4

The Industry: The Facts and Nothing But

The cinema is an invention without a future.

—LOUIS LUMIÈRE

A Bit of History

Moving images had existed before. Shadows created by holding various types of objects (puppets, hands, and carved models) before a light were seen on screens all over the world. This type of entertainment, which most likely originated in Asia with puppets, was also popular in Europe and the United States. Then in 1877, photographer Eadweard Muybridge helped former California Governor Leland Stanford settle a bet by using a series of cameras to capture consecutive images of a racehorse in motion. Little did he know.

William Friese-Greene obtained the first patent on a moving image camera in England in 1889. Next came Thomas Alva Edison with his kinetograph in 1890, and shortly thereafter, the motion picture industry was born. Edison is widely credited with inventing the first camera that would photograph moving images in the 1890s. Even he did not have a monopoly on moving pictures for long. Since Edison didn’t take out any patents in Europe, the door was open for the Lumière brothers to create the cinematograph, another early form of moving image camera, in Paris in the 1890s. Little theaters sprang up as soon as the technology to project moving pictures appeared. In 1903, Edison exhibited the first narrative film, The Great Train Robbery. Seeing this film presumably inspired Carl Laemmle to open a nickelodeon, and thus, the founder of Universal Studios became one of the first “independents” in the film business. Edison and the equipment manufacturers banded together to control the patents that existed for photographing, developing, and printing movies. Laemmle decided to ignore them and go into independent production. After several long trials, Laemmle won the first movie industry antitrust suit and formed Independent Moving Pictures Company of America. He was one of several trailblazers who formed start-up companies that would eventually become major studios. As is true in many industries, the radical upstarts who brought change eventually became the conservative guardians of the status quo.

Looking at history is essential for putting your own company in perspective. Each industry has its own periods of growth, stagnation, and change. As this cycling occurs, companies move in and out of the system. Not much has changed since the early 1900s. Major studios are still trying to call the shots for the film industry, and thousands of small producers and directors are constantly swimming against the tide.

Identifying your Industry Segment

Industry analysis is important for two reasons. First, it tests your knowledge of how the system functions and operates. Second, it reassures potential partners and associates that you understand the environment within which the company must function. As noted earlier, no company works in a vacuum. Each is a part of a broader collection of companies, large and small, that make the same or similar products or deliver the same or similar services. The independent filmmaker (you) and the multinational conglomerate (most studios) operate in the same general ballpark.

Film production is somewhat different when looked at from the varied viewpoints of craftspeople, accountants, and producers. All of these people are part of the film industry, but they represent different aspects of it. Likewise, the sales specifications and methods for companies are different not only from each other but also from the act of production. Clearly, you are not going to make a movie without cameras, but the ones you may use are changing. Now we have the Red (digital) camera, while other films still are being shot in 35 mm. The business operations of the companies that make equipment are seriously being impacted. The Eastman Kodak Company, founded by George Eastman who put his first camera in the hands of consumers in 1888, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2012.

When writing the Industry section of your business plan, narrow your discussion of motion pictures to the process of production of a film and focus on the continuum from box office to the ancillary (secondary) markets. Within this framework, you must also differentiate among various types of movies. Producing the $140-million Captain America or the $170-million three-dimension (3D) Hugo is not the same as making the $800,000 Winter’s Bone or the $2.5-million Courageous. A film that requires extensive computer-generated special effects is different from one with a character-driven plot. Each has specific production, marketing, and distribution challenges, and they have to be handled in different ways. Once you characterize the industry as a whole, you will discuss the area that applies specifically to your product.

In your discussion of the motion picture industry, remember that nontheatrical distribution—that is, Blu-ray/DVD, free television/cable, pay-per-view, the Internet, and domestic and foreign television—are part of the secondary revenue system for films. Each one is an industry in itself. However, they all affect your business plan in terms of their potential as a revenue source.

Suppose that you plan to start a company that will supply movies specifically for cable or the home video market. Or you plan to mix these products with producing theatrical films. You will need to create separate industry descriptions for each type of film. This book focuses on theatrically distributed films and how all the other revenue sources make up the total of each film. When films bypass theatrical and are sent directly to other media platforms, you have a problem with forecasting for investors. Currently, there are not databases to use. Chapter 6, “The Markets, Part II,” discusses distribution methods that fit this description.

A Little Knowledge Can be Dangerous

You can only guess what misinformation and false assumptions about the film industry the readers of your business plan will have. Just the words film and marketing evoke all sorts of images. Your prospective investors might be financial wizards who have made a ton of money in other businesses, but they will probably be uneducated in the finer workings of film production, distribution, and marketing. One of the biggest problems with new film investors, for example, is that they may expect you to have a contract signed by the star or a distribution agreement. They do not know that money may have to be in escrow to sign the star or that the distribution deal will probably be better once you have a finished film, or, at least, are well into production. Therefore, it is necessary to take investors by the hand and explain the film business to them.

You must always assume that the investors have no previous knowledge of this industry. Things are changing and moving all the time, so you must take the time to be sure that everyone involved has the same facts. It is essential that your narrative show how the industry as a whole works, where you fit into that picture, and how the segment of independent film operates. Even entrepreneurs with film backgrounds may need some help. People within the film business may know how one segment works, but not another. As noted in Chapter 3, “The Films,” it can be tricky moving from working for a studio or large production company to being an independent filmmaker. The studio is a protected environment. The precise job of a studio producer is quite simple: Make the film. Other specialists within the studio system concentrate on the marketing, distribution, and overall financial strategies. Therefore, a producer working with a studio movie does not necessarily have to be concerned with the business of the industry as a whole. Likewise, if you are a filmmaker in another country, your local industry may function somewhat differently. Foreign entertainment and movie executives may also be naive about the ins and outs of the American film industry.

A Snapshot of the Industry

The total North American box office in 2011 was $10.2 billion. The share for independent films was $3.4 billion or 34 percent of the 2011 total. Revenues for North American independent films from all worldwide revenue sources for 2011 are estimated as more than $8 billion. Worldwide box office revenues totaled $32.6 billion in 2011. Projections for 2013 are for the overall filmed entertainment market to reach $45.1 billion in the United States and $102.2 billion worldwide. Once dominated by the studio system, movie production has shifted to reflect the increasingly viable economic models for independent film. The success of independent films has been helped by the number of new production and smaller distribution companies emerging into the marketplace every day, as well as the growing interest of major U.S. studios in acting as distributors in this market. Also, there has been a rise in the number of screens available for independent films.

