CHAPTER 5

Constant Proportion Portfolio Insurance

5.1 INTRODUCTION TO PORTFOLIO INSURANCE

Portfolio insurance is a family of investment strategies designed to give the investor the possibility to limit downside risk while benefiting from rallying markets. These strategies protect the investor from falling markets and allow him to recover his initial capital or less commonly a percentage of it. One well-known portfolio insurance strategy is constant proportion portfolio insurance (CPPI). This was introduced by Perold in 1986 for fixed income instruments and by Black and Jones in 1987 for equity instruments.

In this chapter, we will introduce CPPI and discuss options on CPPI portfolios. CPPI is a trading strategy intended to keep a constant proportional exposure to a certain risky asset while guaranteeing a minimum value of the portfolio throughout its life. Let us define a strategy as a pair of evolving weights (a(t), b(t)). The portfolio consists of a risky fund denoted RF(t) and a floor denoted Floor(t). The value of the strategy denoted CPPI(t)1 is then given by

![]()

The risky asset could be an equity, commodity, or any other risky underlying. The floor is almost always a bond, either a coupon-bearing bond or a zero bond.

Let us first introduce some standard key words that are commonly used when dealing with CPPIs. Note that this section is essential to the understanding of the rest of the chapter.

CPPI Key Words:

- Floor: The reference level to which the CPPI value is compared; it could be seen as the present value of the protected amount at maturity

- Cushion: CPPI − Floor

- Cushion%: Cushion/CPPI

- Multiplier: A fixed number symbolizing how much leverage we put into the structure; also called the gearing

- InvestmentLevel: The percentage invested in the risky asset portfolio; this is also known as the exposure.

![]()

Allocation Mechanism The rebalancing of the money between the risky asset and the riskless bond is done in the following way:

The investment level is computed first as follows:

![]()

And the CPPI index value is then computed as follows:

![]()

This algorithm corresponds to the most basic CPPI in which we do not have any special features. This will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

The CPPI itself is a hybrid underlying and needs a hybrid modeling framework in order to account for the various risks embedded in it. The risky asset portfolio could itself be a hybrid, as is the case in most of the strategies on hedge funds and mutual funds. Indeed, hedge funds and especially fund of funds do execute investment strategies that involve different types of underlyings.

Moreover, as we will see in section 5.5, flexi-portfolio CPPIs in general and momentum and rainbow CPPIs in particular can be defined on a basket of hybrid underlyings involving various asset classes ranging from equity to interest rates to credit to commodities.

The remainder of this chapter will be organized as follows. First, we discuss the most basic form of the CPPI, the classical CPPI. We then introduce various restrictions and discuss their impact on the CPPI strategy. Pricing and hedging options on the CPPI index is next. Finally, we introduce some nonstandard CPPIs, namely off-balance-sheet, momentum, and perpetual CPPIs.

5.2 CLASSICAL CPPI

The classical CPPI is a self-financing strategy that rebalances the money between the risky asset and the riskless one, depending on the performance of the former, throughout its life. It has the following characteristics:

- The floor is a zero bond whose redemption is the guaranteed capital.

- No restriction is imposed on the investment level.

- No fees are taken out of the CPPI index (see section 5.3.2).

- No ratcheting (lock-in) is applied to the floor (see section 5.3.2).

