1

Hello Blazor

Thank you for picking up your copy of Web Development with Blazor. This book intends to get you started as quickly and pain-free as possible, chapter by chapter, without you having to read this book from cover to cover before getting your Blazor on.

This book will start by guiding you through the most common scenarios you’ll come across when you start your journey with Blazor and will also dive into a few more advanced scenarios. This book aims to show you what Blazor is – both Blazor Server, Blazor WebAssembly, and Blazor Hybrid – how it all works practically and to help you avoid traps.

This is the book’s second edition; much has happened since the first edition. .NET 6 and .NET 7 got released, and in this revision, I have updated the content to reflect the changes and the new functionality we got. Not only that, I have simplified the demos in the book, giving even more focus on Blazor and removing things that aren’t directly Blazor (like Entity Framework).

A common belief is that Blazor is WebAssembly, but WebAssembly is just one way of running Blazor. Many books, workshops, and blog posts on Blazor focus heavily on WebAssembly. This book will cover Blazor WebAssembly, Blazor Server, and Blazor Hybrid. There are a few differences between Blazor Server and Blazor WebAssembly; I will point them out as we go along.

This first chapter will explore where Blazor came from, what technologies made Blazor possible, and the different ways of running Blazor. We will also touch on which type is best for you.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

- Why Blazor?

- Preceding Blazor

- Introducing WebAssembly

- Introducing .NET 7

- Introducing Blazor

Technical requirements

It is recommended that you have some knowledge of .NET before you start, as this book is aimed at .NET developers who want to utilize their skills to make interactive web applications. However, it’s more than possible that you will pick up a few .NET tricks along the way if you are new to the world of .NET.

Why Blazor?

Not that long ago, I got asked by a random person on Facebook if I was working with Blazor.

I said: Yes, yes I do.

He then continued with a long remark telling me that Blazor would never beat Angular, React, or Vue.

I see these kinds of remarks quite often, and it’s essential to understand that beating other SPA frameworks has never been the goal. This is not Highlander, and there can be more than one.

Learning web development has previously been pretty tough. Not only do we need to know ASP.NET for the server, but we also need to learn a SPA framework like React, Angular, or VUE.

But it doesn’t end there. We also need to learn NPM, Bower, and Parcel, as well as JavaScript or TypeScript.

We need to understand transpiling and build that into our development pipeline. This is, of course, just the tip of the iceberg; depending on technology, we need to explore other rabbit holes.

Blazor is an excellent choice for .NET developers to write interactive web applications without needing to learn (or keep up with) all the things we just mentioned. We can leverage our existing C# knowledge and the packages we are used to and share code between server and client.

I usually say: “Blazor removes all the things I hate about web development.” To be honest, I guess the saying should be, “Blazor can remove all the things I hate about web development.” With Blazor, it is still possible to do JavaScript interop and use JavaScript frameworks or other SPA frameworks from within Blazor, but we don’t have to.

Blazor has opened a door where I can feel productive, creating a great user experience for my users using my existing C# knowledge.

Preceding Blazor

You probably didn’t get this book to read about JavaScript, but it helps to remember that we are coming from a pre-Blazor time. I recall that time – the dark times. Many of the concepts used in Blazor are not that far from those used in many JavaScript frameworks, so I will start with a brief overview of our challenges.

As developers, we have many different platforms we can develop for, including desktop, mobile, games, the cloud (or server-side), AI, and even IoT. All these platforms have a lot of different languages to choose from, but there is, of course, one more platform: the apps that run inside the browser.

I have been a web developer for a long time, and I’ve seen code move from the server to run within the browser. It has changed the way we develop our apps. Frameworks such as Angular, React, Aurelia, and Vue have changed the web from reloading the whole page to updating small parts on the fly. This new on-the-fly update method has enabled pages to load quicker, as the perceived load time has been lowered (not necessarily the whole page load).

But for many developers, this is an entirely new skill set; that is, switching between a server (most likely C#, if you are reading this book) to a frontend developed in JavaScript. Data objects are written in C# in the backend and then serialized into JSON, sent via an API, and then deserialized into another object written in JavaScript in the frontend.

JavaScript used to work differently in different browsers, which jQuery tried to solve by having a common API that was translated into something the web browser could understand. Now, the differences between different web browsers are much smaller, which has rendered jQuery obsolete in many cases.

JavaScript differs slightly from other languages since it is not object-oriented or typed, for example. In 2010, Anders Hejlsberg (known for being C#, Delphi, and Turbo Pascal’s original language designer) started working on TypeScript. This object-oriented language can be compiled/transpiled into JavaScript.

