CHAPTER 3

The Economic Theories Underlying Sales Ethics

Virtue is a habit, a practice and you get to be the kind of person you want to be by trying to act that way, by really focusing on behavior.

Why Read This Chapter?

We are going to discover the theories that will rehabilitate the role of ethics, as we defined it at the outset of this book, within the realm of business. We will also see how the figures confirm that not only is it economically viable to be ethical but also that the results obtained will satisfy the capitalist logic of profit maximization. To this end, we will analyze the theories of Nash, Maslow, Arthur, and many others, and give examples taken from our own experience.

At the end of the chapter, you will find exercises that encourage you to reflect on the themes and theories presented and help you to place them in the context of your own everyday experience.

People who talk about ethics in business run the risk of either being labeled as do-gooders, or charged with using arguments that are clearly common sense but cannot be feasibly applied in everyday business dealings when faced with the harsh realities of market competition. In conversations between salespeople, ethics is often seen as a nonessential extra; it’s almost as if we can only consider relationships once we have achieved the turnover and profits that our organization requires. As Leigh Hafrey of MIT Sloan Business School noted when gathering case studies for his book The Story of Success: Five Steps to Mastering Ethics in Business, this attitude is widespread on both sides of the Atlantic. The basic idea behind this view of ethics is that you must first endeavor to ensure your own survival, that is, make sure you generate profit, before considering the ethics of your negotiations. This outlook means that ethics would be denied any strategic part in the actual negotiation phases, and when putting together a commercial transaction whose outcome is determined by completely different behavior, any introduction of ethical practice would be no more than the icing on the cake!

The aim of this book is to restore strategic value to ethics by contributing ethical elements at every stage of negotiation with your customer. The main goal here is not to create a pleasant and honest relationship but rather to increase the value generated by each transaction!

When we restore market value to ethical practice, it is also an attempt to move beyond the conflict of interest that would seem to plague all relations between buyer and seller. In our opinion, this conflict arises from a limited interpretation of the principle of profit maximization that has informed modern economics ever since its first appearance.

In his treatise, The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith claimed that self-interest ensures greater richness both at an individual level as well as globally across the market. Smith’s theory was based on the presence of a self-regulating mechanism which he referred to as “the invisible hand” which would counterbalance any injustices and pressures that arose when individuals were involved in pursuing the greatest profit.1 However, the Scottish economist did not clarify how this mechanism would actually work and merely stated that the selfish pursuit of personal interests would also trigger an improvement of the general conditions common to the actors in the market.2

In any sale, the seller’s desire to gain maximum profit corresponds to an equal and opposite need by the buyer to maximize their purchasing power. Thus, if we were competing in a market that applied to the letter the theories of classical economics, which relies too heavily on a short-term vision, we would witness a tough fight between the interests of those who sell and those who buy. In such a scenario, ethics is not only useless but also potentially harmful because it could distract players from what should be their natural primary goal when bargaining.

Hence, to restore strategic value to ethical behavior, we must show that it is a prerequisite for the maximization of individual advantage. Only then can we rightfully place ethics among the assets required by any salesperson. If we treat ethics as an element that is not part and parcel of bargaining technique, we would be relegating it to the role of a luxury item suitable for the few sellers operating in particularly sensitive areas such as nonprofits. Our goal instead is to restore its rightful place in all kinds of business relationships, not as an optional extra, but as a vital component, that is perfectly in line with the market logic and the creation of individual well-being. If we succeed in doing this, we will convince sellers to adopt ethical behavior, not only by appealing to their sense of morality, their good intentions, or the fairness of the way they act, but also by invoking a much more powerful force, that is, an integral part of human beings’ struggle for survival: the increase of value for themselves.

Incremental Negotiation

To rehabilitate ethics, by assigning it a specific role in the mechanisms of the market, we will refer to studies carried out by John Nash on strategic games. The Nobel Prize winner was able to prove that if applied to the letter in every single period of interaction, Smith’s form of competitive strategy did not always lead to the highest payoff:3 certain forms of cooperation are in fact able to ensure a greater profit both globally and at the level of the individual actor. In fact, Nash’s studies helped to reveal the dangers of an action driven solely by short-term self-interest, thus encouraging a new approach to game theory that has made it possible to demonstrate how the strategic value of cooperation emerges when there are repeated exchanges. Thus, if we pursue the interest of the group as well as personal interests in each period, at the end of the game more benefits will accrue to each individual.

