2

A General Contractor: A Maven, A Connector

This chapter assesses the role of the general contractor in construction projects; it shows how their influence on a project’s final output is likely to vary based on contrasting intervention scenarios. This is particularly apt as general contractors are often disposed to play a series of roles in construction projects, rather than just one role1.

For this reason, instead of dictating the role of the general contractor, we attempt to describe it exactly as it is, factually and objectively. Ceteris paribus, we demonstrate how a general contractor can make a fundamental contribution to the success of large construction projects in general and, more specifically, to smart developments.

This chapter is structured as follows. First, a description of the construction industry value chain is given, followed by a list of change agents that have enabled improved value creation in construction in recent years. A comparison between old and new construction value chains and processes is also presented. Additionally, in relation to complex construction processes (smart constructions), a concise overview of innovation in construction is provided. The role (or roles) of the general contractor is then introduced and explained. Analogies between general contractors and other construction actors are also suggested when considering the administration of smart developments. The chapter concludes by demonstrating how general contractors and music conductors are, rather surprisingly, very much alike.

2.1. New value chains in construction

A value chain is essentially a model of the corporate value-forming process and was introduced by Michael Porter back in 1985 (Porter 1985). Used for decades to understand and analyze industries, it has been revered for its ability to portray the chained linkage of activities that exists within traditional industries. By definition, value chain analysis is a process whereby companies pinpoint the primary and secondary activities that add value to their final products and services. They subsequently scrutinize these activities to reduce costs or improve differentiation (Peppard and Rylander 2006). Thus, a value chain represents the activities that companies engage in when transforming inputs into outputs.

As products and services have become ever more dematerialized and value, more than ever before, is being created within networks and alliances (rather than by solitary stakeholders), the focus has progressively shifted towards value networks, denoting the co-creation of value by a group of actors within the network. Referring to Santoni and Taglioni (2015), a value network is a business analysis perspective that describes social and technical resources within and between businesses; it exhibits interdependence and accounts for the overall worth of products and services.

Far-removed from the value network approach, a superior concept has newly emerged – the shared value concept – positing that value creation should not solely benefit companies and/or customers but the society in its entirety. As expounded by Porter and Kramer (2011), by (naïvely!) concentrating on improving short-term financial gains, companies have a tendency to overlook the most pressing unmet needs in the market, as well as the wider influences affecting their long-term success. As a result, they remain stuck with a nonoperational, limited approach to value creation. Furthermore, they repeatedly disregard the depletion of natural resources, the viability of suppliers and the economic agony of the communities in which they operate; all key factors in the long-term success of their business. Similar conclusions can be found in Stabell and Fjeldstad (1998). Indeed, the authors assert that a threefold value configuration analysis (value chain, value shop and value network) is required in order to be able to examine and comprehend the logic behind firm-level value creation, not only in the realm of the construction industry, but across a range of other industries and sectors (see Table 2.1 for an overview of alternative value configurations).

As one of the world’s largest consumers of raw materials (contributing to roughly 40% of global GHG emissions)2, the construction industry is predicted to grow steadily between 2018 and 2023 at an annual rate of 4% – in terms of market value – with major growth prospects in residential, commercial and infrastructure projects (Gawer and Cusumano 2014). This anticipated growth, along with the decarbonization imperative, have created the impetus for sustainable construction. Today, construction companies are becoming more accountable for their contribution to global emissions and are therefore facing societal pressure to lessen negative externalities and find practical ways to decrease their carbon footprint. Similarly, Lehdonvirta et al. (2009) assert that the construction sector has actually transformed into a service industry and construction companies are now seen simply as service providers. This implies that the era of technical specification and cost minimization is rapidly coming to an end. We nevertheless remain hopeful by acknowledging that there are ample technology-driven prospects for the improvement of customer value creation in construction.

Table 2.1. Alternative value configurations

(source: adapted from Stabell and Fjeldstad (1998))

| Chain | Shop | Network | |

| Value creation logic | Transformation of inputs into outputs | Resolving customer issues | Linking customers |

| Primary technology | Long-linked | Intensive | Mediating |

| Primary activity categories | ▪ Inbound logistics ▪ Operations ▪ Outbound logistics ▪ Marketing ▪ Service | ▪ Problem-finding and acquisition ▪ Problem-solving ▪ Choice ▪ Execution ▪ Control, evaluation | ▪ Network promotion and contract management ▪ Service provisioning ▪ Infrastructure operation |

| Main interactivity relationship logic | Sequential | Cyclical, spiraling | Simultaneous, parallel |

Primary activity interdependence | ▪ Pooled ▪ Sequential | ▪ Pooled ▪ Sequential ▪ Reciprocal | ▪ Pooled ▪ Reciprocal |

Key cost drivers | ▪ Scale ▪ Capacity utilization | ▪ Scale ▪ Capacity utilization | |

| Key value drivers | Reputation | ▪ Scale ▪ Capacity utilization | |

| Business value system structure | Interlinked chains | Referred shops | Layered and interconnected networks |

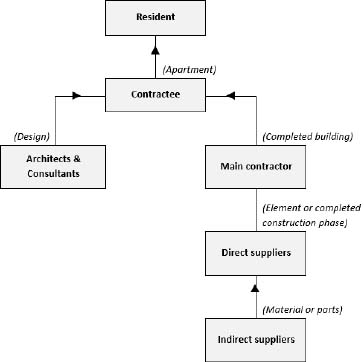

Figures 2.1 and 2.2 shown below respectively map the actual supply and value chains in construction.

Figure 2.1. The actual construction supply chain

(source: adapted from Vrijhoef and Koskela (2000))

Figure 2.2. The actual construction value chain

(source: adapted from Vrijhoef and Koskela (2000))

In the following, we briefly describe some of the change agents that have latterly given value creation in the construction industry a significant boost (see Table 2.2) (see section 1.8 for further insights into innovation in construction).

