Chapter 22

The European Climate Exchange

Where to elect there is but one, ‘tis Hobson's choice—take that, or none.

—Thomas Ward1

My mother's stories about Europe had always fascinated me as a child. She often spoke of sailing on the Mauretania on the one trip she made back home. She regaled my family with the ship's beauty and elegance—its polished mahogany bars, exquisite stairways, and its record time in crossing the Atlantic. I lived and breathed my mother's glories, but it wasn't until I was 33 that I made my first trip to Europe and realized what had inspired her stories. I was determined to visit the great capitals of Europe and walk in my mother's footsteps, not as a tourist but as a businessman and an academic.

Tapping into the European Psyche

I made my first trip to London in 1979. Shortly after landing, I discovered that the baggage handlers were on strike. Since the carousels were not working, we had to pick through piles of luggage that the management brought out by hand. This unlucky incident reminded me of a satirical line from the Peter Sellers movie, I'm All Right Jack, a comedy that satirized the trade unions, workers, and their bosses: “We do not and cannot accept the principle that incompetence justifies dismissal. That is victimization.” The Brits certainly knew how to make fun of themselves.

The United Kingdom, and London in particular, had changed dramatically during the Thatcher era. Although the economy was still bad, the country felt far more functional. It was also becoming more international. Spirits were buoyed by the successful war in the Falkland Islands. I finally began to find the London of my mother's stories.

Starting new exchanges in Europe, in some instances, was more difficult than in the United States. Futures and options markets had some presence in Amsterdam, London, and Paris, but were absent on the rest of the continent in the early 1980s. The international financial community gradually came to accept them over the next 20 years.

European environmental policy makers and NGOs were skeptical about market-based solutions to climate change, just as they had been skeptical of financial futures during the 1980s. Taxes were the policy tool of choice. However, the public sensibility regarding climate change was already a part of the European psyche, in contrast to the United States. In 1990, the European Commission proposed carbon taxes to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Policy makers believed that a tax on carbon caused higher costs of production, and therefore translated into higher prices for consumers. These higher prices would decrease demand for industrial and consumer products and result in lower emissions. The “polluter pays” principle was a policy tool supported by the environmentalists but opposed by large emitters like utilities, energy producers, and manufacturing companies. In particular, the carbon tax targeted heavy industry such as cement and steel.

The success story of SO2 emissions reductions often fell on deaf ears in Europe. Nonetheless, we remained determined to either start a new exchange in Europe or partner with an existing futures market. I continued to lecture in London and throughout the European continent between 1990 and 2000. Florence Pierre arranged a keynote address on emissions trading in Paris sponsored by the Ministry of the Environment, and a fellow board member at Sustainable Performance Group arranged a similar conference sponsored by the Club of Vienna. To reiterate, following the approval of Kyoto, attitudes toward markets grew gradually less hostile.

The process of institution-building in Europe began picking up momentum in 2001, with country-level initiatives taken by Denmark, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Norway. There was a landmark event two years earlier.

A Brief History of European Cap-and-Trade

The government of Denmark ran a mandatory cap-and-trade pilot program between 2001 and 2003 that was limited to eight electricity generators. The program involved an absolute cap on emissions, initially set at the current level of demand for electricity, to be lowered over time. Domestically, Denmark was disciplined in achieving energy savings. However, because Sweden and Norway depended heavily on hydropower for electricity generation and were experiencing periods of low rainfall, Denmark's reductions in CO2 emissions were largely offset by exporting electricity to its neighbors.2 Because of this leakage issue, Danish cap-and-trade essentially became a tax on electricity exports. The fine for noncompliance was £5.4 per tonne of CO2, and trading was limited.3

In April 2002, the United Kingdom began a voluntary cap-and-trade program, the first economy-wide scheme in the world covering all greenhouse gases.4 The program included sector-based energy intensity targets but excluded utilities. Corporations were encouraged to participate through incentive programs instituted by the government. The government set aside £215 million in incentive payments (£30 million a year after taxes) through a government-subsidized auction for companies that joined the program as direct participants.5 Companies from the private sector participated, including British Petroleum. In 1997, BP launched an internal trading program across its 150 business units, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their operations to 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2010. Each unit was assigned a quote of emissions permits and was given the option of achieving compliance through emissions reduction or purchasing reduction credits from other BP units.6 There was some price discovery and it was reported that internal prices were $7.60 per ton of CO2.7

In the meantime, the Dutch and Norwegian governments were also studying cap-and-trade pilot programs. The Dutch government had been engaged in discussions with industry since 1997 regarding an emissions trading program for NOx and launched a market trading simulation in early 2001. Norway had been active in climate policy since the late 1980s and began working on plans for a domestic emissions trading scheme to begin in 2005. Once it came to the attention of policy makers that there was a European pilot program in the works, European countries began redirecting their independent efforts in anticipation of eventually converging as member states of the EU ETS.8

Two years earlier, the European Commission had become proactive and urged the Union to develop a specific policy in response to climate change. The Commission published a green paper in 2000 that discussed greenhouse gas emissions trading within the European Union and more or less took the EU's implementation of cap-and-trade for granted.9

In the early days of the discussions on the design of the EU ETS, I made frequent visits to Brussels and London to brief policy makers on our experience with voluntary and mandatory emissions markets in the United States. During those visits, I was impressed by the high degree of professionalism and knowledge of people like Peter Vis from the European Union Environment Commission and Henry Derwent, international climate change director for the United Kingdom.

