A lot has been discussed about the limitations of an adaptive learning organization and a generative one. We live in a world of rapid changes, economic and technological, as well as cultural and political. In order to remain competitive, organizations must be able to transform, both to adapt to the changed business environment, as well as to proactively ready themselves for the next wave of changes to come.

Transformation, in turn, requires excellence in strategy, organization, and systems. When all these three components are effectively considered, not only can the implementation risks associated with any transformation within an organization be reduced, but also success can readily be achieved. After all, the goal of knowledge workers and knowledge managers is to ensure every individual in the organization is ready for transformations at any given time.

The ultimate goal of KM is to enable the development of collaborative enterprise systems that allow every individual inside the organization to become a learner, as according to Hoffman,1 “learners, in a world of change, inherit the world, [while] learned remains beautifully equipped to deal with a world that does not exist.” Knowledge workers can tremendously increase an organization’s effectiveness through common knowledge practices. Knowledge is the key differentiator in today’s business, and the one responsible for all the business transformation that is taking place. So, you either lead it or follow.

Now, capitalizing on knowledge is actually not as complex as managing it. When it comes to running a business successfully, the greatest CEOs rely on common sense, not complex mathematical formulas. As Ram Charan2 describes, it is necessary business acumen. I believe, as part of this business acumen, knowledge workers should help CEOs and the executive staff to also understand how to build enterprise systems, to deal with the peril, promises, and the future. After all, information must be managed.

Organizing Knowledge and Know-How Through Business Thinking Practices

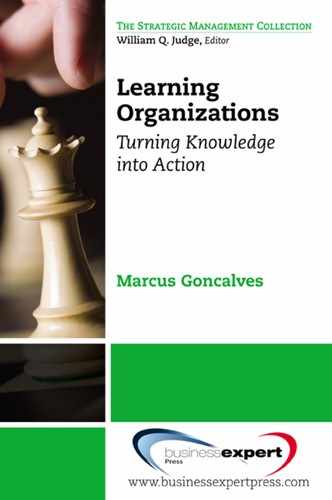

Organizing knowledge and know-how requires interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary skills. Having a great focused knowledge on a particular segment of the company or industry will not suffice. On the contrary, it will create barriers to full understanding of business and common sense across the organization. That’s why I keep emphasizing the role of knowledge workers in developing business thinking practices that not only the executive staff can tap in to, but also the whole organization. Any learning organization must understand the total business cycle every business abides by in order to be able to measure quantifiable business results, as depicted in Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1. Understanding the main elements of a total business cycle is important in developing business thinking practices.

As we learn to view a learning organization as a whole, not broken into departments, functions, or tasks, it will begin to function in a more fluid way. Meetings will be less bureaucratic and more goals oriented. The organization will also be more transparent between distinct groups and the total business cycles phases.

At the Core of Every Business Thinking Practice

At the core of every business thinking practice you will find the same: the goal is to make a profit. To make money a business needs to generate cash, and add that to return on assets (ROA) and to growth. Now, how do you get the whole organization to think that way? By being their best coach.

The difference between an organization and a football team is that the organization has to deal with very tangible milestones (well, the team must score!) and needs to produce quarterly reports. In both instances, to be successful, you still have to develop a knowledge strategy, one that organizes knowledge and know-how, and then enables it to be shared throughout the organization and among its business partners.

To seek competitive advantage you must be convinced that the organization’s knowledge needs to be organized and managed more effectively, being readily available to be exploited in the marketplace. Knowledge and know-how, as well as other forms of intellectual capital, are your company’s hidden assets. Although they are not visible in quarterly reports and annual report balance sheets, they underline the creation of value and future earnings potential. That is why knowledge intensive companies such as Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Roche, and Glaxo Wellcome have market values at least 10 times the value of their physical assets.

