11

Sample Business Plan for a Fictional Company

The sample business plan in this chapter shows the forecasts and cash flows for a company planning to produce three films. Due to space considerations, it is not practical to include separate business plans for both a single film and a company plan. They both follow the same format, but with some modifications. All of the costs for a one-film plan should be included in the budget, and summary tables are not necessary. Of course, the reader also has to modify the text that is shown in the book to relate to one film. For more information and detail on how to create the forecasts and cash flow, please refer to the “Financial Worksheet Instructions” on the companion website for this book.

Table 11.11 has the format for an overhead table. It is only meant to show some of the line items that you need to consider and has no data to match the Company Overhead numbers in Table 11.1. Not all companies will need all the line items, and some may have more. In addition, the place that the filmmaker lives and/or is filming will make a difference in the specifics for each expense. For example, rent in New York will not be the same as rent in Missoula or Berlin. One-film plans do not have an overhead table, as all your expenses are in the budget.

If you plan on accessing a state or country film incentive, include it after the section on Strategy but before Financial Assumptions. Tax incentives for films are not included in the sample business plan. Whether in the United States or other countries, incentives change on a regular basis. In some cases, they may be discontinued altogether or simply run out of funds to apply for after a period of time. Be sure to tell investors to check with their own tax advisors to see how a specific incentive would affect them. In addition, do not subtract potential incentives from your total budget. In the case of most U.S. state incentives and many of those in other countries, there is an accounting done by the governing body at the end of production before the actual dollars are awarded. The statement that you qualify for an incentive is not a guarantee on the amount of money you will receive.

Crazed Consultant Productions

The Business plan

CONTROLLED COPY

Issued to: __________

Issue Date: __________

Copy No.: __________

For Information Contact:

Louise Levison

Crazed Consultant Productions

c/o Business Strategies

4454 Ventura Canyon Ave. #305

Phone: 818-990-7774

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- / The Executive Summary 208

- / The Company 211

- / The Films 213

- / The Industry 216

- / The Markets 221

- / Distribution 225

- / Risk Factors 228

- / The Financial Plan 229

1 / The Executive Summary

Strategic Opportunity

- North American box office revenues in 2011 were $10.2 billion

- Revenues for independent films in 2011 were $3.4 billion, or 34 percent of the total North American box office

- Worldwide revenues from all sources for North American independent films were over $9 billion in 2011

- Worldwide box office revenues for 2011 were $32.6 billion

- The overall filmed entertainment market is projected to reach $45.1 billion in the United States in 2013 and $102.2 billion worldwide

The Company

Crazed Consultant Productions (CCP) is a startup enterprise engaged in the development and production of motion picture films for theatrical release. The first three films will be based on the Leonard the Wonder Cat books by Jane Lovable. CCP owns options on all three with two books already in print and a third currently being written. The books have sold 25 million copies in 12 countries. The movies based on Lovable’s series will star Leonard, a half-Siamese, half-American shorthair cat, whose adventures make for entertaining stories, and each of which includes a learning experience. The movies are designed to capture the interest of the entire family, building significantly on an already established base. CCP expects each film to stand on its own as a story.

The Company plans to produce three films over the next five years, with budgets ranging from $500,000 to $10.0 million. At the core of CCP are the founders, who bring to the Company successful entrepreneurial experience and in-depth expertise in motion picture production. The management team includes President and Executive Producer Ms. Lotta Mogul, Vice President/CFO Mr. Gimme Bucks, and Producer Ms. Ladder Climber.

The Films

Leonard’s Love: Natasha and her cat Leonard leave the big city to live in a small town, where they discover the true meaning of life.

Len’s Big Thrill: Leonard charms the director during Natasha’s audition for a movie and becomes a bigger star than Uggie the dog.

Cat Follies: His movie career gone, Leonard takes up professional ice skating. Discovered by a movie mogul, he is once again on top as a movie star.

The Industry

The future for low-budget independent films continues to look impressive, as their commercial viability has increased steadily over the past decade. Recent films, such as My Big Fat Siamese, Cat Surfers, and My Week with Phoebe, are evidence of the strength of this market segment. The independent market as a whole has expanded dramatically in the past 15 years, while the total domestic box office has increased 80 percent. At the 2005 through 2009 Academy Awards, four of the five films nominated for the Best Picture Oscar were independently financed. Technology has dramatically changed the way films are made, allowing independently financed films to look and sound as good as those made by the Hollywood studios, while remaining free of the creative restraints placed upon an industry that is notorious for fearing risks. Widely recognized as a “recession-proof” business, the entertainment industry has historically prospered even during periods of decreased discretionary income.

The Markets

Family films appeal to the widest possible market. Films such as the Tweetie Bird films, Me and My Doberman, and My Big Fat Siamese have proved that the whole family will go to a movie that they can see together. For preschoolers, there are adorable animals, while tweens and teens get real-life situations and expertly choreographed action, and parents enjoy the insider humor. The independent market continues to prosper. As an independent company catering to the family market, CCP can distinguish itself by following a strategy of making films for this well-established and growing genre.

Distribution

The motion picture industry is highly competitive, with much of a film’s success depending on the skill of its distribution strategy. As an independent producer, CCP aims to negotiate with major distributors for release of their films. The production team is committed to making the films attractive products in theatrical and other markets.

Investment Opportunity and Financial Highlights

CCP is seeking an equity investment of approximately $13.5 million for development and production of three films and an additional $1.0 million for overhead expenditures. Using a moderate revenue projection and an assumption of general industry distribution costs, we project (but do not guarantee) gross worldwide revenues of $109.4 million, with pretax producer/investor net profit of $22.3 million.

2 / The Company

CCP is a privately owned California corporation that was established in September 2011. Our principal purpose and business are to create theatrical motion pictures. The Company plans to develop and produce quality family-themed films portraying positive images of the household cat.

The public is ready for films with feline themes. Big-budget animal-themed films have opened in the market over the past five years. In addition, the changing balance of cat to dog owners in favor of the former is an allegory for changes in society overall. The objectives of CCP are as follows:

- To produce quality films that provide positive family entertainment with moral tales designed for both enjoyment and education.

- To make films that will celebrate the importance of the household cat and that will be exploitable to a mass audience.

- To produce three feature films in the first five years, with budgets ranging from $500,000 to $10 million.

- To develop scripts with outside writers.

There is a need and a hunger for more family films. We believe that we can make exciting films starting as low as $500,000 without sacrificing quality. Until recently, there was a dearth of cat films. We plan to change the emphasis of movies from penguins, pigs, and dogs to cats, while providing meaningful and wholesome entertainment that will attract the entire family. In view of the growth of the family market in the past few years, the cat theme is one that has been undervalued and, consequently, underexploited.

Production Team

The primary strength of any company is in its management team. CCP’s principals Lotta Mogul and Gimme Bucks have extensive experience in business and in the entertainment industry. In addition, the Company has relationships with key consultants and advisers who will be available to fill important roles on an as-needed basis. The following individuals make up the current management team and key managers.

