CHAPTER 2

The Key Concepts in Sales Ethics

Any sale involves multiple levels of achievement so you would have to parse the motives of both seller and purchaser, to arrive at a confirmation of happiness for either party.

Why Read This Chapter?

This chapter will first establish the key concepts of Sales Ethics that help you to fully understand and then implement the techniques of negotiation. These definitions will help you to reflect on your work, and will provide you with examples and suggestions to improve your efficiency. The discussion covers the following:

• Skills and abilities

• The product-service system or offer system

• The concept of value

• Sales

• Externalities and information asymmetries

• Reciprocity and cooperation

• Well-being and well-having

• The circle of trust

There are some useful exercises at the end of the chapter to apply these concepts in your work.

Skills and Abilities

For too long, selling was not considered a profession, so much so that there were no degree programs to prepare people for the practice of this activity, whereas all true professions require some sort of degree. You became a seller through a combination of talent, opportunity, and experience in the field. Hence, the image that we all associate with a salesperson is that of a strong personality with the gift of gab. Salespeople seem to be outsiders as regards rules and corporate hierarchy; in fact, though working for a company, they do not spend much time in the office, but in the car or in the field.

We can discuss the application of ethics to sales only if we consider it as an actual profession based on specific skills and abilities. Bearing in mind the definition we gave for ethics in sales, how can we answer the questions related to the efficiency of our commercial actions if it is not possible to identify a method of approach to the customer? How can we understand the amount of value created for us and for others without making the necessary checks? How can we balance our commercial action against the real needs of the client without having first conducted an analysis?

Analysis, methods, procedures, and checks are therefore at the heart of what we call the skills of the ethical salesperson.

Assumptions regarding the requisites for a career as a salesperson are now undergoing profound changes. Is a considerable dose of self-confidence and adeptness at communication still enough to determine the success of a salesperson? Are you really able to communicate and propose the most suitable product or service to your customers when you lack the ability to listen? Are there other colleagues whose work, directly or indirectly, influences your commercial success and are you able to work as a team with them?

We find the answers to these questions through constant, daily exercise aimed at developing your basic talents. By training in listening, empathic communication, and teamwork, Ethical Salespeople will develop the abilities needed to transform their profession.

We must also consider another often-overlooked aspect of the sales-person’s job, that is, the role of interface between two seemingly incompatible worlds: the company’s internal organization and the customer’s needs. We could say that a good salesperson sells twice, first to customers (who will be encouraged to accept the solution that the company has prepared for them) and secondly to the company itself, which will have to digest the demands of the customer. We commonly come across salespeople who complain of this role of interface, but the essence of our profession lies in our ability to enable customers and companies to communicate, and to aid both to create shared value! However, if we are in conflict or disagreement with our company, we will lack the necessary motivation and arguments to resolve the apparent conflict of interest that distances us from our customers.

By fusing skills and abilities, and including both in the scope of what we call the profession, we can overcome the identity conflict, the contrast between the professional and personal aspects of our lives that is created when our values as individuals contrast with what we feel forced to do as professionals. You cannot be a valid professional unless you are a valid person first, because what we bring to our work (behavior, ideals, and style in relationships) must necessarily be consistent with what we are. The barriers that we were taught to erect between our work and our private life are crumbling. The new sales professionals will not slip out of their salesperson identity at 6 p.m. to suddenly go back to being human for a night out with friends, but rather all the parts of what you are and what you do will fall naturally together. The fear that you are thus running the risk of your private sphere being swallowed up by you professional life is unfounded: If you love your job, and you do it with passion and feel it as an essential part of you, then it already coincides with the deeper you, and your mission as a human being. The dichotomy between professional relationships and personal relationships no longer makes sense. All our relationships involve us fully as human beings; the only thing that changes is the context in which they take place. Our soul, our essence, and our values never leave us, and if you are harboring an identity conflict, you will never be credible and effective in your dealings with the customer—this will undermine your motivation, your achievements and ultimately your confidence in yourself.

The Product-Service System or Offer System

Many salespeople are accustomed to seeing the company’s offer as a list of products and services, but are we sure we are only selling material or tangible items? The Sales Ethics approach is to broaden both our own focus and that of our customer to include alongside the description of what we will do for him, information on how we will do it, and hence, why we do it. If we perform this exercise backwards going from what (the object of our sales) to how (the services and agreements that accompany it) and then get to the why (our values and goals), we will be able to identify better the components that make up our offer.

We will discover that aspects such as our image, style, ability to communicate, as well as our choices and ourselves as human beings may be much more important for our interlocutor than the list of the product’s features. All these factors together define what we will call the product-service system, or the offer system (see Figure 2.1). If the product-service system is only partly developed, the customer will focus exclusively on material aspects and features such as the price.

The problem of providing only partial arguments plagues many of us sales professionals and occurs when we are not entirely aware of what we are offering, or worse, when we think we already know what will interest the customer. This approach shows that we neglect to present the arguments we assume the customer will disregard. Yet if you think about it, you cannot know in advance what will or will not interest a customer. During negotiations, it is important to devote time to analysis in order to fully understand who you are dealing with and what their needs are, so that you can present your offer by highlighting what is really important to them.

During training sessions if a seller comments “Our competitors sell exactly the same product, but at a lower price,” we help them to reflect on the fact that no two offer systems can be identical, although a salesperson may sometimes offer only partial or incomplete arguments, neglecting the differential element that can direct a customer’s choice. There is one thing in particular that will always differentiate your offer system from that of another seller even when the products, services, and prices are apparently similar: You are one of the main elements of the offer you are making to the customer, you are the feature that, above all, will guide the customer’s choice.1

Figure 2.1 Diagram of the offer system

What customers are looking for is not perfection, but the truth of your arguments: They want to understand to what extent you believe in what you are presenting.

