8

Political Economy of International Trade

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After going through this chapter, you should be able to:

Examine the rationale behind different forms of trade protection

Explain the various forms of trade regulation

Distinguish between tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade

Appreciate the relevance of the changing trade situation for the international business manager

Understand the institutional framework of the multilateral trade environment as well as the direction of foreign trade in India

Examine the different avenues of export promotion in the Indian context

Solar Cells in Fujairah

Anjan Turlapati, CEO of Microsol International, a green-technology company, moved his solar cell manufacturing plant from India to Fujairah in the United Arab Emirates. He made this move because he considered Fujairah a better location, since it is in a thriving free trade zone (FTZ). Located next to the Port of Fujairah, the free trade zone is akin to several other similar sectors found in Dubai, including the region's oldest and largest sector, Jebel Ali Port. Fujairah's free trade zone has benefited from a growing petrochemical industry as well as the bustling port that is one of the world's largest bunkering facilities and a hub for fuel storage. In December 2010, the government of the United Arab Emirates decided to allocate USD 1 billion from its federal budget to help build 35 development projects in Fujairah over the next three years.

Turlapati considers the lack of bureaucracy, simplicity of doing business and lower costs the biggest benefits of operating in Fujairah. On the flip side, it has meant losing local access to scientific research and other resources more easily found in India.

Based in the United Arab Emirates since mid-2003, the company has had a full-fledged manufacturing facility for solar cell manufacture—the only one in the Middle East. It undertakes all the processes involved in the making of a solar cell from chemical processing, diffusion furnaces, and plasma etchers to laser-cutting tools and high-temperature furnaces.

The decision to locate in Fujairah was driven by the desire to be independent, the infrastructure (for example, the shell-like buildings), and the proactive attitude of the authorities. The availability of low-cost skilled labour in Fujairah was another overriding factor in favour of the location. The FTZ also has only one regulatory body to be dealt with, which saves both costs and time. The system also has faith in the individual insight of the businessperson and lets them chart their own course with minimal interaction with the regulatory authorities. As an example, consignments for countries such as Germany, Spain, Portugal, the Czech Republic, China and France do not need to be verified and cleared at the port—the FTZ accepts airline documentation. However, gaps in legal provisions are a matter of concern, as are the lack of research facilities found more easily in India. The easy availability of cutting-edge research including equipment and facilities is lacking, although proximity to Indian shores makes up for a part of the problem.

Source: Information from Anjan Turlapati, “Microsol's Anjan Turlapati on the UAE's Free Trade Zones: ‘The Big Bright Point Is the Lack of Bureaucracy’”, interview by The Wharton School, Arabic Knowledge@Wharton, 11 January 2011, available at http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/arabic/article.cfm?articleid=2603, last accessed on 20 January 2010.

INTRODUCTION

The current phase of globalization starting in the aftermath of World War II, strongly bolstered by new communications and transport technologies, has been marked by a prolonged period of strong trade and economic growth.

The discussion of trade theory in Chapter 7 examines the theoretical basis of international trade and the gains to the world economy through its free and fair existence. In actual fact, it is seen that all countries interfere with international trade to varying degrees. Government intervention takes place to achieve different economic, political or social objectives. This chapter examines the different rationales for protection adopted by nations and then looks at the different forms that protection can take. It then looks at the institutional framework governing global trade and the direction of foreign trade in India and examines the different measures taken by the government to promote exports in India.

GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION IN TRADE

There are two rationales for government intervention in trade—an economic rationale and a non-economic rationale.

Economic Rationale

The reasons for adopting an economic rationale are the protection of domestic industries, employment generation and industrialization of the domestic economy, and improving the balance of payments position.

Protection to Infant and Domestic Industry

The infant industry argument proposed in 1792 by Alexander Hamilton is the oldest economic reason for trade intervention. The use of protection in the interest of domestic industries is the most common reason for its use. The proponents of this argument posit that though an industry acquires competitive advantage in the long run, it requires protection in the initial stages of its life. This is a period when the firm secures finance, gains mastery over production techniques, trains its labour force, and begins to reap economies of scale. It is argued that in the absence of these measures, it is impossible for the domestic firm to face competition in low-priced goods. This argument was the basis for protection and an inward-looking Indian industrial policy in the initial stages of the development of its industries, as was the case for several other developing countries. The argument is acceptable under the provisions within the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) as well and has been a defining characteristic of international trade for the last 50 years. It has been seen, however, that protection only helped to foster inefficiency as protected industries rarely made the effort to adopt efficient methods of production due to the security they received in a protected environment.

Employment and Industrialization

This is a corollary of the infant industry argument which emphasizes the employment and industrialization benefits to the domestic economy as a result of setting up domestic manufacturing. This, in turn, leads to regional and national growth. A frequently used argument against free trade is that trade should benefit the interests of the domestic citizens first. In the aftermath of the recent global crisis of 2008, there was a large-scale move in the United States to “buy American goods” in the interest of the domestic economy. A commonly used argument against export that originates in low-cost foreign countries is that it threatens the domestic worker who works at a higher wage rate. The argument fails to take note of the fact that the decision to export is based on total costs, of which the wage rate may often be an insignificant component. Taking into account the higher productivity in developed domestic markets due to the use of more and better capital, superior management, and advanced technology, the total labour cost component of goods is lower even though the total cost is higher.

Balance of Payments Position

Persistent deficits in a country's balance of payments often force countries to resort to trade restrictions. For example, countries such as India find themselves burdened with the import of oil and related products. This often leads countries to promote policies such as tied imports, that is, imports which will help in re-export to help its balance of payments position. Although protection is meant to be temporary, in reality, it extends over a long time period, as a firm or industry rarely ever admits that it is not required.

Non-economic Rationale

The reasons for adopting a non-economic rationale are discussed in this section.

Preservation of National Identity and Culture

It has been argued that free trade is a threat to national identity, culture, and institutions. It is on these grounds that countries impose restrictions on foreign media, which is perceived to be a major source of access to foreign culture. Countries such as Canada and France impose restrictions on foreign media as they consider it a threat to their language and culture. Japan, on the other hand, imposes a high tariff on rice, which is essential to their way of life.

Trade as a Bargaining Tool

Trade protection is often used as a tool to bargain with trading partners as countries often use the reciprocity argument for imposing trade barriers. This could take the form of passive reciprocity, where a country refuses to lower or eliminate its barriers to trade until the other party does the same. On the other hand, active or aggressive reciprocity takes the form of threats where a country may withdraw previous concessions or threaten to take retaliatory steps if the other party does not respond with similar concessions. For instance, the US government threatened China with stringent trade sanctions to try and get the Chinese to improve their intellectual property laws, which were causing US companies such as Microsoft to lose billions of dollars in trade revenue. The use of trade protection as a bargaining tool can be a double-edged sword, which can lead to trade openness and its attendant benefits if it is successful, but could severely restrict trade if the partner country retaliates through similar measures of protectionism.

Protection of Consumer and Human Rights

Trade restrictions are often meant to protect domestic consumers against products that are unsafe and hazardous. The European Union (EU), for instance, has strict guidelines and even imposes barriers against agricultural produce entering its markets. This includes the sale of hormone-treated meats and produce from genetically modified crops. Countries such as the United States have also resorted to measures like not granting the most-favoured-nation (MFN) status to China to protest against its human rights violations.