The EU program was named the EU Emissions Trading Scheme. A newly adopted policy allocated free emission allowances, called EU Allowances (EUAs), to EU members, but allowed countries to auction up to 5 percent of their allowances. This was to be increased to 10 percent once the Kyoto compliance period began in 2008. The EU ETS originally included only CO2, but was later extended to include other greenhouse gases as well in Phase II of the program (2008 to 2012), which coincided with the Kyoto compliance period.

A provision of the EU ETS stated that any unused allowances during Phase I of the program could not be used in the Kyoto compliance period from 2008 to 2012. While the environmental rationale for this provision was clear, it almost caused a disaster in the markets. I remember warning the EU officials in Brussels that this might result in much lower CO2 prices in 2007, and therefore hurt the credibility of the scheme. The senior staff understood the dangers of no banking, but believed this way to be the only way to obtain a buy-in from the environmentalists. Indeed, given that the total allocation of allowances exceeded actual emissions, prices of CO2 were driven to close to zero in 2007.

The EU ETS process moved quickly, and a directive was published stating that a three-year pilot program would commence on January 1, 2005.10 We had just conducted our first auction at CCX when we learned of this new opportunity. “First to market” had been our rallying cry, and time was limited. We had to launch an exchange in Europe if we wanted to maintain our leadership role outside of the United States.

ICE and CCX Collaborate

Our outside counsel advised us that it could take several years to establish a new futures exchange in Europe. It was more expedient to form a joint venture with an existing European exchange to expedite the process. After considering several different partners, we chose ICE to serve as our technology provider and function as the new exchange's regulatory platform. ICE had the trading screens, and a large number of their users were banks and energy companies. It was their comparative advantage and consequently ours. Many of ICE's members like BP and Shell were already actively trading on the exchange. I was also on ICE's board of directors and on good terms with the exchange's CEO and management team.

While the International Petroleum Exchange, now acquired by ICE and renamed ICE Futures, had floundered in the 1980s with a gas and oil contract, it had since been energized by an odd set of circumstances. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, NYMEX was forced to close while IPE, which was owned by ICE, stayed open, a happenstance that enabled IPE to become a force in the world energy markets. This was similar to the CBOT's open doors on Columbus Day, following the Fed's decision to target money supply instead of interest rates in 1979. The lesson to be gleaned from both events was that we would have to lean toward a world that permitted 24-hour trading, irrespective of national holidays. CCX's linkage with ICE prepared us for that eventuality, ensuring a low-cost access to existing energy traders. Such an alliance also made sense from ICE's point of view, insofar as coal and emissions trading would attract new users to the exchange's suite of energy products.

I informed the CFO of ICE of CCX's desire to establish a joint venture with ICE. The negotiations with ICE took us close to six months, and presented a number of hurdles. For example, would it be possible under UK laws and regulations to operate a new exchange while delegating its compliance and electronic platform to an existing regulated exchange? Fortunately, this turned out to be feasible.

The deal between ICE and CCX was announced in April 12, 2004. Our partnership with ICE resulted in a new entity, which we named the European Climate Exchange (ECX), to be owned by CCX but operating as an independent exchange. In late April, we announced that ICE and CCX would work together to provide a platform for a futures market in European emissions allowances. As part of the agreement, CCX would grant ICE a license to list CCX's EU products on its electronic platform. CCX was responsible for writing the emissions futures and options contracts, ECX was in charge of marketing them, and ICE helped with the marketing efforts and provided all the necessary regulatory services. The final deal called for a revenue share of 75 percent for ECX and 25 percent for ICE, with ECX bearing some technology costs and all product development and marketing expenses. The agreement lasted until 2010, to be renegotiated prior to termination. The contract provided incentives for both parties not to seek new partners for a limited time if the agreement were not renewed in 2010. It also provided a disincentive for CCX to sell ECX to ICE's competitors. We were all very optimistic about the partnership.