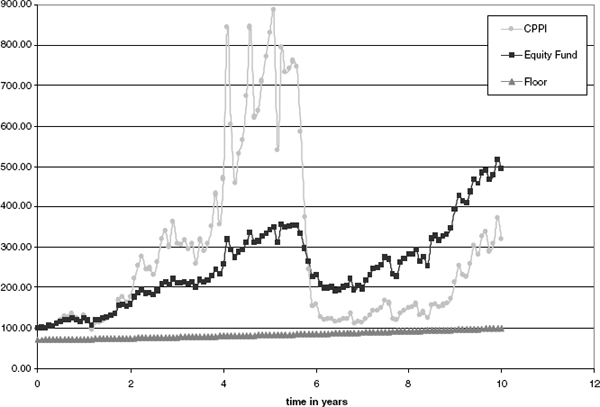

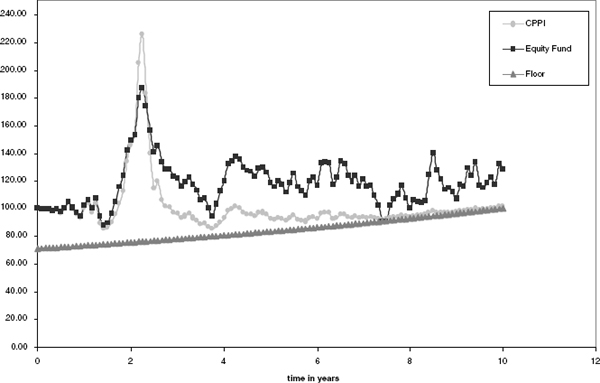

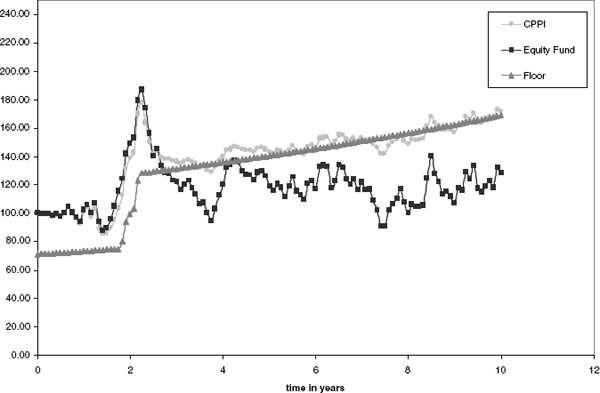

FIGURE 5.1 Example of a simulated CPPI strategy that does not deleverage.

There are other structures that relax the above restrictions and will be discussed later.

When pricing an ATM option on a classical CPPI, the only risk we are dealing with is the gap risk (assuming, of course, that we don't have any liquidity issues).

The Gap Risk In extreme market conditions, the CPPI index could rapidly fall below the floor before the insurance manager has the chance to rebalance his portfolio. The CPPI index will not have a chance to recover, as the investment level will have reached zero and the manager will be unable to repay the guaranteed investment.

It is easily seen that the risky asset has to fall by more than 1/m (m being the multiplier) between two rebalancing dates for the CPPI index to drop below the floor. Moreover, the greater the leverage, the greater is the risk on the fund value to drop at a rate proportional to the leverage as the risky asset falls, allowing correspondingly less opportunity to the fund manager to execute the rebalancing. This means that we have a crash put option with a strike of 1-1/m embedded in the strategy and the strategy is no longer a delta one2 strategy.

The graphs in figures 5.1 and 5.2 give examples of simulated outcomes of a classical CPPI strategy: It can be seen from figure 5.2 that any upside gains made by the strategy at the beginning fade away as soon as the risky asset drops, the investment level can become zero, and the strategy will not recover. A series of restrictions may be added to the classical CPPI strategy in order to allow the investor to benefit from any upsides whenever they happen, even in cases where the classical CPPI would have completely deleveraged.

FIGURE 5.2 Example of a simulated CPPI strategy that deleverages completely.

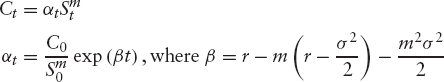

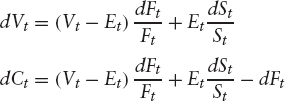

The Continuous Time Classical CPPI If we consider a continuous time strategy with no constraints on the floor or investment level, the pricing of options on a CPPI resembles the one of power options. To illustrate this, let's call Vt and Ft the values of the CPPI index and the floor at time t, respectively. We can therefore write

![]()

where we have V0 = 1, Fmaturity = 1, Vt = Ct + Ft, Et = mCt and dFt = rFtdt, where Ct is the cushion at time t. The variation of the latter is given by:

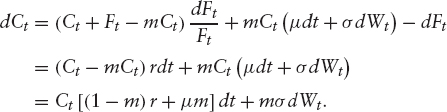

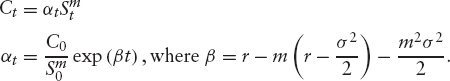

Assuming that the risky asset St is log-normal, dSt = St(μdt + σdWt), we have the following result3

Finally, the value of the portfolio is given by

![]()

This result means that in the limit of continuous trading an option on the CPPI strategy is nothing other than a power option on the risky asset. However, the rebalancing in most CPPI strategies is not continuous, and moreover most of them contain one or more restricting features. In the next section we present the most common restrictions imposed on the classical CPPI strategy.

5.3 RESTRICTED CPPI

The traditional CPPI strategy can be restricted or modified depending on the appetite and whim of the investor. In this section, we examine some of the modifications that may be made. Typically, these are motivated by risk aversion, legal constraints, or performance.

