CHAPTER

1

RESULTS AND RELATIONSHIPS

Only Teams That Risk Going Too Far Will Go Far Enough1

Netflix was born of a simple idea—provide movies on DVDs delivered via the U.S. Postal Service.2 This was a radical departure from the approach of the industry leader at the time, Blockbuster, which had more than 9,000 stores filled with rack after rack of videocassettes. The founders of Netflix claimed that they started the company out of frustration with being charged $40 by Blockbuster for a movie rental turned in six weeks late. That story, however, was nothing more than a clever marketing ploy.3 The truth was that the founders, already successful entrepreneurs, wanted to be the “Amazon of something.”4 They saw that DVD players, then rare, would come down in price and become the preferred technology for viewing movies. Netflix even worked with DVD manufacturers and retailers to accelerate that process. Once it occurred, people embraced the Netflix model—one that offered a vast selection of movies online, rapid turnaround of orders, and a simple low-cost fee structure. The bright-red Netflix mailing envelopes were soon appearing in mailboxes across the country. Blockbuster, which in 2000 was 500 times as large as Netflix,5 was slow to respond to the Netflix threat—unable to believe that its greatest asset, a vast chain of retail stores, had become a liability. The decade-long battle between the two firms culminated in Blockbuster’s bankruptcy—a casebook example of a nimble startup company outmaneuvering a much larger and well-established firm.6 Netflix continued to grow and is the world’s leader in the online streaming of movies and TV shows, with more than 83 million subscribers.7 It is now moving aggressively into the production of original content with hit TV shows such as House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black. Netflix, with a track record of taking big risks in the pursuit of growth, will likely become the dominant media company in the world.

Netflix is equally bold in its approach to people management. More than 8 million people have downloaded a presentation of the firm’s operating principles.8 Sheryl Sandberg, CFO of Facebook and author of Lean In, suggests that the Netflix “culture deck” may be the most important document ever produced in Silicon Valley.9 In it, the company describes how it operates and, in particular, its freedom and responsibility culture. Netflix believes in giving its employees a great deal of autonomy but also holding them to high standards of performance. Each year, it strives to do something that reinforces the freedom people have in how they work. For example, Netflix did away with the need for its employees to track their vacation time—they take as much as they need. The key ingredient in making this model work is having the right people. Freedom and responsibility are not worth a great deal if people lack the motivation and capabilities needed to deliver results. Netflix developed its culture deck after the firm’s CEO, Reed Hastings, was dismayed after conducting new-hire orientation sessions where up to one out of three new people were shocked by what he told them about the firm’s high-performance culture (emphasizing, in part, that they operated as a team and not a family and people need to continually earn their place in the company—otherwise, they would be fired). Hastings held some of his hiring managers accountable for not clearly communicating his firm’s culture to those they hired. But he decided that putting the Netflix culture principles in writing would reduce the number of people who wondered, after joining the firm, if they made the right decision. He didn’t want anyone thinking the company had engaged in a “bait and switch.” The culture was not for everyone, and Hastings wanted new hires to be told what to expect.10 The culture deck, as a result, was distributed to all potential hires and, thus, by default, became a public statement. Hastings decided to post it for those interested in how his firm operates.

Netflix uses the term “talent density” to describe the level of skill within a firm. High density is a workforce comprised of people who can perform at a level that Netflix describes as extraordinary. It developed the idea of density after the painful experience of laying off one-third of its workforce early in its history due to insufficient cash flow. The firm retained its most talented people and let go of the others. After the layoffs, the firm’s leadership was fearful that the company would not make progress on its improvement initiatives because the remaining 80 employees would need to focus on simply running the existing business. But, to their surprise, the work to be done was getting done faster and better with far fewer people. Hastings, the CEO, commented, “We tried to figure out why. And we realized now there was no more dummy proofing necessary . . . everybody was going fast and everything was right.”11 A second insight from that period was that those who remained after the layoffs enjoyed working in an environment where everyone could be trusted to do an exceptional job. They wanted to work in a company that consisted only of highly talented people. The joy they felt from this experience was even more than the success that typically resulted from their collective efforts. The company decided then that it would develop an approach to ensure that it retained only extraordinary people moving forward—and not settle for mediocrity in any way.

Netflix believes that most firms suffer from the opposite—which becomes more pronounced as they grow. This occurs because mediocre talent can be tolerated when a firm is successful and has the financial buffer to carry those who are underperforming. In essence, large companies can afford those who are far from extraordinary (versus smaller startup firms that generally don’t have that luxury). Netflix further believes that firms, as they grow, create processes in an effort to compensate for a decrease in talent density. Most large firms, for instance, require annual operating plans and conduct regular operating reviews to ensure that their various groups are focused on the right priorities (versus trusting them to do so more spontaneously). Each functional group (such as finance and human resources) develops its own set of processes with the best intentions, but the cumulative effect can create stifling bureaucracy. The problem is that processes are almost always less effective than talent in surfacing and adapting to emerging business challenges and competitive threats. Processes are based on a set of assumptions about what is needed in a given situation and a particular point in time—which becomes a problem when the assumptions on which those processes are based become outdated as things change in a firm’s marketplace. This is not to suggest that processes are unnecessary—only that processes are no substitute for talent.

Netflix works hard to avoid the trap of putting processes before people. It gives its employees big jobs and ample latitude on how to perform those jobs. It strives to simplify or eliminate the administrative requirements it places on its people. It also works hard to surround its people with talented peers, which the firm believes is the best perk a company can offer employees. All of which is good news if you work at Netflix. The bad news, at least for some, is that Netflix will not only fire underperformers—it will fire those who are only average. Netflix believes that talent ultimately determines who wins in a competitive battle. The company is tenacious in upgrading talent because it believes the output of an extraordinary employee is 10 times that of an average employee. It also believes that the best thing it can offer its employees is the experience of working with other highly talented, highly dedicated peers.

The primacy of talent within its culture impacts almost all of Netflix’s actions when it comes to people management. The company, for instance, recently introduced a generous one-year unlimited sabbatical for employees who are new parents. The program pays the salaries of those who want to spend time at home with their newborns. Their jobs are waiting for them when they return. In announcing the program, Netflix described the program as a means to attract and retain superior talent. It noted that:

Netflix’s continued success hinges on us competing for and keeping the most talented individuals in their field. Experience shows people perform better at work when they’re not worrying about home. This new policy, combined with our unlimited time off, allows employees to be supported during the changes in their lives and return to work more focused and dedicated.12

Netflix is now clear about its expectations—extraordinary performance from every employee. Effort doesn’t matter. Intent doesn’t matter. Results matter. This can mean, at one extreme, that those who produce outstanding results with relatively little effort are rewarded based on the outcome they achieve. On the other extreme, those who work hard but fail to produce results will leave the firm. This doesn’t mean that they are fired after one misstep, but it most likely means they are fired if there is a second misstep. This firm’s approach is all the more striking in that Netflix is competing for talent in a tight labor market. Silicon Valley has a low unemployment rate, with the competition for top-flight engineers being particularly intense. With talent in short supply, we might assume that Netflix would be more accommodating of average performers. Not so. The firm’s emphasis on superior results begins in its orientation sessions with new hires. One employee, responding to a question about the firm’s culture, observed:

