Chapter 23

India

A Promising Beginning

The earth, the air, the land, and the water

Are not an inheritance from our forefathers

But a loan from our children.

—Mahatma Gandhi

Centennial Hall was a nondescript, red-brick building on Delaware Street in Minneapolis. As a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, I used to live on the sixth floor, which was reserved for international graduate students. While unpacking on my first day there, I left the door open and hoped that another graduate student would stumble by and say hello. Nobody did.

The room was small and felt solitary, so I wandered to the dining room in the basement, hoping to enjoy a good meal. The food was served cafeteria-style and was very bland. Another disappointment.

I journeyed back to my room. The sixth floor was now filled with students moving into their rooms and milling around in the hallway. The floor turned out to be an international cornucopia of culture, with students from the United States living alongside others from Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. It was there that I met my Indian friend, Sanjib Mukherji. He carried himself with great elegance. He was somewhat soft-spoken and shy, but this did not conceal his regal bearing. We quickly became friends, and therein began my real education of the Indian subcontinent.

Brahmins and Katyas

My picture of India had been framed by early childhood memories of American-made movies like the 1942 film adaption of Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book, an action and adventure film about an Indian boy, Mowgli, who was raised by wolves. The vivid prose evoked beautiful imagery and excited my imagination. I was Mowgli. I shared his victories in fighting tigers and taming cobras. I also felt his pain as an outsider when he left the wolves to live among human civilization. I always thought, with childish innocence, “Someday I will go to India.” I later saw Richard Attenborough's 1982 film, Gandhi, which anchored my desire to see India. Gandhi's public life was also chronicled by the photographer Margaret Bourke White. I discovered the original portrait of Gandhi by her that was used for the cover of Time magazine in 1948. It proudly sits in my study to this day.

Sanjib was from Kolkata and proud of his Bengali language and culture. He was a Brahmin but had the common touch. We spent endless entertaining evenings with his friends who were either Brahmins1 or Katyas. In spite of their upper-class upbringing, they were all sympathetic to the tapestry that was India. They felt empathy for the untouchables, pride for the business class of Banias,2 affection and understanding for the Muslims living in India, and respect for the Parsees. I learned about prejudice from Sanjib's Anglo-Indian friend, who was often cast out of social circles because of his half-English, half-Indian heritage.

There were no authentic Indian restaurants in the Twin Cities at that time. To my great delight, Sanjib and his Indian roommates had learned to cook for themselves. They taught Ellen how to make a wicked curried chicken dish that we enjoy to this day. I was amazed that Indian food could be made without prepackaged curry powder. I lost touch with Sanjib after graduate school, but I often wondered how he was doing.

I thought of him as the plane landed in New Delhi, India, in 1991. Arif Inayatullah, one of my colleagues at Banque Indosuez, had invited Ellen and me to his wedding in Lahore, Pakistan. We decided to spend some time in India before heading to the wedding.

It was the start of an exciting time in India. The country had just begun the process of economic liberalization under the leadership of Dr. Manmohan Singh, a PhD economist who was then India's finance minister, and now its prime minister. Many years later, the positive impact of these reforms would hit the commodities market, helping me realize my dream of doing business in India.

The two days we spent there felt more like an appetizer in a seven-course meal. Being in India was like an attack on all our bodily senses. We visually devoured the Taj Mahal, tasted the tantalizing spices of Indian cuisine, heard the constant rhythm of honking in the streets and felt the subtropical heat almost charring our skins.

Riding around Delhi with Ellen in a phut-phut,3 I could feel the energy that was India stirring in the air. Forty-four years after leaving its colonial past, India had the ninth-largest economy in the world by GDP purchasing power parity4 and was on the verge of economic liberalization.5 India seemed ready for a change. My thoughts were interrupted when a gust of black soot from a street bus hit Ellen and me straight in the face. Pollution was rampant in India.

Without standards for emissions, waste disposal, or water treatment, heavy pollution took its toll on the health and prosperity of India. The World Bank estimated that total environmental damage amounted to $10 billion, or 4.5 percent, of GDP in 1992. Of the total, urban air pollution and water degradation accounted for $7 billion in damages alone.6 Air pollution caused 500,000 premature deaths and 3 to 4 million new cases of chronic bronchitis in 1992.7 Of 3,119 towns and cities, only 217 had wastewater treatment facilities.8 With 70 percent of available water polluted, more than one million children died of gastrointestinal diseases in the 1990s.9

There must be something the markets could do to help, I thought.

As we left the country, I entertained the idea that the aspirations of a billion Indians had the power to positively transform the country. I was determined to come back under a different banner. Ellen and I went to Lahore for a magnificent three-day wedding before returning to the United States.

India continued to change dramatically in the following 12 years. Its software industry was booming, and the bureaucracy responsible for hindering economic growth during Sanjib's time was now showing slow signs of decay. Change was also afoot in the financial sector. In 2002, the government of India permitted futures trading on a national basis and relaxed many other rules in its commodities regulatory act. This was highly significant given that, prior to this, there had only been regional spot markets regulated at the state level.