You can use Typescript with Angular, React, Aurelia, and Vue, but in the end, it is JavaScript that will run the actual code. Simply put, to create interactive web applications today using JavaScript/TypeScript, you need to switch between languages and choose and keep up with different frameworks.

In this book, we will look at this in another way. Even though we will talk about JavaScript, our primary focus will be developing interactive web applications mainly using C#.

Now, we know a bit about the history of JavaScript. JavaScript is no longer the only language that can run within a browser, thanks to WebAssembly, which we will cover in the next section.

Introducing WebAssembly

In this section, we will look at how WebAssembly works. One way of running Blazor is by using WebAssembly, but for now, let’s focus on what WebAssembly is.

WebAssembly is a binary instruction format that is compiled and, therefore, smaller. It is designed for native speeds, which means that when it comes to speed, it is closer to C++ than it is to JavaScript. When loading JavaScript, the JavaScript files (or inline) are downloaded, parsed, optimized, and JIT-compiled; most of those steps are not needed for WebAssembly.

WebAssembly has a very strict security model that protects users from buggy or malicious code. It runs within a sandbox and cannot escape that sandbox without going through the appropriate APIs. Suppose you want to communicate outside WebAssembly, for example, by changing the Document Object Model (DOM) or downloading a file from the web. In that case, you will need to do that with JavaScript interop (more on that later, and don’t worry – Blazor will solve this for us).

Let’s look at some code to get a bit more familiar with WebAssembly.

In this section, we will create an app that sums two numbers and returns the result, written in C (to be honest, this is about the level of C I’m comfortable with).

We can compile C into WebAssembly in a few easy steps:

- Navigate to https://wasdk.github.io/WasmFiddle/.

- Add the following code:

int main() { return 1+2; } - Press Build and then Run.

You will see the number 3 being displayed in the output window toward the bottom of the page, as shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 1.1: WasmFiddle

WebAssembly is a stack machine language, which means that it uses a stack to perform its operations.

Consider this code:

1+2

Most compilers (including the one we just used) will optimize the code and return 3.

But let’s assume that all the instructions should be executed. This is the way WebAssembly would do things:

- It will start by pushing

1onto the stack (instruction: i32.const 1), followed by pushing2onto the stack (instruction: i32.const 2). At this point, the stack contains1and2. - Then, we must execute the add-instruction (

i32.add), which will pop (get) the two top values (1and2) from the stack, add them up, and push the new value onto the stack (3).

This demo shows that we can build WebAssembly from C code. Now, we have C code that’s been compiled into WebAssembly running in our browser.

OTHER LANGUAGES

Generally, it is only low-level languages that can be compiled into WebAssembly (such as C or Rust). However, there are a plethora of languages that can run on top of WebAssembly. Here is a great collection of some of these languages: https://github.com/appcypher/awesome-wasm-langs.

WebAssembly is super performant (near-native speeds) – so performant that game engines have already adapted this technology for that very reason. Unity, as well as Unreal Engine, can be compiled into WebAssembly.

Here are a couple of examples of games running on top of WebAssembly:

- Angry Bots (Unity): https://beta.unity3d.com/jonas/AngryBots/

- Doom: https://wasm.continuation-labs.com/d3demo/

This is a great list of different WebAssembly projects: https://github.com/mbasso/awesome-wasm.

This section touched the surface of how WebAssembly works; in most cases, you won’t need to know much more. We will dive into how Blazor uses this technology later in this chapter.

To write Blazor apps, we must leverage the power of .NET 7, which we’ll look at next.

Introducing .NET 7

The .NET team has been working hard on tightening everything up for us developers for years. They have been making everything simpler, smaller, cross-platform, and open source – not to mention easier to utilize your existing knowledge of .NET development.

.NET core was a step toward a more unified .NET. It allowed Microsoft to reenvision the whole .NET platform and build it in a completely new way.

There are three different types of .NET runtimes:

- .NET Framework (full .NET)

- .NET Core

- Mono/Xamarin

Different runtimes had different capabilities and performances. This also meant that creating a .NET core app (for example) had different tooling and frameworks that needed to be installed.

.NET 5 is the start of our journey toward one single .NET. With this unified toolchain, the experience to create, run, and so on will be the same across all the different project types. .NET 5 is still modular in a similar way that we are used to, so we do not have to worry that merging all the different .NET versions is going to result in a bloated .NET.

Thanks to the .NET platform, you will be able to reach all the platforms we talked about at the beginning of this chapter (web, desktop, mobile, games, the cloud (or server-side), AI, and even IoT) using only C# and with the same tooling.