Thinking Practices Generating Knowledge Advantage

One of the main thinking practices in KM is to realize how organizations can use knowledge to secure a strategic advantage. Basically, it is by generating greater value through the knowledge, thus acquiring know-how in products, people and processes, for instance:

•People’s Know-how: Anglian Water, one of the leading providers of water and wastewater services in the United Kingdom, has been investing in learning organization programs as one way of nurturing and applying underutilized talent within the company.

•Processes’ Know-how: Texas Instruments realized that it was typical to often find differences in performance levels of 3:1 or more among different groups performing the same process. They decided to invest in KM applied to their processes to close the knowledge gap, which saved the company the cost of one new semiconductor fabrication plant, or $1 billion in investments, if you prefer.

•Products’ Know-how: Petrobras, the Brazilian petroleum company, one of the largest in the world, realized that intelligent products could promote premium prices and be more beneficial to users, so they invested in an intelligent oil drilling system that bends, and weaved its way to extract more oil than ever from the pockets of oil under oceanic ground formations.

Such examples of strategic advantage developed through KM are only one way that investing in knowledge pays off. Another is through active management of intellectual property (IP) portfolio of patents and licenses, as well as organizing knowledge so you can exploit it internally by generating information and know-how.

Promoting Team Work as Knowledge Transfer Tool

If we take the example of a cardiac surgery team, we find this is a team that must work very closely together. In an operating room, a patient is rendered functionally dead while a knowledgeable surgical team conducts the surgery. The amount of synchronized knowledge transfer, in real time, and teamwork that goes on is just astonishing. Any mistakes can be disastrous.

The most interesting thing is that such teams are not that different from your executive staff or any other cross-functional team so crucial to business success. Learning organizations can learn a lot from such high-risk surgical teams, in particular with regard to executing existing processes efficiently, and most important, by implementing new processes as quickly as possible.

In the process of becoming an effective learning organization you will have to adopt new technologies and very likely new business processes, which is a highly disruptive task. In addition, you will have to focus on how your organization’s teams learn and why some learn faster than others. To be successful, organizations must capitalize on leaders that actively manage their group’s learning efforts. And when implementing new technologies and processes, make sure these innovations are directly targeted at learning; every individual in the team is highly motivated to learn and upper management is fostering an environment of psychological safety through effective communication and innovation.

Of course, to convince traditional organizations that teams learn more efficiently if they are explicitly managed for learning poses a challenge in many areas of business. One of the main challenges is that the majority of team leaders are chosen not for their management skills, but for their technical expertise. Thus, to be successful, organizations must invest in team leaders that are adept at creating learning environments. Upper management must be able to look beyond technical competencies and work with leaders who can motivate and manage teams of disparate specialists.

