CHAPTER 2

What Makes a Successful Program Manager?

The program manager is a key driver of a successful program execution. A program manager executes a program by setting up program structure, leading project managers, and delivering program benefits. That is why it is very important to define a program manager role and understand what helps a program manager to succeed in it.

This chapter describes how the organizational structure defines a program manager role. The chapter introduces the program management continuum, a concept that defines four phases within the project-oriented and program-oriented organizational structures. It defines a program manager role in each phase of the program management continuum. The chapter illustrates how program infrastructure enables a program manager to lead. It introduces a proficiency framework examining proficiencies that make a successful program manager. The chapter concludes with a table that compares program, project, and portfolio managers’ roles.

The chapter includes the following sections:

- Organizational structure empowers program manager to lead;

- Program manager role;

- Program infrastructure enables program manager to lead;

- Proficiency framework makes a successful program manager; and

- Comparison of the program, project, and portfolio managers’ roles.

Organizational Structure Empowers a Program Manager to Lead

Currently, there is a signification variation in how the program management function is utilized across organizations. Some organizations utilize the program management function to its fullest, making it a business extension. While other organizations utilize program management in a limited way, as only administrative or facilitative.

Organizational structure defines how program management is practiced in the organization and defines the role that a program manager plays. We define four types of organizational structures for program management. We also discuss how each of the four types of organizational structures utilizes the program management function and defines a program manager role.

Variation in the program management function drives variation in the program manager role. To understand how different a program manager role can be, it is important to define program management function types and examine how they influence the program manager role.

Some organizations establish their program management function as administration-focused, some as facilitation-focused, and others as integration-focused, and still others as business-focused. This approach to program management within the organizational structure is called the program management continuum, and it is graphically displayed in Figure 2-1.1

Organizations that fully utilize program management, and often view it as a part of the business management function that provides a link to the organizational strategy, are program-oriented organizations. Program-oriented organizations can be either integration-focused or business-focused. In these organizations, a program manager is empowered to deliver business results.

Organizations that do not utilize program management to its full capacity and view program management function only as an extension of the project execution that primarily realizes administrative needs, are project-oriented organizations. Project-oriented organizations can be either administration-focused or facilitation-focused. In these organizations, a program manager role is limited to performing administrative work and executing projects.

Details of the stages of program management continuum reveal different views on—and use of—the program management function as well as show variations in the roles and responsibilities of program managers in each stage.2

Project-oriented organizations include:

- Administration-focused organizations demonstrate a strong focus on independent projects and provide line management control of the projects. These organizations have a limited program management function, and it is utilized primarily for performing administrative tasks, gathering data, and monitoring activities.

- Facilitation-focused organizations are project-oriented. However, projects are grouped into programs, usually organically rather than strategically. Program management serves as a coordination function that facilitates cross-project communication and low-level collaboration.

Program-oriented organizations include:

- Integration-focused organizations view projects as a part of a program that is driven by organizational strategy. At this point in the continuum, control of the projects shifts from a functional or a line manager to a program manager. The primary focus of program management is integration and synchronization of workflow outcomes and deliverables of multiple projects to create an integrated solution that aligns with organizational strategy.

- Business-focused organizations are fully devoted and disciplined in their use of program management practice. Programs are tightly linked to organizational strategy and serve as the strategy implementation mechanism that realizes business goals. In the business-focused culture, organizational hierarchical command and control are replaced by the empowerment and accountability of a program manager.

At the center of the program management continuum, between project-oriented and program-oriented organizations, lies a point of transition. This important point represents a decision point where senior leaders make a determined choice to shift their organization from project-oriented to program-oriented.

Organizational structure may limit the program manager role to that of an administrator or a facilitator who executes tasks in the work plan and performs other administrative functions. However, to provide the greatest value to the organization, a program manager must have strong business focus and be able to lead a program relying on in-depth subject matter expertise. Essentially, the program manager needs to operate as the CEO of a program. Integration-focused or business-focused organizational structure supports this role and empowers a program manager to operate at this level.

Senior leadership defines the organizational structure. Changing business needs drive the organizational transition from a project-oriented to a program-oriented structure. Examples of changes include business growth, strategic shifts, changes in the governance structure, and changes in the regulatory and legislative requirements. At the time of the change, organizations assess the current state, and identify gaps between current and future states.

Every organization, whether it is trying to introduce a new or mature existing program management function, has its unique gaps. A gap represents a need for an organizational transformation from current to expected program management function. The organization's senior leadership makes a decision to redefine the organizational structure and implement a new structure to better facilitate business needs. In doing so, the organization closes a gap between program management function current and future states.