Voltaire said, “The best is the enemy of the good,”2 indicating that our imperfections, our limits, and even our mistakes can hide a truth and richness that are valuable because they make us credible. So you can feel attractive with all your flaws and limitations, because these allow your customer to live a real experience and feel that the person in front of them is a human being and not someone programmed to play a part. You are the one guiding customers through the offer system and taking them beyond what you materially sell to the how and finally to why you are there. This is why your customer will choose you.

A few years ago, a company asked for our assistance in tackling an abnormal drop in sales that was limited to one particular area of the market. After analyzing their offer system and studying interactions with customers, we realized that the element being neglected in that specific area was human relations. The sales force and management working in that part of the market, in fact, were focusing too much on office activities (churning out estimates via e-mail, planning promotions, and drafting complex analysis reports) and were consequently devoting less time to direct contact with customers, failing to visit them as required. A comparative analysis also revealed that the main reason why customers chose to buy the company’s products was in fact the ability of sellers there to establish empowering relationships. The solution was to shift the focus back on building a relationship with customers, by increasing the quantity and quality of sales visits. The sales and profit margins then rose.

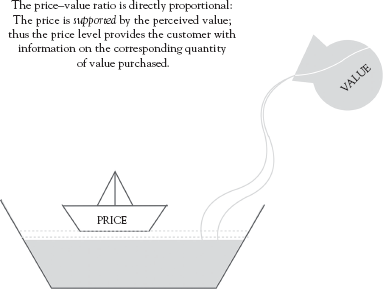

Figure 2.2 Price–value ratio

It is also crucial to remember that you yourself are an integral part of the offer system when you present the price. We will discuss this in detail in Chapter 5, but for now, we want to reveal that price and perceived value are two related concepts in the mind of the customer (see following Figure 2.2). If you respond to a request for discount by lowering the price, your customer’s perceived value3 of the entire offer system (of which you are a part) will drop immediately.

For all salespeople, the way in which an offer is presented is of the greatest importance if you are to align the value expressed in the proposal with the customer’s expectations. By working on your communication and style in relationships and, above all, on yourself, you will be able to redesign your offer and organize your arguments to maximize their effectiveness.

The Concept of Value

As we mentioned earlier when we defined Sales Ethics, the generation of value is the ultimate goal. It is therefore fundamental to clarify what we mean by this term and to define what it represents for the two actors taking part in the exchange:

• Customer value (and the network to which he or she belongs)

• Seller value (and the organization for which he or she works)

Traditionally, we associate the former with value for money; within a commercial exchange the customer seeks to maximize his purchasing power,4 so the cheaper the price for the goods on offer, the greater the customer value. The basic idea is that customers have material needs that lead them to enter into negotiation; the lower the price paid to satisfy these needs, the higher the value that the negotiation will have created for them.

According to this view, the seller value is diametrically opposed as it is associated with economic profit.5 The higher the price that a seller can charge the customer, the greater the value that the sale will generate in terms of profit. Indeed, according to the traditional conception, the seller will always attempt to maximize the profit on a sale.

Are we sure that this vision is complete? Are price and profit the only elements that can create value in trade?

Let us think this over together.

Let’s say that I am one of Renato’s (the sales rep we met at the beginning of the book) prospects and I want to buy a car. Before I make my purchase, I look into the models on the market. I find out which of the cars meet my specifications as regards my travel needs: engine power, spaciousness, fuel consumption, and so on. Once I have decided that a particular model meets my needs, I will want to know if it is reliable, if I can find spare parts and trustworthy service, or if its features will ensure comfortable and safe travel for me and my family. I will probably take into account the information supplied by the media and the reputation of the manufacturer when weighing these elements. The brand image will also enable me to assess the social impact of my purchase, as it will probably confirm or even elevate my status as owner of the vehicle. Once again, I can make these assessments by relying on objective data such as data sheets, test drives, comparative studies, and background knowledge. Will all this suffice for me to make my purchase? Are these the only features I need to consider to meet my needs fully? What am I really looking for when I buy a car? On the basis of past experience of consumption, what really counts and helps to generate value for me after the purchase?

The answer to these questions lies beyond the tangible aspects of a deal and highlights needs of which even the consumer is sometimes unaware, but that are no less important when making the final decision. It will be these intangibles, above all, that will create the customer’s idea of value to which the price is linked.

Let’s go back to my purchase of the car and assume that I have already chosen the brand, model, and optional extras, but I must still decide where to buy the car and with which salesperson I wish to deal. Considering that Joy Motor has a number of car dealers in my area and they are all offering the same price, how will I make this decision?

Any sale involves an exchange between people, and hence a relationship. We don’t all have the same capacity for listening and communication. That slightly magical mechanism that we call empathy6 does not always spark and, above all, is not triggered automatically! Even when we are making a purchase, and perhaps above all, in this case, we want our interlocutor to listen to us, to recognize our needs, and accept them. Indeed, we want to be at the center of our salesperson’s attention, and to feel that our relationship with this person will enable us to gain a greater understanding of the product and provide us with information that will guide us in our choice. The aim of this relationship is to increase our confidence in the decision we are making, which, in turn, can empower us, and perhaps, permit us to dream. This is the extra spark that will convince customers to buy: They need to find out what added value the salesperson, from whom they have chosen to make their purchase, will provide in terms of their relationship.

Customer value can be summed up as follows:

• A proper ratio between the price paid and the material needs

• The ability of the offer to meet intangible needs

• Knowledge and abilities acquired during the exchange

• Opportunity to recognize and share value systems

• Emotive energy derived from the relationship

• Security and pleasantness transmitted by the salesperson

We now come to what value means for the seller. This time, we will play the part of Renato, the salesperson. We want to sell a car and maximize our profits on the sale. Should we try to offer the most expensive model, with the most prestigious accessories, and struggle strenuously to give little or no discount to our customer, while maybe trying to close the deal as quickly as possible so we have time to start a hard sell with another customer?

