How to focus your language for extraordinary results

In the last chapter you read about a number of ways to get people to cooperate in helping you reach your goals. Being persuasive is a crucial skill and the strongest persuasion tools are your words. This is another skill you already have, but perhaps are not fully aware of how to use it consistently. By the time you’ve finished reading this chapter, you’ll know how to apply this skill whenever you need it.

You’re already a persuasive communicator

If you doubt that you already have the ability to use focused language, consider:

- Have you ever convinced your parents that you were just at a friend’s house, studying, when actually you were (fill in the blank)?

- Have you ever convinced anyone to go out with you? To marry you?

- Have you ever stopped a child who was about to do something dangerous?

- Have you ever been the winning candidate in a job interview?

In those kinds of situations we all tend to be persuasive because we are very clear and focused on the outcome we want. Instinctively we establish rapport with the other person and use whatever approach we feel will be most likely to succeed. By learning how to focus more of your communication like this, you will gain a powerful success tool.

The problem with most conversations

We like to think of conversations as exchanges in which we listen to the other person and share our thoughts and feelings with them. It should be easy, yet often we leave a conversation or business meeting feeling frustrated that the other person didn’t seem to understand. The other person leaves feeling the same way. Why is it so difficult?

One problem is that we tend to ignore the reality of human communication. Let’s take an example: George and Bill are colleagues. They run into each other at the water cooler on Monday morning, and George notices that Bill has a bit of a tan.

George: Hey, Bill, got some sun, eh?

Bill: Yes, Jane and I took the boys to the lake. First time we’ve been camping together this . . .

At this point, George has heard the trigger word “camping” and starts to think about what he wants to say on the subject. The fact that Bill is still talking is convenient, because it gives George time to think.

Bill: . . . other than the outside toilets, ha ha. But . . .

George is ready. He interrupts.

George: I used to go camping all the time when I was young. My dad was a Scout Master, so we could . . .

Bill is slightly annoyed that George has interrupted – after all, Bill hasn’t got around to telling him yet about the fish he caught. Oh well, George will have to take a breath sometime . . .

George: . . .all those merit badges, I still have them somewhere, I’m not sure where. [He takes a breath.]

Bill is more diplomatic than George, so he decides to make a link between what George has just been saying and what he wants to say:

Bill: You must have done a bit of fishing in the Scouts, eh? This weekend, I caught . . .

And so it will go on. Most conversations are not a dialogue, but intersecting monologues. You are the star of your own life, and the others are merely supporting actors. Of course in the other person’s life, they are the star, and you are merely the supporting player. We’re all working from different scripts. No wonder communication can be difficult!

Let’s look at some ways you can use language and associated behaviours to communicate more successfully. In each case, I’ll give concrete examples, because “communication” is an abstract word – it only really takes on meaning when you know what you want to communicate, and to whom. Once you know that, you can decide which “how” will work best. These techniques work in family life, friendships, counselling and business. As you read, you might like to consider in which areas of your life it will help you the most to use them.

THE MYTH OF MARS AND VENUS

In recent years it has been accepted that women talk more and interrupt less often than men. Also that women talk more about feelings and relationships while men talk more about facts, and that women’s conversation tends to be cooperative while men’s tends to be competitive. However, when psychologist Dr Janet Hyde, of the University of Wisconsin in Madison, conducted a metaanalysis of studies of male–female communications she found that there is very little difference in the quantity and quality of male and female talk.

“The Gender Similarities Hypothesis”, American Psychologist, September 2005

Make a connection with the secret of rapport

One of the common phrases people use to indicate there is a rapport between them and another person is to say, “We are on the same wavelength”. When there is this kind of connection between you, it’s much more likely that the other person will do what you want them to do. While we seem to connect automatically with some people, it’s also a skill you can learn and use to your advantage.

Research reveals that rapport seems to be based primarily on similarity or the perception of similarity. The similarity may only be in the area that applies to the situation at hand. The person you enjoy going to football games with because you share a fanatical interest in sports, for example, may not share your interest in old films; but while you’re at the game or discussing football, you two have great rapport.