I currently work for Netflix—and yes, there is a culture of fear BUT it is pretty much outlined to you on DAY ONE that if you do not perform, they will find you and get rid of you as quickly as possible. So you know what you’re in for as soon as you step in the door.13

Another employee, echoing the same sentiment but with a touch of dark humor, described a mythological “sniper in the building” whose job it is to locate and kill any Netflix employee who fails to deliver extraordinary results.14

Understanding the Netflix approach to talent is summarized in a story that Reed Hastings tells often. Early in his career, Hastings worked for a startup technology firm as an engineer. He would work long hours and neglect some of the more basic office tasks, such as washing out his coffee cups each day. Instead, he let them pile up, and then, at the end of the week, someone took the cups, cleaned them, and returned them to his office. Reed assumed the janitor was washing the cups and putting them back in his office. This went on for over a year until he came in one morning at 5 a.m. and found his firm’s CEO in the bathroom washing Reed’s coffee cups. Hastings was surprised and asked if he was the person washing his cups each week. The CEO said yes and that he did it because Reed was working so hard, including all-night sessions, and the CEO felt this was something he could do to help him. In telling the story, Reed said this small act of kindness made him want to follow the CEO to the ends of the Earth. And here is the story’s punchline—that is exactly where he led the company. The CEO, great with people, was terrible at building products that customers would buy. Hastings’s lesson—people skills are important, but the key is having the judgment needed for a company to be successful. The question that Hastings asks of himself and his managers, particularly in regard to talent, is, what does the company need to promote its growth and what decision is needed to move it forward?

![]()

A second defining trait of the Netflix culture is an ability to look beyond its current business model to the future. The company was planning on being the industry leader in streaming movies online while it was still working hard to win the DVD war with Blockbuster. DVDs were just a stop along the path to streaming. It was planning to produce its own TV shows and movies while it was still a distributor of content being produced by well-established studios. It was planning to expand internationally while it was still working to build a U.S. presence. This firm’s focus on the future is only in terms of its business model—it impacts how it manages its people. Managers are told that their most important job is to build teams that deliver results. Toward this end, Netflix managers are told to periodically question the skills they need on their teams moving forward. The company, in particular, goes to great lengths to ensure that people are well equipped to address not only the challenges of today but also the challenges of the future. The central questions are as follows:

![]() What is it your team will be accomplishing six months from now?

What is it your team will be accomplishing six months from now?

![]() What specific results do you want/need to see?

What specific results do you want/need to see?

![]() How is that different from what your team is doing today?

How is that different from what your team is doing today?

![]() What is needed to make these results happen?15

What is needed to make these results happen?15

After answering these questions, each leader is responsible for addressing any talent gaps in his or her team. In many situations, this means bringing new members into the team with the necessary skills. This stands in contrast to other firms where the emphasis is on developing the existing members of the team through feedback, coaching, and mentoring. Netflix believes that team leaders often fool themselves into thinking that they can develop people who fundamentally lack the skills or temperament needed to be successful. Instead, it asks its managers to recognize when a person does not have the skills needed to be successful. The firm uses what it calls the “keeper test” to set a high standard in determining who stays and who goes. Managers are asked, at least once a year, to “testify” regarding which of their team members they would fight to keep if those people were considering leaving the company to go to other firms. Those whom the manager would not fight to keep should be asked to leave the company.16

The focus in Netflix is not on what you contributed in the past but on what you can contribute moving forward. The firm’s loyalty is to the future, not the past. Those, for instance, who managed the growth of the Netflix DVD business may lack the skills needed to manage the growth of the firm’s streaming business. Those who lead the streaming business may lack the skills needed to drive the production of original TV shows and movies. Those who built the U.S. business may lack the skills to manage the firm’s expansion into international business. Netflix does not believe people should inherit future roles based on past achievements if they lack what is needed to drive future growth. To pay and retain people based on their past performance is bad for the performance of the business. It is also bad for the culture because it indicates, particularly to the new or younger people, that the company is not as performance driven as it claims. This management philosophy goes against the practices of many firms where past achievements are recognized by ensuring future roles within the company. Netflix is different. If you can’t contribute to the firm’s future growth, you are likely out of a job.

Managers, in general, can find reasons to avoid doing the painful work of removing those who are a poor fit to a company’s future needs. This occurs for any number of reasons. First, assessing the capabilities of people is not always an easy endeavor. Truly poor performance is evident, but average performance is more difficult to assess given the range of factors that can influence how a person performs (such as the difficulty of the task, the availability of resources, or the cooperation of other groups within a firm). Second, most managers care about their team members as well as their families. Removing people from their jobs should not be an easy task, and for many leaders, it is the most painful part of their jobs. Third, most supervisors seek to avoid the legal entanglements that can occur when employees are fired or demoted. This is particularly true when there is no paper trail documenting the reasons for removing someone from his or her job (or in striving to justify why they would be a fit for future demands). Finally, many managers believe that they can coach their people to higher levels of performance—even though past supervisors have failed in doing so. They assume that they, unlike others, have what it takes to improve the performance of underperforming individuals.

Netflix strives to overcome these obstacles by taking a different approach, summarized in the provocative statement, “Adequate performance in Netflix results in a generous severance package.”17 The firm realizes that the goal of creating a high-talent-density organization requires an effective way to let go of those who don’t meet its high standards. The challenge is to move out of the company those who don’t fit the firm’s needs in a manner that causes the least amount of damage to the employee, his or her manager, and the company. In an effort to be fair to those let go and to minimize the pain felt by managers who ask people to leave the firm, Netflix offers a generous severance package (which begins at four months of salary even for those who have just joined the firm and is often higher for those with longer tenure). The company also wants to avoid legal action from those let go and thus strives to part with them on terms that are as good as possible.18 A former Netflix human resources leader, who played a key role in building the firm’s unique culture, describes how the firm separates from those who fail to meet its standards:

We want them [the employees] to keep their dignity. . . . In many companies, once I want you to leave, my job is to prove you’re incompetent. I have to give you all the documentation and fire you for poor performance. It can take months. Here, I write a check. We exchange severance for a release. To make Netflix a great company, people have to be able to leverage it when they leave by subsequently getting good jobs.19

The goal for Netflix, and other cutting-edge firms, is to create a culture obsessed with results without creating a culture that is too harsh. What is the point at which a firm or team pushes too far on results and, in so doing, undermines the very outcome it so desires?