Before answering this question, let us take a step back and ask ourselves what our goal as sellers is. A good salesperson should first expand his portfolio of customers, and then ensure that these customers remain loyal as long as possible. How do you get these results?

One of the most effective ways to find new customers is that they come of their own accord at the recommendation of friends or acquaintances or due to your reputation. Word-of-mouth recommendations are one of the most powerful weapons in marketing. There is only one way to build customer loyalty and make sure that customers continue to choose your products, and that is satisfaction.

Let us return to the situation we were describing earlier. Thanks to our smooth talking and excellent negotiating skills, we have swiftly managed to convince the customer to buy a top-of-the-line, full option model despite the fact that he came in looking for a small car! Let us now take a look at the consequences of our behavior by asking the following questions:

• Did we listen to the customer in order to understand his real needs and respond with a suitable offer?

• Has the customer concluded the deal poorer or richer beyond purely material terms?

• When he reconsiders the exchange and when using his purchase will this customer return to buy from us again?

• Have we created a situation whereby this customer will recommend our product-service to other potential buyers?

• How did we feel from a human point of view after closing the deal?

These are some of the questions that we will have to analyze in order to understand what added value we have created for ourselves during the negotiation. Here is what goes to make up the seller value:

• Profit generated from a single sale;

• Profit that can be generated from other sales to the same customer;

• Profit that will be generated by referrals from customers;

• The value of customers as referees, that is, we can use their name with other customers;

• Information and knowledge gained through relations with customers; and

• Well-being and professional gratification deriving from creating value for the other person.

We want to dwell a moment on the last point so you can reflect on the fact that salespeople spend most of their professional life with their customers and often much more time than they have for themselves or to spend with family and friends. How much better will your days, and hence your work, be if you create an exchange of energy with your customers that positively stimulates your mood? An exchange that is rewarding at a human level also increases motivation, and as we know, motivation is a key factor to success. As psychologist Shawn Achor brilliantly demonstrated during his presentation at the TED event of May 2011, the equation commitment = success = happiness must be reversed to happiness = commitment = success.7

Finally, yet importantly, remember that the true wealth of salespeople, their life insurance, is their customers. The broader your portfolio of loyal business relationships, the more secure your professional future will be. Is it not worth investing a little more time in your customer than strictly trying to close the deal; especially, if this is an investment in your own future?

We also want to introduce a further consideration regarding value that we will later develop further. While it is true that every actor in the deal—both customer and seller—will still try to maximize their own value, the fact that we have expanded this concept beyond ideas of profit and price allows us to overcome the conflict of interest created by their reciprocal utility functions. When the seller gets a higher profit, the customer cannot get a lower price and vice versa. If we look at the customer value only as the maximization of his purchasing power and that for the seller only to profit maximization then we mistakenly consider the other person as an enemy, whose objectives are in conflict with ours. If your work is imbued with this misapprehension, then your negotiating capacity diminishes and you will fail to create strong relationships, as you are destroying the mutual trust between seller and customer.

Comparing the components that make up customer value with those of the seller, you will discover that many of them correspond or are functional to each other.

For instance, if our customers consider it valuable to have a single interlocutor who will follow them as a guide (because this makes them feel more secure), we as sellers equally seek lasting relationships with customers who appreciate our professionalism as we find this gratifying! This process of overlap between our idea of value and that of the customer is very similar to what John Dovidio and Samuel Gaertner called “activation of a common identity”8 and that we could summarize in the ability to find and highlight the things we have in common with our customers. We must not forget that among the components that combine to generate value, there is also the act of negotiation itself, which is a source of satisfaction and personal gratification.9 You could almost say that you pocket part of your reward in advance!

Besides, thinking only in terms of profit not only generates a conflict of interest with the customer, but can also trigger an identity conflict in the seller. If while negotiating we forget that we also have to nurture our need for relationships, our personal values, and our need for gratification, sooner or later internal boycotting mechanisms will be triggered. In fact, if the goal that we have set for the sale is not in keeping with our inner principles, we unwittingly adopt behaviors that result in failure to sell; thus confirming to ourselves the validity of our principles, which a sale would instead invalidate.

This is what happens to those salespeople who, with undisguised satisfaction, justify themselves to their boss for their failures with phrases like “I told you it wouldn’t work” or “Of course I haven’t sold it, the product’s unsellable at that price.” If the conflict of interest destroys mutual trust, an identity conflict destroys self-confidence and motivation, which is precisely why it is so dangerous! (See Figure 2.3.)

Figure 2.3 Conflicts of interest and identity conflicts

The first objective in Sales Ethics is therefore to investigate and identify in detail the components that comprise value for us and for the potential customer, find any points of contact and then work—in the most efficient manner possible—to increase both. In this way, we will act according to a logic of maximization that is in line with the rules of the market and does not generate conflict between the actors involved but rather helps to reduce them.10

Sales

It may seem strange that one of the concepts that needs to be clarified is sales, but we believe that the meaning of this term cannot be taken for granted even though this book is primarily addressed to experts.

