How to (finally) beat procrastination

Procrastination is the natural enemy of focus. When we procrastinate, we do everything other than the things that we know we should be doing. It is the biggest problem that almost everyone has with moving towards their goals so it deserves a whole chapter by itself. As you’ll see, there are a variety of approaches you can take to overcome procrastination. Once you’ve found the one that works best for you, you’ll have the edge over almost all your competitors.

First: are you sure you have a problem?

Before we start looking at the cures, let’s make sure you actually have the disease. If you put things off until what seems like the last minute, but then you get them done, and done well every time, you’re not procrastinating. You’re just choosing to spend your time on other things until it’s really time to work on a particular project, and then you do it. You’ve learned how to judge accurately how long something is going to take and you don’t like to start early. If the only thing bothering you is that someone else has characterised this as procrastination, ignore them and keep on doing what you’re doing, because it’s working.

“Better three hours too soon than one minute too late.”

The Merry Wives of Windsor

“I wasted time, and now doth time waste me.”

King Richard II

If, on the other hand, you miss deadlines or find that leaving things until the last minute causes you stress, you are a procrastinator and using the techniques in this chapter will help you.

The temptations of procrastination

To understand the dynamics of procrastination, let’s look at how temptation works. Generally you have a choice between two or more things. Sometimes it’s a simple “yes or no” choice: should you have this piece of chocolate cake or not? Sometimes it’s a choice between activities: will you stay in and watch TV or will you go to the gym to exercise? What determines your choice?

When Isaac Newton set out his laws of motion, he also unwittingly formulated some laws of human behaviour. Here’s how the first one is often stated:

An object at rest tends to stay at rest and an object in motion tends to stay in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force.

In human terms, a body at rest on a sofa tends to stay at rest. And a body in motion in a certain direction (for example, having a nice dinner) will tend to continue in that direction (eating a big piece of chocolate cake for dessert).

So, in order to change direction, we have to make some effort. But why is this so hard, since we are aware of the benefits of, for example, eating healthy food, exercising, or working on tasks in a measured way rather than putting them off until the last minute?

One reason is that the attractiveness of the “bad” option is very strong in the here and now. The attractiveness of the “good” option (or the punishment for ignoring it) tends to be weak in the here and now, and strong only in the long term. Here’s the key fact: generally, the “good” option pays off in the long run. The “bad” option pays off immediately. Therefore, the “bad” option is stronger in the moment.

For example, if I choose to spend the next couple of hours surfing the web, that’s fun right now. Maybe I really should be working on a report that’s due in two weeks, but if I don’t do that, there is no immediate punishment or drawback. The punishment arrives in a week, when I realise I’m now hopelessly behind, or in two weeks, when I miss the deadline and my client gets angry with me.

Here’s the other crucial difference: the short-term option often strongly engages our senses and emotions, whereas the long-term option – because it is not present right now – only engages our intellect.

In the battle between emotion and intellect, which do you think wins most of the time? Hint: take a look around at our world, at the wars, the spoiling of the environment, the personal debt level of the average person – the answer is all too clear.

The chocolate cake looks great, smells good, feels creamy on our tongue, and tastes wonderful! The idea of losing weight . . . er, well, it’s a nice idea . . . and at times, such as when we are overcome with guilt, it does have an impact. Unfortunately, this usually happens only after we overindulge.

Here is the key that will allow you to make the better choice every time: the secret of choosing the “good” option is to make it as vivid, emotional, and compelling in the moment as the “bad” option. How do you do this? By using your imagination to see, hear, taste, smell and feel the “good” choice even more strongly than the “bad” choice.

- Close your eyes and start to visualise the outcome of the “good” choice. This is important: don’t visualise yourself doing the task, visualise the end result or a step along the way.

- What will you see when you’ve done this? For example, what will you see when your business, for which you are just starting to write the business plan, is successful? If the business is a store, you can visualise the premises thronged with enthusiastic customers.

- What will you hear? Maybe you can imagine the customers complimenting you on the goods you are selling, or phoning their friends to tell them about your business.

- What will you feel? This may be the most important of all – perhaps you will feel proud, happy, excited, joyful.

- Sometimes smell comes into it as well. You might imagine yourself smelling the fresh flowers you have set up on the counter of your store.

