Chapter 11

Images of Leadership

Can Crooked Kites Fly?

Ideally we would all be versatile leaders who see the world through multiple lenses. In reality, most of us have a narrower field of vision. We prefer some ways of interpreting reality and neglect others. If our preferences were measured and plotted on a four-dimensional grid, we’d look lopsided. The shape of our leadership “kite,” depicting our cognitive leanings, can position us for success—or disaster. It all depends on how well we can adapt our mental images to align with the challenges we face.

You don’t have to be equally comfortable with all four frames. If certain areas fall outside your comfort zone, expand your field of vision—or work with someone who can help cover for your blind spots. That approach paid off for Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. The shy and geeky Zuckerberg is strong on ideas and technology but weak on executive presence. He was wise enough to complement himself with his chief operating officer, Google veteran Sheryl Sandberg. She brought a Harvard MBA, interpersonal skills, and a steady, adult hand to a company known for its chaotic, frat house atmosphere. “The dynamic on the management team,” Zuckerberg commented, “has improved a huge amount since she joined.”1 Sandberg focuses on management, public relations, and marketing, leaving Zuckerberg free to indulge his passion for the Facebook website. “Sandberg’s hefty portfolio and her fluid, trusting relationship with Zuckerberg are liberating for him. She does all the things he doesn’t want to do so he can focus on what he likes.”2

Every pattern has virtues and shortcomings, and works better in some situations than in others. In this chapter, we look at prominent business leaders who have made their crooked kites fly. As you study their examples, reflect on how well your preferences serve you now and will continue to serve going forward. (If you have not already done so, use the Leadership Orientations survey in the Appendix to assess the shape of your own leadership kite by completing the survey, plotting your scores on the figure, and connecting the dots. An online version of the instrument is available at http://www.josseybassbusiness.com/2013/07/assessment-leadership-orientations-self-assessment.html.)

METRICS MAESTRO: AMAZON’S JEFF BEZOS

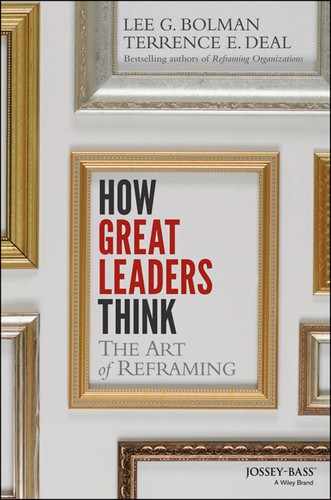

In 2005, with Amazon’s profits and stock price sinking, a business journalist wrote that it was time for Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and longtime chief executive, to turn over the reins to a professional manager with deep operations experience.3 The writer pegged Amazon as a retailer gone adrift that needed someone to jack up profit margins. Bezos, who had much bigger plans for Amazon, ignored the advice and kept after his goal of expanding his company into the largest Internet purveyor of almost everything, including e-readers and web services. Seven years later, in 2012, Forbes rated Bezos the best CEO in America: “the corporate chief that others most want to meet, emulate and deify.”4 A brilliant strategist, demanding leader, and one of the smartest guys in any room, Bezos is a contemporary example of a leader whose strong structural orientation is central to his success. Figure 11.1 shows our estimate of Bezos’s frames configuration.

Figure 11.1. Jeff Bezos’s Leadership Configuration

The structural frame dominates, closely followed by a strong symbolic orientation. The combination is captured in a phrase Bezos uses to describe Amazon: “a culture of metrics.”5 Bezos has also shown political savvy in navigating Amazon’s many external battles with competitors and content creators (such as publishers and authors). At the heart of Bezos’s approach to leadership is a relentless focus on the customer: “Amazon tracks its performance against about 500 measurable goals. Nearly 80% relate to customer objectives. Some Amazonians try to reduce out-of-stock merchandise. Others race to build a bigger library of downloadable movies. Intricate algorithms turn one group of shoppers’ past habits into custom recommendations for new customers. Hourly best seller lists identify what’s hot. Weekly reviews keep track of who is on course—and where corrective attention is needed.”6

Bezos’s focus is crystal clear: the best possible customer service at the lowest possible cost. He pays little attention to the human resource proposition: “if you take care of your people, they’ll take care of your customers.” He flattens subordinates with comments like, “Are you lazy or just incompetent?” or “This document was clearly written by the B team. Can someone get me the A team document?”7 Bezos believes in “coddling his 164 million customers, not his 56,000 employees.”8

He is obsessive about minimizing costs that don’t benefit consumers. That’s why Amazon executives fly coach and work at cheap, particleboard desks. At one distribution center, as an alternative to the cost of air conditioning, Amazon had paramedics on standby during heat waves to aid employees overcome by heat. Amazon’s tough approach produced various forms of employee resistance, including theft, unionization efforts, and one creative worker’s own do-it-yourself job enrichment program. He created a little cave for himself in an obscure corner of a distribution center, furnishing it with items borrowed from Amazon’s shelves. He punched in each morning, spent the day relaxing in his refuge, and punched out at night. His career was brief.