India had a long and checkered history with trading. Its rich agricultural commodity base made it an important stop along the Silk Road. The Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British later landed on its shores with more than just trading in mind. The cotton trade association in Mumbai commenced futures trading in 1875, not long after futures trading began at the CBOT. Bullion, jute, and wheat trading were introduced shortly thereafter.10 However, years of bureaucracy and fear over speculation and its impact on farmers limited trading to regional spot markets. Following the reforms to the Indian Commodities Act,11 three new national exchanges were established in 2002 and 2003.12 As part of its efforts to educate and build relations with Indian futures market policy makers and businessmen, the USAID hosted a trip by an Indian delegation to New York, Washington, DC, and Chicago in 2004 to learn more about the U.S. futures exchanges.

CCX hosted a seminar on emissions trading in our offices for the USAID mission. One of the attendees from the Multi-Commodity Exchange (MCX) came back later that afternoon to discuss a linkage. We agreed to speak in the future. After numerous telephone conversations and e-mails, we agreed to license a mini-size European Union Allowance contract to MCX in 2006.13 This was done to ensure better local price discovery of carbon credits for the growing Indian CDM market besides helping the participants cover the risks associated with selling and buying of carbon credits. I hoped that it would lead to a CCX-type market in India.

The MCX contract on EUAs failed to attract any speculative interest and was dead on arrival. It was simply too far ahead of its time. The Indian Commodity Exchange Act still did not recognize intangibles, such as carbon permits, as a commodity. I recalled my efforts with Phil Johnson in redefining commodities when interest rate futures were first launched in the United States. History seemed to be repeating itself. After much back and forth with the regulators, we ultimately decided to change the contract to a cash-settled instrument, but it, too, failed to gain any traction. I intended to start a market similar to CCX in India, but had to be patient. A platform had yet to emerge to promote the activities of CCX, ECX, and the CCFE in India. Thankfully, it arrived quicker than I expected.

Building Interest for Offsets

Rajendra “Pachy” Pachuri, my friend of 10 years, the head of The Energy Research Institute (TERI)14 and the chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), organized a summit in New Delhi, called the Delhi Sustainable Development Summit (DSDS) in 2006. The event has since become one of the globally preeminent sustainable summits. Pachy and I had met at a number of meetings over the years in New York, Washington, DC, and London. He was a true citizen of the world. His commitment to the environment in general, and India in particular, was inspiring. Very few people could be as passionate about their goals and still be reasonable in their approach, and for that reason, Pachy and I readily understood each other.

On February 1, 2006, Pachy invited me to deliver a keynote speech and participate on a panel for a greenhouse gas forum held by the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) in New Delhi.15 There was also a CEO forum the day before the summit that I was asked to participate in. The timing was perfect, but it was a logistical nightmare, as I also accepted an invitation to speak at a two-day Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia (CLSA) conference in Tokyo that was scheduled to start on February 6.

Nevertheless, I decided to give the keynote speech on the morning of February 1, take a 6:50 A.M. flight the next day to Mumbai, and fly back to Delhi that evening to speak at the panel the next morning. The following day, I would fly to Tokyo via Bangkok for the CLSA conference. The planning of the itinerary had to be seamless, as every moment of this trip had to be used effectively.

The key was to remain energized at all times, even after flying for an entire day. I followed a routine that worked for me. My flight from Chicago to India was on a Sunday, and I arrived in Delhi on a Tuesday morning. After checking in at the Taj Mahal hotel, I spent an hour on the treadmill and met Murali Kanakasabai at the hotel lobby. Together, we toured art galleries and museums to relax and learned about the historical and contemporary art scene. I was on the Board of the International Center for Photography and they had referred me to a local artist. Her unavailability disappointed me, but there were so much else to see. At the end of the day, Murali and I went back to the hotel for dinner. The hotel was one of those modern edifices with an opulent lobby. It had very little local color except for its authentic restaurants. The highlight of the day was having chicken chettinad for dinner. It was a fiery spicy southern Indian dish that Murali had recommended. It has since become my favorite.

The next morning, I gave the keynote speech at the Indian Habitat Centre. The Centre was like an academic campus and I felt at home. It was a beautiful brick building, built to promote awareness in environmental issues like energy conservation and water, air, noise, and waste pollution. It was a fitting location for the event. After describing the successes of CCX and ECX, I floated the idea of the India Climate Exchange (ICX). The vision was for ICX to be a voluntary cap-and-trade program for Indians, designed by Indians, and made compatible with India's development needs. I knew that developing economies like India were foremost concerned about economic growth, so my environmental solution had to be fine-tuned to support this important goal.