![]()

Netflix, of course, is not unique in being obsessed with creating a culture that delivers results. The New York Times recently ran a controversial article profiling the online retailer Amazon.20 In it, the Times lauds Amazon for its success in embracing bold ideas and investing in long-term growth initiatives. Over its history, Amazon has consistently sacrificed near-term profits to fund projects that in some cases take years or even decades to pay off—if at all. In so doing, the firm ignores the pressure from some on Wall Street who want to see it deliver greater profits today. The Times article also compliments Amazon for its culture of candor, where issues are openly debated and people are given ample opportunity to impact the business. But all is not well in Amazon, according to the Times.

The article focuses primarily on Amazon’s cultural weaknesses.21 The company is described as one where people work hard and long, to the point of sacrificing their health and family lives. After interviewing more than 100 current and former employees, the Times authors suggest that it is common for people at Amazon to work during the night, over weekends, and during vacations, answering emails and completing work assignments. The article further suggests that some employees, when taking sick or personal leaves, will come back early for fear of losing their jobs. The result is a higher level of stress than what is found in other firms.22 A second element of the Amazon culture that draws attention is the extensive use of data to assess employee performance. For example, Amazon monitors its distribution employees at a level beyond what is found in most firms. It tags employees with electronic trackers that indicate the route they must follow as they fill orders within the company’s huge multi-acre warehouses. These trackers also give target times for each task and measure if those targets are met.23 The resulting pressure means that those who can’t keep up or are “time thieves” are, in the words of one publication, “pushed harder and harder to work faster and faster until they were terminated, they quit or they got injured.”24

The pressure employees of Amazon feel to perform at the highest level exists in conjunction with an emphasis on operating in a frugal manner—which is seen as important not only to provide customers with low-cost products but as a means to drive innovation. The company believes that people should not simply throw money at the challenges they face but, instead, should think creatively about alternative solutions that may end up being superior. In its statement of leadership principles, frugality is described as the ability to “accomplish more with less. Constraints breed resourcefulness, self-sufficiency and invention. There are no extra points for growing headcount, budget size or fixed expense.”25 That focus, while logical if not admirable, has resulted in some questionable decisions regarding the company’s workforce. For instance, several years ago Amazon built a new distribution facility in Pennsylvania to process and ship online orders. The distribution center was built without air conditioning, saving the company hundreds of thousands of dollars in construction and operating costs. Problems arose when a heat wave hit the area soon after the facility was completed, resulting in difficult working conditions (with temperatures reportedly over 100 degrees inside the facility). Amazon responded by having an ambulance waiting outside, staffed with paramedics for employees who might suffer from heat exhaustion. A local hospital, where a few workers were taken, reported Amazon to federal workplace safety regulators. Several media outlets found out about the conditions at the facility and ran stories with headlines criticizing the firm for its treatment of employees.26 Amazon responded by installing air conditioning at the Pennsylvania distribution center as well as at other locations across the country.

Amazon is further described by the Times as a highly political culture where employees compete for jobs and recognition—a place where some employees will undermine coworkers if it benefits them. Amazon is certainly not unique if politics plays a role in how people behave within the company. Many slow-moving and bureaucratic firms are plagued by politics. But some believe that Amazon has created a more Darwinian, even Orwellian, culture that actively pits people against one another. For instance, Amazon uses a feedback system where people can provide their views regarding the strengths and weaknesses of their coworkers. The Times interviews indicate that this feedback tool is used by some at Amazon to provide negative feedback on those they see as competitors.27 In so doing, they increase their own standings within the firm. The picture painted by the Times, and a number of other publications, is of a company that uses a variety of techniques to get the most of out of its people.

More than 5,000 readers posted comments in response the Times article—the highest number in the paper’s history. Amazon became the focus of an intense debate about its practices and, by implication, what will be or should be the future of the workplace. The reactions fell into one of two camps. Some suggested that the article was unfair in portraying Amazon in an overly negative light. They asked, what is wrong with expecting people to perform at a high level? What is wrong with measuring performance with hard data? What is wrong with spending money in a frugal manner while investing billions to drive long-term growth? They suggest that Amazon, on almost any measure, is one of the great success stories in the history of business. The firm has changed the face of retailing and is growing at a rate that most firms can only envy.28 No firm today can match Amazon’s ability to provide the best selection of products, at the lowest price, and with the fastest delivery. It is branching out into new innovative areas with some notable successes, such as cloud services. The firm has grown each year and now has nearly 240,000 employees, twice as large as Apple and four times as large as Google. The success of the firm’s stock price also suggests that Amazon, at least as viewed by investors, is being built for long-term success.29 It is now one of the 10 largest firms in the world in market value—far beyond the worth of its primary brick-and-mortar competitor Walmart.

Bezos realizes that his company’s culture will not be a good fit for those who prefer a more laid-back environment, one with less aggressive goals and lower performance standards. He openly states that some people may not want to work in an intense environment comprised of driven people who are constantly striving to meet high expectations—their own as well as the firm’s. He noted, “You can work long, hard, or smart, but at Amazon.com you can’t choose two out of the three.”30 That said, Bezos stated that the Times article describes a company that he doesn’t recognize—a firm for which he would not want to work. He argues that his firm’s distinctive culture, built over several decades, is attractive to many who find it, in Bezos’ words, “energizing and meaningful.” Others in the technology industry, as well as current and former Amazon employees, also suggest that the Times portrayal is inaccurate and unfair. In fact, many believe that the “Amazon Way” should not be criticized but instead viewed as a model for other firms—showing how a modern company needs to operate.

Those in the opposing camp, equally vehement in their views, believe that Amazon has created a harsh corporate culture where people, no matter how well paid, are cogs in the firm’s growth machine. Individuals, from the viewpoint of these critics, are brought into the company, worked hard, and then discarded once they burn out or stop providing what the company wants. A former executive at Amazon, who was with the firm for 10 years, recalled a colleague telling her, “If you’re not good, Jeff will chew you up and spit you out. And if you’re good, he will jump on your back and ride you into the ground.”31 The firm’s critics find fault with Amazon pushing performance to the extreme, through a variety of management techniques designed to get the most out of people (such as using employee trackers in its distribution centers). They suggest that Amazon, which generally pays people very well, is attracting new workers because people are naive about the firm’s culture or because a poor economy forces them into jobs they would not take in more favorable times. In short, they view Amazon as a highly successful twenty-first-century sweatshop.

![]()

In the introduction, I outlined five practices of cutting-edge teams (such as fostering a collective obsession and valuing fit over experience). These practices focus on how these teams operate—their particular ways of thinking and behaving. But Amazon and Netflix call into question what firms and their teams need to achieve.32 Defining what constitutes an ideal team outcome is not the same as how teams go about achieving those outcomes. Amazon, in particular, is a fascinating company because it calls into question people’s beliefs regarding the definition of success. Few can deny that Amazon is an extraordinary company on almost any financial, operational, or customer metric. That may be enough for most people—especially its shareholders. The key question, then, is, does a company need to deliver anything beyond results? More specifically, how do we define success for a company and team? What do companies and teams need to achieve, if anything, beyond results? When does the push for results become too extreme and self-defeating?

