CHAPTER 4

Overview of Decision-Making

As stated earlier, decisions are common in life and in project management. The purpose of decisions, of course, is to accomplish a goal or objective. We normally pick one option or alternative (a course of action or a product) from among several options we are considering. We then proceed to select what we believe to be the best option among the ones we are considering.

People make two types of decisions—(1) instinctive decisions, which are split-second decisions based on immediate perception (and intuition), and (2) thoughtful decisions, which are decisions that are based on our thinking about the consequences of specific decisions. Both types of decisions have their place in our lives. People often use anatomical terms to refer to an instinctual decision, for example, describing a decision made quickly as being made “by the seat of the pants,” “based on a gut feeling,” or “off the top of my head.” With these types of decisions, there is typically much less of a search for good options than there is with thoughtful decisions. Simon (1955) described one version of this process as satisficing; one thinks of an option and assesses whether it is “good enough,” and if it is, one stops thinking about alternatives; if it not good enough, one thinks of another option and repeats the process until an option is good enough.

Project managers will make both types of decisions during the course of their project leadership. While both instinctive decisions and thoughtful decisions are needed, this book focuses on the latter, thoughtful decisions based on cognitive processes—that is, cognitive decision-making.

Cognitive decision-making usually considers many options and addresses their relative pros and cons to some degree. The authors hold that too many people (including project managers) make instinctive decisions when thoughtful decisions would serve them better.

This chapter is intended to help them and others become more conscious of how best to tackle any kind of decision.

This chapter presents the following sections:

![]() The Basics

The Basics

![]() Literary Views of Decision-Making

Literary Views of Decision-Making

![]() Decision Quality

Decision Quality

![]() History of Decision-Making

History of Decision-Making

![]() Approaches to Decision-Making

Approaches to Decision-Making

![]() Decision-Making Methods and Aids

Decision-Making Methods and Aids

![]() Implementing the Decision.

Implementing the Decision.

The Basics

So what is a decision? The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition (2000) provides several definitions, the first three of which are:

The passing of judgment on an issue under consideration.

The act of reaching a conclusion or making up one’s mind.

A conclusion or judgment reached or pronounced.

Howard (1968), who coined the term decision analysis, defines a decision as “an irrevocable allocation of resources.”

Resources that can be allocated irrevocably are money, time, and physical entities such as cars and manufacturing equipment. Recall our modification of Bocquet, Cardinal, and Mekhilef’s (1999) definition of decision: any action taken by an actor(s) that will consume resources and affect other actors in the pursuit of achieving objectives within constraints.

A further revision of our modification of the definition of decision will build upon both of these definitions but will emphasize that decisions are typically made to allocate current resources in the hope of achieving a return in future resources. Thus, we now define a decision as the following: An irrevocable allocation of resources at one point (or at specific points) in time by one or more actors, in order to affect the world and other actors so as obtain a more desired state in the future for the original actors.

The future in this definition might be seconds, minutes, or hours—or it could be months and years. For issues regarding nuclear power, for example, the benefits might be obtained in years and decades, but the potential negative effects might not be realized for generations.

In Chapter 2, we described types of decisions that pertain to project management and its life cycle: decisions oriented to the conception of the project, how to do the feasibility analyses, what plans and plan steps to create, how and when to perform detailed work, what milestones and gates to create for controlling, and how to terminate the project. In these types of decisions, and in all decision situations, the following three elements are always present:

Alternatives or things the decision maker can choose: If there is only one alternative available, the decision maker does not have a decision but a problem (either a good one or bad one). Problems often can be turned into decisions by the decision maker’s creativity, which could include accepting something that is less preferred on one objective to gain on another objective.

Values that tell the decision maker which option might be most or least preferred: Values are the hardest part of decision-making for most decision makers because values are purely subjective—they pertain to what people care about. We are all used to making cost versus performance trade-offs when we buy something at the store; that is, should we get the store-brand item or the namebrand item that costs more but presumably has higher reliability or better taste? Project managers should already be familiar with the cost-time-performance trade-offs that are commonly part of introductory project management courses.

A well-known maxim of success in project management is that a stranger should be able to walk through the project management office asking what is really important to this project and find that every answer will be the same and will contain no more than three or four topics. Nonetheless, even in successful projects it is common for the key people on the program not to know what the key cost, schedule, or performance parameters are. If the project manager and his senior people have not agreed on what the key factors are and communicated this information to everyone in the project office and to the contractors, then many decisions may be made at cross purposes to each other.

As all project managers know, a decision that is oriented toward project success can have negative and positive effects on both the people that are part of the organization and the project office within the larger organization’s context. So, in these cases, the issues of people and organization must also be included in the value structure, along with those issues of project success.

Knowledge (facts, guesses, ideas, etc.) about the world now and in the future: Finally, there is knowledge. What do we know for sure and what do we not know? For those things that are not known, how uncertain about the answers are we? Are there known unknowns and unknown unknowns? Good project managers are able to identify many of the latter and turn them into the former. How do we deal with unknowns of any type in decision-making? This is where risks come from; risk is another topic with which project managers should be familiar.

Chapter 6 describes how to create a decision frame that addresses the alternatives, values, and knowledge for a decision, as well as the context associated with the decision. Chapter 7 covers the topics of values and knowledge in more detail.