INSTRUMENTS OF TRADE CONTROL

Government intervention in trade takes the form of tariff and non-tariff barriers. Tariff barriers are direct official constraints on the import of certain goods and services that are non-discretionary in application. Non-tariff barriers are indirect measures that discriminate against foreign goods in the domestic market or otherwise distort and constrain trade and have a discretionary application. Tariff barriers affect prices; non-tariff barriers can affect either price or quantity directly.

Tariff Barriers

A tariff (sometimes called duty) is the most common type of trade control and is a tax that governments levy on a good shipped internationally, above and beyond taxes levied on domestic goods and services. Tariffs are transparent and are typically set on an ad valorem basis, that is, on the basis of the value of the good or service in question. Governments charge a tariff on a good when it crosses an official boundary, whether it is that of a country, for example, Mexico, or a group of countries, like the EU, that have agreed to impose a common tariff on goods entering their bloc.

Tariff barriers are direct official constraints on the import of certain goods and services that are non-discretionary in application.

Tariffs collected by the exporting country are called export tariffs; if collected by a country through which the goods have passed, it is called a transit tariff; and if collected by the importing country, it is called an import tariff. The import tariff is by far the most common. A government may also assess a tariff on a per-unit basis, in which case, it is applying a specific duty. A tariff assessed as a percentage of the value of the item is an ad valorem duty. Lastly, a tariff assessed as both a specific duty and an ad valorem duty on the same product, is a compound duty. A specific duty is straightforward for customs officials who collect duties, because they do not need to determine a good's value on which to calculate a percentage tax.

Figure 8.1 illustrates how tariff and non-tariff barriers affect both the price and the quantity sold, although in a different order and with a different impact on producers. Both parts (a) and (b) of Figure 8.1 have downward-sloping demand curves (D) and upward-sloping supply curves (S). In other words, the lower the price, the higher the quantity that consumers demand; the higher the price, the more that suppliers make available for sale. The intersection of the S and D curves illustrates the equilibrium price (P1) and quantity sold (Q1), determined by market forces without government interference.

Figure 8.1 (a) shows the impact of the imposition of a tariff on price and quantity in the market. A tariff acts like a tax and raises the price of the commodity in the market from P1 to P2. As a consequence, the amount consumers are willing to buy will fall from Q1 to Q2. The price rise does not benefit the producers since it goes to the government as taxes rather than profits.

Figure 8.1 (b) shows the impact of a non-tariff barrier on price and quantity. A non-tariff barrier acts as a restriction on supply, giving rise to a new supply curve (S1). The quantity sold now falls from Q1 to Q2. At the lower supply, the price rises from P1 to P2, as equilibrium is attained at a new point due to the interaction of the D and S1 curves.

Figure 8.1 Impact of Tariff and Non-tariff Barriers on Price and Quantity

The major difference in the two forms of trade control is that sellers raise the price in part (b), which helps compensate them for the decline in quantity sold. In part (a), producers sell less and are unable to raise their price because the tax has already done it.

Import tariffs raise the price of imported goods, thereby giving domestically produced goods a relative price advantage. A tariff may be protective even though there is no domestic production in direct competition. For example, a country that wants its residents to spend less on foreign goods and services may raise the price of some foreign products, even though there are no close domestic substitutes in order to curtail demand for imports.

Tariffs also serve as a source of government revenue. Generally, import tariffs are of little importance to industrial countries; for example, the EU spends about the same to collect duties as the amount it collects. Tariffs, however, are a major source of revenue in many developing countries. This is because government authorities in developing countries have more control over determining the amounts and types of goods crossing their borders and collecting a tax on them than they do over determining and collecting individual and corporate income taxes. Although revenue tariffs are most commonly collected on imports, many countries that export raw materials charge export tariffs. Transit tariffs were once a major source of revenue for countries, but government treaties have nearly abolished them.

There is often a tariff controversy concerning industrial countries’ treatment of manufactured exports from developing countries that seek to add manufactured value to their exports of raw materials (like making tea bags from tea leaves). Raw materials frequently enter industrial countries free of duty; however, if processed, they are assigned an import tariff. Since an ad valorem tariff is based on the total value of the product encompassing the raw materials and the processing combined, developing countries argue that the effective tariff on the manufactured portion turns out to be higher than the published tariff rate. For example, a country may charge no duty on tea leaves but may assess a 10 per cent ad valorem tariff on instant tea. If INR 50 for a package of instant tea bags covers INR 25 in tea leaves and INR 25 in processing costs, the duty is effectively on the manufactured portion, because the tea leaves could have entered duty-free. This anomaly further challenges developing countries to find markets for their manufactured products. At the same time, the governments of industrial countries cannot easily remove barriers to imports of developing countries’ manufactured products largely because these imports affect unskilled or unemployed workers who are least equipped to move to new jobs.

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS IN ACTION | Banana Wars

Jamaican lawmakers have geared up to fight a WTO proposal to be implemented by the EU to reduce import tariffs on bananas from EUR 176 per tonne to EUR 116 per tonne by the year 2015. The move is being implemented by the EU under pressure from Ecuador and the United States. In fact, even the earlier price of EUR 176 was a compromise implemented in 2006, which Ecuador subsequently complained was anti-competitive.

The countries in the 77-nation African, Caribbean and Pacific Group (ACP) have said that the new EUR 116 per tonne proposal would make the situation worse for small producing nations already struggling to survive the erasure of preferential prices to its main EU market and the competition from cheaper producers in the Latin American region. Their bananas largely enter the EU duty-free.

Bananas have been a bone of contention at the WTO since 1999, in a ruling which held the EU responsible for violation of international trade law by establishing quotas and tariffs on bananas from Latin America imported by US-based Chiquita Brands International, Dole Foods and Fresh Del Monte Produce. At the same time, the EU allowed licensed access for bananas from former colonies in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, creating trade opportunities worth USD 191 million for the United States.

Jamaica, the largest island in the Caribbean, has a long history of banana production with commercial exports commencing in 1900, providing between 5 per cent and 10 per cent of total employment on account of being labour intensive and ranking second only to sugar in economic significance, making a valuable contribution to foreign exchange earnings.

The banana business is hardly lucrative, witnessing a fall in sales and prices over the years. With tricky transportation and the susceptibility of the crop to disease, the cultivators hardly benefit and major profits are pocketed by firms with import licenses.

According to the affected nations, the proposal to reduce import tariffs on bananas further is likely to seriously compromise the competitiveness of bananas from Jamaica and the rest of the Caribbean in the EU market. The Latin American producers, who are said to control more than 80 per cent of the EU market, and whose banana industry has significant ownership by US-based corporations, have mostly been the ones to win these banana wars. However, the announcement of the EU decision to cut banana tariffs again has been followed by indications that the affected parties (especially Jamaica) are prepared to be disagreeable.

Source: Information from Lavern Clarke, “Banana Issue Threatening to Split WTO”, Jamaica Gleaner News, 25 July 2008, available at http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20080725/business/business8.html, last accessed on 24 January 2011.

