Chapter 5

Seeing Ourselves as Others See Us

One of the most basic and pervasive causes of leadership failure is interpersonal blindness. Many leaders simply don’t know their impact on other people. Even worse, they don’t know that they don’t know. They assume that other people see them pretty much the way they see themselves, then they blame others when things go wrong. A famous example occurred during the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, after the Republican nominee, John McCain, selected the then largely unknown governor of Alaska, Sarah Palin, to be his running mate. At first, this looked like a smart move, as Palin gave a rousing and well-received acceptance speech at the Republican convention. But Palin was new to the national political scene and lacked familiarity with many of the issues in the campaign. This sometimes got her in trouble when she had to work without a script. A legendary example was an interview on national television with anchor Katie Couric:

Couric:

You’ve cited Alaska’s proximity to Russia as part of your foreign policy experience. What did you mean by that?

Palin:

That Alaska has a very narrow maritime border between a foreign country, Russia, and on our other side, the land—boundary that we have with—Canada. It—it’s funny that a comment like that was—kind of made to—cari—I don’t know, you know? Reporters—

Couric:

Mock?

Palin:

Yeah, mocked, I guess that’s the word, yeah.

Couric:

Explain to me why that enhances your foreign policy credentials.

Palin:

Well, it certainly does because our—our next-door neighbors are foreign countries. They’re in the state that I am the executive of. And there in Russia—

Couric:

Have you ever been involved with any negotiations, for example, with the Russians?

Palin:

We have trade missions back and forth. We—we do—it’s very important when you consider even national security issues with Russia as Putin rears his head and comes into the air space of the United States of America, where—where do they go? It’s Alaska. It’s just right over the border. It is—from Alaska that we send those out to make sure that an eye is being kept on this very powerful nation, Russia, because they are right there. They are right next to—to our state.

The interview went viral in the media and on the Internet, and much of the commentary focused on Palin’s lack of foreign policy depth. But note Palin’s genuine puzzlement about the response she got. “It—it’s funny that a comment like that was—kind of made to—cari—I don’t know, you know? Reporters—.” Palin’s comments made sense to her, so she figured there must be something wrong with her critics, those liberal reporters from the “lamestream media” who were out to get her.

Palin is not alone. She provides only one of countless examples of a lack of self-awareness that chronically bedevils leaders, whether on the world stage or in much more mundane situations. A routine example is a boss, B, who thinks he’s coaching a subordinate, S, whereas S thinks B is constantly micromanaging. Over time, the boss gets more and more disappointed because S doesn’t respond as enthusiastically as he expects. He wonders why S doesn’t want to learn and can’t follow simple instructions. Meanwhile, S becomes more and more frustrated with a boss who constantly interferes, gives dumb orders, and makes it harder for her to do her job. Because the boss has no clue about the gap between how he sees himself and how S sees him, his efforts to coach just make things worse. Why are gaps like this so widespread and persistent? If you look carefully at the following case, you can see how interpersonal blindness can crop up right before your eyes in a routine encounter.

ELLEN AND DON

Ellen, a manager in an insurance company, braced for a challenging meeting with Don, one of her subordinates. Don was bright, talented, and willing to work, just as Ellen had hoped when she hired him fresh out of college several months earlier. But his attitude was another matter. Graduating in a year when jobs were scarce, Don had accepted the administrative support role that Ellen offered him, but he wasn’t happy about it. He continually complained that as a college graduate, he was underpaid and overqualified for the job. Now Ellen had an opening for an underwriter and had decided to offer Don a position as a trainee.

We’ll eavesdrop on an abridged version of their conversation. Note that the right-hand column shows what they said to one another, while the left column shows what Ellen was thinking and feeling, but not saying (based on her recollections after the meeting). As you read, ask yourself how well Ellen is handling the leadership challenge she faced in this meeting. If you were in her shoes, would you do anything differently?