Lotta Mogul, Executive Producer

As Executive Producer, Lotta Mogul will oversee the strategic planning and financial affairs of the Company. She previously ran Jeffcarl Studios, where she oversaw the production and distribution of over 15 films. Among her many credits are Lord of the Litter Box, The Dog Who Came for Dinner, Fluffy Goes to College, and the Feline Avengers franchise, which earned more than $600 million. Before moving into film, Mogul was Vice President of Marketing at Lendaq, an American multinational corporation that provides Internet-related products and services.

Gimme Bucks, Producer

With 10 years experience in the entertainment industry, Gimme Bucks most recently produced the comic-action-thriller Swarm of Locusts for Forthright Entertainment. He made his directorial debut on Cosmic Forces, which Wondergate is releasing in 2013. Bucks also has been a consultant to small, independent film companies.

Better Focus, Cinematographer

Better Focus is a member of the American Society of Cinematographers. He was Alpha Numerical’s director of photography for several years. He won an Emmy Award for his work on Unusual Birds of Ottumwa, and he has been nominated twice for Academy Awards.

Ladder Climber, Co-Producer

Ladder Climber will assist in the production of our films. She began her career as an assistant to the producer of the cult film Dogs That Bark and has worked her way up to production manager and line producer on several films. Most recently, she served as a line producer on The Paw and Thirty Miles to Azusa.

Consultants

Samuel Torts, Attorney-at-Law, Los Angeles, CA

Winners and Losers, Certified Public Accountants, Los Angeles, CA

3 / The Films

Currently, CCP controls the rights to the first three Leonard the Wonder Cat books by Jane Lovable. The books will be the basis for its film projects over the next five years. In March 2011, the Company paid $10,000 for three-year options on the first three books and first refusal on the next three. The author will receive additional payments over the next four years as production begins. The Leonard series has been obtained at very inexpensive option prices due to the author’s respect for Lotta Mogul’s devotion to charitable cat causes. Three film projects are scheduled.

Leonard’s Love

The first film will be based on the novel Leonard’s Love, which has sold 10 million copies. The story revolves around the friendship between a girl, Natasha, and her cat, Leonard. The two leave the big city to live in a small town, where they discover the true meaning of life. Furry Catman has written the screenplay. The projected budget for Leonard’s Love is $500,000, with CCP producing and Ultra Virtuoso directing. Virtuoso’s previous credits include a low-budget feature, My Life as a Ferret, and two rock videos, Feral Love and Hot Fluffy Rag. We are currently in the development stage with this project. The initial script has been written, but we have no commitments from actors. Casting will commence once financing is in place. As a marketing plus, the upcoming movie will be advertised on the cover of the new paperback edition of the book.

Len’s Big Thrill

Natasha is an actress in her late thirties still trying to get her big break in Hollywood. She lives in a small one bedroom in Marina del Rey. On a good day, she can see the ocean if she stands on the furthest corner of her narrow balcony. Her closest companion is her cat, Leonard. He has been through many auditions with Natasha, quietly sitting on the sidelines while she tries for that big break. To make matters worse, Natasha has just gotten a final notice to pay her rent or be evicted.

One day in September, Len accompanies Natasha while she auditions for yet another movie role. Getting the lead in this movie would solve her current financial problems. Restless with the wait at the audition, Leonard struts across the room. Seeing the cameraman, he looks directly into the camera and appears to smile. The director, Simon Sez, is captivated by Len’s natural ease in front of a camera. He thinks the cat actually is posing. Then he gives the cat some stage directions—run across the room, jump on the chair, and pretend to sleep—that Leonard appears to follow. The cameraman, Wayne, doesn’t believe it. He points out to Simon that household cats are hard to train and seldom follow verbal directions from a stranger.

When Natasha reads for her role, Simon is equally captivated by her. He wants to make a deal for both Natasha and Leonard to be in the film, but she is hesitant. Simon explains that he wants to rewrite the script to feature Leonard as the cat who saves his mistress from a burning building. After years of waiting for her big break, Natasha feels that he wants to hire her only to get Leonard into the film. In addition, she thinks that Simon may be one of those directors who are more interested in a one-night stand with actresses. Natasha declines the part for both of them and leaves the studio with her cat.

Simon refuses to give up. He sends flowers and calls every day. When serious attempts don’t work, he tries humor. One day a fellow dressed as a Siamese cat shows up at the door with a singing telegram. The song, written by Simon, is from another cat begging her to let him play with Leonard on the set. On another day, UPS delivers a box of movie posters showing both Natasha and Leonard posing in front of a burning building. The posters are accompanied by fake online reviews about the “new” actress, Natasha, who is sure to win an Academy Award for Best Actress. Then, he has former girlfriends call her to extol his virtues and guarantee that he is one of the good guys. Finally, he calls and invites her for coffee to discuss the project.

The coffee business meeting turns into lunch that turns into dinner. Natasha realizes that she is attracted to this man; however, she worries that having a relationship with him may just be her own desire for the movie part and the paycheck. Simon assures her that his intentions are honorable. He suggests that they put any personal relationship on the back burner, so that she will feel comfortable. He says that she was the best actress to test for the part. Leonard’s antics would add that much more to the film. He is willing to go with the original script, if Natasha wants. After thinking about it for a week, Natasha decides to go ahead with the film including the cat’s part.

Despite Wayne’s misgivings, Len is a natural in front of the camera. Although they hire a trainer for him, he prefers to follow Natasha’s requests. As a true Siamese, he doesn’t like commands. The film is a smash with audiences. Walking the red carpet turns out to be one of Len’s favorite activities. Finally realizing they are in love, Natasha and Simon marry, giving Len the biggest thrill of all.

Cat Follies

The third book in the series is currently being written by Lovable and will be published in late 2013. The story features a dejected Leonard, whose films aren’t drawing the audiences they used to. No matter what Natasha and Simon, his human parents, do, they can’t cheer up our cat. Desperate to find something to encourage Len, they take him for ice skating lessons. Amazed at Leonard’s agility on skates, his teacher contacts the Wonderland Follies, who sign Leonard to a contract. He is an immediate hit with the audience, especially the young people. As luck would have it, one night film mogul Harvey Hoffenbrauer is in the audience. Seeing the reaction of both kids and adults to Leonard, he decides to make a film of the follies. Soon Leonard is back on top.

4 / The Industry

The future for independent films continues to look impressive, as their commercial viability has increased steadily over the last decade. Recent films, such as My Big Fat Siamese, Cat Surfers, and My Week with Phoebe are evidence of the strength of this market segment. In addition, every year since 2006, an independent film has won the Academy Award for Best Picture: Crash (2006), The Departed (2007), No Country for Old Men (2008), Slumdog Millionaire (2009), The Hurt Locker (2010), The King’s Speech (2011), and The Artist (2012). As studios cut back, equity investors have been moving into the independent film arena. Lately, falling salaries, rising subsidies, and a thinning of competition have weighted the financial equation even more in favor of the investor. In addition, revolutionary changes in the manner in which motion pictures are produced and distributed are now sweeping the industry, especially for independent films.