- Even taste can be a factor. Maybe you imagine a dinner held to celebrate the opening of your business and someone toasts you and you drink a glass of champagne.

The more vivid and exciting you can make this, the more energy you will free up for getting started.

SUCCESSFUL VISUALISATION

If you have trouble getting into a visualisation of the result you want, start by remembering a similar time when you achieved something that gave you great satisfaction. Remember with all your senses what that was like, and then transfer these characteristics to the outcome of your current goal.

As with every exercise in this book, play around until you find the form that works best for you. For instance, some people might find it too scary to think ahead as far as the opening of their business; they might consider it more compelling to imagine just getting the loan they need in order to rent premises, or even just imagining the banker giving them compliments on their finished business plan.

When you’ve visualised whatever is most motivating for you, stay in that state of excitement after you open your eyes –suddenly, watching TV or surfing the internet will seem pretty boring by comparison. Launch into the task while the feeling is still fresh.

Add more focus with the power of an anchor

For the visualisation technique to work, you have to do it. For you to do it, you have to pause instead of just giving in to the path of least resistance. It’s a bit like remembering to count to 10 when you’re angry instead of immediately flying off the handle. So that you don’t have to take the time to do this every time you are tempted, it’s useful to “anchor” the desired state in a way that will make it easier for you to make the choice that is best for you. You’ve already read about this method and how it’s derived from the work of Pavlov and his dogs. Now let’s see how you can use it in situations where you want to avoid procrastinating:

- Choose a state that represents your positive feelings about the outcome of whatever you tend to procrastinate about. If you tend to put off exercising, use the state of fantastic healthful energy that comes from exercising. If you tend to put off working on a long-term project, use the state of the joy of having finished the project. If you tend to put off doing administrative tasks, use the state of relief and peace of mind that comes when they are out of the way.

- Stand up, close your eyes and, using your memory or your imagination, create as vivid a representation of that positive state as you can. Include what you see, hear, feel, and maybe taste and smell when you experience that state.

- Keep “turning up the volume” of these feelings until they feel really strong.

- When you attain a peak, make a gesture like squeezing together your thumb and forefinger. Hold it for a second, then release. This becomes your anchor, the signal that you will experience this state.

- Repeat the process a few times, ideally spread out over a day or two.

- To check how strong the association is, “drop the anchor” – that is, make the gesture and monitor your feelings. If the feeling isn’t strong yet, keep practising.

The next time you are tempted to procrastinate, make the appropriate gesture and you will find it easier to opt for the activity that will lead to your desired outcome.

Your reasons for resistance and how to overcome them

There may also be deeper reasons for your resistance to doing a particular task. If so, it will help you to identify those reasons or beliefs and challenge them. Here are the most common kinds of resistance and how to overcome them.

- Because the conditions aren’t right. Make a list of all the conditions you believe you need. Will these ever exist? If not, break your project down into small chunks and ask yourself whether the conditions are adequate for you to achieve the first small chunk. The answer probably will be yes, so do that chunk and then move on to the next one. If you still have trouble, make the chunks smaller and smaller.

- Because I work best in a crisis. If you’re a crisis junkie, consider giving yourself that adrenalin jolt some other way: bungee jumping, maybe? Seriously, try interspersing work sessions with a high-action computer game or hard exercise.

- Because I don’t want to and you can’t make me! Practise saying no to things you don’t want to do. If there’s any way to make the unwanted work go away, do it early on (by delegating, for example). If not, make an assessment of how doing the task will benefit you, and keep those benefits in mind.

- Because I insist on perfection. Give yourself permission to do it imperfectly. Practise doing some small things imperfectly and notice what happens (or what doesn’t happen). Work on toning down your harsh inner critic.

- Because it drives somebody else crazy, ha ha! If your procrastination is a way of rebelling against those who ask you do to things, consider whether there are more straightforward ways of expressing your anger or resentment or establishing a feeling of control. Often the best way to do this is not to take on the work in the first place, if possible.

- Because it doesn’t feel good. It doesn’t have to feel good, it just has to get done. But it’s easier if you combine it with something that does feel good (for example, listening to music while sorting through receipts for your tax statement) or reward yourself when the task is done.