| Ellen’s Underlying Thoughts | What Ellen and Don Said |

| Ellen: We’re creating a new trainee position and want to offer it to you. The job will carry a salary increase, but let me tell you something about the job first. | |

| I wonder if his education makes him feel that society owes him a living without any relationship to his abilities or productivity. | Don: OK. But the salary increase has to be substantial so I can improve my standard of living. I can’t afford a car. I can’t even afford to go out on a date. |

| Ellen: You’ll start as a trainee working with an experienced underwriter. It’s important work, because selecting the right risks is critical to our results. You’ll deal directly with our agents. How you handle them affects their willingness to place their business with us. | |

| How can he be so opinionated when he doesn’t know anything about underwriting? How’s he going to come across to the people he’ll have to work with? The job requires judgment and willingness to listen. | Don: I’m highly educated. I can do anything I set my mind to. I could do the job of a supervisor right now. I don’t see how risk selection is that difficult. |

| Ellen: Don, we believe you’re highly intelligent. You’ll find you can learn many new skills working with an experienced underwriter. I’m sure many of the things you know today came from talented professors and teachers. Remember, one of the key elements in this job is your willingness to work closely with other people and to listen to their opinions. | |

| That’s the first positive response I’ve heard. | Don: I’m looking for something that will move me ahead. I’d like to move into the new job as soon as possible. |

| Ellen: Our thought is to move you into this position immediately. We’ll outline a training schedule for you. On-the-job and classroom learning, with testing at the end of each week. | |

| We owe him a chance, but I doubt he’ll succeed. He’s got some basic problems. | Don: Testing is no problem. I think you’ll find I score extremely high in anything I do. |

At first glance, this conversation might seem routine, almost ho-hum. Look a little deeper, though, and you see how far it went off the rails. Don can’t understand why no one recognizes his talents, but has no clue that his actions continually backfire. He wants to impress Ellen, but his obsessive self-promotion reinforces his image as an arrogant candidate bound for failure. Don doesn’t know this, and Ellen doesn’t tell him. Instead, she tells him, “We think you’re intelligent,” at a moment when she’s feeling, “You’re opinionated and don’t listen.” She has good reason to doubt Don’s listening skills, as he doesn’t seem to get the message that she’s worried about his people skills. If he can’t listen to his boss, what’s the chance that he’ll hear anyone else? Yet she leaves the meeting with the intention of moving Don into a new position while expecting that he’ll fail. She colludes in a potential train wreck by skirting the topic of Don’s self-defeating behavior. In protecting herself and Don from a potentially uncomfortable encounter, Ellen helps to ensure that no one learns anything.

There’s nothing unusual about the encounter between Ellen and Don. Similar things happen all the time. The Dons of the world dig themselves into a hole. The Ellens help them shovel. One management expert, Chris Argyris, calls it “skilled incompetence”—using well-practiced skills to produce the opposite of what you intend.1 Don wants Ellen to appreciate his university-acquired virtues. Instead, he strengthens her belief that he’s arrogant and naive. Ellen wants Don to recognize his limitations, but unintentionally reassures him that he’s fine as he is. This sort of interpersonal misfire happens to all of us—more often than we realize. We don’t walk our talk. Others notice the gap, but don’t tell us. We see inconsistencies in others but not in ourselves. As a result, no one learns much, and ineffectiveness reigns unchecked.

This is one major reason that leaders do strange and unproductive things at work. They say one thing and do another, oblivious to their hypocrisy. They keep making the same mistakes, but feel insulted by feedback and reject offers of help or coaching. They rehash tired clichés (“People are our most important asset”; “Work smarter, not harder”), yet can’t understand why everyone ignores them.

The question of personal blindness has perplexed people since ancient times. Some twenty-five hundred years ago, Lao-tzu, a very wise Chinese philosopher, got to the heart of the issue: “Those who know others are wise. Those who know themselves are enlightened.”a In the old days, the enlightened were scarce, and hypocrites were abundant. Look around your organization. You may conclude that not much has changed. In growing up, most of us have learned to build a self-image grounded in fashionable virtues. We hold on to these saintly self-images because they’re a ticket to getting respect from others—and from ourselves.

But daily life often presents situations where acting on virtue is inconvenient. If we held to our espoused values, we might not keep the boss happy. Someone else might get that promotion we really want, or we might be on the losing side in a political scrap. So it’s tempting to let virtue take a backseat to self-interest. It’s a way to get through life’s daily challenges without too much pain and suffering. But it would be awkward and uncomfortable to notice that we are inconsistent. Almost no one wants to see themselves as dishonest or devious, so why not just gloss over inconsistencies and pat ourselves on the back for being realistic and practical?