I stressed that CO2 emissions would initially grow modestly for some period of time before any reductions could be observed. This was analogous to the emissions targets in Ireland and Portugal under the EU ETS. The initial period of the proposed program allowed for learning by doing and would help the Indian industry adapt by building capacity among Indian corporations.

The CCX offset model also provided guidance for how we might approach a similar program in a developing country like India. The country had a large rural base that depended on agriculture and rural industry for livelihood. Gandhi was absolutely right when he said, “India lives in its villages.” A billion people depended on this rural population for their food security, so concerns about agriculture and rural development were high among Indians. I explained that by linking the ICX carbon market with specific offset programs in India, we could create a catalyst for economic development, especially in rural areas. Furthermore, by supporting rural projects, Indian corporations would be able to bring about visible transformations in India's villages. This was my vision and I was anxious to learn how my audience would respond to it. The audience welcomed my ideas and the Q&A session was lively.

Next was a meeting with the chairman and managing director of BASF India, the Indian branch of the largest chemical company in the world. He shared my feelings about the cost of pesticides and their financial and personal impact on India's cotton farmers. Many farmers who could not pay back the loans they took out to buy pesticides committed suicide. As a large producer of pesticides, BASF was concerned about this not just as a business issue but a social issue as well. Since BASF served the agricultural sector, it was interested in our offsets program and wanted to know how it could help India's farming community. BASF units in Europe were participating in the EU ETS program, and he suspected that the firm's senior management in Germany would want the Indian branch to become involved. BASF joined the ICX advisory committee and I was elated. Our next meeting reinforced my beliefs about India's development.

The chairman of Ranbaxy, an Indian pharmaceutical company, had reserved a small conference room in the Oberoi hotel for our scheduled meeting. The room felt more like a study, and the setting was intimate. He explained to me that Ranbaxy was a low-cost manufacturer of generic drugs. The firm's business model entailed using the profits from these generic drugs to develop new drugs.

“We have over 300 PhDs doing research,” he said matter-of-factly. “My hope is for us to become a world-class pharmaceutical company that competes with American and European companies. We're already getting FDA approval for some of our drugs, which will gradually be introduced in the U.S. markets. India has the education system in place to achieve this. Our population is also much younger than China's.”

India had the potential to become a major economic powerhouse—a country that had transformed from the one that Sanjib lived in. I was convinced that ICX would be the first cap-and-trade market in Asia. To do this, I knew from my previous experience that I had to start with educating and capacity building. Not just with the trading community but with corporations, government, and the general public. For new markets to survive, I knew the complete system of institutional infrastructure had to be activated. The rest of the day was spent networking and attending a dinner addressed by the Minister of Finance. It was the start of a new journey and I knew it was going to be a fun ride.

The next day to be spent in Mumbai was packed with meetings with corporates. We arrived in Mumbai only to find out that the airport workers were on strike. We were welcomed by piles of garbage and placard-carrying workers on the airport premises. We were told that traffic could be blocked and I wondered if we could make all the meetings on time. The meetings had been scheduled after weeks of painstaking preparatory work and late-night telephone calls by Rafael Marques and Murali. I could not miss any of them.

Murali had scheduled eight separate meetings in different areas of Mumbai, so we had to traverse the city twice. The trip from one side of the city to the other took as long as 90 minutes on a normal day, but on that day it took much longer. As we rushed between the city's extremities, I couldn't help but notice the stark contrast around us. Tall skyscrapers, proudly conquering Mumbai's skies, stood side-by-side with tin-roofed slums. The latest luxury cars competed for space with noisy motorized rickshaws and street hawkers. Every available space seemed to be thriving with small retail businesses. There are 210 million people living below the poverty line in India. This exceeds the U.S. population of 309 million.16 Mumbai represented this duality clearly. Nonetheless, one unmistakable fact was that the city was bustling with energy.

We headed for our last meeting with Mukesh Ambani, CEO of Reliance Industries, one of India's largest conglomerates. The headquarters of the company was in the southern end of Mumbai called Nariman Point, a place with some of the highest-valued real estate in the world. Murali and I had not had time to eat any breakfast or lunch and the novelty of trafficking through the streets was gradually wearing off.

Although we could see Maker Chambers, the headquarters of the company, we were told that we would be half an hour late because of the traffic. I suggested that we get out of the car and literally run to be on time. What a sight we must have been, walking across the main thoroughfare and then running through the side streets. We arrived one minute early for our 4 P.M. appointment. I leaned over and said, “Murali, never be late to meet a CEO.” He smiled.

The Mumbai monsoon had left visible marks on the building. It looked shabby from the outside, but the inside was another world. The offices were sleek and modern. Mukesh Ambani was a man with a friendly demeanor who didn't wear his success on his shoulders. He had his entire senior management team for the meeting. He listened attentively and when he didn't understand something, he probed us gently for more information.