Table 2.2. Change agents in the construction industry

(source: created by the author from various sources

Additive Manufacturing Technologies (AMTs) —or— 3D Printing Methods | ▪ Campbell et al. (2012) summarized the benefits that could ensue from the adoption of AMTs by companies, namely: customization, improved functionality, reduction of total amount of parts and esthetics; ▪ AMTs have been predicted to revolutionize the construction industry (3DRS 2015); ▪ Lim et al. (2012) estimated the potential advantages of AMTs for construction and came up with the following: increased freedom of design, reduction in mold costs and integrated functionality of individual components; ▪ AMTs enable cost efficient manufacturing of large, geometrically complex, unique components, using materials that are applicable to construction; ▪ AMTs are highly relevant for the construction industry as it is directly linked to logistics, customization, virtual models and manufacturing. |

Virtual Reality Technologies (VRTs) —and— Augmented Reality Technologies (ARTs) | ▪ Several projects have employed VRTs/ARTs in visualizing BIM3 models (see Figure 2.3); ▪ VRTs/ARTs are changing manufacturing and enabling mass customization at an unprecedented level; ▪ Used to visualize 3D models in future construction sites, they help guide real-world construction activities (Behzadan and Kamat 2005); ▪ Consumer products enabling ARTs/VRTs have been announced by prominent ICT companies such as Samsung, Sony and Google. |

Multi-Sided Platforms (MSPs) | ▪ MSPs connect two or more sides of the market via online services, benefiting from network effects; ▪ They act as a foundation upon which external innovators can develop their own complementary products, technologies or services (Gawer and Cusumano 2014); ▪ Well-known examples of MSPs that disrupt traditional business models are: Uber (taxi services), Airbnb (accommodation services) and Amazon (retail services); ▪ MSPs thrive on data-driven customer understanding, enabled by faster innovation capabilities and greater profits than the general industry average (Weill and Woerner 2015). |

Without doubt, new knowledge and high-tech have been (and still are) creating competence-based growth and breakthroughs in some of the nascent fields of society today: artificial intelligence, robotics, navigation and data analytics. We believe the blanket adoption of these applications would eventually have the ability to transform the entire value chain of construction (see Figures 2.3 and 2.4).

Figure 2.3. The future of construction process

(source: adapted from Virtanen et al. (2014)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

When looking at the construction value chain (actual vs. future), it is easy to see that the variances occur at the beginning and during the later stages of the chain.

Economically, this suggests an incremental increase in value in very small steps to a hasty upsurge in value in one jump. If we consider Figure 2.4 (relative to Figure 2.2), the central operator3 has noticeably more control over the manufacturing process in terms of both scheduling and price determination. Moreover, the logistics and materials held in storage are reduced, limiting the amount of resources tied to the process. For clients (residents) and designers, the ability to customize is amplified; thus, fewer conciliations are needed to fit the design to the offerings of manufacturers. In the final parts of the chain, the central operator turns into a central stakeholder. For small-sized operations, the roles of designer, manufacturer and contractor may be merged into one. This is made possible by the clients who provide digital data of the site and make use of IoT; this enables clients to make some design decisions and to make use of AMTs for the production of more complex components. Overall, the number of stakeholders involved in the construction process is reduced, resulting in fewer communication and procurement steps.

Figure 2.4. The future construction value chain

(source: adapted from Virtanen et al. (2014))

Currently, a number of concerns surround the analysis of future construction value chains. In particular, these center on the fact that the predictions made – which are often deemed unsatisfactory – account for technical developments only. In addition, it seems very optimistic to assume that a single value chain could serve all situations encountered in the construction industry. For example, retrofitting a single apartment and building a new residential area are inherently distinct projects, of completely different scales; the producer–customer relationships involved also differ significantly. Thus, it is inconceivable that a common value chain exists, able to precisely fit to all types of construction projects (Virtanen et al. 2014).

2.2. The construction project lifecycle

Every stakeholder involved in the process of scheduling, planning, sponsoring, building and operating physical facilities related to construction projects gains different viewpoints over time on project management for construction (Figure 2.5). Indeed, contributing expert knowledge could be very advantageous, particularly when it comes to large and complicated projects (smart developments). In the same way, it is of foremost importance for all stakeholders to understand how the constituent parts of a construction process are connected together.

As conveyed by Hansen and Birkinshaw (2007), poor coordination and communication between stakeholders could eventually result in waste, excessive costs and unwelcome delays. It is typically the responsibility of the project owner (and to a lesser extent the project manager) to assure that such issues do not occur. Egbu (2008) found that the implementation of the project owner’s viewpoint would help stakeholders to focus on the completion of the project by paying close attention to the details of the process of project management for construction projects. Indeed, this would be a move away from the old concept of making decisions based on the bygone roles of stakeholders involved in the project (e.g. project owners and managers, architects, general contractors and others).

Following this logic, stakeholders would contribute their expertise through opinions on improving the productivity and quality of their works. For construction actors to be able to make substantial improvements, they must first know the construction industry, its working environment and the institutional constraints affecting its activities, as well as the nature of project management (Carassus 2004). It is therefore prudent for project owners to have a solid understanding of the whole construction process in order to maintain control of the quality, suitability and budget of the finalized project.

The typical CPLC – represented in Figure 2.6 – consists of five major phases, explained in Table 2.3. In addition, a complete view of a construction management process is shown in Figure 2.7.