Investment in film becomes an even more attractive prospect as financial uncertainty mounts in the wake of Wall Street bailouts and international stock market slides. Widely recognized as a “recession-proof” business, the entertainment industry has historically prospered even during periods of decreased discretionary income. Although the North American box office was down four percent in 2011, it is up 14 percent year-to-date. “In mature markets such as the United States, the business can be more cyclical in the short term, driven by product supply and distribution patterns. In the long term, however, domestic revenues continue to grow…2012 looks to be another growth year,” National Association of Theater Owners (NATO) President John Fithian said. Senator Christopher Dodd, Chairman and CEO of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), stated at the December 2011 Asia Pacific Screen Awards, “I am proud to report that the film industry remains a key driver of economic growth around the globe.”

As you go through this chapter, think about what your prospective investor wants to know. When you write the Industry section of your business plan, answer the following questions:

- How healthy is the industry?

- How does the film industry work?

- What is the future of the industry?

- What role will my film play in the industry?

Motion Picture Production and the Studios

The history of Universal Studios shows an interesting change of ownership among foreign conglomerates. In 1990, Japanese conglomerate Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. bought MCA Inc., the parent company of Universal Pictures. After five years of turmoil and disappointing results, they sold MCA/Universal to Canada’s Seagram in 1994, which sold it to French communications/water company Vivendi in 2000. In 2003, Vivendi sold Universal Pictures to American mainstay General Electric. In 2011, cable television company Comcast bought 51 percent of the company, which is now called NBCUniversal. Some foreign companies have hired consultants to do in-depth analyses of certain U.S. films in order to understand what box office and distribution mean in this country.

Another interesting case study is MGM. The once-prominent brand was taken private in 2005 by a consortium of private investors including Sony Corporation of America. After a year, the contract to distribute only Sony films ended and MGM started functioning as an independent distributor with a recent return to funding films. Then, in 2011, the company was rescued from bankruptcy by a new group of private investors and is being run as an independent company by Spyglass Entertainment Co-Chairmen, Roger Birnbaum and Gary Barber. The company cofinances many of its films with studios but also makes its own independent films.

Originally, there were the “Big Six” studio dynasties: Warner Brothers (part of Time Warner, Inc.), Twentieth Century Fox (now owned by Rupert Murdoch), Paramount (now owned by Viacom), Universal (now NBCUniversal), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (now MGM), and Columbia Pictures (now Sony Pictures Entertainment). After the Big Six came the Walt Disney Company. Together, these studios are referred to as “the Majors.” (Note: A good source for the early days of Hollywood is The Moguls: Hollywood’s Merchants of Myth by Norman Zierold.) In most cases, the Majors own their own production facilities and have a worldwide distribution organization. With a large corporate hierarchy making production decisions and a large amount of corporate debt to service, the studios aim most of their films at mass audiences. Although the individual power of each has changed over the years, these studios still set the standard for the larger films.

Until the introduction and development of television for mass consumption in the 1950s, these few studios were responsible for the largest segment of entertainment available to the public. The advent of another major medium, television, changed the face of the industry and lessened the studios’ grip on the entertainment market. At the same time, a series of Supreme Court decisions forced the studios to disengage from open ownership of movie theaters. The appearance of video in the 1970s changed the balance once again. Digitally recorded movies, which are the next big paradigm shift, are discussed at the end of this chapter.

How It Works

Today’s motion picture industry is a constantly changing and multifaceted business that consists of two principal activities: production and distribution. Production, described in this section, involves the developing, financing, and making of motion pictures. Any overview of this complex process necessarily involves simplification. The following is a brief explanation of how the film business operates.

The classic “studio” picture would typically cost more than $10 million in 1993. Or, conversely, seldom could you independently finance above that figure, unless you were a well-known international filmmaker like Ron Howard or Martin Scorsese. Now, there isn’t a real threshold, as independent companies like DreamWorks and Lionsgate are capable of financing movies in the multimillions, thanks to hedge funds and foreign investments. Still, many high-budget films need the backup that a studio can give them. Occasionally, the studio will take a chance on a low-budget film (from their perspective, $20 million) that may not have a broad appeal. However, the studio can spread that risk over 10 to 15 films. Currently, they prefer “tentpole” films; budgets for a single film of this type, like Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, may top $250 million.

The typical independent investor, on the other hand, has to sink or swim with just one film. It is certainly true that independently financed films made by experienced producers and with budgets in the mid-range of $20 to $40 million are being bankrolled by production companies with consortiums of foreign investors. For one entity to take that kind of risk on a single film, however, is not the rule. Besides the production budget, the Print and Advertising (P&A) cost also has to be recouped for a film to break even.

There are four typical steps in the production of a motion picture: development, pre-production, production, and post-production. During development and pre-production, a writer may be engaged to write a screenplay or a screenplay may be acquired and rewritten. Certain creative personnel, including a director and various technical personnel, are hired; shooting schedules and locations are planned; and other steps necessary to prepare the motion picture for principal photography are completed. At a studio, a film usually begins in one of two ways. The first method starts with a concept (story idea) from a studio executive, a known writer, or a producer who makes the well-known “30-second pitch.” The concept goes into development, and the producers hire scriptwriters. Many executives prefer to work this way. In the second method, a script or book is presented to the studio by an agent or an attorney for the producer and is put into development. The script is polished and the budget determined. The nature of the deal made depends, of course, on the attachments that came with the concept or script. Note that the inception of development does not guarantee production, because the studio has many projects on the lot at one time. A project may be changed significantly or even canceled during development.

The next step in the process is pre-production. If talent was not obtained during development, commitments are sought during pre-production. The process is usually more intensive because the project has probably been greenlit (given funding to start production). The craftspeople (the below-the-line personnel) are hired, and contracts are finalized and signed. Because of many lawsuits over the past 20 years over “handshake deals” that seem to indicate otherwise, producers need to strive to have all their contracts in place before filming begin.

