The nexus of feedback and improvement

Abstract:

Student feedback on their experience is ubiquitous but is only useful if valued and acted upon. Generic student surveys are often used but more fine-grained surveys are more effective in informing improvement initiatives. To make an effective contribution to internal improvement processes, students’ views need to be integrated into a regular and continuous cycle of analysis, action and report back to students on action taken. Student feedback often assumes a consumerist view rather than a transformative view of learning and hence a focus on facilities and teaching rather than learning. As well as feedback from students on their learning environment, feedback to students on their work and progress is vital for transformative learning. Feedback to students is often poor and there are various ways to improve such feedback and hence empower students as effective autonomous learners.

Introduction

Student feedback on aspects of their experience is ubiquitous. Indeed, it is now expected. The recent Parliamentary Select Committee report in the UK (House of Commons, 2009) concluded, inter alia, with the following student comment: ‘What contributes to a successful university experience is an institution which actively seeks, values and acts on student feedback’ (p. 131).

Carr et al. (2005) commented:

Student surveys are perhaps one of the most widely used methods of evaluating learning outcomes (Leckey and Neill, 2001: 24) and teaching quality. Students may have a certain bias which influences their responses, however, the student perspective is advantageous for being much more immediate than analyses of, for example, completion and retention rates. Further, the view presented in the survey is that of the learner, ‘the person participating in the learning process’ (Harvey, 2001). Harvey also identified the value in the richness of information that can be obtained through the use of student surveys (Harvey, 2001).

Much earlier, Astin (1982), for example, had argued that students are in a particularly good position to comment upon programmes of study and thus to assist institutions to improve their contribution to student development. Hill (1995) later argued, from a student perspective, that students are ‘often more acutely aware of problems, and aware more quickly’ than staff or visiting teams of peers; which is, ‘perhaps, the primary reason for student feedback on their higher education to be gathered and used regularly’ (p. 73).

However, this has not always been the case. Twenty years ago, systematic feedback from students about their experience in higher education was a rarity. With the expansion of the university sector, the concerns with quality and the growing ‘consumerism’ of higher education, there has been a significant growth of, and sophistication in, processes designed to collect views from students.

Most higher education institutions, around the world, collect some type of feedback from students about their experience of higher education. ‘Feedback’ in this sense refers to the expressed opinions of students about the service they receive as students. This may include: perceptions about the learning and teaching; the learning support facilities, such as libraries and computing facilities; the learning environment, such as lecture rooms, laboratories, social space and university buildings; support facilities including refectories, student accommodation, sport and health facilities and student services; and external aspects of being a student, such as finance, car parking and the transport infrastructure.

Student views are usually collected in the form of ‘satisfaction’ feedback in one way or another; albeit some surveys pretend that by asking ‘agree-disagree’ questions they are not actually asking about satisfaction with provision. Sometimes, but all too rarely, there are specific attempts to

obtain student views on how to improve specific aspects of provision or on their views about potential or intended future developments.

The reaction to student views also seems to have shifted. Baxter (1991) found that over half the respondents in a project he reported experienced improved job satisfaction and morale and almost all were influenced by student evaluation to change their teaching practice. Massy and French (2001) also stated, in their review of the teaching quality in Hong Kong, that ‘staff value and act upon student feedback’ and are ‘proactive in efforts to consult with students’ (p. 38). However, more recently, Douglas and Douglas (2006) suggested that staff have very little faith in student feedback questionnaires, whether module or institutional. This is not so surprising when student feedback processes tend to be bureaucratised and disconnected from the everyday practice of students and teaching staff; a problem that is further compounded by a lack of real credit and reward for good teaching.

Ironically, although feedback from students is assiduously collected in many institutions, it is less clear that it is used to its full potential. Indeed, a question mark hangs over the value and usefulness of feedback from students as collected in most institutions. The more data institutions seek to collect, the more cynical students seem to become and the less valid the information generated and the less the student view is taken seriously. Church (2008) remarked that ‘students can often feel ambivalent about completing yet another course or module questionnaire. This issue becomes particularly acute when students are not convinced of the value of such activity –- particularly if they don’t know what resulted from it.’

In principle, feedback from students has two main functions: internal information to guide improvement; and external information for potential students and other stakeholders. In addition, student feedback data can be used for control and accountability purposes when it is part of external quality assurance processes. This is not discussed here as it is in fact a trivial use of important data, which has as its first priority improvement of the learning experience.

Improvement

It is not always clear how views collected from students fit into institutional quality improvement policies and processes. To be effective in quality improvement, data collected from surveys and peer reviews must be transformed into information that can be used within an institution to effect change.

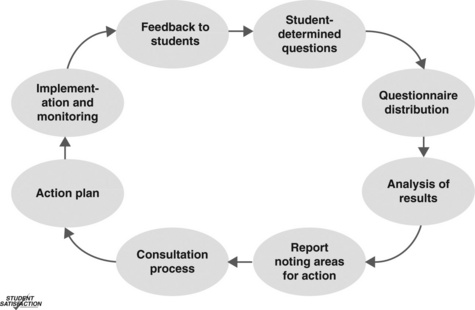

To make an effective contribution to internal improvement processes, views of students need to be integrated into a regular and continuous cycle of analysis, reporting, action and feedback, be it at the level of an individual taught unit or at the institutional level (Figure 1.1). In many cases it is not always clear that there is a means to close the loop between data collection and effective action, let alone feedback to students on action taken, even within the context of module feedback questionnaires. Closing the loop is, as various commentators have suggested, an important, albeit neglected, element in the student feedback process (Ballantyne, 1997; Powney and Hall, 1998; Watson, 2003; Palermo, 2004; Walker-Garvin, undated). Watson (2003) argued that closing the loop and providing information on action taken encourages participation in further research and increases confidence in results, as well as it being ethical to debrief respondents. It also encourages the university management to explain how they will deal with the highlighted issues.