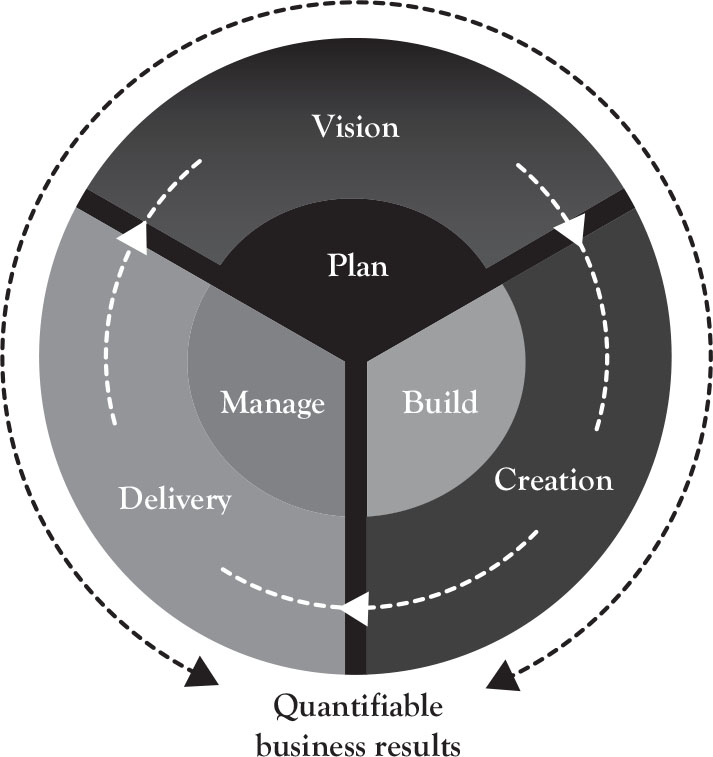

Using teamwork as a knowledge transfer tool enables you to tap into not only the explicit knowledge of team members, but also tacit ones. The goal should be adopt a new sense-and-respond business model that can help the organization anticipate, adapt and respond to continually changing business needs. Team members should be able to identify the three main stages of learning and strive to close the circle of learning, as depicted in Figure 5.2. Stages of learning: by identifying, striving and closing the learning stages circle members of a learning organization can be better equipped to sense-and-respond to new business needs.

Figure 5.2. Stages of learning: by identifying, striving, and closing the learning stages circle members of a learning organization can be better equipped to sense-and-respond to new business needs.

In order for teamwork to be effective, it must be able to generate and share new knowledge. As Figure 5.2 shows, there are three learning stages any individual or team must go through to successfully learn, deploy, and share new acquired knowledge.

The first stage, the acquisition of information, raw materials of learning is gathered. It is very important for those in this stage to know what they want to know, from where, and for what purpose. Otherwise, not only will they end up with an information overflow, but they will also know a lot of irrelevant stuff—useless knowledge. As discussed in chapter one, Sir Francis Bacon’s premise that knowledge is power no longer holds true if knowledge is not followed by action, a successful and purposeful one.

The second stage, the interpretation of information, requires the development of perspectives, positions, opinions, and elaborated understanding. At this level, materials collected in the first stage are analyzed and reviewed. Here, you must make sure that there is an understanding about what that information means, and the cause-and-effect of the relationships it produces once applied.

The last stage, the application of information, is when organizations finally decide to engage in tasks, activities, and very important, new behavior. It is here that analyses are translated into action. It is here that the organization must ask itself what new activities are appropriate or necessary. What behaviors must be modified? David Garvin wrote extensively about the process of turning learning into action in his book Learning in Action,3 which I strongly recommend if you really want to put your learning organization to work. Another excellent book, and more recent, is Know Can Do!: How to Put Learning Into Action, by Blanchard, Meyer, and Ruhe, published by Macmillan in 2007.

Adapting to Unpredictable Demands

Organizations will be able to adapt in a systematic way to the unpredictable demands of rapid and relentless changes if they are designed and managed as an adaptive system. However, even though adaptive strategies are very important in the face of change, the ultimate goal of any learning organization is to be able to predict the changes before they occur and position themselves proactively, instead of reactively. The questions knowledge managers and executive staff should be asking at all times is: first, how can they integrate the organization, as a whole, to achieve its business purposes; and second, how can they cope with the rate of changes inside and outside the organization, and still be able to create an organization’s “central brain” that keeps the rate of change of the organization equal to or greater than the rate of environmental chance.

Bill Gates, in his now old (yet current!) but still legendary book Business @ the Speed of Thought,4 alluded to the importance of an organization’s digital nervous system. Enterprise systems can enormously help organizations to think rationally about developing this much needed digital nervous system, as it presents a new model of corporate computing. Although knowledge workers may not have the power of implementing such systems, which legally comes from above, from the Board, the key idea here is to tap continuously into the natural daily learning of every individual in the organization.

Browne, in his book Unleashing the Power of Learning,5 comments on BP Amoco as one of the most serious implementers of digital nervous systems, because of their focus on continuous learning across the organization and its hierarch. Enterprise system implementations must take into consideration both micro- and macro-political levels. The micro-political level or internal world of the organization deals with the energies and blockages generated by the existing organization’s capabilities. The macro-political level, or the world outside the organization, deals with the changes in the political, economic, social, technological, and physical environment trends, in an attempt to increase the organization’s effectiveness.