Production commences when principal photography begins and generally continues for a period of not more than three months, although major cast members may not be used for the entire period. Once a film has reached this stage, the studio is unlikely to shut down the production. Even if the picture goes over budget, the studio will usually find a way to complete it. In post-production, the film is edited, which involves transferring the original filmed material to digital media in order to work easily with the images. In addition, a score is mixed with dialogue, and sound effects are synchronized into the final picture, and, in some cases, special effects are added. The expenses associated with this four-step process for creating and finishing a film are referred to as its negative costs. A master is then manufactured for duplication of release prints for theatrical distribution and exhibition, but expenses for prints and advertising for the film are categorized as P&A and are not part of the negative costs of the production. Although post-production can last from six to nine months, continuing technological developments have changed the time frame for arriving at a master print of the film.

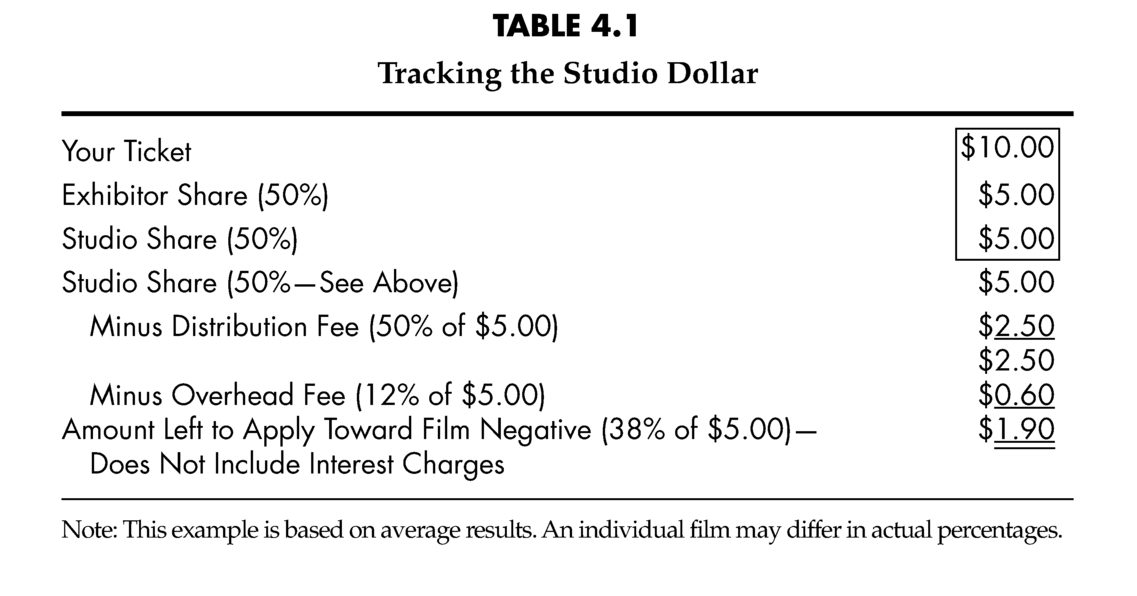

Tracking the Studio Dollar

Revenues are derived from the exhibition of the film throughout the world in theaters and through various ancillary outlets. Studios have their own in-house marketing and distribution arms for the worldwide licensing of their products. Because all of the expenses of a film—development, pre-production, production, post-production, and distribution—are controlled by one corporate body, the accounting is extremely complex.

Much has been written about the pr os and cons of nurturing a film through the studio system. From the standpoint of a profit participant, studio accounting is often a curious process. One producer has likened the process of studio filmmaking to taking a cab to work, letting it go, and having it come back at night with the meter still running. On the other hand, the studios make a big investment. They provide the money to make the film, and they naturally seek to maximize their return.

If your film is marketed and distributed by a studio, how much of each ticket sale can you expect to receive? Table 4.1 provides a general overview of what happens when a finished film is sent to an exhibitor. The table traces the $10.00 that a viewer pays to see a film. On average, half of that money stays with the theater owner, and half is returned to the distribution arm of the studio. It is possible for studios to get a better deal, but a 50 percent share is most common. The split is based on box office revenue only; the exhibitor keeps all the revenue from popcorn, candy, and soft drinks. For all intents and purposes, the distribution division of a studio

is treated like a separate company in terms of its handling of your film. You are charged a distribution fee, generally 40 to 60 percent (we’re using a 50 percent average), for the division’s efforts in marketing the film. Because the studio controls the project, it decides the amount of this fee. In Table 4.1, the sample distribution fee shown is 50 percent of the studio’s share of the ticket sale, or $5.00, leaving 50 percent of the box office revenues still in the revenue stream. Next comes the hardest number to estimate: the film’s share of the studio’s overhead. Overhead is all of the studio’s fixed costs—that is, the money the studio spends that is not directly chargeable to a particular film. The salaries for management, secretaries, commissary employees, maintenance staff, accountants, and all other employees who service the entire company are included in overhead. A percentage system (usually based on revenues) is used to determine a particular film’s share of overhead expenses.

It should be noted that the studios did not make up this system; it is a standard business practice. At all companies, the non-revenue-producing departments are “costed” against the revenue-producing departments, determining the profit line of individual divisions. A department’s revenue is taken as a percentage of the total company revenue. That percentage is used to determine how much of the total overhead cost the individual department needs to absorb.

In Table 4.1, a fixed percentage is used to determine the overhead fee. Note that it is a percentage of the total rentals that come back to the studio. Thus, the 12 percent fee is taken from the $5.00, rather than from the amount left after the distribution fee has been subtracted. In other words, when it is useful, the distribution division is considered to be a separate company to which you are paying money rather than a division of the studio. Using that logic, you should be charged 12 percent of $2.50 ($.30) rather than $5.00 ($.60), but, alas, it doesn’t work that way.

Now you are down to a return of $1.90 or 38 percent of the original $5.00, to help pay off the negative cost. During production, the studio treats the money spent on the negative cost as a loan and charges you bank rates for the money (prime rate plus one to three percent of points). That interest is added to the negative cost of your film, creating an additional amount above your negative cost to be paid before a positive net profit is reached. We have yet to touch on the idea of stars and directors receiving gross points, which is a percentage of the studio’s gross dollar (e.g., the $5.00 studio share of the total box office dollar in Table 4.1). Even if the points are paid on “first dollar,” the reference is only to studio share. If it has several gross point participants, it is not unusual for a box office hit to show a net loss for the bottom line.