In practice – depending on the nature, size and urgency of the project – these development phases may not always be sequential as some may require iteration and others may be carried out across overlapping timeframes. Further to this, it is worth asserting that project owners are likely to establish in-house capacities to handle the works in every phase of the construction process. Yet, if impossible to do so, they tend to outsource part – or all – of the jobs by seeking external expertise. This expertise may come from a general contractor or a construction manager, for instance, who could conduct and monitor the works carried out at every stage of the project.

Figure 2.5. The building blocks of a construction project process

(source: adapted from Direction des Immobilisations and Cloutier (2005). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

Figure 2.6. Major CPLC phases (a)

(source: compiled by the author4). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

Table 2.3. Major CPLC phases (b)

(source: compiled by the author5)

| I | Initiation | ▪ Identify objectives or needs ▪ Carry out feasibility study ▪ Initiate project to implement approved solution/s ▪ Appoint ‘project manager’ ▪ Identify major deliverables and participating work groups |

| II | Planning | ▪ Identify all of the works to be done: tasks, resources and strategy ▪ Build a project plan outlining activities, tasks, dependencies and timeframes ▪ Scope Management: Coordinate project budget (cost estimates for labor, equipment and materials) by project manager ▪ Monitor cost expenditures during project implementation ▪ Provide quality targets, assurance and control measures ▪ Define acceptance plan, listing the criteria requested by customers |

| III | Execution | ▪ Put project plan into motion ▪ Perform assigned tasks (by construction actors) ▪ Communicate work progress through regular team meetings ▪ Compare progress reports with project plan to measure the performance of project activities ▪ If needed, plan corrective measures (to bring the project back to the original plan) ▪ Keep key stakeholders (including project owners) informed about the project’s status ▪ Indicate possible end point in terms of cost, schedule and quality of deliverables in status report ▪ Review deliverables for quality, against acceptance criteria |

| IV | Performance & Monitoring | ▪ Measure progress and performance of project activities (in tandem with execution phase) ▪ Track project activities with project management scheduling |

| V | Closure | ▪ Provide final deliverables to ‘client’ ▪ Project documentation handover to the business ▪ Terminate supplier contracts ▪ Release project resources ▪ Communicate closure of the project to stakeholders ▪ Conduct lessons-learned studies to examine what went well and what went wrong |

Figure 2.7. The construction project management process

(source: created by the author). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

2.3. Innovation in construction

Innovation could be a key source of competitive advantage for construction companies (Slaughter 2000). Yet the construction industry is an example of a sector in which conventional measures do not convey the true extent of the innovative activity that is actually occurring – and is often seen as one of the less inventive sectors (Barrett et al. 2007). We believe this observation is somewhat unwarranted because much of the inventiveness remains out of sight as it is co-developed at the project level. As a project-based industry that is largely disjointed, types of innovation in construction differ from those of others. Though a significant amount of research has been conducted to date, more is needed to investigate different types of original activities carried out throughout the CPLC.

As per Gann and Salter (2000), project-based companies need to manage their project processes and business models effectively given their resources are embedded within both project- and company-levels. “It is the integration of these two sets of resources that enables the firm to be competitive” they added. On another note, Brusoni et al. (1998) indicated that business models are ongoing and repetitive, whereas project processes are more likely to be temporary and unique. This is the reason why companies must continually incorporate project experience into their business models to ensure coherence in their work.

Currently, there is a growing tendency to take a broader view of innovation in construction, one that reflects the many ways in which innovation occurs in practice. Damanpour’s (1992) definition of innovation is suitably inclusive: “it is the adoption of an idea or behavior, whether a system, policy, program, device, process, product or service, that is new to the adopting organization”. Phillips (1997), on the other hand, distinguished between technological innovation and organizational innovation. For the author, the former incorporates substantial technological improvements in products and processes, whereas the latter involves major changes in organizational structures. Furthermore, Slaughter (1998) suggested five innovation models ranging from incremental innovation – slight changes based on current knowledge and skills – to drastic innovation, for example a technological breakthrough that alters the entire nature of an industry. Subsequently, Blayse and Manley (2004) emphasized that construction is partly manufacturing and partly service industry and, crucially, that the characteristics of innovation in the service industry are different from those in the manufacturing industry.

As a weighty economic variable, the measurement of innovation has attracted a great deal of attention among academic circles in recent years. However, due to the intricacies of construction processes in general, evaluating innovation remains a difficult task to accomplish. In general, construction is a very diverse sector and there is no precise way in which innovation occurs. As per Lansley (1996), the occurrence of innovation within the construction industry is often characterized by the continuous adoption of new practices because of advances in technological processes and business models. For Barrett et al. (2007), innovation can be observed at the sector, business or project level; innovation is most visible at sector level and least visible at project level. The construction sector is an interlocked system involving many stakeholders, among which are clients who have the potential to act as innovation creators. In this context, clients could spur innovation in construction by:

- – exerting pressure on supply chain partners to improve overall performance (Gann and Salter 2000);

- – helping them to devise strategies to cope with unforeseen changes6;

- – requesting high standards of work (Barlow 2000);

- – stipulating explicit and forward-looking requirements for a project (Seaden and Manseau 2001).

Knowledge provision, operative leadership and dissemination of innovations are also key parts that clients could play in this respect (Egbu 2008).

As previously noted, existing literature on innovation in construction neglects project-level innovations, largely because of difficulties encountered when trying to monitor the various activities carried out by stakeholders in each phase of the project. As Marceau et al. (1999) observe, the management of innovation in construction is complicated by the sporadic nature of project-based production which regularly includes broken learning and feedback loops. For this reason, we believe that a deeper understanding of the different types of innovative activity that occur during a CPLC is necessary to enable their effective application and management, consequently allowing for value creation that could ultimately benefit anybody and everybody.