The enterprise system also allows companies to replace their existing information systems, which are often incompatible with one another, with a single, integrated system. The object is to streamline data flows throughout an organization. Software packages, such as those offered by ORACLE, SAP, and IFS, can dramatically improve an organization’s efficiency and bottom line. But despite the many advantages these system provide, you must be careful with the risks they bring, in particular their ability to tie your hands!

Therefore, be it because you need to assess your organization’s capabilities or the enterprise system, make sure to assess the pros and cons of implementing the system very carefully, as any new system introduced can produce unintended and highly disruptive results. Many companies incur huge losses more often than they should when entering uncharted waters, such as new alliances and partnerships, new markets, products or technologies. Often, many of these failures could have been prevented if upper management had approached innovative ventures with the right plan and control tools. Both the board members and executive staff should always be ready to fight the techno-babble of functional specialists, and so the ability to make wise decisions is much improved by the collective critical debate. Discovery-driven planning is also a practical tool to be used at such times, as it acknowledges the difference between planning for a new venture and for a more conventional business. Often, the organization may have to evaluate the bottom line and work its way up the income statement first, before determining the need for a new venture’s profit potential.

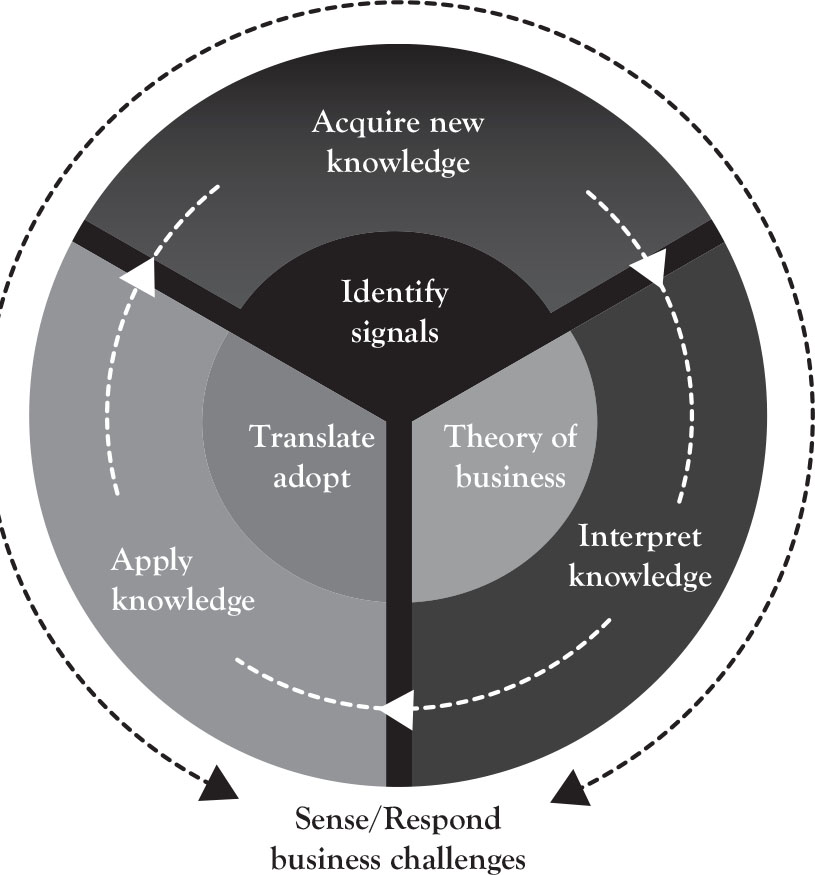

To comply with such action learning process, I believe Figure 5.2 must be modified to provide some “circuit breakers” that would flag learning situations that may lead to pernicious actions for the organization and business as a whole. My model is based on Garvin’s model, as he discusses it in Learning in Action. However, I borrow from Garratt’s concept of an action learning cycle as well, as he discusses it in The Learning Organization: Developing Democracy at Work, to only expand these models to provide validation in every step. Figure 5.3 depicts my view of an action learning cycle for the 21st century learning organization, where time is an asset, mistakes are almost unforgiving, and the inability of an organization to adapt to new environments is synonyms with slow death, as organizations must strive to obsolete themselves every day before the market does it for them.

