Using programme-level student feedback: The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Abstract

This chapter discusses how programme-level student feedback in social sciences is collected in a university-wide process aligned to internal quality assurance (QA) processes. The overall mechanism is designed to support continuous improvement in learning and teaching (T&L) practices and students’ experiences in their undergraduate studies. The chapter also examines the way in which feedback is used in three social science programmes. This comparative study illustrates a diversity in formal and informal processes and practices that reflects the devolved nature of institutions and perhaps specific disciplinary culture. Key attributes evident in the respective continuous improvement processes are highlighted.

Introduction

Feedback is described as a communication process that serves to convey a message from the sender to a recipient (Brinko, 1991). The usual purpose of feedback in an educational context is to improve either student learning or teacher (classroom) performance. Extending such a conceptualisation of feedback, this chapter is a critical reflection on programmelevel feedback, discussed in two broad categories: diagnostic evaluations based on the student learning ‘experience’ and consequent dialogic communications with students and staff as practised in a Hong Kong (HK) university. The purpose of this feedback, which is part of an institution-wide structured QA process based on annual action plans arising from six-yearly programme reviews, and annual programme and course-level monitoring, is to assure and enhance the quality of the educational experience for students. As the university has reported, the measured pace of change has won acceptance and ownership among the teachers and students (CUHK, 2008). Nonetheless, consistent with findings reported in the UK and other countries (Harvey and Williams, 2010), the prioritisation of research tends to create disincentives for the development of innovative learning and teaching processes.

The focus of this chapter is on evaluative feedback and the follow-up consultative process that forms the basis of an iterative improvement in curriculum and T&L. The essence of the approach is in a strategic application of student (and other) feedback to advance desired change through cyclical planning, action, observation and reflection. Consistent with the commitment to quality enhancement as a continuous process, the development of this process and associated procedures has been an iterative one, which has grown and changed as the university has grown in size and complexity. Importantly, this evaluative and consultative process coincides with major changes in the higher education sector in HK. Briefly, these include the introduction of a normative four-year curriculum in 2012, and the shift to an outcomes-based approach to education. The chapter first examines the purpose of programme-level feedback, followed by a brief explanation of the local context. It then explains the types of mechanisms and related processes for collecting (what) and reporting student feedback (how, when and to whom). Finally, the chapter outlines reflections on practice couched in terms of practice in three social sciences undergraduate (UG) programmes. Key attributes in the respective continuous improvement processes are highlighted.

To what end: quality education

Quality assurance is: ‘the means through which an institution ensures and confirms that the conditions are in place for students to achieve the standards set by it or by another awarding body’ (QAA, 2004). The subject has been firmly on the agenda of higher education (HE) institutions for the last 20 years (Blackmur, 2010), mainly as an externally driven process (Brookes and Becket, 2007) and with the caveat that the concept is highly contested (Tam, 2001). Addressing quality in HE, McKay and Kember (1999) suggest that quality enhancement (QE) tends to be less clearly defined, but often more diverse, than QA initiatives. McKay and Kember (1999) also note that the emphasis by internal stakeholders is not so much on QA as on QE, which aims for an overall increase in the quality of T&L, often through more innovative practices. This is consistent with Harvey (2002), who argues that the central focus of quality in HE should be on improving student’s T&L experiences and not on QA reviews conducted by regulatory agencies. That is, enhancement of the student experience is paramount and, allowing for constraints within which individual institutions operate, the task is to provide steady, reliable and demonstrable improvements in the quality of learning opportunities. Characteristics of the respective QA and QE processes are shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1

Characteristics of quality assurance and quality enhancement

| Quality assurance | Quality enhancement |

Source: Swinglehurst, 2008

The mechanisms adopted by internal stakeholders in HE typically include self-evaluation practices and student feedback, as students are an integral part of the learning process (Wiklund et al., 2003). Having outlined the purpose of feedback as enhancement in quality of T&L under the broad rubric of QA, this chapter next turns to understanding the institutional context.