Making effective use of feedback requires that the institution has in place an appropriate system at each level that:

![]() identifies and delegates responsibility for action;

identifies and delegates responsibility for action;

![]() encourages ownership of plans of action;

encourages ownership of plans of action;

![]() requires accountability for action taken or not taken;

requires accountability for action taken or not taken;

![]() communicates back to students on what has happened as a result of their feedback (closes the loop);

communicates back to students on what has happened as a result of their feedback (closes the loop);

As Yorke (1995) noted, ‘The University of Central England has for some years been to the fore in systematising the collection and analysis of data in such a way as to suggest where action might be most profitably directed (Mazelan et al., 1992)’ (p. 20). However, establishing an effective system is not an easy task, which is why so much data on student views is not used to effect change, irrespective of the good intentions of those who initiate the enquiries. There is much latent inertia in seeing through the implications of collecting student feedback, which is reflected in student indifference to many feedback processes. It is more important to ensure an appropriate action cycle than it is to have in place mechanisms for collecting data. Williams (2002) extends this and maintains that it is more important to focus attention on the use of results and sustaining change rather than on the results themselves.

External information

In an era when there is an enormous choice available to potential students, the views of current students offer a useful information resource. Yet very few institutions make the outcomes of student feedback available externally. The University of Central England in Birmingham (UCE) (now Birmingham City University), which, as Rowley (1996: 246) said, ‘pioneered’ student feedback, was also exceptional in publishing, from its inception in 1988, the results of its institution-wide student feedback survey, which reported to the level of faculty and major programmes.1 Institutions abroad that have implemented the UCE Student Satisfaction approach, including Auckland University of Technology (Horsburgh, 1998) and Lund University (Torper, 1997) have published the results. However, the norm in Britain is to consider that student views are confidential to the university.

Preoccupation with surveys

There is a debilitating assumption that feedback from students should be sought via a survey, usually a questionnaire. More than a decade ago, Rowley (1996) noted that: ‘Commitment to the continuing improvement of quality within institutions has led to the collection of feedback from students. Questionnaires are the prime tool used in the process’ (p. 224).

The following sections explore typical questionnaire approaches but prior to that, an important note on alternative approaches. Questionnaires, indeed surveys of any sort, are very poor ways of collecting student feedback. First, they are indirect and often there is no clear indication to students of the value or use of the data provided. Secondly, and more importantly, surveys rarely, if ever, provide a nuanced understanding of student concerns, issues and acknowledgements. Thirdly, because of this lack of nuanced understanding, surveys usually end up with open comments that seem to be in direct opposition to the generally satisfactory ratings from closed questions. This is because the structure is such that students tend, in the main, to use the open comments to raise complaints or concerns that the closed questions do not adequately address. Fourthly, most surveys do not explore how improvements could be made as the student view on appropriate improvements is rarely directly asked and, usually, the students have not been involved in the design of the survey in the first place. Hence, there is a significant degree of student indifference as the surveys seem to be simply providing a legitimation for inaction.

A much more useful means of exploring the student perspective is through direct dialogue. This can occur in many ways, for example, though face-to-face discussion groups within the classroom, ‘chaired’ by the lecturer, a student or an external facilitator (with or without the lecturer present). These may be ad hoc discussions, formally-minuted scheduled events, or based on focus group sessions. Discussions may be conducted virtually, through blogs, online discussion groups or webinars, for example.

The representative system in which students are members of committees at all levels also provides a means for obtaining feedback, as also does the formal complaints system. Rowley (1996) noted that:

In addition to the formal questionnaire-based survey many institutions make use of complaints systems and suggestion boxes, which provide useful feedback, but it is difficult for managers to gauge the extent to which these are indicative of user opinion, or are representative of only the vociferous minority. However, these can be used alongside annual satisfaction surveys, not least because they provide a quicker means of communication than a survey on an annual cycle. (p. 248)

However, most valuable, at least for the teaching team, is the informal feedback provided impromptu in classes, during tutorials, via corridor or coffee-break chats or through e-mails. This informal feedback is ‘student-centred’, to the point, and timely. It may be from Rowley’s ‘vociferous minority’, but a reflective lecturer can discern when there is a genuine issue for consideration and when someone is, for example, venting frustration.

However, this requires that staff (academics, administrators and managers) listen to what they are being told rather than ignoring it; reconstituting it as unrealistic, rebutting criticisms, or assuming students do not know what is best for them, or any of the other numerous techniques adopted to ensure that they do not hear the unwelcome messages.

Types of surveys

The predominant ‘satisfaction’ survey takes five forms:

![]() institution-level satisfaction with the total student experience or a specified sub-set;

institution-level satisfaction with the total student experience or a specified sub-set;

![]() faculty-level satisfaction with provision;

faculty-level satisfaction with provision;

![]() programme-level satisfaction with the learning and teaching and related aspects of a particular programme of study (for example, BA Business Studies);2

programme-level satisfaction with the learning and teaching and related aspects of a particular programme of study (for example, BA Business Studies);2

![]() module-level feedback on the operation of a specific module or unit of study (for example, Introduction to Statistics);

module-level feedback on the operation of a specific module or unit of study (for example, Introduction to Statistics);

Institution-level satisfaction

Systematic, institution-wide student feedback about the quality of the total educational experience was an area of growing activity in many countries. However, innovations in this area have been thwarted by the introduction of banal national surveys designed to provide simplistic comparative data by which institutions can be compared. The upshot is more concern with ranking tables than with addressing underlying issues (Williams and Cappuccini-Ansfield, 2007). The mock accountability and misleading public information of such national surveys constitutes a fatuous waste of money and effort.