Bezos’s salary, less than $100,000, hasn’t budged since 1998 (though his Amazon stock has made him rich; Forbes estimated his wealth at $27 billion in late 2013). But he is a risk taker who will spend big to build the business. He invested heavily in Kindle for years before it finally became a viable product. More recently, he announced a plan to use midget drones to fly packages directly to the customer’s door.

Amazon’s success depends on making it as quick and easy as possible for customers to find what they’re looking for and get it delivered promptly to their home or office. This means that the website (where customers browse and buy) and the distribution centers (that turn digital orders into physical shipments) must be tightly aligned. Bezos and Amazon continually obsess over making sure systems perform.

Bezos is a hands-on leader who reads customer emails to stay in touch with what’s working and what isn’t. He tracks the metrics, pays close attention to operational specifics, relentlessly attacks waste, sets demanding targets, and is vigilant about ensuring accountability. Amazon has discovered, for example, that even a 0.1-second delay in rendering a web page can produce a 1 percent drop in customer activity, so Bezos pushes for constant effort to make the site faster and more responsive.

Amazon’s many metrics and huge database on customer behavior are a treasure trove for continuous improvement. Efforts to give you precisely what you’re looking for and to get it to you on time are relentless. In 2011, Bezos was proud that Amazon kept its promise to deliver goods to meet the Christmas deadline 99.99 percent of the time, but this still meant that they missed once in every ten thousand shipments. He wanted to get that number to 100 percent, and was not happy when many Christmas gifts missed the holiday because delivery partners such as UPS couldn’t keep up with the holiday demand in 2013.

Jeff Bezos’s leadership formula combines a strong emphasis on structure and technology with a demanding, customer-centric culture. One reason it works is that Amazon customers transact business with a website, not people. Amazon customers have learned not to expect friendly sales clerks who offer a cheerful greeting or in-depth product knowledge. Instead, customers reach a site that makes it easy to find preferred or panned needles in haystacks. The result is a business that consistently ranks in the top ten for customer service among online retailers. There are other ways to achieve success in online retailing, however. Surprisingly, one of the clearest contrasting examples is Zappos, a business that Amazon bought for roughly a billion dollars in 2009.

LEADER OF THE TRIBE: ZAPPOS’S TONY HSIEH

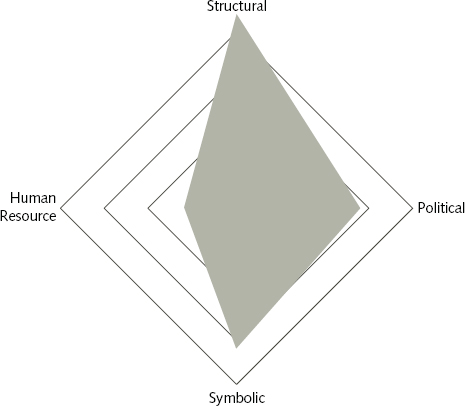

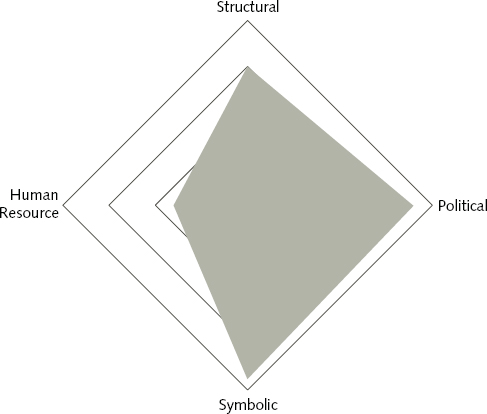

Zappos began when a frustrated shoe buyer, Nick Swinmurn, couldn’t find what he wanted in local stores or online. He decided to launch a website, shoesite.com, that he soon renamed Zappos.9 Needing capital, he approached Tony Hsieh and Alfred Lin, who headed a small investment firm with the playful name Venture Frogs. Hsieh and Lin eventually pumped in more than $10 million.10 Hsieh came on board as co-CEO and then took over when Swinmurn moved up to board chair. Hsieh had plenty of room to practice his unorthodox brand of leadership, centered on a few key ideas. Figure 11.2 shows our estimate of Hsieh’s frames configuration.

