Proposals are summations, not explorations. Ironically, consultants aren't more successful in getting their proposals accepted when they send out too many, rather than too few. This isn't a numbers game; it's a quality game.[39] (I once worked with a consulting firm in New York that actually used as a metric of success how many proposals were submitted a week. When I asked what the hit rate was, they told me they weren't instructed to track that!)

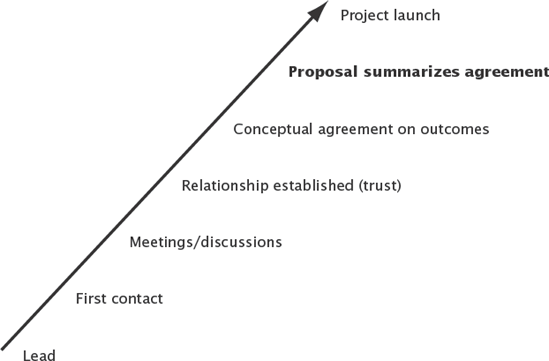

The key to an effective proposal is gaining the conceptual agreement beforehand (described in the prior chapter). Consequently, a proposal isn't a document or an event, or a one-time crucible in which the business is gained or lost. It's simply a normal (though highly important) part of the sales acquisition process. (See Figure 7.1.)

There is a methodical sequence you can use to write proposals. A good proposal needn't be much longer than two or three pages, no matter how large the contract or how elaborate the methodology, because the proposal should not be serving as a negotiating document, a sales brochure, a credibility piece, or any other purpose. It should simply be placing the conceptual agreement in context with other required elements of a good proposal (for example, accountabilities, terms, and so on).

Finally, proposals shouldn't attempt to be legal contracts, with boilerplate language, "parties of the third part," "agree to hold harmless," and other such legalese. There are several critical reasons to keep proposals conversational, not legalistic:

This is a relationship business. You should be willing to begin a project on a handshake with a true buyer with whom you've developed a trusting relationship.

Legalese will immediately be sent to two places you never want to go: the legal department and the purchasing department. Either place will delay, crush, attempt to abbreviate, and try to change the project for its own interests. If I speak disparagingly about these departments, it is deliberate.

The notion of protection through a legal contract is silly, since you're dealing with clients who will have the resources to contest anything written on paper in any case, and you don't have the resources to contest a contract for too long before you'll lose money even if you win.

In the best of cases, a legal contract will cause delay while it is being routed to the right people for approval, and delay is never good. Only bad things happen during delays. No one ever comes back and says, "Make it bigger."

Lawyers are paid to be conservative and avoid all risk. They'd prefer that the building not even be opened in the morning. Hence, the potential dangers of an interventionist consulting project creates shock waves that reverberate throughout the legal department. (I'm being hypothetical. In reality, it's much worse than this.)

Let's begin with the parameters of what proposals can legitimately and pragmatically do and not do:

Proposals Can and Should Do the Following

Stipulate the outcomes of the project.

Describe how progress will be measured.

Establish accountabilities.

Set the intended start and stop dates.

Provide methodologies to be employed.

Explain options available to the client.

Convey the value of the project.

Detail the terms and conditions of payment of fees and reimbursements.

Serve as an ongoing template for the project.

Establish boundaries to avoid scope creep.

Protect both consultant and client.

Offer reasonable guarantees and assurances.

Proposals Cannot and Should Not Do the Following

Sell the interventions being recommended.

Create the relationship.

Serve as a commodity against which other proposals are compared.

Provide the legitimacy or credentials of your firm and approaches.

Validate the proposed intervention.

Make a sale to a buyer you have not met.

Serve as a negotiating position.

Allow for unilateral changes during the project.

Protect one party at the expense of the other.

Position approaches so vaguely as to be unmeasurable and unenforceable.

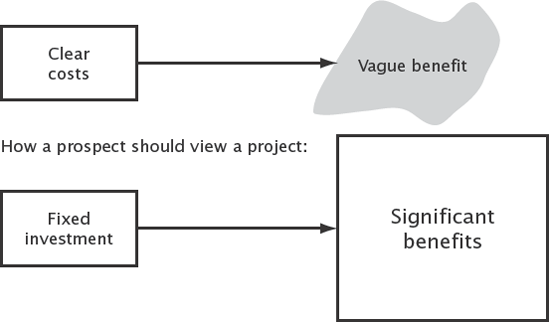

The climate or perception that a good proposal creates with the buyer is shown at the bottom of Figure 7.2, as opposed to the top perception, which is too often the default position unless we educate the buyer differently.