2.4. The general contractor

Following copious amounts of reading, and after having carried out several investigations in my assiduous search for some real and relevant information about general contractors, I can now resolutely corroborate that the existing academic literature on the matter is quite limited. This is exemplified by the fact that all of my attempts to gain insight into the role of general contractors in general – and in construction management services, specifically – have unfortunately come to a dead end.

However, in order to develop the subject further, I have conducted some further analyses and compiled ample real-world information about general contractors. The focus is on what they do, how they compare to other construction actors and – applying Freakonomics-style thinking7 – what they have in common with music conductors, and why this is important. The following is based on secondary data, taken from specialist magazines, websites and blogs, alongside talks held with peers who – like myself – are experts in the building and construction industry. At various points, I intervene by voicing my own standpoint to explain some technical nuances that would otherwise have remained elusive.

2.4.1. Roles and responsibilities

GCs (General Contractors)8 could assume many different roles and positions when working on a construction project. Naturally, the responsibilities of GCs vary depending on the size and complexity of the project9. Indeed, GCs are responsible for a number of details over the course of a given construction project. Finding the right talent to get the job done is clearly one of their most important tasks, though not the only one. Today, there is much discussion about the varied roles that GCs could play in a project (Figure 2.8). Indeed, there are so many instances of GCs who spread themselves too thinly in an attempt to satisfy the various needs of projects and clients (see Table 2.4). Interestingly enough, a crucial move in that direction is currently taking place10.

By definition, a GC is a stakeholder – an entity or a person – who manages the construction work in its entirety, supervises daily activities at construction sites and ensures all construction works are carried out properly. Moreover, a GC supplies the labor, building materials, machinery, raw materials and all other kit necessary for the successful completion of the work in general. For industry experts, the GC is a “central operator” who provides tailored solutions to clients, and expertly manages worksites, tradespeople, deadlines and budgets11. Typically, GCs are hired via a bidding process and often the lowest bid for the least qualified entity is selected for the job. The GC’s set price is based on the contract terms and the construction drawings. Should the GC spend less than the bid, then they profit on the differential. On the contrary, if the GC bid is over budget, then the project owner would then be over budget as well (at the outset) and would need to adjust it accordingly. This could involve providing extra money to cover the costs, changing project specifications, or reducing the scope; it then becomes apparent why the relationship between the GC and the owner is often regarded as competitive (Yang et al. 2010).

Furthermore, GCs do not always have the required expertise to complete all of the construction work themselves. For this reason, they maintain a network of specialist subcontractors (they have their own construction value chains!). GCs are the big picture thinkers12; they are involved in construction projects from the inception phase to the delivery of the final product, whereas subcontractors, for instance, step in only to fulfill particular tasks: concrete formulation, plumbing, electricity, carpentry, etc.

One of the many roles assumed by a GC is to maintain direct contact with clients to keep them informed about progress being made, as well as with other construction actors (architects, engineers and others) throughout the whole CPLC.

In addition, GCs often handle hiring and are responsible for instructing those new to the job. In any project, there are a number of codes, laws and regulations that GCs must abide by at all times. They must follow applicable labor laws, including organized union contracts under which their staff work and must be aware of safety regulations for various tasks and equipment operators. The GC is therefore responsible for guaranteeing that all of these situations are handled properly, whether that be securing medical attention for an incapacitated worker, locating backup equipment or expediting a supply order. When progress is delayed, the GC must look for ways to get the project back on track. This is imperative because delays in construction projects are typically very costly (Ramanathan et al. 2012).

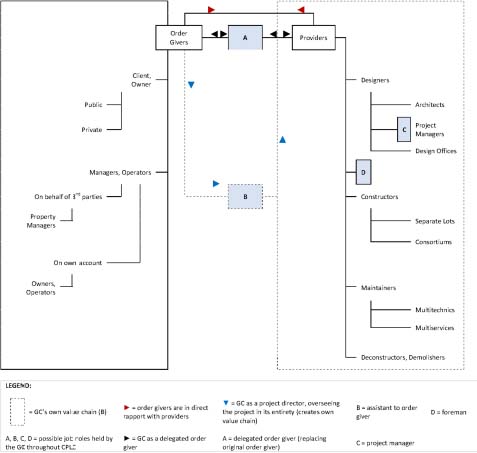

Figure 2.8. Construction sector organigram

(source: created by the author. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

Table 2.4. General contractors’ roles

(source: created by the author. For a color version of this table, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

In terms of the contract to be signed, project owners may possibly add a “no-damage-for-delay” clause, thus shifting the burden of potential delays to the GC. We can therefore summarize by attesting that:

- – it is very complicated to establish a precise definition for the role/s and duties of a GC because of the range of services that they are capable of providing;

- – however, it is quite easy to ratify that GCs are both mavens (experts in the field of building and construction) and connectors (orchestrating the work of all construction actors).

Lastly, it is important to point out that the advent of high-tech (IoT, big data and others), and the increase in smart constructions and initiatives around the world – coupled with the issues the construction sector has been facing in terms of project delivery – have together paved the way for defining (and endorsing) a new job description for GCs.

2.4.2. General contractors versus other industry actors

GCs, in contrast to other construction actors, have the potential to play several roles and hold various positions – A, B, C or D – within the construction value chain. In view of that, their level of contribution to the overall success of construction projects is likely to vary based on whether they are involved at the very early stages, or further down the chain. The challenges faced by GCs are, by the same token, likely to vary based on intervention stage/time. Put simply, the more involved GCs are (i.e. the earlier they become involved) in large-scale construction projects, in particular, the less likely they are to face challenges at later stages. Furthermore, the less likely it is that timings and costs (among other aspects) would alter as the construction work progressed.