Institution-level satisfaction surveys are almost always based on questionnaires, which mainly consist of questions with pre-coded answers augmented by one or two open questions. In the main, these institution-wide surveys are (or should be) undertaken by a dedicated unit with expertise in undertaking surveys, producing easily interpretable results to schedule.

Institution-wide surveys tend to encompass most of the services provided by the university and are not to be confused with standardised institutional forms seeking feedback at the programme or module level (discussed below). In the main, institution-wide surveys seek to collect data that provides information for management designed to encourage action for improvement and, at their best, the surveys are based on the student perspective rather than on the preconceived notions of managers. Such surveys can also provide an overview of student opinion for internal and external accountability purposes, such as reporting to boards of governors or as evidence to quality auditors.

The way the results are used varies. In some cases there is a clear reporting and action mechanism. In others, it is unclear how the data helps inform decisions. In some cases the process has the direct involvement of the senior management, while in other universities’ action is realised through the committee structure. In some cases, where student unions are a major factor in decision-making, such as at Lund University, they play a significant role in the utilisation of the student feedback for improvement (Torper, 1997).

Feedback to students about outcomes of surveys is recognised as an important element (Williams and Cappuccini-Ansfield, 2007) but is not always carried out effectively, nor does it always produce the awareness intended. Some institutions utilise current lines of communication between tutors and students or feed back through the student unions and student representatives. All of these forms depend upon the effectiveness of these lines of communication. Other forms of feedback used include articles in university magazines, posters and summaries aimed at students. The satisfaction approach developed at UCE, and adopted widely, provided a basis for internal improvement in a top-down/bottom-up process. At UCE, it involved the vice-chancellor, deans and directors of services. There was a well-developed analysis, reporting, action and feedback cycle. The results of the student feedback questionnaire were reported to the level of faculty and programme. The report was written in an easily accessible style, combining satisfaction and importance ratings that clearly showed areas of excellence and areas for improvement. The report was published (with an ISBN number) and was available in hard copy and on a public website. The action that followed the survey was reported back to the students through an annual publication. The approach worked, as the level of student satisfaction improved over a period stretching back nearly two decades (Kane et al., 2008).

Institutions that have used and adapted the UCE model include Sheffield Hallam University, Glamorgan University, Cardiff Institute of Higher Education (now University of Wales Institute, Cardiff), Buckingham College of Higher Education (now Buckinghamshire New University), University of Greenwich and University of Central Lancashire as well as overseas institutions such as Auckland University of Technology (New Zealand), Lund University (Sweden), City University (Hong Kong) and Jagiellonian University (Poland). All of these institutions have a similar approach, collecting student views to input into management decision-making. Where they varied is in the degree to which they made the findings public and produced reports for students outlining actions that have resulted from the survey.

When developing an institution-wide survey it is recommended that:

![]() They should provide both data for internal improvement and information for external stakeholders, therefore the results and subsequent action should be published.

They should provide both data for internal improvement and information for external stakeholders, therefore the results and subsequent action should be published.

![]() If the improvement function is to be effective, it is first necessary to establish an action cycle that clearly identifies lines of responsibility and feedback.

If the improvement function is to be effective, it is first necessary to establish an action cycle that clearly identifies lines of responsibility and feedback.

![]() Surveys need to be tailored to fit the improvement needs of the institution. Making use of stakeholder inputs (especially those of students) in the design of questionnaires is a useful process in making the survey relevant. System-wide generic questions are of little value.

Surveys need to be tailored to fit the improvement needs of the institution. Making use of stakeholder inputs (especially those of students) in the design of questionnaires is a useful process in making the survey relevant. System-wide generic questions are of little value.

![]() Only information that will be acted upon is collected.

Only information that will be acted upon is collected.

![]() Importance as well as satisfaction ratings are recommended as this provides key indicators of what students regard as crucial in their experience and thus enables a clear action focus.

Importance as well as satisfaction ratings are recommended as this provides key indicators of what students regard as crucial in their experience and thus enables a clear action focus.

![]() For improvement purposes, reporting needs to be to the level at which effective action can be implemented; for example, programme organisation needs to be reported to the level of programmes, computing facilities to the level of faculties, learning resources to the level of libraries.

For improvement purposes, reporting needs to be to the level at which effective action can be implemented; for example, programme organisation needs to be reported to the level of programmes, computing facilities to the level of faculties, learning resources to the level of libraries.

![]() Reports need to be written in an accessible style: rather than tables densely packed with statistics, data should be converted to a simple grading that incorporates satisfaction and importance scores, where the latter are used, thus making it easy for readers to identify areas of excellence and areas for improvement.

Reports need to be written in an accessible style: rather than tables densely packed with statistics, data should be converted to a simple grading that incorporates satisfaction and importance scores, where the latter are used, thus making it easy for readers to identify areas of excellence and areas for improvement.

Faculty-level satisfaction with provision

Faculty-level surveys (based on pre-coded questionnaires) are similar to those undertaken at institution level. They tend to focus only on those aspects of the experience that the faculty controls or can directly influence. They often tend to be an unsatisfactory combination of general satisfaction with facilities and an attempt to gather information on satisfaction with specific learning situations. In most cases, these surveys are an additional task for faculty administrators; they are often based on an idiosyncratic set of questions and tend not to be well analysed, if at all. They are rarely linked into a meaningful improvement action cycle.

Where there is an institution-wide survey, disaggregated and reported to faculty level, faculty-based surveys tend to be redundant. Where faculty surveys overlap with institutional ones, there is often dissonance that affects response rates.