Here is the sequence that I have perfected over the years. It isn't sacrosanct, meaning that you may choose to add two more steps, delete one, or otherwise modify it to your best interests. However, if you follow my general sequence, and you've gained conceptual agreement beforehand, I can guarantee that you'll take less time writing proposals and gain a higher degree of acceptance the very first time. You can't beat those benefits.

Situation appraisal.

Objectives.

Measures of success.

Expression of value.

Methodologies and options.

Timing.

Joint accountabilities.

Terms and conditions.

Acceptance.

What: The situation appraisal consists of one or two paragraphs that reiterate the nature of the issues that brought you and the prospect together.

Why: This allows you to start the proposal on a basis of prior understanding and enables the prospect to figuratively (and sometimes literally) nod her head in agreement at your opening paragraphs. Psychologically, you're starting on a series of small yeses.

How: Simply define the current issue with as much brevity and impact as possible. Don't state the obvious, but focus on the real burning issues.

Example: Here's a poor situation appraisal:[40]

Boston Gimungus Bank is the eighth-largest bank holding company in the United States, headquartered in Boston, and continually seeking growth through mergers and acquisitions of institutions providing synergy to the bank's strategic goals.

Your buyer is aware of this. It sounds like something from the annual report. Here's a far better example for the purposes of your proposal:

Boston Gimungous Bank has recently merged with BankHugantic, which has created both expected and unexpected cultural problems among the Private Clients Group and within the human resources function. The new organization is seeking to create a new culture in these two units that represents the best of the strengths of each former organization, and to do so without disruption to client management and retention. In addition, superfluous positions must be eliminated while providing ethical and legal protection to employees in the form of transfer, reassignment, and outplacement.

The second example demonstrates why you were contacted, what issue must be resolved, and why it's of significant import.

Summary: The situation appraisal leads off the proposal by reminding the buyer of the nature and urgency of the issue to be addressed, and gaining a connection with your prior conversations and conceptual agreement.

This is the first of three elements in conceptual agreement.

What: The objectives naturally follow the situation appraisal in order to move from the general to the specific. The objectives are the business outcomes to be achieved as a result of your intervention with the client.

Why: The specific business outcomes are the basis for the value that the client will derive, and constitute the raison d'etre for the project. Unless business outcomes are achieved or enhanced, there is no real reason to invest in any change. Also, clear objectives prevent scope creep later, enabling you to explain to the client that certain additional (and inevitable) requests are outside of the objectives established.

How: List the objectives, preferably with bullet points, so they are clear and strongly worded. Objectives should be fairly limited, since you can accomplish only so much with any given intervention, or else they are simply pie-in-the-sky wishes and not practical business objectives.

Example: I discussed outputs versus inputs in Chapter 6, so the list of business-based outcomes might look like this:

The objectives for the project will be to:

Determine the leanest management team required to speed decision making and reduce overhead.

Determine the best candidates for those positions and recommend them on the basis of objective criteria to ensure the finest possible leadership.

Improve new business acquisition by creating and separating a new business development team.

Improve current response levels by investigating customer needs, anticipating future needs, and educating service staff accordingly.

This is the second of three elements in conceptual agreement.

What: These are the indicators of what progress is being made toward the objectives, and of when the objectives are actually accomplished.

Why: Without measures or metrics, there is no objective way to determine whether your intervention is working—or worse, if there is huge success, whether you've had anything to do with it! The metrics enable you and the buyer to jointly determine both progress and your role in achieving it.

How: Measures can be both quantitative and qualitative, the latter being acceptable as long as there is agreement on whose judgment or values are being used to assess results.[41] They should be assigned so that every objective has effective progress indicators to evaluate success.

Example: Measures are also best written in bullet-point form, with precise reference back to prior discussions with the buyer.

As discussed, the measures for this project will be:

Current client base is maintained for at least three months with less than 5 percent (industry average) attrition.

Client base begins to grow at a greater rate than historical rate beginning six months from now.

New management team and structure are in place within 30 days.

Any managers or employees without a position after restructuring are reassigned or outplaced within 30 days, with no grievances or lawsuits filed.

Staff survey on morale shows improvement from current levels in six months.