As shown in Figure 2.8 – and then expounded in Table 2.4 – a GC’s added value would be hypothetically maximized under scenarios A and B. This is primarily because they will be given the opportunity to create their own value chain and to manage the different parts of the project on their own, in order to meet requirements in the best way possible. Within this framework, GCs would have complete control over all aspects of the project, would manage all construction services as they see fit and consequently be able to deliver the project on time and within budget. If the opposite should happen, however, i.e. should any issues arise (resulting in deviation from the original plan) then they would be the only ones to assume the entirety of ensuing costs. Under scenarios C and D, however, the contribution made by GCs in terms of the success (or failure) of a construction project is only marginal. They therefore cannot be held responsible for any operational snags they might encounter, except for those directly within their mandate.

We continue our investigation by considering the roles of two industry actors, namely: construction managers and project managers, in terms of what they do and how they compare to GCs.

2.4.2.1. Construction managers

A large construction project produces a veritable cacophony as a result of the substantial number of people involved in it. And for those involved to be able to create beautiful tunes together, a conductor is needed for guidance and direction. For owners, attaining the desired outcomes on a full-scale project is a huge challenge that they have to address on a daily basis. Coordinating the many subcontractors, suppliers and other personnel – among numerous aspects – is a balancing act that requires attention and fortitude. We believe that the people who can accomplish these key tasks fall into one of two roles: GCs (General Contractors) or CMs (Construction Managers).

The ultimate goal of both roles is essentially the same, that is, to put all of the pieces of the puzzle together and execute the design according to what the project owner wants and what the regulations demand. Indeed, GCs and CMs have the same objective of completing the project to the satisfaction of the owner13. However, have you ever considered the disparities that exist between GCs and CMs? It may seem as though they have the same job but how similar are their jobs really? Despite the apparent similarities between the two, a GC and a CM go about their roles slightly differently as each has their own set of unique financial structures and duties; thus they each have their own strategies for safe and efficient execution of construction projects in general. Other key differences relate to their organizational structures, how they are selected for projects along with their entry point, as well as their associations with project owners14.

Commonly, GCs and CMs are considered to be the main contractors on the job, bringing with them different apporaches to construction projects. The decision to appoint either one of them – chief conductor of the orchestra – depends upon owner preferences, which could vary on a project-by-project basis. Indeed, for everyone to sing from the same song sheet, in harmony with the owner, seems to be rather fundamental (see section 1.10 for a rogue analogy between GCs and music conductors). But why do project owners tend to favor CMs over GCs? The answer is simple. Owners prefer to work with CMs because of the personal relationships they have developed with them over the years which has resulted in an appreciation of, and familiarity with their work.

Nonetheless, it is not unusual for a GC to act as a CM. In fact, a GC who has handled a few projects for a given project owner and has subsequently established a relationship with that owner, could be asked to work on a new project as a CM. The drive for doing so is less about money and more about trust and a preference for the style and substance of that the GC. This overlap between the two roles, i.e. GCs acting as both a GC and a CM (we believe!) has a best-of-both-worlds benefit. This is particularly true for the owners in that it reduces the possibility of any potentially confrontational exchanges occurring between them and GCs, while upholding the close ties between GCs and their subcontractors15.

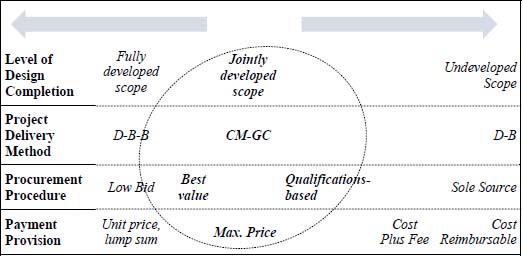

Table 2.5 shows the CM-GC (Construction Manager–General Contractor) project delivery method as an alternative to other methods: D–B–B (Design–Bid–Build) and D–B (Design–Build).

Table 2.5. Project delivery system spectrum

(source: adapted from Gransberg and Shane (2015))

According to Antoine (2017), use of CM–GC and D–B methods has increased significantly in recent years. These methods are hands-on routes for curbing construction project durations, delivering projects more expertly and speedily, and establishing early cost certainty during project delivery. Equally importantly, Le Masson and Weil (2009), and Rosati and Conti (2016) explain that the CM–GC method – being either best value or qualifications-based – allows owners, designers and/or architects, as well as GCs, to work together to tweak the scope of construction projects and make rational project management decisions.

In addition, Flyvbjerg (2014) acknowledged that, under the CM–GC method, GCs are not nominated – at least not anymore – through passive bidding processes but based on valid credentials, past performances and success records.

2.4.2.2. Project managers

In construction, project completion is always the ultimate goal; however, achieving this in an efficient and timely manner is sometimes challenging. For this reason, a PM (Project Manager) is often required and hence, we ask: What do PMs actually do? And how do they compare to GCs?16 Both GCs and PMs play a key role in construction projects. While PMs operate at a slightly higher level, coordinating the different entities involved in the project, GCs also play a coordinating role among different employees, specialists and subcontractors they work with to ensure project success. Thus, while both actors carry an obligation to bring together the different bodies that operate under them, GCs and PMs function at different levels in the construction management process. This can be a source of confusion for people trying to figure out what sets these two management positions apart.

For small- to medium-sized construction projects, the owner (client) could possibly choose to work with a GC who will not only perform much of the construction work but will also help coordinate between different parties involved in the process and serve as the main point of contact for the client. Nevertheless, according to the status quo, for larger projects the coordination of different entities involved in the project would be the duty of the PM.