Studio Pros and Cons

When deciding whether to be independent or to make a film within the studio system, a filmmaker has serious options to weigh. The studio provides an arena for healthy budgets and offers plenty of staff to use as a resource during the entire process, from development through post-production. Unless an extreme budget overrun occurs, the producer and director do not have to worry about running out of funds. In addition, the amount of product being produced at the studio gives the executives tremendous clout with agents and stars. The studio has a mass distribution system that is capable of putting a film on more than 4,000 screens for the opening weekend if the budget and theme warrant it. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows, Part 2, for example, opened on 4,375 screens. However, I should mention that a very large independent company can have the same clout. Lionsgate opened The Hunger Games on 3,916 screens and increased the release to 4,127 screens the following week. Finally, the producer or director of a studio film need not know anything about business beyond the budget of the film. All of the other business activities are conducted by experienced personnel at the studio.

On the other hand, the studio has total control over the filmmaking process. Should studio executives choose to exercise this option, they can fire and hire anyone they wish. Once the project enters the studio system, the studio may hire additional writers and the original screenwriters may not even see their names listed under that category on the screen. The Writers Guild can arbitrate and award a “story by” credit to the original writer, but the screenwriting credit may remain with the later writers. Generally, the studio gets final cut privileges as well. No matter who you are or how you are attached to a project, once the film gets to the studio, you can be negotiated to a lower position or off the project altogether. The studio is the investor, and it calls the shots. If you are a new producer, the probability is high that studio executives will want their own producer on the project. Those who want to understand more about the studio system should watch fictional treatments of it, such as Christopher Guest’s film The Big Picture, Robert Altman’s The Player, Jeff Nathanson’s The Last Shot, or the “Aquaman” segments in HBO’s series Entourage. Even though Guest’s film was made in 1989, nothing has changed but the names. I also suggest reading some insightful books on the subject from true insiders, such as William Goldman’s Adventures in the Screen Trade and sequel Which Lie Did I Tell?: More Adventures in the Screen Trade, Dawn Steel’s They Can Kill You but They Can’t Eat You, and Lynda Obst’s Hello, He Lied. The studios are filled with major and minor executives in place between the corporate office and film production. There are executive vice-presidents, senior vice-presidents, and plain old vice-presidents. Your picture can be greenlit by one executive, then go into turnaround with her replacement. The process of getting decisions made is a hazardous journey, and the maxim “No one gets in trouble by saying no” proves to be true more often than not.

Motion Picture Production and the Independents

What do we actually mean by the term independent? Defining “independent film” depends on whether you want to include or exclude. Filmmakers often want to ascribe exclusionary creative definitions to the term. When you go into the market to raise money from investors (both domestic and foreign), however, being inclusive is much more useful. If you can tell potential investors that the North American box office for independent films in 2011 was $3.4 billion, they are more likely to want a piece of the action. The traditional definition of independent is a film that finds its production financing outside of the U.S. studios and that is free of studio creative control. The filmmaker obtains the negative cost from other sources. This is the definition of independent film used in this book, regardless of who the distributor is. Likewise, the Independent Film and Television Alliance defines an independent film as one made or distributed by “those companies and individuals apart from the major studios that assume the majority of the financial risk for a production and control its exploitation in the majority of the world.” In the end, esoteric discussions don’t really matter. We all have our own agendas. If you want to find financing for your film, however, I suggest embracing the broadest definition of the term.

When four Best Picture Oscar nominations went to independent films in 1997, reporters suddenly decided that the distributor was the defining element of a film. Not so. A realignment of companies that began in 1993 caused the structure of the industry to change over and over as audiences and technology have continually evolved. A surge in relatively “mega” profits from low-budget films encouraged the establishment of “independent” divisions at the studios. By acquiring or creating these divisions, the studios handled more films made by producers using financing from other sources. Disney, for example, purchased Miramax Films, maintaining it as an autonomous division. New Line Cinema (and its then specialty division, Fine Line Pictures) and Castle Rock (director Rob Reiner’s company) became part of Turner Broadcasting along with Turner Pictures, which in turn was absorbed by Warner Bros. Universal and Polygram (80 percent owned by Philips N.V.) formed Gramercy Pictures, which was so successful that Polygram Filmed Entertainment (PFE) bought back Universal’s share in 1995, only to be bought itself by Seagram-owned Universal. Eventually, Seagram sold October Films (one of the original indies), Gramercy Pictures, and remaining PFE assets to Barry Diller’s new USA Networks, and those three names disappeared into history. Sony Pictures acquired Orion Classics, the only profitable segment of the original Orion Pictures, to form Sony Classics. Twentieth Century Fox formed Fox Searchlight. Metromedia, which owned Orion, bought the Samuel Goldwyn Company, and eventually was itself bought by MGM. Not to be left out of the specialty film biz, Paramount launched Paramount Classics in 1998 (reorganized as part of Paramount Vantage in 2006), and in 2003, Warner Bros. formed a specialty film division, Warner Independent Pictures. Between 2009 and 2011, most of the studio specialty divisions were absorbed and became merely labels.

In 2003, Good Machine, a longtime producer and distributor of independent films, became part of Universal as Focus Features. The company’s partners split between going to Universal and staying independent as Good Machine International. Focus operated autonomously from Universal and was given a budget for production and development of movies by its parent company. Universal, in turn, used Focus as a source of revenue and to find new talent. In 2008, Focus was absorbed into the studio. By the definition used in this book, then, the films produced by Focus would no longer be considered independent; however, it continues to operate as an autonomous division along with Working Title Films.

Then there is DreamWorks SKG. Formed in 1994 by Steven Spielberg, David Geffen, and Jeffrey Katzenberg, the company was variously called a studio, an independent, and—my personal favorite—an independent studio. In the last quarter of 2005, Paramount bought the DreamWorks live-action titles and their 60-title library plus worldwide rights to distribute the films from DreamWorks Animation (spun off as a separate company in 2004) for between $1.5 and $1.6 billion. Paramount then sold the library to third-party equity investors, retaining a minority interest and the right to buy it back at a future date. Spielberg could greenlight a film budgeted up to $90 million, which caused Business Strategies to count films solely financed by DreamWorks as independent. In October 2008, DreamWorks sought a divorce from Paramount and is once again a standalone production company starting life a new as DreamWorks Studios. This means that it is a very large, vertically integrated company that makes independent films. (In the strange lexicon of Hollywood, it is referred to once again as “independent studio.”) Although the studio started with investments upward of $1 million from Reliance and investment companies, it was immediately hit by the 2009 downturn with mixed results. As this edition is being written, DreamWorks looks like it may have a big uptrend with the 2011 Oscar-nominated box office blockbuster The Help.