Institutional context

Context is crucial. It explains, for example, the utility of the overarching framework in supporting change. Context, in terms of the devolved nature of the institution and specific disciplinary cultures, can also help explain the diversity that is characteristic in formal and informal practices across programmes. The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) is a comprehensive research-intensive university with a bilingual (Cantonese and English) tradition and a collegiate structure. The undergraduate student body numbers about 11 200, of whom some 10 000 are local HK students. The remainder, about 10–12 per cent, is drawn from the Greater China region, locally termed the ‘mainland’, and the wider Asia-Pacific region, as well as a small number from Europe and the United States. The trend, however, is towards increasing numbers of students from the mainland. This trend is notable for two reasons. First, it introduces complexity in terms of language ability between English, Cantonese and Mandarin, and secondly, it brings together staff and students with vastly different T&L traditions.

T&L is reported as a core function (CUHK, 2008) and the university has understandably evolved explicit systems and processes to ensure and enhance the quality of over 61 and 57 undergraduate and taught postgraduate programmes, respectively. These systems and processes are discussed shortly, but first, the chapter briefly looks at two key cultural influences in HK that have a significant impact on T&L practices in CUHK.

![]() One example is ‘face’ (mianzi) (Ho, 1991; Kim et al., 2006). This abstract and intangible feature of Chinese social psychology is concerned with public image and is crucial in social and interpersonal relationships (Kam and Bond, 2008; Kennedy, 2002). In a T&L context, as Thomas et al. (2011) note, for example, active participation in the classroom and disregard for less visible signals can risk embarrassment and loss of face. Another effect is the tendency not to question people with perceived social status or to see teachers as the sole source of knowledge. These effects can make it seem inappropriate to be too active in class. There can be a similar dissuading impact in consultative discussions with programme managers concerned over public image. The effect is conversations that are polite and passive, rather than exploratory and interactive.

One example is ‘face’ (mianzi) (Ho, 1991; Kim et al., 2006). This abstract and intangible feature of Chinese social psychology is concerned with public image and is crucial in social and interpersonal relationships (Kam and Bond, 2008; Kennedy, 2002). In a T&L context, as Thomas et al. (2011) note, for example, active participation in the classroom and disregard for less visible signals can risk embarrassment and loss of face. Another effect is the tendency not to question people with perceived social status or to see teachers as the sole source of knowledge. These effects can make it seem inappropriate to be too active in class. There can be a similar dissuading impact in consultative discussions with programme managers concerned over public image. The effect is conversations that are polite and passive, rather than exploratory and interactive.

![]() Another notable example of local culture is guanxi, which refers to social networks established between parties in a place of work. A guanxi-bounded network has unspoken assumptions of mutual exchange that must be respected (Luo et al., 2002). The effect is to discourage academics from risking the relationship network within their departments, as this would diminish one’s significance in the group. Overall, as noted by Thomas et al. (2011), local factors have implications for QA and for the feedback process, particularly in the annual programme-level consultative meetings.

Another notable example of local culture is guanxi, which refers to social networks established between parties in a place of work. A guanxi-bounded network has unspoken assumptions of mutual exchange that must be respected (Luo et al., 2002). The effect is to discourage academics from risking the relationship network within their departments, as this would diminish one’s significance in the group. Overall, as noted by Thomas et al. (2011), local factors have implications for QA and for the feedback process, particularly in the annual programme-level consultative meetings.

Collectively, these cultural and other local factors can inhibit the full engagement of programme managers. Gaining access to busy academic staff is the first challenge; gaining their full attention is the next. However, the central issue is in engaging with a relative ‘outsider’ in order to discuss internal-to-programme curricular and teaching staff issues. This is a cultural challenge, as well as a professional one that could be seen as undermining the professional autonomy of academics and programmes by external monitoring and related activity. Overall, effective change involves long-term, evolutionary strategies, particularly as the predominant concern is with research outcomes. Reflecting these complex influences, as Thomas et al. (2011) note, peer-based networks and relationships are crucial, while from a QE perspective, learning needs to be seen as social practice, with greater collaboration between teachers and across disciplines.