Customer surveys reveal increased happiness with response levels and ability of service team to handle concerns within six months.

This is the third of three elements of conceptual agreement.

What: This is the description of improvement, enhancement, and success that the organization will derive as a result of a successful project.

Why: It's vital for fee acceptance that the buyer be intimately and emotionally connected with the benefits to the organization (and to the buyer) so that the fees that appear later in the proposal are seen as appropriate and even a modest investment for the perceived value return. Otherwise, the fees will be seen as costs and will be attacked to try to reduce them. Note: Costs are always subject to attempts at reduction, but investments are almost always justified if the return is perceived to be significant and proportional.

How: You may wish to enumerate the value in a narrative or in bullet points. I prefer bullet points because they keep things unambiguously simple and direct.

Example: The value should be expressed in business-related, bold terms, per your prior discussions.

The value that the organization will derive from the successful completion of this project will include but not be limited to:

Overhead costs and administrative expenses will decline by approximately $600,000 annually through the reduction of direct salaries, benefits, and certain support activities.

A growth in the customer base of average private client assets will equal additional assets of about $1 million for each 1 percent gain.

Reduction in the attrition rate to the industry average will result in assets not lost of about $1 million for each 1 percent retained.

The ability to anticipate customer needs and suggest applicable additional products should result in additional revenues of $400,000 annually, growing at a rate of at least 5 percent.

Reduction in unwanted turnover of top performers will improve morale, create better succession planning, and improve client relationships since customers will not be losing their familiar faces.

This sequence is often misunderstood, so let me explain it again this way:

Objectives: Those business outcomes to be achieved due to a contribution from this project.

Measures of success: Those indicators that inform us of progress along the way and, ultimately, degree of success.

Value: The impact on the organization (including but not limited to people, finances, customers, repute, strategic goals) from meeting the objectives according to the metrics.

In the event you have very long-term objectives that may be met long after the project itself is complete, make sure your measures of success focus on shorter-term, interim steps. For example, if your objective is a market share increase that can't reasonably be expected until the next season or beyond, emphasize measuring that proves that progress is being made; for example, new shops agreeing to take merchandise, existing shops agreeing to take new products, higher public recognition of the product in focus groups, and so forth.

What: This is the section where you provide the buyer with an overview of the varying ways you may address the issues. Note: These are not deliverables, which many consultants confuse with outcome-based objectives. A deliverable is usually a report, training class, or manual, and has very little intrinsic value.

Why: In presenting the buyer with options, you are creating a choice of yeses so that the buyer moves from "Should I use Alan?" to "How should I use Alan?" This is an extremely important nuance, and one that you control. Proposals with options have a much higher rate of acceptance than those that are simply take-it-or-leave-it binary (accept or reject) formats.

How: Explain to the buyer that there are several ways to achieve the objectives, that all of them will work, but that some options provide more value than others. Therefore, the buyer should have the flexibility to decide on what kind of return is most attractive in relation to the various investments.[42]

Note that the options are separate and stand alone, and that any of the three will meet the objectives as stated. It would be unethical to propose options that do not meet the agreed-upon business outcomes. However, options 2 and 3 provide more and more value in the form of more valid data, more inclusion, more focus on business retention and acquisition, and so on. These are not phases or steps that run sequentially. Nor are they needs analyses, which unduly delay any project.

By offering the buyer a choice of yeses in the form of increasing value, you tend to migrate up the value chain toward more expensive fees. I call this the Mercedes-Benz syndrome: Buyers expect to get what they pay for. (If it's a Mercedes, one assumes that the engineering is top-notch and the reliability is superb.)

Always provide stand-alone options for your buyer to consider, and you will increase the rate of proposal acceptance exponentially. It is not necessary to detail how many focus groups, how many interviews, how many people trained, and so on, because with value-based billing, the numbers of days and numbers of people are irrelevant. The client might ask you to include another 10 people or you may decide you need four fewer focus groups, but it has no bearing on fees. The value of the results are all that counts.[43]

What: The timing section gives an estimate of when the project should probably begin and end.

Why: Both the buyer and you need to know when services will be performed, when results are likely, and when disengagement is probable.

How: Provide a range of time, since nothing is completely within your control, and always use calendar dates, not relative dates such as "30 days after commencement," because you and the client might have different perceptions of starting dates and other milestones. But the calendar offers concrete terms.

Example: Provide timing for each option.