In addition to launching a futures exchange in the United States, we now faced the challenge of being able to raise additional capital to fund the new European venture. Fortunately, our agreement with ICE and effective marketing of the pilot program facilitated this capital raise. We had a one-for-one rights offering, whereby the original investors were given the right to buy the same amount of shares that they had initially purchased and at the same price. Once Invesco agreed to buy 29 percent of the offering, it became apparent that the underwriting would be successful. We landed some new subscribers that had passed on the first offering, and were slightly oversubscribed. We sold another 15 million shares at £1 per share, the price of the original offering. The proceeds were used to launch CCFE in addition to ECX. Our bankers and Neil Eckert were superb in their roles.

Establishing ECX

Peter Koster, the CEO of Fortis's FCM, was a former board member at Liffe. He was prudent and spoke infrequently. When he did speak, however, his remarks were intelligent and pithy. Peter was coming to Chicago with a colleague, Albert de Haan, and wanted to meet. Fortis had set up an entity called New Values with Rabobank. The purpose of the new joint venture was to set up a trading platform for spot, forward, and futures contracts on EUAs. New Values was later disbanded because Rabobank wanted to focus on spot and forward transactions, while Fortis wanted to focus on futures.

New Values was interested in buying or entering into a joint agreement with CCX. I kept this in mind, and after the deal between ICE and CCX was announced, I asked Peter if he was interested in serving as the CEO of ECX. He thought it was a great opportunity. Neil later interviewed Peter and recommended that we hire him. Peter joined the company several months later and hired Albert as commercial director. Albert worked in the power sector and knew many of the players. They were later joined by Sara Stahl, a young chemist who had worked on emissions trading at the European Commission in Brussels. She was an articulate young woman with a no-nonsense attitude, the only original employee who stayed through with the company in its brief history.

In Chicago, the CCX team worked on the research and development of ECX, and have ECX focus on marketing. Mike Walsh managed the CCX research team and they quickly started working on demand and supply fundamentals for the EU ETS. What remained for us to do was to design the contract itself, which was my favorite part. This was straightforward, given our prior experiences. The salient features of the contract, which would be named European Union Allowances (EUAs), are listed in Table 22.1.

There was some dissension regarding the tick size. From the standpoint of reducing transaction costs, I thought it should be €0.01. However, the team in Europe thought it should be higher. I yielded on the issue and we went with €0.05. Determining the launch date was a trickier ordeal. Conventional wisdom suggested that for a futures market to emerge, there had to be a well-developed spot market. In order for a spot market to emerge, there needed to be a location that enabled spot deliveries. In the case of electronic carbon allowances, this location was an emissions registry, an electronic warehouse for EUAs. The EU had proposed building a registry for each of the participating nations. However, there was one small problem. There were no registries operational as of 2004. In their absence, the market consisted of a few forward deals in brokered markets. If we simply let the dealers and brokers develop relationships with the customers, the market could evolve with a bias toward over-the-counter (OTC) deals, making it harder to develop a futures market. To solve this problem, I suggested that we make a bold decision: to go ahead with the futures launch in the absence of a spot market or certain delivery location.

Table 22.1 ICE ECX EUA Futures: Contract Specifications

Naturally, there was some uncertainty in drawing the contract specifications. We expected that the UK registry, once established, would have maximum traffic, due to London's financial might and the registry being the one that was closest to completion. Our first deliveries were in December, and we took a bold risk in denoting London to be a delivery point even though there wasn't a registry in place. I knew that the French and the Germans did not have the same institutional capacity and willingness to lead that the British had. Since the flow of allowances across individual European national registries was not feasible at the time, we expected some basis risk based on the delivery point. Mike was already at work designing financial instruments that allowed users to hedge these risks.

Thankfully we never had to use them, as the UK registry was built in May, a month after our launch. The EU eventually designed an elaborate electronic transfer system, which served as a “community independent transaction log” through which EUAs could travel from the registry of one country to that of another, very much like an electronic superhighway. Today, this system provides seamless transfer of allowances within the EU, promoting spot and futures transactions.

Neil and I decided to establish the headquarters of ECX in Amsterdam, a city with a trading heritage dating back to 1602 with the founding of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.11 More importantly, the choice of London, Paris, or Frankfurt might have led to adverse political and business consequences, as the three countries saw each other as rivals.

To market the exchange, it was critical to amass enough buyers and sellers on the opening day to send a clear signal that we were the leaders in this new environmental space. Utilities already had trading desks, so they simply had to be educated about the new EU pilot program. Trading was a natural adjunct to the utilities’ purchases of coal and sales of power. Energy producers also had trading desks.

ECX held a prelaunch seminar at the ICE offices shortly before the launch of trading. We expected a medium-size turnout, but actual attendance was far beyond modest. People began drifting into the room about 15 minutes before the seminar. By the time we began, only standing room remained. Many major oil companies, even those who refused to join CCX, were present, as were utilities and commercial banks with trading desks. I delivered some brief opening remarks before Peter and Albert discussed the contract details and the opportunities for hedgers and speculators. The groundwork laid by the various pilot programs in Europe played a constructive role in helping this pre-Kyoto pilot program. The years of effort devoted to building our brand throughout Europe, and the extensive prelaunch marketing was finally reaping its fruits.