5.3.1 Constraints on the Investment Level

In this section, we depart from the classical CPPI by introducing restrictions on the fraction of the fund that may be invested in the risky asset, and we look briefly at the implications on the CPPI and ATM options on the CPPI.

Minimum Investment Level As mentioned previously, if the risky asset falls substantially and the investment level becomes zero, there is no chance for the strategy to recover. To allow the strategy to pick up from a downturn, a minimum level of investment in the risky asset may be imposed (also called minimum delta).

From the graph in figure 5.3 we can see that the CPPI index is not guaranteed to end above par due to the minimum investment level restriction. This risk of not recovering the initial investment implies that the value of an ATM option on the CPPI index will increase. Indeed, the increase in the probability of not guaranteeing the initial capital will increase the option value.

Maximum Investment Level A maximum investment level is sometimes imposed on the CPPI strategy in order to reduce the gap risk and avoid an unbounded leverage. In a classical CPPI, as the risky asset rises, the investment level becomes greater and greater (the gearing effect) and the CPPI index becomes more like the pure risky asset. As an example, in the case of the underlying risky asset being a mutual fund or a basket of mutual funds, the investment level is capped at 100% due to legal restrictions.

5.3.2 Constraints on the Floor

In the previous section, the implications of restrictions on the investment level were considered. Restrictions or modifications may also be placed on the other component of the CPPI fund, the floor. We examine those in the current section.

FIGURE 5.3 Example of a CPPI strategy with a minimum investment level of 30%.

Ratcheting When the market rallies, any gains made by the CPPI strategy could be lost if a downturn occurs. Therefore, the investor is not guaranteed to benefit from those gains. Ratcheting is introduced to allow the investor to lock in gains made from upside movements of the market.

Ratcheting operates as follows: Whenever the CPPI strategy performs well and reaches a new maximum, a percentage RP of that maximum is guaranteed to the client (we say that we ratchet at RP%). This raising of the floor of the strategy reduces the exposure to the risky asset, introduces a lookback effect to the strategy, and adds, in some cases, more vega to the option by increasing the gap risk.

If we compare figures 5.2 and 5.4, we can see the benefit of ratcheting to the investor. In these graphs, we have looked at the same simulated paths of the risky asset and the guaranteed amount with ratcheting is far bigger than without. In the former case, the floor remains at a low level while on the latter it is raised, taking advantage of the sharp rise in the risky asset early in the life of the strategy.

Protected Fees When an investment manager manages a portfolio such as a CPPI strategy for a client, he will be paid some fees in one way or another depending on the performance of the portfolio. Distributors to retail market also get paid fees for the service.

In the case of a CPPI strategy, fees are usually taken from the CPPI index, but there are cases in which they are taken from the risky asset portfolio. They, then, are equivalent to a proportional dividend on the CPPI index paid at each rebalancing date. These fees are cash amounts paid to the fund manager or to the investor. From the perspective of the investor they are effectively coupons.

Usually, the fees continue to be paid out from the CPPI index even if the latter drops close to or below the floor. This penalizes the CPPI portfolio, as it is likely to end up below par in the case of a classical CPPI, for example. The remedy for this is to protect the fees.

FIGURE 5.4 Effect of ratcheting on a CPPI strategy with minimum investment level of 30%.

When the fees of the strategy are protected, they are often added back to the floor and the latter then becomes a coupon-bearing bond instead of a zero bond. This lowers the investment level, lowers the leverage, and reduces the value of an ATM CPPI option (it is like raising the strike level), which means less gap risk.

Straight-Line Floor Investors wanting to benefit from a drop in interest rates might prefer a straight-line floor, one that varies linearly with time and so does not correspond to a bond as in the classical case. Indeed, as interest rates fall, a bond floor rises and the investment level reduces, which limits the benefit from the risky asset performance (negative correlation between equity and bond prices, when the equity market is doing badly the interest rates are in general cut to boost the economy, inducing a rise in bond prices). Accordingly, stochasticity of interest rates plays a role in the pricing of options on the CPPI index.

In cases in which the investor is relying on an early exit from the strategy, a straight-line floor proves to be effective, as he or she knows with certainty what the level of the floor will be at any time because the floor is insensitive to interest rates.