In-house specialty divisions provided their parent companies with many advantages. As part of an integrated company, specialty divisions have been able to give the studios the skill to acquire and distribute a different kind of film, while the studio is able to provide greater ancillary opportunities for appropriate low- to moderate-budget films through their built-in distribution networks. Specialty labels have proven themselves assets in more literal ways as well. At one point, Time Warner planned to sell New Line for $1 billion (Turner paid $600 million for the company in 1993) to reduce the parent company’s debt load. New Line’s founder Robert Shaye and the other principals had always made their own production decisions, even as part of Turner Pictures. In the summer of 1997, New Line secured a nonrecourse (i.e., parent company is not held responsible) $400-million loan through a consortium of foreign banks to provide self-sufficient production financing for New Line Cinema. Making their own films meant that New Line kept much more of their revenue than they would have if they had been a division of Warner Bros. Everyone liked this situation until the release of The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring, the first film of the trilogy, earned $1.1 billion worldwide, and all three films went on to earn $3.5 billion. In 2007, New Line was taken in-house and made merely a studio label by Warner Bros., which also swallowed up Bob Berney’s Picturehouse and Warner Independent Pictures. Former New Line Cinema chiefs Robert Shaye and Michael Lynne formed Unique Features, a new independent company that plans to produce two to three titles a year. Paramount changed Paramount Vantage from a specialty division to merely a brand name. And Relativity Media bought genre division Rogue Pictures from Universal Pictures for $150 million. Looking at the label as not just a movie brand; Relativity partnered with the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas to launch a clothing line that targets 15- to 25-year olds with hoodies, T-shirts, and hats that will be featured in Rogue’s films and a social networking site, www.RogueLife.com, to promote the label’s films and products. The hotel also will rename its music venue as the Rogue Joint and use it to host film premieres and screenings. As this edition is going to press, the only studio specialty divisions operating independently are Sony Classics, Focus Features, and Working Title Films. The studios do have distribution deals with independent companies, such as Joel Silver’s Dark Castle Pictures and DreamWorks Animation.

As always, new indie production companies have appeared in the last three years. Red Granite Pictures, launched in 2010, got off to a good start with 2011’s Friends with Kids as its first film. Indian Paintbrush has among its films Young Adult, Jeff Who Lives At Home, and Like Crazy. Guns and Roses guitarist Slash started Slasher Film in 2012. XYZ Film is an L.A.-based foreign sales representative that has begun producing films in both the United States and other countries. The Raid: Redemption, released in 2012, is an Indonesian film. These are just a few. To give you a good list, this book would need to be a loose leaf, as companies come and go as film results and economic conditions dictate.

If a film remains independently funded, the prime definition of being an “independent” has been met, no matter which studio distributor’s logo is tacked onto it. It is up to you, the reader, to track what has happened in the meantime. My advice is to spring for the cost of http://www.proimdb.com. It will be a big help.

How it Works

An independent film goes through the same production process as a studio film from development to post-production. In this case, however, development and pre-production may involve only one or two people, and the entrepreneur, whether producer or director, maintains control over the final product. For the purpose of this discussion, we will assume that the entrepreneur at the helm of an independent film is the producer.

The independent producer is the manager of a small business enterprise. She must have business acumen for dealing with the investors, the money, and all the contracts involved during and after filming. The producer is totally responsible from inception to sale of the film; she must have enough savvy and charisma to win the confidence of the director, talent, agents, attorneys, distributors, and anyone else involved in the film’s business dealings. There are a myriad of details the producer must concentrate on every day. Funding sources require regular financial reports, and production problems crop up on a daily basis, even with the best laid plans. Traditionally, the fortunes of independent filmmakers have cycled up and down from year to year. For the past few years, they have been consistently up. In the late 1980s, with the success of such films as Dirty Dancing (made for under $5 million, it earned more than $100 million worldwide) and Look Who’s Talking (made for less than $10 million, it earned more than $200 million), the studios tried to distribute small films. With minimum releasing budgets of $5 million, however, they didn’t have the experience or patience to let a small film find its market. Studios eventually lost interest in producing small films, and individual filmmakers and small independent companies took back their territory.

In the early 1990s, The Crying Game and Four Weddings and a Funeral began a new era for independent filmmakers and distributors. Many companies started with the success of a single film and its sequels. Carolco built its reputation with the Rambo films, and New Line achieved prominence and clout with the Nightmare on Elm Street series.

Other companies have been built on the partnership of a single director and a producer, or of a group of production executives, who consistently create high-quality, money-making films. For example, Harvey and Bob Weinstein created Miramax in the eighties as a video company. Eventually, the company became the 800-pound gorilla by wresting Oscar Best Picture wins away from studio films. In 1993, The Walt Disney Company purchased the company but let it operate essentially independently. In 2005, the Weinsteins negotiated a divorce from Disney but lost the use of their Miramax label and much of the catalog. The Weinstein brothers then created The Weinstein Company, raising $490-million equity in only a few months. Eventually, Disney sold the Miramax label and catalog to private investors. As a newly independent company, Miramax and the Weinsteins work together on many films.

Then there are smaller independent producers, from the individual making a first film to small- or medium-size companies that produce multiple films each year. The smaller production companies usually raise money for one film at a time, although they may have many projects in different phases of development. Many independent companies are owned or controlled by a creative person, such as a writer-director or writer-producer, in combination with a financial partner or a group. These independents usually make low-budget pictures in the $50,000- to $5-million range. Like Crazy and Kevin Hart: Laugh at My Pain-made for $250,000 and $750,000, respectively-are at the lower end of the range, with the former often called “no-budget” and the latter “very low.” When a film rises above the clouds, a small company is suddenly catapulted to star status. In 1999, The Blair Witch Project made Artisan Entertainment a distribution force to contend with, and in 2002, My Big Fat Greek Wedding was a hit for IFC Films (now owned by Rainbow Media) and gave Gold Circle Films higher status as a domestic independent producer and distributor. In 2008, Summit Entertainment, which heretofore had been a foreign sales company, earned more than $400 million with its first production, Twilight, making the company a major independent player. In 2011, however, the company merged with Lionsgate. A reason to keep track of these changes is always to know who the players are. Several of my clients had projects working their way through the management hierarchy at Summit when the Lionsgate deal occurred. They had to wait for the inevitable termination of executives in duplicate jobs, then locate who now had their project. In the worst-case scenario, of course, a project that had been championed by a mid-level executive was sent back to the filmmaker by the next person in the same position.