After my pitch, he said decisively, “Reliance is interested in participating in the CCX offsets program and I want to be part of the ICX design program.” He was one of the richest and most powerful businessmen in India and his imprimatur meant a lot to us. I became more convinced that ICX was a reality in the making. Murali and I flew back to Delhi that evening, exhausted but pleased with our productive day.

My vision for CCX in India was beginning to take shape. We would take a threefold approach. First, I believed that the CCX offsets program could be expanded by including projects from India. The fruits of the carbon market had to trickle down to the grassroots. Second, we should develop a framework for a transparent and regulated means of transacting CERs for India. The CDM sector in India was growing but lacked an open market framework. The third approach was my most ambitious one: to develop the India Climate Exchange. ICX would enable Indian corporations to determine the most cost-effective greenhouse gas mitigation measures, and lead to new products, markets, profit centers, and social development opportunities.

I left Delhi that night, laid over in Bangkok, and then proceeded to Tokyo. I was starting to feel like a lounge act by the end of the trip. Meetings and more meetings. Speeches and more speeches. My father would have been proud of me. I was sad that he wasn't at home awaiting my stories of the trip.

ICX Is Conceived

In August 2006, we signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU)17 with TERI to develop an offset program tailored specifically for India.18 As part of the arrangement, TERI would lend its technical expertise in building India-specific offset protocols and CCX would link its market to Indian offsets.

At the same time, we decided to develop and trademark the India Climate Exchange (ICX), the first pilot greenhouse gas emissions trading program in India. It was a great opportunity to bolster sustainable development efforts in rural India while expanding the offset market for carbon emissions.

Replicating the framework that worked for us with CCX, we began to actively recruit members for the ICX technical design committee and advisory board. Pachy agreed to serve as honorary chairman of the advisory board.19 Other board members included Deepak Chopra, chairman of the Chopra Center for Wellbeing, and Jonathan Lash, president of the World Resources Institute. I made two more trips back to India by myself, while the other members of CCX went separately to recruit new members.

The ICX technical advisory committee was the heart and soul of the ICX program. They were charged with designing the emission goals, program time line, sectors to be included, and numerous other criteria that formed the skeleton of the market. We were anxious to have a wide diversity of participants in the committee. This had proved invaluable in the CCX formation process and was critical to our success.

Charged with recruiting members for the ICX technical committee, I relied on Murali, Rafael, and Mike to market the idea. They made numerous trips to India. I knew we had to get the big conglomerates in India to add credibility to the program. Among the big corporations in India were Reliance Industries, Tata Group, Godrej, Bajaj, and the ADAG group. The team was having a roller-coaster ride with recruitment, but I encouraged them to stay persistent.

Despite my excellent meeting with Mr. Mukesh Ambani in Mumbai, Reliance had still not signed on to the ICX committee. This was somewhat understandable, given that Reliance was a huge corporation and everything they did was closely monitored. Their main operations were also centered around petrochemicals and refining, both of which generated high emissions. Getting Reliance on board would be huge, and I urged Murali to focus on them.

The breakthrough came early one morning. Murali had been trying to reach the senior vice president at Reliance all evening but was unable to get through. He finally made the connection at 3 A.M. Chicago time, which was around 1:30 P.M. in Mumbai. Surprised, the senior vice president inquired if Murali was calling from an airport in Europe. When Murali responded negatively he exclaimed, “Why are you calling me at 3 A.M. your time?” Murali politely responded, “Because my CEO has been up all night sending emails requesting the status of Reliance in ICX. Sir, your joining us is very important to make this successful.” Reliance's commitment letter came in the next day. Our persistence had paid off once again.

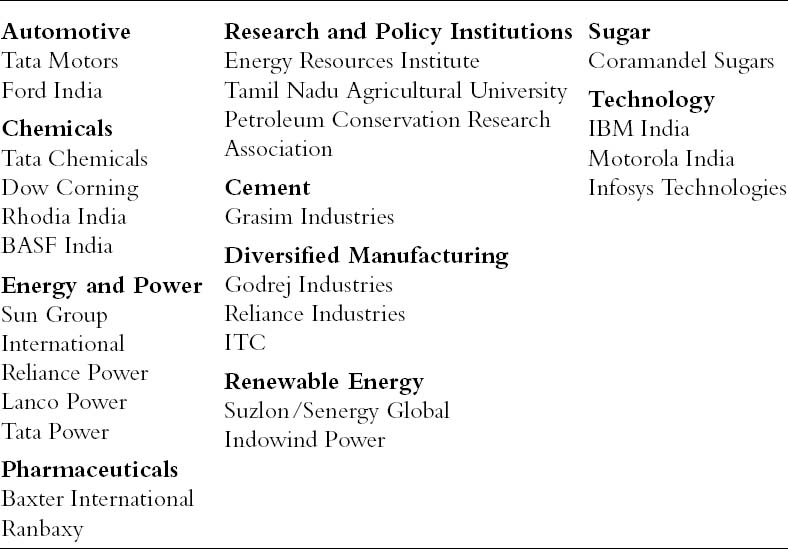

After several other efforts in India, we managed to recruit 24 top Indian companies and universities to be part of the ICX technical committee. It was a diverse group of corporations, similar to the makeup of the CCX technical committees. Members of the ICX technical committee included Tata Motors, Reliance Industries, Lanco Power, Reliance Power, and Infosys, among others. The committee met on four different occasions to participate in the drafting of what came to be called the Mumbai Accord.