Non-tariff Barriers

There are two kinds of non-tariff barriers, namely, direct price influences and quantity controls.

Non-tariff barriers are indirect measures that discriminate against foreign goods in the domestic market or otherwise distort and constrain trade and have a discretionary application.

Direct Price Influences

The principal forms of direct price influences are subsidies and aids and loans.

Subsidies Direct payments made by the government to domestic companies to encourage exports or to protect them from imports are known as subsidies. They can take the form of cash payments, government participation in ownership, low-cost loans to foreign buyers and exporters, and preferential tax treatment. Governments may offer potential exporters many business development services, such as market information, trade expositions, and foreign contacts. From the standpoint of market efficiency, subsidies are more justifiable than tariffs because they seek to overcome, rather than create, market imperfections. There are also benefits to disseminating information widely because governments can spread the costs of collecting information among many users.

Aid and loans Governments also give aid and loans to other countries. The assistance is known as tied loans if the funds are for a specific use. Tied aid helps win large contracts for infrastructure, such as telecommunications, railways, and electric-power projects. However, there is growing scepticism about the value of tied aid. Tied aid can slow the development of local suppliers in developing countries, and it can shield suppliers in the donor countries from competition.

Countries also use other means to affect prices, including special fees (such as for consular and customs clearance and documentation), requirements that customs deposits be placed in advance of shipment, and minimum price levels at which goods can be sold after they have customs clearance.

Quantity Controls

Governments use other non-tariff regulations and practices to directly affect the quantity of imports and exports. Principal forms of quantity controls include the following:

Quotas The quota is the most common type of quantitative import or export restriction, which prohibits or limits the quantity of a product that can be imported or exported in a given year. An import quota prohibits or limits the quantity of a product that can be imported in a given year and an export quota prohibits or limits the quantity of a product that can be exported in a given year. Quotas raise prices just as tariffs do but, since they are defined in physical terms, they directly affect the amount of imports by putting an absolute limit on supply, for example, three million DVD players from a particular country in a given year. Therefore, quotas usually increase the consumer price because there is little incentive to use price competition to increase sales. A notable difference between tariffs and quotas is their direct effect on revenues. Tariffs generate revenue for the government. Quotas generate revenues for those companies which are able to obtain a portion of the limited supply of the product by selling it in the domestic market.

A country may establish export quotas to assure domestic consumers of a sufficient supply of goods at a low price, to prevent depletion of natural resources, or to attempt to raise export processes by restricting supply in foreign markets. To restrict supply, some countries band together in various commodity agreements, such as those for coffee and petroleum, which then restrict and regulate exports from the member countries. The typical goal of an export quota is to raise prices for importing countries.

Sometimes, governments allocate quotas among countries based on political or market conditions. This choice can create problems because goods from one country might be trans-shipped or deflected to another country to take advantage of the latter's unused quota. Prior to the ending of the Multi Fibre Arrangement (MFA) in 2004, this method was used to bring in USD 2 billion in illegal clothing imports from China to the United States annually.

Sometimes, goods are subject to tariff rate quotas, according to which, a certain quantity of goods enter the country duty-free or at a low rate. However, there is a very high duty for subsequent imports. For example, since January 2006, the EU allows tariff-free imports of 775,000 tonnes of bananas annually from the Caribbean and African countries, but beyond that limit, all imports are subject to a duty of EUR 176 per tonne. Since the EU imports bananas from Central and South America as well, the tariff effectively subsidizes the banana export from the African and Caribbean nations and penalizes the producers from Central and South America.

Voluntary export restraints A voluntary export restraint (VER) is a generic term used to describe all bilateral agreements that restrict exports. It is voluntary because a country has a formal right to eliminate or modify it at any time. For example, in the 1980s, the United States convinced the Japanese government to “voluntarily” limit their exports of automobiles to the United States to no more than 1.85 million vehicles per year. Therefore, like a quota, a VER limits the quantity of trade between countries and, therefore, raises the prices of imported goods to consumers. It was estimated by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) that US consumers overpaid nearly USD 5 billion for Japanese automobiles between 1981 and 1985 due to the automobile industry VER. Procedurally, VERs have unique advantages. A VER is much easier to switch off than an import quota. In addition, the appearance of a “voluntary” choice by a particular country to constrain its exports to another country does less political damage to the participating countries than an import quota does.

Orderly marketing arrangements This is a kind of VER consisting of formal agreements between governments to restrict international competition and keep a part of the domestic market for local producers. The MFA, which began in 1973 and regulated about 80 per cent of the world market in textiles and apparel exports, is an example of this. However, under the provisions of the 1994 GATT negotiations, all textile quotas under the MFA expired on 1 January 2005.

Embargoes An embargo is a specific quota that prohibits all forms of trade. Countries or groups of countries may place embargoes on either imports or exports, on entire categories of products regardless of destination, on specific products to specific countries, or on all products to given countries. Governments often impose embargoes in an attempt to use economic means to achieve political goals.

“Buy local” legislation Another form of quantitative trade control is the “buy local” legislation. Very often, government purchases, which form a large part of total national expenditures, are from domestic producers only. In the United States, for example, “buy American” legislation requires government procurement agencies to favour domestic goods. Sometimes, governments specify a domestic content restriction, that is, a certain percentage of the product must be of local origin. Sometimes, they favour domestic producers by establishing floor-price mechanisms for competing foreign goods. For example, a government agency may buy a foreign-made product only if the price is at some predetermined margin below that of a domestic competitor. Many countries prescribe a minimum percentage of domestic content that a given product must have for it to be sold legally in their country.

Testing standards Countries often have various classifications, labelling, and testing standards to protect the health and safety of its citizens. For exporting firms, however, these are a source of complex and discriminatory barriers to free trade. The purpose of these is often to promote the sale of domestic products and complicate the sales of foreign products. An example of these is product labels, which need to indicate their source of manufacture. This adds to the firm's production cost, since it may also need to be translated into different languages for different markets. Further, since raw materials, components, design, and labour increasingly come from various countries, most products today are of mixed origin. For example, provisions in the United States stipulate that any cloth substantially altered (for instance, woven) in another country must identify that country on its label. Consequently, designers like Ferragamo, Gucci, and Versace must declare “made in China” on the label of garments that contain silk from China.

The professed purpose of testing standards is to protect the safety or health of the domestic population. However, some foreign companies argue that testing standards are just another means to protect domestic producers. For example, EU standards keep some US and Canadian products out of the European market completely. This is the case with genetically engineered corn and canola oil even though the worldwide scientific community reports that genetic engineering poses no human health risk and France itself grows and sells a small amount of genetically engineered corn. Kellogg's needs to make four different kinds of corn flakes because different nations have different standards about the vitamins which need to be added to enrich it.1 Japan similarly prohibits the import of creamy mustard, light mayonnaise, and figs which contain potassium sorbate, a food additive allowed by it in various other products that are of Japanese origin. Canadian regulations similarly treat calcium-enriched orange juice as drugs which have special production and marketing requirements.2

Specific permission requirements The requirement to obtain permission from government authorities in order to conduct trade transactions is known as a licence. Procedures for this vary between countries and sometimes require the firm to submit samples to the authorities. This procedure can restrict imports or exports directly by denying permission and indirectly because of the cost, time, and uncertainty involved in the process. Foreign-exchange controls similarly limit the availability of foreign exchange for trade and investment. It requires an importer of a given product to apply to a government agency to secure the foreign currency to pay for the product. As with an import license, failure to grant the exchange, not to mention the time and expense of completing forms and awaiting replies, obstructs foreign trade.