In our view, a sale is an exchange that aims to create value for both parties involved. Hence, to define the meaning of the word sale we need to explain what we mean by value and, as we saw in the previous section, this goes beyond the simple idea of a profit for the company and the right price, or a lower price, for the buyer. But another myth that needs to be debunked is that the sale and the capitalization of its value or the proceeds that it generates are precisely defined moments in time and space. In an increasingly complex and dynamic market, the moment when the contract is closed rarely coincides with the stage when maximum value is generated. In fact, often the proceeds will be collected over a period of time and the degree to which our behavior is ethical during the negotiations will significantly affect the success of this delicate operation. Complaints and objections have a cost (in terms of effort, time, and money) that can significantly affect the profitability of our commercial action. To explain this concept, let’s go back to our car salesman. From his point of view, his sale was perfect: he kept the price high, he convinced his client to purchase the most expensive product in the catalog, and he made the negotiations brief. Let us, however, ask a few questions:

• What happens when the time comes for the buyer to pay the first installment on the car?

• How will the buyer behave in dealings with the after-sales service if a technical problem crops up or when the car needs servicing?

• What assumptions will the buyer now have in any business interactions with the same salesperson and car dealer?

If we think of sales as a process that unfolds over space and time, and not just an event that begins and ends in a single moment and in a single place, we will realize that it is natural to ask these and other similar questions at an earlier stage. In fact, the generation of material value to the seller does not end with the signing of the purchase agreement but continues over time. If, in addition, we consider the intangible aspects of value, we know that some of these are generated before the sale. In the following, we illustrate three stages of the sale and the elements each of them can contribute to creating value for sellers:

Presale

Getting to know the customer

Information on the market

Generation of revenue

Personal gratification

Achieving budget

Postsale

Generating referrals

Positive word of mouth

Collecting proceeds

Ease in handling complaints

Further purchases

If we forget that our relationship with the customer does not end at the exact moment of the sale (especially when we are selling complex goods or services), we will generate costs that we will be forced to repay directly or indirectly. It also means losing out on potential future profit that might result from further purchases by the same customer or from new customer referrals. If we consider the sale as an ongoing process, we will manage the relationship with greater foresight, accepting that sometimes the customer cannot buy (or cannot buy from us) without compromising this relationship. Many companies have realized that the after-sales service is not only the most profitable part of the business, but also the most risky in terms of cost control. If the relationship has set off on the wrong foot, due to a poorly managed sale for example, then what should have been a profitable opportunity would turn out to be the opposite.

Considering the sale in this broader perspective, it is also evident that each sale involves a larger number of actors11 as the company departments connected to customer management (administration and after-sales service to name just two) contribute to the generation of value. The role of a salesperson should involve guiding and coordinating these various functions; this is why we must improve our ability to interact with others and work effectively as part of a group.

You may ask “What about sales on the Internet where payment is made immediately by credit card, is the sale still a process or just a single event?”

Once again, we consider it a process, for two reasons: reputation and relational costs.

In markets that are vast (and Internet is one of these) where buyer- seller interactions are much more numerous and therefore apparently less controlled, there are compensatory mechanisms that ensure that opportunistic behavior that damage customers will lead to costs in terms of a worsening relationship or diminished reputation. Although this type of cost may not be immediately evident, in the medium to long term it may lead to the ousting of the seller from the market.

Let’s push this to the limit by imagining that Renato starts up an Internet site to sell cars online and demands advance payment by credit card. He then manages to move his first car, but sells a product that does not live up to his description. At this point, he’s not in the least concerned—he feels protected by the physical distance between himself and the buyer. Moreover, he has already pocketed the money and he thinks he has got away with making a handsome profit on this sale (we use the word profit and not value because, as we know, the latter has a much broader meaning). Yet the negative feedback from the customer he cheated will soon spread and eventually Renato’s bad reputation will catch up with him, and he will be forced out of the market and made to repay the entire cost of his wrongdoing.

Externalities and Information Asymmetries

When consumer demand linked to needs coincides with supply in terms of products and services, the market is in equilibrium and the price is determined (see Figure 2.4). At least this is what basic economic theory states. In reality, however, there are many forces influencing the encounter between sellers (supply) and customers (demand). These forces not only allow the price to fluctuate in a more complex way than the simple supply–demand ratio would explain, but also can derail a deal even though our product is perfect for the client. Alternatively, a deal may sometimes go through even when this would not seem possible, when my product is more expensive, for example. We are talking about externalities and information asymmetries. These are forces that interfere with the dynamics of the market, and they are so powerful that they are considered strategic elements that must be taken into serious consideration during a business negotiation.

Figure 2.4 Market equilibrium

The term externality refers to the effect that, whether beneficial or not, our actions on the market may determine the well-being of a third party without them immediately paying a price or receiving a payment resulting from our action. The existence of externalities mean that the price reached within a single sale may fail to reflect the costs or benefits engendered. If, for example, I buy a car that creates a lot of pollution, I will thereby create a disadvantage for the community (due to pollution), but I will not have to pay for this disadvantage directly at the time of purchase. Temporarily, the social cost remains unpaid, but it will affect the long-term dynamics of the market and will thus affect the balance. For instance, there may come a time when the social costs of the negative externality pollution will be so high that some citizens will be forced to stop using their cars to avoid accusations of damaging the ecosystem.

If you are particularly careful about the relationship you have with the customer during a negotiation, you will not immediately receive a higher payment, but you do generate positive externalities that in the medium to long term will create a benefit in the form of word-of-mouth recommendations and an improved reputation. The decision to invest in building a positive image is thus an effective strategy that will improve your chances when bargaining. A negative reputation, on the other hand, creates costs that might seriously compromise your future sales. If we consider once again the example of the online car sales hypothesized in the previous section, we can see that by acting unethically the seller generates negative externalities that create relational costs that will have to be repaid.