To illustrate the logic behind this approach, we will give a simplified explanation of the theory of repeated strategic games. We apologize in advance to experts on the subject for any inaccuracy or oversimplification resulting from our endeavor to make the concept clear and easy to follow for those unfamiliar with economic studies.

In repeated interactions or those that take place with the actors living within a cohesive social group, the opportunistic strategy to maximize short-term payoff does not produce an optimal result. In fact, if we try to maximize profit in the short-term to the detriment of the other party, they will no longer be willing to interact with us a second time, having been cheated before! Worse still, they may influence the social group within which the exchange takes place, so that the group’s members are reluctant to interact with us. This circumstance has two negative consequences that could compromise our future profits: failure to repurchase, with possible loss of customers, and bad reputation with the extreme outcome of exit from the market. Sellers who can maximize benefits not only for themselves but also for their customers encourage further interaction. The sum of all the new interactions makes up the cumulative returns that are far superior to those obtainable by acting in a short-term logic.

If I act in order to maximize value for both myself and the other actor, I help to create dynamic forces within the buyer–seller relationship that can fuel it or even multiply it by expanding the boundaries to include other customers.

To understand how these forces work, we will compare two negotiation strategies, one based on a short-term logic that we call one-shot negotiation, and the other designed for long-term interaction and defined as incremental negotiation. We will assume that our seller, even when competing for short-term maximization of value, does not adopt a technique that will cause his customer to lose out, but will ensure a payoff exactly equal to his own. Note that we are not talking about a seller who deceives his customer but a seller who bases the exchange on short-term numerical equivalence. We do not want to contrast a seller who behaves improperly with one who behaves properly, but to focus on economic behavior rather than morality. Being ethical in business relationships involves not only behaving properly, but also acting strategically.

Suppose a customer is willing to pay $100 for the goods and our seller is offering a product that correctly and comprehensively covers the customer’s requirements and can be, in fact, valued at $100. This exchange would take place in a way fair to both parties in the negotiation. From this moment on, the customer and the seller, both perfectly fulfilled with the transaction, will have no further claims on each other. In fact, we can define their mutual satisfaction, which is the consequence of perfectly balanced exchange, as static. From the observation of natural phenomena, we learn that the only systems in static equilibrium are dead systems. The balance in nature is in fact always dynamic because life is a mechanism that involves movement. In sales, it is equally important to keep the relationship with our customer alive and pulsing, so we need to insert elements that can activate movement and thus further exchanges. How do we go about it?

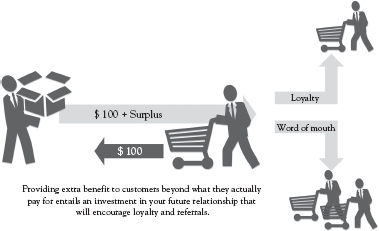

If, instead of offering the customer a value exactly equal to that for which he has paid ($100), we were to offer him something of higher value—for example, 30 percent more—this would lead to an imbalance in the negotiation equilibrium4 that could generate a forward movement in the relationship between our customer and us. This difference will commit the customer in interacting with us again and making further purchases in accordance with the law of reciprocity, or in enhancing our reputation in their social group. Both circumstances would create new opportunities for sales that, over time, would repay the surplus (the 30 percent difference between what was paid and what was received) that we initially supplied to the customer (see Figure 3.1). This is why our friend Daniele Prioli, one of the most talented salespeople we have ever met, says that a good sale requires sellers giving a customer a little more than they earn, even at the cost of ending up slightly poorer after the first deal. When we met him back in 2003, Daniele was a freelancer and had not yet set up Geocom—a company specializing in geomarketing and contact management—with Carlo Renzi. Even then, both men operated according to this unwritten law that we call incremental negotiation, and which could be simply summarized as giving customers more than they pay for! We contacted these two men for market research and received a great deal more: Daniele and Carlo became active partners for us, coming to meetings and offering advice, as well as providing useful contacts to increase our sales and being open with us and enriching our relationship.