Feedback mechanisms and processes

Feedback is usually described as a pivotal part of the learning and assessment process, encompassing developmental and summative feedback to students. As Orrell (2006) has noted, largely because of workload and other demands, students are rarely required to reflect critically and act on feedback. In fact, student response to feedback is largely optional. There are useful parallels to be drawn from these and other observations in literature with programme-level feedback. According to Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick (2006), for example, there is a need to shift the focus to students having a proactive rather than reactive role in generating and using feedback. Another example is the importance of making space for formative assessment in formal curricula, while ensuring also that feedback is appropriate for the development of learning (Yorke, 2003). Hence the problem is course design, not student motivation, and in designing programmelevel feedback, the process must ensure that feedback is reflected and acted upon. Consistent with this imperative, a complex design overlay is evident in, for example, CUHK diagnostic and follow-up dialogic feedback processes.

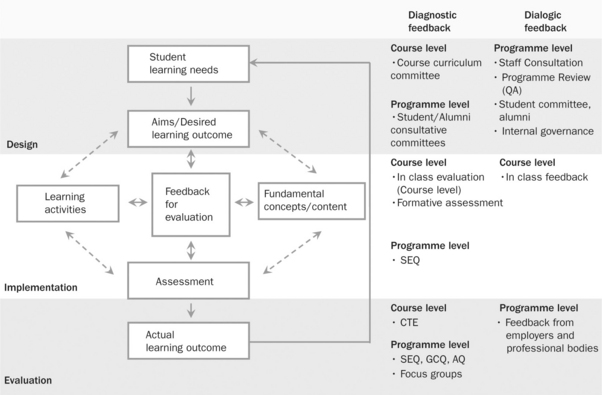

Feedback is a central component in the Integrated Framework for Curriculum Development (Figure 5.1). This framework sets the parameters for the review of both undergraduate and taught postgraduate courses under the oversight of the Senate Committee for Learning and Teaching (SCTL). The focus is an outcome-based approach to learning. Feedback, both diagnostic and dialogic, helps to align the other elements in the model – aims, learning activities, fundamental concepts, and assessments. This systemic process involves course- and programme-level activity across three stages: curriculum design, implementation and evaluation.

The emphasis on outcomes and on performance indicators keeps programmes and the institution accountable. Undergraduate programme indicators include language proficiency in both English and Chinese, numeracy, interpersonal skills and work attitude assessed by annual government-sponsored employer surveys. Other evidence-based indicators include such things as the number of Rhodes scholarships awards and offers by the large accounting firms relative to competitor institutions (CUHK, 2008), although there is a counter view that general employability figures are not a reliable indicator of higher education quality (Harvey and Williams, 2010). Consistent with studies in the UK cited by Harvey and Williams (2010), internal QA and feedback processes at CUHK have a strong disciplinary bias. This issue will become more evident as programmes shift to multi- and inter-disciplinary courses with the intended four-year normative curriculum in 2012, when the challenge for QA will be to assess the multidisciplinary experience of students, rather than the disciplinary identity of staff (Harvey and Williams, 2010).

The dialogic feedback structures illustrated in Table 5.1 include curriculum committees, student and alumni consultative committees, as well as academic advisory systems and as required focus groups. The focus of effort is towards stated educational goals, with the integrated framework helping courses and parent programmes continuously ‘reflect upon practice’ (CUHK, 2008: 37). This reflective process is supported by a multi-layered mechanism of course and programme-level student experience (diagnostic) feedback. However, revealing the influence of local context and in this case the need to facilitate adoption of good practices, there is an understated but necessary sting to the QA process. As the internal CUHK report (CUHK, 2008) notes, programme review outcomes could affect budget allocations; this potential of a negative adjustment depending reported performance adds a powerful cultural and financial incentive to engaging with the process.