Blazor has been around for a while now. In .NET Core 3, the first version of Blazor Server was released, and at Microsoft Build in 2020, Microsoft released Blazor WebAssembly.

In .NET 5, we got a lot of new components for Blazor, pre-rendering, and CSS Isolation to name a few things. Don’t worry; we will go through all these things throughout the book.

In .NET 6, we got even more functionality like Hot Reload, co-located JavaScript, new components, and much more, all of which we will explore throughout the book.

In November 2022, Microsoft released .NET 7, which has even more enhancements for Blazor developers.

Looking at the enhancements and number of features, I can only conclude that Microsoft believes in Blazor, and so do I.

Now that you know about some of the surrounding technologies, in the next section, it’s time to introduce the main character of this book: Blazor.

Introducing Blazor

Blazor is an open-source web UI SPA framework. That’s a lot of buzzwords in the same sentence, but simply put, it means that you can create interactive SPA web applications using HTML, CSS, and C# with full support for bindings, events, forms and validation, dependency injection, debugging, and much more. We will take a look at these in this book.

In 2017, Steve Sanderson (well-known for creating the Knockout JavaScript framework and who works for the ASP.NET team at Microsoft) was about to do a session called Web Apps can’t really do *that*, can they? at the developer conference NDC Oslo.

But Steve wanted to show a cool demo, so he thought, would it be possible to run C# in WebAssembly? He found an old inactive project on GitHub called Dot Net Anywhere, which was written in C and used tools (similar to what we just did) to compile the C code into WebAssembly.

He got a simple console app running inside the browser. This would have been a fantastic demo for most people, but Steve wanted to take it further. He thought, is it possible to create a simple web framework on top of this?, and went on to see if he could get the tooling working as well.

When it was time for his session, he had a working sample to create a new project, create a todo-list with great tooling support, and run the project inside the browser.

Damian Edwards (the .NET team) and David Fowler (the .NET team) were also at the NDC conferences. Steve showed them what he was about to demo, and they described the event as their heads exploded and their jaws dropped.

And that’s how the prototype of Blazor came into existence.

The name Blazor comes from a combination of Browser and Razor (which is the technology used to combine code and HTML). Adding an L made the name sound better, but other than that, it has no real meaning or acronym.

There are a couple of different flavors of Blazor, including Blazor Server, Blazor WebAssembly, Blazor Hybrid (using .NET MAUI).

There are some pros and cons of the different versions, all of which I will cover in the upcoming sections and chapters.

Blazor Server

Blazor Server uses SignalR to communicate between the client and the server, as shown in the following diagram:

Figure 1.2: Overview of Blazor Server

SignalR is an open-source, real-time communication library that will create a connection between the client and the server. SignalR can use many different means of transporting data and automatically select the best transport protocol based on your server and client capabilities. SignalR will always try to use WebSockets, which is a transport protocol built into HTML5. If WebSockets is not enabled, it will gracefully fall back to another protocol.

Blazor is built with reusable UI elements called components (more on components in Chapter 4, Understanding Basic Blazor Components). Each component contains C# code, and markup and can even include another component. You can use Razor syntax to mix markup and C# code or do everything in C# if you wish. The components can be updated by user interaction (pressing a button) or triggers (such as a timer).

The components are rendered into a render tree, a binary representation of the DOM containing object states and any properties or values. The render tree will keep track of any changes compared to the previous render tree, and then send only the things that changed over SignalR using a binary format to update the DOM.

JavaScript will receive the changes on the client-side and update the page accordingly. If we compare this to traditional ASP.NET, we only render the component itself, not the entire page, and we only send over the actual changes to the DOM, not the whole page.

There are, of course, some disadvantages to Blazor Server:

- You need to always be connected to the server since the rendering is done on the server. If you have a bad internet connection, the site might not work. The big difference compared to a non-Blazor Server site is that a non-Blazor Server site can deliver a page and then disconnect until it requests another page. With Blazor, that connection (SignalR) must always be connected (minor disconnections are ok).

- There is no offline/PWA mode since it needs to be connected.

- Every click or page update must do a round trip to the server, which might result in higher latency. It is important to remember that Blazor Server will only send the changed data. I have not experienced any slow response times.

- Since we have to have a connection to the server, the load on that server increases and makes scaling difficult. To solve this problem, you can use the Azure SignalR hub to handle the constant connections and let your server concentrate on delivering content.

- Each connection stores the information in the server’s memory, increasing memory use and making load balancing more difficult.