Figure 3.1 Incremental negotiation

Undoubtedly, all the time and energy invested on the project by the two consultants was not immediately repaid, but this apparent loss was in fact an investment: Over the following years, we have paid for further services from them and spoken well of Geocom with many colleagues and potential clients, helping to fuel their success.

Yet one question remains: If the seller is forced to offer more than what they get to maintain a lively and active relationship with the customer, does this not go against the maximizing of profit in the short term?

To give you an answer, we want to introduce another theory here to support our idea, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which will help us to take the full range of the customers’ needs into consideration and not just their material needs. If we were to think in purely materialistic terms, we would fall into the error of pitting incremental negotiation against the rules of classical economics. By analyzing what the surplus offered by the salesperson is, in the context of Maslow’s theories, we will show that this negotiating method does not in fact contradict the theory of maximization of profit, but rather enhances it.

When we explained the concept of value in the previous chapter, we broadened its meaning beyond the simple concepts of best price and best return as not everything that is customer value and seller value can actually be measured in material terms. The intangible aspects that contribute to increased value include attention, listening, suggestions, knowledge exchange, helpfulness, and services.

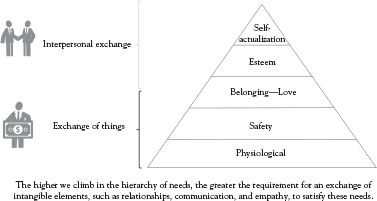

The American psychologist Abraham Maslow organized human needs into a pyramid of five levels of hierarchy that we will apply to the consumer, according to Figure 3.2.

The first category that, according to Maslow, we try to meet is our physiological needs; we then move onto the next levels, which become progressively more complex and sophisticated. If we transpose this hierarchy to the economic environment, we can see that the more mature the market, the more the customer choice will be determined by the needs at the summit.

Let’s now go back to Renato, our salesman, and his customer who is interested in buying a car, to see how Maslow’s theories can be applied to Sales Ethics.

Figure 3.2 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

If I decide to buy a car, the physiological need that my purchase aims to satisfy is getting around. According to Maslow, I will make sure that the car can move (that it has wheels and an engine) and that I can do so safely (e.g., I want to know if it has ABS and airbags). My next consideration will involve making a purchase coherent to my social group to ensure that I am accepted into a specific group (this will involve considerations regarding the make and model of car, reflecting its prestige and image). Up to this stage, all my needs can be met by the tangible features on offer, which correspond to a definable purchase price. Let’s now step into the salesperson’s shoes. We soon realize that the price we are able to ask our customers will be regulated according to the specifications listed beforehand. If the car travels faster (maybe it has a more powerful engine) and is safer (it is equipped with airbags or more advanced safety systems compared to other models), or it is produced by a luxury brand, this will influence its price. The price is therefore still an efficient regulatory mechanism on the trade between buyer and seller. What elements of the product, then, will make the customer feel esteemed and actualized during the negotiations? For instance, if customers have to choose between two sellers of the same brand offering them the same model at the same price, what will guide their choice?

The needs Maslow places at the highest levels are related to the increasingly intangible components of the customer–seller relationship, for which no exact price can be set. If a salesperson is able to fulfill their interlocutor’s need for esteem and contribute to the customer’s actualization, they will have satisfied the needs that top the hierarchy, by actually offering more than any rival salesperson who has not looked beyond the material aspects of the exchange. However, since these intangible elements of the offer are not regulated by the price mechanism, our seller might be at a disadvantage. If, from a material point of view, the seller is offering nothing more than that of a rival, his or her commitment in terms of the relationship—to make the customer feel valued, rewarded, and fulfilled—cannot be immediately quantified in monetary terms!

We can easily realize that this nonmaterial surplus is the 30 percent extra than what we noted before, which could trigger the forces that encourage not only the current sale but also new trade with the same customer (loyalty) and the opening of new business opportunities (word of mouth). The subsequent purchases by this customer and the new relationships developed, thanks to the enhancement of reputation, are the payment the seller will receive in exchange for the surplus time initially offered to the customer. On one hand, this repayment is intangible, but then it brings a concrete benefit ensuring compliance with the principle of profit maximization (which in the short term appeared compromised). On the other hand, it involves the higher levels in the hierarchy of needs, whose satisfaction is especially strategic in mature markets where products show very little variation as regards technical characteristics and prices.