Administrative delays Government policies such as customs rules often discriminate against trade practices. These are intentional administrative delays such as the Chinese requirement of different rates of duty for different products depending on the port of entry and an arbitrary determination of the value of goods.3 Other examples are the requirement of the Australian government that all television commercials be shot in the country itself even for foreign media companies.

Reciprocal requirements or countertrade The exchange of merchandise for other goods or services is called an offset or countertrade transaction. Governments sometimes require exporters to take actual merchandise in lieu of money or to promise to buy merchandise or services in place of cash payment in the country to which they export. This requirement is common in the aerospace and defence industries, sometimes because the importer does not have enough foreign currency. For example, Russia's commercial airline, Aeroflot, has exchanged Russian crude oil for Airbus aircraft. More frequently, however, reciprocal requirements are made between countries with ample access to foreign currency that want to secure jobs or technology as part of the transaction. For example, McDonnell Douglas Corporation sold helicopters to the British government but had to equip them with Rolls-Royce engines (made in the United Kingdom) as well as transfer much of the technology and production work to the United Kingdom. These sorts of barter transactions are called countertrade or offsets.

REGION FOCUS | Brazilian Beef Exports

Brazil has been a major beef exporter since 2004, producing almost 7 million metric tons of beef each year from a total population of 165 million head. Its exports have tripled from 2008 to 2010 to about 550,000 tonnes reaching diverse destinations, such as Chile, Egypt, Germany, Iran, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, the EU, and the United States.

Today, exporters around the world, including Brazil, face numerous non-tariff requirements (for example, sanitary requirements, technical requirements, etc.) on agricultural products. These requirements are particularly challenging for developing countries, which often lack the specialized human capital, technological support and institutional infrastructure, and financial capital to assess and comply with these regulations.

The Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) agreements, drafted by the World Trade Organization (WTO), require member countries to follow international scientific and technical guidelines to maintain quality standards and meet sanitary and technical requirements. These agreements also recognize the equivalence of regulations across nations. This has a bearing on the highly regulated and protected international meat market, in particular, the bovine meat product, which forms a substantial share of this market.

The diverse requirements of importers has made exporting products a costly and difficult exercise, considering the complexity of harmonization and equivalence processes of WTO policies. Moreover, in some cases (for example, Brazil), the insistence that sanitary and technical requirements have not been met has raised suspicion that these policies are being used to restrict commerce instead of focusing on health and safety issues.

A common problem facing Brazilian beef exporters is coping with private standards (those imposed by importing companies) which generate more difficulties and higher compliance costs than government rules. It has also emerged that Brazilian exporters are often not well-informed about the international regulatory environment concerning trade in beef. Taking into account all these factors, it is important to develop a system for monitoring and evaluating the various non-tariff measures imposed by importers and for sharing this information among the public and the private sector. The monitoring system would help to determine whether the non-tariff measures are legitimate under WTO provisions and to assess the social, environmental, and economic impacts of these measures. It would also help in analysing the possibility of political negotiations with importing countries.

There is a need in Brazil to develop databases on non-tariff measures to educate exporters about the international beef market and its regulations. Information dissemination on sanitary and technical requirements, and data on past or present trade disputes between companies and between countries would be a rich source of data for further analyses. Closer relationships between government agencies, research institutes, and universities would also help to facilitate the exchange of information and data. The government also has a big role to play by providing technological support and infrastructure in helping Brazilian exporters conform to international regulatory standards.

Increased participation by Brazil and other developing countries at international forums that address sanitary and technical regulation and standardization, such as Codex Alimentarius, World Organization for Animal Health, and International Plant Protection Convention, would give these developing nations a larger perspective on these issues. The current low level of participation by developing countries means that the sanitary and technical guidelines are driven largely by the interests of the developed countries. In order to change this situation, developing countries need to invest in education and technological infrastructure, and in its human capital. Assistance from countries that have abundant human and financial resources can also help developing countries to effectively deal with sanitary and technical issues.

Source: Information from Sílvia Helena Galvāo de Miranda and Geraldo Sant'Ana de Camargo Barros, “Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade in Agricultural Products: Challenges for Brazil's Beef Exports”, Policy Brief, International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium (IATRC), Policy Brief #PB2010-04, 5 June 2010, available at http://iatrc.software.umn.edu/publications/policybriefs/PB2010-04%20deMiranda.pdf, last accessed on 20 January 2011.

Jones Day ranked number one globally in M&A league tables (a tool that measures different aspects of global M&A activity) for year-end 2010, maintaining a position it has held for 41 consecutive quarters since 2000 in the United States. Increasingly active in the Indian market through an associate office, Jones Day has successfully leveraged its traditional capital market strength to handle an increased flow of banking and M&A work. It also advised Atlas Energy on its USD 1.7 billion joint venture with Reliance Industries, the largest private sector company in India.

The entry of the leading US legal firm is indicative of India's potential to become one of the world's great legal centres in the twenty-first century, alongside London and New York. It has innate advantages in its common law traditions and English language capability. However, until very recently, India had not recognized the role that advisory legal services have to play in attracting foreign investment and developing a broader-based services economy.

As a signatory to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which is an organ of the WTO, India is under an obligation to open up its service sector to member nations. The term “services” includes the legal sector in this context. Liberalization of the economy has opened the floodgates to transnational corporations (TNCs) whose business transactions are governed by Indian law and represented by local lawyers. There is also increasing pressure on the Indian government to open up the legal profession to foreign firms under the provisions of GATS and the International Bar Association (IBA).

This would require an amendment of the Advocates Act of 1961, which governs legal practice in India. The term “legal practice” is not defined in the Advocates Act, but a reading of Sections 30 and 33 of the Act indicates that practice is limited to appearance before any court, tribunal or authority. It does not include legal advice, documentation, alternative methods of resolving disputes, and such other services. As per a recent ruling of the Bombay High Court, foreign law companies (FLCs) cannot carry on non-litigious practice in India, which includes drafting of applications, consultancy work, or any legal work that does not involve appearing before the courts, unless they abide by the Advocates Act. As a result, tie-ups with Indian firms continues to be an important strategic consideration for Western law firms, since it offers an opportunity to develop local knowledge and share business opportunities. The better aligned the interests, practice areas, and client bases of the respective firms, the more productive and profitable the tie-up relationship is likely to be. International firms Ashurst, Chadbourne & Parke, and White & Case opened liaison offices in India after the Reserve Bank of India granted them permission under the Foreign Exchange Management Act, with the condition that these firms would not earn any income in India.

The basic principles set out by IBA on the question of validity of FLCs are fairness, uniform and non-discriminatory treatment, clarity and transparency, professional responsibility, reality, and flexibility. It is open to the host authority to impose the requirement of reciprocity and to impose reasonable restrictions on the practice of FLCs in the host country. Opinion on the entry of foreign firms is, however, still cautious, suggesting the need for some restrictions, adequate safeguards, and qualifications, besides the need for reciprocity.