The ICX technical advisory committee held its first meeting in January 2007 at the Hotel Shangri La in New Delhi, coinciding with the 2007 Delhi Sustainable Development Summit, where I gave a keynote speech. After providing some welcoming remarks, I outlined the consensus-building process that the CCX design committee had taken. I gave an overview of the state of environmental markets and stressed the importance of Indian corporations to participate in the process, particularly given India's role as a leading player supplying offsets under the Clean Development Mechanism protocol.

Table 23.1 ICX Preliminary Draft of Term Sheet

| Greenhouse gases included | Entity-wide emissions CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, PFCs, HFCs, SF6 from major emitting activities in India. Members include direct (combustion) emissions plus indirect (from electricity, steam, and cooled-water purchases) emissions from major emitting activities. |

| Emissions quantification | All emissions to be quantified using agreed-upon standard methods and subject to independent audit. |

| Annual true-up | Subsequent to each year, each source must surrender instruments in an amount equal to the emissions occurring during that year. |

| Emission baseline | Annual emissions during the year 2006. |

| Emission reduction objective | Calendar year 2010: 112% of baseline Calendar year 2011: 115% of baseline Calendar years 2012 to 2020: 118% of baseline |

| Economic growth provision | Maximum required total purchase of emission allowances and/or offsets is limited to: 3% of an emitter's baseline during 2010 and 2011 4% of baseline in 2012 and 2013 5% of baseline in years 2014 and 2015 6% of baseline in years 2016 through 2020 |

| Eligible project-based offsets | India-specific protocols to be developed |

| Registry, electronic trading platform | Registry will serve as official holder and transfer mechanism, and is linked with the electronic trading platform on which all trades occur. |

| Exchange governance | Self-regulatory organization overseen by committees composed of exchange members. |

As we suspected, the big concern was how to handle growth and which emissions to include. At the time, India was growing at an average annual rate of about 4.5 percent and accounting for total greenhouse gas emissions of about 1.8 billion metric tons. Many of the big Indian corporations had started to diversify across multiple sectors. Indeed, Murali joked that you could go through an entire set of daily activities just by using Godrej's products. They made everything from bath soap to storage cabinets to ceiling fans, coolers, and even door locks. Some of these sectors were new and fast growing, which meant that their emissions growth could be enormous in initial years before stabilizing. We were compelled to include all corporate emissions so as to avoid cherry picking the best locations, and knew that we had to design sufficient provisions to manage this. Following the CCX concept, we decided that an economic growth provision would cap the maximum liability for any increases in carbon emissions beyond a certain point. This was designed as a safety valve to avoid hindering economic growth among member companies.

Table 23.1 is the preliminary draft of the ICX term sheet.

The Andhyodaya—A Chain Reaction of Innovation

As we were putting together the bricks to build ICX, our early efforts on the offset side were already bearing fruit. More than 150 offset providers were linked to the CCX markets directly or through their aggregators. By 2008, India was the largest international supplier to offsets in the CCX market.

While this made great business sense, I was always amazed by what the markets could do to help those at the grassroots level. The greatest attribute of the carbon markets was its ability to promote economic development. This was especially true in the poorest parts of the world. The Andhyodaya, the first member of the CCX program from India, demonstrated this point clearly.

I met with the executive director of the Andhyodaya during my first trip to India at Murali's suggestion. An NGO based in the Ernakulam district of Kerala, South India, the Andhyodaya specialized in small-scale biogas, solar energy, and rainwater harvesting.

In January 2007, the organization decided to join CCX as an aggregator of carbon emissions offset credits for small farmers with microdi-gesters.20 The credits were generated from sustainable development and renewable energy projects across rural India and sold on the CCX.

We began our collaboration to develop a technical protocol to credit biogas from rural households. The biodigestion process was simple. Animal waste was put in a cylindrical container that resembled a garbage can. The waste was fermented in a sealed container without oxygen. Anaerobic digestion produced methane gas, which rose to the top of the container. Captured gas was transported to a farmhouse by tube, and could be used for cooking purposes.

The small farmers would receive offset credits of about four tons annually per biogas unit, and these were to be sold on CCX for about $4 to $5 per ton. As a result of this offset program, the average farmer made about $20. Since the average family income in this region was less than $1 a day, this was a substantial amount relative to their total income. There were numerous additional benefits to this program. The captured methane gas would replace wood as fuel, allowing young girls the opportunity to go to school instead of foraging for wood every day. The burning of wood indoors caused a number of lung problems that could be reduced if gas was used instead. CCX already had an established protocol for agricultural digesters, which was a useful model for developing protocols for biogas in India.