Exercise

• What extra can you offer your customers? Ask yourself what more you can offer your customers that will not involve an immediate payoff. How can you upset the balance in favor of your customer? To focus on this aspect and come up with some answers take another look at the needs set out in Maslow’s hierarchy or reconsider the intangible components of your offer system.

Reciprocity and Relationship Styles

There are many theories aimed at highlighting the strategic value of relationships, such as Shapiro’s theory of reputation5 and Freeman’s stake-holder theory.6 You can find hundreds of texts dealing specifically with this topic if you want to read further for detailed explanations. We intend to give a briefer outline.

What interests us here is to emphasize the relationship between reputation, negotiating efficiency, and reciprocity style.

The fact that we must take reciprocity into account to build a solid reputation and improve the efficiency of our relationships has been brilliantly demonstrated by Adam Grant in his book Give and Take.

Grant distinguishes three types of reciprocating behavior, corresponding to three styles: the taker, the giver, and the matcher. As the name implies, takers are people who tend to take more than they give. They conceive relationships in utilitarian terms, considering their own interests paramount and not feeling in any way bound to reciprocate after receiving something from someone else. To put it briefly, these are the proverbial opportunists.

The matchers, on the other hand, are aware of the laws of reciprocity: They know that before you take it is often necessary to give, and that if you fail to reciprocate you are acting unjustly. However, their actions are not totally disinterested, and they are willing to make the first move in an exchange only when they know that their customers will be able to reciprocate. They are experts in reciprocity and their apparent generosity is always dependent on receiving a direct and immediate comeback.

The third type is that of the giver. These people give to others without addressing the problem of receiving something in return in utilitarian and immediate terms. Their goal is social, that is, they want to help increase the value and well-being of the system to which they belong, in the certainty that they too will enjoy the benefits. Their generosity is also rewarded by the personal satisfaction they feel in helping others.

Grant has discovered and demonstrated through studies and analyses of real cases that not only is the giver’s cumulative benefit greater in the medium to long term when compared to the other two styles of behavior, but also that these people build continually, expanding social networks that are characterized by strong and empowering relationships.

Contrary to what happens to the taker, whose behavior erodes social ties (people tend to move away once they discover they have been used), or to the matchers, who are forced to limit the size of their network to include only those parties able to reciprocate, the givers weave extended networks of relationships without expecting any immediate return.

Moreover, the givers may also activate new latent givers by inspiring them (thanks to their altruistic example) to behave in the same way with other people and hence further extending their contacts and relationships. Their network thus grows exponentially and their positive reputation travels widely and swiftly.

Contacts, stable relationships, and positive reputation are the fundamental elements of business success. The proper use of the principles of reciprocity, which inspires the behavior of the giver, would seem therefore to be one of the most powerful tools you have at your disposal to enhance your results, broaden your customer portfolio, and turn you into a successful ethical salesperson. Confirming the saying what goes around, comes around.

Expanding the Pie: Increasing Returns

Another theory worth looking at to gain a better understanding of the transformation of competitive dynamics in modern markets is that of increasing returns proposed by W. Brian Arthur,7 which we have reworked to suit the context of Sales Ethics.

According to this view, when choosing their competitive model, the majority of companies assume that markets are limited by two factors: the scarcity of raw materials needed for production, and the geographical dimension on which a set of costs depend (logistics and trade, for example). These two constraints are such that the total profit available in a single market has a finite value, almost a given constant. The variable, influenced by business strategies, is the percentage of the total profits of the particular market in which they operate that they can get grab for themselves. Companies compete to raise returns by adopting opportunistic behavior justified by the scarcity of raw materials and the limited size of the markets. This predatory behavior, however, accelerates the erosion of the total profit and further restricts the wealth available from the market (competitors tear customers away from each other), increasing competition for the supply and potentially leading to an implosion of the industry.

Yet what would happen if we had unlimited access to productive resources and could broaden the geographical boundaries of our market? The answer that Arthur’s model proposes is obvious: The total returns available to all the actors would start to climb and expand and would once again become a growing variable influenced by the single business strategies. By increasing the wealth available to everyone, opportunistic competition involving preying on rivals’ customers and lowering your own profit margins would no longer be necessary. But are there markets where this is possible?