Literary Views of Decision-Making

Dogbert is a familiar cartoon character in the Dilbert cartoon strip by Scott Adams. Dogbert has identified any number of approaches to decision-making over the years:

![]() Act confused.

Act confused.

![]() Form a task force of people who are too busy to meet.

Form a task force of people who are too busy to meet.

![]() Send employees to find more data.

Send employees to find more data.

![]() Lose documents submitted for your approval.

Lose documents submitted for your approval.

![]() Say you are waiting for some other manager to “get up to speed.”

Say you are waiting for some other manager to “get up to speed.”

![]() Make illegible margin scrawls on the documents requiring your decision.

Make illegible margin scrawls on the documents requiring your decision.

Decisions have also been addressed in classical literature for centuries. The Roman statesman and philosopher named Seneca said, within decades of Christ’s birth, “If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favorable.” Shakespeare in 1602 addressed the ultimate decision faced by people in Hamlet—“To be or not to be. …” Lewis Carroll, paraphrasing Seneca for a new and younger audience, wrote in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865:

One day Alice came to a fork in the road and saw a Cheshire cat in a tree.

“Which road do I take?” she asked.

“Where do you want to go?” was his response.

“I don’t know,” Alice answered.

“Then,” said the cat, “it doesn’t matter.”

Frost (1916) continued the association between decisions and selecting a road/path/port when he wrote the following well-known poem:

The Road Not Taken

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Here Frost points out a defining issue in the study of decision-making: When we make a decision, it is possible with hindsight to evaluate what happened as a result of that decision. But it is not possible to evaluate what might have happened if our decision had been different because we can never be sure about what might have happened at that time. Sometimes there can be little difference between the choices. At other times there can be a very big difference. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to predict whether a difference will be small or large. There has been little empirical research on comparing one decision or decision process to another because it is not possible to compare the outcomes of the selected choice to the those of choices that were not selected.

Perhaps the most relevant quote for this book on decision-making for project managers is by Rosa Parks, the African American who was ordered to give up her seat on a bus for a white person by the bus driver, but refused. She says in her book Quiet Strength (1994):

When one’s mind is made up, this diminishes fear; knowing what must be done does away with fear.

Decision Quality

Is there a way to measure decision quality? It is always tempting to say that getting a good outcome after a decision is made means that a good decision was made. The converse of this is that a bad decision means that a bad outcome is obtained. But consider the following strategies used by two different project managers, each facing a decision about whom to select for a key position in the project management office:

Jack: I chose Bill because he seemed affable and went to a good school. Bill was the first person to respond to my ad.

Jill: I chose Ed because he met my major criteria concerning people skills, knowledge of the key topics needed for the job, experience in the field, and contacts with other people that could prove useful. I interviewed a dozen people, asked my deputy to screen two dozen applications, asked several of my key people to talk to the four most promising people, and asked my boss to interview the two best candidates.

Now, which of these decision processes do you think was best? We think Jill has the best defined decision process and has thought about the pros and cons of the candidates in more detail and with more clarity. Is Ed (the person selected by Jill) guaranteed to be a success in his position? No. Could Bill perform far better than expected and end up taking Jack’s job when Jack gets promoted? Yes. But which of these decision processes is most likely to produce the best outcome? While there is no appropriate way (at this time) to do controlled research on this topic, the authors (and many other decision analysis professionals) believe that, by and large, good decision-making processes will generate a higher percentage of good outcomes than will poor decision-making processes. Good decisions must be based on the process that was used, not the outcome that was obtained.

Good outcomes can and do result from low-quality decision processes, and bad outcomes occur more often than we would like when high-quality decision processes are followed. Figure 4-1 illustrates the philosophy that good decision-making is the careful generation and consideration of the alternatives, values, and knowledge associated with the choice. Inherent in this careful consideration are the examination of trade-offs across multiple objectives, across time periods, and across risk positions. Consideration must be given to postponing the decision in order to gather more information; but consideration here only means that the decision is postponed if it is reasonably likely that valuable information could be collected.

In the real world, the person or group involved in actually making decisions considers the current decision, selects an alternative, implements it, and discovers the outcomes. However, there is a lot more to making a “good” decision. First, we should examine what decisions could be made now (e.g., hire more personnel, create a research program focused on a key technology) and select the appropriate decision to address (e.g., choose to create the research program because it has more immediate consequences for postponing and there are some important differences among the research programs under consideration). This is called making the meta-decision—deciding what decision to make. Next, it is time to identify our values or objectives for this decision and a reasonable set of alternatives, each of which could fulfill those objectives. Then, some type of evaluation of the alternatives relative to the objectives is conducted, considering any uncertainties. This evaluation should guide the decision maker in finding the best (or at least a very good) alternative.

FIGURE 4-1: Philosophy of Good Decision-Making

Before implementing the alternative, the decision maker should ask if there is any important information that could be collected that might change the selection of the desired alternative or how that alternative is to be implemented. The cost and delay associated with this information collection should also be considered. When all relevant information has been collected and further considered, it is time to implement the selected alternative. In fact, a lot of activity and further decision-making are wrapped up in the task of implementation.