For all options, we estimate a March 1 starting date. Option 1 should be completed in 30 to 45 days, or between April 1 and 15; option 2 should be completed within 45 to 60 days, or between April 15 and May 1; option 3 should be completed within 60 to 90 days, or between May 1 and June 1.

What: These are the responsibilities of the client and you to ensure that the project is successfully undertaken and completed.

Why: One of the most frequent causes of a consultant's being accused of not doing a good job is that the client didn't actually support the project as agreed or didn't supply resources in a timely manner. This is the part of the proposal that prevents that potential disaster.

How: State simply what is the client's responsibility, your responsibility, and joint responsibilities. These will depend on the nature of the project, and should be specific to each one. For example, an executive coaching project, an information technology (IT) project, and a recruiting project will have very different accountabilities.

Example: Given the ongoing scenario:

Boston Gimungous Bank will be responsible for making employees available for confidential interviews, informing them of the project, and providing a private area to conduct the interviews; for providing information about the business and past performance indexes to evaluate competencies; for adhering to the payment schedules established for this project; for client names and contact information for interviews; for reasonable access to senior management for ongoing progress reports, discussions, and problems; and for coordinating work flow and priorities to allow for the project to meet its time frames.

We are responsible for all interviews, focus groups, surveys, and other interventions called for in this proposal; we will sign all appropriate nondisclosure documents; we carry comprehensive errors and omissions insurance;[44] we will ensure minimal disruption in work procedures and adhere to all schedules; we will provide updates and progress reports at your request; we will immediately inform you of any peripheral issues that emerge that we think merit management's attention.

We will both inform each other immediately of any unforeseen changes, new developments, or other issues that affect and influence this project so that we can both adjust accordingly; we will accommodate each other's unexpected scheduling conflicts; we agree to err on the side of overcommunication to keep each other abreast of all aspects of the project.

What: The terms and conditions component specifies fees, expenses, and other financial arrangements.

Why: This must be established in writing in case the buyer changes, company circumstances change, and so forth. But most important, this is the first time the buyer actually sees the investment options after basically being in agreement with your entire proposal thus far. Stated simply: You want to prolong the head nodding in agreement right through the fees section.

How: Cite the fees clearly and in an unqualified manner. Cite expense reimbursement policy in the same way, also stressing what is not going to be billed. Provide in this area any discount you offer for advance payment (see the fees chapter, which follows this one). This section needs to be short, crisp, and professional.

Example: Using our current three options:

Fees: The fees for this project are as follows:[45]

Option 1: $58,000

Option 2: $72,000

Option 3: $86,000[46]

One-half of the fee is due upon acceptance of this proposal, and the balance is due 45 days following that payment. As a professional courtesy, we offer a 10 percent discount if the full fee is paid on commencement.[47]

Expenses: Expenses will be billed as actually accrued on a monthly basis and are due on receipt of our statement. Reasonable travel expenses include full coach airfare, train, taxi, hotel, meals, and tips. We do not bill for fax, courier, administrative work, telephone, duplication, or related office expenses.

Conditions: The quality of our work is guaranteed. Once accepted, this offer is noncancelable for any reason, and payments are to be made at the times specified. However, you may reschedule, postpone, or delay this project as your business needs may unexpectedly dictate without penalty and without time limit, subject only to mutually agreeable time frames in the future.[48]

We've established a quid pro quo here that means that the client can't cancel and must make payments as scheduled; there is no risk, however, because we will refund the fee if the quality of our work is not as promised (it is unethical to guarantee results being met due to uncontrollable variables such as turnover and competitive acts), and there is no penalty for rescheduling or postponing the project.

What: The acceptance is the buyer's sign-off indicating approval to begin work.

Why: No matter how trusted a handshake or an oral approval, conditions in client companies change frequently, and you have to have a signed agreement to enforce your rights.

How: Include this as the last item in the proposal, with room to sign off, and return one of two copies. Execute your signature ahead of time to speed up the process (in other words, don't wait for the buyer to sign, then sign yours, then return the buyer's copy). This circumvents the need for a separate contract, involvement of legal, involvement of purchasing, and all the other landmines that lurk beneath the ground. Also, by specifying that "a check is as good as a signature" in the verbiage, you're saying that paying you the deposit deems that all terms have been agreed upon.[49]

Example: These are fairly standard, and can be inserted into any proposal.