Information asymmetries are differences in the knowledge the seller and customer possess regarding the object of their negotiation. In many cases, sellers may exploit the difference in the information level to their own advantage, but frequently they themselves are victims of this asymmetry. We can illustrate this with an example: Renato knows that the model of car he is proposing is plagued with technical problems, whereas the customer is unaware of this; hence the power relation between the two shifts. The extra information Renato possesses permits him to maintain the price artificially high despite the unreliability of the product. It is clear that the natural balance of the exchange is upset by the fact that the two actors do not have the same level of information. This is an example of a case where sellers may take advantage of an asymmetry of information to their own advantage.

Now imagine instead that Renato’s company has launched a new vehicle, based on a technology that is so innovative that the majority of customers know nothing about it. The potential buyer is not equipped to evaluate the characteristics of the new car, because they are so different and cutting-edge that a comparison with rival manufacturers is impossible. If customers cannot understand the benefits to be reaped from this new technology, on what basis will they decide whether or not to buy the car?

When we make a choice, but are not in possession of all the elements necessary to make an evaluation, we fall back on an analysis of assessments used in our previous consumption experiences. In the case described previously, as in most cases and in the absence of other more specific information, we will attempt to understand the value by considering the price.12

Renato’s customer might be inclined to think that the above-average cost of the car indicates higher quality, because—in the absence of other elements that permit a more accurate assessment—his experience of consumer products leads him to expect the most expensive products to be the best. On the other hand, being unable to appreciate the special characteristics and the actual value, the customer may judge the price too high, considering it a car much like any other. The only alternative for the salesperson in this case will be to offer discount, as the only bargaining tool that remains is the price.

Thus in the second scenario Renato is the one to lose out because of the information asymmetry that he was unable to manage. By failing to provide adequate information, he did not enable his customer to understand fully the value of the offer and was forced to fall back on discount to conclude a sale. In addition, commercial exchanges based on price alone are destined to be fragile: A rival need only lower the price by one cent to convince our potential customer to buy elsewhere.

Marketing experts are well aware of the tendency to associate price alone with value, and often exploit this by withholding information from the customer or creating a situation where comparisons are unlikely, and thus inducing the customer to believe that because a product is more expensive it is undoubtedly better. This strategy, however, destroys consumers’ trust, as after buying the product, they will be able to better evaluate it and gauge if they have been have tricked. If we exploit a lack of information to gain an unfair advantage, the customer is more likely to be disappointed with the purchase. This in turn will lead to loss of customer loyalty and negative word of mouth.

If we destroy trust, as the current recession demonstrates, the market will shrink and there will be less opportunity to make sales and fiercer competition for the remaining customers. If we provide customers with new information thereby enhancing their decision-making power during the bargaining phase, we will generate value for them and for ourselves by increasing the total energy of the system. This new energy will fuel the market, keeping it buoyant and active for future trade.

If we ignore the fact that all our actions will influence future events (creating externalities and relational costs), or, even worse, if we reduce the customers’ power of choice by using the extra information we possess to put them at a disadvantage, in the medium to long term, these actions will erode our ability to generate value. In Chapter 5, we will learn how to solve information asymmetries and utilize positive externalities over time to negotiate in an ethical manner. By improving our reputation and trust, we will trigger virtuous mechanisms that will allow us to prolong the relationship over time and encourage new deals. We will provide the customer with all the truly empowering information required,13 so that the negotiation becomes an opportunity to learn and acquire knowledge, which in turn will lead to opportunities beyond this single sale.

Reciprocity and Cooperation

As we said earlier, a sale is a relationship with a purpose. The concept of relationship is based on two terms that are only apparently similar: cooperation and reciprocity.

Cooperation14 means working together to achieve a goal. In commercial language, we generally associate the idea of cooperation with a nonprofit organization whose objectives are social, that is, linked to the welfare of a group of members and not to an individual. When we use the word co-operate in the context of Sales Ethics we mean acting together to achieve a goal. This does not necessarily imply that the goal is the same for both actors, nor that the cooperative action is purely altruistic or social and unconnected to the logic of maximization of individual advantage. Indeed, we will see how cooperation, considered in these terms, may be the best strategy to achieve your individual goal more efficiently.

Since it includes the active involvement of the other party, this strategy can only be pursued by respecting certain requirements that may seem to be a compromise but which, on closer inspection, do not affect our advantage. For example, if I want to convince my neighbors to help me mow my lawn, I’ll probably offer to give them a hand another time. We are both considering our own interests (mowing our own lawns), but for maximum efficiency, we decide to cooperate. On the other hand, if we each decided to work alone, our efficiency in pursuing our own goal would be compromised (we would be slower and have to work harder) and we would lose the relationship benefit derived from establishing a useful connection for undertaking future work as well as the pleasure of spending time together. Some might argue that cooperative strategies are applicable only when the objectives of the actors involved are not in obvious contrast, which is the case in a sale where an increase in the seller’s profit corresponds to a disadvantage in terms of price for the buyer and vice versa. As mentioned earlier, many of the apparent differences between the goals of the customer and the seller disappear (or greatly diminish) on a closer analysis of the conflict of interest. We will provide a further demonstration of this when we discuss the theory of repeated strategic games. For example, if we extend the arc of the business relationship beyond the moment of the single sale or replace the concept of profit with that of value, we find that, in fact, not only are most of the objectives that the salesperson and the customer pursue not in conflict, but also, in many cases, they coincide and support each other.

Reciprocity differs from cooperation as it refers to the bond created between the actors in an exchange: If I give something, I expect something in return; if I receive something I expect that sooner or later, either directly or indirectly, I will have to give something back.