At one extreme, there is the case where the decision maker makes a bet at the gaming table and waits to see the result. Decision makers in real life who use this approach are bound to be disappointed quite often. At the other extreme is JR (the rich rascal from the old Dallas television show); JR would bribe and kill anyone who stood between him and a good outcome. This is not the kind of behavior that leads to good outcomes in the long-run; jail or death is the most likely long-run outcome here. Standing somewhere in the middle, a good decision maker determines who has the power to veto and makes sure they are in agreement or that compromise is possible. The decision maker also identifies who could slow the decision process down or cause changes to be made and then “sells” them on the proposed solution or makes appropriate compromises. The random activities that could occur are also identified, and risk mitigation plans are put in place in case they are needed. Much of this can be done mentally for simple, low-risk decisions. But for high-stakes decisions, a more formal process is appropriate.

Figure 4-2 depicts the elements of good decision-making for a current, single decision. The boxes in Figure 4-2 represent the two extremes (good versus bad) of four important concepts (Decisions, Random Events, Implementation, and Outcomes). The point of this figure is that good or bad outcomes can be caused by some combination of random events, the decision made by the project manager, and the implementation effort associated with the decision. It is possible to find cases of great decisions, well-conceived and well-conducted implementation efforts, and positive unforeseen events that still resulted in less-than-desired outcomes. Similarly, there are a few poorly made decisions with poor or no implementation efforts and disastrous unforeseen events that resulted in positive outcomes for the decision maker. The point remains that we are not guaranteed success by being smart and industrious, but we do have a far greater chance of success if we are smart and industrious.

FIGURE 4-2: Good versus Bad Decisions and Outcomes

A good decision must include the following:

![]() A good decision-making structure for gathering and integrating information, finding the preferred decision, and creating and conducting the implementation efforts

A good decision-making structure for gathering and integrating information, finding the preferred decision, and creating and conducting the implementation efforts

![]() A good review of the possible decisions (the topics to be addressed) and the selection of the appropriate decision given the situation; this could be a good meta-decision (a decision about the right decision to be considered)

A good review of the possible decisions (the topics to be addressed) and the selection of the appropriate decision given the situation; this could be a good meta-decision (a decision about the right decision to be considered)

![]() A good process for finding the preferred alternative among the many that are being considered.

A good process for finding the preferred alternative among the many that are being considered.

The next section, “History of Decision-Making,” includes a description of the kind of decision-making structure that has been developed in some military organizations to ensure that a set of activities are in place for making decisions in an evolving situation. Such a process can be found in some project management organizations. The delineation of project management decisions and when they are relevant was presented in Chapter 2 and will be dealt with again in Chapter 5. A good decision-making process such as the process presented in Chapter 1 attempts to do the following:

![]() Find all of the reasonably attractive alternatives.

Find all of the reasonably attractive alternatives.

![]() Define clearly the objectives by which the decision maker should select the preferred alternative.

Define clearly the objectives by which the decision maker should select the preferred alternative.

![]() Find the best or a really good alternative by examining trade-offs across these criteria, across time periods, and across risk positions.

Find the best or a really good alternative by examining trade-offs across these criteria, across time periods, and across risk positions.

![]() Evaluate the value of postponing the decision to collect more information.

Evaluate the value of postponing the decision to collect more information.

Before describing decision structures, we are going to consider the issue of how to deal with decisions that are related and occur across a period of time. The first perspective is a systems view (Figure 4-3) that adds a monitoring process to the elements of Figure 4-2. The point of this figure is that as we move from one decision to another we need to have a monitoring process in place in order to determine whether the outcomes we desire for previous decisions are occurring. If not, we must address these issues as part of our implementation plan or revisit our earlier decisions and make adjustments to the extent possible—or we must adjust our later decisions.

We can extend our time horizon even further and take a meta-systems view that includes trying to learn from our past. There is a vast literature now on learning organizations and projects (Matheson and Matheson 1998). Figure 4-4 depicts the role of learning in the process of achieving good outcomes as part of decision-making. A good learning process should affect our monitoring activities, implementation efforts, and future decisions. This learning will not only affect what alternatives we prefer in the future but also the meta-decision process that leads us to decide which decisions are most appropriate to consider.

FIGURE 4-3: A Systems View of the Factors Affecting Good Outcomes

FIGURE 4-4: A Meta-Systems View of the Factors Affecting Good Outcomes

History of Decision-Making

The history of human decision-making is as long as human life. The next three figures present highlights from the history of decision-making based upon publications by Buchanan and O’Connell (2006) and Smith and von Winterfeldt (2004). Figure 4-5 shows the history prior to the Industrial Age, beginning with voting in Athens and critical military decisions. The development of probability concepts and theories began near the end of this period. A famous quote from Napoleon in 1804 ends this period.

FIGURE 4-5: Highlights in the History of Decision-Making: 5th Century BC-1804

Figure 4-6 presents highlights from the history of decision-making from after the Industrial Age began through the eight-year period after World War II. Early developments in this period were by economists. Before, during, and after World War II, the advances came from the integration of probability theory and economic theories related to value and risk.

FIGURE 4-6: Highlights in the History of Decision-Making: 1881-1954

Highlights from the history of decision-making during the transition from the Industrial Age through the Information Age are shown in Figure 4-7. The work since the middle 1950s has focused on quantitative methods for analyzing decisions, including value trade-offs, risk and time tradeoffs, and uncertainty. This book does not focus on this material but provides insights for decision-making based on much of this work and related psychological research about the problems real decision makers have.