Staying blind is easier than you might think because we are all unconscious coconspirators in a social contract to keep each other comfortably unaware of discrepancies. We saw it in the conversation between Ellen and Don, and it’s right before your eyes in countless business meetings. Here’s the bottom line for leaders: regardless of how you see yourself, what matters is how you’re seen by those you hope to lead. The question is, how do you make sure you’re in touch with your constituents?

SELF-AWARENESS

Leaders develop self-awareness through ongoing learning about their actions and their impact on others. It’s hard to know how others see you unless they tell you. Often, they don’t. Or they do it badly. And much of the time, we’re not sure we want them to. We get caught between the need to know and the fear of finding out. So we often forgo the feedback opportunities that are available. This is a major reason that so many organizations have implemented one version or another of 360-degree feedback, which they hope will give people the feedback they need but aren’t sure they want, or don’t know how to get on their own.

Such activities are often invaluable, but they’re not sufficient as a substitute for ongoing learning. Too many wannabe leaders make the mistake of believing that they should present themselves as not needing to learn from anyone because they already have all the answers. Smart leaders know better, and, if you understand a few basic principles of interpersonal feedback, you can accelerate your own learning and perhaps improve others’ as well.

- Ask and you shall receive

People often withhold feedback because they’re not sure you really want it. Asking is the easiest way to get others to open up. Skill in framing the right questions helps, and persistence helps even more. If you simply ask a friend or colleague, “What did you think about my [report/speech/tie/dress],” the first response you get will often amount to vague reassurance (“Seemed fine to me.”). Not much help. Follow up with more specific probes: “What do you think worked best?” “What could I have done to make it better?” “What message do you think the audience took away?” People are reluctant to tell us more than we want to know. Persistence and specificity make your requests clear and credible.

- Say thank you

The risk of asking for feedback is that you may not like what you hear. If that’s true, say so, because the other person will sense it. But be sure to thank anyone who tries to help. If you respond to a gift by rejecting it, criticizing it, or inducing guilt, the flow of future offerings will dry up fast.

- Ask before giving

Feedback can do more harm than good. When someone doesn’t want it, catching him or her off guard will usually breed suspicion and defensiveness rather than listening. How do you know if feedback is welcome? Much of the time, people aren’t expecting or even thinking about it. You can usually find out with a few simple questions. One gentle but reliable approach is to ask how they felt about whatever they did: “How did you feel your presentation went?” “How do you see your role on this team?” This kind of question gets others thinking. They may ask for your reactions or, at least, give you an opening to ask them if they’d like to hear more. In any event, their response will help you assess whether they’ll welcome your input.

- When asked, give your best

With or without prompting, people will sometimes solicit your reactions to something they did. Resist the temptation to offer reassuring platitudes, but don’t jump to the opposite extreme of brutal confrontation: “I can’t tell if you’re lazy or just stupid!” Instead, describe as specifically as you can what you saw and how you reacted. It’s not much help to tell someone, for example, “The whole presentation was a flop.” A more specific version of the same message might be, “Your presentation made more points than I could keep up with; after a while, I lost track of your main message.”

- Tell the truth

This is familiar advice that almost everyone endorses and almost everyone violates. The primary barrier is fear. We’d say what we think—if we weren’t afraid of the consequences. Take the following conversation between a boss and a subordinate. They’re both about to be killed (along with some other people whose fate is in their hands). Why? Two reasons. First, the boss has made a bad mistake, though he doesn’t know it or can’t admit it. Second, the subordinate is offering subtle hints instead of being direct about his concerns.

The boss is the captain of a jet airplane (in this case a DC-8 carrying cargo for the U.S. Air Force). The subordinate is his copilot. They are flying an approach into Cold Bay, Alaska. The airport is surrounded by mountains, and there are only two safe routes in. Both pilots know this, and both are looking at the same approach chart. But the captain, who is flying the plane, is off track. Looking out the window won’t help, because it’s dark and they’re in the clouds.

(5:36 a.m.)

Captain:

Where’s your DME? [Translation: How far are we from the airport?]

Copilot:

I don’t have a reading. Last reading was forty miles.

(5:37 a.m.)

Copilot:

Are you going to make a procedure turn?

Captain:

No, I . . . I wasn’t going to.

(Pause)

Copilot:

What kind of terrain are we flying over?

Captain:

Mountains everywhere.