In order to build the transatlantic bond, showcase the brand, and foster cross-marketing between America and Europe, Mike and Rafael Marques traveled to Europe in late January 2005 to join in our planned ECX road shows for Paris, London, Frankfurt, Cologne, Madrid, and Amsterdam. We were trying to cover as many people and territories as possible in a short period of time.

During this six-city trip, the CCX team tried to recruit the North American divisions of European corporations while espousing the use of ECX. Bayer, a German chemical and pharmaceutical company, was already a member of CCX. Rafael made a special trip to Bayer's headquarters, which had led the company's membership. The halls at the Bayer factory just outside of Cologne looked like a university hall, with every office name ending with a PhD title. One of the company's representatives made a comment that Rafael would never forget: “In CCX, you asked for industry's input to inform the design of the system. In Europe, the EU designed the system and then asked industry for input.”

We began trading on April 22, 2005, and in doing so, became the second exchange to offer futures trading in EUAs. Earlier, Nordpool had started to trade EUAs on February 11, 2005, and had a small but growing volume. The first ECX trade took place between BP and E.ON UK for 10,000 tonnes of CO2 at €17.05.12 The trade was cleared by Caylon and ABN AMRO. The first day saw 108,000 tonnes (108 lots) traded, with the price ranging from €16.80 to €17.40. The fact that it was also Earth Day and Ellen's birthday made it even more symbolic for me. A small group of the young crowd in the Chicago office stayed up overnight to witness the first trades.

Following the opening of ECX, carbon spot and futures exchanges proliferated throughout 2005. The European Energy Exchange (EEX) started in Leipzig on March 9, BlueNext in Paris on June 24, Energy Exchange Austria (EXAA) in Vienna on June 28. In February, even the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) listed a Certificate of Emissions Reduction carbon credit note futures, but it never took off. There was a gush of carbon funds that started to make their appearance in London.

Hedgers were early adopters and ratified the new concept of emissions trading. Many first movers wanted us to succeed and were happy to endorse ECX, thereby allowing us to use their early adoption as a sales tool while educating hundreds of users.

A major marketing effort directed toward the futures industry took place at the Swiss Futures and Options Association's annual conference in Burgenstock in September 2005. It was an opportune moment to market ECX. Since Neil had just left Brit Insurance to join CLE, I figured it was also an excellent opportunity to introduce him to the key players in the worldwide futures industry. I was teased because some of the panels included members who were retiring from the industry. I should have been among them but being a restless soul, I was busy promoting the new EU allowance futures contract.

I ran into Jim Kharouf, a Chicago-based reporter who covered the futures industry. I suggested that we grab a drink. I had an idea that could change his life: “These new markets need a focused newsletter on climate change. Carbon could become one of the biggest commodities in the world.” At the outset of financial futures, I shared similar thoughts with the CEO of Telerate and the founder of Bloomberg News. Jim was fascinated by the successes of these companies and hadn't realized that it was the publication of prices and analytics for interest rate futures that drove their initial success. Jim Kharouf eventually went on to publish the Environmental Markets Newsletter, while we helped build awareness in other broadcast and print media. ECX picked up attention in European publications such as the International Herald Tribune, Financial Times, and Euromoney.13 We still had a lot of other work left to do, however, in order to ensure the success of the markets.

The objective of ECX was to become the dominant allowance market in the EU. In addition to hosting seminars throughout Europe, we also held one-on-one meetings with the companies from the power sector and industrial corporations. Due to his background in the futures industry, Peter focused on financial players while Albert and Sara concentrated on the industrial emitters. The list of target companies was easy to determine, as the EU and its member states published lists of the largest emitters. Among the groups ECX marketed to, the industrial companies were the most difficult. For most industrial companies, futures trading was a new concept that had to be explained.

A number of surprises awaited us. Albert and Sara gave a seminar in Warsaw. Language was a barrier so a translator was hired. When the Q&A session began, there wasn't a single question. Some of that could be explained away by Polish culture—it was not in their tradition to ask questions publicly. More important than that, however, was because the translator didn't know how to translate futures into Polish. In another instance, language would become our savior. The ECX office manager in Amsterdam was Czech, and became active in recruiting CEZ, the largest utility in the Czech Republic.

There was no language barrier in Germany. Although EEX in Leipzig was where most utilities traded power, they did not have a tradition in futures trading since they ran a spot market for electricity. RWE, E.ON, and other German utilities made ECX their trading platform of choice, which helped us attract other German industrial companies.

During those years, Peter, Albert, and Sara had made more than 200 flights to and from Europe. They spent more time in planes and hotels than on the ground. In addition to this, ECX had conducted more than 50 group presentations in total, not including innumerous one-on-one meetings in our major cities on the continent. As in any new market, going to where the users were located was critical.