CCX ended up running into many unexpected complications. The Indian biogas units were tiny compared to North American ones, scattered in remote rural areas that were difficult to access, and were operated by mostly simple farmers. The cost of monitoring and verification many hundreds of units over inaccessible terrain was astronomical, so we decided to resort to statistical sampling—a technique that was well accepted in industries like semiconductors and airlines but not, at the time, prevalent with the United Nations CDM protocols. The United Nations did eventually come to embrace statistical sampling.

We were met with another obstacle: How could we teach people with little or no education the details of a technical protocol? To succeed, we had to build a protocol that took into consideration the local situation and resources. This required us to work alongside local villagers, NGOs, and technical institutes in India.

The complications were all not external. The CCX offsets committee had never heard of small-scale biogas units, nor did they understand what made sense in rural India. They demanded that we have meters measuring the amount of methane generated at each biogas unit. The cost of doing so would have killed the program. We explained to the committee that the Indian biogas units did not and could not enjoy the economies of scale of their larger U.S. counterparts. To further convince them, we designed a cluster-sampling procedure that took into consideration the geography, size, and number of units. The method grouped the biogas units by their characteristics, and samples were drawn from each of these groups in order to approximate the amount of methane generated by biogas units with similar characteristics. This eliminated the cost of having to measure the amount of methane generated at each biogas unit individually.

After addressing these issues, we finally had a product that was locally relevant and scientifically justifiable. The real work had just begun. When our NGO partner proudly took the program to the people, they were bombarded with all sorts of questions. No one understood what global warming was or what they were supposed to sell. The people laughed at the thought of selling “smelly air” from Kerala all the way to the United States. Local papers branded the program as a big scam. Everyone questioned the motives of the NGO and its new U.S. partners.

In spite of these obstacles, we prevailed through persistence and constant education. The first trade was consummated in 2008, during an event hosted by the Delhi Sustainable Development Summit (DSDS). The small-scale biogas projects had led to cuts equivalent to 40,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide. This represents a market value of approximately €123,000 or $160,000. A huge event was held in Kerala to distribute the first CCX checks. The whole event was decorated like a local wedding, with all the women and children wearing their brightest saris and biggest smiles. After the celebrations, many of the rural participants invited the CCX team to have dinner with them. We did not know their language nor did we know any of them personally, but the program and its success provided the connection. One of them said to Murali, “We've had several organizations that have given checks to us for charity, sometimes bigger than this one. But I am so proud of getting this one because I earned it. We are both partners in solving the sins of industrialization.” I was so proud of our team.

The program started with 3,000 families in one state and expanded to more than 100,000 rural poor families in two states. A year or so later, I was told that the carbon program was paying for all the biogas plants to be insured. Not only that, a local bank had started to issue carbon vouchers to the villagers wherein they could exchange the voucher for cash equivalents in any of their bank branches. The seed of innovation we had sown was growing organically. The villagers were now managing their risk and reducing transaction costs through their own resources.

We were successful due to several reasons. Our intervention was bottom up and took due consideration of the local practices. Our technical approach was flexible while ensuring the core principles for offsets. We were also relentless in our education efforts. All of these pointed to a system that was efficient with lowered transaction costs. When there are low transaction costs, emissions trading can bring enormous benefit to the rural poor. I recalled that Sabu from The Jungle Book had always dreamed of becoming a forestry officer. This alleviated the disappointment, but I was still determined to find a project that worked.

Holy Cows and Sacred Forests

Doing business in any new country requires great respect and acknowledgment of its culture and social systems. This is even more important in a country such as India, with its rich and complex set of social dynamics and cultural fabric.

Sometime back in 2006, CCX made several attempts to register forest carbon from India to our forest offsets portfolio. We had been very successful in recruiting Brazilian forest companies to CCX and were eager to extend the success to India. Murali traveled to Mathura to discuss this opportunity with the local district forest officer. I recalled Sabu's dream of becoming a forestry officer. Mathura, located about 90 miles from New Delhi, was a holy city famous for its Krishna temple. The city was believed to be the birthplace of the Hindu deity Krishna, and Hindu mythology was filled with tales of a young Krishna herding his cows in its lush forests. Mathura's bustling streets were filled with pilgrims and saffron-robed sadhus (Hindu holy men) and hawkers selling trinkets for Hindu rituals. The entire business in the city was somehow tied to the Krishna temple.

The discussion with the forestry department went smoothly. We discussed a pilot to initially demonstrate that the concept could be extended. A new plantation site was identified near the hillock of Govardhan as the pilot location. The site had year-old plantings and could easily be transformed to suit CCX forest carbon requirements. Murali suggested the continued development of the plantation. CCX would revisit the plantation in about six months’ time to measure the trees. When Murali returned to Chicago, we initiated the process of introducing Indian forestry tons to CCX. There was much work to be done.