A key discovery from the program management continuum is the demonstration of what an organization can achieve when it begins to operate as a program-oriented organization. Program strategy alignment strengthens, and the gain in benefits derived from the use of program management increases the further to the right of the program management continuum an organization chooses to operate.3

The program management function strengthens, and a program manager role shifts toward higher accountability for achieving business results. A program manager becomes responsible for delivering an integrated solution through program leadership, collaboration with business functions, and coordination of multiple projects within a program, as shown in Figure 2-2. A program manager accomplishes this through effective benefits management, as will be described in Chapter 7: Program Life Cycle Management.

A program manager needs to be fully aware of the organizational structure as it defines a program manager role. A clear understanding of the organizational structure helps a program manager understand expectations for the role and identify opportunities to expand it.

The most effective way of establishing the program management function and defining a program manager role is through an organizational structure. However, significant variations in establishing the program management function and in defining a program management role confirm that, at present, it is not a commonly established practice.

In some organizations, program managers—and not senior leaders—establish program management functions and define the program manager role. Frequently, a program manager role is dependent upon the ability of the person serving in it. As a result, program manager success cannot be replicated, and the role has to be redefined if a program manager leaves. All of the above contributes to a significant existing variation in the program manager role that exists not only between organizations, but sometimes even between different departments within the same organization.

In project-oriented organizations, a program manager can help influence a shift to program-oriented organizations, and, in the organizations where the program management function is not clearly defined, a program manager can help structure it. One of the venues through which a program manager can help define the program management function and structure a program manager role is the program management community of practice (PgMCoP), described in Chapter 11: Program Management Community of Practice.

Program Manager Role

The program management function defines the program manager role. The program management continuum identifies four types of program management functions, each of which defines a program manager role differently. Let us examine these roles closely by comparing them in Table 2-1.

To provide the greatest value to the organization, the program management function must be established as having a strong business focus.4 To achieve this organizational structure of a program-oriented enterprise, a program manager role should have the following responsibilities:

- Develop program plan and budget;

- Be accountable for program execution, including program schedule, budget, and quality;

- Review and approve project plans for conformance with program strategy, program plan, and schedule;

- Act as the communications conduit with executive sponsors and the program steering committee, and conduct periodic briefings and status updates; and

- Escalate decisions and risks to executive sponsors.

A successful program manager is a business leader who understands the role, business environment, stakeholders, regulatory requirements, and more. A program manager is not an administrator or a facilitator who simply executes the work plan.

When organizations shift from project-oriented to program-oriented, there is a subsequent shift in the program manager role from administration-focused to business-focused, potentially leading to gaps in knowledge, skills, and experience. To close these gaps and facilitate the transition, organizations have to provide training to program managers. Program managers should assist with identifying gaps between current and future requirements, and identify training needs to close the gaps. One of the venues through which program managers can assist in this process is the program management community of practice (PgMCoP), which will be described in Chapter 11: Program Management Community of Practice.

Program Infrastructure Enables a Program Manager to Lead

The program manager's ability to lead a program is dependent on infrastructure (e.g., a system that supports the program management function, a status reporting tool that aids in monitoring program health, and a financial tool that assists in monitoring program financial health). Infrastructure enables a program manager to execute program operational management tasks quicker, focusing the majority of time on leading a program, delivering its strategic objectives, becoming a trusted advisor, and acting as a subject matter expert (SME).

Program infrastructure should include a plan that allows aggregating project information into a program. The plan can either be Microsoft Project, a spreadsheet, or a database. The system should have the ability to aggregate from multiple projects into program tasks and milestones.5

A program manager should utilize a wide set of tools, including status reports, time lines, resource utilization reports, risk reports, and financial health reports. Program management system support and financial and status reporting tools will be described in detail in Chapter 8: Program Management Infrastructure.

A business-focused program manager should spend about 60% of the time leading a program, and the remaining 40% of the time executing program operational management tasks. This breakdown is possible if a program manager can operate as a business program manager and has effective program infrastructure.

If, due to infrastructure limitations, a program manager spends more than 40% of the time executing program operational management tasks, a program manager cannot lead a program effectively. That is why, at the start of a program, a program manager should assess system capabilities and tools, and determine if they enable effective program management. If a program manager does not have sufficient infrastructure available, a program manager should work with the organizational leadership and professional peers to enhance infrastructure. One of the venues through which a program manager can advocate for system implementation or an upgrade, and get support in developing new and updating existing tools, is the program management community of practice (PgMCoP), which will be described in Chapter 11: Program Management Community of Practice.