When he asked himself whether all markets were indeed characterized by scarce resources and set geographical dimensions, the American professor discovered that there are some market areas in which these two constraints are much weaker. For example, if we sell creative ideas through the Internet, the scarce resource that we must procure is primarily our imagination and the geographic dimension of our potential market is the entire World Wide Web.

In this case, the limited resources and geographical constraints are much less binding than in a traditional business, so that predatory competition is unnecessary. On the other hand, collaborative and relational strategies that trigger forces to expand market boundaries—that are in any case fuzzy—will play a key role. The market will grow and the profit margin available to all competitors will grow with it.

This is the business model on which giants like Microsoft or Facebook (at least initially) based their strategy. They chose not to enter into direct competition with any of their potential rivals but rather to collaborate with them to create a market that did not previously exist and hence expand what had hitherto been a very limited niche market.

If we were to imagine the market as a pie, in the first case (limited markets) the only choice would be to elbow out the competition to get the biggest slice, but this would mean that the struggle to get our slice would be even harder the next time as the part left over would be proportionately smaller. In the latter example, however, we would have a pie that could be expanded to satisfy our own appetite and we could even offer some to others.

For a better understanding of this concept, we will use an example from our professional lives.

As we mentioned earlier, we have a counseling and training agency called Passodue. The resources that are scarce in our production system are our time, our knowledge, and our ideas, all of which require no competition with other professionals to be produced, as they are all purely personal. On the other hand, there is no direct competition for our offer, because if you think about it, even if one of our courses were to have exactly the same program as that of a colleague-competitor, the classroom interaction with students and our way of explaining the content would be different. Anyone who has participated in a training course even once in his or her lifetime knows how the quality of learning changes, depending on who is teaching. Therefore, we are actually working in a market with a low level of direct competition that is uncrowded and with sufficient scope that has noncompetitive access to scarce resources. What sense would there be in adopting opportunistic strategies in such a market? Why should we try to lure customers away from our colleagues by adopting aggressive pricing strategies that in the long term would erode our margin and the total wealth of the market? Such a strategy would lead to a competitive model and decreasing returns with bargaining tactics based around the offer of ever-lower prices.

The strategy we have adopted for Passodue is based on our relationship with clients and other professionals in the sector, which triggers virtuous mechanisms that have led to increased opportunities and visibility. By investing in relationships, we have acquired loyal customers who actively promote us by speaking highly of our work with other potential buyers and often participate in the construction of content for our courses.

We also collaborate with our supposed competitors to promote the demand for a range of skills that complete our offer system, as well as broadening the base of the market. In fact, through a joint effort we raise awareness among companies of the possibilities available in our branch of training and consultancy. We organize meetings with our colleagues, friends, and competitors to explain the changes taking place in business and their impact on management. These joint activities are designed to expand the market, so that more and more people feel the need to buy training and consulting services. It does not matter if the companies initially purchase services from our agency or from someone else. If the market is growing, there will be more demand and the profits available to all will increase; growth will just depend on presenting a clear offer and a distinct, clearly comprehensible identity based on values that help new customers to navigate between the different buying opportunities that an expanding market offers.

While in markets characterized by diminishing returns it is essential to maximize gains in the short term by optimizing processes to make better use of expensive and scarce resources, in markets where profits follow an upward trend the strategic focus is moved forward. The idea of winning single battles in a war that will eventually be self-defeating (returns will decrease and reduce the profitability of that market) will be replaced by a strategy focusing on overall growth and expansion. Since we have to focus on our path over time and not on one-shot outcomes, we must clearly define our objectives from the outset and make them so compelling that they attract new traveling companions to support us on our journey; these fellow travelers will help us blaze a trail that will attract new customers and opportunities. However, working together and investing in relationships in these markets is not enough, it is also essential to focus on communication and image, the components that clearly convey our goals, our values, and our vision.

Our ability to communicate effectively and our style in relationships will be the factors that determine the launching of a pledge or challenge that the consumers and competitors will notice, which will, in turn, lead to an expansion in our market.