Let’s start by defining results. Broadly stated, results means that a team delivers what is expected of it by those who benefit from its products and services.33 This is often seen as a team meeting the expectations of its customers or clients. But for many teams, this means meeting the expectations of the organizations for which they work (and, specifically, meeting the expectations of the leaders who run their organizations). These goals can involve financial targets (such as monthly sales), as well as growth targets (such as the percentage of customers using a firm’s products). Amazon, for instance, started a new business providing cloud storage, seeing it as an opportunity to grow outside of its core retailing business. That business is now one of the firm’s fastest growing and most profitable groups, and it may one day exceed Amazon’s retail business in revenues (as it already does in profit). The team responsible for developing this business has clearly delivered results for customers who value the service it provides. The team has also produced results for the company and its shareholders.

Viewing results only in terms of financial outcomes, however, is too limited. In some cases, teams work toward goals beyond, or even in conflict with, revenue and profit. For example, the clothing company Patagonia decided several years ago that it would use organic cotton in its clothing. This was done because producing organic cotton causes less damage to the environment than conventionally grown cotton. Customers were not asking for this change, but the leaders of Patagonia saw it as part of the firm’s environmental mission to extract less of a toll on the planet in the running of its business. As a result, a team within Patagonia was tasked with shifting the company to organic cotton even though the cost of doing so would be significant. This was no simple endeavor, as few suppliers at the time were producing organic cotton. However, the commitment of the company to the environment was so central that it worked with growers to produce organic cotton. Patagonia’s founder noted,

Switching over to organically grown cotton was a really big deal. Once I found out that cotton was the most damaging fiber that we could make clothing out of, I gave the company 18 months to completely get out of making any product with industrially grown cotton. But you can’t just call the fabric supplier and say, “Give me 10,000 yards of organic shirting.” We had to revolutionize the industry.34

Results, then, are much more than simply achieving financial targets—cutting-edge teams achieve results that move their firms closer to their stated reason for being. Achieving results for Patagonia in regard to organic cotton was not simply maximizing revenue or profit. Nor was the goal to gain a marketing advantage in being viewed as an environmentally friendly company (although that was one outcome). Results, in this case, meant taking action consistent with the core mission of Patagonia. Whole Foods is similar to Patagonia in viewing its mission as being more important than the achievement of near-term financial goals. Whole Foods, of course, does measure and reward financial performance. It also maintains that profit is necessary and good in allowing it to broaden the firm’s impact in helping people live better and healthier lives. However, the firm’s leaders believe that an excessive focus on financial performance often results in bad decisions that don’t lead to good outcomes over the long term. The goal, according to the Whole Foods CEO, is to take the right action for the right reasons—which are actions that advance the higher purpose of the firm.35

A final point on results. The need to produce results includes building the organizational capabilities required to deliver those results. In other words, delivering results means that firms and teams develop the skills to deliver what is needed not just next month or next quarter but over the long term. This starts with enhancing the capabilities of the individual members of each team. In some cases, the focus is on developing the skills of existing team members through challenging assignments, training, and coaching. In other cases, such as at Netflix, it means bringing in people with the talent that the firm needs. Capability development also means that companies improve their ability to support their teams. They develop formal and informal processes that their teams need to be successful. Pixar, for example, has created a host of team-friendly practices, such as providing detailed feedback to a film crew as its project progresses. Delivering results, then, is not just delivering on expectations in the short term—it requires continuous improvements in the capabilities of those on the team, the way the team functions as a group, and the environment in which it operates.

For many hard-edge business people, teams exist only to produce results. Other factors are important to the extent that they support or hinder a team’s ability to achieve a desired outcome. In particular, the relationships among team members either enable results when a team “gels” or, on the other extreme, hinder results when factions within the group undermine its ability to operate at a high level. Relationships, from this point of view, are a means to an end—and are not on par with the need to deliver results. The chief designer at Apple, Jony Ives, tells a story about Steve Jobs that illustrates this point.36 Jobs believed that a key to his success was staffing his teams with highly talented people. His role as a leader was then to push them to achieve more than they thought possible. At one point, Jobs was unhappy with the product that Ives and his team were developing. Consistent with his reputation, Jobs was tough on the team in pointing out the product’s flaws. Ives went to Jobs after the team review and suggested a less aggressive approach in giving feedback to his team. Jobs asked why he should soften his approach and be less direct, given the glaring problems with the product. Ives said it was because he didn’t want to undermine the group’s morale. He described the resulting interaction between Jobs and himself:

I remember asking him why it could have been perceived in his critique of a piece of work [that] he was a little bit too harsh. We’d been putting our heart and soul into this. I said, couldn’t we . . . moderate the things we said? And he said, “Well, why?” And I said, “Because I care about the team.” And he said this brutally brilliantly insightful thing, what he said was, “No Jony, you’re just really vain.”. . . . “No, you just want people to like you. And I’m surprised at you because I thought you really held the work up as the most important, not how you believed you were perceived by other people.” And I was terribly cross because I knew he was right.37

Ives told this story out of respect for Jobs’ ability to focus on what was needed to deliver a great product—in particular, his commitment to giving clear, unambiguous, and tough feedback. But, at the same time, Ives stated that his own greatest achievement at Apple was not the creation of the iPhone or any other Apple product. Instead, he was most proud of his design team and its work process. He noted that no one had left his group voluntarily during his tenure. Ives was suggesting that Jobs was both right and wrong in his view of how teams need to operate. Jobs felt that leaders should care only for the quality of the product or service being produced regardless of the feelings of team members (particularly the feelings of team members toward the team leader). Ives, however, feels that the relationships among members are a critical element in producing great results and need to be nurtured accordingly.

![]()

Robert Putnam, a sociologist, is the author of Bowling Alone. In the book, he describes the central role of interpersonal bonds in a society and the forces that are making such bonds less common.38 He uses the term social capital to describe how these relationships operate in a variety of settings, including nonprofit, public, and private organizations. Social capital, in the simplest terms, is the “glue” that connects people together and, in so doing, helps groups, organizations, and society function more effectively. In particular, social capital plays a role in encouraging individuals to support others for reasons other than their self-interest. An example that Putnam highlights is the willingness of people to give their money and time to community food banks. No one forces people to support community organizations, but many do so willingly. In the private sector, Putnam describes another form of social capital in the networks that exist among various companies and leaders in Silicon Valley. These informal networks produce, in some cases, voluntary cooperation among people and companies, which in turn facilitates the development of new technologies. The central premise of Putnam’s book is that interpersonal connections are critical to the health of a society and the success of its various institutions.