Tradition and practice varies across the world, for instance, many Western nations allow their lawyers to advertise, whereas in India it is considered unethical to do so. In countries like Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan, the FLCs are only permitted to service foreign firms. The United States and some other advanced countries have large law firms akin to large TNCs and are designed to promote the commercial interest of their gigantic client corporations. The size, power, influence, and economic strengths of these giants are such that they would likely be a challenge to the domestic legal system on their entry into India. These firms also offer “single window services” to their clients, which not only include legal services but also accountancy, management, financial, and other advice.

In India, the number of partners in a legal firm is restricted to only 20 as per the provisions of the Partnership Act of 1936. However, the opening up of the legal market, which is an inevitable consequence of the process of globalization, could well translate into an increasing range of job opportunities and consequent growth of the legal profession in the country.

Sources: Information from Ashok Priyadarshi Nayak, “Advent of Foreign Law Firms in India”, Ezine Articles, available at http://ezinearticles.com/?Advent-of-Foreign-Law-Firms-in-India&id=948177, last accessed on 20 January 2011; RSG India Law Centre, “The Ties That Bind”, available at http://rsg-india.com/foreign-law-firms/news/ties-bind, last accessed on 20 January 2011, and Almas Meherally, “Foreign Law Firms Barred from Non-litigious Practice in India”, The Economic Times, 17 December 2009, available at http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/news-by-industry/services/consultancy-/-audit/Foreign-law-firms-barred-from-non-litigious-practice-in-India/articleshow/5345542.cms, last accessed on 20 January 2011.

Restrictions on services Many countries depend on revenue from the foreign sale of such services as transportation, insurance, consulting, and banking. Countries restrict trade in services for three reasons:

- Essentiality: Service industries are considered essential since they have a strategic role in society and because they provide social assistance to their citizens. Countries, therefore, restrict the operation of certain private companies, both foreign and domestic, in sectors such as postal services, education, and health services because they function on a non-profit basis. Services are also restricted in sectors such as media, communications, and banking for foreign companies. In other cases, they set price controls for private competitors or subsidize government-owned service organizations, creating disincentives for foreign private participation. Even when these services are privatized, there is a preference for domestic ownership and control.

- Licensing standards: Governments limit foreign entry into many service professions to ensure the existence of standards of performance. The licensing standards of different professional services vary between countries for professionals such as accountants, actuaries, architects, electricians, engineers, gemologists, hairstylists, lawyers, physicians, real-estate brokers, and teachers. In the absence of reciprocal recognition in licensing between different countries, it is difficult for an accounting or a legal firm from one country to do business in another country, even if there is a manifest need in the domestic country. This needs the use of local professionals within each foreign country or the use of certification where required. The latter option can be difficult because examinations will be in a foreign language and likely emphasize materials different from those in the home country. Further, there may be lengthy prerequisites for taking an examination, such as internships and course work at a local university.

- Immigration requirements: In order to work in a foreign land, professionals need to comply with immigration requirements. Very often, government regulations require that an organization, domestic or foreign, first search extensively for qualified personnel locally before it can apply for work permits for personnel it would like to bring in from abroad. Even if no one from domestic sources of labour is available, hiring a foreigner is still difficult.

INTERNATIONAL TRADE REGULATION

International trade regulation is a recent phenomenon which has its roots in the establishment of multilateral trade organizations such as the GATT and the WTO. The basis of multilateral trade is the principles of non-discrimination, reciprocity, market access, and fair competition, which have been embodied in both the GATT and WTO agreements.

The WTO is a multilateral trade organization that came into existence on 1 January 1995, and is the successor to the GATT, which was created in 1947 and continued to operate for almost five decades as a de facto international organization.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) came into existence in 1947 as an international organization for the facilitation of trade liberalization. The reconstruction of the world economy after World War II witnessed the inception of the Bretton Woods institutions now known as the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These have been explained in detail in Chapter 11. There was a simultaneous move for an international organization to liberalize trade, called the International Trade organization (ITO). The ITO Charter, however, could never be ratified and in its place the GATT, which had been proposed as an interim arrangement, became the de facto international organization for the regulation and liberalization of international trade. Since the original signatory nations expected the agreement to become part of the more permanent ITO Charter, the text of the GATT contains very little institutional structure. This lack of detail within the agreement often created increasing difficulties, as the GATT membership and roles governing trade between the world's nations grew. The GATT functioned as an international organization for many years even though it was never formalized as such. The WTO replaced the GATT as an international organization, but the General Agreement still exists as the WTO's umbrella treaty for trade in goods.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) came into existence in 1947 as an international organization for the facilitation of trade liberalization. Its main objective was the facilitation of international trade through the reduction of tariff barriers, quantitative restrictions, and subsidies on trade.

Objectives and Principles

The GATT was a treaty, not an organization. Its main objective was the facilitation of international trade through the reduction of tariff barriers, quantitative restrictions, and subsidies on trade through a series of agreements. Its main objectives, listed in the preamble are:

- Raising the standard of living

- Ensuring full employment, and a large and steadily growing volume of real income and effective demand

- Developing the full use of the resources of the world

- Expansion of production and international trade

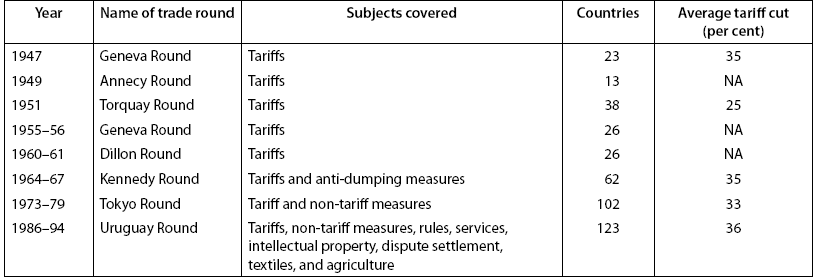

For almost half a century, the GATT's basic legal principles remained much as they were in 1948. There were additions in the form of a section on development in the 1960s and plurilateral agreements (agreements involving fewer members with a specific interest in an issue) with voluntary membership in the 1970s, while efforts to reduce tariffs further continued. Much of this was achieved through a series of multilateral negotiations known as trade rounds. The biggest leaps forward in international trade liberalization have come through these rounds, which were held under the GATT's auspices (see Table 8.1).

The history of the GATT can be divided into three phases. The first phase from 1947 until the Torquay Round, largely concerned which commodities, would be covered by the agreement and freezing existing tariff levels. The second phase, encompassing three rounds, from 1959 to 1979, focused on reducing tariffs. The third phase, consisting only of the Uruguay Round from 1986 to 1994, extended the agreement fully to new areas such as intellectual property, services, capital, and agriculture. Out of this round, the WTO was born.

The early GATT trade rounds only concentrated on reducing tariffs. It was the Kennedy Round in the mid-sixties, which introduced an Anti-dumping Agreement and a section on development. The Tokyo Round during the seventies was the first major attempt to tackle non-tariff trade barriers, and to improve the system. The eighth round, that is, the Uruguay Round of 1986–94, was the last and most extensive round, which led to the establishment of the WTO and a new set of agreements.