FIGURE 4-7: Highlights in the History of Decision-Making: 1966-1992

Approaches to Decision-Making

Many decisions are simple, preprogrammed, or already made. For example, project managers do take a considerable amount of time to think long and hard about what software to use to schedule project tasks. Many other decisions are not as structured and are more strategic in nature, such as choosing whether to invest in a particular project. Scholars of decision-making have long differentiated between structured and unstructured decisions. Structured decisions are those decisions for which the decision maker or an organization has a decision process. Examples include new product development (for firms in the product development business) and buying a new car or house. Unstructured decisions are those that are made without using any defined process, such as how to deal with a sudden illness or how to react to a new product that was unexpectedly introduced by an unexpected competitor. Mintzberg et al. (1976) proposed a process for unstructured decisions. Buede and Ferrell (1993) compared several such processes in Table 4-1. Interestingly, by defining a process for unstructured decisions, Dewey (1933), Simon (1965), Mintzberg et al. (1976), and Buede and Ferrell (1993) are, in fact, turning unstructured decisions into structured decisions, at least within the confines of the table.

TABLE 4-1: Processes for Unstructured Decisions

Mintzberg and Westley (2001) suggest three ways to approach a decision: “Thinking first,” “Seeing first,” and “Doing first.” “Thinking first” is the traditionally analytical process: Define the problem, diagnose its causes, identify objectives, brainstorm solution alternatives, perform an analysis, and decide.

“Seeing first” is described as a four-step creative discovery process: preparation ≫ incubation ≫ illumination ≫ verification. This description of “seeing first” suggests that the problem has been defined and diagnosed, and that the perceptual discovery of a solution that is clearly good enough completes the process. This description of “seeing first” suggests that the problem has been defined and diagnosed, and that the perceptual discovery of a solution that is clearly good enough completes the process.

However, the workshops described by Mintzberg and Westley include drawing a collage for the issue as an implementation of “seeing first.” This collage combines defining the problem, diagnosing the problem, and examining several solutions. This description suggests an analytical process focused on the visual rather than thinking. This drawing-oriented visual process emphasizes communication and obtaining buy-in. Mintzberg and Westley provide summaries of the three approaches as consistent with this last description of “seeing first” (Table 4-2).

“Doing first” involves trial and error or experimentation. This experimentation is best when we do not feel sure about the pros and cons of each alternative, so we select one or several actions and try them out, gaining information about how well each one works. This information then allows us to transition to the thinking or seeing approach.

Table 4-2 provides a comparison of the three approaches of Mintzberg and Westley (2001).

TABLE 4-2: Comparison of “Thinking, Seeing, and Doing First”

| “Thinking First” qualities | “Seeing First” qualities | “Doing First” qualities |

| Science | Art | Craft |

| Planning, programming | Visioning, imagining | Venturing, learning |

| The verbal | The visual | The visceral |

| Facts | Ideas | Experiences |

Table 4-3 summarizes these three approaches (Mintzberg and Westley 2001).

TABLE 4-3: Summary of “Thinking, Seeing, and Doing First”

| “Thinking First” works best when | “Seeing First” works best when | “Doing First” works best when |

| The issue is clear | Many elements have to be combined into creative solutions | The situation is novel and confusing |

| The data are reliable | Commitment to those solutions is key | Complicated specifications would get in the way |

| The context is structured Thoughts can be pinned down Discipline can be applied | Communication across boundaries is essential | A few simple relationship rules can help |

| e.g., an established production process | e.g., new product development | e.g., facing a disruptive technology |

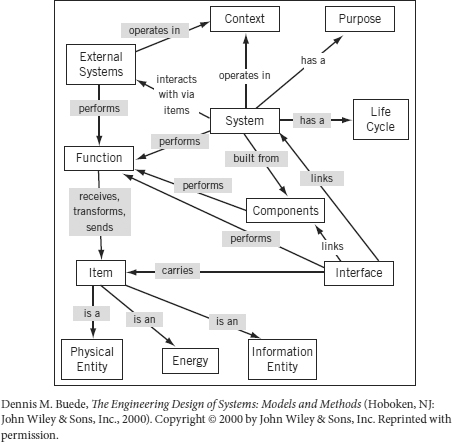

An example of a “seeing first” decision process is the use of cognitive maps, as proposed by Axelrod (1976). A cognitive map is a directed graph (nodes and arcs) that shows concepts or ideas as nodes. The arcs then signify some kind of relationships between the nodes. The relationships can be based on relationships or sequential timing or some deeper concept such as causation or implication. Figure 4-8 provides a cognitive map-based on some concepts from systems engineering (Buede 2000). Cognitive maps can be a significant augmentation to the communication process. The Observe - Orient - Decide - Act (OODA) loop process presented in two figures in the next section are also examples of a concept map.

FIGURE 4-8: Concept Map from Systems Engineering

Decision-Making Structures for “Thinking First” Tasks

Decisions that permit reflection by the project manager should be made by means of some cognitive process. Such a process should consist of steps by which the possible alternatives are reviewed, objectives are outlined, and careful consideration of trade-offs is completed. Some decisions that can be made over hours or longer time frames are made once and never revisited; other decisions are made periodically based upon new information. Table 4-4 illustrates some simple and complex decisions in each of these two categories.

