Even if business cycles never existed, managing a business successfully is challenging. These challenges include competition, changing consumer preferences, input price pressures, selling prices, cash flow issues, employee morale, strikes, taxes, regulations, geopolitical events, natural disasters, quality control, and of course supply chain disruptions. In other words, entrepreneurs should be thinking of value networks that will allow them to switch out links, take new routes from supplier to market, and be agile and flexible. Business is a constant swirling flow of change and more change.1 And in 2020, COVID-19 caused the greatest challenge to American businesses—large and small—possibly in our country’s history as many states and cities locked down “nonessential” businesses for weeks or months and then imposed draconian restrictions as they slowly allowed restaurants, gyms, hair salons, and small shops to reopen. During 2020, 29 retailers declared bankruptcy, including such iconic retailers such as JCPenney, Lord & Taylor, Neiman Marcus, and Brooks Brothers.2 And thousands of small businesses have closed their doors permanently.

And during the 2007–2009 Great Recession, retailers that filed for bankruptcy or liquidated their businesses included, Chrysler, GM, KB Toys, Circuit City, CompUSA, Linens ’N Things, Fortunoff, Levitz, and Bombay, while other retail outlets reduced the number of brick-andmortar stores.3

A successful business where “all cylinders” are working smoothly will no doubt be profitable and sustainable. If one or more of a business’ cylinders is underperforming, then the enterprise could not only suffer losses but its survival could also be in jeopardy. The business cycle, however, adds another dimension that poses a huge challenge to managing a business. Just when it appears that a company is firing on all cylinders, the bump in the road—a major economic decline (the bust phase of the cycle)—could turn profits into losses and could jeopardize a business’ very survival.

Thus, the U.S. economy is in reality multidimensional. We have the “real” economy based upon savings, investment, consumer preferences, and international trade; in other words, the voluntary choices of buyers and sellers that create the economy’s mosaic of goods and services valued by consumers. Imposed on the economy is the business cycle, which we have seen is “man-made” and manifests itself in distorting the structure of production leading to unsustainable booms and painful busts. Consequently, the supply chain would be affected from raw materials to consumer sales during the business cycle. An overview, therefore, of the business cycle and the supply chain would provide managers with insights on how to best manage their enterprises no matter where their business is in the structure of production.

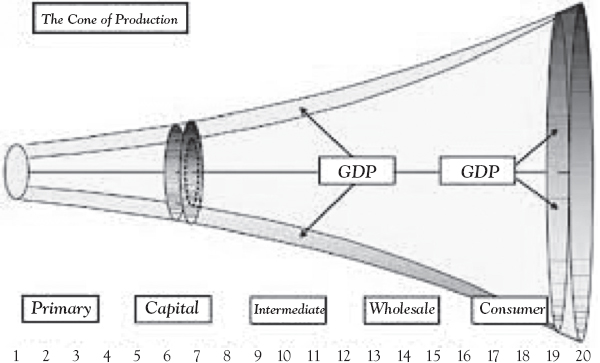

One template of viewing the economy is based on Sean Corrigan’s cone of production (see Figure 5.1).4 Over time, primary (raw) materials, mixed with capital become intermediate goods, which are then distributed to wholesalers and eventually to consumers. Essentially, this is the flow of goods in the free market economy. In short, we can trace the roots of every consumer good back to its “state of nature” and then follow its journey as these raw materials are eventually transformed into retail products that are purchased in stores or online. In other words, virtually all the challenges cited at the beginning of the chapter must be addressed continuously for all firms to be profitable. Inasmuch as in a growing market economy, profits are more prevalent than losses, and the entrepreneurs/ managers who are the most adept in organizing their businesses will be the most successful.

Figure 5.1 The cone of production

Source: Sean Corrigan’s “Cone of Production,” https://mises.org/library/cone-production

All final sales comprise the nation’s GDP. A major shortcoming of GDP is that it fails to capture the enormous business-to-business (B2B) transactions throughout all stages of production before products reach the consumer.5 B2B sales comprise all the economic activity throughout the “structure of production”—the stages through which goods flow from raw materials to eventually becoming consumer goods. For example, the production of a pencil, a “low tech” product, requires billions of dollars of investment in forests, saw mills, petrochemical plants, mining, rubber plantations, transportation equipment, and so on.6 In other words, the “stuff” necessary to make a consumer product requires an extensive array—and co-ordination—of goods and services to bring a simple good as a pencil to retailers. The pencil supply chain is thus global and far-reaching.