The total North American box office in 2011 was $10.2 billion. The share for independent films was $3.4 billion, or 34 percent of the 2011 total. Revenues for North American independent films from all worldwide revenue sources for 2011 are estimated at more than $9 billion. Worldwide box office revenues totaled $32.6 billion in 2011. Projections for 2013 are for the overall filmed entertainment market to reach $45.1 billion in the United States and $102.2 billion worldwide. Once dominated by the studio system, movie production has shifted to reflect the increasingly viable economic models for independent film. The success of independent films has been helped by the number of new production companies and smaller distributors emerging into the marketplace every day, as well as the growing interest of major U.S. studios in providing distribution in this market. Also, there has been a rise in the number of screens available for independent films.

Investment in film becomes an even more attractive prospect as financial uncertainty mounts in the wake of Wall Street bailouts and international stock market slides. Widely recognized as a “recession-proof" business, the entertainment industry has historically prospered even during periods of decreased discretionary income. While the North American box office was down 4 percent in 2011, it is up 14 percent year-to-date. “In mature markets such as the United States, the business can be more cyclical in the short term, driven by product supply and distribution patterns,” National Association of Theatre Owners President John Fithian stated. “In the long term, however, domestic revenues continue to grow … 2012 looks to be another growth year.” Senator Thomas Dodd, Chairman and CEO of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), declared at the December 2011 Asia Pacific Screen Awards, “I am proud to report that the film industry remains a key driver of economic growth around the globe.”

Motion Picture Production

The structure of the U.S. motion picture business has been changing over the past few years at a faster pace, as studios and independent companies have created varied methods of financing. Although studios historically funded production totally out of their own arrangements with banks, they now look to partner with other companies, both in the United States and abroad, which can assist in the overall financing of projects. The deals often take the form of the studio retaining the rights for distribution in all U.S. media, including theatrical, home video, television, cable, and other ancillary markets.

The studios, the largest companies in this business, are generally called the “Majors” and include NBC Universal (owned by Comcast Corp.), Warner Bros. (owned by Time Warner), Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation (owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp.), Paramount Pictures (owned by Viacom), Sony Pictures Entertainment, and The Walt Disney Company. MGM, one of the original Majors, has been taken private by investors and is being run as an independent company by Spyglass Entertainment Co-Chairmen Roger Birnbaum and Gary Barber. In most cases, the Majors own their own production facilities and have a worldwide distribution organization. With a large corporate hierarchy making production decisions and a large amount of corporate debt to service, the studios aim most of their films at mass audiences.

Producers who can finance independent films by any source other than a major U.S. studio have more flexibility in their creative decisions, with the ability to hire production personnel and secure other elements required for pre-production, principal photography, and post-production on a project-by-project basis. With substantially less overhead than the studios, independents are able to be more cost-effective in the filmmaking process. Their films can be directed at both mass and niche audience, with the target markets for each film dictating the size of its budget. Typically, an independent producer’s goal is to acquire funds from equity partners, completing all financing of a film before commencement of principal photography.

How It Works

There are four typical steps in the production of a motion picture: development, pre-production, production, and post-production. During development and pre-production, a writer may be engaged to write a screenplay or a screenplay may be acquired and rewritten. Certain creative personnel, including a director and various technical personnel, are hired; shooting schedules and locations are planned; and other steps necessary to prepare the motion picture for principal photography are completed. Production commences when principal photography begins and generally continues for a period of not more than three months. In post-production, the film is edited, which involves transferring the original filmed material to digital media in order to work easily with the images. In addition, a score is mixed with dialogue, and sound effects are synchronized into the final picture, and, in some cases, special effects are added. The expenses associated with this four-step process for creating and finishing a film are referred to as its “negative costs.” A master is then manufactured for duplication of release prints for theatrical distribution and exhibition, but expenses for further prints and advertising for the film are categorized as “P&A” and are not part of the negative costs of the production.

Theatrical Exhibition

There were 42,390 theater screens (including drive-ins) in the United States out of approximately 150,000 theater screens worldwide in 2011, per the most recent report of the MPAA. Film revenues from all other sources are often driven by the U.S. domestic theatrical performance. The costs incurred with the distribution of a motion picture can vary significantly depending on the number of screens on which the film is exhibited. Although studios often open a film on 3,000 to 4,000 screens on opening weekends (depending on the budget of both the film and the marketing campaign), independent distributors usually tend to open their films on fewer screens. Theatrical revenues, or “box office,” are often considered an engine to drive sales in all other categories. Not only has entertainment product been recession-resistant domestically but also the much stronger than expected domestic theatrical box office has continued to stimulate ancillary sales, such as home video and digital, as well as raising the value of films in foreign markets.

Television

Television exhibition includes over-the-air reception for viewers through either a fee system (cable) or a “free television” (national and independent broadcast stations). The proliferation of new cable networks since the early 1990s has made cable (both basic and premium stations) one of the most important outlets for feature films. Although network and independent television stations were a substantial part of the revenue picture in the 1970s and early 1980s, cable has become a far more important ancillary outlet. The pay-per-view business has continued to grow thanks to continued direct broadcast satellite (DBS) growth. Pay-per-view and pay television allow cable television subscribers to purchase individual films or special events or subscribe to premium cable channels for a fee. Both acquire their film programming by purchasing the distribution rights from motion picture distributors.

Home Video

In 2011, overall consumer spending on home video totalled $18.0 billion, according to the Digital Entertainment Group, consisting of $14.6 billion from DVD/Blu-ray sales and rentals and $3.4 billion from digital download (including electronic sell-through, video on demand [VOD], and subscription streaming). Annual spending on Blu-ray discs jumped 20 percent, hitting $2 billion for the first time. At the same time, total penetration of Blu-ray disc playback devices—including set-top box and game consoles—reached 40 million households in 2011, an increase of 38 percent. Consumers also purchased more than 27 million HDTVs during 2011, raising HDTV penetration to 74.5 million households.

The VOD market for paid rentals is currently ruled by pay TV services, but the Internet-on-demand (iVOD) market is growing in strength, according to the NPD Group. Pay TV VOD services hit $1.3 billion in revenue for 2011, according to NPD, while the iVOD market reached $204 million. Including the services of iTunes, Amazon, Vudu, and others, iVOD reached 7 million users, compared to 40 million for pay TV VOD. Internet VOD also poses a possible challenge for pay TV’s nonmovie services. “IVOD users reduced their time spent watching TV shows, news and sports via pay TV companies by 12 percent between August 2010 and August 2011,” said Russ Crupnick, Senior Vice President of Industry Analysis for the NPD Group. “Pay TV operators now must not only defend their movie VOD revenues but also counter an emerging threat to basic programming.” Note that all findings are based on NPD’s VideoWatch tracking service, which does not consider free or paid viewings of TV shows, subscription services, such as Netflix streaming, or free movies included in pay TV subscriptions.