Proficiency Framework Makes a Successful Program Manager

In the preceding sections, we have concluded that a program-oriented organization empowers a program manager to lead. We also determined that program infrastructure enables a program manager to lead. In this section, we will review a program proficiency framework that makes a successful program manager.

For many project managers, the next move in their careers is the step up to program manager. Many practitioners lack a true understanding of the role and the skills required to make the transition. Program managers are not simply senior project managers.6

To help illustrate the differences between program manager and project manager roles, we will compare role definitions. Program managers coordinate groups of related projects rather than manage individual projects themselves.7 Project managers are change agents: They make project goals their own and use their skills and expertise to inspire a sense of shared purpose within the project team.8 Role definition comparison illustrates that a program manager role is larger in scope, broader in the framework, and more complex in content than a project manager role is.

Programs differ from projects in an important way; programs need to be managed in a way that enables them to readily adapt to the uncertainty of their outcomes and to the unpredictability of the environment in which they operate. This need influences the proficiencies required of a program manager. To manage a program effectively, program managers need to blend control-oriented leadership and management skills that support execution of the program and its components.9 To succeed in this complex environment, a program manager needs to have various program management proficiencies.

As an organization moves from project-oriented to program-oriented, a program manager spends more time leading a program and less time executing it. Leading a program includes leading a program team, engaging leadership, integrating program work, connecting cross-functional interdependencies, and proactively identifying risks. Executing a program includes completing program operational tasks, updating status reporting, tracking and resolving risks, updating the program management plan, and setting program meeting cadence.

An administration-focused program manager operating in a project-oriented organization spends the entire time executing program operational tasks, with the key one being monitoring the program plan. A facilitation-focused program manager operating in project-oriented organizations spends about 20% of the time leading a program by facilitating low-level collaboration, and 80% of the time executing it.

Once an organization crosses the center of the continuum, a program manager becomes responsible for ensuring that cross-project interdependencies are managed and synchronized. Because of this responsibility, a program manager has to lead the team in their integration effort. In a program-oriented organization, leading a program becomes a more complex effort, as program teams are larger than project teams and, at times, are spread out geographically. Program structure becomes more complex, leading to a multifaceted business governance structure. All these changes require a program manager to spend more time leading a program. That is why program manager proficiencies expand when moving to the right of the program management continuum, enabling a program manager to operate as a business-focused program manager.

An integration-focused program manager operating in program-oriented organizations spends 60% of the time leading a program, including providing cross-project communication and ensuring the cross-project interdependencies are managed and synchronized, and 40% of the time executing a program.

A business-focused program manager operating in program-focused organizations spends 80% of the time leading a program and 20% of the time executing it.10 An experienced business program manager operating in a program-focused organization confirmed that he spends 80% of the time leading a program and 20% of the time executing it. The split between program leadership and program execution is achieved by employing an excellent team of project managers, who work the details of a given project within a program. However, there are times when a program manager needs to drop down into the operational details of a given component to troubleshoot, provide guidance, or work through some technical details.11

The program management continuum graphically shows the percentage of time that program managers spend leading a program and the percentage of time that they spend executing program management operational tasks in each stage, as shown in Figure 2-3.

We developed a program proficiency framework that defines proficiencies that allow a program manager to succeed in leading and executing a program. The proficiency framework groups program proficiencies into three major categories (see Figure 2-4):

- Program leadership;

- Program operational management; and

- Interpersonal skills.

Program Leadership Proficiency

Program leadership proficiency includes:

- Gain in-depth program content knowledge;

- Be aware of the organizational structure;

- Know organizational strategy; and

- Manage stakeholders.

Gain In-Depth Program Content Knowledge

Program content knowledge is essential for successful program execution, as it serves as a keystone for program leadership and program operational management. A program manager needs to develop content knowledge to lead a program successfully, fully realize program benefits, manage cross-functional interdependencies, and be able to identify program and component risks proactively.

Program content knowledge includes an in-depth understanding of a product or a service that a program is developing, who are the customers for it, how the customers will use a product or a service, what the market characteristics are, who the competitors in the market are, and what the market trends and best practices are. Using program content knowledge, a program manager can maximize program benefits realization.