Despite some similarities in their roles (as you may have guessed by now!), PMs and GCs remain poles apart. Generally, PMs are accountable for high-level coordination of construction projects. Unlike GCs, who are chiefly responsible for the actual physical construction of a project (partially or wholly), PMs work closely with all parties involved in a project to ensure that the owner’s goals have been met, the project has stayed within budget and the project is delivered on time. In their role PMs serve as team leaders and primary liaisons with the client. As for clients, they tend to work closely with a project management team so that the scope and goals of a project are clearly defined; in other words, developing a strategic plan. When creating a strategic plan, the PM and the client join forces to define the scope of the project and the desired timeline and budget. Aside from drafting a budget that aligns with the client’s expectations, PMs are also responsible for implementing that budget and ensuring the project remains on (or below) budget throughout the whole CPLC. This is key as because large construction projects are well known for going over-budget.

Table 2.6. General contractors vs. construction managers vs. project managers17

| GCs | • Typical business entities; • have their own complement of staff in the form of a pool of subcontractors; • specialize in certain types of construction and in certain construction sectors; • chosen via bidding processes and involved in construction and in the daily direction and operation of projects; • ensure that all works are completed properly and on time; • complete physical works onsite with the help of their teams of construction workers; • could act as CMs and be involved in construction projects early on as an advisor (this is factual given there is an established rapport between them and the owners; in this case, GCs no longer need to submit competitive blind-bid proposals but realistic ones based on insight into the development of the design). |

| CMs | • Could be an individual, group of people or an organization; • selected based on qualifications and experience (rather than bids); • pay is fee-based thus they receive a percentage of the total project cost (no competition for profits like with GCs); • involved at the very beginning of the project providing input on the design and working with subcontractors to provide accurate costs and timeframes; • maintain collaborative, win-win rapport with the owners and tend to work exclusively for them; • on staff with CMs are estimators, accountants or other professionals with duties that come into play before, during and after a project; • are involved during pre-construction and work with the design architects; • work with onsite managers who handle the projects during construction; • advise owners and lead construction workers; • responsible for setting/keeping to schedules and monitoring finances. |

| PMs | • Involved in all aspects of the construction project, including pre-construction activities, construction administration and post-construction; • understand client objectives and priorities and ensure that all project consultants are in line with these objectives; • manage staff according to target capacity, budget, timeframe and quality of project; • on-site throughout the entire project and, unlike GCs and CMs, they oversee it from pre-construction to closure; • in some cases they supervise CMs and/or GCs on behalf of clients. |

Ceteris paribus, a competent PM would ultimately add value to a given construction project by defining a comprehensive budget that incorporates all expenditures, capital and operational, and by sticking to that budget over time. Furthermore, PMs oversee the execution of projects and assemble the teams needed to complete them. Assembling teams is often carried out by issuing a request for proposal to the entities concerned: architectural, engineering and general contracting companies. During this process, PMs are expected to perform a certain level of due diligence to ensure the companies chosen have experience with projects of a similar type, as well as the necessary qualifications and KB (Knowledge Base)18 to successfully complete the assigned project. Subsequently, PMs oversee contract negotiations to guarantee that the scope of the project, budget and timeline are clearly understood by all parties in the project team (see Table 2.6).

2.5. How do general contractors resemble music conductors?

Now we turn to music! Conducting is the art of guiding the concurrent performance of several players19 through hand gestures, usually with the aid of a baton20. In other words, conducting is a means of communicating directions to musicians during a performance21. Actually, there are many formal rules that state how to conduct properly, as well as a range of conducting styles that tend to vary according to the education and complexity of the conductor. In general, a conductor’s main aim is to unify performers, set the tempo, ensure well-timed entries by ensemble members, execute clear beats, listen analytically to shape the sound of the ensemble and control the pacing of the music.

Communication (as you might expect!) is nonverbal during live performances and yet it is verbal during rehearsals; conductors may stop the playing of a piece to orally request some style changes or ask for adjustments in the tone of a certain section.

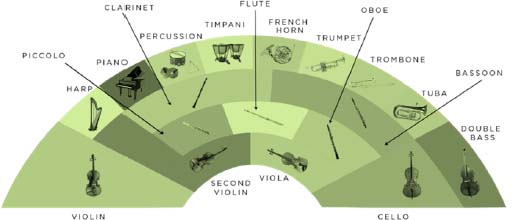

In an orchestra, the smallest instrument is the piccolo which is a half-size flute. The largest family of instruments is the strings and these come in different sizes: the violin (the smallest), followed by the viola and the cello and then the double bass (the largest). Figure 2.9 shows how an orchestra is arranged; the first chair violinist, usually regarded as the best, sits to the music conductor’s left, adjacent to the audience. They are the “concertmaster” – the leader of the violin section – who, in smaller orchestral settings, has the potential to lead the ensemble independently hence, to act as a music conductor.

NOTE.– We hope by now that you are able to detect the hidden similarities between the roles played by conductors and concertmasters (owners, PMs, CMs and GCs), and how these roles will likely change according to the size of the orchestra (construction project)!

Figure 2.9. Sections of the orchestra22

In the music industry, a conductor is occasionally referred to as a director or chief conductor. Other conductors, usually those who lead choirs, are at times referred to as choral directors, chorus masters or choirmasters. Conductors of concert (military or marching) bands, on the other hand, hold a number of titles, for example, band directors or bandmasters. And senior music conductors are routinely called maestros. BOOM! GCs are given several names too: main contractors, prime contractors, head contractors and others.

Now that we know just a little bit more about orchestras and music conductors, we may proceed by asking the following questions23: Why are orchestras structured in the way that they are? Why are the oboes and tubas positioned at the front? Why do flutes and violins not swap positions? Why do trombones and French horns not sit right up front with the music conductor? In fact, (we believe!) there is a good reason for why pretty much everything we experience (in life) is the way it really is; the seating arrangements of an orchestra are no exception. In an article24 for The Florida Times-Union, Courtney Lewis – the Jacksonville Symphony Music Director – gave a concise explanation for why players sit where they do. According to Lewis, “orchestras owe their present-day configuration to two phenomena (surprisingly!): industrialization and urbanization [...] The current seating arrangements are a fairly contemporary development”.