As in the case of CCX, we needed market makers. Although the European banks were there from the outset, Chicago was once again the source of much of the initial liquidity for ECX. Tradelink and other proprietary shops in Chicago provided liquidity for new markets. We also found other liquidity providers in a Manhattan building referred to jokingly as the Hedge Fund Hotel, due to the large number of hedge funds that were located there.

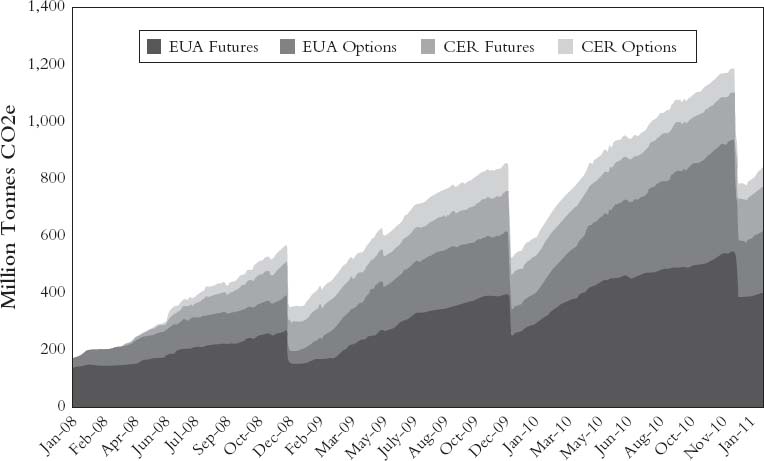

Volume and open interest grew slowly in the opening days, but this was something we were accustomed to. Exponential growth followed. The volume traded reached 94 million tonnes in 2005, 453 million tonnes in 2006, and more than 1 billion tonnes in 2007. Open interest also increased dramatically. Figure 22.1 provides graphs of volume and open interest for those first three years and beyond.

On April 25, 2006, Sara was attending a presentation by the Dutch government when an official casually mentioned that the Netherlands had been allocated more allowances than it needed. Coupled with the fact that none of the allowances issued under Phase I of the Kyoto Protocol could be banked and used in Phase II, which started in 2008, the announcement caused many attendees to leave the room in order to start shorting the futures contract. From that point on, the December 2007 futures began to fall until they finally approached zero at their expiration. Figure 22.2 is a chart of prices of the December 2007 and December 2008 contracts during the pilot program.

Despite the price plunge, the market was able to emerge with only a few small scars. This was largely because it had already been anticipated. There was a flurry of brutal press reports and finger pointing right after the incident, most of which was uninformed. Some attributed the price plunge to the lack of emissions measurements before 2005, leading to asymmetric information and initial uncertainty.14 Environmental groups were fast to point out that the EU had been far too generous with distributing carbon emission allowances in the period from 2005 to 2007, and in doing so, rewarding major polluters with windfall profits and undermining the efforts to reduce pollution.15 Even leading U.S. newspapers proclaimed that this “colored” the U.S. plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through market mechanisms.16

Figure 22.1a ECX Annual Total Volume and Settlement Price

Source: Data from IntercontinentalExchange.

Figure 22.1b Total Open Interest

Source: Data from IntercontinentalExchange.

Figure 22.2 EUA Futures Prices

Source: Data from IntercontinentalExchange.

Criticisms withered with time, but some still argued that the €15 price of EUAs was not enough to induce a change in behavior—it was estimated that behavior would change at a price of €35 and above. Once again, it was difficult to convince many that it was the expectation of prices that would stimulate inventive activity, and not the current prices. Great caution had to be exercised when making the assumption that current prices and current technology would prevail in the future.

Another criticism was that the €0.05 expiration price at the end of the pilot program was seen as justification of the failure of cap-and-trade. This missed the point that ECX was a pilot rather than a full-fledged program, whose purpose was to prepare for the Phase II (2008 to 2012) of the EU ETS. Environmental benefits were incidental and meant to be just that. The purpose of the pilot was first and foremost to build institutions and human capital. We were still in the early days of building the market infrastructure.

ECX Moves On

At the end of 2008, Peter Koster left his post as CEO at ECX to pursue other opportunities. We reflected on how much had changed around us. Over the preceding two years, London had been gradually transformed into the financial center of emissions trading. In less than three years following our IPO, six UK companies in the emissions trading space were listed on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM): XL Tech, Trading Emissions, AgCert, Ecosecurities, Econoergy, and Camco. The human capital in London also continued to grow. Engineering firms, consultancies, accountants, lawyers, and information technology providers were populating the city. Given these considerations, we made arrangements to close the Amsterdam office and move the ECX headquarters to London.