Figure 11.2. Tony Hsieh’s Leadership Configuration

Delivering Happiness is the title of Hsieh’s book about Zappos. Inspired in part by a customer who wrote that Zappos delivers happiness in a box, Hsieh is passionate about his conviction that if an organization delivers happiness to employees, they’ll do the same for customers, whose loyalty will make the business successful.

“Fun” and “weird” are two of the words most often used to describe what it’s like to work at Zappos. The company isn’t unique in offering its people free food and snacks, computers in an Internet café, or frequent parties. But it’s one of the few where singing, dancing, and costume parades are commonplace. Or where employee creativity shines in dozens of online videos about life at Zappos. These include a Zappos Family Musical11 and a clip showing a Zappos employee celebrating happy hour by slapping the CEO on his face.

Hsieh describes Zappos’s culture as the company’s number-one priority, and adds, “Our belief is that if you get the culture right, then most of the other stuff—like great customer service or building a long lasting, enduring brand—will happen naturally.”12 Zappos has anchored its culture in a set of core values that include “Deliver WOW Through Service,” “Embrace and Drive Change,” “Create Fun and a Little Weirdness,” “Be Adventurous, Creative, and Open-Minded,” and “Pursue Growth and Learning.”

Before Hsieh joined Zappos, he cofounded a successful Internet firm, Linkexchange.com, but eventually decided to sell the business (to Microsoft in 1998 for $265 million) because he no longer enjoyed coming to work. The fatal error, he believed, had been hiring for skill rather than cultural fit. Hsieh didn’t want to make that mistake again, and every Zappos job applicant is interviewed for alignment with the company’s core values. After they’ve been through initial training, Zappos offers new employees $2,000 to quit. Few accept, but it’s a powerful test of commitment and a way to weed out people who aren’t right for the culture.

All new employees, regardless of position, go through a training program that includes a week at the Zappos distribution center in Kentucky, and a tour at the call center talking to customers. Most of Zappos’s business comes from the website rather than the phone, but the call center gives new employees a way to get to know the customers and Zappos’s customer service values. Unlike most call center workers, Zappos employees don’t use scripts and aren’t measured on efficient use of time. Instead, their job is to do what it takes to make customers happy. If it takes an hour or two to solve a customer’s problem, or if they have to go to a competitor’s website to find what a customer wants, that’s what’s expected.

Creativity, fun, and weirdness intermingle to give customers more than they expect. Zappos customers often use the word “love” to describe their feelings about the site, raving about the selection, service, return policy, and free shipping in both directions. That pays off in loyal customers who keep coming back.

AUTHENTIC ENGINEER: XEROX’S URSULA BURNS

After twenty years of climbing the ladder at Xerox, Ursula Burns was ready to quit. She didn’t see much future in a company with a mountain of debt, no cash, and a corrosive culture of executive infighting. The stock price had fallen from $64 to $7 a share, and a CEO recruited from IBM had been fired after serving less than a year. Still, colleagues and board members told Burns that Xerox needed her, and the new CEO, Anne Mulcahy (profiled in Chapter Six) convinced her that she could help save the company.

Mulcahy and Burns were both Xerox lifers who had known each other for years, but they had come up through different paths: Mulcahy via sales, Burns through engineering and operations. One of the first assignments Burns took on for Mulcahy was to persuade unions that Xerox had to outsource many of its manufacturing jobs to survive. It was a tough sell, but Burns used her basic approach to leadership: “One of the things I’ve learned is that if you can know your facts, and you build up your opinions with some facts and data, as well as some emotional conviction, you can generally get people to listen to the general story and direction.”13

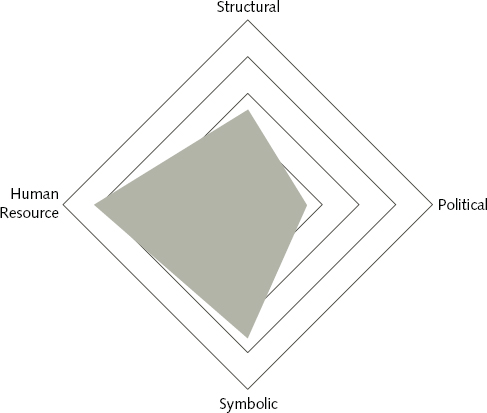

The unions bought her argument that fewer jobs were better than no jobs. When Mulcahy retired as CEO in 2009, she and the board agreed that Ursula Burns should take over the job. Burns’s promotion generated a rash of media attention because of two firsts: Burns was the first African American woman to head a Fortune 500 company and the first woman to succeed another woman as CEO of a major U.S. business. Figure 11.3 illustrates Burns’s leadership configuration.