TABLE 4-4: Sample “Thinking First” Decisions

| Simple | Complex | |

| One-Time Decision | Buying basic IT hardware and software Hiring a new employee Deciding who should be sent to training Deciding the project organization |

Selecting an architecture design for a new product Deciding what research or risk mitigation efforts should be funded Buying advanced technology for IT support Hiring a senior member of the project staff during a crisis situation |

| Sequential Decision | Deciding whether to accept the current work product or pass it back for improvement Deciding project risk Deciding how the project will be managed |

Deciding on yearly planning/budgeting Determining a project development strategy Revisiting early project termination Proceeding to the next phase |

A truly great example of “thinking first” was created by Colonel John Boyd of the U.S. Air Force, who developed an action selection strategy that was first applied to air-to-air combat in the Korean War. This strategy was to be implemented by U.S. pilots, who were informed that enemy pilots were using a similar strategy. Actions included shooting and employing maneuvers that would be deceptive and provide ambiguous cues to the enemy, thus making the enemy’s decision process more difficult. Information was valuable throughout this process in that the decision was to be based on a clear view of the situation or context. Boyd called this process the OODA loop. Boyd and others later realized that the OODA loop was a general decision-making process that is as relevant to business activities in government and industry as it is to warfare (Richards 2002 and 2004).

Boyd’s action selection strategy included the following: “Observe” means to look for and gather relevant information. “Orient” means to make sense of the information and establish the context for the decision; this is often called situation awareness today. Included in “Orient” is addressing the meta-decision. “Decide” means making a decision using a process of evaluating the alternatives with respect to the objectives in light of the facts and existing uncertainties. “Act” means to implement the decision, including setting up a monitoring process that determines what information would be the most valuable to collect. This process would be repeated as often as necessary (Figure 4-9). Other similar cycles exist, such as the Plan-Do-Check-Act (often called the Shewhart or Deming cycle). That cycle dates back to the 1920s with Shewhart (1939) and the 1950s with Deming.

FIGURE 4-9: Simple Representation of the OODA Loop

Figure 4-10 provides a more detailed view of the OODA loop, showing (1) three generic types of information that feed the decision maker’s observations, (2) five elements of the situation that must be addressed, and (3) feedback loops from three sources (the decision, the action, and interactions between the decision maker and the rest of the world).

FIGURE 4-10: More Detailed OODA Loop

The three categories of information, which are shown on the left side of Figure 4-10 and feed the observation process, are quite carefully crafted. By carefully crafted we mean they nicely represent all possible types of information available to a decision maker. The top two categories (outside information and unfolding circumstances) come from outside the decision process. Outside information includes the information that provides context to the decision, such as what is going on in other decision contexts that might be relevant to this particular decision context. Information about unfolding circumstances captures information from outside sources that is directly related to this decision situation, such as available resources that were expected to arrive. The most obvious category is information related to the implementation of the selected action and its interaction with the world. In air-to-air combat, this information would include sensor reports about other aircraft in the area. For a project manager, this information includes reports from the appropriate organizations about cost, schedule, and performance; reports from other personnel about cost, schedule, and performance; and other reports about the budgets and expected performance parameters desired by management.

The second category, unfolding circumstances, includes technology developments and associated reports, changes in the marketplace associated with the focus of the project that might affect what the project should be doing, and changes in the organization responsible for the project. Consider the following case study.

CASE STUDY![]()

Iridium

“Iridium” was the name of a product created by a consortium of companies from around the world in 1990 to create a mobile phone that would enable its owner to talk to anyone anywhere in the world, at any time. By the time the product was ready, a large portion of the world’s population had mobile phones that were less capable but much more usable and less expensive. A $5 billion investment was sold for $25 million in 2001 because the company could not find customers willing to pay $3,000 for the brick-like phone and $7 per minute for calls.

The changing marketplace faced by the Iridium project was completely ignored by the project manager and the firms contributing money to the project. This project illustrates the importance of paying close attention to unfolding circumstances.

The last category of outside information could include reports from experts associated with activities not associated with the unfolding interaction.

Boyd stressed the importance of the “Orient” step in the OODA loop to shape or interpret the information coming from the “Observe” step. The purpose of the “Orient” step is to get the decision maker to review the project manager’s current status, the most important, current objectives, and the most operationally relevant strategy. Most project managers are familiar with SWOT analysis—strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Strengths and weaknesses are internally focused; opportunities and threats are externally focused. A SWOT analysis is the type of activity that should be undertaken during the “Orient” step. Currently, many people talk about doing “situation assessment” and achieving “situation awareness,” which is also part of “Orient.”

We discussed the importance of addressing the meta-decision when we addressed Figure 4-1—deciding what decision to address. This meta-decision analysis also fits here. Payne, Bettman, and Johnson (1993) address the importance of orientation, situation awareness, and meta-decisions in The Adaptive Decision Maker. Consider the following case study (Sculley and Byrne 1987).

CASE STUDY![]()

Pepsi

An example of a meta-decision is that faced by Pepsi when its management was trying to gain market share on Coca Cola. According to Sculley (CEO of Pepsi at the time), Coca Cola had a tremendous advantage in market share that could be largely traced to the shape of the Coca Cola bottle. Pepsi tried to counter the bottle disadvantage but to no avail. It was not until they did an experiment involving how much soda consumers would consume that they realized they could package Pepsi in larger containers and consumers would purchase these larger containers. The larger containers overcame the advantage of the shape of the Coca Cola bottle.