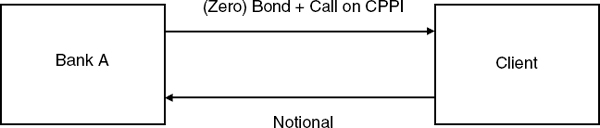

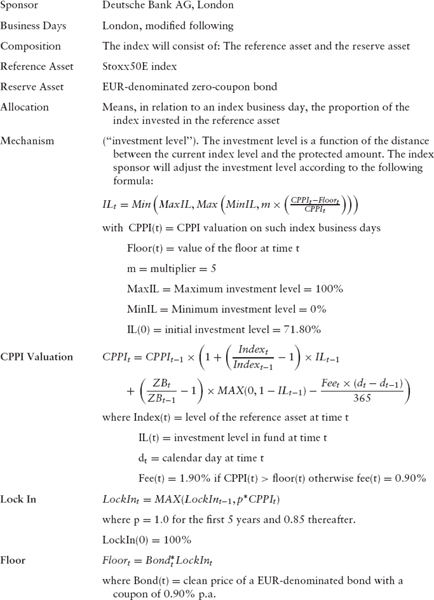

5.3.3 An Example Structure

We consider the structure outlined in figure 5.5 and whose term sheet is presented in section 5.8, appendix C. The risky underlying is Eurostoxx50E and the riskless asset is a coupon bond (protected fees). The ratcheting is applied during the first five years at 100% (to invite more subscriptions) and at 85% thereafter (see section 5.3.2 for more details on ratcheting).

FIGURE 5.5 Example of CPPI structure.

5.4 OPTIONS ON CPPI

5.4.1 The Pricing

The pricing is done within the framework presented in chapter 3, concerning interest rate hybrids. We can add jumps to this framework to account for the gap risk. A Monte Carlo simulation of the strategy is performed. The complexity of the structure imposes the use of different models depending on the risks embedded in the structure.

Indeed, depending on the nature of the underlying risky asset (e.g., a hedge fund vs. a well-known index), the bond floor (emerging markets currency vs. USD or EUR, for example), and the various features contained in the contract, the structure could, for example, be very sensitive to the volatility of interest rates, to jumps in the risky asset, or to both.

Therefore, the model used to price an option on a CPPI index could vary from one structure to another depending on the risks embedded in each structure, as explained above.

5.4.2 Delta, Gamma, and Vega Exposures

An option on a classical CPPI strategy is not a delta one product, as the gap risk introduces optionality. As soon as we introduce restrictions (and fees) on the strategy, we introduce even more optionality. A similar conclusion could be drawn about the vega exposure. Indeed, the vega of an option on a classical CPPI is not zero, precisely because of gap risk, and as soon as we introduce restrictions, we usually increase the vega exposure.

Dividends affect the strategy in a similar way to fees, with the difference being that the dividends are taken only from the risky asset rather than from the CPPI index. This lowers the forward of the strategy, because the risky asset drops, and introduces more vega.

The frequency of rebalancing in a CPPI strategy could be different from the hedging frequency (e.g., monthly rebalancing versus daily hedging), and this creates a large gamma exposure when approaching rebalancing dates.

5.4.3 Hedging

Classical CPPI, if managed correctly and continuously, will always end up at or above the guaranteed level, except if downward jump occurs. An ATM European put on a classical CPPI will not have any value and therefore any greeks. A model incorporating jumps in the risky asset, such as Merton's jump-diffusion model [4] is the only way to price this option (i.e., price the gap risk).

Risk management becomes more qualitative than quantitative. In many cases it is difficult to hedge the greeks given by the model (when the risky asset is hedge funds, mutual funds, etc.). In the case where the CPPI is managed by a third party, the risk manager must ensure that the manager of the CPPI stays within the limits so that the CPPI does not carry additional risk beyond the unavoidable gap risk.

Gap risk can be hedged by selling stability notes. These are basically a series of knock-out OTM Cliquet puts (see section 2.1.6 for more details about Cliquet structures) with a resetting frequency matching that of the CPPI (i.e., daily, weekly, monthly). So the implied gap risk is redefined as a Cliquet put.

In the following section, we depart further from the classical CPPI and present some nonstandard CPPI strategies that use techniques borrowed from the asset management world.

5.5 NONSTANDARD CPPIS

The CPPI strategy is an innovation that comes from the asset management perspective. People often refuse to think of it as a derivative product, and this is why several features, characteristics, and ways of thinking are inspired from there. The fee structure we present here is just an another example of emulating what is done within the fund industry.

5.5.1 Complex Fee Structures

High-Water-Mark Fee Structure The initial motivation behind the development of this strategy is the fact that clients are used to dealing with fund managers who are paid on the relative performance of the fund over a certain period, a year in general, which is well known in the hedge fund industry as high-water mark.4 In this strategy, at every rebalancing date we lock in the highest performance of the CPPI index, and the incentive fees are paid only if the new index level is higher than the previous locked in value. Extra fees are taken on a regular basis, accounting for administrative and running expenses.