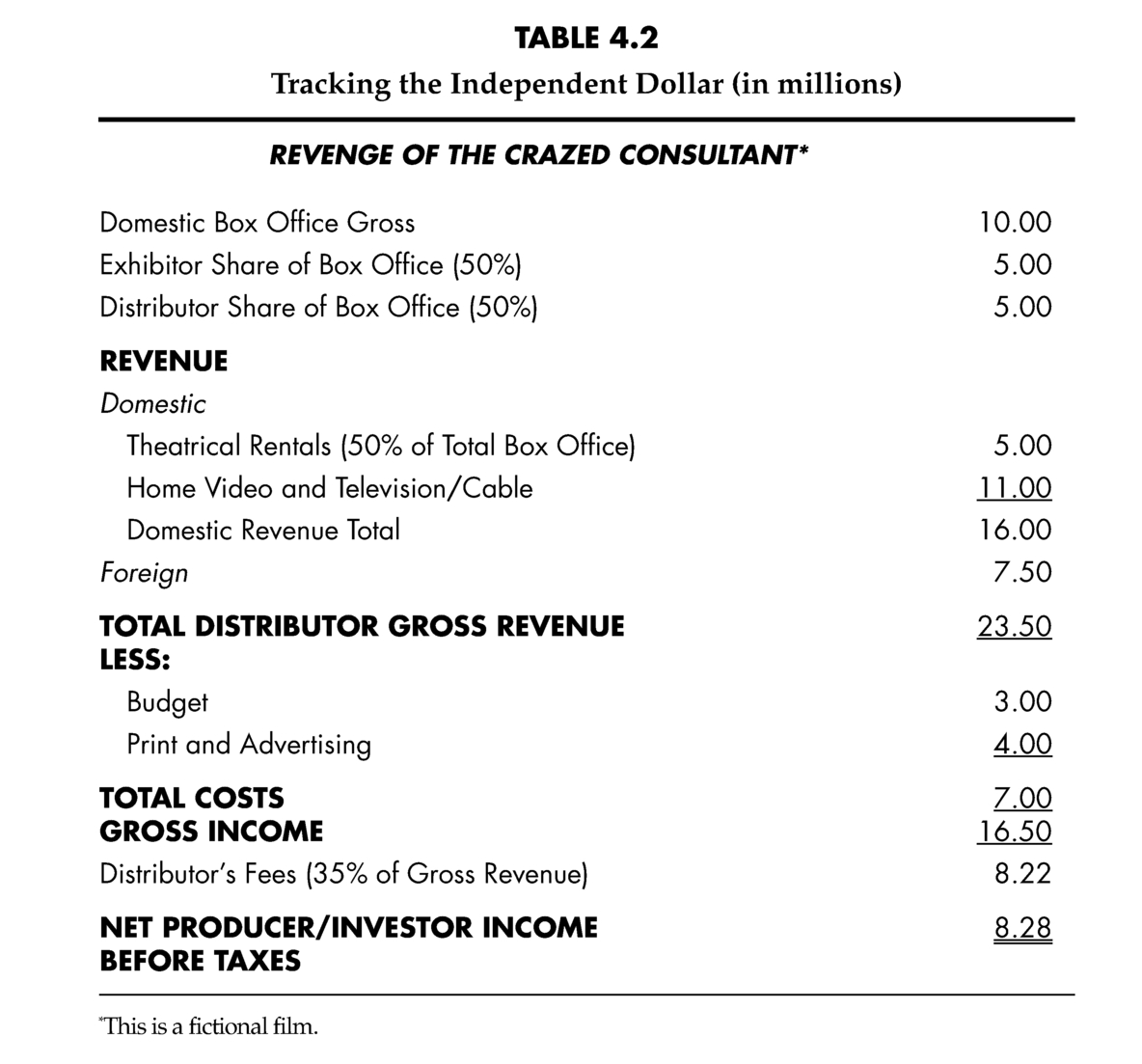

Tracking the Independent Dollar

Before trying to look at the independent film industry as a separate segment, it is helpful to have a general view of how the money flows. This information is probably the single most important factor that you will need to describe to potential investors. I don’t insert this table in plans, as each one has its own forecasts. However, it does serve as a general comparison to the studio system.

Table 4.2 is a simplified example of where the money comes from and where it goes. The figures given are for a fictional film and do not reflect the results of any specific film. In this discussion, the distributor is at the top of the “producer food chain,” as all revenues come back to the distribution company first. The distributor’s expenses (P&A) and fees (percentage of all revenue plus miscellaneous fees) come before the “total revenue to producer/investor” line, which is the net profit.

The box office receipts for independent films are divided into exhibitor and distributor shares, just as they are for studio films (see Table 4.1). Here, the average split between distributor and exhibitor is 50/50. This is an average figure for the total, although on a weekly basis the split may differ. In the example in Table 4.2, of the $10 million in total U.S. box office, the distributor receives $5 million in rentals. This $5 million from the U.S. theatrical rentals represents only a portion of the total revenues flowing back to the distributor. Other revenues added to this sum as they flow in, generally over a period of two years, include domestic ancillaries (home video, which currently encompasses DVD, Blu-ray, and digital sources, plus television, cable, etc.) and foreign (theatrical and ancillary). Whether VOD is included in available figures is not clear.

Technology is rapidly changing, and as it does, the revenue stream for films changes, too. As you may already know, in 2007, the production of VHS tapes ended, although there was still minimal revenue from sales of tapes in 2008. Blu-ray was just beginning to make inroads when the economic collapse temporarily halted its progress. As of mid-2012, DVD is still with us, Blu-ray is growing again, and downloaded films are included in the home video total. However, Microsoft Corporation has announced that their Windows 8, slated for release in late 2012, will not support DVD or Blu-ray discs, signaling the increasing dominance of streaming and downloadable media formats in the home entertainment marketplace.