Using the call center's process improvement program example, we will illustrate the importance of program content knowledge in successful program execution. A successful program manager needs to have a fundamental knowledge of services that call centers provide and an understanding of customers who use these services. A program manager also needs to know the market in which call centers operate, competitors in the market, market trends, and the call center's best practices. Bringing this knowledge together, a program manager can improve the call center's processes, ensuring a high level of customer satisfaction and the call center's competitive market position, as well as defining new industry best practices.

The need to have program content knowledge increases as organizations become program-oriented. In-depth program content knowledge is one of the key proficiencies that a program manager needs to master to become successful as a business program manager or a program CEO. To add to program content knowledge, a program manager may engage subject matter experts (SMEs) and business owners.

Understand Organizational Structure

A program manager needs to understand organizational structure, as it defines the program management function that, in turn, defines a program manager role. As was discussed earlier, the business-focused program management function empowers a program manager to lead, while the administration-focused program management function limits the program manager role to administrative functions. A project manager is not required to be aware of the organizational structure.

Know Organizational Strategy

The program manager is required to think strategically to align the program and its constituent projects to the strategic business goals of the organization. This includes understanding how a firm or organization performs strategic planning, and being able to separate aspects of strategic thinking from tactical and operational elements as the need arises. A part of strategic thinking involves a basic understanding of the industry in which a business operates and of how the firm's strategy fits with the direction of the industry long term.12

A program manager needs to know the organizational strategy. A program manager employs strategic vision and planning to align program goals and benefits with long-term organizational goals. Once the program goals and benefits are defined, a program manager develops a program management plan to execute program components. The program manager is responsible for ensuring alignment of the individual plans with the program goals and benefits.13

A program manager needs to observe shifts in organizational strategy to be able to realign a program and components with the changed strategy. A project manager is not required to be knowledgeable about the organizational strategy, as a program manager realigns program components with the changed strategy.

Manage Stakeholders

Stakeholder management skills are critical for program manager success. The program manager first must know how to determine the organizational landscape in which the program is to operate. He or she will likely have many stakeholders, both internal and external to the organization, who need to be influenced.14

It is important to initiate, engage, and maintain stakeholder relationships to manage the program and achieve desired benefits effectively. Active stakeholder engagement helps build and maintain ongoing support of the program. The program manager should identify stakeholders, understand their needs and expectations, develop a stakeholder management plan to support stakeholders, and help align their expectations. The program manager should recognize the dynamic human aspects of each program stakeholder's expectations and manage accordingly.15

Program Operational Management Proficiency

Program operational management proficiency includes:

- Knowing the program governance framework;

- Ensuring the quality of benefits delivery;

- Managing program risks; and

- Executing financial management.

Knowing Program Governance Framework

Program manager proficiencies should include knowledge of establishing and executing the program governance framework. Within a program, a program manager should identify work that is required, build the program management plan, and allocate and optimize resources across all components.

A program manager should define the pacing of components and obtain incremental benefits before the program is complete. While focusing on benefits delivery, a program manager needs to adjust the pacing of components to ensure benefits quality. A project manager defines the pacing of a component on a smaller scale.

Ensuring Quality of Benefits Delivery

The program manager, as the quality champion of his or her program's customers, needs to ensure the program results meet or exceed the quality expectations of the customer. The program manager should possess a bias of action, be able to think globally, and assure that quality, reliability, manufacturability, serviceability, and regulatory compliance objectives are achieved.16

A program manager should compare delivered benefits to the program charter to ensure that the intended and delivered benefits match. Utilizing program content knowledge, a program manager needs to question the content (e.g., will the solution deliver the intended benefits?). It is important to have quality metrics to ensure that the program delivered benefits as defined in the business case. Quality metrics tools can aid in measuring the quality of the benefits, as will be described in Chapter 8: Program Management Infrastructure.

Managing Program Risks

A program manager needs to be able to identify program and component risks proactively. In-depth knowledge of the program content is a key to the program manager's ability to identify and manage risks. The program manager also needs to be able to shift focus between components to give attention to critical risks. A program manager can utilize a program risk-tracking tool to aid with tracking and resolution of program issues. We will discuss the tool in detail in Chapter 8: Program Management Infrastructure.

Executing Financial Management

To be successful from a business perspective, the program manager must possess sufficient business skills to understand the organization's business model and financial goals. This requires that a program manager can develop a comprehensive program business case that supports the company's objectives and strategies, the ability to manage the program within the business aspects of the company, and the ability to understand and analyze related financial measures about the program.17

Programs have significantly larger budgets than projects have. The program budget also often includes expenses and capital expenditures, while the project budget often includes only expenses. So, to be able to execute a program on budget, a program manager needs to have advanced knowledge of financial management and budgeting. Additionally, to be able to identify, investigate, and resolve any variances between the program budget and actuals, a program manager needs to be able to perform a variance analysis. Variance analysis will be described in Chapter 8: Program Management Infrastructure. A project manager also needs to have a knowledge of financial management and budgeting. However, a project manager applies this knowledge on a smaller scale of an individual project.