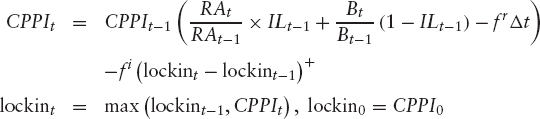

The CPPI algorithm looks like

where fr and fi denote the running and incentive fees, respectively, and RAt, Bt, and ILt denote the values of the risky asset, bond floor, and the investment level, respectively, at a given time t.

Similar to the high-water mark fee structure, structures exist in which the fees are tied to the investment level rather than the CPPI index. The philosophy behind this choice is basically to make the asset manager's earnings linked only to the risks he manages and not to the riskless part of the fund; it is a risk-reward approach.

5.5.2 Dynamic Gearing

The multiplier serves as a leveraging and deleveraging tool and is fixed, in general, for the life of the strategy. Its value is usually between 2.5 and 6, depending on the risky asset. Ideally, one would like to leverage more when the risky asset portfolio is performing well and less for the opposite scenario. This is achieved by exploiting the anticorrelation between the volatility and the performance of the asset, and considering the multiplier as a decreasing function of the realized volatility over a certain period of time (one month in general).

As an example, we can define the multiplier as follows:

![]()

where Volt is the monthly realized volatility for the period [t − 1month, t].

This would decrease the multiplier for a falling market and would prevent it from reaching very high levels in case of a rallying market thanks to the introduction of a cap.

5.5.3 Perpetual CPPI

A perpetual CPPI is, as its name suggests, a strategy in which there is no maturity. This means that the asset manager will be paid a minimum fee even if the strategy does not perform. If the strategy deleverages, no fees are paid until the index bounces back. In case of a massive drop (gap risk), the manager bears the risk and has to ensure that the index is back to the floor level. Then, the index grows, say, at the money market rate and the income generated by the protection asset is put into the risky asset, and the index starts to leverage again, but slowly.

Any early gains made by the strategy are locked in and could be cashed in at any time; hence, this strategy is also known as a fixed threshold strategy. This is advantageous compared to the standard ratcheting strategy in which the client has to wait until maturity to benefit from the performance of the CPPI index. This does, of course, come at a cost as the investor puts some capital at risk as the floor stays at the same level in the case of continuous underperformance of the index.

The CPPI (fund) is an open-end5 structure (fund) that terminates only if the client unsubscribes from the fund or there is not enough money under management. In practice, the fixed threshold strategy is likely to terminate the first time it drops to or below the floor level as the speed of bouncing back is hindered by the fact that it relies on the money market growth for it to leverage again.

The investor avoids interest rate risk by being sure of the amount that he or she is going to cash in at a given time (after any lock-in, the floor is a horizontal line, that is, constant in time), and the only interest rate risk could come from the fact that the underlying risky asset is itself sensitive to the volatility of interest rates.

5.5.4 Flexi-Portfolio CPPI

Actively Managed CPPIs An actively managed fund is a fund in which the risky asset and floor portfolios can change during its life. This is the case for most hedge funds and mutual funds. This means that the asset manager has some freedom in the choice of the underlyings in which to invest. He remains, however, subject to regulatory constraints, especially for mutual funds, as they are typically required to limit their exposure to high-risk assets in order to avoid spectacular losses, as sometimes occurs for hedge funds. However, the asset manager does not have any constraints when it comes to picking his risky portfolio as long as the latter remains within the horizon defined by the regulator or investment guidelines. (See the example of investment guidelines in section 5.8, appendix C.)

An example of actively managed CPPI is the flexi-basket CPPI, which is a strategy where the underlying risky asset is a basket whose underlyings are chosen from a horizon of names. The idea is similar to the cheapest-to-deliver concept, where you do not specify the name of the bond you deliver. The selection of the basket is left to the fund manager, who does the rebalancing of the CPPI portfolio. This enables the asset manager to select the stocks or funds that he or she believes will perform better, taking advantage of the information available during the life of the strategy.

As opposed to actively managed funds or CPPIs where the risky underlying is not known beforehand or can change throughout the life of the strategy, passively managed funds are tied to a predefined set of underlyings that constitute the risky asset portfolio.

Passively Managed CPPIs Passively managed funds follow a predefined investment strategy. The fund manager is literally executing an algorithm, which is designed to take advantage of the performances of the assets in a predefined basket. In what follows, we present the momentum and rainbow CPPI strategies, where the allocation mechanism within the risky portfolio is done following the concept of the classical equity structures, momentum, and rainbow.