Reciprocity is a well-known concept in economics: The simple precept according to which we must give before receiving15 is at the basis of the idea that investment (and related costs) precedes revenues. Yet, if we think of reciprocity as a regulator of material exchanges alone, the mechanism might not appear infallible: There are many occasions when someone receives (or takes) something without giving anything back; vice versa, we may give selflessly without receiving anything in return. In the light of these experiences, the concept of reciprocity would seem applicable only to certain categories of exchange and not to others. Such reasoning, however, ignores a truth that is as important as it is simple: Every exchange between people (including sale) comprises both tangible and intangible components, including relational elements, and its consequences may appear over an extended period, not only at a specific moment. If we consider the relational and time dimension when considering the mechanism of reciprocity, its ability to regulate the balance within an exchange is greatly enhanced.

Take the case of sellers who take more than they give. From a purely material standpoint, it would seem that no mechanism intervenes to balance the exchange, but from a relational perspective sooner or later they will have to pay a price for their misconduct. This price will take the shape of a rupture in the relationship with that customer, or worse, a bad reference that will damage the seller’s image. Yet what happens when a salesperson gives more without receiving an immediate benefit, or when someone actually gives something without expecting anything in return? What regulatory mechanism is involved this time?

As demonstrated by numerous case studies collected by Adam Grant, whose theories we will discuss in the next chapter, the salesperson who gives more today triggers a mechanism that strengthens the relationship with the customer who feels committed to pay back the surplus received in a more or less direct way. Moreover, the salesperson will find personal satisfaction in offering the customer an unexpected benefit, a gratification that will boost self-value and increase motivation in subsequent dealings. Reciprocity can take place on different levels,16 and at its extreme, it generates a balancing mechanism based exclusively on self-gratification: If I give, what I get in return is only the pleasure of a kind and altruistic act. This pleasure alone balances and in a sense repays my action.

We will use the two concepts of reciprocity and cooperation throughout all the stages of Sales Ethics, learning to optimize results and make processes efficient through a precise collaborative strategy with our customer. We will invest in relationships to trigger mechanisms of virtuous reciprocity that will open up new market opportunities and increase value creation.

Well-being and Well-having

Just as there is a distinct difference between having and being, there is also a difference between the idea of well-being tied to material possessions and that linked in turn to the quality of our inner life. People have been debating the relationship between wealth and happiness for years. Numerous international studies have shown that an increase in material richness does not have an immediate effect on happiness, in fact in certain ways and under some circumstances, these two concepts are inversely related: Beyond a certain limit of accumulated assets, happiness may decrease due to increased responsibilities, the complexity of management, and the anxiety level related to possession. For this reason, some governments in order to define their country’s level of well-being have proposed a more sophisticated measurement of gross national happiness (GNH) to supplement the measurement of gross domestic product (GDP). If adopted, this indicator would certainly make it even more obvious that there is a more complex relationship between wealth and happiness than that normally attributed to them, suggesting that we should not consider these two concepts to be directly proportional. Research like that of Shawn Achor, whom we mentioned earlier, some of which was carried out on behalf of the UN, has demonstrated how happiness affects productivity (thus GDP) and not vice versa. This would indicate that our inner world may influence the world outside us and that well-being generates well-having. If we look at the Italian situation in particular, this becomes even clearer. Unethical behavior, which can adversely affect professional relationships, generates levels of unhappiness, which seem to have affected the creativity and capacity for innovation that previously characterized our country and which enabled us to emerge from previous crises.

We will thus replace the concept of well-having (linked to the possession of material things) with the concept of well-being (linked to the quality of our life), which includes a number of elements that are not always easy to measure.

Returning to the concepts of customer value and seller value, we said that they not only comprise the material aspects of profit or fair price. Value is, in our view, linked to the idea of well-being—we could even say that high levels of well-being correspond to highly generated and accumulated value. Each of us belongs to a different social and cultural group, with diverse backgrounds, identities, and personal experiences: All of the elements combine to form our personal conception of the quality of life. If we consciously understand our own idea of well-being, we are on the way to achieving it. Moreover, the process we choose to achieve well-being generates investment costs of a tangible and intangible nature.17 We will not get results unless we aim at the right target, just as a mistaken investment will not produce revenue.

How can we be effective in achieving a goal if we are not fully aware of what we are targeting? If we have little or no conscious idea of what quality of life means for us, we cannot pursue it efficiently, and we might overlook the costs it will entail. Yet the fact that we do not expect certain costs does not exempt us from having to pay them. This situation may leave us bewildered and create a sense of unease or alienation from our own goals that we are frequently unable to explain.

To clarify this concept, we will give an example from a real case (we have replaced the names for obvious reasons). Each year Mr. Rossi spends his holidays on a boat in a fashionable tourist resort frequented by the jet set. Although the canny Mr. Rossi could well afford a berth in the luxurious yacht club and enjoy all the amenities provided for tourists, he chooses to moor away from the quay to avoid paying the fee. He ties his boat to a private pier belonging to a villa that, as he discovered a few years before, is empty in August. With the collusion of the guardian, to whom Mr. Rossi gives a handsome tip, he can stay there for the whole month, provided he keeps the lights off (to avoid alerting the neighbors) and leaves the jetty every morning when the sun comes up. Obviously, he cannot fill up with water, use the mains to recharge the yacht’s batteries or use the services on land that would be available at the yacht club. But Mr. Rossi has managed to find a way to get into the club with his wife, take a shower and fill his bins with water, thanks this time to a little help from the staff (who once again get a tip). He and his wife are therefore delighted to enjoy their five-star vacation while apparently spending very little, though they do have the inconvenience of setting off early each morning, traipsing two miles on foot from the mooring to the club to have a shower, and the anxiety of being discovered.

If we look at Mr. Rossi’s strategy purely from a material point of view, he is in fact, maximizing his purchase of a summer holiday in a luxury resort. There is no doubt that he spends at least 10 times less than an owner who has booked a regular berth. It is also true that while Mr. and Mrs. Rossi do not have the same comforts as the others, they are still moored in a safe place and, with a little effort, can enjoy a number of basic services. Is it therefore true to say that the couple are maximizing their value overall?