Figure 11.3. Ursula Burns’s Leadership Configuration

Burns’s leadership configuration shows strengths across all four frames, but she is highest on structure and human resource, lowest on the political frame. The pattern reflects her background as an engineer who worked her way up to head worldwide manufacturing for Xerox. Her structural leanings were evident in her willingness “to do whatever it takes—dismantle the company’s manufacturing unit that shaped her career; cut back or eliminate products that once defined the Xerox brand; branch out into uncertain (and risky) new areas of business—in an effort to reposition the company in an era of technological upheaval.”14

Her signature initiative was persuading Lynn Blodgett, the CEO of Affiliated Computer Services (ACS), that merging with Xerox would be a win-win for both companies. Burns saw ACS, a $6 billion supplier of back-office services, as the perfect partner to accelerate a shift in the Xerox business mix toward less emphasis on hardware and more on services. ACS had multiple suitors, but Burns helped seal the deal by sending Blodgett on a tour of Xerox’s European research center in France. For a data guy like ACS’s Blodgett, it was love at first sight. “I was already happy with our technology,” he says. “But this was going to make an immediate difference to us.”15

Once the ACS merger was in place, Burns deployed her people skills—a combination of hugs and straight talk—in a campaign to convince Xerox managers that the company’s success required less “terminal niceness” and a lot more candor. In effect, she was hoping to convince her colleagues to be more like her. Burns’s style had always been to tell it like she saw it. She was known for her directness rather than her tact, which sometimes annoyed her bosses but had helped her career.

Burns saw her leadership approach as more about people than politics. Women, she felt, had “been taught to nurture and work in groups. You’ve been handed something to take care of—here’s a baby, here’s someone to dress—there is this natural ability to include more than compete. Now, there’s always competition. I definitely compete, but the role of competition can be too absolute—winning at any cost. It’s just not there for me. More of a balance is there for me.”16 Early in her career, Burns’s talent compensated for her lack of political savvy, but mentors helped her polish the rough edges, improve her listening skills, and develop the political skills to move up in a very competitive environment.

WARRIOR ARTIST: APPLE’S STEVE JOBS

There was never any doubt about Steve Jobs’s genius, and if you look at his profile, there’s very little doubt that he saw organizations as political contests. In 1985, he found himself locked in a battle with just about every senior manager at Apple, a company he had cofounded with Steve Wozniak nine years earlier. Apple’s marketing chief slammed Jobs for “management by character assassination.”17 John Sculley, the CEO whom Jobs had lured away from PepsiCo, reluctantly confronted his former patron for “badmouthing him as a bozo behind his back.”18 After Sculley learned that Jobs was planning a coup to push him out, he and the board agreed that Jobs had to go.

Being sacked took the wind from Jobs’s sails for a time. “It was awful-tasting medicine but I guess the patient needed it.”19 After his bruised ego healed, he went on to invest $50 million in a small computer graphics unit that evolved into Pixar. There, lessons learned at Apple and his failed startup, NeXT, served him well. Jobs understood more clearly that the way to build great products is to build a cohesive organization, and his way of treating people had softened somewhat.

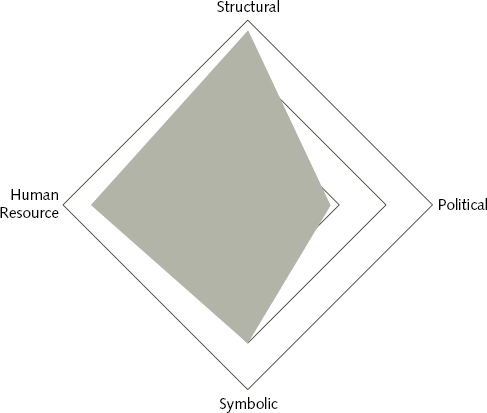

In 1997, Jobs returned to rescue Apple from a death spiral. He was much like the leader fired from Apple twelve years earlier: demanding and charismatic, charming and infuriating, erratic and focused, opinionated and receptive. The difference was in how he thought and how he led. In short order after he returned, he radically simplified Apple’s product line, built a loyal and talented leadership team, and turned his old company into a hit-making machine as reliable as Pixar. Jobs’s leadership configuration is shown in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4. Steve Jobs’s Leadership Configuration