Table 8.1 Multilateral Negotiations Under GATT

Source: Reproduced with permission from World Trade Organization, “The GATT Years: From Havana to Marrakesh”, available at http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact4_e.htm, last accessed on 20 January 2011.

Uruguay Round

The last round of multilateral trade negotiation under the GATT, known as the Uruguay Round, started in 1986, but remained largely inconclusive on account of the complexities of the issues involved in it. In December 1990, the then director general Arthur Dunkel presented a draft solution called the Dunkel Draft, which was later replaced by an enlarged agreement. This agreement was finally approved on 15 December 1993.

The Uruguay Round included the following areas for the first time:

- Trade in services leading to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

- Trade-related aspects of intellectual property leading to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs)

- Trade-related investment measures leading to the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs)

Gatt: An Evaluation

Although the GATT was established as a provisional organization with a limited field of action, it had undisputed success in the 47 years of its existence in the promotion and the liberalization of world trade. Continual reductions in tariffs alone helped to increase world trade to high rates of about eight per cent growth during the 1950s and 1960s. The momentum of trade liberalization ensured that trade growth consistently outpaced production growth throughout the GATT era, a measure of the increasing ability of member countries to trade with each other and to reap the benefits of trade. The rush of new members during the Uruguay Round demonstrated that the multilateral trading system was recognized as an anchor for development and an instrument of economic and trade reform.

Problems arose with the passage of time and although the Tokyo Round in the 1970s attempted to tackle some of these, it had limited success.

The GATT's success in reducing tariffs to a very low level, combined with a series of economic recessions in the 1970s and early 1980s, drove governments to look for other forms of protection for domestic sectors, which were threatened by increased foreign competition. High rates of unemployment and the shutting down of factories led governments in Western Europe and North America to seek bilateral market-sharing arrangements with competitors, and to embark on a subsidies race to maintain their hold on agricultural trade. Both these changes undermined the GATT's credibility and effectiveness.

Besides the deteriorating trade-policy environment, by the early 1980s, the GATT was clearly no longer as relevant to the realities of world trade as it had been in the 1940s. There were a number of reasons for this change:

- World trade became far more complex and important than 40 years before with the globalization of the world economy. Trade in services (not covered by the GATT rules) became of major interest to more and more countries, and international investment expanded even more.

- Expansion in merchandise trade matched the expansion of services trade.

- The GATT met with limited success in the realm of agriculture, as loopholes in the multilateral system were heavily exploited, and efforts at liberalizing agricultural trade were largely ineffective.

- In the textiles and clothing sector, an exception to the GATT's normal disciplines was negotiated in the 1960s and early 1970s, leading to the MFA.

- Even the GATT's institutional structure and its dispute settlement system were a cause for concern.

These and other factors convinced GATT members of the need for a renewed effort to reinforce and extend the multilateral system. That effort resulted in the Uruguay Round, the Marrakesh Declaration, and the creation of the WTO.

World Trade Organization

The WTO is a multilateral trade organization aimed at international trade liberalization. It came into existence on 1 January 1995 as the successor to the GATT. At the heart of the system, known as the multilateral trading system, are the WTO's agreements, negotiated and signed by a large majority of the world's trading nations, and ratified in their parliaments. These agreements are the legal ground-rules for international commerce. Essentially, they are contracts guaranteeing member countries important trade rights. They also bind governments to keep their trade policies within agreed limits for everybody's benefit. As of July 2008, the WTO had 153 members.4

The WTO is a multilateral trade organization which aims at international trade liberalization.

As the keeper of the rules of trade between nations at a near-global level, the WTO is responsible for negotiating and implementing new trade agreements, and is in charge of policing member countries’ adherence to all the WTO agreements. Most of the WTO's current work comes from the 1986–94 negotiations called the Uruguay Round, and earlier negotiations under the GATT. The organization is currently the host to new negotiations, under the Doha Development Agenda (DDA) launched in 2001.

The WTO is governed by a Ministerial Conference, which meets every two years; a General Council, which implements the conference's policy decisions and is responsible for day-to-day administration; and a director-general, who is appointed by the Ministerial Conference. The WTO's headquarters are in Geneva, Switzerland.

Principles of WTO

The WTO is governed by certain basic guiding principles which are further embodied in the form of complex agreements covering a wide range of activities. The basic areas they deal with are agriculture, textiles and clothing, banking, telecommunications, government purchases, industrial standards and product safety, food sanitation regulations, intellectual property, etc. These principles are as follows:

Most-favoured-nation status Under the WTO agreements, countries cannot normally discriminate between their trading partners. Granting a special favour, advantage, or privilege to one country (such as a lower customs duty rate for one of their products) means that the same favour has to be granted to all other WTO members. This is known as the most-favoured-nation (MFN) status, which is granted by WTO members to each other.

The MFN treatment is a basic pillar of multilateral trade negotiations and is also the first article of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which governs trade in goods. MFN is also a priority in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). Although in each agreement, the principle is handled slightly differently, together, these three agreements cover all three main areas of trade handled by the WTO.

There are some exceptions which are allowed to the MFN rule. For example, countries can set up a free trade agreement that applies only to goods traded within the group but discriminates against goods from outside. They can also give developing countries special access to their markets or raise barriers against products that are considered to be traded unfairly from specific countries. Limited discrimination is allowed in the area of services too. However, the agreements only permit these exceptions under strict conditions. In general, MFN means that every time a country lowers a trade barrier or opens up a market, it has to do so for the same goods or services from all its trading partners—whether rich or poor, weak or strong.

National treatment This principle implies that imported and locally produced goods should be treated equally once they are in the domestic market. The same should apply to foreign and domestic services, and to foreign and local trademarks, copyrights and patents. This principle of national treatment (giving others the same treatment as one's own nationals) is also found in all the three main WTO agreements, although once again the principle is handled slightly differently in each of these.

National treatment only applies once a product, service or item of intellectual property has entered the domestic market. Therefore, charging customs duty on an import is not a violation of national treatment even if locally-produced products are not charged an equivalent tax.

There are some exceptions to the WTO principles discussed here:

- The WTO allows members to establish bilateral or regional customs unions, or free trade areas (FTAs). Members in such areas enjoy more preferential treatment than those outside the group.

- The WTO also allows members to lower tariffs to developing countries without lowering them for the developed ones. The United States, for example, offers such treatment to developing countries through the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). Due to this system, US companies that are more vulnerable to import competition from developing countries, face greater pressure on cost reduction. If a developing country is not a WTO member, it cannot enjoy such preferences.

- The WTO also allows escape clauses, which are special allowances permitted by the WTO to protect infant industries or to safeguard the economic interests of newly admitted developing countries. These countries may modify or withdraw concessions on customs duties if this is required for the establishment of a new industry that will improve standards of living. They may also restrict imports to safeguard their balance of payments equilibrium, or obtain the necessary exchange for the purchase of goods for the implementation of development plans. Their governments are also allowed to provide assistance to these industries if it helps to safeguard their economies.