The signatures below indicate acceptance of the details, terms, and conditions in this proposal, and provide approval to begin work as specified. Alternatively, your deposit indicates full acceptance, and also will signify approval to begin.

For Summit Consulting Group, Inc.:

___________________

Alan Weiss, Ph.D.

President

Date:___________________

For Bank of America:

Name___________________

Title___________________

Date:___________________

Plan your follow-up in advance with the buyer. There are three ways to do this:[50]

In the discussions leading up to the actual creation of the proposal, mention that your habit is to give the buyer a day or two to review the details and options, and then to call to respond to any questions or to actually begin the project. You merely want to set the stage for your proposal management. (Don't provide the initial proposal in person if you can avoid it, since you want to give the buyer time to read it and think about it. This sounds counterintuitive, but it's an important tactic, preventing the buyer from saying, "I need more time," which would be quite legitimate.)

When you are actually ready to prepare the proposal, mention to the buyer the exact time he will be receiving it, and check for a good follow-up date. "I'll be sending this by courier so that it arrives on your desk Thursday morning. I'd like to call you between ten o'clock and noon on Monday to discuss your reaction. Does that fit your schedule?" If the buyer says no, that there's a field trip scheduled next week, then ask what a good time would be. Two key criteria:

You want a phone call (or personal visit), not e-mail or voice mail.

You want to initiate it, not the buyer, to ensure positive contact.

Mention your intent in your cover letter, which should be a brief note saying, "Here's the proposal you and I discussed." Let the buyer know that you'll be following up at a specified time and date. Leave nothing to chance. Invite the buyer to let you know if that arrangement is not agreeable, but stipulate that, unless you hear otherwise, you'll be contacting the buyer at that time.[51] This technique also enables you to say, "I'm calling as agreed."

Do both 1 and 2. If you constantly reinforce the fact that your normal policy is to submit a proposal rapidly after the conceptual agreement, then follow up promptly for reaction, and then are prepared to launch the actual project quickly, you will create the proper expectations—and, one hopes, behaviors—on the part of the buyer.

Sometimes the buyer will say, "We need to discuss this in person, and I'd like to get some other people in on it."

This is good news and bad news. The good news is that the buyer is willing to spend more personal time on the proposal, and wants to give you a chance to close the deal. The bad news is that the proposal itself wasn't sufficient, and that conceptual agreement might not have been as solid as you thought.

Some rules for a personal appearance follow-up:

Always accept. Don't try to close on the business by phone.

Arrange it as quickly as possible. Remember, the longer the process takes, the more that can go haywire.

Ensure that the buyer will be there personally. If she will not be, then arrange to see the buyer privately before and after the meeting with subordinates or colleagues.

Find out who else will be there. Ask the buyer whether the proposal can be made available to them so that everyone is at the same level of understanding.

Ask quite candidly if there are any objections, drawbacks, unexpected developments, or anything else that you should know about and prepare for to make the best use of everyone's time. Don't wait for an ambush, and then go in unarmed, and refuse to fight. Determine who will be shooting, from where, and with what, and arm yourself accordingly.

Test the status. Ask, "If we can reach agreement at that meeting, are you prepared to proceed?" Try to get the buyer to commit to a proposed course of action (for example, amend a part of the methodology and we can go on, or shorten the time frame for data gathering and we can probably agree on a start date). If you're particularly assertive, ask this great question: "What will you and I (or you, your colleagues, and I) have to accomplish at that meeting so that we may begin the project?"

Be prepared for good news. You might just be clearing up some minor details or ambiguity, so be prepared to close the deal and shake hands. You'll want to be able to start immediately to pour cement on the deal.

If things are not resolved but still alive, make sure you do not leave without a definitive next step, including date and time and accountability. Example: "Okay, I'll bring an example of the survey I would intend to use to a meeting here on Friday at ten o'clock, and you will make whatever suggestions necessary to ensure cultural acceptance. Once we have that, you'll sign the proposal and I'll start the next week."

As a rule, the more specific the buyer is in response to point 6, the better your chances. The more vague the buyer sounds, the more trouble awaiting you. In point 8, you must return to the buyer, no matter who else might or might not be present.

Let's take one item off the table right now: fees. If the buyer says that your fees are too high—for all of your options—do not offer to lower fees. That tactic will either lose the business immediately ("Hmmm, how low can he go?") or will gain you business that you hate ("I'm actually losing money on this deal").[52]

Instead, offer to reduce value. That's right. All buyers want to reduce fees, but they seldom want to reduce value. Fees are never a question of resources, but rather of priority. The money is available somewhere, the only question being are you and your project important enough to the recipient?