As this implies, you can establish rapport by finding an interest in common with the other person. And what is each person’s greatest interest most of the time? That’s right: themselves. Therefore, you can establish rapport with just about anyone by taking a genuine interest in them. Let me stress the word “genuine”. A real interest is much more rewarding to both parties than a feigned one. Besides, in my experience only psychopaths and actors are really good at faking it.

When are the times you might want to establish rapport? Often it’s when you’re meeting someone new and you want them to be receptive to your message. Your message might be that you find them attractive and want to go out with them, or that you have a wonderful product they should buy.

LEARNING TO LISTEN

If you find it difficult to really listen, try the following:

- In your mind, paraphrase what the other person is saying.

- Rather than trying to formulate an answer, try to assess how the person feels about what they are saying.

- Set yourself a period of time, maybe just five minutes to start with, to listen intensively. Gradually increase the periods until it becomes automatic.

In all situations, there tends to be a “breaking the ice” period, and this is when establishing rapport is most important. First, break the pattern illustrated in our sample conversation between Bill and George, by actually listening. Instead of letting trigger words send you into yourself (at which point you will be only half-listening), stay with the conversation. Hear the words, but also watch the other person for non-verbal clues to how they feel about what is being described. Give feedback, both verbal and non-verbal (head nodding, smiling, etc.), to show that you understand and are in synch.

Once you start really listening, it’s not as hard as it used to be to find the other person of genuine interest. Let’s use the example of meeting a potential client. Shift your focus from your own desire to sell to wanting to understand the person you are dealing with. Ask some questions and listen to the answers. If there is a good match between what they need and what you’re offering, it will be a natural progression to talk about your product or services.

Establish greater rapport by matching their language

Listening will also give you useful information for a rapport strategy that comes from the field of NLP (Neuro Linguistic Programming). The technique is to match the person with whom you are dealing. One of the things you can match is the language they use to represent their world.

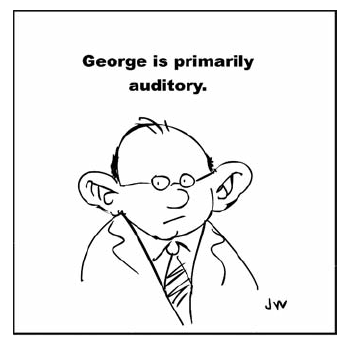

The main representation categories are visual (pictures), auditory (sounds) and kinaesthetic (feeling). If you listen to someone talk, you will find that they tend to use words from one of these categories more than from the others.

- A visual person will say things like: “That’s clear” or “I see your point” or “Give me some time to look at that”.

- An auditory person will say things like: “I heard what you’re saying” or “That rings a bell” or “I like the sound of that”.

- A kinaesthetic person will say things like: “I have a rough idea” or “Those are pretty heavy numbers” or “My gut instinct is that you’re right”.

Most people will use a mixture and some will also use phrases that are gustatory – relating to taste – or olfactory – relating to smell, but typically one of the above three predominates. For practice, you can listen for these when watching TV interviews.

If you then match the other person by using language with the same orientation, the two of you will be more in synch. If addressing a group, use all the categories; if you use only your own favourite one, some of your listeners will not feel on the same wavelength.

Practise using the representational systems

To see, tune into, or get a feeling for this, take a moment to consider your own preferences. If you’re not sure, mentally describe something or explain something you do. You’ll soon notice some terms that tip you off as to which of the categories you prefer. Write down your preferred representational system (visual, auditory or kinaesthetic):![]()

Now repeat the description in your mind but this time work in some terms that come from one of the other two primary systems. For example, let’s say you’re primarily visual and your first description is something like, “When working with a new client, I try to see what they really want from the process”. If you then switch to using auditory terms, you might instead say something like, “When working with a new client, I listen for what they really want from the process”. If you switch to kinaesthetic mode, it could be, “I try to get in touch with what they really want”. Jot down your alternatives here:

Guiding a conversation by pacing and leading

There is another NLP language concept, pacing and leading, that is useful in establishing rapport and also in helping change a negative conversation into a positive one. Let’s take a personal example: a friend calls you up and the conversation goes like this:

Other person: I’m so depressed!