Faculty-level surveys are not really necessary, if well-structured institution-wide surveys are in place. If faculty-level surveys are undertaken it is recommended that:

![]() they do not clash with or repeat elements of existing institution-wide surveys;

they do not clash with or repeat elements of existing institution-wide surveys;

![]() where both coexist, it is probably better to attempt to collect faculty data through qualitative means, focusing on faculty-specific issues untouched by institution-wide surveys;

where both coexist, it is probably better to attempt to collect faculty data through qualitative means, focusing on faculty-specific issues untouched by institution-wide surveys;

![]() they are properly analysed and linked into a faculty-level action and feedback cycle, otherwise cynicism will rapidly manifest itself and undermine the credibility of the whole process.

they are properly analysed and linked into a faculty-level action and feedback cycle, otherwise cynicism will rapidly manifest itself and undermine the credibility of the whole process.

Programme-level satisfaction with the learning and teaching

Programme-level surveys are not always based on questionnaires, although most tend to be. In some cases, feedback on programmes is solicited through qualitative discussion sessions, which are minuted. These may make use of focus groups. Informal feedback on programmes is a continuous part of the dialogue between students and lecturers. As identified above, informal feedback is an important source of information for improvement at this level. However, as Jones (2003) noted:

What is receiving less attention, and stands to be eclipsed as a means of measuring quality, are traditional quality assurance measures, administered by academics at the micro (delivery) level both as ongoing continuous improvement in response to verbal feedback from students, and in response to periodic, often richly qualitative, feedback from students on completion of a particular course of study. (p. 24)

James and McInnis (1997) had also shown that ‘Less structured evaluation through informal discussion between staff and students was also considered an important means of receiving feedback on student satisfaction in most programmes’ (p. 107).

Programme-level surveys tend to focus on the teaching and learning, course organisation and programme-specific learning resources. However, in a modularised environment, programme-level analysis of the learning situation tends to be ‘averaged’ and does not necessarily provide clear indicators of potential improvement of the programme without further enquiry at the module level. The link into any action is far from apparent in many cases. Where a faculty undertakes a survey of all its programmes of this type, there may be mechanisms, in theory, to encourage action but, in practice, the time lag involved in processing the questionnaires by hard-pressed faculty administrators tends to result in little timely improvement following the feedback.

In a modularised environment, where modular-level feedback is encouraged (see below), there is less need for programme-level questionnaire surveys. Where the institution-wide survey is comprehensive and disaggregates to the level of programmes, there is also a degree of redundancy in programme-level surveys. Again, if programme-level and institutional-level run in parallel there is a danger of dissonance.

Programme questionnaires are particularly common for final-year students coming to the end of their studies, who are asked to reflect back on the whole degree. The standardised programme evaluation approach reached its nadir in Australia with the development of the Course Evaluation Questionnaire (CEQ). This was a national minimalist survey aimed at graduates of Australian higher education institutions. The cost benefit of the CEQ has been a continuing area of debate in Australia.

Programme-level questionnaire surveys are probably not necessary if the institution has both a well-structured institution-wide survey, reporting to programme level, and structured module-level feedback. If programme-level surveys are undertaken it is recommended that:

![]() they do not clash with institution-wide surveys or module-level feedback if they exist;

they do not clash with institution-wide surveys or module-level feedback if they exist;

![]() where programme-level information is needed for improvement purposes, it is probably better to obtain qualitative feedback on particular issues through discussion sessions or focus groups;

where programme-level information is needed for improvement purposes, it is probably better to obtain qualitative feedback on particular issues through discussion sessions or focus groups;

![]() they must be properly analysed and linked into a programme-level action and feedback cycle.

they must be properly analysed and linked into a programme-level action and feedback cycle.

Module-level feedback

Feedback on specific modules or units of study provides an important element of continuous improvement. The feedback tends to focus on the specific learning and teaching associated with the module, along with some indication of the problems of accessing module-specific learning resources. Module-level feedback, both formal and informal, involves direct or mediated feedback from students to teachers about the learning situation within the module or unit of study.

The primary form of feedback at this level is direct informal feedback via dialogue. However, although this feedback may often be acted upon, it is rarely evident in any accounts of improvements based on student feedback. It constitutes the most important form of feedback in that it is probably the most effective spur to action on the part of receptive and conscientious academics in the development of the teaching and learning situation. Not all teachers are receptive to informal feedback and arrogant or indifferent lecturers can be found, in all institutions, who only hear what they want to hear and treat student views with indifference.

In most institutions, there is a requirement for some type of formal collection and reporting of module-level feedback, usually to be included in programme annual reports. Some institutions do not specify a particular data collection process and the lecturers decide on the appropriate method for the formal collection of feedback. Increasingly, though, institutions are imposing formal questionnaire templates, using online data collection methods; often with very low response rates, which provides another excuse for lecturers and managers to ignore the results (Douglas and Douglas, 2006).

Module-level questionnaire feedback is often superficial, generating satisfactory answers to teacher performance questions in the main. This results in little information on what would improve the learning situation and, because of questionnaire-processing delays, rarely benefits the students who provide the feedback. The use of questionnaires tends to inhibit qualitative discussion at the unit level. As Lomas and Nicholls (2005) pointed out, much of the evaluation of teaching rests largely on student feedback and often individuals within departments ‘become objects of that evaluation, rather than participants within the process’ (p. 139).

Direct, qualitative feedback is far more useful in improving the learning situation within a module of study. Qualitative discussion between staff (or facilitators) and students about the content and approach in particular course units or modules provides a rapid and in-depth appreciation of positive and negative aspects of taught modules. If written feedback is required, open questions on questionnaires are used that encourage students to say what would constitute an improvement for them, rather than rating items on a schedule drawn up by a teacher or, worse, an administrator.