International Theatrical Exhibition

Much of the projected growth in the worldwide film business comes from foreign markets, as distributors and exhibitors keep finding new ways to increase the box office revenue pool. More screens in Asia, Latin America, and Africa have followed the increase in multiplexes in Europe, but this growth has slowed. The world screen count is predicted to remain stable over the next nine years. Other factors include the privatization of television stations overseas, the introduction of DBS services, and increased cable penetration. The synergy between international and local product in European and Asian markets is expected to lead to future growth in screens and box office.

Future Trends

Revolutionary changes in the manner in which motion pictures are produced and distributed are now sweeping the industry, especially for independent films. Web-based companies like Movielink (owned by Blockbuster), Amazon’s Video on Demand, CinemaNow, and Apple’s iTunes Store are selling films and other entertainment programming for download on the Internet, and websites such as Netflix and Hulu (through Hulu Plus) stream filmed entertainment to home viewers as rentals. New devices for personal viewing of films (including Xbox, Wii, video iPod, iPhone, and iPad) are gaining ground in the marketplace, expanding the potential revenues from home video and other forms of selling programming for viewing. Although there may not be a notable impact of the new technologies at present, their influence is expected to grow significantly over the next five years.

5 / The Market

The independent market continues to prosper. The strategy of making films in well-established genres has been shown time and time again to be an effective one. Although there is no boilerplate for making a successful film, the film’s probability of success is increased with a strong story, and then the right elements—the right director and cast and other creative people involved. Being able to greenlight our own product, with the support of investors, allows the filmmakers to attract the appropriate talent to make the film a success and distinguish it in the marketplace.

CCP feels that its first film will create a new type of moviegoer for these theaters and a new type of commercial film for the mainstream theaters. Although we expect Leonard’s Love to have enough universal appeal to play in the mainstream houses, at its projected budget it may begin in the specialty theaters as the blockbuster Sylvester Barks at Midnight did. Because of the low budget, exhibitors may wait for our first film to prove itself before providing access to screens in the larger movie houses. In addition, smaller houses will give us a chance to expand the film on a slow basis and build awareness with the public.

Target Markets

Family-Friendly Films

Family-friendly films appeal to the widest possible market, with Leonard’s Love and its sequels having a multigenerational audience from tweens to grandparents. Variety and industry websites have said that family films boost the box office. John Fithian, President of the National Association of Theater Owners, said, “Year after year, the box office tells an important story for our friends in the creative community. Family-friendly films sell.” Previously thought of only as kids’ films, family-friendly movies now offer a new paradigm of family entertainment. Production and distribution companies know that wholesome entertainment can be profitable. “Movies that have a good message for [young people] that adults enjoy are universally embraced,” says Tom Rothman of Twentieth Century Fox.

Cat Owners

The two most popular pets in most Western countries have been cats and dogs, with cats outnumbering dogs in 2011, according to a study by the American Pet Products Manufacturers. In the United States, there are 86.4 million pet cats compared to 78.2 million pet dogs. The statistics reveal that 39 percent (44.3 million) of households own at least one pet dog compared to 33 percent (38.4 million) that own cats. This seeming contradiction is due to the fact that the average household with a cat owns at least two. Overall, pet ownership is currently at its highest level since the first study, with 115.5 households owning a pet in 2011 compared to 71.1 million households in 1988.

The time has finally come for the cat genre film. Felines have been with us for 12 million years, but they have been underappreciated and underexploited, especially by Hollywood. Recent studies have shown that the cat has become the pet of choice. We plan to present domestic cats in their true light, as regular, everyday heroes with all the lightness and gaiety of other current animal cinema favorites, including dogs, horses, pigs, and bears. As the pet that is owned by more individuals than any other animal in the United States, a cat starring in a film will draw audience from far and wide. In following the tradition of the dog film genre, we are also looking down the road to cable outlets. There is even talk of a cat television channel.

CCP plans to begin with a $500,000 film that would benefit from exposure through the film festival circuit. The exposure of our films at festivals and limited runs in specialty theaters in target areas will create awareness for them with the general public. In addition, we plan to tie-in sales of the Leonard books with the films. Although a major studio would be a natural place to go with these films, we want to remain independent.

Demographics

Moviegoers of All Ages

The Leonard films are designed to appeal to everyone from children to their grandparents. It plays to younger ages better than many animated films, while still bringing in the whole family demographic. The MPAA counts all moviegoers from ages 12 to 90 in specific groups in their annual “Theatrical Market Statistics” analysis. Young adolescents, teenagers, and young adults comprised 46 percent of the movie audience in 2011, according to the most recent MPAA report. Those over 40 comprised another 39 percent.

The moviegoers dubbed “tweens” (ages 8-12) has emerged as a force at the box office during the past several years. According to recent market research figures, this group numbers about 30 million and accounts for more than $50 billion in spending. Since the MPAA’s audience data groups ages 2 to 11 together, we can’t present a separate audience percentage for children and tweens. According to the numbers, youngsters would be 15 percent of the audience.

Social Media and Self-Marketing

An important marketing component for any film, especially during its opening weekend, is word of mouth. Without incurring additional costs, it is possible for the filmmakers and their many colleagues to supplement the marketing strategy of a distribution company by working through niche channels to spread word of mouth about the film. Typically, film companies use the Internet to great effect with “viral” marketing. It is a strategy that encourages individuals to pass on an email or video marketing message to others, creating the potential for exponential growth in the message’s exposure and influence. The recipients of those emails then forward them to their friends. As with any mainstream marketing, the strategy starts with the people at the top, the opinion makers or “influencers,” and their channel partners, and it extends through the ranks to the people who see films the first weekend. They then spread the word to everyone else.

Complementing this approach are the more purely social networks. It is a $1.0-billion industry projected to grow to $2.4 billion by the end of 2012. Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and other social networking sites have more than doubled since 2007, according to Forrester Research. Facebook (one billion users in August 2012, according to The Associated Press) and Twitter (140 million users in March 2012, according to the company itself) in particular have clearly become one of the focus sectors in media and entertainment. With their large communities, finding “friends” of similar film tastes in a social network is fairly easy. Twitter has become a force in the success of many films. Fans blog reviews on their own web pages or even make a video recording of their reactions and post these to YouTube, their own sites, or a social networking page and then “tweet” the link to their followers, thus informing friends and Web surfers about a film and influencing their opinions. In addition, some celebrities gather huge followings on Twitter, using the website to address their fans directly and plug their projects not only at time of release but also throughout filming to create anticipation.

There are also websites that are Web-based marketplaces where filmmakers and fans connect to make independent films happen through small individual contributions to funding and other forms of support. Fans get the opportunity to discover and impact the films of tomorrow, while getting insider access and VIP perks for their contributions.

6 / Distribution

The motion picture industry is highly competitive, with much of a film’s success often depending on the skill of its distribution strategy. The filmmakers’ goal is to negotiate with experienced distribution companies in order to seek to maximize their bargaining strength for potentially significant releases. There is an active market for completed motion pictures, with virtually all the studios and independent distributors seeking to acquire films. The management team feels that the Company’s films will be attractive products in the marketplace.