Here we must caution the reader about the overwhelming tendency people have to deceive themselves about reality. There has been a great deal of research dealing with human biases and heuristics in decisionmaking and other judgmental tasks; we review this material in Chapter 8. Some of these important biases that are relevant for consideration within the OODA loop follow:

![]() Selective search for evidence: People generally seek information that will confirm their beliefs rather than seeking evidence that will prove themselves wrong. Science teaches us that we can never prove a proposition by accumulating more and more positive examples that it is true, but we can disprove a proposition by finding one instance where it is false. Disconfirming evidence is therefore much more valuable than confirming evidence and should have the effect of reducing our overconfidence.

Selective search for evidence: People generally seek information that will confirm their beliefs rather than seeking evidence that will prove themselves wrong. Science teaches us that we can never prove a proposition by accumulating more and more positive examples that it is true, but we can disprove a proposition by finding one instance where it is false. Disconfirming evidence is therefore much more valuable than confirming evidence and should have the effect of reducing our overconfidence.

![]() Anchoring and adjustment: People will often start with an initial value and adjust away from it to obtain related values. In general, such adjustments are insufficient, being biased toward the starting value.

Anchoring and adjustment: People will often start with an initial value and adjust away from it to obtain related values. In general, such adjustments are insufficient, being biased toward the starting value.

![]() Availability: People tend to attach higher probability to events that they recall readily. Recent events, or those that are more salient to the individual, impact the individual’s perception of the frequency of such events. How readily an event can be imagined can also be a factor. For example, accidents that make the news are judged more likely to occur than accidents that are just as likely but do not tend to make the news. Specifically, a death by a person shooting a gun is about as likely as a death by accidental falling (in 2003); however, most people think the former is much more likely than the latter because shootings appear in the news more often.

Availability: People tend to attach higher probability to events that they recall readily. Recent events, or those that are more salient to the individual, impact the individual’s perception of the frequency of such events. How readily an event can be imagined can also be a factor. For example, accidents that make the news are judged more likely to occur than accidents that are just as likely but do not tend to make the news. Specifically, a death by a person shooting a gun is about as likely as a death by accidental falling (in 2003); however, most people think the former is much more likely than the latter because shootings appear in the news more often.

As discussed in Chapter 2, three elements are always present in a decision situation: (1) the alternatives, (2) the values associated with the objectives, and (3) knowledge about the world now and in the future. This third element clearly comes from the “Orient” stage, which is derived from the “Observe” stage. In fact, the alternatives also are derived from the “Orient” stage.

Some key points Boyd made in his many briefings (some as long as 15 hours) and points made by others are:

![]() Use as many information sources as possible, but recognize the limits of each information source and the possibility of deception by others, which could corrupt the information. Project managers have to be concerned about the credibility of their information sources as well as the possibility that one or more sources might be deceptive.

Use as many information sources as possible, but recognize the limits of each information source and the possibility of deception by others, which could corrupt the information. Project managers have to be concerned about the credibility of their information sources as well as the possibility that one or more sources might be deceptive.

![]() Place the information that is available into the context of the situation (“Orient”), because the same information in different contexts can have dramatically different meanings.

Place the information that is available into the context of the situation (“Orient”), because the same information in different contexts can have dramatically different meanings.

![]() Examine the trade-offs among the multiple objectives available because these trade-offs can change with time due to the changing context. Clarify these trade-offs with the current context and make sure that others involved in the decision also understand the trade-offs.

Examine the trade-offs among the multiple objectives available because these trade-offs can change with time due to the changing context. Clarify these trade-offs with the current context and make sure that others involved in the decision also understand the trade-offs.

![]() Include in the implementation of your decision a monitoring program that uses available information-gathering resources so that the success or failure of the decision and its implementation can be tracked over time as part of the “Orient” step. Follow-up decisions can modify this implementation or change it entirely.

Include in the implementation of your decision a monitoring program that uses available information-gathering resources so that the success or failure of the decision and its implementation can be tracked over time as part of the “Orient” step. Follow-up decisions can modify this implementation or change it entirely.

Decision-Making Structures for “Seeing First” Tasks

There are many situations in life in which one must make a split-second (or instinctive) decision based on the demands of the situation. Klein (1998) has studied many of these cases and termed the quick (or “seeing”) decision process recognition-primed decision (often called RPD). Figure 4-11 presents a process model for RPD (Klein 1998). The figure begins with the context and situation as background. Something happens. For a project manager, this can be a crisis or an opportunity that needs a reaction quickly. While not life-threatening, as were situations for the firefighters or law enforcement officers studied by Klein, these kinds of situations can be project-threatening or opportunities for success.

FIGURE 4-11: Process Model for Recognition-Primed Decision-Making

The decision maker uses a set of cues and expectancies to recognize the context and the situation. If the situation is familiar to the project manager (follow the right side of Figure 4-11 from top to bottom with no side loops), the preferred choice will be found by a process of evaluating a short list of possible options based on the project goals. As stated early in this chapter, Simon (1955) called this satisficing. A last check is made to ensure that the selected reaction will work; if so, implementation begins.

Now what happens if recognition does not occur initially? The project manager moves to the left of Figure 4-11 after deciding that the situation is not typical. A diagnosis phase is initiated with an attempt to use features of the situation to try to recognize or find an analogy that can aid recognition. The decision maker then builds a story around this recognition. If successful, the project manager moves back to the recognition and option selection process.