Momentum CPPI An example of a momentum structure is an option written on an exotic basket of underlyings, whose payoff at maturity is equal to the initial capital invested plus a geared performance of the underlying basket above some reference level.

Note that we mean by performance the value of the asset at some time in the future compared to its value at the last rebalancing date before this time.

The momentum CPPI is based on the momentum structure philosophy and is intended to imitate the asset manager's behavior and way of payment. Indeed, at each rebalancing date, say monthly, the risky asset of the CPPI is calculated as a weighted sum of the performances, above some reference level, of the various underlyings in the basket. A large weight is assigned to the best performer, the following largest weight to the next-best performer, and the smallest weight to the worst performer. The reference level is in general a one-month interest rate future.

Considering a basket of n underlyings (Si)1≤i≤n and a vector of n ordered weights (wi) such that wn ≤ wn−1 ≤ … ≤ w1, the risky asset value at a given time t

where φ(t) is the last rebalancing date before t and S(i) is the the underlying asset with the ith performance at time φ(t).

Note that if the performance of the underlyings in the basket are below the reference level, they are replaced by the reference level (Libor, Euribor, etc.).

The rebalancing of the momentum CPPI is then done similarly to the classical case in which we have one underlying.

Another strategy similar to the momentum CPPI is the rainbow CPPI. The idea of the rainbow CPPI strategy is likewise based on the classical rainbow structure. The difference between the two strategies, momentum and rainbow, is the fact that in the latter the weights are set and used on the same rebalancing date, whereas in the momentum CPPI, they are set on the previous rebalancing date.

These two structures are very sensitive to the correlation and are appealing for clients who believe in trends. We can incorporate all the features mentioned before, namely ratcheting and minimum investment level, to make the investor benefit from the potential gains made by the strategy at different times throughout its life.

The underlying basket for these structures could range from an all-equity basket to a very diversified one containing, for example, a fixed income index, an equity index, a foreign exchange index, a commodity underlying, a mutual fund, and a hedge fund. Note, however, that in case of small or medium-sized mutual funds or hedge funds, being constituents of the momentum basket, these strategies can disrupt the fund management if the amounts traded are large compared to the size of the funds. For example, if a good performance of the underlying fund in one period is followed by a sharp drop in its value in the next, then the algorithm requires the CPPI manager to buy and then sell a substantial fraction of the fund. This will create serious disruptions within the fund if the amounts traded are substantial compared to the fund's size.

The above strategy ideas could be extended to accommodate some other popular exotic structures containing “worst-off” and/or “best-off” features. The innovation in this field is very rapid in an attempt to respond to the variety of investors and their risk appetites.

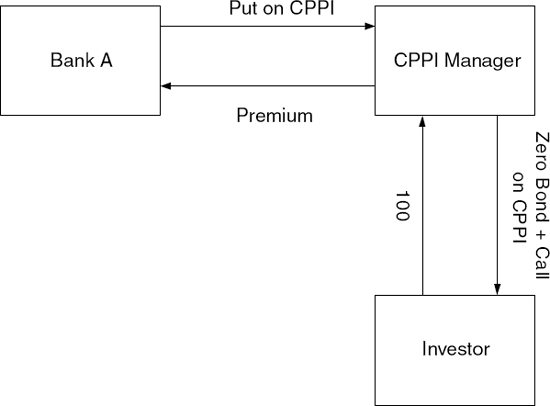

5.5.5 Off-Balance-Sheet CPPI

An off-balance-sheet CPPI is a CPPI strategy managed entirely by a third party. The client is guaranteed a payoff that depends on a fund managed by somebody else, where the latter executes a CPPI algorithm (see Figure 5.6). The liability is there but the assets are not on the books, hence the term off balance sheet.

Regulatory requirements have in part been behind the introduction of this family of CPPIs. Indeed, asset managers and pension fund managers are not allowed to call a fund, portfolio, or product capital guaranteed unless it is really true for all cases. Those institutions are not allowed or unwilling to take the gap risk so they buy the guarantee from outside.

FIGURE 5.6 Example of off-balance-sheet CPPI structure.

On the other hand, after the collapse of Enron and WorldCom, the U.S. accounting standards for derivatives were changed. Profits cannot be taken up front unless they are 100% locked in. A party who sold a CPPI can take the management fees only on an ongoing basis rather than up front, as the structure still bears the gap risk. A purchase of the protection enables the manager of the CPPI to show the profits up front, as all potential risks have been hedged out.