However, qualitative feedback is sometimes seen as more time-consuming to arrange and analyse and, therefore, as constituting a less popular choice than handing out questionnaires or asking students to complete an online survey. Where compliance overshadows motivated improvement, recourse to questionnaires is likely.

In many instances, questionnaires used for module-level feedback are not analysed properly or in a timely fashion unless controlled by a central bureaucratic unit. Although most institutions insist on the collection of module-level data, the full cycle of analysis, reporting, action and feedback to originators of the data rarely occurs.

Module-level feedback is vital for the ongoing evolution of modules and the teaching team need to be responsive to both formal and informal feedback. It is, therefore, recommended that feedback systems at the module level:

![]() should include both formal and informal feedback;

should include both formal and informal feedback;

![]() should complement institution-wide surveys, which cannot realistically report to module level;

should complement institution-wide surveys, which cannot realistically report to module level;

![]() should be tailored to the improvement and development needs of the module (and therefore ‘owned’ by the module team), which obviates the need for standardised, institution-wide, module-level questionnaires that intimate compliance and accountability rather than improvement;

should be tailored to the improvement and development needs of the module (and therefore ‘owned’ by the module team), which obviates the need for standardised, institution-wide, module-level questionnaires that intimate compliance and accountability rather than improvement;

![]() must ensure appropriate analysis of the data and link into a modulelevel action and feedback cycle;

must ensure appropriate analysis of the data and link into a modulelevel action and feedback cycle;

![]() do not need to be reported externally but should form part of internal programme reviews.

do not need to be reported externally but should form part of internal programme reviews.

Appraisal of teacher performance by students

Some institutions focus on the performance of teaching staff rather than wider aspects of student satisfaction. Ewell (1993) noted projects being conducted by, inter alia, Astin and Pace in the USA, where feedback questionnaires played a considerable part in the appraisal of academics’ performance. As a result of government pressure in the 1990s, institutions in the UK went through a period of collecting student views on the performance of particular teachers, known as ‘teacher assessment’. Marsh and Roche (1993) developed the Students Evaluations of Educational Quality (SEEQ) instrument, designed to provide both diagnostic feedback to faculty that will be useful for the improvement of teaching and to provide a measure of teaching effectiveness to be used in personnel and administrative decision-making. Many institutions around the world use, or have used, standardised surveys of student appraisal of teaching, especially where there are a lot of part-time teachers (for example, at the London School of Economics, UK and Tuiuti University, Parana, Brazil).

The use of student evaluations of teacher performance is sometimes part of a broader peer and self-assessment approach to teaching quality. In some cases, they are used as part of the individual review of staff and can be taken into account in promotion and tenure situations, which was the case at Wellington and Otago Universities in New Zealand and in many institutions in the United States.

Teacher-appraisal surveys may provide some inter-programme comparison of teacher performance. However, standardised teacher-appraisal questionnaires tend, in practice, to focus on a limited range of areas and rarely address the development of student learning. Often, the standardised form is a bland compromise designed by managers or a committee that serves nobody’s purposes. They are often referred to by the derogatory label of ‘happy forms’, as they are usually a set of questions about the reliability, enthusiasm, knowledge, encouragement and communication skills of named lecturers. Student appraisal of teachers tends to be a blunt instrument. Depending on the questions and the analysis, it has the potential to identify very poor teaching but, in the main, the results give little indication of how things can be improved. Appraisal forms are rarely of much use for incremental and continuous improvement.

In the vast majority of cases, there is no feedback at all to students about outcomes. Views on individual teacher performance are usually deemed confidential and subject to closed performance-review or development interviews with a senior manager. Hence, there is no opportunity to close the loop. At Auckland University, for example, the Student Evaluation of Courses and Teaching (SECAT) process was managed by the lecturers themselves and the results only passed on to managers in staff development interviews if the lecturer wanted to. Copenhagen Business School is a rare example of an institution that, in the 1990s, published the results within the institution.

Students’ appraisal of teacher performance has a limited function, which, in practice, is ritualistic rather than improvement-oriented. Any severe problems are usually identified quickly via this mechanism. Repeated use leads to annoyance and cynicism on the part of students and teachers. Students become disenchanted because they rarely receive any feedback on the views they have offered. Lecturers become cynical and annoyed because they see student appraisal of teaching as a controlling rather than improvement-oriented tool. Thus, it is recommended that:

![]() use of student appraisal of teaching should be sparing;

use of student appraisal of teaching should be sparing;

![]() if used, avoid endlessly repeating the process;

if used, avoid endlessly repeating the process;

![]() if used, ask questions about the student learning as well as the teacher performance;

if used, ask questions about the student learning as well as the teacher performance;

![]() ensure that action is taken, and seen to be taken, to resolve and monitor the problems that such appraisals identify;

ensure that action is taken, and seen to be taken, to resolve and monitor the problems that such appraisals identify;

Multiple surveys: cosmetic or inclusive?

Institutions often have a mixture of the different types of student feedback, to which might be added graduate and employer surveys. The information gathered is, far too often, simply that – information. There are many circumstances when nothing is done with the information. It is not used to effect changes. Often it is not even collected with a use in mind. Perhaps, far too often, it is a cosmetic exercise.

There is more to student feedback than collecting data and the following are important issues. If collecting student views, only collect what can be made use of. It is counterproductive to ask students for information and then not use it. Students become cynical and uncooperative if they think no one really cares about what they think. It is important to heed, examine and make use of student views, whether provided formally or informally. However, if data from surveys of students is going to be useful, then it needs to be transformed into meaningful, clearly reported, information that can be used at the appropriate level to guide improvement. It is important to ensure that action takes place on the basis of student views and that action is seen to take place. This requires clear lines of communication, so that the impact of student views is fed back to students. In short, there needs to be a line of accountability back to the students to close the circle, whether that be at the institution or module level. It is not sufficient that students find out indirectly, if at all, that they have had a role in institutional policy.