There are other objections, unrelated to fees, that you might hear, either from the buyer in advance or from the buyer or colleagues at the actual meeting. They typically include:[53]

The timing is too aggressive or too tame.

Subordinates are threatened by the outside intervention.

Sensitive political or cultural issues are involved (for example, compensation).

A union is presenting problems.

Other projects, planned or ongoing, are threatened.

No matter what the objection, you should use the same tactic: Make the resistance a part of the solution. Don't attempt to smash through it, overcome it heroically, or throw yourself onto your sword ("You'll have to trust me on this, I've seen it before, and I'm confident we can overcome it").

Tell the buyer and others that the objection makes sense, and ask what they would recommend to overcome it. Tell them that you have some ideas and experience from other clients, but that they know their culture best and you'd be happy to work in their resolutions. At the same time, assure them that there are always objections, that the timing is never perfect (time is; life and money are matters of priority, not resources, since there is always time for important issues), and there will probably be some more stumbling blocks before this is over. "Nevertheless, successful projects are launched every day in far worse scenarios than this one and we're all intelligent people here, so let's work out the best resolution we can while we're together."

A personal appearance is still a fine opportunity. But take it very seriously and prepare assiduously: It's probably a make-or-break point.

A chronic complaint I hear from colleagues is, "We had such a good relationship, but the buyer won't return my calls!" Here are some safeguards:

Make your phone call as planned (agreed-upon day).

Make a second phone call, with a courteous message (next day).

Make a third and final phone call indicating your confusion and saying that you'll send something in writing (three days later).

Simultaneously send an e-mail and letter marked personal and confidential, politely asking for a response so that you can plan your time accordingly and offering to see the buyer personally, if desired (one week later).

Send a certified letter to the buyer indicating professionally that the proposal terms will be honored for only another 30 days, at which time all terms would have to be reviewed and renegotiated. Indicate that this will be your final letter (two weeks later).

I usually don't go beyond this, because I don't want to throw good money after bad, and I never take it personally. After all, just because your buyer has a personality disorder or is neurotic (one of which is probably the case with these disappearances) doesn't mean that you're a bad person. Further, psychologically, it's depressing to deal with this passive-aggressive rejection, so it's best to remove ourselves from it, which we're quite capable of doing.

If you want to escalate beyond my steps, however, here is the nuclear arsenal:

Ask the secretary if the buyer is sick or if something unexpected has happened; then find out what the buyer's schedule is. If the buyer is visiting the Philadelphia field office on Friday, for example, you can place a call there and almost assuredly ambush the buyer through an unsuspecting local switchboard operator.

Send an invoice to the buyer for your expenses to date (which you should actually absorb as marketing expenses) given the fact that the meetings and interaction were apparently to gain information from you but not to consider a project seriously.

Send an invoice for your fee in terms of the value you've provided, per step 7.

Send a letter with a copy of the proposal to the buyer's boss. Explain the steps you've taken to try to obtain a response, and that you're worried that your proprietary information, models, material, and so on might be used without your consent or appropriate payment. Ask if there is some way to resolve the impasse.

Send a certified letter to the buyer explaining that the buyer's failure to conform to your agreement for response and your consequent inability to determine the status of the project (and the material you've provided) mean that all agreements are null and void. Therefore, you do not feel constrained to conform to any real or implied nondisclosure agreement about what you've learned, nor will you return any of the proprietary materials the company has provided to you.

I do not advocate steps 6 through 10, but you may occasionally be unable to exorcise the demon of the disappearing buyer without resorting to stronger actions. I have met a couple of these people. If you think you're unfortunate for having had to deal with them, think of the great misfortune of their companies, which pay them significant amounts of money in support of unprofessional, aberrant behavior.

Even with this methodical approach of relationship building, conceptual agreement, proposal as summation, choice of yeses, and planned follow-up, you sometimes don't get the business. As someone once said, that's not a failure, only the start of a new opportunity.

First, find out the only important piece of information for the moment: Why? You can't do anything effectively until you learn the reason for your non-acceptance. The causes usually range among these:

A legitimate, competing proposal was accepted.

Your proposal was flawed in some way.

Despite value, you were deemed too expensive.