A related aspect of social capital is the idea that it is an asset that can be accumulated and then used when needed. For instance, the social capital that has developed within a team can help it withstand the setbacks that occur as it goes about its work—as the relationships among team members produce greater commitment to each other’s success and the success of the group. In contrast, teams lacking in social capital are more likely to fail when facing adversity, as relationships among members are inadequate or even negative, compromising the ability of the group to work toward an effective solution. Social capital, of course, does not guarantee a group’s success, as myriad factors influence performance. But it increases the likelihood of success within a team or firm.39

A vivid illustration of the role played by social capital is found among soldiers on a battlefield. Countries fight wars for many reasons, but soldiers fight primarily for each other. That is, they fight to support the survival of those they interact with every day, versus fighting for an abstract cause such as democracy or freedom or even against a common enemy. The closer the ties among a group of soldiers, the more likely they are to put themselves in harm’s way for each other.40 An analysis of soldier behavior in the Civil War tested this assumption. The researchers Dora Costa and Matthew Kahn sought to determine why more men did not desert on the battlefront. They examined data on the composition of various army units and their desertion rates. The researchers found that a range of factors impacted the willingness of soldiers to fight. But the key was having a closely bound company, in which soldiers shared much in common. That was the single most significant factor in determining a soldier’s loyalty and willingness to fight. They write, “Was it their commitment to the cause, having the ‘right stuff’ high morale officers, or comrades? After examining all these explanations, we find that loyalty to comrades trumped cause, morale and leadership.”41 Their findings suggest that social capital is critically important when seeking to understand the thinking and behavior of soldiers under the most stressful of situations.

Research from the battlefront, particularly from a war fought over 150 years ago, may seem like a stretch in explaining how teams operate in modern corporations. But consider the findings of the Gallup organization in its study of effective organizations. Gallup research indicates that the level of employee engagement in a workgroup, which is the degree to which people are committed to their team and engaged in their work, is highly correlated to the degree to which they believe they have a best friend at work.42 People who indicated that they have a best friend at work were, in general, more positive about their work and their company. The Gallup research found, for example, that those who report having a best friend at work were

![]() 43 percent more likely (than average) to report having received praise or recognition for their work in the past seven days

43 percent more likely (than average) to report having received praise or recognition for their work in the past seven days

![]() 27 percent more likely to report that the mission of their company makes them feel their jobs are important

27 percent more likely to report that the mission of their company makes them feel their jobs are important

![]() 27 percent more likely to report that their opinions seem to count at work

27 percent more likely to report that their opinions seem to count at work

![]() 21 percent more likely to report that at work, they have the opportunity to do what they do best every day

21 percent more likely to report that at work, they have the opportunity to do what they do best every day

At face value, these appear to be absurd findings, particularly when one is seeking to determine the factors that allow a company or team to perform at a high level. As a consultant, I have worked with leaders who receive survey feedback from Gallup and ask, “How does having a best friend impact how my people view the mission of the company or the degree to which their opinions matter at work? Are we running a company or organizing a high-school social?” But these findings make sense if we think of having a best friend at work as an indicator of the strength of social capital within a group. Higher levels of social capital have a positive impact on the general behavior and perceptions of people within a team or organization. In settings with high levels of social capital, people are connected not just by what they think about their company and its leaders—but also by the connections they have at work.43

![]()

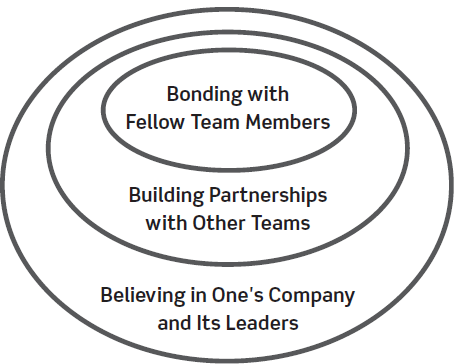

Putnam, in Bowling Alone, suggests there are two types of social capital. Bonding is the connection among members within the same group. Examples include the Whole Foods in-store teams or the Pixar teams working on a film. Building, in contrast, is the connection among people who work in different groups. In this case, people cross group boundaries and collaborate with those in other groups. The members of a product development team, for example, need to work closely with members of a manufacturing team within a company to produce a successful product. A more specific example is found at Pixar, which views collaboration among various groups within the company as essential to the success of a film. The firm has a norm that anyone can talk to anyone else in the company without going through the formal chain of command (which is the norm in many companies). Its belief in the value of interconnectedness even takes on some humorous elements. I was told by an individual who worked for Pixar that people use an expression that underscores how important it is to connect with others: “Good hallway” means that you engage people as you pass them walking through the Pixar headquarters building—you say hello, chat briefly, or at least nod in recognition. He noted, “It is our way of saying that it is important to acknowledge others and help build the community. It also indicates that you are not meek and will reach out to others. Pixar as a company believes in cross-pollination and connecting with others is important to our success.” Putnam argues that both bonding and building are needed to produce a sufficient level of social capital within a society or group. We can add a third type of social capital—believing. This is the connection that people have to the organization that employs them. It is based on the belief that their organization is doing the right things and is worthy of their commitment. This is a connection beyond those within one’s own team and even with those in other teams. It is an emotional investment in the company and its leaders. Social capital, then, consists of three types of relationships:

![]() Bonding with Fellow Team Members: Sustaining relationships involves a range of people-oriented elements of group life, with the most important being the relationships among team members. This includes the ability of team members to gel and produce something greater than the team members could produce working alone. This is not, however, about people simply liking each other. Instead, it involves feeling connected to a group of people who share a common goal.44

Bonding with Fellow Team Members: Sustaining relationships involves a range of people-oriented elements of group life, with the most important being the relationships among team members. This includes the ability of team members to gel and produce something greater than the team members could produce working alone. This is not, however, about people simply liking each other. Instead, it involves feeling connected to a group of people who share a common goal.44

![]() Building Partnerships with Other Teams: Relationships also require that team members work productively with other teams. Note that this involves more than simply being aware of those in other groups—it requires a more personal awareness and investment in the relationship. Much of the literature on teams focuses on the relationships among team members, but the level of relationships with those in other teams is often as important to the group’s success.

Building Partnerships with Other Teams: Relationships also require that team members work productively with other teams. Note that this involves more than simply being aware of those in other groups—it requires a more personal awareness and investment in the relationship. Much of the literature on teams focuses on the relationships among team members, but the level of relationships with those in other teams is often as important to the group’s success.

![]() Believing in One’s Company and its Leaders: This is the connection that people have with their organization—and, in the most positive cases, a belief that their company and its leaders share their values and beliefs. This results in an emotional investment in the firm and its reason for being.

Believing in One’s Company and its Leaders: This is the connection that people have with their organization—and, in the most positive cases, a belief that their company and its leaders share their values and beliefs. This results in an emotional investment in the firm and its reason for being.

