CHAPTER 3

Program Strategy Alignment

This chapter provides an in-depth analysis of the program strategy alignment domain. It describes the criticality of program alignment with the organizational strategy and the elements that a program manager and a program sponsor create to ensure program strategy alignment throughout the program life cycle. These elements include program business case, road map, environmental analysis, and phase-gate review.

During the definition phase, to ensure initial program alignment with the organizational strategy, a program manager creates a business case and a road map. The program manager also conducts an environmental analysis, the results of which become an input to the business case and a road map. During the benefits delivery phase, a program manager conducts phase-gate reviews to ensure the program's continued alignment with the organizational strategy.

This chapter covers the following key aspects:

- Organizational strategy and program alignment;

- Business case;

- Road map;

- Environmental analysis; and

- Phase-gate review.

Organizational Strategy and Program Alignment

A key difference between program and project management is the strategic focus of programs. Programs are designed to align with organizational strategy and ensure organizational benefits are realized.1 It's not enough for projects and programs to come in on time and on budget. They must also be in sync with strategy, or “it's just wasted capital.”2

Organizations build strategies to define how the vision will be achieved. Every year, organizations go through an annual strategic planning cycle, where organizational vision and mission are translated into a strategic plan within the boundaries of the organizational values. The strategic plan consists of initiatives that are influenced in part by market dynamics, customer and partner requests, shareholders, government regulations, and competitor plans and actions. Initiatives may be grouped into portfolios to be executed during a defined period. Portfolios also consist of programs and projects that execute the strategic plan, realizing identified benefits, and, subsequently, execute organizational strategy.

The goal of linking portfolio management with organizational strategy is to establish a balanced, operational plan that will help the organization achieve its goals and balance the use of resources to maximize value in executing programs, projects, and operational activities. The strategic planning and portfolio management processes identify and measure benefits for the organization. They provide programs with a definition of the expected outcomes and results. Organizations initiate programs to deliver benefits and accomplish agreed-upon outcomes that often affect the entire organization. During the program initiation phase, organizations conduct feasibility studies to clarify and define program objectives, requirements, and risks to ensure a program's alignment with the vision, mission, organizational strategy, and objectives.3

It has been observed that some organizations do not follow through on the strategic plan execution. Frequently, the strategic plan does not fully cascade down to the program level, creating a gap between strategy formulation and strategy execution. Sometimes, organizations do not establish quantitative and qualitative measures to evaluate execution of the strategic plan and quality of the realized benefits. And, at times, upon program completion, organizations fail to align ongoing operations with implemented changes and incorporate benefits realized through the program execution to the ongoing operations.

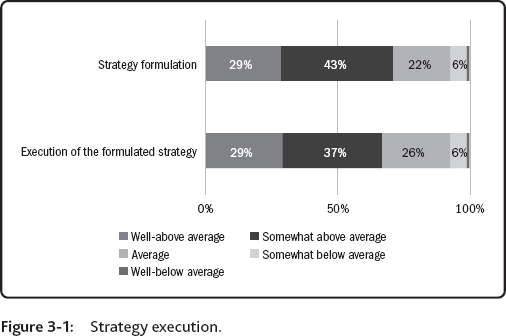

Statistical evidence shows that an alarmingly small percentage of organizations execute formulated strategy well-above and somewhat above average compared to peer companies, as shown in Figure 3-1.

Only 39% of organizations consider prioritization and funding of the appropriate strategic initiatives and projects to be essential, 48% of organizations consider prioritization and funding of the appropriate strategic initiatives and projects to be very important, and the remaining 13% consider prioritization and funding of the appropriate strategic initiatives and projects to be somewhat important. Only 56% of organizations find successful project execution essential for strategic results delivery, and 34% and 10% of organizations find successful project execution to be very important and somewhat important for strategic results delivery.4 Even though this statistic was determined based on the analysis of the project management industry, we will assume that, to a large degree, it also represents the program management industry.

By supporting strategic program implementation, the program management office plays a crucial role in the delivery of the organizational strategy. Organizations that have project management offices with broader business-wide responsibilities, such as an enterprise program management office (EPMO), are closest to the delivery of the strategic value. With the responsibility for aligning projects and programs to corporate strategy, the EPMO establishes and oversees the appropriate governance of enterprise portfolios, programs, and projects; and performs portfolio management functions to ensure strategy alignment and benefits realization.