Interpersonal Skills

Programs frequently operate in a matrix organization. A matrix organization is defined as one in which there is dual or multiple managerial accountability and responsibility. In a matrix, there are usually two chains of command, one along functional lines and the other along the project, product, or client lines.18 In a matrix organization, program team members do not report directly to a program manager, and team members frequently work on more than one project or a program at a time. The complex program environment calls for a program manager to have strong interpersonal skills. Using the call center's process improvement program example, we will illustrate that a complex program environment requires a program manager to have strong interpersonal skills.

The call center's process improvement program team includes project managers for process improvement projects one and two, and the call center's directors. Project managers work in the project management organization, where they manage one or more projects. Project managers are also responsible for the execution of process improvement projects one and two. Call center directors work in the call centers, where they are responsible for their daily operations. Call center directors are responsible for the process improvement program implementation in their call centers.

To successfully execute the call center's process improvement program, a program manager needs to bring the team together under the common goal of realizing the call center's process improvement program benefits. A program manager can do that by developing a variety of interpersonal skills that help them succeed in the complex program environment, including:

- Developing strong leadership skills;

- Developing strong communication skills;

- Thinking broadly, horizontally, and top-down; and

- Developing soft skills.

Developing Strong Leadership Skills

A program manager needs to have the capability to build, coalesce, and champion the team to deliver a solution that will satisfy the company's goals and the customer's needs.19

A program manager should develop strong leadership skills to lead programs throughout the program life cycle. A program manager leads the program management team in establishing program direction, identifying interdependencies, communicating program requirements, tracking progress, making decisions, identifying and mitigating risks, and resolving conflicts and issues. A program manager works with project managers and functional managers to gain support, resolve conflicts, and direct individual program team members by providing specific work instructions.20

Today's business models have created additional team-building challenges for program managers. It is common for program team members to be distributed across multiple countries. Skills for managing virtual teams have become an emerging critical skill for program managers. There are many aspects to successfully leading a geographically distributed or virtual team.

Leading a virtual program team raises the following question: Is it possible to build true leadership in virtual teams when members are geographically, culturally, organizationally, and time-zone dispersed? Industry expert Patrick Little, a senior IT program manager for a leading research hospital, states that leading a virtual team is possible, but it takes additional effort from all members of the team. Leadership responsibilities include motivating, seeking information and opinions, mediating, facilitating communication, removing barriers, lubricating interfaces, and making each conflict functional so it can be used to improve the quality of our decisions.21

Developing Strong Communication Skills

A program manager needs to have strong communication skills to communicate effectively with various program stakeholders, including sponsors, customers, vendors, and executives. More specifically, a program manager needs to be able to pivot and communicate upward, across, and downward, including:

- Upward externally to the government, industry, and investors;

- Upward internally to the program sponsor and organization executives;

- Across externally to the vendors and customers;

- Across internally to the multiple departments within the organization; and

- Downward to subprogram and project managers.

Effective communication requires the ability to speak multiple disciplinary languages—business language when communicating with senior management, user language when communicating with the customers, technology language when communicating with technologists, and so on. Effective communication skills also mean that the program manager should be able to actively listen and provide clarity in difficult situations, many times serving as the translator in multidisciplinary discussions. The program manager must be able to use and extend stakeholders’ knowledge to develop the ability to choose the right model of communication to address customers, senior management, team members, suppliers, and others. This involves knowing when to see people face-to-face, when to send messages, and when to avoid them altogether.22 And finally, they must effectively communicate, with skills that include being able to write powerful messages to various program stakeholders.

To ensure timely communication with stakeholders, a program manager needs to determine communication frequency. The program management communication plan should address stakeholder needs and expectations, as well as provide key messages promptly and in a format designed specifically for the target audience, as will be described in Chapter 8: Program Management Infrastructure.

Don't wait for stakeholders to read their report and react. As you get to know their habits, you will learn that some need a phone call or targeted email to draw their attention.23 A program manager needs to learn stakeholder habits and work styles and be able to customize program communication plan execution to stakeholder needs.