Figure 5.3. The action learning cycle for the 21st century organizations.

As Figure 5.3 shows, the design of an action learning process is based on simplicity. And simplicity should be viewed as understanding the whole. It should generate excitement, should be easy to view and should be timeless. The role of knowledge workers is to help organizations to go through change. Once upper management, the executive staff, figures out a strategy, the knowledge worker’s job should be to help translate it to the rest of the organization that has to do the work. Building trust and competence for this to become an organizational way of life is not a quick task, and tends to be complex. Pilot actions learning process might be appropriate, followed by public evaluation, so you can build trust, while at the same time, through learning, you build values and behaviors that are rewarded, so that they become part of the organization’s culture.

From this reflective process, depicted in Figure 5.3, learning organizations can break away from the action-fixated cycle of nonlearning, which so bedevils many organizations throughout the world. Typically, individuals tend to avoid a reflective approach to their work and end up jumping into inconsequent and fruitless actions because they already have a hard time just figuring out what they are supposed to do. The 21st century economy, with its reengineering and total quality management (TQM) strategies, with its more leaning approach, has streamlined task work, but knowledge work has become even more cluttered and confusing than ever before. Thus, making fast and right choices, while the economy changes before our eyes every second, is now the toughest part of getting any work done.

In Figure 5.3, projects are integrated into an organization-wide, action learning-base transformation process. This enables learning to be continuously available from each project, but also the organization can see more easily the patterns arising from that learning. The main differentiator in the paradigm I propose is that:

•In the first stage of the learning cycle, the observation stage, individuals should feel comfortable to be in a position of not knowing, so they can actually observe new learning patterns. Pride, ego, seniority aspects, and corporate hierarchy should all be left aside.

•In the second stage, reflection, any new information acquired must pass through a filter of reflection. This is necessary not only to evaluate the relevance of such information, but also to determine how practical, how applicable, such information is for the task at hand or future tasks. In the 21st century economy, there is no power or sense in becoming a human Encyclopedia Britannica, as the most important aspect is to be able to turn knowledge into action, to be able to cope with the change of environments and, ideally, anticipate changes to come.

•In the third stage, hypothesis, individuals should be able to reach a point where they have acquired enough information to formulate a hypothesis. They should be able to have an idea of what they learned, of what they now may know. When testing hypothesis, keep it deductive, rather than inductive, disciplined, rather than playful, and targeted rather than open-ended. The goal here should be to prove, to prepare material for validation during the next stage, experimentation. As pointed out by Lawler,6 managers tend to fail here because they believe they are failing to mesh with the realities of life in their organizations. This is very important so they can go to the experimental stage with a clear focus of what needs to be tested, and what needs to be validated. The question is: what do they think they know? What do they think they are learning?

•In the fourth stage, experimentation, the goal is to achieve a level where you know-why. To learn new information just because doesn’t make sense. With all that has changed in how we work, we need to work smarter, instead of harder and faster. Thus it is important for the learning process that individuals know what they need to learn, what they think they are learning, and why the information is what it is. They must experiment with the new information, they must try it out, so they can trust it, and value can be added to their skills set. Keep in mind that for experiments to be successful, the focus must shift from justification and commitment to skepticism and doubt. Knowledge here should be regarded as provisional, and conclusions as tentative. Otherwise, prevailing views will not be subjected to testing, and experimentation will exist only in name. The same applies to ambiguity, as the higher it is, less objective are the insights taken from the experiment. Notice in Figure 5.3 that experimentation is the second step (number 2) in bridging the knowledge gap in the organization, as individuals are only able to share knowledge they can experiment.