Distribution terms between producers and distributors vary greatly. A distributor looks at several factors when evaluating a potential acquisition, such as the uniqueness of the story, theme, and the target market for the film. Since distribution terms are determined in part by the perceived potential of a motion picture and the relative bargaining strength of the parties, it is not possible to predict with certainty the nature of distribution arrangements. However, there are certain standard arrangements that form the basis for most distribution agreements. The distributor will generally license the film to theatrical exhibitors (i.e., theater owners) for domestic release and to specific, if not all, foreign territories for a percentage of the gross box office dollars. The initial release for most feature films is U.S. theatrical (i.e., in movie theaters). For a picture in initial release, the exhibitor, depending on the demand for the movie, will split the revenue derived from ticket purchases (“gross box office”) with the distributor; revenue derived from the various theater concessions remains with the exhibitor. The percentage of box office receipts remitted to the distributor is known as “film rentals” and customarily diminishes during the course of a picture’s theatrical run. Although different formulas may be used to determine the splits from week to week, on average a distributor will be able to retain about 50 percent of total box office, again depending on the performance and demand for a particular movie. In turn, the distributor will pay to the motion picture producer a negotiated percentage of the film rentals less its costs for film prints and advertising.

Film rentals become part of the “distributor’s gross,” from which all other deals are computed. As the distributor often re-licenses the picture to domestic ancillaries (i.e., cable, television, home video) and foreign theatrical and ancillaries, these monies all become part of the distributor’s gross and add to the total revenue for the film in the same way as the rentals. The distribution deal with the producer includes a negotiated percentage for each revenue source; for example, the producer’s share of foreign rentals may vary from the percentage of domestic theatrical rentals. The basic elements of a film distribution deal include the distributor’s commitment to advance funds for distribution expenses (including multiple prints of the film and advertising) and the percentage of the film’s income the distributor will receive for its services. Theoretically, the distributor recoups his expenses for the cost of its print and advertising expenses first from the initial revenue of the film. Then the distributor will split the rest of the revenue monies with the producer/investor group. The first monies coming back to the producer/investor group generally repay the investor for the total production cost, after which the producers and investors split the money according to their agreement. However, the specifics of the distribution deal and the timing of all money disbursements depend on the agreement that is finally negotiated. In addition, the timing of the revenue and the percentage amount of the distributor’s fees differ depending on the revenue source.

Release Strategies

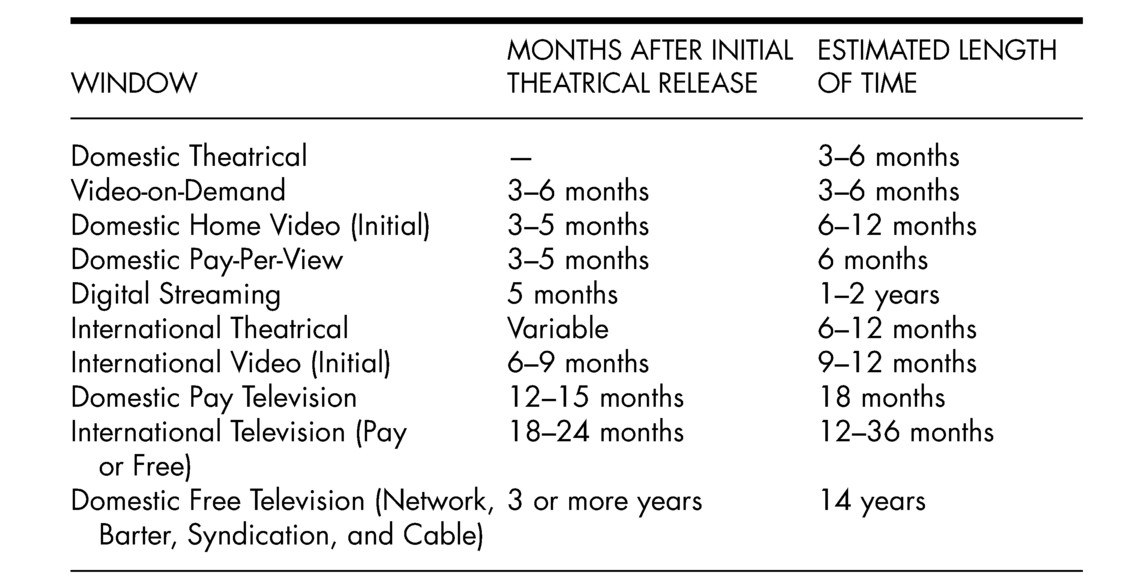

The typical method of releasing films is with domestic theatrical, which gives value to the various film “windows” (the period that has to pass after a domestic theatrical release before a film can be released in other markets). Historically, the sequencing pattern has been to license to pay-cable program distributors, foreign theatrical, home video, television networks, foreign ancillary, and U.S. television syndication. As the rate of return varies from different windows, shifts in these sequencing strategies will occur.

The business is going through a changeover between screens that play 35-mm films and those that accept digital, which makes a difference in the cost of what we usually call “prints.” Traditional 35-mm prints typically cost $1,200 to $1,500 each. Using film prints, a high-profile studio film opening on as many as 3,000 to 4,000 screens in multiple markets (a “wide” release) can have an initial marketing expense of $3.5 to $6 million, accompanied by a very high-priced advertising program. The number of screens diminishes after opening weekend as the film’s popularity fades.

By contrast, independent films typically have a “platform” release. In this case, the film is given a build up by opening initially in a few regional or limited local theaters to build positive movie patron awareness throughout the country. The time between a limited opening and its release in the balance of the country may be several weeks. This keeps the cost of striking 35-mm prints to a minimum, in the range of over $1 million, and allows for commensurately lower advertising costs. Using this strategy, smaller budgeted films can be successful at the box office with as few as two or three prints initially and more being made as the demand increases. In the new digital system, the distributor pays $800 to $900 fee per theatrical screen on which the film is exhibited. For independent films that are in theaters for at least two months on an escalating number of screens, adhering to the platform release pattern, the overall distribution cost can still run between $1 and $2 million.

Distributors plan their release schedules not only with certain target audiences in mind but also with awareness of which theaters—specialty or multiplex—will draw that audience. Many specialty theaters remain print oriented, while multiplexes are rapidly converting to all digital. How much is spent by the distributor in total will depend on which system, and which release pattern, best serves each film.

7 / Risk Factors

Investment in the film industry is highly speculative and inherently risky. There can be no assurance of the economic success of any motion picture since the revenues derived from the production and distribution of a motion picture primarily depend on its acceptance by the public, which cannot be predicted. The commercial success of a motion picture also depends on the quality and acceptance of other competing films released into the marketplace at or near the same time, general economic factors, and other tangible and intangible factors, all of which can change and cannot be predicted with certainty.

The entertainment industry in general, and the motion picture industry in particular, are continuing to undergo significant changes, primarily due to technological developments. Although these developments have resulted in the availability of alternative and competing forms of leisure time entertainment, such technological developments have also resulted in the creation of additional revenue sources through licensing of rights to such new media and potentially could lead to future reductions in the costs of producing and distributing motion pictures. In addition, the theatrical success of a motion picture remains a crucial factor in generating revenues in other media such as videocassettes and television. Due to the rapid growth of technology, shifting consumer tastes, and the popularity and availability of other forms of entertainment, it is impossible to predict the overall effect these factors will have on the potential revenue from and profitability of feature-length motion pictures.