Functions of WTO

The WTO was set up to achieve the following functions:

- Elimination of discrimination: The WTO follows the MFN and national treatment principles for the elimination of discrimination among its member nations. This is done to ensure the overall economic development of all member nations based on the principles of free trade.

- Combating protection and trade barriers: The WTO is committed to the removal of all types of protection against free trade, whether it is in the form of import duties or quotas, for whatever reasons they are implemented. The WTO's trade-policy review body regularly monitors the trade policies of its members in order to enhance the degree of market access to members’ markets.

- Resolution of disputes: The WTO functions as a forum for the resolution of disputes of its members through the establishment of panels for this specific purpose. The judicial reach of the WTO is, however, restricted to its members, and non-members cannot benefit from this facility.

- Providing a forum for emerging issues: The WTO is a forum for dealing with emerging issues in the world trading system, such as intellectual property, environmental issues, regional agreements, as well as special sectors such as agriculture, telecommunications, financial services and maritime services. The forum serves to develop new rules through these discussions, such as TRIPS for the governance of issues related to patents, copyrights, trade secrets, and related matters.

Significant Areas of WTO Intervention

Member countries of the WTO have a commitment to rationalize tariffs under the Marrakesh Protocol of 1994. According to this Protocol, developed countries had to cut their average tariff levels on industrial products by 40 per cent in five equal instalments from 1 January 1995. A number of developing and transition economies agreed to reduce tariff levels by two thirds of the percentage agreed upon by the developed countries. Under the Information Technology Agreement of 2007, 40 countries which accounted for more than 92 per cent of trade in information technology products, agreed to eliminate import duties.

WTO members also have a commitment not to increase tariffs above the listed rates known as bound rates, leading to a substantial increase in market security for traders and investors.

WTO AGREEMENTS

The WTO agreements cover trade in goods, services and intellectual property and specify the basic principles of liberalization and the exceptions to the rule. This includes individual countries’ commitments to lower customs tariffs and other trade barriers, and to open markets for services. They also specify a dispute settlement procedure between member countries and prescribe special treatment for developing countries. They require governments to make their trade policies transparent by notifying the WTO about laws in force and measures adopted, through the submission of regular reports to the secretariat on countries’ trade policies.

The WTO agreements fall into a simple structure with six main parts: (1) an umbrella agreement (the Agreement establishing the WTO); (2) GATT for goods; (3) GATS for services; (4) TRIPS for intellectual property; (5) dispute settlement; and (6) reviews of governments’ trade policies.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

The agreement for goods under GATT deals with sector-specific issues such as agriculture, health regulations for farm products, textiles and clothing, product standards, and issues such as import licensing, rules of origin, subsidies, counter measures and safeguards.

Agriculture

The first multilateral agreement on agriculture was introduced in the Uruguay Round, with the basic objective of introducing reform in agriculture to make it more market-oriented. Under the terms of this agreement, developed countries agreed to cut tariffs by an average of 36 per cent in equal steps over the period 1995–2000, while developing countries agreed to make tariff cuts of 24 per cent over a 10 year period. However, the least developed countries were exempted from making these tariff cuts.

Tariffs on all agricultural products are now bound and have been substantially reduced. Almost all import restrictions, which were in the form of quotas, have been converted into tariffs. Market access commitments on agriculture have also eliminated previous import bans on certain products.

The agreement also contains provisions for cutting down domestic support in the form of subsidies or price support. The quantified measure of this is known as aggregate measurement of support (AMS). Developed countries agreed to reduce the total AMS by 20 per cent over a period of six years starting in 1995, while developed countries agreed to make a 30 per cent cut over 10 years. The AMS is calculated on a product-by-product basis by using the difference between the average external reference price for a product and its applied administered price multiplied by the quantity of production. To arrive at the AMS, non-product-specific domestic subsidies are added to total subsidies, calculated on a product-by-product basis. Domestic support in the agricultural sector is categorized as green-, amber-, and blue-box subsidies.5

Amber-box subsidies All domestic support measures considered to distort production and trade fall into the amber box. These include measures to support prices, or subsidies directly related to production quantities. These supports are subject to minimal limits of five per cent of agricultural production for developed countries and 10 per cent for developing countries; WTO members that had larger subsidies than these minimum levels at the beginning of the post-Uruguay Round reform period are committed to reducing them. The US marketing loan programme, which provides a floor on crop prices, is an example of an amber subsidy.6

Blue-box subsidies Blue-box subsidies are also known as the “amber box with conditions”—conditions designed to reduce distortion. Any support that would normally be in the amber box is placed in the blue box if the support also requires farmers to limit production. At present, there are no limits on spending on blue box subsidies. In the current negotiations, some countries want to keep the blue box as it is because they see it as a crucial means of moving away from distorting amber-box subsidies without causing too much hardship. Others want to set limits or reduction commitments, some advocating moving these supports into the amber box. Twenty-two per cent of all EU subsidies to its farm sector are classified to fall in this category.

Green-box subsidies Green-box subsidies are classified as those which do not distort trade, or at most cause minimal distortion. They have to be government-funded (not by charging consumers higher prices), and must not involve price support. These include programmes that are not targeted at particular products, and include direct-income supports for farmers that are not related to (are “decoupled” from) current production levels or prices. They also include environmental protection and regional development programmes. Green-box subsidies are, therefore, allowed without limits, provided they comply with the policy-specific criteria set out in Annexure 2 of the WTO agreements. Examples of green-box subsidies are direct payments to producers, including decoupled income support, and government financial support for income insurance and income safety-net programmes

In the current negotiations, some countries have argued that some of the subsidies listed under this category might not meet the criteria of minimal trade distortion either on account of the large amounts paid, or because of the nature of these subsidies. The July 2004 framework provided a mandate for review and clarification of the green-box criteria. The suggestions aimed to make the eligibility criteria for developed countries more restrictive, and clarify/add additional criteria for covering programmes of developing countries that cause no or minimal trade distortions.

Standards and Safety Measures

The Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) lays down basic rules on food, safety, and plant health standards. It allows governments to set their own rules based on science and health, which it deems necessary for the protection of human, animal and plant life or health, as long as they don't discriminate between countries or act as disguised protectionism.

The Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) complements the attempts to make sure that regulations, standards, testing, and certification procedures do not create unnecessary obstacles to trade.

Trade in Textiles

World trade in textiles was governed by the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA)—a framework for bilateral agreements including unilateral actions that established quotas limiting imports into member countries. Since the MFA went against the basic principles of the GATT, it was replaced by WTO's Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) from 1995. The Agreement was supervised by a Textiles Monitoring Body (TMB), which monitors actions under the Agreement to ensure that they are consistent. The ATC came to an end on 1 January 2005 and opened up immense opportunities and challenges for developing countries.

General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

GATS is the first set of rules established governing international trade in services. It owes its existence to the growing importance of the service sector in the world economy and covers all internationally traded services, such as banking, telecommunications, tourism and other professional services. It covers these services in the following modes:

- Mode 1 covers services supplied from one country to another, such as international telephone calls. It is known as cross-border supply.

- Mode 2 covers consumers or firms making use of a service in another country, such as tourism. It is known as consumption abroad.

- Mode 3 refers to services termed commercial presence, such as a foreign company setting up subsidiaries or branches abroad.