Student feedback (how, when and to whom)

A central feature of the internal QA process is diagnostic feedback, which is based on a suite of student questionnaires administered by the university’s Centre for Learning Enhancement and Research (CLEAR). The principal survey is the student experience questionnaire (SEQ), administered at the end of the academic year to first and final year undergraduates. According to Kember and Leung (2005), the SEQ provides comprehensive guidance for curriculum design, with QA assisted through the generation of programme-level profiles in two broad categories: graduate (intellectual) capabilities, such as critical thinking, creative thinking, problem-solving and communication skills, and the T&L environment that includes active learning, teaching for understanding, assessment and coherence of curriculum.

In addition to the annual SEQ, there is an annual graduate capabilities questionnaire (GCQ), administered one year after graduation, and an alumni questionnaire (AQ), administered five years after graduation. These surveys are available in either paper or online (soft copy) modes and in both English and Cantonese, depending on programme choice. Response rates vary from 65 per cent and higher for the in-class paper versions (the preferred option for the SEQ) and the mid-30s per cent for the online version (GCQ). Alumni response rates are noticeably lower (12–28 per cent). However, the overall effect is that the same group of students/alumni is surveyed over a time span of eight to 10 years, depending on the length of the undergraduate programme. This process, which enables longitudinal tracking of student groups, is illustrated in Figure 5.2. If sustained, as well as supporting the immediate needs at programme level, this multi-modal evaluation and feedback process offers good potential to examine the collective effect of educational changes on student learning experiences at an institutional level.

Summary reports for the SEQ, GCQ and AQ (if responses rates are near or over 20 per cent) are sent annually to each programme director and his/her nominated executive team only. The underpinning assumption is a guaranteed level of confidentiality that is central to initial engagement by academic stakeholders with the QA process. Student reflections for a single programme are reported relative to a university mean, allowing the programme to gauge its general performance relative to all other programmes across common metrics for the first and final year study experience. A collated summary of data for the past five years across the two categories for first and final year students, graduates and alumni is also provided.

The annual SEQ report is the basis of internal programme discussions around curriculum development. The report also provides ‘triggers’ for a follow-up consultative meeting with T&L staff, who are designated as faculty liaison officers based on disciplinary background. These annual discussions and consultative meetings focus on student feedback and on devising suitable response strategies if needed. Time and personality-based considerations can influence the establishment of peer networks and relationships. The longer-term aim, consequently, is a trust-based relationship that can be augmented by focus groups and other ad hoc surveys by CLEAR at the request of programmes. As the latter actions tend to be issue-specific and provide descriptive as opposed to evaluative data, they are generally well received by programme staff.

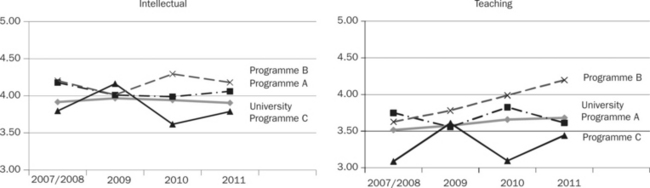

Overall, assuming credible and well-intentioned staff, the process is a time and labour intensive one. Most importantly, in a strategic sense, it is a necessary one that has helped shift cultural reservations and natural defensiveness across undergraduate programmes. The consultative process broadly fits Lewin’s ‘Three-stage Change Model’ (Schein, 1995), providing evidence of the need for change, confronting the situation and reconstructing a new approach, albeit that the process is moderated by careful relationship management. Figure 5.3 illustrates programme-level attainment of outcomes at university level and for the three programmes, which in order to respect programme confidentiality are not identified. While not readily evident in the selected items below in Figure 5.3, there has been a general steady improvement in both reported categories, graduate capabilities and the T&L environment.

Figure 5.3 illustrates a summary of five scales of capabilities related to intellectual development (critical, creative thinking, problem-solving, self-managed learning and adaptability) and four scales related to the teaching environment (active learning, teaching for understanding, assessment and coherence of curriculum). Based on a response scale of 1–5 (where 1 is strongly disagree, 2 is disagree, 3 is neutral, 4 is agree and 5 strongly agree), the respective graphs illustrate trends that provide visual and numeric based information for programmes across the first and final years of undergraduate study, as well as one and five years after graduation (GCQ and AQ). As the graphs show, there is no explicit pattern of changes to intellectual development for the social science programmes under consideration, relative to the university mean. However, it can be seen that Programmes A and B are generally above the mean. In teaching, it is apparent that Programme B students reported a steadily increased level of satisfaction, while Programme A remained slightly above the university mean that has increased over the five years. This suggests that, relatively speaking, students’ satisfaction with Programmes A and B was above average.