(Pause)

(5:39 a.m.)

Copilot:

We should be a little higher, shouldn’t we?

Captain:

No, forty DME [forty miles from the airport], you’re all right.

(5:40 a.m.)

Captain:

I’ll go up a little bit higher here. No reason to stay down that low so long.

(The captain climbs briefly to four thousand feet, then starts down again.)

(5:41 a.m.)

Copilot:

The altimeter is alive. [Translation: We’re real close to those mountains.]

(5:42 a.m.)

Copilot:

Radio altimeters. Hey, John, we’re off course! Four hundred feet from something!

Six seconds later, the airplane was destroyed when it crashed into a mountain.2

The conversation captured on the cockpit voice recorder makes it clear that the copilot was worried. But instead of saying so, he tried gentle hints (“What kind of terrain are we flying over?”). He became direct only when it was too late (“Hey, John, we’re off course!”).

Similar cockpit dynamics may have contributed to the crash of an Asiana Airlines Boeing 777 at San Francisco in July 2013. The captain flying the airplane was a highly experienced pilot, but he was new to the 777 and still learning. (He was transitioning from Airbus equipment with somewhat different control systems.) The captain later told investigators that he was feeling very stressed during the approach to San Francisco, though he didn’t say that during the flight. He thought he had the controls set to maintain the correct speed automatically, but he was mistaken, and the plane gradually fell below its target speed. The experienced check pilot who was flying as a monitor and coach should have detected any significant deviations from correct procedures, but either he didn’t notice or was too polite to say anything. Airspeed is a critical factor in landing an airplane, and an airspeed indicator was plainly visible. Although it is conceivable that neither of these two experienced pilots realized they were getting into trouble, it is more likely that at least one of them did know but chose not to mention it, perhaps for fear of making a bad situation worse. About a minute before the accident, a junior relief pilot sitting in the jump seat politely commented, “Sink rate, sir” (a gentle hint that the plane was descending too quickly). He repeated the remark five seconds later, but no one seemed to get the message. The captain and check pilot continued on a path to catastrophe, making routine callouts. The plane approached the runway too low and too slow, but only at eight seconds before the crash did the check pilot twice say “speed.” Less than two seconds before impact, he called, “Oh [expletive], go around.” That order to abort the landing came too late.3 The plane stalled, the rear end hit a seawall at the end of the runway, and the tail separated. Three teenage girls in the back of the plane were killed, and about 180 other passengers were injured, some critically.

Most situations you encounter at work aren’t likely to be matters of life and death. But the costs of not speaking up can still be very serious. It’s tempting to muddle along and avoid rocking the boat. If you’re in a truly toxic workplace, that may be a safe and sane option, even if it mires you deeper in a rut. But you’ll become a better leader if you learn from others and they learn from you. It’s a rare and potent skill.

LEADERSHIP SKILLS: ADVOCACY AND INQUIRY

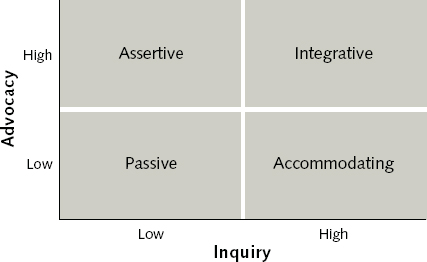

It’s easy to see that leaders need to communicate clearly and persuasively to advocate effectively on behalf of their mission and constituents. But many leaders fail to recognize that they also need to be good at inquiry. Probing with questions and observation enables them to learn from experience and to acquire information they need if they are to understand what’s going on. Leaders are high on advocacy when they are communicating clearly and effectively. They are high on inquiry when they are actively asking questions and encouraging feedback to get important information (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. Advocacy and Inquiry

Leaders need continuing practice and feedback to enhance their skills in both advocacy and inquiry. The ability to combine them leads to a much better chance of being effective in the challenging environment of an airline cockpit, or the more mundane circumstances of Ellen’s encounter with Don. Let’s revisit their dialogue to examine how Ellen might have been more direct so as to generate learning for Don—and maybe for herself as well. Assume that the conversation starts exactly as before, but Ellen responds differently to Don because she follows two simple rules: (1) she says what’s on her mind, and (2) she asks questions in order to learn—and to confront.