•In the fifth stage, reflection, a first revolution of learning is concluded, as individuals come full circle with the learning process. At this stage they should be able to look back on what they did not know, reflect on what they needed to know, and how they came to formulate a hypothesis about what they may get to know and the results of the experimentation they undertook. Reviews and reflections must be conducted immediately, while the experience and memory is still fresh and data can be validated. Thus, at this stage the new information should have been validated, and a plan to action using this new information should be at work. Otherwise, the process should start again, back to observation.

•In the sixth stage, action, individuals must be able to turn learning into action, to turn know-why into know-how. In the stage before (reflection), the primary problem is passivity, an inability or unwillingness to act on new interpretations. Many times individuals will resist new information and rather restart the learning process, back into observation, as they feel that this information can’t be right. That’s why experimentation is important, but still, people tend to disregard hard facts, when such information means a behavioral change and most people are risk-averse. As Jack Welch of General Electric stated in his book Jack: Straight from the Gut, “change has no constituency.”7 Therefore, to turn leaning into action, a certain level of self-awareness is essential. The results of the experimentation stage, the current practices, must be understood, so action can take place.

•In the seventh stage, recording in the memory (corporate memory), individuals should record their newly acquired know-how, or know-how they learned they already had, in the corporation’s memory bank. This stage is also very important, and its absence or underutilization is partially responsible for what I call knowledge gap. That is what the small number 3 next to the box signifies, as recording and sharing the knowledge they have is vital for knowledge transfer and management, and without it, there is no learning organization. Arnold Kransdorff’s books, Corporate Amnesia8 and Knowledge Management: Begging for a Bigger Role,9 describe many organizations failing to codify and distribute their learning due to a lack of structured corporate memory, the digital nervous system Gates talks about. Without such recording practices, organizations will learn nothing, and forget nothing as well. Such organizations have not learned that history repeats itself, but first as tragedy, then as farce! This stage emphasizes the vital importance of KM implementations and enterprise systems.

•The eighth stage, knowledge transfer, is the final in the learning cycle, but the most important in bridging the knowledge gap within organizations. It’s actually the first step (small number 1 in Figure 5.3), when knowledge is finally institutionalized within the organization. Unfortunately, not many companies take the time to reflect on their experiences and develop lessons for the future. KM professionals and managers in general must help individuals and work teams carefully review the new information learned and distinguish effective from ineffective practice, and also, in stage seven, must record their findings in an accessible form, and in stage eight, disseminate the results to the other individuals in the organization.

Lastly, ask yourself what strategies your organization is adopting to maximize the returns on your knowledge asset. Try to make better use of the knowledge that already exists within your organization by utilizing the action learning cycle discussed above. In my experience, I’ve heard several KM professionals and group leaders lamenting that if only they knew what they knew. It’s common to find individuals in one department or group in the organization reinventing the wheel or failing to solve customers’ problems just because the knowledge they need is elsewhere in the company but not known or accessible to them. Hence, knowledge workers and KM professionals typically focus first on installing or improving an Intranet.

Also consider focusing on innovation as well, the creation of new knowledge and turning ideas into valuable products and services. This is sometimes referred to as knowledge innovation. Don’t confuse it with R&D or creativity though. There is plenty of creativity in organizations; you just need to make sure you don’t lose it, and allow it to flow throughout the organization and find its way to where it can be used. To do that you will need to invest in better innovation, knowledge conversion and transfer, and eventually commercialization processes. This thrust of strategy is the most difficult, yet ultimately has the best potential for improved company performance.

Chapter Summary

This chapter provided an overview of knowledge technologies concepts and its use in organizing knowledge and know-how through business thinking practices. The chapter also discussed the promotion of teamwork as a knowledge transfer tool.