Despite Kember and Leung’s (2005) optimistic view on the SEQ providing comprehensive guidance for curriculum development, it cannot be assumed that improvements at programme-level equate to achieving QE at institutional level. There is, for example, a gap between programme level and department and faculty levels, which collectively comprise the university. There is also variable uptake across disciplines, with the hard sciences perhaps more strongly engaged. Nonetheless, consistent with the literature, involving internal stakeholders such as students and academics has helped to embed a culture of quality within most programmes.

Comparative practices in selected programmes

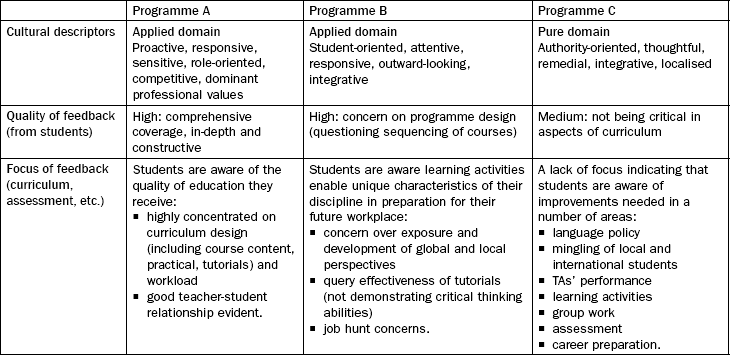

This section examines how feedback and the ‘diagnostic power’ of the SEQ have played out into curriculum and T&L related actions for future development within three programmes in the social sciences. The key component of enacting this diagnostic power is effective dialogic communication, in part shaped by confidence in SEQ data and the quality of follow-up consultations between CLEAR academic staff and programme representatives, and in part by informal communications within programmes. It was apparent that, despite the overarching structure and the use of profiled feedback, there was diversity in the formal and informal processes in programme-level practice. Simply, the experience was that uptake of this feedback was variable, coinciding perhaps with cultural aspects of disciplinary groupings that Becher (1994) has argued transcend institutional boundaries. Sketching a broad four-part rubric, humanities and pure social sciences such as anthropology were identified as tending towards being individualistic, pluralistic, loosely structured and person-oriented, while soft applied social sciences such as education tended to be outward-looking and power-oriented, concerned with enhancement of semi-professional practices. The other two groupings were pure sciences such as physics, and hard applied sciences (technologies) such as mechanical engineering.

Practical considerations for T&L in HE that arose from cultural aspects related to respective disciplines, included the caution to not overlook the potential for significant internal distinctions (Becher, 1994). For the two kinds of social science groupings identified, the pure social sciences domain had a tendency towards individualised work, with a weak linkage to subject-based interest groups outside. In contrast, applied social sciences activity had a strong connection with professional practioners’ associations, which also tended to have a strong influence on curricula and set the agenda for research. This group was thus particularly vulnerable to external pressure.

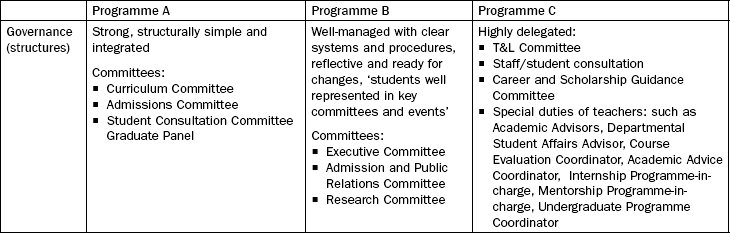

The descriptors in Table 5.2a are summative comments from dialogic communications, typically programme reviews or SEQ-based consultations. Mapped across several categories of feedback, these characteristics demonstrate internal distinctions that may or may not correlate with the earlier noted disciplinary groupings, but in general appear to support Becher’s (1994) concern that macro-level enquiries can conceal or overlook significant internal distinctions. Governance structures, which are central to sustaining the process of feedback and consequent programme enhancement, are highlighted in Table 5.2b.