Film production costs and distribution fees are paid out as money flows in. From the first revenues, the P&A (known as the “first money out”) are paid off. In this example, it is assumed that the P&A cost is covered by the distributor. Then, generally, the negative cost of the film is paid back to the investor. In recent years, filmmakers have paid back from 110 to 120 percent of the budget to investors as an incentive. The distributor takes 35 percent or less of the worldwide revenue as his fee (35 percent is used in forecasting when no distribution deal exists), and the producer and the investor divide the remaining money.

Pros and Cons

Independent filmmaking offers many advantages. The filmmaker has total control of the script and filming. It is usually the director’s film to make and edit. Some filmmakers want to both direct and produce their movies; this can be like working two 36-hour shifts within one 24-hour period. It is probably advisable to have a director who directs and a separate producer who produces, as this provides a system of checks and balances during production that approximates many of the pluses of the studio system. Nevertheless, the filmmaker is able to make these decisions for himself. And if he wants to distribute as well, preserving his cut and using his marketing plan, that is another option—not necessarily a good one, as distribution is a specialty in itself, but still an option.

The disadvantages in independent filmmaking are the corollary opposites of the studio advantages. Because there is no cast of characters to fall back on for advice, the producer must have experience or find someone who does. Either you will be the producer and run your production or you will have to hire a producer. Before you hire anyone, you should understand how movies are made and how the financing works. Whether risking $50,000 or $50 million, an investor wants to feel that your company is capable of safeguarding his money. Someone must have the knowledge and the authority to make a final decision. Even if the money comes out of the producer’s or the director’s own pocket, it is essential to have the required technical and business knowledge before starting.

Money is hard to find. The popular saying is “If it was easy, everyone would be doing it.” Here in Hollywoodland, we get the impression that everyone is. However, that isn’t true in other parts of the country and world. Budgets must be calculated as precisely as possible in the beginning, because independent investors may not have the same deep pockets as the studios. Even if you find your own Megan Ellison (Annapurna Pictures) or Jeff Skoll (Participant Productions) with significant dollars to invest, that person expects you to know the cost of the film. The breakdown of the script determines the budget. When you present a budget to an investor, you promise that this is a reasonable estimate of what it will cost to make what is on the page and that you will stay within that budget. The investor agrees only on the specified amount of money. The producer has an obligation to the investor to make sure that the movie does not run over the budget. Trying to go back to investors for more money after the initial infusion of cash usually doesn’t work.

Production and Exhibition Facts and Figures

The North American (United States and Canada) box office reached $10.2 billion in revenues in 2011, according to the MPAA. The independent share of this box office was $3.4 billion, or 34 percent, as calculated by Business Strategies. The worldwide box office was $32.6 billion. Although U.S. theatrical distribution is still the first choice for any feature-length film, international markets are gaining even greater strength than they had before. New to the picture are VOD releases. Films are beginning to be released day-and-date—in other words, VOD and theatrical on the same day.

Separating the gross dollars into studio and independent shares is another matter. Although databases often include films distributed by specialty divisions of the studios as studio films, being acquired does not change the independent status of the film. In order to estimate the total for independent films, we keep our own database tracking films by financing source and control of production.

Theatrical Exhibition

At the end of 2011, there were 42,390 theater screens (including drive-in screens) in North America with approximately 39,641 in the United States. In the early part of the decade, the companies with multiscreen venues went through bankruptcies and mergers. Despite many ups and downs, such as the advent of the multichannel cable universe and the growth of the home video market, theatrical distribution has continued to prosper.

Film revenues from all other sources are driven by theatrical distribution. For pictures that skip the theatrical circuit and go directly into foreign markets, home video, television, or the Internet, revenues are not likely to be as high as those for films with a history of U.S. box office revenues and promotion. The U.S. theatrical release of a film usually ends between three and five months. The average for both studio and independent films before going into home video generally is four months, although this is slowly becoming closer to three. As with other generally accepted standards, this one is undergoing changes. While studio films begin with a “wide” opening on thousands of screens, independent films start more slowly and build. Rentals will decline toward the end of an independent film’s run, but they may very well increase during the first few months. It is not unusual for a smaller film to gain theaters as it becomes more popular.

Social media has had a big impact on distribution. For independent films, it allows the word to spread faster the first weekend, and successful films to expand more rapidly. For potential studio blockbuster films that depend on a big opening, friends tweeting bad reviews on Friday night can now kill the weekend for the film.

Despite some common opinions from distributors, the exhibitor’s basic desire is to see people sitting in the theater seats. There has been a lot of discussion about the strong-arm tactics that the major studios supposedly use to keep screens reserved for their use. (This is sometimes referred to as block booking.) Exhibitors, however, have always maintained that they will show any film that they think their customers will pay to see. Depending on the location of the individual theater or the chain, local pressures or activities may play a part in the distributor’s decision. Not all pictures are appropriate for all theaters.

Time and time again, independent films that have good buzz (prerelease notices by reviewers, festival acclaim, and good public relations) and favorable word of mouth from audiences not only survive but also flourish. The Visitor is a good example. It started out in a small number of theaters and cities. As audiences liked the film and told their friends about it, the movie was given wider release in chain theaters in more cities. Of course, good publicity gimmicks help. People still ask me if 1999s The Blair Witch Project is a real story; I have even been accused of lying when I say that it is utterly fictional, a “mockumentary” no more real than Borat or Paranormal Activity 1-3.

Digital and 3D

Digital

Digital film is rapidly changing the film industry. While there were 324 digital screens in the United States at the end of 2005 and 5,474 in 2008, there were 25,621 in 2011—13,001 digital non-3D and 12,620 3D—according to the IHS Screen Digest. At the 2012 Cinemacon convention, NATO Chief John Fithian said, “About two-thirds of all screens now have digital projectors, and the transition—as well as the demise of celluloid prints—could be complete by the end of 2013.” He also urged theater owners to check out exhibitors promoting the next stages in the evolution of digital cinema: faster frame rates and laser projection.

On June 5, 2000, Twentieth Century Fox became the first company to transmit a movie over the Internet from a Hollywood studio to a theater across the country. Well, to be more exact, it originated in Burbank, California, and went over a secure Internet-based based network to an audience at the Supercomm trade show in Atlanta. (Trivia buffs, take note: The film was the animated space opera Titan A.E.)