Think Broadly, Manage Horizontally, and Execute Top-Down

A successful program manager needs to operate on different levels, including thinking broadly, managing horizontally, and executing top-down:

- Think broadly to integrate program components, however be in the low-enough level of details to proactively identify program and component risks;

- Manage horizontally and ensure that the cross-component work effort remains feasible from a business standpoint and realizes benefits; and

- Execute top-down by implementing structure on a program level and executing it on a component level.

In program management, delivering the whole solution is a primary means of achieving customer satisfaction. The program manager needs to be able to demonstrate a commitment to the customer and demonstrate knowledge of customer application and needs. Those skilled in systems thinking can view projects and activities from a broad perspective that includes seeing overall characteristics and patterns rather than just individual elements. By focusing on the entirety of the program, or in essence, the system aspects of the program (inputs, outputs, and interrelationships), the program manager improves the probability of delivering the whole solution and meeting the expectations of the customer. This involves the ability to see the big picture, crossing boundaries, and being able to combine disparate elements into a holistic entity. Usually this ability resides in people with diverse backgrounds, multidisciplined minds, and a broad spectrum of experiences.24

A program manager needs to think broadly to be able to integrate multiple program components together as a package. Additionally, a program manager needs to communicate program vision and articulate benefits of the program oversight. At the same time, a program manager should be engaged in the low-enough level of details to be able to identify program and component risks. In contrast, a project manager has a narrow focus on the project at hand.

The program manager manages horizontally across the functional projects involved with the program. The program manager ensures that the cross-project work effort remains feasible from a business standpoint and realizes benefits. The goal is to leverage return on investment and control not available from managing projects separately, helping organizations to achieve strategic results. In contrast, the project manager manages only vertically.25

A program manager drives a program to execution using a top-down approach that includes setting up the program structure and implementing it on a program level, and executing it on a component level. If the structure is not working at the component level, a program manager implements changes on a program level and cascades them down to the component level. In contrast, a project manager applies the bottom-up approach to project management by planning and executing project phases.

Developing Soft Skills

As was mentioned earlier, a program team usually includes members from different departments within the organization who rarely report directly to a program manager. To successfully lead a team, a program manager needs to have soft skills, including an ability to influence, prioritize work, facilitate, trust instincts, push back, and be politically savvy.

Influencing

The influencing traits of a strong program manager include being socially adept in interacting with others in any given situation, having the ability to assess all aspects of information and behavior without passing judgment or injecting bias, and being able to effectively communicate your point of view to change an opinion or change the course of action.26

A program manager leading a virtual team operates in the environment with no physical and social presence, and faces the additional challenges of cultural and language barriers. To be able to influence in the virtual program environment, a program manager needs to have a high level of emotional intelligence. A program manager needs to be able to read between the lines and be aware of the virtual team dynamics. And, through effective communication, a program manager needs to influence decisions and motivate a program team.

Prioritizing

Prioritization of work begins with program core assumptions validation with the stakeholders and program governance body. If assumptions are incorrect, it is possible that program priorities will be incorrect. For example, if cost containment is the highest priority for a program, then a program manager must be emphatic about staying within the financial constraints. If technological leadership is the highest priority, a program manager needs to keep the team focused on technical aspects of a program. The ability of a program manager to focus project team work on the highest priority for a program is crucial for delivering intended program benefits.

Often, team members manage multiple, and sometimes conflicting, priorities. A program manager needs to be able to prioritize work for himself or herself and the team members. As programs often have a complex structure, a program manager needs to ensure that the time is spent on value-added work and the waste is minimized.

Facilitating

A program manager needs to have good facilitation skills to help multiple stakeholders, customers, clients, and team members to communicate and collaborate effectively. Good facilitation skills help to ensure that relationships between team members occur as needed—productively. Core facilitation skills include the ability to draw out varying opinions and viewpoints among team members to create a discussion and collaboration boundaries, and to summarize and synthesize details into useful information and strategy. Other beneficial facilitation skills include using personal energy to maintain forward momentum, being able to rationalize cause and effect, and helping team members stay focused on the primary topics of discussion and collaboration.27

Trusting Your Instinct

Among the valuable soft skills that a program manager should develop is the ability to trust your instinct. Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “Trust your instinct to the end, though you can render no reason.” In simplified terms, if you feel that something is wrong, it probably is. For example, if requirements review shows incompleteness that may result in failure during execution, start by conducting a detailed review. And, if an initial conclusion about requirements incompleteness is confirmed, revert by bringing the team back to the drawing board. Ability to trust your instinct is based on the program content knowledge.