To answer this question we need to ask Mr. and Mrs. Rossi some questions:

• What is their main reason for going on vacation?

• Why, of all the possible places, do they choose to take their holidays in a luxury resort and what do they expect from their time there?

Let’s assume they choose to go on vacation primarily to rest after a year’s work, and they are particularly fond of this particular resort because:

• The hospitality services are among the best.

• Their image and reputation will be associated with that of an exclusive resort.

• They want to mix with famous people and improve their network of contacts.

It is immediately obvious that their main reasons for choosing a five-star resort for their vacation are more intangible than tangible given that these reasons are linked to concepts such as relaxation, hospitality, image, reputation, and exclusivity.

Based on such considerations, it is clear that an assessment of the value generated by Mr. and Mrs. Rossi that considers only material elements (as they seem to do themselves by focusing on cutting costs) is a blunder.

Some might argue that the couple’s idea of a vacation is fulfilled by their choice of behavior, and that if they were to spend more money (paying for the berth in the club) this would add little or nothing to the quality of their stay and might even diminish their pleasure, as they could no longer experience the thrill some people get from saving money.

To reply to this objection we have to go back to the concept of intangible relation-based costs that we mentioned earlier. Mr. and Mrs. Rossi (even if they do not know it or are unwilling to admit it) are in fact incurring costs that they eventually will have to repay. Let’s make a list of the main ones:

• Their vacation, with its early-morning starts, two-mile treks for essentials, and the anxiety of being stowaways will be anything but relaxing.

• The image that they hope to create by being seen at exclusive resorts and prestigious clubs continually risks being destroyed by a simple accident.

• The luxury and superior level of service that Mr. and Mrs. Rossi aspire to remains out of reach, just beyond a fence that they only rarely dare to climb over, and at personal risk.

If we add up all these hidden costs that the Rossi couple are already paying or will pay eventually, can we still be so sure that they are maximizing value for themselves?

If they were to reflect on their idea of value, going beyond the material aspects, this crafty couple might as well choose to behave differently by deciding, for example, to anticipate some of the material costs to fully enjoy a true five-star vacation, but to, above all, avoid paying the far more onerous intangible costs at a later date.

If we were to consider the production of well-being like an industrial activity and draw up a budget for it, we would divide the costs in the income statement into two components, tangible and intangible ones, including relational costs in the latter. The same two components would appear under the heading of revenues with a list of everything that generate tangible and intangible value.

The difference between costs and revenues, thus identified, would determine the profit or loss that contributes to increasing or decreasing our overall capital of well-being.

Revenues [tangible and intangible] − Costs [tangible and intangible] = Profit or loss of well-being

The Circle of Trust

Many of the barriers that stand between us and the achievement of our success (which is linked to our well-being) are connected to trust: in ourselves, in others, and that of others toward us.

When we transfer this concept to sales, we need to analyze how to build and maintain trust in the salesperson–client relationship, because the success of our negotiations will depend on this.

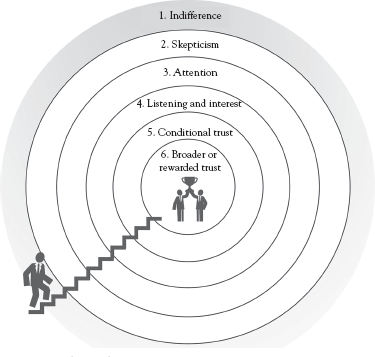

We can imagine trust as a system of concentric circles with the customer at the center (see Figure 2.5). The closer we get to the center, the stronger the bond of trust and therefore the stronger the relationship. The goal of any good salesperson is therefore to climb consciously all levels of the circle of trust until reaching the core. As you will see, the outer levels of the circle of trust correspond to indifference and skepticism, indicating our customer’s initial unwillingness to meet with us. This is because customers are victims of the apparent conflict of interest associated with the sale, convinced that our only objective is to maximize our profit, while they will be intent on maximizing their purchasing power, and they believe the two things are irreconcilable.

Figure 2.5 The circle of trust

The six levels of the circle of trust are explained as follows:

1. Indifference: At this level, your customers have not noticed you or if they have, they have not yet decided to focus their attention on what you offer.

2. Skepticism: This is the moment when customers are aware of your existence and are watching you from a distance, trying to collect information in an indirect way. In this phase, customers form a first impression that could be very difficult to change.

3. Attention: Customers are focusing their attention on you. Something has caught their attention but they have still not decided whether you can be trusted. From this point onwards, you will be closely observed, but you have started to break down their skepticism.

4. Listening and interest: The relationship with customers is now direct. They ask questions and you must answer requests. Your interlocutor is trying to connect with you to build up trust.

5. Conditional trust: This usually coincides with the first sale that may often be considered a sort of “test” by customers. They are thinking, “Alright, this time I will trust you, let’s see how you behave from now on.” At this stage, you have to commit to repaying the customers’ trust, by assuring a return on their investment in you.

6. Broader or rewarded trust: The relationship is robust. Your customer has formed a positive opinion of you and is willing to trade with you again. This level creates positive inertia that will allow you to overcome small conflicts that you must, however, always strive to recognize, understand, and address, taking nothing for granted. At this stage, a virtuous cycle is triggered in the relationship that can generate well-being for both of you and may spread to include new people: The customer creates value for himself and for you, by self-generating motivations and arguments for purchase and providing referrals for you with new customers.

It is important to emphasize that trust is a dynamic force, so you need to invest energy and attention to protect and maintain it over time. Each level has specific problems and as you get closer to the center, it is important to remember to maintain the trust nurtured in the previous stages.