As we roll rapidly through the twelfth year of the 21st century, filmmakers keep calling me about the $30,000 digital film they are going to shoot on their low-cost digital camera that will look like a $10-million film and be distributed on 3,000 screens. Probably not likely on both counts. What is missing in those expectations? For one thing, the filmmaker’s expertise at putting production quality on the screen. That aside, there still is a question about low-budget digital films. It is likely an estimated 1,000 specialty theaters will not be upgraded to digital any time soon due to the expense. The conversion costs to “d-cinema” screens are considerable; each digital projector is $150,000, along with the more than $20,000 per screen required for the computer that stores and feeds the movies. Studios and distributors have been willing to work with the big chain exhibitors to share or even bear the expenses; however, they aren’t concerned about smaller venues.

For most independent filmmakers, it still will be a long haul to the celluloid-free future. Despite the reported number of screens and the number of digital films sent to film festivals, we have yet to find a successful independent film that was distributed in digital format alone. Include money in your budget to convert to 35 mm for exhibition. Don’t assume that the distributor wants to do it. Look at it from his viewpoint. If the distributor is planning on releasing 10 to 20 films a year, and it runs $55,000 or more per film for a quality upgrade from digital to 35 mm, then he is likely to opt for a film that is already in a 35 mm format. “But,” you say, “my film will be so exceptional, he will offer to put up the money.” It is within the realm of possibility, but I wouldn’t want the distribution of my film to rest on that contingency. Or you may say, “I’ll wait until the distributor wants the film, and then I’ll raise the money for the upgrade.” Although this is not out of the question, don’t just assume you will be able to raise the money. Those pesky investors again. Whether it is one investor or several in an offering, you have to go back to those people for the additional $50,000. Will they go for it? Maybe yes or no. If they don’t, then you may be stuck. If you raise the money from additional sources, you still have to get the agreement of the original investors. After all, you are changing the amount of money they will receive from your blockbuster film.

Then there is the question of quality. When technology experts from the studios are on festival or market panels, they always point out that audiences don’t care how you make the film; they care how it looks. In a conversation shortly before the 2009 National Association of Broadcasters in Las Vegas, a Kodak rep told me that experienced filmmakers still prefer to shoot on 35 mm, edit digitally, and then return the movie to 35 mm for the final print. If you can really make your ultra-low-budget digital film have the look of a $5-or $10-million film, go for it. But be honest with yourself.

3D

This section would reasonably be titled “Everything old is new again.” Readers over 60 will remember this technology’s first incarnations in 1952 to 1954, with films like House of Wax (the first with stereoscopic sound) and It Came from Outer Space. It faded in the late 1950s but had a revival in the early 1980s when the large-format IMAX screens offered their early docs in 3Ds. Studios and other production companies discovered 3D in the past four or five years as the “new format” that will revolutionize the film industry. Thanks to improvements in technology, filmmakers can deliver a better product.

It appears that 3D is here to stay. According to a study conducted by Opinion Research Corp., “consumers are savvy in selecting what movies to watch in 3D. They look at it as a more fun, exciting and valuable experience.” However, how many films that audience will continue to pay a premium for each year to come remains to be seen.

Exhibitors are moving ahead converting screens to 3D. In 2011, there were 13,695 (39 percent of the total) digital 3D screens in North America, 11,642 in Europe, 8,116 in the Asian/Pacific area, and 2,026 in Latin America. In the United States, studios have been footing the bill for audiences’ 3D glasses to help push 3D conversion along. As of May 2012, Sony stopped paying for glasses, which cost $5.0 to $10.0 million for a major release. If other studios follow suit, either the cost for tickets will rise or moviegoers will have to buy their own.

Future Trends

For six editions of this book, digital and digital 3D were the future. Now they are here. More revolutionary changes in the manner in which motion pictures are produced and distributed are now sweeping the industry, especially for independent films. Web-based companies like Movielink (owned by Blockbuster), Amazon’s Video on Demand (VOD), CinemaNow, and Apple’s iTunes Store are selling films and other entertainment programming for download on the Internet, and websites such as Netflix and Hulu (through Hulu Plus) stream filmed entertainment to home viewers as rentals. New devices for personal viewing of films (including Xbox, Wii, video iPod, iPhone, and iPad) are gaining ground in the marketplace, expanding the potential revenues from home video and other forms of selling programming for viewing. On a local newscast, I recently saw a demonstration of a wristwatch on which you can make phone calls and see text. Will short films be next?

What do you Tell Investors?

All business plans should include a general explanation of the industry and how it works. No matter what your budget, investors need to know how both the studio and the independent sectors work. Your business plan should also assure investors that this is a healthy industry. You will find conflicting opinions; it is your choice what information to use. Whatever you tell the investor, be able to back it up with facts. As long as your rationale makes sense, your investor will feel secure that you know what you are talking about. That doesn’t mean he will write the check, but at least he will trust you.

Tables and Graphs

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but 20 pictures are not necessarily worth 20,000 words. The introduction of user-friendly computer software brought a new look to business plans. Unfortunately, many people have gone picture crazy. They include tables and graphs where words might be better. Graphs made up about three-fourths of one company’s business plan that I saw. The graphs were very well done and to a certain extent did tell a story. The proposal, put together by an experienced consultant, was gorgeous and impressive—for what it was. But what was it? Imagine watching a silent film without the subtitles. You know what action is taking place, and you even have some vague idea of the story, but you don’t know exactly who the characters are, what the plot is, or whether the ending is a happy one. Similarly, including a lot of graphs for the sake of making your proposal “look nice” has a point of diminishing returns.

There are certainly benefits to using tables and graphs, but there are no absolute rules about their use. One key rule for writing screenplays, however, does apply. Ask yourself what relation your tables and graphs have to what investors need to know. For example, you could include a graph that shows the history of admissions per capita in the United States since 1950, but this might raise a red flag. Readers might suspect that you are trying to hide a lack of relevant research. You would only be fooling yourself. Investors looking for useful information will notice that it isn’t there. You will raise another red flag if you include multiple tables and graphs that are not accompanied by explanations. Graphic representations are not supposed to be self-explanatory; they are used to make the explanation more easily understood. There are two possible results: (1) the reader will be confused or (2) the reader will think that you are confused. You might well be asked to explain your data. Won’t that be exciting?