Three months into the process, Murali received a frantic call from the forest officer. His plantation was being destroyed by an army of cows. Apparently, the local sadhus were insistent on releasing cattle onto the plantation. The Govardhan hills were part of the area that Krishna was believed to have roamed with his cows, and the sadhus would have nothing less than free-roaming cattle in these sacred forests. Of course, the cattle were devouring the young plantation. To add to the destruction, people were releasing monkeys into the forest in an attempt to appease the Hindu monkey god, Hanuman. When the forestry officer tried to disperse the crowds of sadhus, they become violent and started blocking the highway. This was something our experience designing carbon markets had not prepared us for. We had planned for many project risks, and had lined up detailed strategies and contingency plans, but had not anticipated being taken over by saffron-robed Hindu holy men. Confronted with that, we ended our first attempt to register forest tons from India.

The Tata Motors Auction

The Tata conglomerate, first set up with a steel company in 1907 by its visionary founder, Jamshedji Tata, had been nation builders in India for more than a century. The group's 90 subsidiary companies had interests in virtually every aspect of everyday life, and had long been associated with promoting education, arts, and other socially responsible endeavors. They had built hospitals, some of India's best educational institutes, and had even started civil aviation in India.

The Tata family were Parsees, a faith based on Zoroastrian tradition. The Parsees immigrated to Gujarat, India, in the tenth century from Iran. I had learned the story of the Tata family from Sanjib, who was a Parsee. We spent hours in my room discussing the bittersweet story of the Parsee religion and its tenets. He had told me, “There is no intermarriage and they don't accept conversion to their religion. Their population in India is doomed to disappear. Today, there are only 100,000 Parsees left in India.” The Tatas epitomized all that the Parsees valued. They were highly educated, successful business owners, and very philanthropic.

The Tatas had given Murali, a young student with aspirations to get an education in the United States, a scholarship that paid for his airfare and some tuition at the University of Kentucky. So naturally, when I asked him to name the top five companies that were interested in a nation-building project such as the Indian version of CCX, Murali immediately suggested the Tata group. I was thrilled to finally meet this illustrious family.

I asked Murali to make a pitch to the general manager of government affairs and collaboration at Tata Motors. The Tatas already had some experience in the carbon market through the CDM market. The manager well understood the impact the Tatas could have on the other Indian corporations and the importance of being the first mover, should a mandate for greenhouse gas reductions be introduced to India. In November 2006, Tata Motors signed up to be the first Indian automotive company to join the India Climate Exchange.

Our trading platform for CER futures was another service we could offer, especially to our Indian and international clients, who were the primary sellers in the marketplace. Our focus therefore was to get the Tatas involved with our CER futures marketplace.

Tata had some 165,000 CERs from a wind farm maintained by the company in western India that could be traded using our futures market. The general manager wanted the trade to be done within the next 10 to 15 days, so he could include the revenues in his fourth-quarter financial statements. Unfortunately, our CER futures contract was cash-settled and did not require the physical exchange of the underlying commodity. It was designed as a pure financial hedging tool.

Given this dilemma, we decided to offer a CER spot auction for Tata. Coupled with our advances in China and India, it made perfect sense to offer this service. The CER market was opaque, and transaction costs were high. Sellers of CERs in India often had to shop for the best prices without a central market. The success with the Tatas would showcase to the Indian corporations the power of markets and help with our strategic vision for the country.

I explained the importance of the CBOT SO2 auctions that Mike and I helped to originate and administer for many years. We wanted to be the first exchange to conduct an auction for CERs. I said to Rafael, who was Brazilian, with a smile, “If we pull this off in time, maybe we can beat your fellow countrymen to it!” The Brazilian Mercantile & Futures Exchange (BM&F), the local futures exchange, had just announced its own plans to conduct the world's first exchange-based CER auction in São Paolo. The expected auction date was September 26, 2007, but there was some uncertainty. Here was our opportunity to be the first exchange in the world to conduct a CER auction. This was another David-versus-Goliath scene, and we were playing David. It was eventually decided that the auction would be conducted on September 24 from the early morning hours until noon.

While the opportunity was tempting, the task at hand was immense. Within a span of the next 10 days, the legal contract for conducting an auction had to be written, an escrow account set up, marketing initiated, auction rules and specifications written, the press informed, and complicated bureaucracy of CDM mastered so the spot tons could be delivered. We had to work closely with the Tatas to carry out these tasks while grappling with the 11-hour time difference. We had a job to be done that spanned all our departments. We set two daily meetings—one in the morning and one to end the day—so we could update each other and take stock of the progress. At night, our job was to coordinate with Tata so they could get their necessary approvals and processes internally and have feedback for us early in the morning. It was kind of like a relay race, only one that was run 8,000 miles apart.