Until the 20th century, the violins – first and second – were seated opposite one another, for the most part to create a stereo effect with the two sections playing off one another. A few years later, the influential conductor – Leopold Stokowski25 – appeared. Stokowski was an alchemist; he tried seating the orchestra in every conceivable way in an effort to find the perfect amalgam of resonances. This is actually the responsibility of the central operator who tries to bring all construction actors together, in order to create beautiful melodies rather than mishmashes of conflicting sounds.

But it was only in the 1920s that Stokowski made a change that stuck. Trusting that all violins should be placed together to help the performers hear one another better, he proceeded by organizing the strings from high-to-low and from left-to-right. The Stokowski Shift – as it then became known (a new orchestral structure)26 – was espoused by orchestras all over America. In the UK, the same arrangement was favored a few years later, leading to its general adoption across the country. This structure, though unpopular at first, did gain influence and power over time. And the outcome? (You guessed it right!). Composers from around the world started writing pieces of music that took advantage of this arrangement. (Hooray! New business structures seem to be catching.)

Let us refer back to conducting; a conductor must understand all the elements of musical expression (tempo, dynamics and articulation) and have the ability to communicate them effectively to an ensemble. This is also true for those assigned to lead construction projects! The ability to communicate nuances of phrasing and expression through gestures is also a prerequisite to becoming a competent conductor27. This is indispensable because dynamics in music are often signaled with hand gestures and communicated by the size of the conducting movements, with larger shapes representing louder sounds. Moving forward, the indication of entries – that is, when a performer (or section) should begin playing – is called cueing (corresponding to when-and-how each construction actor is supposed to intervene throughout a CPLC). A cue indicates the exact moment of the coming beat so that all players responding to the cue can start playing in chorus. A cue is vital for indicating when performers should change to a new note. And cueing is achieved by engaging the players before their entry and executing a clear preparation gesture, often directed towards the specific players28. (The latter statement explains why strategic project management plans are so important.)

To sum up, conductors act as leaders of the orchestras they conduct; they choose the works to be performed and study their scores29. Nevertheless, within particular frameworks, they could also handle a series of executive tasks (e.g. schedule practices, plan concert seasons, hear auditions and choose participants, as well as promote their ensemble in the media). Indeed, the role/s that a music conductor could potentially play vary greatly between different conducting positions and ensembles. (We hope you are able to keep count of the numerous similarities between GCs and conductors.)

In some cases, a conductor could be the musical director of the symphony, choosing the program for the entire season. In other cases, the conductor could attend some or all of the auditions for new members of the orchestra to ensure that the runners have the required playing style and tone, and meet the highest performance standards. Within different settings, conductors could be hired simply to prepare a choir for a number of weeks, which would then be directed by another conductor. A number of other conductors, on the other hand, could have a substantial public relations role, giving interviews to the local news channel and appearing on talk shows to promote the approaching season’s concerts. It is clear that music conductors, very much like GCs, play different roles and assume different positions along the musical value chain.

Once again, we wonder: Why is there even a music conductor at all?30 Traditionally, all orchestras played without conductors and were directed by concertmasters. It was only at the start of the 19th century that orchestras became big enough for a conductor to be necessary. Indeed, year after year, orchestras have turned into very large affairs. Similar to stakeholders involved in large and complex construction projects, every musician in a full-scale orchestra could have differing ideas in terms of cues, tempo and how best to play their instrument. Therefore, the main purpose of a music conductor is to interpret the music and allow the performers to get through the piece being played seamlessly, without stopping. Furthermore, a conductor ensures that all instruments are impeccably orchestrated so that none of them ends up being drowned out.

Before closing, let us first imagine how the preceding paragraph would read (or sound!) if we were talking about GCs rather than conductors. By swapping just a few words only, we get the following narrative:

Traditionally, all construction projects were administered without GCs and were directed by project owners. It was only recently that construction projects became big (smart) enough for a GC to be necessary. Indeed, year after year, construction projects have turned into very large affairs. Similar to performers in contemporary orchestras, every stakeholder in a full-scale construction project could have differing ideas in terms of planning, scheduling, budgeting, and construction management services. Therefore, the main purpose of a GC is to oversee construction works and allow for stakeholders to get through the project being built seamlessly, on time and within budget. Furthermore, a GC ensures that the tasks fulfilled by construction actors are impeccably orchestrated so that none of them ends up being drowned out.

Astonishing, right? In any case, regardless of whether you appreciate this fabricated reconciliation between GCs and music conductors, no one could refute that the resemblances between the two are noticeably evident (see Table 2.7).

Table 2.7. General contractors vs. music conductors

(source: created by the author)

| General Contractors ▼ | Music Conductors ▼ | |

| Involved in | All types of construction projects, including large ones too (e.g. smart constructions) | Symphony orchestras and philharmonics, primarily large ones |

| Other given titles | Main contractor, primary contractor, prime contractor, and others | Chief conductor, main conductor, senior conductor, maestro, and others |

| An expert | Yes | Yes |

| A connector | Yes | Yes |

| Main duties | • Supervise and manage the execution of construction projects | • Ensure the accurateness of musical pieces and symphonies performed |

| • Communicate with stakeholders at all times to keep them informed of progress and potential snags | • Communicate with musicians at all times during performances using hand gestures to keep them orchestrated | |

| • Have their own networks of construction actors | • Recruit instrumentalists | |

| • Conduct pilot tests and feasibility studies | • Run rehearsals and auditions | |

| • Direct and (co-direct) projects (scenarios A & B) | • Conduct (and co-conduct) concerts | |

| • Decide on construction project management processes | • Select entire music programs | |

| • Ensure fair interplay between all stakeholders | • Make sure all performers are playing harmonically | |

| • Handle non-technical tasks (e.g. scheduling, planning, following-up with clients) | • Handle managerial tasks (e.g. scheduling, planning, interacting with the audience) | |

| Objectives | • Customer satisfaction | • Audience satisfaction |

| • Deliver project on time and within budget | • Deliver great performance by setting the right tempo and shaping the sound of the ensemble | |

| • Bringing construction actors together to create an interlocked working system | • Unifying performers to create one sound, one orchestra |