Hedging such exposure is quite tricky, as it is not always easy to trade the underlying fund. Risk management becomes more qualitative than quantitative. In many cases, the manager is not able to hedge the greeks given by the model (e.g., when the risky asset is a hedge fund, mutual fund, etc.). The risk manager must furthermore ensure that the manager of the CPPI stays within the limits so that CPPI does not carry more risk than the gap risk.

A clear reporting line with the CPPI manager needs to be established. The guarantor provides the CPPI manager with the theoretical exposure coming out of the CPPI algorithm, and the CPPI manager must report its portfolio allocation to the guarantor.

In case of early redemption, break clauses need to be negotiated between the guarantor and the CPPI manager. Should the manager not follow the instructions of the guarantor, the guarantee is canceled.

Off-balance-sheet CPPIs can be offered in different forms:

- European or American put on the CPPI

- Bank guarantee on the fund following a CPPI algorithm

- An option embedded in the fund

Usually, the value of the CPPI at time 0 is protected, except when the CPPI strategy contains a ratcheting feature implying a profit lock-in in case the strategy performs well. Then the guarantor guarantees at maturity the amount: LockIn (maturity) − CPPI (maturity).

5.6 CPPI AS AN UNDERLYING

The popularity of the CPPI strategies in the marketplace, the growth of the hedge fund community, and the familiarity of investors with the strategy have resulted in the birth of complex structures treating the CPPI strategy as an underlying itself.

TARNs (target redemption notes, section 4.3) on CPPI are a popular structure. Momentum- and rainbow- type structures can have CPPI indices as their underlyings, to mention a few. Basically, any exotic structure written on classical underlyings, be it equity, interest rates, credit, funds, or commodities could be extended to incorporate CPPI strategies.

5.7 OTHER ISSUES RELATED TO THE CPPI

5.7.1 Liquidity Issues (Hedge Funds)

When a hedge fund is considered as the risky underlying for the CPPI strategy, liquidity issues have to be taken into account, as there is sometimes a large asymmetry in the settlement dates between a buyer and a seller. A buyer settles at T + 5 (meaning that settlement occurs 5 days after the agreement) whereas a seller would settle at T + 30 or T + 60. This makes life difficult for the CPPI manager, as he has to rebalance his portfolio, say, quarterly. This is not an issue when we deal with standard underlyings, as there is no asymmetry and all parties settle at T + 2.

Note that the settlement periods mentioned here are just examples for illustration.

5.7.2 Assets Suitable for CPPIs

The classical CPPI is by nature a self-financing strategy that performs a rebalancing of the underlying portfolio throughout its life, which makes the investor exposed to the realized volatility rather than implied volatility. Therefore, assets with high implied volatility compared to realized volatility are good underlyings for the CPPI strategy. In general, upward trending assets with low volatility (e.g., funds) and no cyclicality are prime candidates as underlyings for a CPPI strategy.

In the case of emerging markets where no mature option market exists, a CPPI strategy is a good instrument that gives access to the upside with very small vega exposure (mainly gap risk). It needs, however, to be engineered, taking into account liquidity constraints and country-specific risk. Diversification is always desirable in order to lower the volatility and the risk of quick deleveraging.

5.8 APPENDIXES

5.8.1 Appendix A

In this section, we give some background on the various types of hedge funds, which are classified based on their investment strategies. Thereafter, we give definitions of some keywords widely employed within the fund community.

Types of Hedge Funds Merger arbitrage: Funds involved in event-driven investments such as mergers and acquisitions and leveraged buy-outs, taking advantage of the fact that the stock of a target company rises and the stock of a buying company depreciates.

High yield: Funds specializing in securities whose underlying companies are in difficulty, which could range from corporate restructuring to inability to honor payments to complete bankruptcy. These funds enter into investment strategies that involve taking opportunistic positions in debt, stock, and credit derivatives on the company.

Convertible arbitrage: This involves managing a portfolio of convertible bonds and hedging the interest rate exposure and equity risk by buying or selling the securities in question (e.g., bonds, stocks).

Fixed income relative value: Funds in which managers try to take advantage of price inefficiencies and mispricings between a related set of fixed income securities and neutralize any interest rate exposure.

Equity arbitrage: Similar to fixed income relative value funds, equity arbitrage fund managers seek to profit from price ineffencies between a related set of equity instruments while neutralizing the risk to directional market movements.