In summary, Programme A, an applied social science programme, was a highly-rated programme that was reported as proactive in its approach, and with career preparation, described as empowering and practical, as key features. The programme had a coherent curriculum supported by strong staff-student communications. Part of the strength of the curriculum design was in the training and encouragement students got to write papers for publication and for presentations at conferences. Programme B, another applied social science programme, was also strongly rated and described as student-oriented and integrative in its approach. Its key attributes included critical thinking and problem solving that left students more confident in taking up future challenges. Unique features of the programme were the inclusion of discussion and debates organised to enhance students’ knowledge and evaluative skills. Programme C, a humanities or pure social science programme, was an individualistic and loosely-structured programme, reported as lacking focus in key areas of the curriculum. This programme, however, was described as very responsive to feedback, taking remedial action on time.

Response to student feedback

For the notionally more successful programmes (Programme A and Programme B), students’ appreciation and general progress, evidenced by positive reflections on their learning experience, can be readily traced in the feedback and in the supporting data. In terms of how feedback was perceived and used in the selected three programmes, it appears that all programmes actively called for ideas and had regular meetings with faculty members, as well as current students and alumni. These formal meetings were used to collect feedback before programmes set about drafting annual self-evaluation or action plans. Programmes A and B, however, were relatively more active in the use of informal communications, by way of online forums and lunch gatherings that were further encouraged by close teacher-student relationships.

Overall, a notable aspect was the very high expectations Programme A had of its students. Part of this attitude was evident in the willingness to invite feedback on curricular matters, as well on the quality of teaching assistants, academic progress and career planning. Students, characterised as reflective and high achieving, reciprocate, providing high-quality feedback that in turn helps to improve the programme in many ways. Another interesting lesson, drawn from Programme B’s experience, is the need to make examples of curricular improvement more immediately visible. This aspect of responsiveness, which reinforces the collaborative nature of feedback, is perhaps an under-expressed attribute of dialogic feedback. Overall, a common concern for all three programmes is the academic advisory system intended to strengthen teacher-student communications. However, it is evident that many students prefer to seek help from peers or teaching assistants rather than their assigned advisor. The implicit suggestion is that informal channels of communication are worthy of exploration in parallel to formal advisory systems, in order to provide timely and much needed individual guidance.

Based on the respective nature of programme disciplinary knowledge, faculty members appeared to have identified unique issues or key learning outcomes in the curriculum for improvement or attention. These unique issues are integration for Programme A, critical thinking for Programme B, and modelling for Programme C. A common factor across all programmes is employability, a primary concern for HK students. However, it appears that only one programme, Programme A, has taken the initiative in this matter, going beyond simply providing career preparation or guidance to students. As a programme review tabled at the SCTL noted, this programme has proactively: ‘identified a need to meet the gap between the more academic parts … and helping students prepare for finding jobs’. The programme seems to have achieved beyond the programme review recommendation of providing ‘career advice’. An example of Programme A and B’s responsiveness to feedback and care can be seen in the remedial actions planned. Another example, of responsiveness, is in the quality of the response to student concerns as shown in Table 5.2 above, while a tangible example of care is the number and frequency of channels open for students to voice opinions.

Key features and future actions

In summary, some key features and necessary future actions related to feedback are outlined in Table 5.3 below. While there is an abundance of literature on course-level feedback and on what is fed back to the instructor (Brinko, 1991), this chapter has focused on programme-level evaluation and feedback, highlighting the process by which feedback on the programme is received and then acted upon. Assuming feedback as a general communication process, essential aspects of the process can be summarised by asking a series of questions as follows: what (types of feedback); how (is it gathered); when (is it gathered); and (for) whom (Table 5.3 below). There are also some challenges facing this process that suggest future actions by the institution.