The migration from the first to the third level is affected by indirect activities, such as reputation, word of mouth, positive references, and marketing in general. From Level 4 onwards every stage depends directly on the salesperson who must pass an actual test of trust based on each sale, especially the first. The highest level of trust leads to the creation of forces capable of generating new interactions and value in a spontaneous way: Customers who have greater trust will be happier to buy from you again and to introduce new customers to you. Here the role of the salesperson is like that of an orchestra conductor, who guides the customer who then interacts independently with other areas of the company.

As we will see when discussing bargaining techniques, the six levels of the circle of trust correspond to different stages in our progress in Sales Ethics and every technique described will be used to move up to a further level of trust.

Remember that if you wish to establish a sincere and long-lasting relationship with the customer you must first resolve your personal identity conflicts—then you will be ready to tackle the conflicts of interest arising when you deal with the customer. Sellers who have failed to resolve their own conflicts of identity, in fact, will lack self-confidence and will find it difficult—if not impossible—to find valid arguments when bargaining as they will unconsciously boycott their own efforts in their relationship with the customer.

Finally, we want you to note that reciprocity is a powerful tool when establishing and building trust. In fact, as demonstrated by Pelligra18 in the Trust Game (Gioco della Fiducia) and McGregor19 with the theory X and Y, if we trust someone they will reciprocate. This is why the rings in the circle of trust not only describe the customers’ approach to salespeople, but also describe the way that salespeople consider their customers. At the level we described as skepticism, for example, both the salesperson and the customer will share a tendency to be influenced by first impressions. If we want to remove our customer’s prejudice, we must be the first to maintain an open mind and avoid falling into the trap of hasty judgments or bias based on previous experiences.

The law of reciprocity, summed up in the motto that you must first give to receive, is further confirmed as we move up the levels of circle of trust; this law serves to identify the most powerful tool you have for progress: Be the first to offer trust and focus your attention on your customer!

• What does your offer system include? What, how, and why do you sell? Observe the diagram of your offer system and write down everything that, in your opinion, the customer buys from you. Include both tangible and intangible aspects in your list. Try to be very specific and remember to include yourself, describing the things about you that the customer chooses to buy. Lastly, ask yourself if you remembered to argue and specify every element of your offer system.

• What contributes to generating value for you (apart from profit) when negotiating? Divide a piece of paper into two columns with a line down the middle. Write Profit at the top of the left-hand column, then below that write down what you expect from a sales negotiation. Write anything that comes to your mind, such as information about the competition, your desire for recognition in your professional role, or your gratification when assisting your customers … .

• What can be considered value for your customer (apart from getting the best price)? Write Best Price at the top of the right-hand column and then list below the things that, in your opinion, your customers want for themselves from the bargaining. Avoid generalizations such as quality or trust, but specify exactly what these terms may mean to a customer.

• What do your concept of value and that of a customer have in common? Compare the two lists: What do they have in common? Draw a circle around the points that match or are similar with one in another column and join them up.

1 Research by the Corporate Executive Board, the results of which are presented in the book The Challenger Sale by M. Dixon and B. Adamson (2011), highlighted the contribution to customer loyalty of the various components of the offer system: 19 percent brand, 19 percent products and service delivery, 9 percent value-to-price ratio, and 53 percent buying experience. The research is the result of studies made on many companies from different business sectors.

2 Quoted in Quinones (2010).

3 We will further discuss information asymmetries shortly, and explain how their presence causes customers to focus predominantly on the price when judging the quality of what we are presenting. Information asymmetries are an essential element in the link between price and perceived value.

4 More precisely, economic theory defines the objective that the customers seek to maximize when they negotiate price as the utility function.

5 In line with the definition given in the preceding footnote, the maximization of profit is the seller’s utility function.

6 Empathy is the ability to understand fully the state of mind of others without necessarily sharing it.

7 TED is an international nonprofit organization that holds conferences around the world on various topics from the economy to the environment, with the aim of increasing global knowledge and sharing ideas. For more information visit www.ted.com

8 Dovidio and Gaertner (2000).

9 Scientific research has shown that whenever we give or receive trust, our hypothalamus produces oxytocin, an antistress hormone that allows us to enhance our enjoyment of human relationships.

10 Game theorists define integrative bargaining as negotiations that can produce a win-win situation, by contrast with distributive bargaining in which one side wins what the other loses. The former are also called nonzero-sum games and the latter zero-sum games. Thinking about value for the seller and for the customer, rather than focusing on price and profit, means moving from a system of I win and you lose to one where we can both win.

11 We will consider this in detail in Chapter 4 when discussing internal clients.

12 This is why negotiations often center solely on price. In fact, when customers have not received all the information necessary to evaluate a product, they refer to the price when reaching a decision. In our training sessions, we frequently encounter salespeople who complain saying, “Customers are only interested in the price.” This may happen because they have not been provided with other elements that permit them to evaluate the offer system.

13 To achieve maximum effectiveness in the negotiation of the sale, we will learn to select what information we must provide to empower customers in their choice without confusing them and to reinforce their confidence in the exchange.

14 In game theory, the term cooperation refers to a common purpose within a group sanctioned by rules and agreements. The term cooperation is used here in a more conversational way, meaning a collaborative approach adopted by agents in order to achieve their goals more effectively.

15 Common sense should remind us that in nature, the harvest takes place after sowing and not before. The mechanism of reciprocity confirms that it is natural to first give something to our customers and then collect our reward.

16 Certain authors talk of different levels of reciprocity. See Bruni and Pelligra (2002).

17 We can define intangible costs as those costs that are repaid through intangible assets such as reputation and image: Relational costs fall into the category of intangible costs.

18 Pelligra (2007).

19 McGregor (2006).