Our task here is more “micro” oriented, namely, how managers can recognize an impending economic downturn in order to avoid suffering losses to stay afloat and thrive. By avoiding losses, or at least keeping them to a minimum, a business can come out of recession in a much better position than when the economy rolled over.

The cone of production, which is synonymous with the structure of production, and is a proxy for the supply chain. How is the supply chain affected during the business cycle? Supply chain management and business cycles were the subject of a research note by Heng et al. in 2005.7 The authors cite the work of economists, other academics, and practitioners who focused their attention on inventory fluctuations as the driving force generating business cycles. The so-called acceleration principle is thus responsible for the business cycle; namely, a burst of investment in inventory and capital goods leads to excessive inventories and thus trigger an eventual downturn in the economy.8 Although the role of monetary policy as the transmission mechanism for the business cycle is acknowledged, the authors cite the work of Ramey who concludes that demand for inventory is foremost in understanding the business cycle.9 In other words, the proponents of the acceleration principle describe where the distortions in the economy primarily occur and disregard the monetary factors, that is, easy money policies of the Federal Reserve, which set into motion the “excesses” that unfold during the business cycle.

Timing the end of the boom and the beginning of the subsequent recession is always fraught with error. If managers are too cautious during the boom, they will miss out on potential profits. On the other hand, if they were too optimistic as the boom unfolds and expand their capacity and production, the ensuing recession would reveal the errors they made. So what should managers do in general during the course of the business cycle?

One of the most common phenomena during the upswing in the business cycle especially in the later stages is that prices begin to rise as the Fed’s monetary inflation that began during the recession to stimulate the economy diffuses throughout the structure of production and provides the fuel for entrepreneurs to raise prices. This poses a particular challenge to managers, namely how much of these rising costs can be passed on to the next stage in the cone of production without losing sales or reducing the quality of their output to keep prices in check. Another factor to deal with is higher labor costs as employers scramble to find qualified employees to fill new positions or replace workers who have left because of retirement or have found other positions. Several strategies to deal with higher inflation include “building strong supplier relationships, inventory management, identifying demand forecasts of products/services, identify long-term production strategies and reaching out to both upstream and downstream suppliers among others.”10 Managers should assess what strategies to pursue depending on a company’s position in the cone of production and which specific approaches to pursue to dampen the impact of inflation on the business’ output and inputs.

At the end of 2020, commodity prices were on an upswing after a decline in the previous two years. The collapse in price of crude oil by more than two-thirds from 2014 to 2016 had a major impact on the commodity index. The uptrend in the price of crude oil at the end of 2020 was then a major factor in the overall commodity price index rising at that time. How long this trend continues remains to be seen during this cycle. In the meantime what will be the impacts on the supply chain will have to be assessed by managers if they do not take pre-emptive actions, as a commodity boom is underway to avoid the “squeeze” of higher input prices. In short, higher input prices can erode profit margins markedly and thus cause issues with suppliers who are also trying to maintain their margins.11

Raw Materials

Just as commerce is the lifeblood of civilization, raw materials are the lifeblood of the supply chain and the production process. From copper, lumber, iron ore, crude oil, rare earth minerals, and dozens of other commodities, which must be extracted from the earth, the producers of raw materials as well as the consumers of the resources that nature provides must work harmoniously for the supply chain to operate smoothly. Suppliers of raw materials are subject to environmental regulations, volatile prices, labor strikes, competitive pressures, domestic and global logistical challenges, and of course the business cycle. In other words, the challenges facing raw material producers are formidable. Nevertheless, without raw materials, civilization ceases to exist, as we know it.

Raw materials can be divided into two categories—direct materials, which is self-explanatory, and indirect materials, the supplies necessary to bring the raw materials to the marketplace.12 All direct and indirect materials, therefore, must be part of the planning process to calculate the costs of production. In addition, “in many cases, while it is always better to calculate than to predict, materials planning may include forecasting due to seasonality, market volatility or other external factors” (emphasis added).13 One of the primary external factors is the business cycle, which has a profound impact on the raw materials supply chain.