Patrick Birley had been CEO of an exchange in South Africa, and had recently moved back to London to work for London Clearing House (LCH). When he became available, we offered him the position of CEO at ECX. Patrick's eloquence and charisma made him an excellent salesman. He was very clinical about business and could speak his mind and assert his opinions candidly—a quality that came in extremely handy a short while later. He also continued the tradition of relentless marketing throughout the continent. Patrick and his team were constantly on the road.

Patrick's first challenge came with our intention to launch a CER futures contract. By 2008, the necessary conditions and infrastructure for a CER futures market were in place and we were keen to establish a lead. ECX, however, needed LCH's cooperation as its clearinghouse to list a CER contract. Under our current contract, ICE was our technology and regulatory services provider and we shared LCH as our clearinghouse. However, ICE announced that it was moving the open interest on the exchange to its own clearinghouse, ICE Clear Europe. LCH wasn't amused at the prospect of one of its largest customers forming its own clearinghouse. This led to LCH's refusal to clear any new ICE products, including our allowance futures contract. They didn't want to lavish additional resources on a client who would soon disappear.

By this time, I had already resigned from the ICE board in order to pursue the interests of CLE.17 Even if I remained, my status as an independent director was eliminated. As a customer, ECX had diminished input in ICE's decision to move its clearing operations. If another exchange were to list the CER contract, CLE's very existence could be threatened if another exchange gained a foothold in the space. After endless personal pleas and letters, LCH refused to budge. Convinced that we had the law on our side, Patrick urged us to take LCH to court—a decision that the ICE board of directors agreed with. The United States was a very litigious country and its lawsuits were often frivolous. The same could not be said about the United Kingdom. We hired a Queen's Counsel18 to represent us, and a week before the trial, LCH finally relented and agreed to clear the contract. ECX listed the CER contract, and our hegemony of the emissions trading space continued.

Patrick built his team carefully and made sure that our ECX offices were physically separate from the rest of CLE. He wanted to establish the exchange as an entity that was separate from the holding company, and his team appreciated the newfound privacy and identity. It was important for the image of the exchange and helped Patrick market our products. The exchange's trading volume and open interest reflected his hard work. Over the course of the next two years, our volume went from 1,037,000 tons at the end of 2007 to 2,831,000 by the end of 2008. It further climbed to 5,122,183 tons by the end of 2009. By this time, ECX had consistently held more than 85 percent of the EU market share among seven odd exchanges competing in the space. The overall market was maturing as well. Given the total allocation in the EU ETS was about 2 billion tons, ECX volume alone indicated that the market was beginning to turn over multiple times.

Volume continued to grow during the first half of 2010, and ECX became a formidable force in the exchange world. The future was as bright as ever. The open interest of the new allowance contracts eventually exceeded that of Brent Crude oil, and carbon emerged as the single largest commodity in Europe as measured by open interest. As of August 26, 2010, combined open interest in ECX CER and EUA futures and options contracts surpassed one billion tons for the first time and stood at 1,035,091 contracts. This was a large number compared to the 852,971 in open interest for Brent Crude that same day.19

There were some minor technical obstacles that had to be overcome. Almost all of the volume was concentrated in the current December contract. There was some trading in the March contract because the compliance of the previous years had to be achieved and reported by April. The June and September contracts hardly traded at all. The companies were able to hedge their compliance needs until 2012. However, the efficacy of the hedges would have been improved if the hedges were more coincidental with the contracts that were listed. Companies faced unnecessary basis risk as a result. Additionally, despite the lack of certainty regarding the continuation of emissions trading in the European Union after 2012, open interest continued to grow.

We continued to innovate, adding CER options and futures contracts with expirations from 2013 to 2020—past the initial Kyoto compliance period—because there was a market demand for it. We believed that the market would welcome these deferred contracts, and it did. The market was sending an implicit message about the expectations and needs of the European industrial community. Policy makers took note of this, and the confidence shown by the markets was widely publicized.

One successful innovation led to a chain reaction of other innovations. We introduced a one-day futures contract to compete with Bluenext, which dominated the spot market for EUAs. We also signed an agreement with XShares to design and market the world's first exchange-traded fund (ETF) for carbon, named the AirShares Carbon Fund, which began trading in December 2008. This was a failure because of regulatory issues and uncertainty regarding the economic value of the product, which was derived from EUAs and CERs.

The Economic Value of an Exchange

I had previously spoken about the value of exchanges in price discovery, hedging, and providing an alternative market for the purchase and sale of allowances. I will leave it to others to determine the value of hedging and the value of price discovery, and focus solely on the economic value of the exchange, as demonstrated by ECX. It is also a story of reduced transaction costs.