Qualitative feedback is far more valuable and nuanced for improvement purposes than responses from standardised quantitative questionnaires. Jones (2003) argued that it is a mistake for institutional managers and central administrators to rely on formal survey data.

Furthermore, there is often rich qualitative feedback (both formal and informal) collected at the decentralised educational delivery point that it is not easy to summarise for use at a central level … Without this rich depth of feedback, centrally administered quantitative surveys often distort student feedback. What is then required is a means to link the two levels and forms of student feedback as part of a holistic quality assessment. (p. 225)

Williams and Cappuccini-Ansfield (2007) also made it clear, in their seminal paper, that relying on national surveys is inadequate for improvement purposes. Comparing the UK generic national student survey (NSS) and, for example, the tailored approach embodied in the Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS) approach (Harvey et al., 1997) that reflects the specific circumstances and issues in an institution, they noted that:

the two are very different survey instruments, created for different purposes and should be used accordingly. The NSS is designed as a broad brush instrument, short and simple, which aims to measure the concept of quality, using a single format that can be used at all higher education institutions. The SSS, in contrast, is a detailed instrument, which aims to measure satisfaction with all aspects of the student experience and is tailored specifically to the needs of students at a particular institution. The SSS is specifically designed to be central to internal continuous quality improvement processes, whereas the NSS cannot be effectively used for this purpose … There are dangers with the nation-wide league table approach enabled by the NSS that only the minimum information, in this case, mean scores, is used to make crude comparisons between the value for money of very different institutions. The SSS helps to address an individual institution’s accountability by involving students in the quality process, both by giving feedback to them and responding to feedback from them. There is value in using surveys to provide information about institutions for prospective students, but there are potential problems with making fair comparisons between institutions. (p. 170)

They also pointed out that ‘final-year students filling in the national survey may give favourable scores if they want their degree from that institution to be valued’ (Williams and Cappuccini-Ansfield, 2007: 171). Indeed, there were cases in the UK of staff attempting to manipulate students to give high ratings so that the institution would appear higher on the league tables (Attwood, 2008; Mostrous, 2008; Furedi, 2008; Swain, 2009).

Williams and Cappuccini-Ansfield also highlighted the danger that NSS data ‘will be used simplistically, without a great deal of thought to how well it represents the quality of education offered by the institution’. Further, ‘Its administration can interfere with each institution’s important internal quality processes and most certainly can never replace them’ (Williams and Cappuccini-Ansfield, 2007: 171).

The recent British Parliamentary Select Committee reviewing higher education also remarked on the limitations of the NSS.

101. We accept that the National Student Survey is a good starting point but caution against an over-reliance on it. The University of Hertfordshire said that there was ‘a significant tension’ with the National Student Survey being a tool for improvement and also used in league tables. It noted that there were ‘documented instances of abuse (and probably an additional unknown amount of this activity that is undetected) because moving higher in the league tables might be deemed more important than getting students to reflect fairly on their experience of an institution as part of an enhancement exercise’. We noted two instances where it was suggested that universities may be encouraging students filling in the Survey to be positive about the institution. (House of Commons, 2009, para. 101)

Feedback to students

As well as feedback from students on their learning environment, it is important to provide students with feedback on their work and learning. This is different from completing the feedback loop, which is primarily about providing students with information on action that results from their feedback. Feedback to students on their work and the progress of their learning refers to the commentary that accompanies summative gradings or that guides students through formative assessment. In the United Kingdom, the Quality Assurance Agency’s (2009) Code of Practice, Part 6, refers to the assessment of students. Precept 12 of Part 6 of the Code states that: ‘Institutions should ensure that appropriate feedback is provided to students on assessed work in a way that promotes learning and facilitates improvement.’

Feedback to students on their learning and feedback from students on their experience are treated quite separately in many settings, when, in fact, there is potential for symbiosis. Feedback to students on the work they have done, if provided appropriately, helps them improve, gives them an idea of how they are progressing, aids motivation and empowers them as learners. Badly done, feedback to students can be confusing, misleading, demotivating and disempowering.

As long as feedback from students is perceived as some kind of consumer satisfaction, rather than as integral to a transformative learning context, feedback from students will be disengaged from feedback to students.

Before examining the symbiosis, there are a few observations on appropriate feedback to students on their learning. Feedback should be informative, which requires understandable explanations that are unambiguous and clear and not an exhibition of the tutor’s erudition. Students may not be as familiar with academic language, concepts and nuances as the lecturer may assume. Feedback should be structured, focused and consistent, as well as providing appropriate indications of relative progress. Importantly, for students, feedback needs to be provided promptly, closely following the hand-in date or event. Where the organisational structure makes this difficult, early feedback to the whole class on key points can be a valuable stopgap.

It is essential that feedback on assessed work clearly indicates how to improve, by providing specific detail on any misapprehensions in the student’s work and by making helpful suggestions on improvement of both particulars and of written or oral presentation style. Feedback sessions, of whatever type, need to be positive experiences even where there is bad news. Feedback on work should enhance self-esteem, not damage it; and so tutors need to be aware of the impact of their feedback and to be sure they take into account the wider context of the students’ lives.

Typical unhelpful feedback includes work that is returned with just a summative grade or comment, or is annotated with ticks and crosses but no commentary or explanation. Vague, general or confusing remarks, such as ‘explain’, ‘deconstruct’ or ‘isn’t this contentious?’ are unhelpful, as are subjective or idiosyncratic remarks, such as ‘Weber’s analysis is fatuous’.