Table 5.3

Challenges facing institutional feedback process

| Feedback | Evidence of process |

| What | Diagnostic and dialogic feedback |

| How | Formal: SEQ/GCQ and AQ, as well as internal to programme surveys; feedback mediated by T&L staff Informal: student/alumni consultative committees, online forum and face-to-face meetings |

| When | Annual for formal: ongoing for informal means Necessary extension: boost informal means for ongoing reciprocal feedback |

| Whom | Programme directors and key staff Necessary extension: engage all academic staff and students in a collaborative approach; sharing across disciplines in order to activate learning |

| Challenges | Resources: time and over reliance on university T&L staff Giving and receiving feedback: noting the cultural setting (HK) and cultural issues such as face, there is an added complexity to the giving and receiving of feedback. The setting needs to be safe; feedback needs to be seen as constructive and programme enhancing; but most of all it needs to be shared in a collegial relationship. This involves time and the prior building of relationship networks (guanxi). It also requires judgment, with feedback balanced according to staff developmental levels. Competing agendas: research and teaching; disciplinary cultures Staff development: to build T&L understanding, or else pedagogical issues related to course design and assessment and the wider environment may not be understood. Culture: to foster a culture of learning enhancement there is a need for effective peer networks and relationships, which will require time and constancy in staff appointments. |

Noting the example of the three social science programmes, it is clear that feedback and the ‘diagnostic power’ of the SEQ play out quite differently in the curriculum and in T&L related actions. The central challenge is the resource intensive nature of the process with an over-reliance on T&L staff. This issue may also be reflective of a formative stage in QA development, which may evolve into a distributed and less time-intensive process with greater confidence and T&L understanding. The less obvious, but nonetheless fundamental, aspect of the feedback process is cultural. As noted by Thomas et al. (2011), ‘face’ (mianzi) is an abstract and intangible feature of Chinese social psychology that is crucial in social and interpersonal relationships. This feature requires a good deal of sensitivity and judgment in sharing evaluative feedback. The key facilitative attribute is the ‘relationship’ that is developed over time.

Reflections on practice

This chapter has outlined an evidence-based approach by an institution to improving teaching quality. As outlined, the student experience captured via diagnostic surveys and discussed with programme staff and students via dialogic communication process is a time and labour intensive one. Given the local sensitivities and the scale of recent education reforms in HK, this process can be justified as necessary in order to shift cultural reservations and potential defensiveness from programmes. Perhaps a less appreciated, albeit very necessary, part of effective feedback and one that underpins the sustainability of this institution-wide QA process is a strong peer network and positive guanxi-based relationships.

This study illustrates an institutional approach that started from formative QA and has evolved to substantive QE. Consistent with QE, the CUHK approach to evaluation and feedback tends to be formative in nature and intended to support continual improvement. This approach has brought benefits in terms of student satisfaction and improved learning outcomes. Particular points to be highlighted in terms of the university’s approach include: multi-layered sources of feedback, both diagnostic and dialogic; conveyed by a variety of inter-connected modes; supported by a regular (annual) and active process of consultative activity by academics from the T&L unit, shaped by the quality of relationship with programme managers. A commitment to programme-level confidentiality has been a key facilitator for academic engagement, which has also been helped by the capacity to respond to requests for curricular or general T&L advice, and the capacity to source feedback rapidly via focus groups. Collecting descriptive rather than evaluative data has been well received by programme coordinators.

This chapter has illustrated diversity in practice within the three social science programmes, which suggests the potential for disciplinary characteristics to influence responses to feedback and the wider QE intentions. This in turn suggests policy discussions should seek to reveal and adapt to what can be significant internal distinctions. More broadly, creating a culture of ‘enhancement’, as characterised by Swinglehurst (2008), requires a focus on how students learn and on learning as ‘social practice’ that can be achieved by increasing the level of collaboration between teachers and students, within programmes and between teachers across disciplines. However, the future challenge is to create a quality culture that incorporates all the principles of QE and related feedback processes and applies them in a consistent manner, without the top-down overlay of institutional monitoring.