The project was canceled or postponed.

The prospect has decided to proceed using internal resources.

You weren't dealing with the true buyer.

There was an internal upheaval or reorganization.

Someone talked the buyer out of using you (you were a threat).

Poor profitability has put a freeze on all expenditures.

The situation unexpectedly improved or the problem disappeared.

Unexpected profits have diminished the problem's priority.

A scandal has occurred in the company (harassment, embezzlement, and so on).

The organization is being sold, merged, or divested.

New technology is eliminating the problem or opportunity.

There was a misunderstanding on your part.

There was a misunderstanding on their part.

Some combination of these.

Believe it or not, I've heard every one of these reasons and excuses after submitting proposals over 27 years as a consultant. The main reason to find out the cause of your rejection is that you want to be able to correct anything that was in your power to do so. Reasons 2, 3, 6, and 15 are the ones to learn from. You can correct your mistakes or omissions in future proposals (it's too late for this one). The others are simply part of the fates and futures that await all consultants, and there's no use getting upset about them.

Rejection needn't be the final bell. All that it signifies is that at that particular point, for that particular buyer, under those particular conditions, there wasn't sufficient perceived value. You've lost the battle, but the war is far from over. The good news is that you've met the buyer, you've established enough of a relationship to have been able to submit a proposal, and you know where the buyer lives. This is all the ammunition you'll need to begin mounting your counteroffensive.

For goodness sake, do not take rejection personally. It is not a commentary on your worth.

Here are the six steps to take to turn short-term rejection into long-term business:

First, never walk away angry. The failure to consummate a business deal isn't the buyer's fault or your fault. It's not about fault, it's about cause. Take your setback gracefully, thank the buyer for all of the support and interest she has demonstrated along the way, and, if another resource was chosen, say something nice about them and assure the buyer that you believe they'll do a fine job. Now, this is very important: Ask permission to stay in touch. This vague and simple request is rarely denied, but its acceptance by the buyer creates a legitimacy to the next steps. It's the difference between structured follow-up and incessant hounding.

Second, ask for the cause of your not being chosen. Tell the buyer that we all learn best with honest feedback, and in the spirit of improving your approaches and helping other clients better in the future, ask what you could have done better, included, omitted, or changed. Don't settle for generic pap. ("It was close—it could have just as easily been you who was selected." Yeah, but it wasn't.) Ask for specific areas to work on and, no matter what you think of the advice, demonstrably take notes. (If you're on the phone, say something like, "Just a second, I want to make a note of that.") Use the 17-point list of causes if you want to stimulate the conversation. Remember that there may be multiple causes.

Third, make an open offer to be of informal assistance if the buyer needs anything during the project (for example, another opinion, a sounding board, and so on). At that juncture, provide your card and brochure or media kit again, for future reference (these are often discarded after a consultant hasn't made the cut).

Fourth, mail something—virtually anything of some value—to the buyer a month later, and bimonthly thereafter. Let the buyer know that there are no hard feelings, and that you have his interests in mind on a regular basis. Don't attempt to resurface the project you lost out on; simply send articles and materials that are relevant for the buyer's position, company, and industry.

Fifth, call the buyer three to four months after your rejection, and ask any one of, or all of, the following questions: Has the material you've been sending been appropriate? Should you alter the content in any fashion? How has the project progressed? (If it's gone very well, indicate that you're delighted; if it's gone poorly, provide genuine empathy.) Tell the buyer that you'll be in the neighborhood on three different dates, and ask if you might have lunch or briefly meet on any of the three dates that might be convenient.

Sixth, if you can meet with the buyer while you're in the neighborhood, do so. During that meeting, develop a conversation about the current concerns and needs of the organization. Bring the buyer up-to-date on anything you've been doing that's relevant to the buyer's needs. If you're unable to arrange such a meeting, then go back to the fifth step over the phone.

If you're disciplined and unselfishly helpful, eventually the buyer will either agree to see you again or request that you submit a proposal on some issue that has arisen. I've been called continually through the years by people who originally did not click with me, or who did a small amount of business in an unrelated area, merely because I've kept in touch. Consistency is everything. Don't contact people only when you want something, or when it's convenient for you. Establish regular helping patterns. You've already done the hard part in establishing the relationship to begin with.

The legendary coach Vince Lombardi said once that his teams had never lost a football game, although occasionally they had run out of time before they could win it. You have all the time in the world if you're consistent, professional, low-key, and oriented toward a helping relationship.