With the supply chain having gone global the past several decades, factors such as lead time, mode of production, long/short supply chain legs, overstocking and understocking, and quality and compliance issues all weigh on managers’ ability to optimize the raw materials supply chain.14

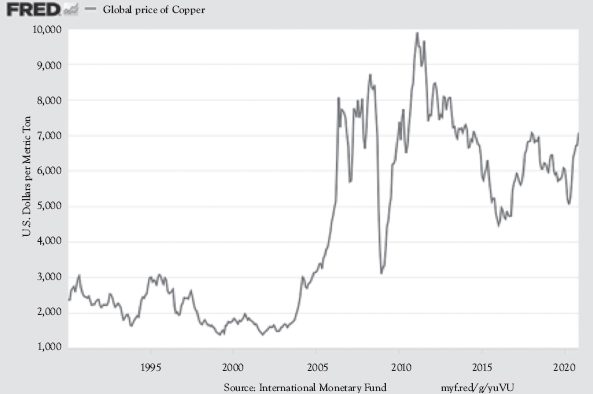

One of the greatest challenges that face raw materials managers is relying on optimistic forecasts, which would cause overstocking of several commodities such as copper, lumber, and crude oil, to name a few. For example, the price of copper (see Figure 5.2), one of the most price-sensitive raw materials that fluctuates markedly during the business cycle, poses an obvious challenge to producers, namely, when to expand capacity, how much to put into inventory, how much to discount as demand falls, when to close mines as demand slows, and so on.

Figure 5.2 Global price of copper

Source: International Monetary Fund, Global price of Copper [PCOPPUSDM], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCOPPUSDM, December 11, 2020.

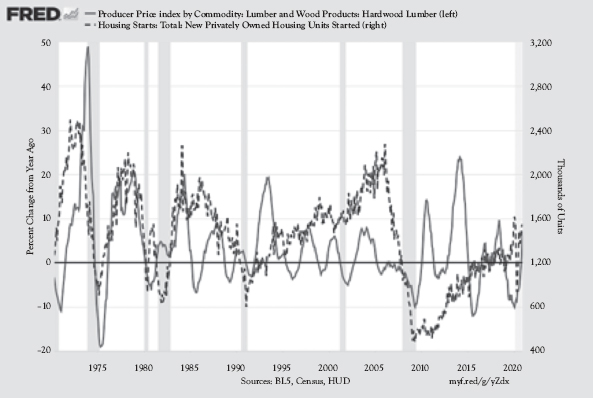

The same concerns apply to lumber, where production is highly correlated with housing starts, a key indicator of the business cycle (see Figure 5.3). Although the correlation is not “perfect,” the volatility in lumber prices reflects how this commodity is affected by factors other than just housing starts and the business cycle (recessions are shaded gray).

U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Housing starts: Total: New privately owned housing units started [HOUST], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/HOUST, December 21, 2020.

Lastly, the price of crude oil (see Figure 5.4) has had a history of widespread volatility since the first oil crisis in 1973–1974 and then again in the late 1970s. The collapse in all prices in the mid-1980s and then the spike a few years later wreaked havoc with the economies of such cities as Houston, which is at the epicenter of the oil trade in the United States. Commercial real estate was overbuilt in Houston and the subsequent collapse in prices (mid-1980s) and then again in the early 1990s created enormous opportunities for investors who had the cash or the ability to borrow from the banks to purchase real estate properties and/or oil properties at depressed prices.15 And since the end of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s, the price of oil has been on amazing roller coaster for the past two decades.

Figure 5.3 Lumber and wood products and housing starts

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Producer price index by commodity: Lumber and wood products: Hardwood lumber [WPU0812], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WPU0812, December 21, 2020.

Figure 5.4 Spot crude oil price: West Texas Intermediate

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Spot crude oil price: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) [WTISPLC], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WTISPLC, December 20, 2020

With the push for electric cars throughout the world, the question remains whether the price of crude oil will be permanently repressed, or if another bout of price inflation in the 2020s will lift crude oil prices and other commodities well above their current levels. And another variable that could impact the price of oil would be any new initiatives to reduce the use of hydrocarbons in the coming decades from the Biden administration. Thus, oil producers will be hard-pressed to forecast an accurate price of oil for the remainder of the decade.

A sustained rise in commodity prices, however, is a real possibility based on the enormous increase in the money supply during 2020. According to several analysts, the “money pump” to counter the effects of the COVID-19 lockdowns will boost prices in general and commodity prices in particular.16 Previous commodity booms were preceded by easy money policies in the United States and around the world.17

The bottom line for managing raw materials and the supply chain is to be flexible and nimble, especially as the business cycle unfolds over time. Several tactics should be pursued for both material producers and raw material users. Raw material suppliers should monitor economic conditions as closely as possible and avoid overstocking their inventory. Insofar as an inverted yield curve is a precursor to a recession—and the cable business channels report on this phenomenon frequently—the lead time before a recession begins should give managers ample time to decide if the “big one” is coming—a downturn that could cause a precipitous drop in commodity prices.