You: Cheer up! The sun is shining, the birds are singing, you should be happy to be alive!!

Not likely to be effective, is it? When you counter one extreme with another extreme, there is no change. If anything, the other extreme just gets more extreme. In our example, the other person now has another reason to be depressed: you are totally insensitive to their feelings. Let’s try it again:

Other person: I’m so depressed!

You: [sympathetic tone of voice]: What’s the matter?

Other person: I’ve gained back two pounds this week. I’m such a weakling!

You: Dieting is so difficult.

Other person: I had three business dinners last week, that’s what did it.

You: Hmmm, yeah, it’s hard not to eat the same things everybody else is eating. Any business dinners next week?

Other person: Only one. I’m taking out a potential client.

You: Japanese food can be pretty healthy and light in calories. Do you think they might agree to a Japanese restaurant?

Other person: Good idea. I can ask.

This is a bit compressed, but you can see the pattern. You start out by expressing empathy with your tone of voice as well as your words. Then you look for a genuinely more positive aspect to focus on (in this case it’s that there’s only one business dinner next week; in real life, it may take a bit longer to find the positive aspect). Then you move forward into looking at some useful alternatives. At times, this last step may not be necessary; the other person may already have alternatives and the only thing needed is a little sympathy.

PERFECTING YOUR PACING

If you have trouble pacing someone’s mood, try matching their posture and how they hold their heads (subtly, of course). Then very gradaully change your posture to more closely match the mood you’d like to encourage in the other person. If you do it well, they will also begin to change their posture.

Here’s another brief example, this time a sales situation:

Customer: These cars are all too expensive.

Salesperson: Not really. They’re excellent value!

Again, not likely to succeed. Here’s an alternative:

Customer: These cars are all too expensive.

Salesperson: It seems like everything is costing more, doesn’t it?

Customer: I’m going to have find something cheaper.

Salesperson: Frankly, that might be a good idea, in the short term. These cars will only save you money in the long run.

Customer: What do you mean?

Then the salesperson might discuss depreciation figures, fuel consumption, the financing plan or whatever else makes the car excellent value.

First you establish that you’re a friendly force who understands their predicament. Then you gradually refocus the conversation. Watch for signs that you’re going too fast for their comfort. If so, backtrack a step, pace them where they are, and then take a smaller step forward. Eventually you will bring them around to a version of the conversation that supports your goal.

Persuade through the power of reframing

Reframing means looking at something in a different way. It’s similar to using metaphors and stories, in that the reframed version is like a new story about the same thing. For instance, if the glass is half empty, it must also be half full. Here’s an example of reframing in a conversation:

Maria: There’s a personal development workshop my sister has been raving about, and it’s on again this weekend. Do you think you might want to go?

Ted: I don’t know. Where is it? And when?

Maria: This weekend. It’s in Birmingham. We’d have to leave London at 6 a.m.

Ted: Be up at 6 a.m. on a Saturday?! Forget it!

Maria: Yes, that’s pretty early. Of course it would only be the one morning, and the weekend could change your life.

Ted: Change my life? How?

The trigger here was 6 a.m. Probably Ted immediately made an internal picture of trying to get up at 5 a.m. and didn’t like it. Then Maria reframed it by putting it in a different, much bigger context: getting up early one day to change one’s life. That was enough to make Ted interested again and ask for more information.

An example parents will be familiar with is a young child saying she doesn’t want to go to school. You may be able to reframe the idea of getting up by saying something like, “I bet the other kids will be having fun today in art class, doing finger painting. And I guess your best friend Susie will be OK on her own at lunch – she’ll probably find somebody else to play with.” Suddenly the need to get up is part of a much bigger picture and will be more appealing.

REFRAMING WITH QUANTITY

One of the typical ways that advertisers use reframing is to describe something large in terms of small chunks (“costs no more than a cup of coffee per day”), or something small in terms of a larger aggregate (“by the end of the year your savings will allow you to buy Christmas presents for the whole family”). If you are trying to persuade someone of something that involves a quantity of time or money, consider which way of framing it will be more effective.