- To be able to run it, you have to host it on an ASP.NET Core-enabled server.

However, there are advantages to Blazor Server as well:

- It contains just enough code to establish that the connection is downloaded to the client, so the site has a small footprint, which makes the site startup really fast

- Since everything is rendered on the server, Blazor server is more SEO friendly.

- Since we are running on the server, the app can fully utilize the server’s capabilities.

- The site will work on older web browsers that don’t support WebAssembly.

- The code runs on the server and stays on the server; there is no way to decompile the code.

- Since the code is executed on your server (or in the cloud), you can make direct calls to services and databases within your organization.

At my workplace, we already had a large site, so we decided to use Blazor Server for our projects. We had a customer portal and an internal CRM tool, and our approach was to take one component at a time and convert it into a Blazor component.

We quickly realized that, in most cases, it was faster to remake the component in Blazor rather than continue to use ASP.NET MVC and add functionality. The User Experience (UX) for the end-user became even better as we converted.

The pages loaded faster. We could reload parts of the page as we needed instead of the whole page, and so on.

We found that Blazor introduced a new problem: the pages became too fast. Our users didn’t understand if data had been saved because nothing happened; things did happen, but too fast for the users to notice. Suddenly, we had to think more about UX and how to inform the user that something had changed. This is, of course, a very positive side effect from Blazor.

Blazor Server is not the only way to run Blazor – you can also run it on the client (in the web browser) using WebAssembly.

Blazor WebAssembly

There is another option: instead of running Blazor on a server, you can run it inside your web browser using WebAssembly.

Microsoft has taken the mono runtime (which is written in C) and compiled that into WebAssembly.

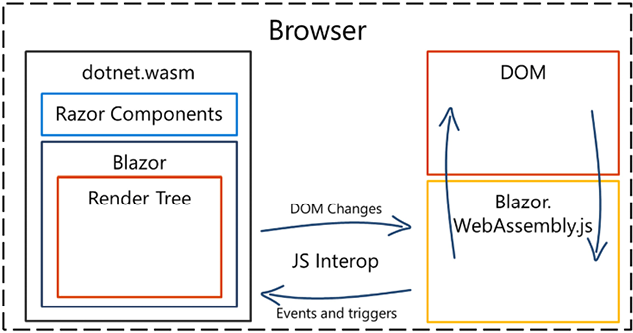

The WebAssembly version of Blazor works very similarly to the server version, as shown in the following diagram. We have moved everything off the server, and it is now running within our web browser:

Figure 1.3: Overview of Blazor WebAssembly

A render tree is still created, and instead of running the Razor pages on the server, they are now running inside our web browser. Instead of SignalR, since WebAssembly doesn’t have direct DOM access, Blazor updates the DOM with direct JavaScript interop.

The mono runtime that’s compiled into WebAssembly is called dotnet.wasm. The page contains a small piece of JavaScript that will make sure to load dotnet.wasm. Then, it will download blazor.boot.json, a JSON file containing all the files the application needs to run, as well as the application’s entry point.

If we look at the default sample site that is created when we start a new Blazor project in Visual Studio, the Blazor.boot.json file contains 63 dependencies that need to be downloaded. All the dependencies get downloaded and the app boots up.

As we mentioned previously, dotnet.wasm is the mono runtime that’s compiled into WebAssembly. It runs .NET DLLs – the ones you have written and the ones from .NET Framework (which is needed to run your app) – inside your browser.

When I first heard of this, I got a bit of a bad taste. It’s running the whole .NET runtime inside my browser?! But then, after a while, I realized how amazing that is. You can run any .NET Standard DLLs in your web browser.

In the next chapter, we will look at exactly what happens and in what order code gets executed when a WebAssembly app boots up.

The big concern is the download size of the site. The simple file new sample app is about 1.3 MB, which is quite large if you put a lot of effort into the download size. What you should remember, though, is that this is more like a Single-Page Application (SPA) – it is the whole site that has been downloaded to the client. I compared the size to some well-known sites on the internet; I then only included the JavaScript files for these sites but also included all the DLLs and JavaScript files for Blazor.

The following is a diagram of my findings:

Figure 1.4: JavaScript download size for popular sites

Even though the other sites are larger than the sample Blazor site, you should remember that the Blazor DLLs are compiled and should take up less space than a JavaScript file. WebAssembly is also faster than JavaScript.

There are some disadvantages to Blazor WebAssembly:

- Even if we compare it to other large sites, the footprint of a Blazor WebAssembly is large and there are a large number of files to download.

- To access any on-site resources, you will need to create a Web API to access them. You cannot access the database directly.