Pushback

While executing a program, a program manager may come across situations that require pushing back. Power to push back on something that does not seem right should be based on in-depth program content knowledge. An example may be a need to push back on approval of a document if it does not meet quality standards or has incomplete content.

Being Politically Savvy

In addition to understanding the organizational structure, the program manager needs to be politically savvy to navigate politics within it effectively. Company politics are a natural part of any organization, and the program manager should understand that politics is a behavioral aspect of program management that he or she must contend with to succeed. The key is not to be naïve and to understand that not every program stakeholder sees great value in the program. A program manager must be politically sensible by being sensitive to the interests of the most powerful stakeholders, and at the same time, demonstrate good judgment by acting with integrity. The program manager must actively manage the politics surrounding his or her program to protect against negative effects of political maneuvering on the part of stakeholders and to exploit politically advantageous situations. To do this, it is important that the program manager possesses both a keen understanding of the organization and the political savvy necessary to build strong relationships to leverage and influence the power base of the company effectively.28

Proficiencies Align With the Organizational Structure

The skills and competencies of a company's program managers need to align with how program management is implemented and the roles they are expected to perform.29 Organizational structure defines the program manager role and, subsequently, the proficiencies needed to be successful in it. In a project-oriented organization, a program manager mostly has an administrative or facilitative role. In this role, a program manager spends, at most, 20% of the time leading a program, and between 80% and 100% of the time executing program operational management tasks. Proficiencies required for this role are limited and do not include all listed in the program proficiency framework.

If an organization becomes program-oriented, a program manager role expands, requiring additional proficiencies to support the transition from administration-focused to business-focused program management. In the program-oriented structure, a program manager has an integration or business role. In this role, a program manager spends 60% to 80% of the time leading a program and 20% to 40% of the time executing program operational management tasks. To succeed in this role, a program manager needs to develop all proficiencies included in the program proficiency framework.

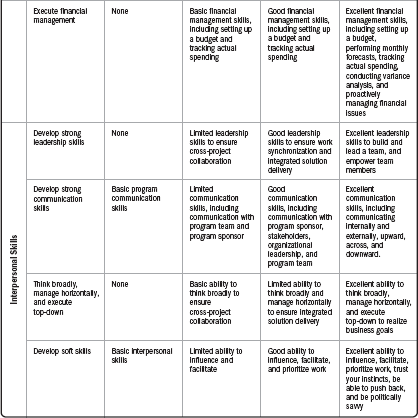

We will examine how proficiencies in the program proficiency framework change between project-oriented and program-oriented organizations, as outlined in Table 2-2. We will describe proficiency level using the following ranking: none, basic, limited, good, and excellent.

Organizations can strengthen program strategy alignment and increase benefits delivery as the program management function moves to the right along the program management continuum toward the program-oriented organization. Programs are tightly linked to organizational business strategy and serve as the strategy implementation mechanism to realize the business goals. In the business-focused culture, organizational hierarchical command and control are replaced by empowerment and accountability on the part of the program manager.30

A program manager's ability to lead a program is dependent on program infrastructure, (e.g., a system that supports program management, and tools that aid in monitoring program health). Program infrastructure enables a program manager to execute program operational management tasks quicker, focusing the majority of the time on leading a program, delivering to the strategic objectives, and becoming a trusted advisor and a subject matter expert.

As the organization moves from project-oriented to program-oriented, a program manager spends more time leading a program and less time executing program operational management tasks. To succeed in the complex organizational environment, a program manager needs to have various program proficiencies, and program proficiencies expand when organizations move from a project-oriented to a program-oriented structure, enabling a program manager to operate as a business program manager or a program CEO.

A program typically has a large and complex structure that includes multiple components. A program manager also manages the expectations of external and internal stakeholders. To operate as a program CEO, a program manager needs to have three main modules, which include an organizational structure that empowers program managers to lead, a program infrastructure that enables a program manager to lead, and a program proficiency framework that enables a program manager to succeed, as shown in Figure 2-5.

Comparison of Program, Project, and Portfolio Manager Roles

A program manager needs to clearly understand his or her role as well as the roles of portfolio and project managers. Understanding each of these roles is critical for achieving the successful collaboration necessary to maximize program benefits.

In the preceding sections, we defined a program manager role, examined what empowers a program manager to lead, what enables him or her to lead, and recorded a program proficiency framework that enables a program manager to succeed. Now, we will compare the program manager role with portfolio and project manager roles to gain a clear understanding of what each role does and how these roles interact.