Reframing practice

Think of one example of something you’d like to persuade someone else about. It could be a personal or business situation. Jot it down here:![]()

Now think of one way you could reframe this that would make it more appealing to the person you’re trying to convince:![]()

Focus your communication with metaphors and stories

All the great religious works, like the Bible, use metaphors and parables to make their points. Telling a story can be extremely powerful. Let me give you an example – my favourite Zen story:

An elderly monk and a novice were walking through the countryside. They came to a raging river and saw there a young woman who was afraid to cross. The elderly monk took her upon his shoulders and carried her across. She thanked him profusely and they went their separate ways. For the next three days, the young monk was disturbed, and he became more and more agitated. Finally the old monk asked him what was the matter. “Master,” he said, “you know we are forbidden to have physical contact with women!” “Ah,” said the old monk, “that woman at the river. I put her down three days ago . . . are you still carrying her?”

I defy anyone to come up with a more elegant and powerful way to make the point!

The great thing about a metaphor is that the listener has to make sense of it, to relate it to their life or the situation being discussed. Often this happens on the subconscious level and thus goes more deeply into their awareness.

Public speakers have long used metaphors and metaphorical stories (look at the speeches of Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, or any of the great orators), and metaphors are still powerful because they are entertaining as well as informative.

A metaphor need not be a whole story, it can be simply a phrase or a sentence. Let’s say a colleague feels that negotiations have hit a standstill and there’s no point in going on. You could say something like, “Yes, it feels like we’re hitting a brick wall. I wonder if there’s a way to tunnel under it.” Just a simple statement like that may give your colleague the idea not to stick to the same strategy, but to consider trying something different.

The next time you need to make a point but feel that making it directly might lead to resistance, construct a metaphor and drop that into your conversation instead. Avoid the temptation to follow the metaphor with your explanation of what it means, or else you’ll negate its value.

Practise with a metaphor

Think of a message you’d like to get across (it can be the same one you used when practising with representational systems or a new one). Write it down here:![]()

Now think of a metaphor, a story, or just a phrase, that might make the situation easier for someone else to understand or relate to. If you have trouble thinking of one, consider whether a well-known folk or fairy tale might give you some material. “The Three Little Pigs” is about preparation, for example, and “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” is about finding just the right solution. Write it down here:![]()

![]()

![]()

Defuse opposition with the Three Questions technique

Naturally you will sometimes encounter opposition to your ideas. The goal of the Three Questions technique is to prevent opposition from hardening too quickly and to give you information you can use either as a basis for changing your own position or for bringing the other person around to yours.

This technique is simple: before opposing any statement by another person, ask at least three questions.

Let’s run through an example of a screenwriter in a meeting with a producer:

Producer: The ending of your script doesn’t work for me.

Writer: Everything in that script leads up to that ending!

Producer: Yes, but it doesn’t work.

Writer: You’re the first person to say that! Everybody else loves the ending.

I’m probably creating a stroppier writer here than producers normally encounter. But you can see that this is a familiar pattern and that it isn’t getting them anywhere. Let’s see how three questions might help:

Producer: The ending of your script doesn’t work for me.

Writer: I see. What, specifically, do you feel doesn’t work?

Producer: I just don’t think the woman would act that way.

Writer: Hmm, that’s interesting. What does she do that you don’t find plausible?

Producer: She picks up the gun and goes out on to the street – I mean, how does she suddenly know how to use a gun?

Writer: I see, so you feel that we haven’t laid the groundwork for that action?

Producer: That’s right!

Writer: Well, maybe there’s something we can do earlier in the script to set up that she’s able to use a gun – maybe her father used to take her hunting, or she did a self-defence course or something like that.

You may be surprised at how often what the other person says first isn’t really what they mean. Asking at least three questions will help you get to the bottom of their meaning, and then you can respond to that. Also, asking three questions stops the conversation from immediately turning into a battle. You will come across as very reasonable, and that in itself may be helpful in further discussion.

How to break a block

There are times when, with all the goodwill in the world, you will find that you and the person with whom you’re speaking just can’t agree on some point. What to do then? Move up one or more levels to the point where you do agree, and then generate additional alternatives. In other words, move the focus of the conversation away from the point of disagreement, to a point of agreement, then on to a new point of agreement.