For users of raw materials, having several suppliers during the boom is important to avoid any production bottlenecks. Relying on one or even two suppliers during the boom when commodity prices are typically rising could have a negative impact on the bottom line if prices of a company’s output cannot be raised to cover its cost hikes. One way to avoid prospective price hikes during the boom is to make pre-emptive purchases. The danger here is increasing inventories of several commodities could backfire if a recession occurs soon thereafter when commodity prices may be falling. Thus, purchasing agents must try to gauge strength of the boom and forecast when the downturn may occur to minimize the negative impact of rising and falling commodity prices.

Intermediate Products

In the supply chain, intermediate products are in effect a way station to eventually reaching the consumer. Intermediate products can be characterized as durable and nondurable goods. Durable goods would include wood products, nonmetallic mineral products, primary metals, machinery, computer and electronic goods, motor vehicles and parts, among others. Nondurable goods would include relatively recession-proof products such as food, beverages, and tobacco and more economically sensitive products such as textile and product mills, paper, apparel and leather, petroleum and coal products, chemicals, and plastic and rubber products. These products are thus processed to satisfy consumers’ demands, both durable and non-durable goods, which will be reviewed in the next section.

During the business cycle, we would expect durable manufacturing, one of the most economically sensitive sectors, to fluctuate more than the nondurable manufacturing sector. Over the course of many cycles since the mid-1970s, durable manufacturing rose faster during booms and fell greater in the bust than the less-sensitive nondurable manufacturing sector. The drop in manufacturing during 2020 was not your typical business cycle plunge and recovery. However, Figure 5.5 reveals that manufacturing was beginning to slow down during 2019, before the pandemic lockdown pushed manufacturing over the cliff. In other words, a typical cyclical slowdown was unfolding as in previous cycles with nondurable goods contracting faster this time than durable goods manufacturing.

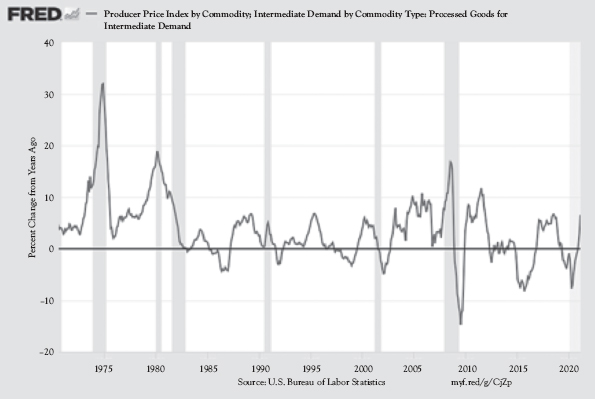

As far as intermediate goods prices are concerned during the business cycle, Figure 5.6 highlights the gyrations since the first oil shock recession of 1973–1975. Intermediate goods prices tend to decelerate prior to the start of a recession and occasionally decline year-over-year. The sharpest decline occurred during the housing bust of 2007–2009 when petroleum products prices plunged, driving the index into negative year over year change (see Figure 5.7).

For intermediate goods producers, the challenges during the business cycle are as follows. During the boom phase, as raw material prices are increasing a company’s margins may be squeezed if it cannot pass its higher input costs on to wholesalers and/or retailers. Depending upon the industry of the intermediate goods supplier, resistance to higher prices in the early stages of the boom may be significant. However, as the boom unfolds, wholesalers and retailers may be more willing to pay higher prices because the injections of new liquidity that kick-started the boom may be sufficient for them to pay the higher prices and pass on higher prices to consumers. For example, the price of inputs to computer manufacturing may be increasing, and if the final demand for computers is also robust, then computer manufacturers should have no problem raising prices.

Figure 5.5 Durable and nondurable manufacturing

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Industrial Production: Durable Manufacturing (NAICS) [IPDMAN], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IPDMAN, December 22, 2020.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Industrial Production: Non-Durable Manufacturing (NAICS) [IPNMAN], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IPNMAN, December 22, 2020.