- Mode 4 is known as presence of natural persons and includes individuals travelling to foreign countries to supply services, such as fashion models or consultants.

Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)

TRIPS lays down the minimum standards for the protection of intellectual property rights as well as the procedures and remedies for their enforcement in a multilateral trading system. The TRIPS agreement is an attempt to narrow the gap in the way intellectual property is protected in varying degrees across the world and to bring it under common international rules. It also establishes a mechanism for consultation and surveillance at an international level to ensure compliance with these standards by member countries at the national level. Rapid developments in technology have led to increasing trade in films, music, and computer software with increasing invention, innovation research, and design in all of these. The provisions under TRIPS are based on important existing conventions such as the Protection of Industrial Property and the Berne Convention. Its provisions are applicable to intellectual property rights related to patents, copyrights, trademarks, industrial designs, and layout designs of integrated circuits. According to this agreement, developed countries were given one year to ensure that their law and practices were in conformity with TRIPS regulations, whereas developing and transition economies were given five years. The least developed countries were given 11 years to make the grade, but this was subsequently extended to 2016 for pharmaceutical patents.

Agreement on Trade-related Investment Measures (TRIMS)

TRIMS recognizes that governments often impose conditions on foreign investors to encourage investment according to national priorities. The provisions of TRIMS, therefore, stipulate that no member shall apply any measures in violation of the national treatment principles of the GATT and discriminate against foreigners or foreign products. It also prohibits investment measures that place a restriction on quantities and measures requiring a certain percentage of local procurement (local content requirement), and discourages measures which limit imports or set targets for exports (trade balancing requirements).

WTO: AN EVALUATION

The WTO served as an effective enforcement agency in the first decade of its life, settling more than 325 disputes between 1995 and 2005.7 The WTO's efforts to promote free trade in the global economy have been encouraging although it has met with quite a few setbacks and there still remains a large unfinished agenda.

Developing-country Issues

Developing countries allege that they fail to benefit from the trade liberalization and protection of intellectual property under the WTO framework, since they have neither a good supply base necessary for trade expansion nor strong intellectual property rights (IPRs) for financial gains.

Developed countries often take advantage of escape routes and loopholes in the WTO agreements. For instance, the ATC left the choice of products to importing countries. Developed countries chose only those products for liberalization which were not under import restraints without actually liberalizing their textile imports.

Dispute-resolution Mechanism

It has been alleged that the WTO's dispute-settlement mechanism suffers from complete lack of transparency and it is infamously opaque in revealing how settlements were reached. Whether settling disputes or negotiating new trade relations, it is rarely clear which nations are in on the decision-making processes.

In this context, the WTO is seen as a clique of the developed nations forcing agreements that allow them to exploit less developed nations. This clique uses the WTO to open up developing nations as markets to sell, while protecting their own markets against weaker nations’ products. This view has its valid points, as the most economically powerful nations seem to set the WTO agenda, and were the first to pass anti-dumping acts to protect favoured domestic industries, while also opposing similar actions by less powerful nations.

A substantial amount of negotiations take place in small groups where developing nations are not present, but they are expected to ratify these when they are discussed in large groups.

Subsidies in Agriculture

Agricultural subsidies have been a major obstacle in WTO negotiations. The collapse of the Doha Round talks at Cancun in September 2003 have been blamed on the refusal of developed countries to dramatically reform their agricultural domestic-support policies.8 For the first time, developing countries organized themselves to form a powerful coalition that was able to resist mediocre reform proposals put forth by the United States and the EU. Cotton subsidies, in particular, became a focal point of talks as the Communaute Financiere Africaine (CFA) countries, who together are the third largest cotton exporters, claimed that US agricultural support causes an oversupply of US cotton, which severely depresses cotton prices and consequently their export earnings. It was estimated that CFA countries lose more than USD 130 million each year due to US cotton support. Estimates suggest that between 1995 and 2009, the United States doled out farm-aid payments to the tune of a quarter of a trillion. The three most heavily subsidized crops in the United States were corn, wheat, and cotton.9

The EU's common agricultural policy (CAP), which provides EUR 55 billion as farm subsidies each year, accounts for roughly 40 per cent of the total EU budget and supports farmers across the 27-nation bloc. In 2009, farmers in France received the most farm-aid payments, while sugar-processing companies topped the list of beneficiaries. The sugar-processing firms in Europe were the recipient of large sums of aid payment, as part of EU reforms to help farmers move out of unproductive sectors. The largest single payment under CAP in 2009 went to a French sugar company that collected EUR 178 million in support.

The other sector which receives the highest EU farm subsidies is the dairy sector. Following a steep tumble in the price of milk, tens of thousands of farmers went on strike to demand stronger EU intervention, pouring millions of litres of milk onto their fields in protest. To quell the outcries, European officials used CAP funds to purchase surplus stocks, help pay for private storage, and provide dairy farmers with export subsidies. At the WTO, developing-country exporters expressed their disappointment at the reintroduction of export subsidies for EU dairy products in January 2009. The EU, under the Doha negotiations, had earlier committed to eliminate export subsidies by 2013.

Agriculture continues to be an important source of livelihood for large parts of the developing and the less developed world. Its members have, therefore, been insisting on special and differential treatment in several aspects of WTO dealings, including agriculture, in the Doha Round. It is in this context that countries like India have been insisting that the Doha agricultural outcome must include the removal of distorting subsidies and protection to ensure a level playing field. It also wants appropriate provisions to safeguard food and livelihood security to meet rural-development needs.

Trade in Services

The Uruguay Round brought in the issue of trade in services for the first time, which was further taken up by the WTO, as were issues on foreign direct investment (FDI). The global telecommunications industry and financial services were the first to come within this ambit. As a result, in February 1997, 68 countries accounting for more than 90 per cent of world telecommunications revenue opened up their markets to foreign competition and agreed to abide by a set of common rules. By 1 January 1998, the largest markets, including the United States, Japan, and the EU, were fully liberalized. The pact covered all forms of basic telecommunication services, including voice telephony, data and fax transmissions, and satellite and radio communications.

In December 1997, there was an agreement to liberalize cross-border trade in financial services.10 The deal, signed by 102 countries, covered more than 95 per cent of the world financial services market, including banking, securities and insurance. It also covered trade and FDI. This led to the opening up of the US and EU financial services markets almost completely, and important concessions by many Asian countries allowing foreign participation in the financial services sector.

Future Challenges for WTO

Some challenges that are continuously being faced by the WTO and will continue in the future are discussed here.

Farm Subsidies

The WTO meeting at Seattle in November 1999 for the reduction of barriers to cross-border trade in agricultural products and trade and investment was an inconclusive, acrimonious session. The deadlock on the agenda arose out of the clash of interests of the United States and the EU over farm subsidies. While the United States advocated the elimination of subsidies on a priority basis, the EU with its politically powerful farm lobby and long history of farm subsidies was unwilling to take this step.

Labour Practices

The United States wanted the WTO to allow governments to impose tariffs on goods imported from countries which did not abide by what the United States considered fair labour practices. This led to violent protests from the developing world, which considered this a legal route to restrict imports from poor, low-cost developing countries.

Anti-Dumping Actions