The same exercise we did for SO2 allowances can be applied to EUAs as well. The initial bid-offer spread on the exchange was between €0.20 and €0.25. By the end of 2010, it had narrowed to about €0.02. Assuming a €0.20 difference and the fact that 5 billion tonnes were transferred in the spot market, there was approximately a €1 billion value in savings to the participants in 2010 alone in the spot market. ECX witnessed the delivery of 165 million tonnes. Assuming no fees by the exchange and a $20 OTC brokerage fee per contract, or about €0.14 per tonne, the cost savings enabled by the exchange amounted to €30.7 million.20

The EUA futures contract, like the SO2 futures and interest rate futures contracts before it, was an example of a good derivative.

Reflections on the Success of ECX

The EU ETS had been a dramatic success, and so had ECX. According to A. Denny Ellerman from the MIT Sloan School of Management, “The ability to use CERs and ERUs for compliance in the EU ETS has made the price of EUAs the reference price for the world carbon market.”21 ECX had become the benchmark exchange for carbon prices. The reasons behind the success of the scheme can be traced back to public policy in the European Union. Environmental markets work where there is legal and regulatory clarity. In this case, clear and unambiguous property rights were mandated and reinforced by the Kyoto Protocol. The consummation of the Protocol also drove the EU to move forward with a voluntary pilot program. In particular, the program succeeded because it was supported by the consensus that had been built between the EU member states, sovereign governments, and industry sectors. When the United Kingdom and Denmark started their own voluntary pilot programs, most companies felt that the scale of these efforts were too small and did not convey the urgency to learn about emissions trading. With the launch of the mandatory EU ETS, however, these multinational efforts gained more gravitas, and were able to reinforce the validity of voluntary programs like ECX.

Like ECX, CCX was a pilot program that achieved all of its objectives as a proof of concept. It facilitated hedging, price discovery, and created an alternative place to make and take delivery of allowances. Unlike ECX, however, CCX lacked an enabling legislation. Why climate legislation never passed in the United States is a subject of much speculation, and is a tale in and of itself. In the end, the worldwide price of carbon remained determined by the supply and demand for allowances and CERs on ECX.

The Acid Rain Program of 1990, coupled with the implementation skills of the EPA, facilitated the proliferation of an OTC market in SO2 and NOx, and subsequently the emergence of a successful and transparent market for both types of emissions. This ultimately dissolved because the government failed to provide legal certainty regarding the extension of the Clean Air Act. Instead of using market-based cap-and-trade, our federal government turned to traditional command-and-control. It is interesting to recall that during the days of negotiating Kyoto, it was the United States that led the efforts to introduce emissions trading as a viable tool. The Europeans were skeptical of the idea and opposed it. How the tables turned. Europe became the leader in market-based policy tools, while the United States became the champion of the reverse. The lessons learned in both Europe and the United States can provide valuable insight when implementing environmental policies in emerging countries like India and China.

Letting Go

I visited London frequently to update shareholders and attend board meetings for the Climate Exchange. In spite of the stellar performance of ECX, our stock had been laboring. We were under some pressure to hold a liquidity event by some of our investors. Some investors had large positions and couldn't sell them easily without driving the price of the stock lower. If the exchange were sold, all of their shares would sell at the same price. ICE was the natural purchaser because it knew our business intimately and because of our original contract with them. In fact, we had considered selling the company just before the financial crisis, but were not successful. Now was the time to actively pursue a sale. I had been in constant contact with Jeff Sprecher over the last few years. ICE had bought a 5 percent stake in CLE at a price of £6.5 in 2009. I consulted with Neil, our CFO Matthew Whittell, and the board, and all favored this decision.

ICE and CLE both retained investment bankers. The last hurdle for CLE was to sell the company at the highest possible price. We formed a board committee to oversee the negotiations. Brian Williamson chaired the committee since he was armed with his prior experience in selling Liffe. Sir Laurie Magnus, an investment banker who specialized in insurance, chaired the audit committee. Detail-oriented and extraordinarily competent, Sir Laurie won my favor the moment I met him. We hired JPMorgan to represent us. We also retained Gavin Kelly, a savvy and tough negotiator who was always up for a fight and had done a great job representing CCX. He became our banker when we sold CCX to the reorganized Climate Exchange PLC in 2006. Gavin was Scottish and reminded me of Hamish Campbell in the 1995 film Braveheart—the brave childhood friend who had fought with William Wallace to free Scotland. After a four-month period of negotiations and due diligence, we finally agreed to sell CLE to ICE. There was one condition. CCX members, myself included, would be allowed to help with the transition of ownership. Accordingly, I happily agreed to work with ICE until the end of 2010. The final price of the sale was at £7.5 per share, at a 57 percent premium to where the shares were trading. This equated to a value of $604 million.22 Much of that value was attributable to ECX. To put this in perspective, the NYSE was valued at $5 billion. This meant that CCX was worth close to one-eighth of the world's largest stock exchange, and this was even without regulatory uncertainty. It was indicative of the value of emissions markets.