The Company itself is in the organizational stage and is subject to all the risks incident to the creation and development of a new business, including the absence of a history of operations and minimal net worth. In order to prosper, the success of the Company’s films will depend partly upon the ability of management to produce a film of exceptional quality at a lower cost that can compete in appeal with high-budgeted films of the same genre. In order to minimize this risk, management plans to participate as much as possible throughout the process and will aim to mitigate financial risks where possible. Fulfilling this goal depends on the timing of investor financing, the ability to obtain distribution contracts with satisfactory terms, and the continued participation of the current management.

8 / Financial Plan

Strategy

The Company proposes to secure development and production film financing for the feature films in this business plan from equity investors, allowing it to maintain consistent control of the quality and production costs. As an independent, CCP can strike the best financial arrangements with various channels of distribution. This strategy allows for maximum flexibility in a rapidly changing marketplace, in which the availability of filmed entertainment is in constant flux.

Financial Assumptions

For the purposes of this business plan, several assumptions have been included in the financial scenarios and are noted accordingly. This discussion contains forward-looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties as detailed in the Risk Factors section.

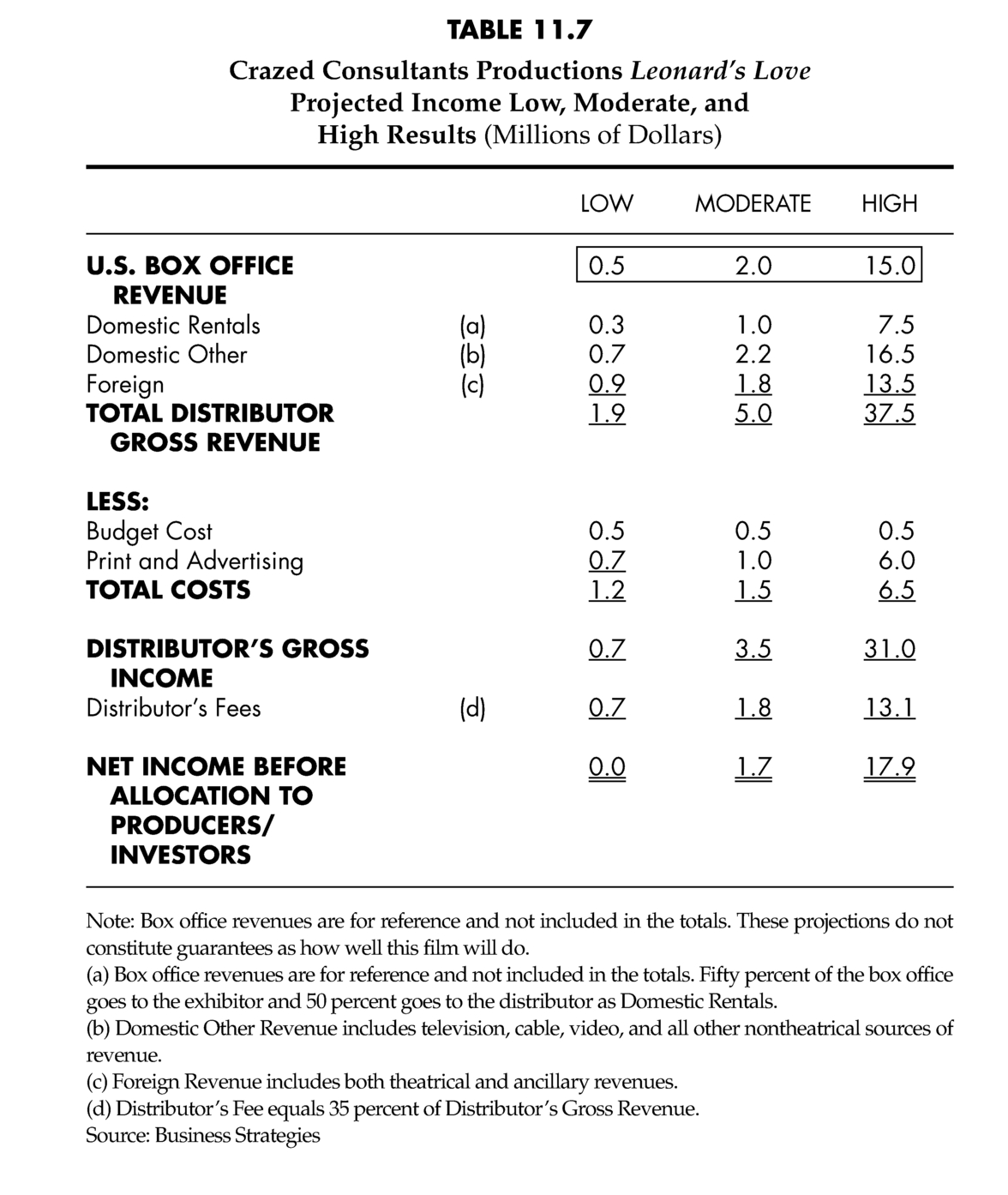

- Table 11.1, Summary Projected Income Statement, summarizes the income for the films to be produced. Domestic Rentals reflect the distributor’s share of the box office split with the exhibitor in the United States and Canada, assuming the film has the same distributor in both countries. Domestic Other includes home video, pay TV, basic cable, network television, and television syndication. Foreign Revenue includes all monies returned to distributors from all venues outside the United States and Canada.

- The film’s Budget, often known as the “production costs,” covers both “above-the-line” (producers, actors, and directors) and “below-the-line” (the rest of the crew) costs of producing a film. Marketing costs are included under Print and Advertising (P&A), often referred to as “releasing costs” or “distribution expenses.” These expenses also include the costs of making copies of the release print from the master and advertising and vary depending on the distribution plan for each title.

- Gross Income represents the projected pretax profit after distributor’s expenses have been deducted but before distributor’s fees and overhead expenses are deducted.

- Distributor’s Fees (the distributor’s share of the revenues as compared to his expenses, which represent out-of-pocket costs) are based on 35 percent of all distributor gross revenue, both domestic and foreign.

- Net Producer/Investor Income represents the projected pretax profit prior to negotiated distributions to investors.