When Bill Gates told the world he envisioned “a computer on every desk,”8 he still did not know how this would come about; but he did know that he would not be able to achieve it alone. The decision to concede the Windows license to new developers and to involve the hardware producers (who at that time were also producing software and were technically his competitors) meant that over a few years he redefined the style of consumption in that market and, subsequently, achieved hitherto unimagined success as an entrepreneur.

Jay Coen Gilbert and his B Corporations9 are also showing how you can get results by acting in a different way on the market, through involvement of producers, consumers, and competitors in the construction of a community that produces shared value and thus helps to expand the pie for all actors in the market.

Some years ago, there was a great entrepreneur in Italy who tried to work within the logic of the market but with a radically new approach, replacing the idea of profit with that of value and enhancing the social role of his enterprise. This man was Adriano Olivetti,10 founder of the company that bore his name. Although his message has received little international attention, it is timelier than ever. Olivetti believed strongly in the importance of sales and his companies had the highest ratio between salespeople and employees ever recorded in Italy: For every 100 employees, at least 30 worked in sales-related jobs.

Let us briefly review what we have learned from W. Brian Arthur’s theory of increasing returns:

• Focus on nonrival components of the offer system, the ones where our differential value is more obvious or for which there is no real competition of supply—often related to intangible aspects such as style of relationship or creativity.11

• Extend your network of relationships by considering customers and competitors as partners, coproducers of value, and interact with them to extend the boundaries of the market.

• Clarify your goals and values through appropriate communication, so that your identity and your differential value are quite clear.

• Invest heavily in providing good information to customers, to educate them to understand the value of your offer system, including its intangible aspects.

• Think in the medium to long term as well as the short term, without trying to capitalize immediately, at all costs, on every single action. A market based on the dynamics of increasing returns primarily requires investment and a vision of the future.

In the classroom, we find that participants always want further discussion on W. Brian Arthur’s theory as it gives rise to a number of concerns. We will analyze the two main concerns here and leave further explanation to the section of FAQ:

• Markets are interrelated and on examining the ties between them we will find at least one characterized by scarce resources, geographical limits, and decreasing profits that can block growth in our sector as well.

• All resources are in a sense scarce. Time and ideas, for instance, are not limitless.

It is fairly simple to answer the first objection. Even if we suppose it is true that when we go back along the line that links the various markets together, we will eventually run into a traditionally based decreasing returns model this does not mean that our competitive system should adapt to it. To clarify this, let’s go back to our example of Passodue. It is true that we work for companies operating in traditional markets, where resources are scarce and where it is necessary to increase costs to move beyond geographical boundaries. Some of our clients compete against each other in an opportunistic way by trying to secure the lion’s share of the total profit to which they have access in a specific market. Does that mean we should adopt a similar strategy to be in keeping with them? The fact that markets are connected does not mean that the competitive model to which they refer is the same. There is hence no justification for adopting a similar strategy.

As far as the second point is concerned, the observation that all resources are scarce in some way is correct. However, again this does not mean that competition is the best way to tackle or reduce this shortage. If I produce bolts, metal will be the scarce resource. Price will be my bargaining tool to get hold of larger quantities of metal and I will offer my suppliers a more advantageous contract to have greater access to the required raw materials. Consequently, however, I am cutting into my profit and I will need a bigger slice of the market if I want to make gains, triggering the mechanism of erosion that we described earlier. On the other hand, if the scarce resource is my time and my ideas, where can I turn to extract more from my head? With whom am I in competition?

In our case, we could expand time and ideas by taking on new staff, but this would change our business model, transforming our activity as consultants and trainers to suppliers of services provided by others. If, despite this, we wanted to expand the team, we would select people who shared our goals and our vision. Other companies would adopt different selection criteria and choose different people. It is thus clear that there is no real direct competition for the supply of limited resources.

The closer the strategic value of an offer system is to intangible components, the more likely we are to operate in markets characterized by the increasing returns competitive model postulated by W. Brian Arthur. Markets involving training, counseling, communication, creativity, and services in general are the ones where it is useful to adopt this competitive model, based on relationships and cooperation. However, there is another aspect that makes the theory of W. Brian Arthur important; in fact, when discussing Maslow, we stated that in mature markets the needs at the top of the hierarchy are of crucial strategic value. These less tangible needs can only be satisfied by the more intangible components of the offer system such as communication, reputation, and relationships, which do not depend specifically on scarce resources or competitors. This changes the competitive model even in mature traditional markets, bringing them closer to the dynamics of increasing returns markets.