Final thought: If you can send out just two proposals a month that average, among their options, $50,000 in fees, and you hit 75 percent of them, you have a practice that is generating $450,000 annually. That's just two a month, using this system! Do you think you can live on that, at least at the outset of your career in this profession?

Q. My attorney tells me that I need a formal contract in addition to the proposal. Isn't that safer?

A. No, any contract can be broken, and a trusting relationship with the buyer trumps legalese. Your lawyer will never read this book and charges by the hour, which is why he's suggesting you ask him to write your contracts.

Q. Can't an objective also be a value as you've explained it?

A. Yes, absolutely. If the objective is to increase profits by at least 2 percent, that could also be the value or impact. However, the additional value could be that there is more money for investment in R&D, more incentive for people in the profit-sharing plan to remain, and so on. So it needn't be a one-to-one ratio.

Q. Is it appropriate to be paid for travel days?

A. No. That's is just a cost of doing business, and in value-based pricing, your margins are huge and do not depend on where you spend your day. You are, of course, entitled to reasonable travel reimbursement, but never nickel and dime people by charging for copying or couriers and so forth.

Q. Can I use this proposal format when an organization insists on a reply to an RFP (Request for Proposal) in a stipulated template?

A. Yes. My advice is to complete the RFP and also attach your proposal to it. Remember that you can exceed the requirements of an RFP in your proposal, which can give you an inside track. However, RFPs are usually evaluated by low-level committees.

Q. Would I complete this type of proposal for every assignment?

A. No. For a simple training program or speech, a streamlined letter of agreement would do. For a retainer, which is solely access to your smarts, there are no specific objectives and you're more concerned about scope and timing. (See the next chapter on fees for more about this.)

[39] Although we're dealing with proposals in a full chapter here, if you want an in-depth approach, including templates in hard copy and on CD, see my book How to Write a Proposal That's Accepted Every Time (Peterborough, NH: Kennedy Publications, Second Edition, 1999, 2003) or find it on my web site: summitconsulting.com.

[40] I'm using a fictitious merger and organizations, but the specifics of the project are taken from an actual pair of assignments.

[41] For example, if several people all agree that the office aesthetics should be improved, it's far better to also agree that one of them will determine that, rather than try to gain agreement among several people on what is, basically, a subjective matter.

[42] And I want to emphasize that you still haven't discussed fees in any manner yet. Patience.

[43] I've long held that I'd be completely happy working 10 minutes a year for a single client for $5 million. My wife tells me that if I can work 10 minutes, I can work 20 minutes.

[45] These fees are entirely fictitious. Ignore the amounts and focus on the process.

[46] For non-U.S. business, you would specify in this section that all funds quoted are in U.S. dollars, and are to be paid in U.S. dollars drawn on accounts in U.S. banks. In that way, you will not be subject to exchange fluctuations or to severe bank fees applicable to exchanging foreign checks. Wired funds are usually fastest and best.

[47] Many organizations have a purchasing policy that states that all discounts must be accepted, meaning that you will always get the full fee less 10 percent in advance. That is 10 percent well invested on your part, since the money is in your pocket and the project cannot now be canceled (or at least the money can't be returned).

[48] This is my quid pro quo for a noncancelable project agreement.

[49] I actually had a client make two payments of $125,000 each over 45 days and completed a highly successful six-month project without ever receiving my signed proposal back. The reason was that it was far easier for the executive vice president I was dealing with to approve six-figure checks than it was to get an agreement through his legal department! So, "a check is as good as a signature!"

[50] Note: Since there are only so many ways to express simple concepts, much of what follows also appears in similar context in my book How to Write a Proposal That's Accepted Every Time, previously cited, and used with permission of the publisher.

[51] This is as good a time as any to mention that it's always a good idea to get the buyer's private line, private e-mail, and private fax number. Early in the relationship, you might provide your home phone number or private line on a card for the buyer, and ask if there is an expeditious way to reach him. This usually avoids gatekeepers entirely.

[52] For a detailed discussion of fees, see the next chapter.

[53] Don't forget, all of the foregoing assumes that you've been dealing with the real economic buyer. If subsequent events indicate that the resistance is caused by the fact that your presumed buyer doesn't really have that authority, then you must begin the courtship again by finding out who the real buyer is. You cannot sell anything to gatekeepers or recommenders.