Jobs was a master of the symbolic frame. The public knew him as a charismatic salesman whose flair for drama could transform product announcements into compelling theater that captivated the media and the public. He was also a design maven who would settle for nothing less than one “insanely great” product after another. Those who worked with him talked about “Steve’s reality distortion field” and “the world according to Steve,” reflecting his flair for framing any project or product as an opportunity to “put a dent in the universe.” In introducing new Apple products, he transformed digital boxes into mystical wonders conjured by a magical wizard. In advance of a launch, he stoked the fire of expectations and cultivated the media. In the run-up to the launch of the iPhone in 2007, Jobs called the editor in chief at Time, telling him that Apple was about to announce the greatest thing it had ever done. He added that he wanted to give Time an exclusive, but that no one at Time was smart enough to write the article. Time scrambled to find a writer smart enough for Steve, and Jobs got the publicity he wanted.

At the launch itself, Jobs connected to Apple’s history by inviting Steve Wozniak and the heroes who had developed the first Mac.20 He opened by telling the faithful, “Every once in a while a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything,” offering the Macintosh and the iPod as examples. Then he built to his climax. “Today, we’re introducing three revolutionary products of this class. The first one is a widescreen iPod with touch controls.” The audience applauded. “The second is a revolutionary mobile phone.” The applause grew louder. “And the third is a breakthrough Internet communications device.” Still more applause. He repeated the list three times, revving up his audience for the punch line. “Are you getting it? These are not three separate devices. This is one device, and we are calling it the iPhone. Today, Apple is reinventing the phone.”21 The audience laughed, cried, and cheered wildly.

Beyond the showman, Jobs was also a lifelong warrior, as we saw in his battle with Disney chief Michael Eisner (described in Chapter Seven). Short-tempered but supremely confident in his own intuition and opinions, Jobs regularly went to war with anyone who got in his way. Even though he was a rebel all his life, he also had an appreciation for organizational design. He built a distinctive structure at Apple that reflected his own personality and biases. He and his small executive team were the nerve center of a highly centralized, functional organization.22 Everything important was hammered out in that group’s Monday morning meetings. As Jobs described it, “We look at every single product under development. I put out an agenda. Eighty percent is the same as it was the last week, and we just walk down it every single week. We don’t have a lot of process at Apple, but that’s one of the few things we do just to all stay on the same page.”23 A unified team at the top could turn on a dime to exploit new opportunities or to correct error, and its job was more manageable because of Jobs’s insistence on doing only a few great things rather than trying to do everything. “Jobs often contrasts Apple’s approach with its competitors’. Sony, he has said, had too many divisions to create the iPod.”24

Like Jeff Bezos, Jobs rarely displayed the warmth and sensitivity that are often associated with human resource leadership. He cared little about other people’s feelings and was famously tyrannical and punitive. An example was a meeting he called for the team that had developed MobileMe, a software application that had failed to deliver on its promises. After asking the team to explain what MobileMe was supposed to do, he responded, “So why the fuck doesn’t it do that?” He excoriated them for tarnishing Apple’s reputation and told them they should all hate each other.25 People feared his temper, but admired his genius and craved his approval. He divided the world into “A players” and bozos. If he decided you were a bozo, your career at Apple was likely to end soon, but he knew he needed great people to produce great products, and loved working with people he respected, including Apple’s brilliant design chief, Jony Ive, and Jobs’s eventual successor as CEO, Tim Cook.

CONCLUSION

Versatility in understanding and applying all four frames is valuable for any leader, but few of us are completely symmetrical. Understanding your current strengths and weaknesses is a starting point for becoming a more balanced leader. Equally important is to recognize the degree of alignment between your configuration and the leadership challenges you face. Jeff Bezos, for example, has made Amazon successful with a business model that compensates for his disinterest in human resource issues by relying on metrics and technology. By contrast, Tony Hsieh has used his passion for people and culture to build Zappos into a customer service phenomenon. It is vital to know how well your leadership kite positions you to take on your most significant opportunities and challenges. The endless parade of leaders—like Ron Johnson in Chapter One—who crash into a wall they didn’t see is destructive to all involved. If you recognize your blind spots, you can work on expanding your vision or collaborating with others who complement your worldview because they are attuned to things that you might miss.