Effective executive sponsorship is critical to the success of organizational strategy initiatives—an executive sponsor's active engagement is the top driver of project and program success. Data show that, out of all projects with executive sponsors, 76% of projects meet goals or intent. And data show that, out of all projects that do not have executive sponsors, only 46% of projects meet goals or intent. Despite this finding, only three in five projects have engaged executive sponsors. Effective executive sponsors have a thorough knowledge of a project and how it connects to business strategy. And owing to their position and experience, they have the necessary skills and authority to clear roadblocks, the confidence to make quick and effective decisions, and the influence to champion the project with senior management and position it as a top priority. The best executive sponsors can also motivate and engage a project team.5

To fully realize program benefits, it is critical to ensure program alignment with the organization's long-term goals and strategy. Alignment refers to the degree to which a program mirrors and supports the priorities of the organization's business strategy. Additionally, it is the degree to which the business strategy is used to guide objectives and work outcomes of the execution team.6

Program strategy alignment is achieved through the program vision and program selection process. The program vision is the keystone element that establishes the end state that defines success for the program and provides guidelines for what to do and how to do it. It is rare that the successful execution of a single program results in the attainment of all strategic goals. Rather, it takes the successful execution of some programs within the portfolio. Each program then carries a set of program objectives that are designed to achieve specific strategic goals. The program objectives provide the translation from strategic business goals to actionable execution objectives specific to a program.7

We will illustrate how organizational strategy translates into program objectives by using the call center's process improvement program example. An organization has a strategic goal of providing the highest call response quality and fastest call response time. This strategic goal translates into the call center's process improvement program objectives:

- Improve call response quality; and

- Decrease call response time.

We discussed how program strategy alignment is achieved through a program vision. And now, we will discuss how program strategy alignment is achieved through the program selection process. The program selection process depends on where the organization operates along the program management continuum, in the project-oriented or program-oriented space. Project-oriented organizations may have a limited process of selecting programs that are aligned with organizational strategy. Frequently, project-oriented organizations limit their program selection to the programs that permit execution of tactical initiatives.

Program-oriented organizations are likely to have a formalized program selection process that starts with formulating an organizational strategy. During strategy formulation, the organization defines strategy and determines how and during what period it will be executed. An outcome of this work is the strategic plan, a document that outlines organizational strategy and its execution. Once the organizational strategy is formulated, an executive steering committee selects programs, the execution of which will allow the organization to execute strategy. Once programs are selected, the organization commits resources and starts the program definition phase. The program definition phase confirms if identified programs are the most appropriate to execute organizational strategy and realize program benefits.

The definition phase begins with confirming the need for a program and identifying benefits that a program will realize, both of which are summarized in the business case. A program road map translates the business case into a valuable program execution tool that chronologically represents the program's intended direction. Environmental analysis is conducted to provide an input to the business case and a road map to ensure that a program will deliver expected benefits within the environment where it operates. All of these elements become inputs to a program management plan that establishes an outline for executing organizational strategy and realizing program benefits through the program life cycle. The program management plan will be discussed in detail in Chapter 8: Program Management Infrastructure.

Business Case

The business case is developed during the definition phase. The business case is developed to assess the program balance between costs and benefits. The business case is a document written for executive decision makers, assessing the present and future business value and risks related to a current investment opportunity.8 A good business case brings confidence and accountability into making investment decisions. The business case is a compilation of information collected during the enterprise analysis and business case processes. The business case is created to help the executive sponsor and stakeholders ensure that a program has value and relative priority compared to alternative programs, based on the objectives and expected benefits laid out in the business case.

In program-oriented organizations, a program manager leads business case preparation. The program manager also collaborates with key sponsors to develop the program business case. The business case can be brief or comprehensive, depending on the organizational structure, and where it operates—in the project-oriented or program-oriented space. The comprehensive business case likely includes program background, benefits, costs, a gap analysis, and known risks.

The purpose of the program business case is to demonstrate that a program supports the strategic goals of the organization and is used to determine if the organization should invest the financial, human, and capital resources to execute the program fully. Portions of the business case are vital in establishing the program vision by describing the business opportunity available and how the program will achieve the opportunity and business strategy. The business case connects the organizational strategy and objectives to the program objectives and helps identify the level of investment and support required to achieve the program benefits.

The program business case spells out the business benefits of the program and the rationale as to why users, customers, or the organizations desire the program outcome, and why it is better than other alternatives. Most importantly, the business case demonstrates that program benefits will exceed program costs over time. The business case is core to the establishment and execution of the program vision because it is the means of securing the funding and resources necessary to execute the program and for continually evaluating the progress of the program toward achieving the strategic business goals intended.9

The business case may be documented in many ways. However, there is a structural framework of the kinds of information that should be included in the business case. At the same time, as every program is different, a comprehensive and convincing business case needs to address a program in context. That may require adding new sections to the structural framework or regrouping material as necessary to address the specifics of a program and the organizational environment it operates in.