Macro arbitrage: Managers of these funds make forecasts about the shift in world economies and anticipate movements in stock markets, fixed income securities, interest rates, inflation, and foreign exchange due to political changes and global shifts in supply and demand of commodities.

Fund Keywords Open-end fund: Holding a share in an open-end fund is like holding a stock. This is the most common structure, and deals are done on a stock exchange and in a secondary market.

Closed-end fund: A hedge or mutual fund that has stopped accepting subscriptions from investors, at least temporarily, and are traded on a secondary market only by professionals.

Fund of funds: An investment vehicle consisting of shares in various hedge or mutual funds. The vehicle could have a strategy focus, the underlying funds following a given investment strategy, or a diversified one in which the fund managers have different strategies. An investment in a fund of funds offers many structural benefits compared to one in a classic hedge or mutual fund. Indeed, funds of funds offer more transparency and provide frequent portfolio updates. The barrier to entry is another advantage, with levels of minimum investment many times less than single funds being very common. The fee structure is in general complex, as the investor has to pay the incentive and running fees for both the fund of funds and the underlying funds.

Prime brokerage: Large financial institutions often have a prime brokerage group that is dedicated to providing hedge funds with administrative, back-office, and financing services. Other services like providing offices, infrastructure, and initial capital are sometimes offered to help fund managers start their business.

Master feeder fund: A common structure in the United States through which a fund can run two funds, one onshore for U.S.-based investors and another one offshore for non-U.S.-based investors. The underlying funds are called feeder funds, and the father entity is called the master fund. This is created to allow U.S. and non-U.S. investors to have participation in a single fund.

Drawdown: The percentage difference between the maximum and minimum asset values of a fund over a certain period. It is often used as a measure of the risk of a fund.

High-water mark: This is a provision that ensures that the asset manager receives incentive fees only for real profits. He is, in fact, paid only on the basis of the performance attained above the highest net asset value realized previously.

Hurdle rate: The minimum return required from the asset manager. The latter receives incentive fees only for the extra return above it.

Sharpe ratio: Introduced by William R. Sharpe, this is the extra return, above the risk-free one, realized by a fund in units of the risk taken. It is calculated as the difference between the average annualized return and the risk-free rate divided by the annualized volatility of the fund.

Venture capital: Also called capital risk, this is money given to starting funds (start-ups in general) that seek high-return investments.

5.8.2 Appendix B

In this section, we give more details about the computations for the continuous time strategy. Recall that: V0 = 1, Fmaturity = 1, Vt = Ct + Ft, Et = mCt and dFt = rFtdt.

The change in Vt and Ct is given by the following equations:

The log-normality of the risky asset implies

![]()

On the other hand, we know that

![]()

From these two results we can conclude that

Finally,

![]()

5.8.3 Appendix C

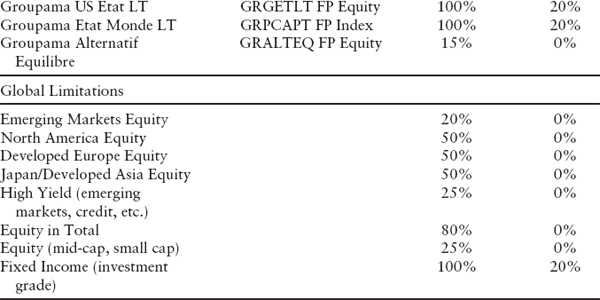

Example of Matrix of Investment Guidelines

Example Term Sheet An example term sheet is given on the following two pages.

Principal Protected Note on CPPI on Stoxx50E

Indicative Terms and Conditions CPPI invests in the reference asset (the underlying fund(s)) and a reserve asset (zero-coupon bond). The allocation between the two is done on a monthly basis following the allocation mechanism. If the CPPI increases in value, it will invest more in the reference asset to increase leverage. If the CPPI decreases in value, it will invest less in the reference asset to protect the capital.

Summary of Terms and Conditions

CPPI on the Stoxx50E

Description of CPPI The CPPI consists of two components: (a) the reference asset and (b) the reserve asset, in different proportions, as determined and computed by the calculation agent. The allocation between (a) and (b) will be performed daily and determined by the allocation mechanism. The allocation will be adjusted to protect the CPPI on the downside and to provide return on the upside.

1 This also referred to as net asset value (NAV).

2 A delta one product is a product whose payoff is linear in the underlying risky asset, a product whose risk could be hedged entirely by the risky asset.

3 See appendix B for details of the computation.

4 See section 5.8, appendix A for the definition of high-water mark.

5 See appendix A for a definition of open-end fund.