If there is a problem with recognition after the recognition and option selection process has been entered, the anomaly is defined and the project manager moves back to diagnosis or even reverts to reassessing the situation.

Finally, if the project manager has selected an action but later determines that it might not work, options not selected can be revisited and attempts to find the next best one can be made. This is repeated until the option that the project manager believes will work is found.

Decision-Making Structures for “Doing First” Tasks

The concept of “doing first” involves experimentation for the purposes of gathering information for learning and iterating toward a good decision solution. We have already described the “thinking first” and “seeing first” processes. “Doing first” can result from either one and is typically not initiated without first being part of either “thinking first” or “seeing first” For example, if the decision maker is thinking about competing alternatives and weighing their pros and cons, “doing first” might be selected because there is not enough information to define pros and cons. By selecting “doing first” as an alternative, the decision maker is gathering information about one or more of the possible alternatives so that a better decision can be made later. Similarly, during a “seeing first” decision process, the decision maker might recollect that “doing first” worked very well in a similar situation and select it as the alternative course of action. Thus, our suggestion is to decide whether “doing first” makes sense within either a cognitive or a perceptive process and then use the appropriate process.

Decision-Making Methods and Aids

People tend to rely upon heuristics or “rules of thumb” to make decisions; however, not all decisions can be made that simply because too many variables and factors exist along with the uncertainty that characterizes most project management decisions. Heuristics are simplification strategies (they save time and effort) and in many cases work reasonably well, but sometimes they can inject faulty judgment or cognitive bias into the process. Some biases are the straightforward product of laziness and inattentiveness, and although heuristics typically yield accurate judgments, they can produce biased and erroneous judgments also.

In addition to a decision process, there are many useful methods that help a decision maker in making the best decision. All methods can be categorized as qualitative (making decisions based on concepts or aggregated comparisons, such as good or poor), or quantitative (making decisions based on numerical inputs and numerical comparisons). Some decision makers prefer qualitative methods, while others prefer quantitative methods. Individuals without mathematical backgrounds might prefer a qualitative approach, but a qualitative approach should never be the default. In many cases, a quantitative approach is preferred.

Decision-making aids help stakeholders as well as project managers understand difficult choices and trade-offs. Decision trees incorporate risk and uncertainty. Decision matrices and tables screen solutions. Other aids include (1) decision hierarchies, (2) influence diagrams, (3) spreadsheets, (4) tornado diagrams, (5) risk profiles, and (6) sensitivity analyses. Not all aids apply to project management, and the ones chosen should be appropriate for project managers. The essential objective of a decision aid is to help communicate decisions to stakeholders and to help the project meet cost, schedule, and product expectations. Decisions trees are no stranger to project management. An explanation of decision trees, tornado diagrams, and risk profiles is presented in Appendix C.

Implementing the Decision

The implementation of a decision is perhaps the most important task for the project manager. Managers are sometimes more interested in making a decision and then evaluating the result to determine if the decision achieved the stated purpose than they are in implementing it. There is often an obsession with making decisions and leaving the implementation to the lower levels in the organization. Decisions often require interpretation by management to be adequately implemented; if management doesn’t do that, the decision can be improperly implemented and can fail. Implementing a decision requires as much planning and management oversight as planning the decision and making it. Project managers must account for whether the decision was implemented or if the decision changed during implementation—a result that can create a difference between what was decided and what was implemented.

The real value of a decision becomes apparent only after implementation, and yet implementation cannot begin until goals have been set, the decision has been approved, personnel have been assigned, and funds have been allocated. People often think that after decisions are made, implementation is quite straightforward and requires no guidance. In practice, however, both the decision and implementation of the decision must be planned—and should be planned concurrently. In addition, the implementation of the decision should be evaluated to determine if (1) the stated purpose of the decision was achieved, (2) the stated purpose of the decision was not achieved, or (3) improper implementation methods have resulted in a need for an extended completion time.

General rules for implementation are:

Verify that the decision you have chosen is a good decision.

Work out how to implement your decision.

Work out how to monitor its effectiveness.

Commit yourself to your decision and act on it.

Avoiding Failure during Implementation

In project management, it is not enough to select the best decision alternative. If the decision is not implemented successfully, a favorable outcome is unlikely. After a decision has been made, appropriate action must be taken to ensure that the decision will be carried out as planned. Decisions have routinely failed to be implemented due to a lack of resources, such as necessary funds, space, or staff, or some other failure, such as inadequate supervision of subordinates and employees (Harrison 1987). Proper planning can effectively eliminate such failures.

Implementing the decision is a complex function and the one in which most project errors occur. Alexander H. Cornell captures the complexity of this function (Harrison 1987):

Constraints surface in the Implementation Phase, constraints of a physical, administrative, distributional fairness and political nature, in addition to the ever-present financial and other resource constraints …. The “adversary process” is triggered and if care is not taken, a good [decision] can be negated by those who attack it …. This can be an agonizing period for one who may have devoted his or her very best to the [decision], but it is the real world.

Then, too, it is during the phases of implementation … that other unforeseen effects appear. Things that were believed measurable may prove not to be so; unknowns and uncertainties appear which require adjustments … —all of which are designed to reduce the amount of uncertainty and to make known the unknown; to treat side effects and spillovers which may not have been foreseen, especially the important external ones.