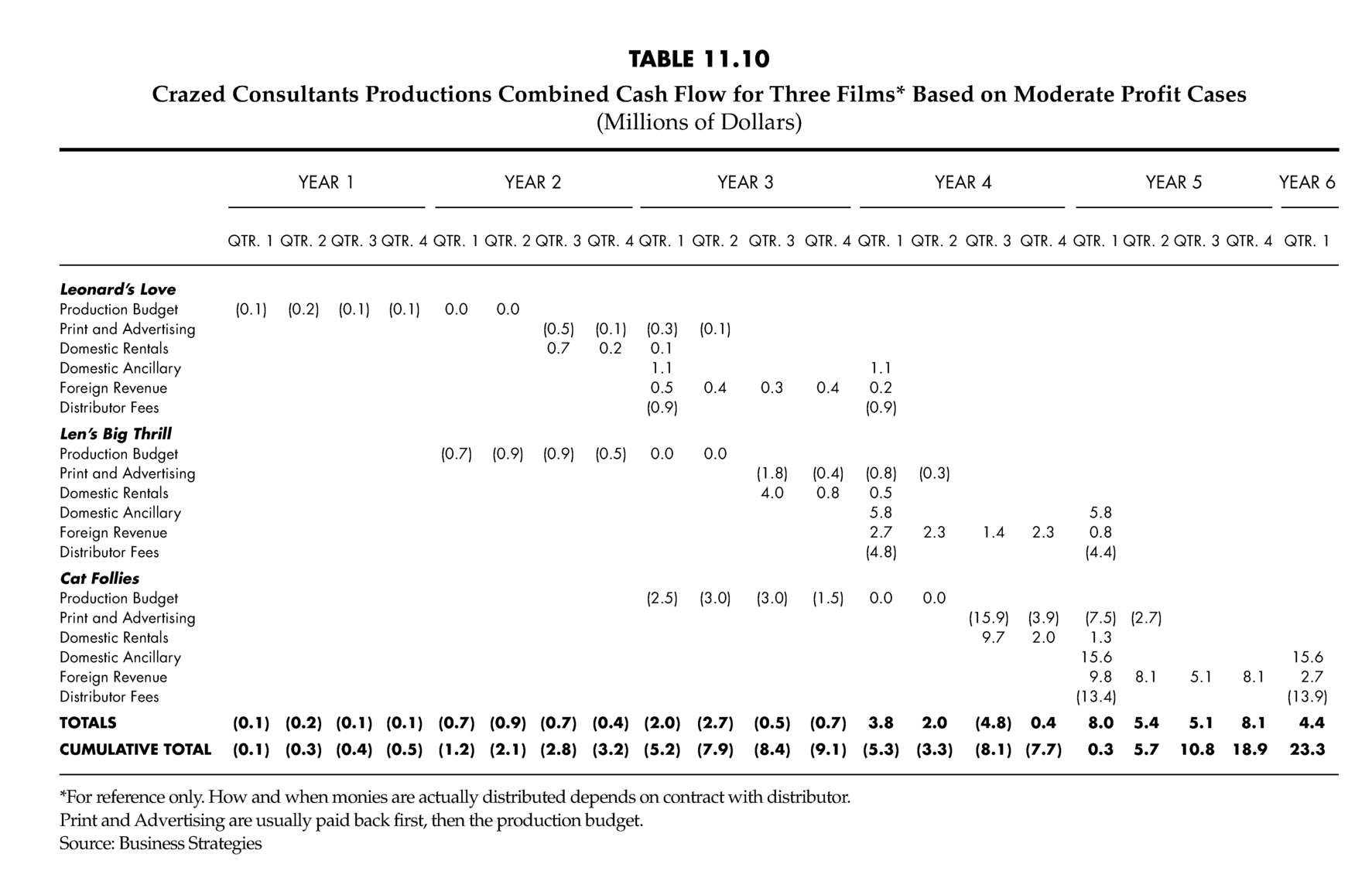

- Table 11.2 shows the Summary Projected Cash Flow Based on Moderate Profit Cases, which have been brought forward from Table 11.10.