What’s your reason?

Which of the above do you think is closest to your reasons for procrastinating?![]()

What will you do differently the next time you want to overcome your procrastination?![]()

If you’re still not sure . . .

There may be times when you’re not sure why you’re procrastinating, and getting more clarity about it could be what helps you to overcome this block. At those times it’s helpful to ask yourself some questions. The following sentence-completion technique is great for this because it brings to the surface things that may have been lodged in your subconscious mind. Once the facts are out, you can deal with them with one of the techniques we’ve already covered. If there’s something you’re procrastinating about at the moment, try doing the sentence-completion exercise now; if not, keep it handy for the next time procrastination is an issue.

Procrastination sentence completion

Write down the first thoughts that come to mind to complete each statement. The task I am procrastinating about is:![]()

- One thing that’s important to remember about this task is

- One person who could help me with this task is

- A similar task I’ve done successfully was

- One thing nobody knows about this task is

- A good symbol for this task is

- I’ll know this task has been accomplished successfully when

- A good song title for this problem/challenge would be

- One personal quality that could really help me with doing this task is

- If I had a magic wand to use to change one aspect of this task, I’d change

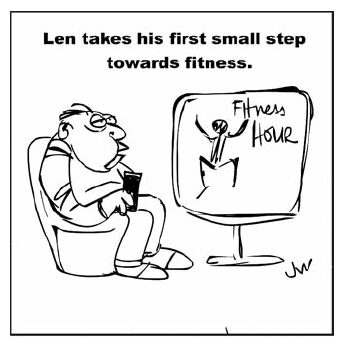

Taking the first step

The first step is often the hardest. Rather than tackle what seems to be a daunting task, it’s easier to put it off and do something else. In Chapter 4 you learned about the technique of chunking down a large task into small steps. The smaller the chunk, the easier it is to accomplish and the sooner you have the feeling that you’re on the way to reaching your goal.

The reason this works has been uncovered by the Procrastination Research Group run by Professor Timothy Pychyl at Ottawa’s Carleton University. His studies reveal that there seem to be two ways people function: some are action-oriented, and they switch easily from task to task; others are state-oriented, and they are more likely to procrastinate and suffer more from uncertainty, frustration, boredom and guilt. If you’re state-oriented, Pychyl suggests acknowledging that you don’t feel like doing the task, but promise yourself you’ll do it for 10 minutes. By the time you get to the end of that period, most likely your state will have shifted and you’ll be able to continue.

You can also extend the small chunks strategy by identifying a set of milestones that you will reach along the way to your goal. Research shows how powerful this can be: a 2001 study by Dan Ariely at the MIT Sloan School of Management and Klaus Wertenbroch at INSEAD gave one group a large task with only an end deadline, while another group had weekly deadlines leading towards the completion of the task. The group who had only one deadline were, on average, 12 days late. The ones who had weekly deadlines were, on average, only half a day late.

MAKE IT VISUAL

For larger projects you can draw a thermometer and label the intervals with the tasks you need to accomplish and your target dates. Colour in the segments of the thermometer as you complete each task. Keep the thermometer where you (and, ideally, others) can see it every day.

Procrastination and your “to-do” list

Handling the “to-do” list is probably the area in which the most people experience procrastination. As well as using the methods we’ve already covered, it might be helpful to identify your type. There are three basic ones:

- The Puritans: do the hardest things first, then enjoy doing the rest. These people eat their Brussels sprouts first.

- The Hedonists: do one or two easy things first, then gradually glide into doing the more difficult things. These people eat their pudding first.

- The Gamblers: write each task on an index card and, with eyes shut, shuffle them. Then do them in the order they come up (no reshuffling!). This panders to the gambler’s love of the unpredictable.

Which one is best? Whichever one works for you. Try them all, then follow the one that allows you to get the most important things done during the course of your day.

What’s next?

You now have an impressive set of strategies you can use to defeat procrastination and to focus on what will speed you towards success. In Part 3 you will discover a set of innovative focus tools that make this journey even easier and faster.

Website chapter bonus

At www.focusquick.com you will find a downloadable “kick start” brief guided visualisation to listen to when you need a boost to concentrate your energy on a task you’ve been avoiding.