Types of Social Capital

To illustrate the role of social capital, consider a team that is developing a new product—let’s say a new smartphone. The new product draws widespread praise and meets its initial sales targets. However, factions developed within the team resulting in a high level of distrust among its members. This made it difficult for some members of the team to work together after the launch of its new product. The team also worked in a highly insular manner, alienating other teams within the company whom they saw as competing for resources and leadership support. The team withheld information from other teams and hoarded resources to maximize its own success. The product development team came to view its company as being led by “corporate suits” who didn’t understand their product or provide the support it needed. Team members felt that they achieved success in spite of the obstacles placed in their way by the company and its leadership. As a result of these factors, the product development team disbanded after the launch, with some members even leaving the company. In this example, the team achieved results on one level but failed to develop social capital needed for the team to sustain its success over time.

Social capital is typically viewed as less important than the achievement of results (at least in a business setting). There are several reasons this occurs. First, survival is job one for organizations, and they depend on their teams to deliver. Motorola, for example, sold a popular cellphone called the RAZR but needed a new generation of smartphones that could compete with the products being offered by its rivals. The next-generation Motorola phone arrived late and without the features it needed to be successful.45 Blame for that outcome goes to the design team responsible for the phone as well as the larger Motorola organization, which failed to provide the guidance and support the team needed. The firm never recovered and was eventually sold to Google. Second, results are typically defined by clear metrics that are in most cases easy to monitor (such as sales or profit). Social capital, in contrast, is fuzzy and hard to measure. Third, results in most organizations are tied to rewards of various types while the quality of the relationships within a team may be recognized but not rewarded. For example, teams that launch a successful product are rewarded financially and otherwise. In contrast, teams that fail to build social capital are typically not held accountable, particularly if they deliver the product. Fourth, efforts to manage relationships within a group or team add complexity to the challenges already facing a team and its leader. This is the case because team members have different motives, styles of operating, and, in particular, ways of dealing with stress and conflict. Relationships, then, are not only difficult to measure but difficult to manage. Even when a leader believes relationships are important, determining how to foster productive relationships is a challenge. For example, what is a leader to do if he or she gets Gallup survey results that indicate that people on his or her team don’t trust each other? Many team leaders, unsure of what to do, resort to superficial team-building events and exercises. Finally, some leaders believe relationships get in the way of making tough calls on people and projects when needed. From this viewpoint, the personal connections in a team have a negative downside in preventing leaders, and others, from being as direct as needed (particularly when a team member is underperforming). In these situations, people can come to value harmonious relationships more than the achievement of results. An example of this is a team leader I know who is good at managing his team members until he has worked with them for a while—then he is less objective in how he views them and, in particular, their performance—and less willing to move them if they are underperforming.

Relationships are important because in the best situations they enable results. This is the Pixar experience, where the ability of team members to work collaboratively is critical to a film’s success. Positive relationships within a team or company can also be an asset in attracting and retaining a talented workforce (as most people want to work in a company culture that is challenging but also supportive). There is, however, a more basic argument regarding the need for strong relationships within organizations and teams. The history of industry shows us that practices that were once voluntary (such as a 40-hour work week, safe working conditions, and minimum wages) are now mandatory. These changes were not made because they enhanced results. In fact, many if not most were resisted by a significant number of people in the business community because they added costs. Many firms complied because they were forced to do so as a result of legislation or because they wanted to conform with emerging social norms. The opportunity for people to connect with others in groups of various types is a basic human need. People want to be a part of communities where they form bonds with others. The opposite, in the more extreme form, is social isolation—which extracts a heavy toll.46 Beyond one’s family, the workplace is now the most important environment for many people—and for some, their workplaces are even more important than their families. Many people spend more of their waking hours at work than at home. Providing people with a work environment that meets their relationship needs may become an obligation that, while not mandated, is expected. In contrast, the controversy surrounding Amazon’s culture results from what some argue is a punishing or even hostile work environment. Providing people with a sense of community is not typically described as a goal in itself—but perhaps that will be the case in the future. Is it unreasonable to assume that more companies will come to believe, like Whole Foods or Zappos, that they have obligations to provide individuals with work environments that enhance their lives and, in particular, provides them with a sense of community? This is not, of course, meant to suggest that relationships come at the expense of results. It is, however, meant to propose that relationships at work will increasingly be more than a means to an end.

The results/relationship model of team life is supported by a number of studies that examine social perceptions. In one group of studies, researchers found that people assess others based on two primary dimensions: competence and warmth. People with the skills and drive needed to achieve a desired outcome are deemed to be competent. People who are supportive of others and helpful are deemed to be warm. These two factors are “the basic dimensions that, together, account almost entirely for how people characterize others.”47 Those who want to be viewed positively by others must be both warm and competent (or at least viewed as such). Moreover, the researchers found that the perception of another’s warmth appears to be the first criteria in judging them—as people assess the intentions of others (their warmth) before determining their ability to carry through with those intentions (their competence). While the researchers don’t make this leap, we can assume that teams are viewed in a similar manner by their members. First, people assess if their team is a warm place to work, one with positive relationships, where others will be helpful and supportive. Second, does the team have the capabilities needed to deliver results and be successful?

An unrelated study by Teresa Amabile and her colleagues focused on the factors that enable high performance in organizations, with a particular interest on the role of helping behavior.48 The researchers asked people in the design company IDEO to identify colleagues who helped them in their work and then rate these individuals on three attributes—their competence (ability to perform a job at a high level), trustworthiness (someone that others feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and feelings with), and accessibility (in being available to those who need help). The researchers also asked people to rate randomly selected colleagues who didn’t make their “helper” list. They found, overall, that the highest rated helpers were also those highest in perceived trustworthiness and accessibility. Competence, of course, mattered—it was higher in those viewed as being helpful in comparison to nonhelpers. But competence was not the driving force in who was rated as most helpful. Those who were seen as supportive (in this case, trustworthy and accessible) were viewed as being the most helpful in solving the challenges facing their colleagues.

Results and Relationships = Team Success

Results |

Relationships |

Current Results: The team delivers on the expectations of its customers/clients Future Results: The team builds the capabilities needed to deliver results in the future |

Bonding: The team develops necessary cohesion among its members Building: The team collaborates with other teams in the organization Believing: The team identifies with the organization in which it works |

![]()

Results and relationships, then, are the two essential outcomes that firms and their teams need to achieve.49 But more is not always better. Both results and relationships have potential downsides. For example, a singular and relentless emphasis on results can undermine a team and its performance. This occurs for several reasons. First, a results-obsessed culture can wear out the individuals on a team. The Pixar Toy Story case is an example of pushing results to the point where it becomes destructive to individuals and a team. An excessive drive to deliver can come from the senior leaders of a company, from a team’s leader, or from the team members themselves. In many cases, it is a combination of all three factors. The challenge is delivering results without creating a culture that is too harsh—a culture where people compete with each other in unproductive ways or live in constant fear of losing their jobs. Take the case of Tony Fadell, who was a highly successful executive at Apple before starting the firm Nest Labs (which produces “smart” thermostats, smoke detectors, and security systems). Fadell has a reputation of pushing himself and his people hard—and he delivered at Apple and initially at his own firm.50 Then things started to unravel. One sign of the problems at the company involved the failed integration of Dropcam, a video camera and cloud-computing company that Nest bought in 2014. In short order, one-half of the 100 Dropcam employees who came to Nest with the acquisition resigned. The founder of Dropcam said that Nest, and Fadell in particular, crushed his group’s ability to build great products. His critics described Fadell’s management style as highly aggressive and controlling—to the point of alienating many of those responsible for developing his firm’s new products.51 Fadell, however, has no regrets. He proudly notes that his leadership style is one of “holding people to a higher standard than they thought they could achieve and pushing them beyond what they thought they could achieve.”52