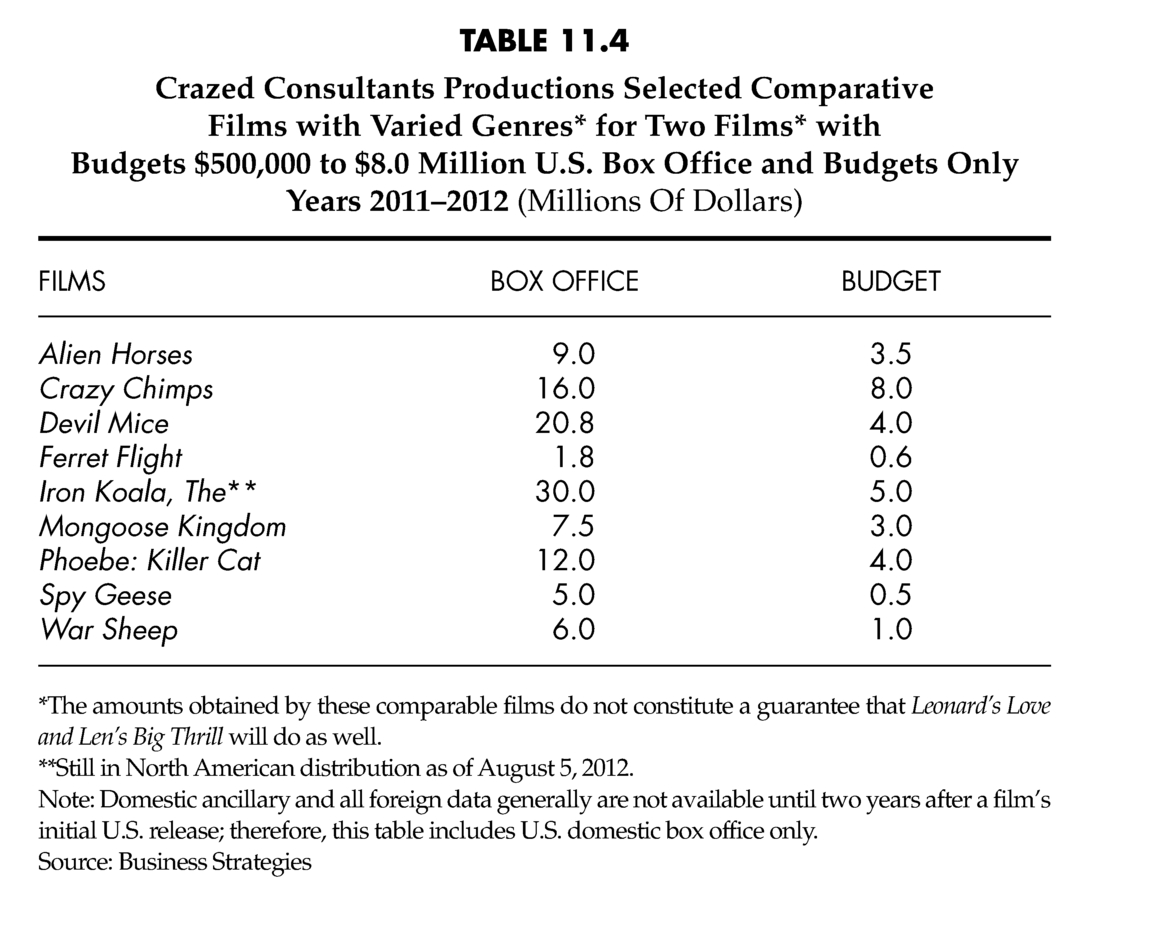

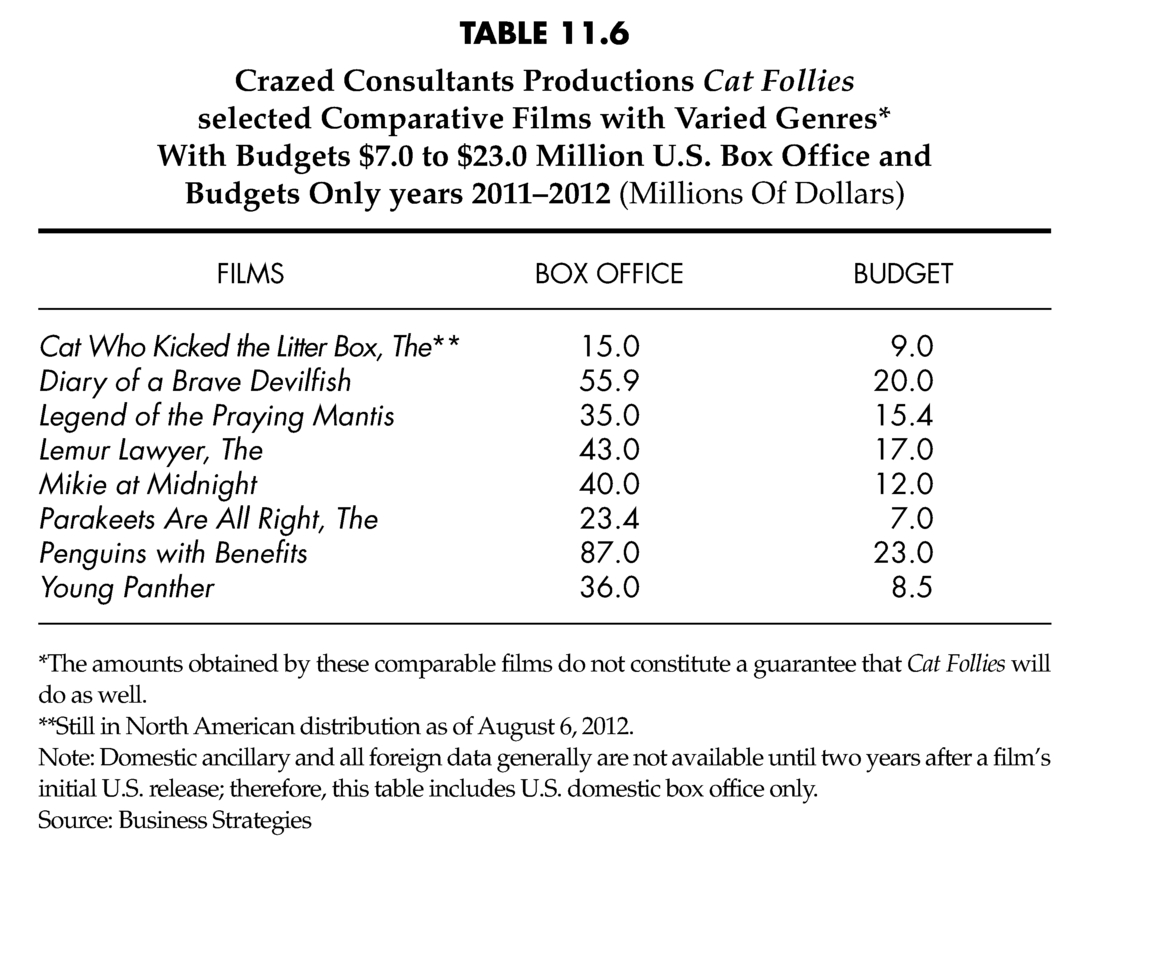

- The films in Tables 11.3 and 11.4 are the basis for the projections shown in Tables 11.7 and 11.8. Likewise, the films in Tables 11.5 and 11.6 are the basis for the projections in Table 11.9. The rationale for the projections is explained in (8) below. The films chosen relate in theme, style, feeling, or budget to the films we propose to produce. It should be noted that these groups do not include films of which the results are known but that have lost money. In addition, there are neither databases that collect all films ever made nor budgets available for all films released. There is, therefore, a built-in bias in the data. Also, the fact that these films have garnered revenue does not constitute a guarantee of the success of this film.

- The three revenue scenarios shown in Tables 11.7 and 11.8—low (breakeven), moderate, and high—are based on the data shown in Tables 11.3 and 11.4. Likewise, Table 11.9 is based on the comparative films in Tables 11.5 and 11.6. We have chosen films that relate in genre, theme, and/or budget to the films we propose to produce. The low scenario indicates a case in which some production costs are covered but there is no profit. The moderate scenario represents the most likely result for each film and is used for the cash flows. The high scenarios are based on the results of extraordinarily successful films and presented for investor information only. Due to the wide variance in the results of individual films, simple averages of actual data are not realistic. Therefore, to create the moderate forecast for Tables 11.7 through 11.9, the North American box office for each film in the respective comparative tables was divided by its budget to create a ratio that was used as a guide. The North American box office was used because it is a widely accepted film industry assumption that, in most cases, this result drives all the other revenue sources of a film. In order to avoid skewing the data, the films with the highest and lowest ratios in each year were deleted. The remaining revenues were added and then divided by the sum of the remaining budgets. This gave an average (or, more specifically, the mean variance) of the box office with the budgets. The ratios over the five years represented in the comparative tables showed whether the box office was trending up or down or remaining constant. The result was a number used to multiply times the budget of the proposed film in order to obtain a reasonable projection of the moderate box office result. In order to determine the expense value for the P&A, the P&A for each film in the comparative tables was divided by the budget. The ratios were determined in a similar fashion, taking out the high and low and arriving at a mean number. For the high forecast, the Company determined a likely extraordinary result for each film and its budget. The remaining revenues and P&A for the high forecasts were calculated using ratios similar to those applied to the moderate columns. In all the scenarios, and throughout these financials, “ancillary” revenues from product placement, merchandising, soundtrack, and other revenue opportunities are not included in projections.

- Distributor’s Fees are based on all the revenue exclusive of the exhibitor’s share of the box office (50 percent). These fees are calculated at 35 percent (general industry assumption) for the forecast, as the Company does not have a distribution contract at this time. Note that the fees are separate from distributor’s expenses (see P&A in (2)), which are out-of-pocket costs and paid back in full.

- The Cash Flow assumptions used for Table 11.10 are as follows:

- Film production should take approximately one year from development through post-production, ending with the creation of a master print. The actual release date depends on finalization of distribution arrangements, which may occur either before or after the film has been completed and is an unknown variable at this time. For purposes of the cash flow, we have assumed that distribution will start within six months after completion of the film.

- The largest portion of print and advertising costs will be spent in the first quarter of the film’s opening.

- The majority of revenues generally will come back to the producers within two years after release of the film, although a smaller amount of ancillary revenues will take longer to occur and will be covered by the investor’s agreement for a breakdown of the timing for industry windows.

- Following is a chart indicating estimated entertainment industry distribution windows based on historical data showing specific revenue-producing segments of the marketplace:

- Company Overhead Expenses are shown in Table 11.11.