The comprehensive business case likely has a framework that includes an executive summary, program strategy alignment, program scope, return on investment (ROI), assumptions, benefits, risk analysis, estimated time line, estimated costs, program team structure, program team roster, supporting subject matter experts, recommendations, and appendices.

An executive summary introduces and describes a program, its benefits, the ROI, and estimated timing to execute it. In simple terms, the executive summary describes what a program is about, how much it will cost, and what benefits it will deliver and when.

Using the strategic plan as an input, the program strategy alignment section describes how the program will execute organizational strategy.

The program scope section defines general program scope. Detailed program scope is defined in the program management plan during the program benefits delivery phase when all program information is known.

The return on investment (ROI) section calculates profit gained after program execution is weighed against program costs. The calculation may show short-term and long-term ROI as well as ROI each year during a defined period.

The assumptions section includes a list of assumptions that must hold true for a program execution to be successful. Each assumption includes an impact that describes what would happen to a program execution if the assumption does not hold true (e.g., it may result in execution delay or in cost increase).

The benefits section, in quantifiable terms, defines program benefits that will be realized after program execution.

The risk analysis section lists all known risks that can impact program execution. Each risk includes a description, the probability of occurrence, mitigation strategy, persons responsible for risk mitigation, target resolution date, and risk impact on the program, categorized as high, medium, or low.

The estimated time line section describes all phases of the program life cycle. Each phase has scheduled start and finish dates. And, each phase includes key deliverables and milestones, along with corresponding dates.

The estimated costs section itemizes program costs for the entire program life cycle, broken down by program phases. Costs may also be broken into various categories (e.g., operational and capital).

The program team structure section describes team member roles, and it documents relationships among program team members using an organizational chart.

The program team roster lists the candidates for each role on the program team. It includes names, titles, skills, and percent allocation to the program.

The supporting subject matter experts section lists individuals who will not be members of a program team, but will provide subject matter expertise when needed. The list includes roles, names, positions, and descriptions of the subject matter expertise.

The recommendation section includes a recommendation for program approval or denial, and outlines reasons for a recommendation. The reasoning is substantiated by the findings discussed in the preceding sections of the business case.

Appendices may include supporting data, research reports, associated documents, and other supporting materials.

Once the program business case is completed, the program manager reviews the business case with the executive sponsor and stakeholders and gains their approvals. Once approved, the business case establishes the authority, intent, and philosophy of the business need. The business case also serves as a formal declaration of the value that the program is expected to deliver, and a justification for the resources that will be expended to deliver it. The business case is a key input for organizational leadership to charter and authorize programs.10

One of the top issues we hear from our training clients is that projects often get justified or initiated by the solution. The issue results from a project either not having a business case or having a business case with insufficient content. The resulting solution then often doesn't completely solve the underlying problem: rework then results; and the ongoing pain the project was intended to address will continue.

Inadequate or nonexistent business cases usually result in unclear project scope, often leading to scope creep, which results in rework, cost overruns, and delays. Also, inappropriate approaches on projects often lead to rigid solutions, such as selecting a commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) package when a custom solution is warranted. Missing or ineffective business cases also tend to cause numerous changes and time and cost overruns, because the product requirements are often not clear up front.11

As the business case is sometimes mistaken with the statement of work (SOW), it is important to outline how the two documents differ from one another. A statement of work and a business case serve different purposes and, therefore, contain different information. A statement of work (SOW) is a document routinely employed in the field of project management. It defines project-specific activities, deliverables, and time lines for a vendor providing services to the client.12 A statement of work outlines products and services that will be provided by projects. It is a document that is created for external use. The business case confirms the business need and justifies funding for the project by providing cost-benefit analysis. It is created for internal use.

Road Map

The program road map should be both a chronological representation in a graphical form of a program's intended direction as well as a set of documented success criteria for each of the chronological events. It depicts key dependencies between major milestones, communicates the linkage between the business strategy and the planned prioritized work, reveals and explains gaps, and provides a high-level view of key milestones and decision points. The road map also summarizes key end-point objectives, challenges, and risks, and provides a high-level snapshot of the supporting infrastructure and component plans.

The program road map can be a valuable tool for managing the execution of the program and for assessing the program's progress toward achieving its expected benefits. To enable effective program governance, the program road map can be used to show how components are organized into major stages or blocks; however, it does not include the internal details of the specific components.13

The business case provides input to the road map. A program manager may use the road map template developed within the organization or may build a road map using software packages like PowerPoint, Excel, or Microsoft Project. Excel and Microsoft Project have free road map standardized templates.