Figure 5.6 Intermediate goods prices

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Producer price index by commodity: Intermediate demand by commodity type: Processed goods for intermediate demand [WPSID61], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WPSID61, March 25, 2021.

Figure 5.7 Processed energy goods prices

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Producer Price Index by Commodity: Intermediate Demand by Commodity Type: Processed Energy Goods [WPSID69113], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WPSID69113, December 22, 2020.

When the boom reaches a peak, intermediate goods manufacturers may be in a major price squeeze as raw materials may still be rising but the final demand is flattening or beginning to decline. And if intermediate goods manufacturers have overestimated final demand, they may have inventories piling up just as final demand prices are falling.

Retail Supply Chain

Not long ago, the supply chain for retailing was quite simple. Manufacturers would ship their products to wholesalers who in turn would send the merchandise to department stores, grocery stores, and other retail outlets. Consumers, in turn, would make their purchases at the local mom-and-pop shop or nearby department store or in a store located in a mall if they lived in the suburbs. As retailing evolved, consumers could order products through a mail order catalog. And the introduction of a toll-free 800 number for ordering without having to leave one’s home made shopping a relatively seamless experience—which was made famous by such well-known retailers as Sears and L.L.Bean.

The commercialization of the Internet has led to one of the greatest shifts in consumer spending in history. Instead of the traditional supply chain, e-commerce has created a more “layered” distribution of goods from the manufacturer to the customer. Now, manufacturers can send their goods not only via the long-standing supply chain but also to a regional distribution center, which in turn would send the merchandise to a “front distribution center (FDC).” The FDC has the option of sending directly to the retailer or to the customer. In addition, the wholesaler now has three options in the supply chain; the merchandise can be shipped to the regional distribution center, the front distribution center, or the retailer.18

E-commerce has caused a substantial transformation of consumer shopping habits and has created additional challenges for retailers, online platforms, and manufacturers. Consumers want quick, free shipping and free return shipping. At a minimum, consumers want merchandise delivered in two days and to be able to return an item hassle-free, which means receiving a return shipping label with packaging. This obviously poses both challenges and opportunities. E-commerce retailers have had to invest heavily in automation, artificial intelligence (AI), logistics, and other tools to get products out the door as rapidly as possible, and to be able to satisfy customers who were dissatisfied with their purchase.

Consumers, being tech savvy these days, comparison shop to get the best deal possible creating enormous price pressures for retailers. Unless productivity rises for online retailers, profit margins will tend to be squeezed as consumers scan to comparison shop on their smart phones in a brick-and-mortar store and see what the best deals are online. In fact, a strong case can be made that one of the reasons consumer price inflation has been kept at bay for the past 20 years, especially on the goods side, is the fierce competition for the consumers’ dollars. Consumers have more information at their fingertips than they ever had before, and retailers therefore have to be superefficient to maintain sales in the most competitive retail environment in our history. Thus, the long-term secular trend in retail prices should be down for the reasons stated previously. The phrase “The consumer is king” is more appropriate today than at anytime since the first department store was opened in the 19th century.

Price deflation is the hallmark of a free market economy but has been interrupted by bouts of price inflation, which we have witnessed prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 and since then. Inasmuch as consumer price inflation has been in a downward trend for four decades, will this trend continue or will another price inflation cycle unfold in the 2020s? If consumer prices will accelerate in the future, what does this portend for the retail supply chain?

During the boom phase of the business cycle, consumer prices in general tend to rise or even rise moderately and occasionally decline, as was the case during the Roaring Twenties. Each product and service therefore has an “inflation cycle” over the course of the economy’s boom and bust. A price index does not capture the dynamics of individual sectors and companies within those sectors. If consumer demand were robust in some sectors, manufacturers and then retailers would be able to pass along higher costs to consumers. If consumers were price-sensitive, they would tend to balk at higher prices or seek out lower price alternatives. This poses a challenge for both manufacturers and retailers, namely, how much of their costs would they be able to pass on to consumers during the boom phase of the cycle? On the other hand, if prices in general are rising (e.g., the double-digit price inflation of the 1970s), consumers may be making pre-emptive purchases in order to avoid higher prices in the future. This is one of the defenses consumers have to protect themselves from rising prices during the boom. And when the recession begins with unemployment climbing and consumers become more anxious about keeping their jobs, even as price inflation is moderating, they will tend to reduce their purchases of discretionary items such as jewelry, clothing, new automobiles, and any other merchandise that could be postponed for an indefinite period of time during the downturn and possibly into the early months of the ensuing upswing in the economy.