Using the call center's process improvement program as an example, we will illustrate the relationship between a program, portfolio, and project. The call center's process improvement program is set to improve call response quality and decrease call response time. The program structure includes subprogram one, which consists of two projects: Project one improves call response quality, and project two decreases call response time. The program also has an implementation project three: Implement projects one and two in all call centers. Additionally, the program includes operational management activities, such as manage program costs and risks, manage links between projects, and coordinate and prioritize resources across projects.

The call center's process improvement program is included in their portfolio. The portfolio executes the process improvement program and conducts the call center's audit. And, similarly to the program operational management activities, the portfolio has operational management activities, as shown in Figure 2-6.

A program manager role includes setting up the program structure, overseeing program execution, monitoring risks, and carrying program profit and loss responsibilities. A project manager role includes managing projects and carrying responsibility for project execution on time and on budget. A portfolio manager role includes identifying, prioritizing, authorizing, managing, and controlling projects, programs, and other related work to achieve specific strategic business objectives.

Using portfolio, program, and project structure and the relationship between them, we can compare the roles of portfolio, programs, and project managers, as presented in Table 2-3.

Portfolio, program, and project manager roles are distinctly different, as evident from the analysis presented in Table 2-1. A portfolio manager focuses on selecting the right programs and projects, prioritizing work, and leveling resources with an objective of maximizing the economic use of resources within the portfolio. A program manager ensures alignment of multiple projects with program goals, and integration of cost, schedule, and effort. A project manager focuses on project scope, schedules, resources, and risk management.

A program manager closely works with the portfolio manager on project prioritization, resource acquisition, and risk escalation. A program manager also receives guidance from a portfolio manager on program structure, resources, and execution. Portfolio and program managers work closely together on portfolio and program process improvement efforts.

A program manager guides project managers on project execution, delivery on time and on budget, project quality, and risk escalation. Program and project managers work closely on process improvement initiatives to improve project execution mechanisms, tools to monitor project progress, and quality checks for project deliverables.

1 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Transitioning to program management. PM World Journal, 3(9), 1–3. Retrieved from http://pmworldlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/pmwj26-sep2014-Martinelli-RaschulteWaddell-Introduction-to-Transitioning-to-program-management.pdf

2 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons, Inc.

3 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Transitioning to program management. PM World Journal, 3(9), 1–3. Retrieved from http://pmworldlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/pmwj26-sep2014-Martinelli-Raschulte-Waddell-Introduction-to-Transitioning-to-program-management.pdf

4 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Transitioning to program management. PM World Journal, 3(9), 1–3. Retrieved from http://pmworldlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/pmwj26-sep2014-Martinelli-Raschulte-Waddell-Introduction-to-Transitioning-to-program-management.pdf

5 Blomquist, T., & Müller, R. (2004). Program and portfolio managers: Analysis of roles and responsibilities. Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference (11–14 July), London, England.

6 PMI. (2010). What does it take to be a program manager? Established veterans advise up-and-coming project managers on how to make the jump to program manager. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

7 PMI. (2008). The standard for program management – Second edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

8 PMI. (2017). Who are project managers? Retrieved from https://www.pmi.org/about/learn-about-pmi/who-are-project-managers

9 PMI (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

10 Written in collaboration with Russ Martinelli, co-author of the book, Program management for improved business results. (2014). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

11 Lovelace, J. (2016). Interview. MsPM, PMP, PgMP, Product Launch Management Advisor at Eli Lilly and Company.

12 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

13 PMI. (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

14 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

15 PMI. (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

16 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

17 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

18 Stuckenbruck, L. C. (1979, September). The matrix organization. Project Management Quarterly. Retrieved from https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/matrix-organization-structure-reason-evolution-1837

19 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

20 PMI. (2013). The standard for program management – Third edition. Newtown Square, PA: Author.

21 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

22 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

23 Merrick, A. (2015). Allied forces. Retrieved from http://www.pmi.org/-/media/pmi/landing-pages/business-analysis-tools-silverpop/pdf/allied-forces-project-management-business-analysis.pdf

24 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

25 PMI. (2010). What does it take to be a program manager? Established veterans advise up-and-coming project managers on how to make the jump to program manager.

26 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

27 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

28 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

29 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Program management for improved business results. (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

30 Martinelli, R. J., Waddell, J. M., & Rahschulte, T. J. (2014). Transitioning to program management. PM World Journal, 3(9), 1–3. Retrieved from http://pmworldlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/pmwj26-sep2014-Martinelli-Raschulte-Waddell-Introduction-to-Transitioning-to-program-management.pdf