To illustrate how to build a road map, we will use the call center's process improvement program example. As was described earlier, the program includes subprogram one that includes project one—improve call response quality—and project two—decrease call response time. The program also includes project three—implement projects one and two in all call centers. During the program definition phase, the following program and component information is available:

- The program is scheduled to start on 3 October 2016.

- Phase 1 of the program includes executing project one. Project one is scheduled to start on 3 October 2016. It has a duration of three months, and project one will deliver benefits on 30 December 2016.

- Phase 2 of the program includes executing project two. Project two is scheduled to start on 2 January 2017. It has a duration of three months, and project two will deliver benefits on 31 March 2017.

- Phase 3 of the program includes executing project three. It is scheduled to start on 3 April 2017. It has a duration of six months, and project three will implement projects one and two in all call centers on 29 September 2017.

- The program is scheduled to end on 29 September 2017.

Using the information outlined above, a program manager built the call center's process improvement program road map in Excel, as shown in Figure 3-2.

After program approval, the road map becomes one of the key inputs to the program management plan; the first draft of which is built during the program definition phase, as will be described in Chapter 8: Program Management Infrastructure.

Environmental Analysis

Internal and external factors influence any program, impacting program execution success. Internal factors are factors that exist within the organization but outside the program. Organizational structure is an example of an internal factor that impacts a program. Whether an organization is project-oriented or program-oriented defines many aspects of program execution, including program structure and the program manager role. Examples of internal factors include corporate culture, funding, and resource availability. External factors are factors that exist outside the organization. Examples of external factors include regulatory requirements, political instability, and natural disasters.

Environmental analysis is a process of identifying internal and external factors, analyzing their impact on a program, and developing a plan to mitigate risks that internal and external factors present to the program. There are many types of environmental analyses, including comparative advantage analysis; feasibility studies; assumptions analysis; historical information; and strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis.

Comparative advantage analysis is a comparison of a program with real or hypothetical programs. The analysis uses the business case as a main source of information. The analysis takes into consideration that a program may have competing efforts that either reside within an organization or are external to it. It also includes a what-if analysis of how program benefits may be realized by other means.

Feasibility studies analyze the feasibility of a program within an organization, including funding and resource availability, complexity, and constraints. A feasibility study uses the business case as a main source of information.

Assumptions analysis is a process of identifying and documenting program assumptions. It is an iterative process performed throughout the program life cycle. Initially, program assumptions are identified during the definition phase, and they are validated during the benefits delivery phase to ensure that the assumptions have not been annulled by new information and program activities.

Historical information analysis identifies success factors and reasons for the failure of the programs that the organization completed in the past. Historical information analysis uses all artifacts from the previously completed programs, including business cases, road maps, environmental analyses, risks logs, and program management plans. Historical information analysis becomes a source of lessons learned from the previously completed programs and best practices for the future programs.

SWOT is an analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the program. This analysis helps identify program risks and provides information for the program charter and program management plan.

Phase-Gate Review

It is important to choose the right program that will allow executing organizational strategy. However, it is equally important to continue to ensure program alignment with the organizational strategy throughout the program life cycle. Elements that ensure program alignment during the definition phase are a business case, road map, and environmental analysis, as was discussed in the preceding sections. Elements that ensure program alignment during the benefits delivery phase are phase-gate and readiness reviews.

Phase gate is a review at the end of a phase in which a decision is made to either continue to the next phase, continue with modification, or end a project or program.14 Phase-gate review is conducted at the end of each phase of the program. The review uses multiple criteria, including continued assurance of the program alignment with organization strategy. Phase-gate review criteria include:

- Business rationale that confirms the program continued business need and the organization's strategy alignment;

- Quality of execution that confirms quality of benefits; and

- An action plan that confirms timing and resources needed to continue program execution.

1 PMI. (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

2 PMI. (2014). The project management office: Aligning strategy & implementation. Newtown Square, PA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.pmi.org/-/media/pmi/documents/public/pdf/white-papers/pmo-strategy-implement.pdf

3 PMI. (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

4 PMI. (2016). Pulse of the profession®: The high cost of low performance—How will you improve business results? Newtown Square, PA: Author.

5 PMI (2016). Pulse of the profession®: The high cost of low performance—How will you improve business results? Newtown Square, PA: Author.

6 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

7 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

8 Larson, R., & Larson, E. (2011). Creating bulletproof business cases. Minneapolis, MN: Watermark Learning.

9 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

10 PMI. (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

11 Larson, R., & Larson, E. (2011). Creating bulletproof business cases. Minneapolis, MN: Watermark Learning.

12 Statement of work. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Statement_of_work

13 PMI. (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

14 PMI. (2015). PMI lexicon of project management terms, Version 3.0. Newtown Square, PA: Author.