Finally, we would like to clear up a possible misunderstanding: The strategic models based on relationships and reciprocity are no simpler than those based on opportunistic strategies. It is certainly not enough to be personable or friendly to excel. The fact that you only achieve success after following a longer course and not by winning a single battle makes this choice challenging and decidedly risky.

M. Gladwell wrote an interesting book entitled Outliers: The Story of Success12 where he analyzed the personal stories of several successful people, including Bill Gates, and reached the conclusion that it took them on average 10,000 hours of personal application and commitment to reach the heights of their professions.

This begs the question: Could you dedicate this much time to a job if you did not love it?

Whatever the competitive model or strategy that we adopt to achieve our goal, if the effort is too great a strain, we will never reach our objective. A colleague of lesser talent who loves the sport would beat even a talented and well-trained marathon runner who hates to run.

Reciprocity, as we saw at the beginning of the chapter, is important to feed our gratification along the way: It allows us to receive a portion of the result in advance and conditions our motivation. If we enjoy the journey and not just the final destination, we can consider the identity conflict in a different light. Often we are willing to put up with this conflict under the misapprehension that the effort of acting against our values will be repaid by our future earnings. Consider, though, that often you will not receive any payment, income, or commission until a long time after you have striven to close a deal, and your motivation could vanish before this. If we act in an ethical manner in accordance with our true nature, our returns will be immediate. From the moment when we find our customers and relate to them, we will be reaping part of the rewards as personal gratification and pleasure derived from this relationship. Without this motivating force, even the slightest effort becomes tiring and distances us from the final goal.

Italian newspapers recently carried an advertisement for the Opera San Francesco per i Poveri (an NGO that assists the poor), which called for donations with the words: “Be selfish, do good: Doing good is the best way to feel good.” We could paraphrase this by saying be selfish, be ethical with your customers: You will accumulate greater well-being and find new motivation to continue along the road to success!

• What are the noncompetitive components of your offer system? Write down what you really do well in your job or what sets you apart from your competitors. It does not matter if you only identify one element, the important thing is that you are sure you know the best way to do it and that you enjoy it and that it unequivocally represents you. Now ask yourself what kind of resource you need to accomplish this task. Consider whether it is predominantly ideas, creativity, or relational skills that mean you are not in direct competition with anyone else.

1 Smith (2012).

2 As clarified by A. Sen in his book On Ethics and Economics (1987), Smith’s thinking was probably misinterpreted and in the light of more recent studies it seem ungenerous to remember him only as the father of the theory of maximization of self-interest. We should note that Smith also wrote the treatise The Theory of Moral Sentiments (2010) which rehabilitates the role of morality, prudence, and understanding in economics. For the sake of simplicity, however, in our text, we refer exclusively to the Smith’s theories regarding the maximization of self-interest.

3 The classic example is the prisoner’s dilemma, which we briefly explain here, but that you may like to study further. Given the chance to reduce their own sentence by testifying against their accomplice, two prisoners end up accusing each other and both receive a heavier sentence thus worsening the outcome. As each pursue individual reward, the net result is less profitable than if they chose not to betray one another and hence served a punishment proportionate to the crime with no aggravating circumstances.

4 We use the term negotiation equilibrium to define the reciprocity mechanism within a negotiation that balances what we give with what we receive.

5 Shapiro (1983).

6 Freeman (2010).

7 Arthur (1996).

8 Microsoft mission statement in the mid-1980’s, “A computer on every desk and in every home running Microsoft software.”

9 A community of over 850 companies distributed in 28 countries and 60 industries that aim to redefine the meaning of success in business through a strict standard of social and environmental impact, transparency, and accountability. The B Corporations are working to improve the quality of the work and lives of their employees and their customers by adopting policies to create market value, not just profit. To learn more visit the website http://www.bcorporation.net.

10 Olivetti (2012).

11 Some time ago, the journalist Massimo Gramellini wrote in the well-known Italian newspaper La Stampa (2014), “We cannot escape the crisis by doing better the things that others already do. We can escape the crisis by doing, to the best of our ability, the things that only we know how to do.”

12 Gladwell (2008).