- The code is running in the browser, meaning it can be decompiled. This is something all app developers are used to, but it is perhaps not as common for web developers.

There are, of course, some advantages of Blazor WebAssembly as well:

- Since the code runs in the browser, creating a Progressive Web App (PWA) is easy.

- Does not require a connection to the server. It will work offline.

- Since we’re not running anything on the server, we can use any backend server or file share (no need for a .NET-compatible server in the backend).

- No round trips mean that you can update the screen faster (that is why there are game engines that use WebAssembly).

I wanted to put that last advantage to the test! When I was seven years old, I got my first computer, a Sinclair ZX Spectrum. I remember that I sat down and wrote the following:

10 PRINT "Jimmy"

20 GOTO 10

That was my code; I made the computer write my name on the screen over and over!

That was when I decided that I wanted to become a developer to make computers do stuff.

After becoming a developer, I wanted to revisit my childhood and decided I wanted to build a ZX Spectrum emulator. In many ways, the emulator has become my test project instead of a simple Hello World when I encounter new technology. I’ve had it running on a Gadgeteer, Xbox One, and even a HoloLens (to name a few).

But is it possible to run my emulator in Blazor?

It took me only a couple of hours to get the emulator working with Blazor WebAssembly by leveraging my already built .NET Standard DLL; I only had to write the code specific to this implementation, such as the keyboard and graphics. This is one of the reasons Blazor (both Server and WebAssembly) is so powerful: it can run libraries that have already been made. Not only can you leverage your knowledge of C#, but you can also take advantage of the large ecosystem and .NET community.

You can find the emulator here: http://zxbox.com. This is one of my favorite projects to work on, as I keep finding ways to optimize and improve the emulator.

Building this type of web application used to only be possible with JavaScript. Now, we know we can use Blazor WebAssembly and Blazor Server, but which one of these new options is the best?

Blazor WebAssembly versus Blazor Server

Which one should we choose? The answer is, as always, it depends. You have seen the advantages and disadvantages of both.

If you have a current site that you want to port over to Blazor, I recommend going for the server side; once you have ported it, you can make a new decision as to whether you want to go for WebAssembly as well. This way, it is easy to port parts of the site, and the debugging experience is better with Blazor Server.

Suppose your site runs on a mobile browser or another unreliable internet connection. In that case, you might consider going for an offline-capable (PWA) scenario with Blazor WebAssembly since Blazor Server needs a constant connection.

The startup time for WebAssembly is a bit slow, but there are ways to combine the two hosting models to have the best of two worlds. We will cover this in Chapter 16, Going Deeper into WebAssembly.

There is no silver bullet when it comes to this question, but read up on the advantages and disadvantages and see how those affect your project and use cases.

We can run Blazor server-side and on the client, but what about desktop and mobile apps?

Blazor Hybrid / .NET MAUI

.NET MAUI is a cross-platform application framework. The name comes from .NET Multi-platform App UI and is the next version of Xamarin. We can use traditional XAML code to create our cross-platform application just as with Xamarin however, .NET MAUI also targets desktop operating systems that will make it possible to run our Blazor app on Windows and even macOS.

Using Blazor Hybrid, we also get access to native APIs (not only Web APIs), which makes it possible for us to take our application to another level.

We will take a look at .NET MAUI in Chapter 18, Visiting .NET MAUI.

As you can see, there are a lot of things you can do with Blazor, and this is just the beginning.

Summary

In this chapter, you were provided with an overview of the different technologies you can use with Blazor, such as server-side (Blazor Server), client-side (WebAssembly), desktop, and mobile. This overview should have helped you decide what technology to choose for your next project.

We then discussed how Blazor was created and its underlying technologies, such as SignalR and WebAssembly. You also learned about the render tree and how the DOM gets updated to give you an understanding of how Blazor works under the hood.

In the upcoming chapters, I will walk you through various scenarios to equip you with the knowledge to handle everything from upgrading an old/existing site, and creating a new server-side site, to creating a new WebAssembly site.

We’ll get our hands dirty in the next chapter by configuring our development environment and creating and examining our first Blazor App.

Further reading

As a .NET developer, you might be interested in the Uno Platform (https://platform.uno/), which makes it possible to create a UI in XAML and deploy it to many different platforms, including WebAssembly.

If you want to see how the ZX Spectrum emulator is built, you can download the source code here: https://github.com/EngstromJimmy/ZXSpectrum.

Join our community on Discord

Join our community’s Discord space for discussions with the author and other readers:

https://packt.link/WebDevBlazor2e