An excessive emphasis on results can also embolden people to cross ethical and legal boundaries. That is, there are some who will cut corners or even break the law in a desire to produce results for themselves and their company. They do this for self-serving reasons (they reap the financial and career benefits of meeting their goals) and because of pressure from the top of the company (they fear being fired if they fail to deliver). The recent Volkswagen (VW) scandal appears to be an example of this dynamic. Emissions tests were deliberately rigged by staff in the firm’s engineering group to deliver on VW’s aggressive sales targets—which were part of a larger strategy to make the automaker the largest in the world. VW, as a result, installed stealth software in its diesel cars that created false emissions readings. This allowed the company to market cars that performed well for customers while appearing to meet regulatory requirements. The company’s deception, undetected for years, has resulted in the largest class-action settlement in history (totaling more than $14.7 billion in the United States alone). As with many organization failures, the culprit appears to be the culture of the company. VW is a tough, some would say arrogant, firm where mandates are issued from the top and those in middle-management positions feel they have no choice but to find a way to meet those expectations. The diesel engineers didn’t have a way to meet the requirements of their senior leaders, so they developed an unethical workaround. The company fired the engineers who committed the fraud, and a number of senior leaders, including the CEO, have resigned or been fired. The question remains, however, whether the culture of the firm will fundamentally change as a result of this scandal.53

A second case of results being pushed too far involves the pharmaceutical company Valeant. The company is currently in turmoil as a result of questionable distributor practices and financial reporting. Its stock has imploded, and various regulatory groups, including the U.S. Senate, are examining how it operates. The firm has hired a new CEO and is reviewing its business practices. In a press release announcing these changes, it noted, “The company has determined that the tone at the top of the organization and the performance-based environment at the company, where challenging targets were set and achieving those targets was a key performance expectation, may have been contributing factors resulting in the company’s improper revenue recognition.”54 VW and Valeant are not unique. In any given month, one can find stories in the Wall Street Journal about a company, or more often about a team within a company, acting in unethical ways to enhance financial results. The founder of the Chinese Internet commerce company Alibaba, Jack Ma, describes this as a “wild dog” culture where people use dishonest means to gain an advantage for their firms. In an interview, he noted that these companies have an inherent weakness: “Yes, it’s true they make more money, but the money is from dishonest dealings, and may cost the company in the long run. When that generation becomes company leaders, the company will be weak because they get used to being dishonest and taking advantages.”55 Relationships, like results, can also be pushed too far. In particular, strong interpersonal bonds among teammates can lead to increasingly negative outcomes for a team. The first potential downside of overly cohesive groups is that members are prone to groupthink. Research indicates that teams of people who are close interpersonally are more likely to converge in their thinking and more limited in considering alternatives in addressing the challenges they face. Also, they are more likely to be overconfident in their course of action and less inclined to fully appreciate the risks they face moving forward.56 A related downside of an overly cohesive group is the avoidance of tough or contentious issues within the group.57 One study, for example, examined the relationship between social ties and performance in a group of travel agents. The researchers found that interpersonal relationships among the travel agents, when taken too far, eroded a team’s performance. This was determined by examining the ties among workers based on the frequency of their email exchanges over a period of one year. The strength of the interpersonal ties was then correlated to the sales results of each team. The findings indicate that the teams with very little social cohesion had lower performance than average groups. This is not surprising, as there was little bonding among the members (which would have helped enhance their collective learning and performance). But the most interesting finding of the study was that stronger interpersonal ties increased team performance only to a certain point, and then performance began to decline. The researchers suggest that social ties, if very strong, can become more time consuming and important than the performance of the team.

Close interpersonal bonds can also result in people being overly protective of those in their own group, even when they act in inappropriate or unethical ways. Myriad studies suggest that loyalty to the group has a strong impact on people’s willingness to surface unpleasant truths and even unethical acts. In these situations, loyalty to the team becomes more important than dealing with problems or concerns. In case after case, some team members don’t come forward with concerns because they want to be accepted by their group. An overly cohesive group, then, increases the possibility that members are less likely to confront tough issues that, once surfaced, would disrupt the social relations within the group or result in others perceiving “truth-telling” individuals as being disloyal to the team.58

Another liability of close interpersonal bonds is the creation of in-groups and out-groups. Teams with tight bonds can develop an in-group mentality that, to varying degrees, excludes others. Those excluded may be people within the team who are seen as less capable or important. An in-group mentality can also impact how team members interact with those in other groups, whose support is often needed for a team to be successful. The bonds among team members can become so strong that they result in viewing others as outsiders who are not to be trusted. Take, for example, the experience of a past CFO at the clothing company Patagonia. He reported that he came to feel like an outcast within his new company because he didn’t have the history and close interpersonal connections that existed among the firm’s other senior leaders. This condition was compounded by the fact that he didn’t live in the same neighborhood or socialize outside of work with his senior-level peers. “I liked my work, but my personal life was separate,” he recalls. “There was a lot of pressure to be a Patagoniac. I hated that term, and I hated the concept.” Failing to develop a close relationship with those running the company, he eventually departed.59

Finally, an overemphasis on relationships can result in emotional overload. Research indicates that people, in general, have a limited supply of empathy, and a relationship-focused culture will place more demands on connecting with others. An emphasis on relationships can result in what some call “compassion fatigue,” where a great deal of energy is expended in building and maintaining relationships.60 Research further suggests that organizations can place an unequal burden on women in the area of relationship management. This occurs because women, based on social norms, are viewed by many as being more communal and caring than men. As a result, they are expected, although it may never be stated as such, to do more of the work of building and sustaining relationships at work. Some refer to this, when it impacts the workplace, as emotional labor. This work requires taking the time to ensure that people connect with one another and do what is needed to ensure that the work environment fosters collaboration. The end result can be that women, particularly if relationships are emphasized within a company, become burdened more than men in building relationships. Logic suggests that both and men and women would be equally engaged in relationship building at work—the reality, however, may be otherwise. The downside for women is that they may be expected to do relationship work that is time consuming and often unrecognized.61 In one study, for example, scholars Madeline E. Heilman and Julie Chen found that women were rated more harshly if they didn’t help another, in contrast to their male counterparts. They also received less “credit” when they did help a colleague—in part because they were expected to do so. Adam Grant and Sheryl Sandberg, commenting on this study, note, “Over and over, after giving identical help, a man was significantly more likely to be recommended for promotions, important projects, raises and bonuses. A woman had to help just to get the same rating as a man who didn’t help.”62