I had grown emotionally attached to CCX and emissions trading during the past 20 years. I never intended to sell the company. After all, this was a lifetime bet I had taken. My feelings were obviously mixed, but I had no choice. We called our original investors and thanked them individually for their support. I saved the best for last and made a call to Father Francis. We promised to stay in touch. CLE had literally been a blessing to its stockholders, exchange members, participants, and the management teams on both sides of the Atlantic. ECX had since continued to be the preeminent emissions exchange in the world.

In the meantime, other stories of climate exchanges were unfolding in China and India.

1Thomas Ward, “England's Reformation,” 1688.

2Adapted from Sigurd Lauge Pedersen, “The Danish CO2 Emissions Trading System,” Review of European Community and International Environmental Law 9, no. 3 (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 2000).

3Ibid.

4“Framework for the UK Emissions Trading Scheme,” UK Department for Environmental, Food and Rural Affairs, 2001.

5“Appraisal of Years 1–4 of the UK Emissions Trading Scheme,” Report by ENVIROS Consulting commissioned for the UK Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, December 2006.

6Gerry Hueston, “Beyond Petroleum—Learning to Achieve Prosperity through Sustainability,” West Australian Business Leaders Breakfast, Perth, West Autralia, August 3, 2005.

7David G. Victor and Josh C. House, “BP's Emission Trading System,” Energy Policy 34 (2006): 2100–2112.

8On the Dutch program, see A. M. Sholtz, B. Van Amburg, and V. K. Wochnick, “An Enhanced Rate-Based Emission Trading Program for NOx: The Dutch Model,” Scientific World Journal 1, Suppl 2 (2001): 984–993. On the Norwegian program, see Royal Norwegian Ministry of the Environment, “The Norwegian Emissions Trading System,” presentation to ICAO Workshop: Aviation and Carbon Markets, Montreal, June 18, 2008.

9“Green Paper on Greenhouse Gas Emissions within the European Union,” Commission of the European Communities, Brussels, August 3, 2000.

10Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of October 13, 2003: “Establishing a Scheme for GHG Emission Allowance Trading within the Community and Amending Council,” Director 96/61/EC, Official Journal of the European Union, October 25, 2003.

11Lodewijk Petram, “The World's First Stock Exchange: How the Amsterdam Market for Dutch East India Company Shares Became a Modern Securities Market, 1602–1700” (dissertation, University of Amsterdam, January 28, 2011).

12The trade was cleared by Calyon Financial SNC (a subsidiary of Calyon Corporate and Investment Bank) and ABN AMRO Futures Limited. “Trading Starts in First Carbon Futures Contracts,” Press Release, ICE, April 22, 2005.

13Matthew Saltmarsh, “Market for Emissions Picks Up Steam as Kyoto Protocol Takes Hold,” International Herald Tribune, July 6, 2005, 19; Kevin Morrison, “Climate Exchange in the Black,” Financial Times, October 1, 2005, 16; Richard Orange, “Tonnes of Trouble for EU on Pollution,” The Business, January 9, 2005; Deborah Kimbell, “Euro Carbon Trading Graduates to Cash Settlement,” Euromoney, February 2005, 24.

14“SGI-Orbeo Carbon Credit Index,” Société Générate Index, February 2008.

15“Question Marks over EU CO2 Trading Scheme,” EurActiv, June 29, 2007.

16Steven Mufson, “Europe's Problems Color U.S. Plans to Curb Carbon Gases,” Washington Post, April 9, 2007.

17I was a director at Intercontinental Exchange, Inc. from November 2002 to March 2008.

18A Queen's Counsel is a lawyer who has been appointed by the Crown in the Commonwealth to wear a silk gown and take precedence over the other lawyers in court. This honor is bestowed only upon on those have practiced law for at least 10 years.

19“As of August 26, 2010, combined open interest in the ECX CER and EUA futures and options contracts surpassed 1 billion tonnes for the first time and stood at 1,035,091 contracts. Compare this with 852,971 in open interest for Brent Crude that same day.” Data taken from “ICE Daily Volume and Open Interest Records: ECX,” Commodities Now, August 26, 2010, and “Daily Volumes for ICE Brent Crude Futures,” ICE, August 26, 2010.

201,000 tonnes per contract. Using a 1.18608 exchange rate from December 2005, $20 per contract roughly equals €16.86 per contract. Thus, (€0.20 – €16.86/1000) × (165,000,000) = €30,217,726, or €30.2 million saved. For purposes of simplification, assume no fees by the exchange or other transaction costs.

21A. Denny Ellerman, Frank J. Convery, Christian de Perthuis, and Emilie Alberola, Pricing Carbon: The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

22“Intercontinental Exchange Announces Acquisition of Climate Exchange,” ICE, Press Release, April 30, 2010.