of these exist, as illustrated in Figure 5.5.

Strategic controls are:

- Avoid or terminate – that is, either cease an activity that incurs risk or do not begin it.

- Transfer or share – that is, spread the risk between the organisation and one or more third parties.

- Reduce or modify – that is, change either the impact or the likelihood in some way.

- Accept or tolerate – when the other options cannot treat the risk, or when there is residual risk remaining after any of the above methods have been used, this is the one choice remaining.

Tactical controls are:

- Detective – that is, being alerted to something happening.

- Preventative – that is, stopping something from happening.

- Directive – that is, putting in place some form of instruction.

- Corrective – that is, altering the state or condition of something.

Operational controls are:

- Physical or environmental – these are usually concerned with the infrastructure that underpins the information assets. Typical examples of physical controls are the use of CCTV to monitor areas within a site, and electronic door locking mechanisms to control access into restricted areas.

- Procedural or people – these are concerned with ensuring that processes and procedures are followed. Typical examples of procedural controls are change control mechanisms to manage additional systems or services, and the segregation of duties that could otherwise result in fraud.

- Technical or logical – these are usually concerned with hardware and software in some form. Typical examples of technical controls include the use of antivirus software to quarantine or delete malware, and firewalls to block unauthorised network intrusion.

Who should be involved in the identification of existing controls?

As with the threat and vulnerability assessments covered earlier in this chapter, the information asset owners should be the first port of call for this activity, since they may well be aware of many of the controls already present for their information assets. However, other parts of the organisation will be able to provide input on this, such as the IT department, human resources and the organisation’s information security team.

A typical controls identification form might look something like that shown in Figure 5.6.

SUMMARY

In this chapter, we have examined different types of threat and vulnerability, the process by which we assess them, and briefly looked at the types of mitigating controls that may already be in place to protect the assets.

We now need to move on to the next stage of the process, which is to assess the likelihood of a threat taking advantage of a vulnerability, how we analyse the resultant risk, and how we evaluate it before treatment can be undertaken.