The UK Parliamentary Select Committee report stated:

We note that the QAA produced a code of practice on the assessment of students … We are therefore surprised that feedback on students’ work is an issue of such concern … It is our view that, whether at the level of module, course, department or institution, students should be provided with more personalised information about the intended parameters of their own assessment experience. It is unacceptable and disheartening for any piece of work whether good, average or poor to be returned to a student with only a percentage mark and no comments or with feedback but after such a long time that the feedback is ineffective. (House of Commons, 2009: 85–6, emphasis in original)

The Committee thus concluded with a recommendation to Government to ensure a ‘code of practice on (i) the timing, (ii) the quantity, and (iii) the format and content of feedback and require higher education institutions to demonstrate how they are following the Code when providing feedback to students in receipt of support from the taxpayer’ (House of Commons, 2009: 86–7).

Skilled feedback is not something that comes naturally; it is a tricky interpersonal relationship and staff need to spend time developing feedback skills. In an attempt to improve feedback, the University of Cambridge, Department of Plant Sciences (2008), for example, used focus groups and questionnaires to examine student perceptions and found that many students thought they were not provided with enough useful feedback to help them improve. This concern was mirrored by supervisors, who felt unsure about how to provide effective formative feedback. The result was a workshop in which supervisors reviewed a list of comments made on different essays for the same student. They discussed the effectiveness of the different marking styles, which ranged from directive comments to just ticks and marks. Supervisors were also asked to examine a variety of exemplar essays that had all been awarded an upper-second grade and to discuss what would be worth commenting on, the strengths and weaknesses of the work, and how the essays could be improved. Such processes greatly enhance the efficacy of the process of feedback on student work.

All this suggests the importance of one-to-one feedback tutorials with student and staff. Ideally these should be face-to-face, but they might also be conducted virtually. Getting students to undertake a self-evaluation of the work they have undertaken, prior to a tutorial, is a useful way to explore how the student’s self-perception relates to the tutor assessment.

In essence, feedback to students should be empowering. It should result in tutor and student agreeing what is to be done to improve; enabling students to evaluate their own performance and diagnose their own strengths and weaknesses. This, incidentally, is aided by developing reflective skills in the curriculum so that students are themselves well prepared and motivated to make effective use of the feedback that is available. Naidoo (2005), in discussing the Student Satisfaction approach, argued that: ‘quality empowerment entails the concept of agency –- the ability not only to participate in but also to shape education. Empowered students have the ability not only to make the correct choices with regard to institutions and programmes, but also to play a positive role in promoting and enhancing quality of education processes and outcomes’ (p. 2).

Integrating feedback

Some of the most important criteria for quality, as specified by staff and students are: feedback on assessed work; fair assessment regimes; and clear assessment criteria. Feedback from students for continuous improvement processes should mesh with the processes for feedback to students about academic performance. However, as institutions collect more information from students about the service they receive, there is evidence of less formative feedback to students about their own academic, professional and intellectual development. This is in part because individual interaction between tutor and student is decreasing, or in some systems continues to be virtually non-existent.

There are ways to ensure a symbiosis between feedback from and feedback to students but this requires two things: a commitment to enabling learning; and recognition that feedback from students is not a consumerist reaction but integral to their own transformative learning. Thus, it is vital to ensure that feedback from students is about their learning and skill development rather than the performance of teachers. It is also important to create space for discussion tutorials in which both student perception of their learning experience and staff evaluation of the student’s progress are openly discussed without prejudice. This will not only change the emphasis on learning (away from lectures, for example) but also implies a shift in the balance of power in the learning relationship. A critical dialogue replaces a unidirectional exertion of intellectual dominance.

Conclusions

Student feedback on their learning is one of the most effective tools in the ongoing improvement of the quality of higher education. It is not the only tool and should never be used as the only source of evidence in making changes. However, it is potentially a powerful force in guiding improvement, providing the data collection and analysis is effective, addresses the important issues, engages with the student learning experience and is acted upon in a timely manner.

Students are key stakeholders in the quality monitoring and assessment processes and it is important to obtain their views. However, as James and McInnis (1997) argued over a decade ago, one should have ‘multiple strategies for student feedback’ (p. 105). It is crucial to attach significance to informal feedback and not be beguiled by formal feedback mechanisms, which in the main are limited and lack fine distinction.

Far too many approaches to student feedback start by designing a questionnaire rather than exploring the purpose of student feedback. The consumerist view predominates in such method-led approaches, which, in the main, merely act as a public relations exercise or an indicator of accountability rather than as a real engagement with the student perspective. A clear analysis of the purpose and use of student feedback, a structure for implementing and communicating changes designed to improve the student learning experience, as well as a clear linkage between feedback from and feedback to students on their learning and progress, are essential if student feedback is to be more than a cosmetic exercise.

References

Astin, A.W. Why not try some new ways of measuring quality? Educational Record. 1982; 63(2):10–15.

Attwood, R., Probe ordered into “manipulation”, 2008.. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=26andstorycode=400809 [Times Higher Education, 28 February 2008. Available online at:, (accessed 5 January 2010).].

Ballantyne, C., Improving university teaching: giving feedback to students. R. Pospisil, L. Willcoxson. Learning Through Teaching, Proceedings of the 6th Annual Teaching Learning Forum. Murdoch University, Perth, 1997:12–15.

Baxter, P.E. The TEVAL experience 1983–1988: the impact of a student evaluation of teaching scheme on university teachers. Studies in Higher Education. 1991; 16:151–178.