Let’s take a business example: your firm’s PR agency made a mess of a campaign. You want to fire them and bring the function in-house, while your colleague wants to give them a strong reprimand but give them another chance.

Backing up one step, what was the last thing you agreed upon? Perhaps it was just that the PR company did a very poor job and didn’t liaise closely enough with your company before releasing information to the press.

Now start generating alternatives that would deal with the problem that you do agree needs to be dealt with: maybe you could set up a formal system of clearing information; maybe you could ask one of the PR company employees to work from your premises; maybe you could assign one of your employees to liaise daily with them, or put them on their premises. You generate responses to the problem until you find one that is acceptable to both of you.

The other benefit of this technique is that by stepping back to a level on which you do agree, you defuse the hostility that can be present when two people are both defending their ground.

You say yes so they say no (how to cope with polarity response)

Anybody who has had dealings with a four-year-old already understands the concept of polarity response. It means that whatever you say, the other person will automatically say the opposite. It’s a strategy for rebelling and testing limits; most people go through it when they’re three or four and again when they’re teenagers, but some stick with it all their lives.

I once worked with a woman who had the most extreme example of polarity response (combined with general negativism) that I’ve ever encountered. No matter what anybody proposed, she was against it and could instantly generate 22 reasons why it would never work. We eventually discovered a constructive alternative to killing her! We realised she was actually a good source of information about what might go wrong with our plans. Among those 22 reasons, there were a few that were not just general paranoia but were actually valid, and if we headed those off we could strengthen our plans.

Notice what happened: we reframed our perception of her from being a negative doom-sayer to being someone who could give us some valuable information. This changed our relationship with her (not to say that she wasn’t still annoying . . .) and helped our work. This is a good example of how reframing isn’t just about image or feelings – it can have a concrete result.

In some cases, however, you need to get someone who has habitual polarity response to agree to something. How can you do it? Here are two strategies:

- Give them several alternatives, all of which would be acceptable to you, and ask them to choose one. They’ll probably hate all of them but you can still get them to choose the least objectionable.

- Take the position opposite to, or at least different from, the one you really support. The other person will oppose it and you can let them convince you. Don’t give in too easily, though. A friend used this when she was visiting a relative in hospital who responded negatively to any positive statement (for example, “You’re looking better today” would lead her to say, “Oh, but I feel much worse”). Finally my friend started being even more negative than the patient (“You look at death’s door today!”) which shocked the patient into protesting that she didn’t feel that bad.

Focus your self-talk

Equally as important as what you say to others is what you say to yourself. Most of us have an internal running commentary. Often this is shockingly judgemental and harsh. We say things to ourselves we would never say to a friend or colleague. Just as you can now listen more attentively to what others say, you can begin to pay more attention to what you say to yourself – and to challenge it when it is harsh or otherwise not constructive. You can use many of the same techniques you’ve read about in this chapter. For example, when you make a mistake, rather than getting down on yourself for it, reframe it. Put it into perspective with everything else you’ve done. Making a mistake does not make you a dummy or a failure – it makes you a human being. We all make them, and when we realise we’ve made them we have the opportunity to choose between punishing ourselves or simply learning something.

Think back to a time recently when you made a mistake. What did you say to yourself about it? If you can’t remember, you can still make an educated guess:![]()

Would it have been more constructive to say something else? If so, write it here:![]()

Making this change permanent requires some practice. A few times a day check what you’re saying to yourself and immediately correct anything that is harsh. Over time you will create a new habit of listening to a constructive inner guide rather than a harsh inner critic.

What’s next

All the techniques in this chapter work best when you know what you want to communicate and when you respect the other person’s reality. Then the stage is set for you to focus the communication in the way that helps you achieve your goals. One of the things that makes it hard to focus is information overload. In the next chapter, you will discover techniques for taming that phenomenon.

Website chapter bonus

At www.focusquick.com you will find a video interview with communication expert and therapist Philip Harland about how to communicate more effectively with others and yourself using a technique called “clean language”.