As we approached the auction date, there was a nervous energy from the team. While we had received interest from many companies, no one had confirmed their commitment to participate. We certainly didn't want a scenario in which there were no bids during the auction. A lot of hard work had gone into setting the stage for this auction and we didn't want to let Tata down.

The night before the auction, September 23, Mac McGregor and Kathy Lynn decided to stay overnight in the office. The expectation was that European clients could put in bids overnight and we wanted to make sure there was sufficient operational and marketing support in case they needed it. Morning came and there were still no bids. Anxiety climbed. Unrelentingly, Mac and Rob continued to make calls. Rafael wrote a draft press release to announce the results, despite the fact that we didn't even know if we would have results to share.

Amid all this frenzy, the fax machine started buzzing. We received our first bid for 30,000 tons. This was quickly followed by another. By the end of it, the auction was oversubscribed 13 times for the quantity available with 16 bids. More importantly, the power of competitive markets had been proven. Our clearing price of $22.11 per CER was slightly above the prevailing spot price.

Table 23.2 ICX Members as of March 2008

Tata was able to monetize its environmental service and include it in its financial report. CCX was now the first exchange to conduct a CER auction, beating BM&F by two days.

After the disbelief wore off, Murali inquired why Tatas had chosen CCX. The general manager responded, “I know all about making the best cars but selling carbon is not my forte. We were approached by many brokers who offered to buy these outright. However, the process of how we go about selling this is important to us. We wanted a regulated, transparent platform where no one could question our intentions. We wanted a credible organization that we knew we could trust.” I could not have been prouder of the CCX team. Table 23.2 lists the ICX members as of March 2008.

Moving On

With the level of interest shown by Indian companies and our successes in its offset market, we were convinced that we could help India develop its own voluntary cap-and-trade system. But first, we needed a strategic partner. We found one, and spent about nine months laying out an elaborate business plan and budget. Unfortunately, we entered into an agreement to sell Climate Exchange PLC before we could achieve our objectives in India. While the sale of the company was in the best interests of the shareholders, I deeply regretted our failure to set up the India Climate Exchange. India was an immense educational experience and we have gained a tremendous amount of goodwill among our participants. My mission to help India realize its environmental goals was not yet complete.

There remains significant interest in the Indian private sector with regard to cap-and-trade. India is currently experimenting with a national environmental market for renewable energy credits and a tradable energy efficiency marketplace. This is only the beginning of a bright future for the country. We remain very optimistic about India.

I thought that India would be more promising than China. But fortune favored us in China.

1India's priestly and scholarly social class.

2Bania is an occupational caste of bankers, money lenders, dealers in grains and spices, and in modern times, numerous commercial enterprises.

3A phut-phut is a modified Harley-Davidson with a carriage designed to serve as a rickshaw, prevalent in northern India.

4Purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusts the exchange rate for two countries so that an identical good in the two countries has the same price.

5World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Fund.

6Donald G. McClelland, Mark Hodges, Vijayan Kannan, and Will Knowland, “Urban and Industrial Pollution Programs, India Case Study,” Center for Development Information and Evaluation, Agency for International Development, January 23, 2001.

7Ibid.

8Our Planet, Our Health: Report of the WHO Commission on Health and Environment (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1992).

9Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Health Information of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, 1995, 1996.

10Bullion was introduced in 1920, jute in 1912, and wheat in 1913.

11The Indian Commodities Act of 1957 was modified in 2002.

12National Multi-Commodity Exchange of India Limited (NMCE) on November 26, 2002; Multi-Commodity Exchange of India Limited (MCX) November 10, 2003; National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange Limited (NCDEX) on December 15, 2003.

13D. G. Prasad, “Carbon Credit: Future Is in Commodity Exchanges,” Hindu Business Line, December 5, 2006.

14New Delhi–based TERI is a leading global think tank and India's premier organization involved in environmental and energy policy.

15Delhi GHG Forum 2006, January 31–February 1, 2006, Silver Oak, IHC, New Delhi. Program found at www.teriin.org/index.php?option=com_events&task=details&sid=126.

16“100 Million More Indians Now Living in Poverty,” Reuters, April 18, 2010.

17A memorandum of understanding (MOU) is a nonlegally binding, or soft commitment, between two companies on an agreed-upon course of action.

18“CCX and TERI Announce Partnership to Develop Greenhouse Gas Emission Offsets in India,” Press Release, Chicago Climate Exchange and the Energy and Resources Institute, August 21, 2006.

19India Climate Exchange™ (ICX™) Advisory Board, Chicago Climate Exchange, November 22, 2011, http://prod2.chicagoclimatex.com/content.jsf?id=1602.

20“The Andhyodaya Joins Chicago Climate Exchange as an Offset Aggregator, First Indian Offset Credits Approved for Trading in the Exchange,” Press Release, Chicago Climate Exchange, January 23, 2007.