| Ellen’s Underlying Thoughts | What Ellen and Don Said |

| Ellen: We’re creating a new trainee position and want to offer it to you. The job will carry a salary increase, but let me tell you something about the job first. | |

| I wonder if his education makes him feel that society owes him a living without any relationship to his abilities or productivity. | Don: OK. But the salary increase has to be substantial so I can improve my standard of living. I can’t afford a car. I can’t even afford to go out on a date. |

| Ellen: I understand you want to earn more, but are you aware that pay is based on how much you contribute rather than how much you want? | |

| Don: Um, I guess. | |

| Ellen: You’ll start as a trainee working with an experienced underwriter. It’s important work, because selecting the right risks is critical to our results. You’ll deal directly with our agents. How you handle them affects their willingness to place their business with us. | |

| How can he be so opinionated when he doesn’t know anything about underwriting? How’s he going to come across to the people he’ll have to work with? The job requires judgment and willingness to listen. | Don: I’m highly educated. I can do anything I set my mind to. I could do the job of a supervisor right now. I don’t see how risk selection is that difficult. |

| Ellen: Have you ever been a supervisor or an underwriter? | |

| Don: Well, not exactly, but I still don’t see that they’re that hard. | |

| Ellen: When you tell me you already know how to do something you’ve never done, can you see why I worry that you’re being unrealistic about yourself? | |

| Don: I still say I can do whatever I put my mind to. | |

| Ellen: Right now, can you put your mind to listening to what I’m saying? | |

| Don: (pauses, looking surprised) Uh, well, yeah, that’s what I’m doing. | |

| Ellen: Good. I want to be sure you understand that we expect a trainee to start with the attitude, “I’m here to learn,” not “I already know everything.” Are you comfortable with that? | |

| That’s the first positive response I’ve heard. | Don: Well, OK, if that’s what I need to do. |

| Ellen: Don, we believe you’re highly intelligent. You’ll find you can learn many new skills working with an experienced underwriter. I’m sure many of the things you know today came from talented professors and teachers. Remember, one of the key elements in this job is your willingness to work closely with other people and to listen to their opinions. | |

| Don: I’m looking for something that will move me ahead. I’d like to move into the new job as soon as possible. | |

| Ellen: Our thought is to move you into this position immediately. We’ll outline a training schedule for you. On-the-job and classroom learning, with testing at the end of each week. | |

| Don: Testing is no problem. I think you’ll find I score extremely high in anything I do. | |

| Ellen: Does that include listening and openness to learning? | |

| Don: Um, sure. |

In this conversation, unlike the one at the beginning of the chapter, Ellen spoke directly to the issues that concerned her, and deftly punctured Don’s bravado with a series of questions designed to trigger reflection on his part. Instead of letting Don off the hook with his inflated claims, she asked him to explain and gently confronted him. When, for example, he insisted that he scores high on anything he does, she asked if that included listening to her. Don was surprised by a question that nudged him to think about a skill he’d neglected. Ellen combined advocacy with inquiry in her statement, “I want to be sure you understand that we expect a trainee to start with the attitude, ‘I’m here to learn,’ not ‘I already know everything.’ Are you comfortable with that?” She clarifies expectations, and her question at the end is powerful because it asks for acknowledgment and commitment.

Ellen, if she is wise, will not expect Don to be transformed by one conversation. But in questioning rather than ignoring Don’s self-aggrandizement, she prods Don to reflect on his actions and to realize that some of his patterns are self-defeating. It’s hard to make someone learn, but you improve the odds when you interrupt ineffective patterns and provoke self-reflection. Good leaders are adept at both advocacy and inquiry.

CONCLUSION

Leaders spend most of their time communicating with others, but if they don’t know how others see them, they are flying blind, and their messages will often go awry. It is hard to become a great leader without being a great listener and learner. Interpersonal communication is central to leadership, but it is inherently rife with traps and snares that leave both leaders and subordinates confused and frustrated. Leaders contribute to this muddled interplay through their own personal blindness and their lack of awareness of basic principles and skills, such as advocacy and inquiry, that improve leaders’ ability to communicate with others more effectively.

We’ve looked at the power of the structural and human resource frames. Both are essential to enlightened leadership, but even together, they are still not enough. Neither grapples very well with the political dynamics that are an inevitable feature of social life. That’s where we’ll go in Chapter Six, the first of the political chapters.