Carr, S., Hamilton, E., Meade, P. Is it possible? Investigating the influence of external quality audit on university performance. Quality in Higher Education. 2005; 11(3):195–221.

Church, F., Students as consumers: the importance of student feedback in the quality assurance process, 2008.. http://www.ukcle.ac.uk/interact/lili/2001/church.html [The UK Centre for Legal Education. Available online at:, (accessed 10 January 2010).].

Douglas, J., Douglas, A. Evaluating teaching quality. Quality in Higher Education. 2006; 12(1):3–13.

Ewell, P. A preliminary study of the feasibility and utility for national policy of instructional ‘good practice’ indicators in undergraduate education. Boulder, CO: NCHEMS; 1993. [Report prepared for the National Center for Education Statistics, mimeo].

Furedi, F. iPod for their thoughts?, 2008. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=26&storycode=402162 [Times Higher Education, 29 May 2008. Available online at:, (accessed 15 January 2010).].

Harvey, L., Getting student satisfaction, 2001.. http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2001/nov/27/students [Guardian, 27 November. Online. Available online at:, (accessed 16 January 2010).].

Harvey, L., Associates. Student Satisfaction Manual. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997.

Hill, R. A European student perspective on quality. Quality in Higher Education. 1995; 1(1):67–75.

Horsburgh, M. Quality monitoring in two institutions: a comparison. Quality in Higher Education. 1998; 4(2):115.

House of Commons, Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee. Students and Universities: Eleventh Report of Session 2008–09; Volume I. The Stationery Office, London, 2009.

James, R., Mclnnis, C. Coursework masters degrees and quality assurance: implicit and explicit factors at programme level. Quality in Higher Education. 1997; 3(2):101–112.

Jones, S. Measuring the quality of higher education: linking teaching quality measures at the delivery level to administrative measures at the university level. Quality in Higher Education. 2003; 9(3):223–229.

Kane, D., Williams, J., Cappuccini-Ansfield, G. Student satisfaction surveys: the value in taking an historical perspective. Quality in Higher Education. 2008; 14(2):135–155.

Leckey, J., Neill, N. Quantifying quality: the importance of student feedback. Quality in Higher Education. 2001; 7(1):19–32.

Lomas, L., Nicholls, G. Enhancing teaching quality through peer review of teaching. Quality in Higher Education. 2005; 11(2):137–149.

Marsh, H.W., Roche, L. The use of students’ evaluations and an individually structured intervention to enhance university teaching effectiveness. American Educational Research Journal. 1993; 30:217–251.

Massy, W.F., French, N.J. Teaching and Learning Quality Process Review: what the programme has achieved in Hong Kong. Quality in Higher Education. 2001; 7(1):33–45.

Mazelan, P., Brannigan, C., Green, D., Tormey, P. Report on the 1992 Survey of Student Satisfaction with their Educational Experience at UCE. Birmingham: Student Satisfaction Research Unit, University of Central England; 1992.

Mostrous, A., Kingston University students told to lie to boost college’s rank in government poll. The Times. 2008. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article3924417.ece [14 May 2008. Available online at:, (accessed 15 January 2010).].

Naidoo, P., Student Literacy and Empowerment, 2005.. http://www.che.ac.za/documents/d000110/Student_Quality_Literacy_Naidoo_2005.pdf [Online. Available at:, (accessed 16 January 2010)].

Palermo, J., Closing the loop on student evaluations, 2004.. http://www.aair.org.au/jir/2004Papers/PALERM0.pdf [Available onlilne at:, (accessed 16 January 2010)].

Powney, J., Hall, S. Closing the loop: the impact of student feedback on students’ subsequent learning. Edinburgh: Scottish Council for Research in Education; 1998.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA), Code of Practice, 2009.. http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/codeOfPractice/default.asp [Available online at:, (accessed 15 January 2010).].

Rowley, J. Measuring quality in higher education. Quality in Higher Education. 1996; 2(3):237–255.

Swain, H., A hotchpotch of subjectivity: the National Student Survey was a key indicator in the Guardian’s university league tables. But is it fair? The Guardian. 2009. [19 May 2009.].

Torper, U.Studentbarometern, Resultatredovisning [The Student Barometer, Documentation of Results]. Lund: Lunds Universitet, Utvarderingsenheten, 1997. [Report No. 97:200.].

University of Cambridge, Department of Plant Sciences, Feedback to students in the Department of Plant Sciences, 2008.. http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/offices/education/lts/lunch/lunch14.html [Report. Available online at:, (accessed 16 January 2010).].

Walker-Garvin, A. (undated). Unsatisfactory Satisfaction: Student Feedback and Closing the Loop. Quality Promotion and Assurance. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Watson, S. Closing the feedback loop: ensuring effective action from student feedback. Tertiary Education and Management. 2003; 9:145–157.

Williams, J., Student satisfaction: a British model of effective use of student feedback in quality assurance and enhancement. Paper presented at the 14th International Conference on assessment and Quality in Higher Education, Vienna, 24–27 July, 2002.

Williams, J., Cappuccini-Ansfield, G. Fitness for purpose? National and institutional approaches to publicising the student voice. Quality in Higher Education. 2007; 13(2):159–172.

Yorke, M. Siamese Twins? Performance indicators in the service of accountability and enhancement. Quality in Higher Education. 1995; 1(1):13–30.

1Since the change of name (and senior management team) the uniqueness of the UCE approach and the enormous value that it had for the university has been lost.

2In some institutions programmes of study are referred to as ‘courses’ or ‘pathways’. However, ‘course’ is a term used in some institutions to mean ‘module’ or ‘unit’ of study, that is, a sub-element of a programme of study. Due to the ambiguity of ‘course’, the terms ‘programme of study’ and ‘module’ will be used in this chapter.