The Logic and Limits of Results and Relationships

The Need for Results |

The Need for Relationships |

•Team meets the current expectations of the organization and customers •Team builds the capabilities needed to deliver results in the future |

•Cohesion among team members •Collaboration with other teams •Belief in the company and its leaders |

The Risks of Excessive Results |

The Risks of Excessive Relationships |

Increased potential for . . . |

Increased potential for . . . |

•Burnout of team members •Bruising organizational culture •A results-at-any-cost mentality |

•Team groupthink •Avoidance of tough issues •In-group/out-group dynamics |

Teams face two essential risks in managing the results/relationships polarity. The first is that a team will push either results or relationships too far and suffer the consequences of being too extreme. This sometimes occurs because of what some describe as an “either/or mentality” in a team or its leaders.63 In this case, a team views either results or relationships as the primary or only goal and, as a result, pays insufficient attention to the other side of the polarity. There are teams that act with a “results only matter” mentality and teams that act with a “relationships only matter” mentality. One goal of recognizing the importance of both is to determine how each can be pursued in the most effective manner. There is no cookbook or step-by-step formula that can be followed to deliver results and build relationships. Take, for instance, the process of removing those who are underperforming. A company may work very hard to hire the most capable people and give them everything they need to be successful (training, peer support, feedback, . . .). But there are inevitably cases where mistakes are made and people don’t have the drive or skill needed to perform at the highest level. However, removing these people is difficult in a culture that emphasizes relationships. An Airbnb employee noted,

We have a community culture, a “we all get along” culture, which is unique and powerful. Airbnb is the most people-centered company I have seen over my career in the tech industry. However, one problem with our culture is that poor performers are often allowed to stay in the firm. They are transferred to another group or given a less important job. This occurs because managers don’t want to be seen as someone who fires people. Managers know what is going on with their poor performers but will not take action. This hurts the morale of those who are working hard and having an impact.64

Other firms, such as Netflix, move quickly in making the tough call on those who can’t deliver what is needed. These companies believe that successful firms often stumble and in some cases fail because they avoid facing the reality that their talent levels are below what they need to win in a competitive marketplace. You might assume, then, that the best approach is to act decisively when talent gaps are identified within a group. However, Pixar takes a different view. It believes that acting too quickly creates unproductive fear within the workplace, as people are wondering if they will be next to be fired. This distracts people from the work and, in particular, undermines their creativity. Pixar believes a company is better served by waiting until the need to remove an underperformer, even when that person is the team’s leader, is recognized by everyone on the team. At Pixar, this often means removing a director from a film whose team has already come to the conclusion that the director must go. Then the decision to remove the director is supported without creating undue anxiety.65 You might assume, then, that it is best to wait a bit longer than needed to remove underperforming talent. The best time to remove talent depends on a number of factors, and each approach has its own risk. Some leaders move too quickly and create unproductive anxiety in those who remain on the team. Some leaders move too slowly and put the team at risk. Each leader needs to weigh these considerations and determine, given the work to be done and the nature of the team, the proper timing and approach to making necessary changes.

The opposite risk, which I find more prevalent as a management consultant, is that many teams do not push results and relationships far enough and, as a result, fail to achieve what is needed for them to grow. This occurs in some cases because teams strive to manage the results and relationships dilemma by maintaining an acceptable balance between the two—avoiding extremes in either area. That is, they strive to achieve enough results and enough relationships to be successful (or at least avoid failure) but not so much that it creates problems.66 This tactic, while understandable, can result in an equilibrium trap. In this situation, the team strives to maintain a steady state between results and relationships despite challenges that require it to move beyond the status quo in how it manages one or both. Teams in this situation strive for stability and predictability in a world that is often unstable and highly competitive.

Cutting-edge teams avoid falling into the equilibrium trap by pushing both results and relationships to the extreme. Then they manage the very real downsides of doing so. Progress requires moving between these two extremes, sometimes simultaneously, but often in one direction and then the other, depending on the conditions that exist and the needs of the team. In either case, the team acts, for some period of time, as if only results matter or as if only relationships matter. In essence, they ask, “What actions would we take as a team if only results mattered?” Or, on the other extreme, they ask, “What actions would we take if only relationships mattered?” The outcome is a productive dialectic—a constant and healthy tension between results and relationships within a team. The leaders of these teams recognize that one side of the polarity can’t be pursued for long in the absence of the other. Progress, however, is not achieved by being less aggressive in each area. Instead, it is made by pushing both results and relationships to the breaking point.

Pushing the extremes, when done skillfully, creates virtuous or upward cycles in teams. These are situations where achieving results in a team enhances relationships and, in turn, where relationships enhance results. This is the opposite of destructive or downward cycles, where a decline in a team’s results undermines relationships, which become strained as the pressure mounts to turn around the team’s performance. There are also situations where relationships deteriorate to a point of undermining the ability of the team to produce results. The goal, of course, is to create virtuous team cycles where results and relationships operate in a manner to produce ever higher levels of team performance.

TAKEAWAYS

TAKEAWAYS

![]() The fundamental dynamic in teams is delivering results while building relationships. Every team faces the challenge of doing both.

The fundamental dynamic in teams is delivering results while building relationships. Every team faces the challenge of doing both.

![]() In many cases, results and relationships are synergistic—each supporting the other and producing virtuous cycles (where results enhance relationships and relationships enhance results).

In many cases, results and relationships are synergistic—each supporting the other and producing virtuous cycles (where results enhance relationships and relationships enhance results).

![]() In some situations, however, results and relationships are antagonistic, with extremes in one undermining the other. An excessive focus on results can erode relationships; an excessive focus on relationships can erode results.

In some situations, however, results and relationships are antagonistic, with extremes in one undermining the other. An excessive focus on results can erode relationships; an excessive focus on relationships can erode results.

![]() Many teams strive to manage the interplay between results and relationships by maintaining an acceptable equilibrium—enough results and enough relationships to move the group forward without taking undue risk.

Many teams strive to manage the interplay between results and relationships by maintaining an acceptable equilibrium—enough results and enough relationships to move the group forward without taking undue risk.

![]() Striving for equilibrium, however, is a seductive trap. It can result in stagnation as a team seeks to maintain a comfortable balance between results and relationships in an environment that requires more of each.

Striving for equilibrium, however, is a seductive trap. It can result in stagnation as a team seeks to maintain a comfortable balance between results and relationships in an environment that requires more of each.

![]() Genius, in teams, is found at the edges. Cutting-edge teams push results and relationships to the breaking point with an understanding of the need to manage the risks that come with doing so.

Genius, in teams, is found at the edges. Cutting-edge teams push results and relationships to the breaking point with an understanding of the need to manage the risks that come with doing so.