References

Becher, T. The Significance of Disciplinary Differences. Studies in Higher Education. 1994; 19(2):151–161.

Blackmur, D. Does the Emperor Have the Right (or Any) Clothes? The Public Regulation of Higher Education Qualities over the Last Two Decades. Quality in Higher Education. 2010; 16(1):67–69.

Brinko, K. T. The Practice of Giving Feedback to Improve Teaching. Journal of Higher Education. 1991; 64(5):574–593.

Brookes, M., Becket, N. ‘Quality. Management in Higher Education: a Review of International Issues and Practice’, International Journal of Quality and Standards Paper 3. 2007; 1(1):85–121.

CUHK. Institutional Submission to the Quality Assurance Council, University Grants Committee. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong; 2008.

Harvey, L. The End of Quality? Quality in Higher Education. 2002; 8(1):5–22.

Harvey, L., Williams, J. Fifteen Years of Quality in Higher Education. Quality in Higher Education. 2010; 16(1):3–35.

Ho, D. The Concept of “Face” in the Chinese-American Interaction. In: Hu W., Grove C. L., eds. Encountering the Chinese: A Guide for Americans. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press; 1991:111–124.

Kam, C. C. -S., Bond, M. H. Role of Emotions and Behavioural Responses in Mediating the Impact of Face Loss on Relationship Deterioration: Are Chinese More Face sensitive than Americans? Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2008; 11:175–184.

Kember, D., Leung, Y. P. The Influence of the Learning and Teaching Environment on the Development of Generic Capabilities Needed for a Knowledge-based Society. Learning Environments Research. 2005; 8:245–266.

Kennedy, P. Learning Cultures and Learning Styles: Myth-understandings about Adult (Hong Kong) Chinese Learners. International Journal of Lifelong Education. 2002; 21(5):430–445.

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D., Ko, D., Taylor, S. E. Pursuit of Comfort and Pursuit of Harmony: Culture, Relationships, and Social Support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006; 32:1595–1607.

Luo, Y., Shenkar, O., Nyaw, M. -K. Mitigating Liabilities of Foreignness: Defensive versus Offensive Approaches. Journal of International Management. 2002; 8:283–300.

McKay, J., Kember, D. Quality Assurance Systems and Educational Development. Part 1: The Limitations of Quality control. Quality Assurance in Education. 1999; 7(1):25–29.

Nicol, D. J., MacFarlane-Dick, D. Formative Assessment and Self-regulated Learning: a Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice. Studies in Higher Education. 2006; 31(2):199–218.

Orrell, J. Feedback on Learning Achievement: Rhetoric and Reality. Teaching in Higher Education. 2006; 11:441–456.

QAA. Code of Practice for the Assurance of Academic Quality and Standards in Higher Education. available from http://www. qaa. ac. uk/assuringstandardsandquality/code-of-practice/Pages/default. aspx, 2004. [[accessed 20 September 2012]].

Schein, E. The Leader of the Future. working paper 3832 July 1995, available from http://dspace. mit. edu/bitstream/handle/1721. 1/2582/SWP-3832-33296494. pdf, 1995. [[accessed 20 September 2012]].

Swinglehurst, D., Russell, J., Greenhalgh, T. Peer Observation of Teaching in the Online Environment: an Action Research Approach. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 2008; 24:383–393.

Tam, M. Measuring Quality and Performance in Higher Education. Quality in Higher Education. 2001; 7(1):47–54.

Thomas, K., McNaught, C., Wong, K. C., Li, Y. C. Early-career Academics’ Perceptions of Learning and Teaching in Hong Kong: Implications for Professional Development. International Journal for Academic Development. 2011; 16(3):255–266.

Wiklund, H., Wiklund, B., Edvardsson, B. Innovation and TQM in Swedish Higher Education Institutions – Possibilities and Pitfalls. TQM Magazine. 2003; 15(2):99–107.

Yorke, M. Formative Assessment in Higher Education: Moves towards Theory and the Enhancement of Pedagogic Practice. Higher Education. 2003; 45:477–501.