2.6. Conclusion

Thus far, we have shown how the construction value chain has evolved with the wave of innovations in construction, paving the way for the involvement of a new actor, the central operator. The latter is to act as a conductor, harmonizing the performance of all industry players so that large-scale, smart developments end up being impeccably built. Following Stokowski’s Shift, we have also established that it is inconceivable that a single value chain can fit all types of projects; hence the need to conceive new ones (one or more) that could establish a better interplay between instrumentalists, including ICT companies and end-users. Similarly, we have evidenced that business models, which endure for longer than construction project processes, are highly influential when it comes to companies’ long-term business success. Additionally, we have ascertained that GCs are both mavens and connectors in the field of construction, with their own support networks. Much like music conductors, GCs are frontrunners with the ability to play various roles and assume different positions across the construction industry’s value chain: CMs, PMs, assistants to project owners and delegated project owners.

- 1 Two sides of the same coin? The differences between general contractors and construction managers. Available at: https://jobsite.procore.com/construction-manager-vs-general-contractor-roles-differences/ [Accessed March 15, 2021].

- 2 2018 Global status report – Towards a zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. Available at: https://www.worldgbc.org/news-media/2018-global-status-report-towards-zero-emission-efficient-and-resilient-buildings-and [Accessed March 15, 2021].

- 3 Also known as the online contractor – the equivalent of a general contractor – the term used in this book. Sections 2.4 and 2.5 provide more insights into the roles played by general contractors. A detailed explanation of the general contractor business model for the construction and management of smart cities is available in Chapter 4.

- 4 Top five project management phases. Available at: https://project-management.com/top-5-project-management-phases/ [Accessed March 15, 2021].

- 5 Ibid.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 For more information, see: http://freakonomics.com/archive/ [Accessed March 15, 2021].

- 8 Sometimes referred to as: Main Contractors.

- 9 Important facts you need to know about a general contractor. Available at: https://construction.laws.com/general-contractor [Accessed March 10, 2021].

- 10 Who is a contractor (definition)? Available at: https://www.letsbuild.com/blog/contractor-role-duties [Accessed March 10, 2021].

- 11 What is the role of general contractors in construction work? Available at: http://www.accconstruction.ca/what-is-the-role-of-general-contractor-in-construction-work/ [Accessed March 10, 2021].

- 12 Interview with Raymond Vigneau, owner of Metal Building Contractors, Inc. Available at: https://home.howstuffworks.com/home-improvement/construction/planning/why-hire-a-contractor1.htm [Accessed March 10, 2021].

- 13 Two sides of the same coin? The differences between general contractors and construction managers. Available at: https://jobsite.procore.com/construction-manager-vs-general-contractor-roles-differences/ [Accessed March 12, 2021].

- 14 Construction managers vs. general contractors: What is the difference? Available at: https://esub.com/construction-manager-vs-general-contractor/ [Accessed March 12, 2021].

- 15 What is the difference? General contractors vs. construction managers. Available at: https://www.suretybondsdirect.com/educate/general-contractor-vs-construction-manager [Accessed March 12, 2021].

- 16 General contractor vs. project manager. Available at: https://gillilandcm.com/2018/12/06/general-contractor-vs-project-manager/ [Accessed March 12, 2021].

- 17 The difference between a project manager, construction manager and general contractor. Available at: https://watchdogpm.com/blog/the-difference-between-a-project-manager-construction-manager-and-general-contractor/ [Accessed March 12, 2021].

- 18 A KB is a technology used to store complex structured and unstructured information used by a computer system.

- 19 A full-scale orchestra playing a symphony comprises over 90 musicians, while a smaller orchestra playing a chamber piece, for instance, includes a maximum of 45 musicians.

- 20 Louis Spohr claimed to be the first to introduce a conducting baton to England in 1820 but reports indicate that Daniel Turk conducted the Halle Orchestra with a baton in 1810, 10 years earlier.

- 21 The conductor of an ensemble. Available at: https://www.liveabout.com/what-is-a-conductor-2456662 [Accessed March 14, 2021].

- 22 Sections of the orchestra. Available at: https://www.thinglink.com/scene/682291240225472514 [Accessed March 14, 2021].

- 23 Why is the orchestra seated that way? An explanation. Available at: https://www.wqxr.org/story/why-orchestra-seated-way-explanation/ [Accessed March 14, 2021].

- 24 Ibid.

- 25 He served as the music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

- 26 The equivalent of a new business model – or value chain – in construction.

- 27 What is the career path to becoming a conductor? Available at: https://www.connollymusic.com/stringovation/career-path-to-become-a-conductor [Accessed March 14, 2021].

- 28 What is a music cue? Available at: https://www.mediamusicnow.co.uk/information/glossary-of-music-production-terms/what-is-a-music-cue.aspx [Accessed March 14, 2021].

- 29 An orchestral score shows all parts of a large work, with each part on separate staves in vertical alignment, and is for the use of the conductor. Thus, the conductor could see at a glance what each performer should be playing and what the ensemble sound should be.

- 30 Why do orchestras need a conductor? Available at: https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/instruments/conductor/what-does-a-conductor-actually-do/ [Accessed March 15, 2021].