There are thus many obstacles to the successful implementation of managerial decisions. Some are known and others appear during implementation. Chief among these obstacles are (1) the perception of the reduced importance of a decision after it has been made and implemented, (2) the control of the outcome of a decision by those who were not involved in its making, and (3) the development of new situations and problems affecting the quality of the implementation that command the attention of the decision makers after the choice has been implemented (Harrison 1987). Another main obstacle is the lack of planning for implementation early in the decision-making process. It is often the case that implementation is not considered until after the choice has been made. When this occurs, the project can absorb unnecessary amounts of time and valuable resources as the project manager hurriedly tries to arrange for implementation.

Monitoring, Assessment, and Control

Outcomes rarely occur as planners have envisioned them. Thus, a follow-up and control process should be established to ensure the project remains on track during implementation. This process should consist of three steps: (1) monitoring, (2) assessment, and (3) control. These steps make up the closed-loop process shown in Figure 4-12. The purpose of this process is to provide continuous testing of actual results to determine if managerial objectives defined early in the decision-making process have been achieved. This process becomes the sanity check for the project during the implementation function.

FIGURE 4-12: Monitoring-Assessments-Control loop

Monitoring is the collecting, recording, and reporting of project information that is important to the project manager and other relevant stakeholders (Mantel, Meredith, Shafer, and Sutton 2001). The purpose of monitoring is to ensure that all team members have the information and resources required to exercise control over the project. The key to designing a monitoring system is identifying the special characteristics of performance, cost, and schedule that need to be controlled to achieve project objectives. All decisions will affect the performance, cost, and schedule elements of the project. In addition to designing a monitoring system, the exact boundaries within which these characteristics should be controlled must be determined.

Assessments are critical in monitoring outcomes in order to determine what changes are warranted throughout the implementation function. Assessing is the evaluation of monitored data and information to determine whether the project is progressing according to schedule, budget, and required performance. This step should occur repeatedly. The information gained in this step is referred to as feedback. Feedback is used to compare actual performance to expected performance. When the actual performance does not align with the expected performance, there can be many reasons: the decision itself, poor implementation, or a lack of resources. If the decision itself is the problem, it might be necessary to consider a new decision.

Control is the use of the monitored data and assessment information to develop actions to bring actual project performance into agreement with planned performance (Mantel, Meredith, Shafer, and Sutton 2001). The process of control begins with a clear view of the project objectives. Criteria are defined to reflect more specific aspects of project objectives. Performance measures are then developed for each criterion. The performance measures become the control standards to determine whether the project is healthy. If the project is unhealthy, controls are necessary to correct deviations from the standard that is expected. Corrective action can include (1) reordering operations, (2) redirecting personnel, or (3) resetting the managerial objectives (Harrison 1987).

This chapter began with defining a decision as the selection of one or more alternatives from many, based on one’s preferences over a set of objectives and given what is known at the time. Knowing one’s objectives and searching for information that will help differentiate alternatives are important aspects of making a decision. Finding the best set of possible alternatives is also very critical. Several literary perspectives on decision-making and important decisions made by people in the past were presented to set the stage for further discussion.

We concentrated on what good decision-making means: Good decisions must be based on the process that was used, not the outcome that was obtained. It is easy to fall into the trap of evaluating a decision based on the outcome, but the decision maker seldom has control of the outcome. Besides focusing on finding good alternatives, knowing one’s objectives and values, and collecting information that differentiates alternatives, there are other aspects of decision-making that must be considered, such as checking to determine if there is easily collected information that could change the decision, making sure the decision being made is the most appropriate decision to make at this time, and considering the impact this decision is likely to have on other related decisions.

Decision makers can be too relaxed about their decisions—waiting to see what happens. Good decision makers must be aware of what people and events can be influenced and must use their time to “sell” their desired solution to the problem. Of course, this desired solution is the decision problem that must be thoughtfully considered in light of the decision maker’s values and knowledge about the state of the world. This chapter also related the concepts of “implementation” and “random events” to the previous concepts of “good … bad decisions” and “good … bad outcomes.” Building a monitoring system and learning from experience were also added as key decision-making concepts. We expressed the belief that many students of decision-making have adopted—good decision-making processes will generate a higher percentage of good outcomes than will poor decision-making processes.

A short history of the many topics associated with decision-making was presented to give the reader the sense that this is a topic that has been addressed in many thoughtful ways by many people over the centuries.

There are at least three major approaches to decision-making: “thinking first,” “seeing first,” and “doing first.” Each of these is appropriate for specific situations. Knowing when to use each one is part of good decision-making.

The OODA loop was described for “thinking first” decisions. Key points here were understanding available information sources, integrating the information into a situational assessment so as to affect the meta-decision and decision processes, continually balancing the key trade-offs needed with the search for more information so that an appropriate decision is made on a timely basis, and following through with implementation and monitoring activities.

A process called RPD was described for “seeing first” (quick-response) decisions. The use of either the OODA loop or RPD was recommended for “doing first” decisions.

Near the end of the chapter, we provided a quick overview of the many types of decision aids that are available to decision makers. Some of the qualitative aids will be described in the remainder of the book. References were provided for the other types of aids.

Finally, the implementation of decisions was addressed.

In Chapter 5, we identify the hundreds of decisions that are required to successfully manage projects. The decisions we identify are presented as part of a decision structure that represents both the product system and the development system.