What tactics and strategies could corporate managers and small business owners implement to deal with the challenges of the business cycle? One obvious tactic is to lock in prices of goods for upcoming seasonal merchandise in the expectation of higher wholesale prices. If retailers and wholesalers contract with manufacturers a set price months before production, then they could reap the benefits of higher price inflation in general as the new money that has been created “trickles down” to consumers in the later phase of the boom cycle. The downside to this tactic is that manufactures may want retailers and wholesalers to commit to a certain amount of production to lock in a price. That could be problematic if final demand does not materialize as much as businesses expect for the inventory that has been purchased in anticipation of higher prices and sales. Nevertheless, managers and small business owners could “do nothing” and pay higher prices as the merchandise moves along the supply chain and then observe consumer reactions to the price inflation. Creative marketing then would be needed to move the higher priced merchandise such as “Beat the price hikes. Buy now!” campaign or other inducements to keep real sales from declining. Thus, if retailers have extensive knowledge of their customers’ needs and wants and price sensitivities, they should be able to navigate the challenges during the inflationary boom.

As the recession unfolds, retailers may find that consumers are even more price-sensitive as economic uncertainty pervades society. During the economic downturn, profit margins would be under pressure as sales may be flat or declining and costs may still be rising. Retailers then could be in a position to get price concessions from wholesalers and/or manufacturers in order to move merchandise to the consumer. For retailers, therefore, it would be prudent to have more than one or two wholesalers in their supply chain so they could survive the bust phase of the cycle and be in a position to thrive when the next upswing in the economy begins.

Conclusion

The business cycle, unfortunately, will be with us for the foreseeable future. As long as the Federal Reserve creates new money and manages (manipulates) short-term interest rates, the U.S. economy will experience periodic booms and busts. That’s the bad news. The good news is that inventors, innovators, and entrepreneurs will continue to provide consumers with new and better products. That has been the history of business since the beginning of the republic. Unfortunately, the pandemic of 2020, which may have had the greatest transformative impact on the structure of American businesses and the supply chain, has already caused winners and losers to emerge (as of this writing at the end of 2020) in the so-called new normal.

That pandemic has caused most, if not all, businesses to rethink the supply chain they depended upon before COVID-19 hit America’s shores. Businesses that have depended upon some of their inputs from overseas may be realizing that globalization—the international division of labor and specialization—may be unreliable as geopolitics, tariffs, and health concerns may make them seek domestic supply chain partners to replace foreign sources of raw materials, intermediate goods, and consumer merchandise. Nevertheless, the long-term decline in U.S. manufacturing may have ended with the pandemic, according to economics professor Douglas A. Irwin. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Irwin observes, “there is a natural tendency to turn inward and reduce dependence on others. People begin to value security more than efficiency.”19 In the same Wall Street Journal issue, Scott Davis, chairman and CEO of Melius Research, notes that manufacturing is making a comeback because of the pandemic. He points out that the winners in 2020 include hardware stores and HVAC suppliers as Americans have been improving their homes with the resources they otherwise would have been spending on restaurants, traveling, and other purchases.20 Davis’ optimism is based upon the localization of the supply chain and the innovative factors—data analytics, cloud computing, and AI—which will make American manufacturing more competitive in the global economy. He also reports that investments in these areas have provided widespread benefits such as “higher safety levels, higher employees’ morale, lower turnover among staff, higher quality control, faster new-product cycles, and lower environmental impacts.” In other words, U.S. manufacturing may be entering a new Golden age.

On the retail front, well-known clothing brands have decided to begin selling their upscale products at Target, Walmart, and Tractor Supply Company. The strategy has paid off for such brands as Levi Strauss, Steve Madden, and others who realized that their lower-priced brands would not be cannibalized and the foot traffic at the big-box stores would bring in consumers to purchase their full-price items.21

Entrepreneurs are adapting to the new normal as the fallout from the pandemic of 2020 unfolds. Unfortunately, the restaurant industry has taken a huge hit throughout the country as thousands of restaurants have already closed and thousands more are on the brink of closing their doors as 2021 begins.

To survive and thrive in the new normal of a postpandemic world with another economic downturn inevitable, corporate managers and small business owners will be put to the test to recognize the business cycle turning point and take appropriate actions to increase profitability, gain market share, or form strategic alliances.

The next chapter will focus on how businesses can improve their workforces during the economy’s boom and bust.